Abstract

Introduction:

Clinovations Government Solutions (CGS) was contracted in 2013 to conduct a mixed-methods evaluation of the District of Columbia (D.C.) Health Information Exchange (HIE) program as part of their Cooperative Agreement Grant funded by the Office of the National Coordinator in 2010. The evaluation was to focus on the progress of the HIE, how many providers and hospitals were participating in the program, and what benefits were being realized through the use of the HIE. During the course of the evaluation, the CGS team found that the use of the HIE to support public health reporting was one of its core elements.

Background:

The D.C. HIE is one of 56 HIE that were funded out of the Cooperative Agreement program. The HIE program was managed by the District of Columbia Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF), which also manages the District of Columbia Medicaid Program. The program was initially designed to accomplish the following: developing state-level directories and enabling technical services for HIE within and across states; ensuring an effective model for governance and accountability; coordinating an integrated approach with Medicaid and public health; and developing or updating privacy and security requirements for HIE within and across state borders. As the evaluation progressed, the CGS team discovered that the relationship between the DHCF and the District of Columbia Department of Health (DOH) had become a cornerstone of the D.C. HIE program.

Methods:

The CGS team used a mixed-methods approach for the evaluation, including a review of documents developed by the DHCF in its HIE program, including its original application. We also conducted 10 key informant interviews and moderated two small-group discussions using a semistructured protocol; and we developed a survey that measured the use, satisfaction, and future sustainability of the HIE for over 200 providers within the District of Columbia.

Findings:

While the evaluation focused on the D.C. HIE program in its entirety, the results indicated the value of utilizing the HIE for public health reporting to enhance the surveillance activities of the DOH. Specifically, the DHCF and DOH collaboration resulted in using the HIE to electronically capture and report immunization data; and in requiring electronic lab reporting and results as part of the Meaningful Use Requirement—which can assist in detecting HIV/AIDS and providing better care for the district’s high population of individuals with HIV/AIDS. Electronic lab reporting and electronic prescribing within the HIE can assist the DOH and providers in identifying specific diseases, such as tuberculosis and viral hepatitis, before they affect a significant part of the population.

Discussion:

Given the severe health disparities in the district, the ability of the D.C. HIE program to collect public health information on affected populations will be instrumental in better understanding and identifying methods of supporting these populations through improved surveillance and identification of the appropriate treatments. The D.C. HIE program is uniquely positioned to support these populations due to the partnership of DHCF with the D.C. DOH.

Conclusion and Next Steps:

The District of Columbia has made significant strides in expanding its public health infrastructure and activities. Three key areas of growth were identified that have the potential to transform the District of Columbia’s public health approach: establishing sufficient feedback loops, collection of environmental data, integration, and interoperability.

Keywords: health information exchange, public health, informatics

Introduction and Background

The State Health Information Exchange Cooperative Agreement Program, which was developed and released by the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC) in 2009, distributed over $564 million to states and territories to enable HIE within their jurisdictions. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) established the State HIE Cooperative Agreement Program as part of its larger goal to promote the adoption of health information technology (HIT) and health information exchange (HIE) capabilities in the United States—seen by the federal government as key to improving health care delivery.1 According to the funding opportunity announcement (FOA), the agreement was intended to facilitate the “development of statewide policy, governance, technical infrastructure and business practices needed to support the delivery of HIE services.”2 Some of the activities supporting this program include the following:

Developing state-level directories and enabling technical services for HIE within and across states;

Convening health care stakeholders to ensure trust of and support for a statewide approach to HIE;

Ensuring that an effective model for HIE governance and accountability is in place;

Coordinating an integrated approach with Medicaid and public health; and

Developing or updating privacy and security requirements for HIE within and across state borders.

In the District of Columbia, these activities were carried out with a unique focus on leveraging HIE functionality to improve public health infrastructure. The benefits of these improvements are twofold. Leveraging HIE functionality to improve public health reporting gives providers and hospitals the tools to more easily exchange health information and coordinate care for their patients, and ensures that they can achieve public health related Meaningful Use objectives. With this increased capacity for care providers to exchange health information and coordinate care, thousands of underserved patients in the District of Columbia can also see benefits in the form of improved quality of care and improved quality of life.

The District of Columbia (D.C.) HIE is the entity currently serving the District of Columbia. It is one of 56 state or state-designated HIEs in the United States and its territories that are tasked with improving care coordination and lowering costs through the use of HIT. It is staffed and managed by the D.C. Department of Health Care Finance (DHCF), which is also responsible for implementing provisions of several health-care related federal laws including the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, as well as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). In 2010, they were awarded a grant from ONC to plan and implement statewide HIE. As part of this program, the District of Columbia was expected to accomplish several goals, including developing state-level directories and enabling technical services for HIE within and across states; convening health care stakeholders to ensure trust of and support for a statewide approach to HIE; ensuring an effective model for governance and accountability; coordinating an integrated approach with Medicaid and public health; and developing or updating privacy and security requirements for HIE within and across state borders.3

On February 15, 2012 the District of Columbia mayor, Vincent Gray, established the D.C. HIE Policy Board to advise the mayor, the director of the DHCF, and other district agencies, regarding the implementation of secure, protected health information benefitting district stakeholders in accordance with the DHCF HIE Action Plan. The D.C. HIE Policy Board is an independent policy making committee under the direction of DHCF, and it focuses on developing policies essential to broad implementation of secure, protected HIE benefiting district stakeholders. The board is responsible for advising DHCF and the mayor on the overall strategic direction for D.C. HIE, as well as providing recommendations on its development and implementation. Working with the Statewide HIE HIT Coordinator and other strategic advisors, the board provides feedback on the implementation of technical and policy components that are critical to a successful HIE.

It was structured to provide multidisciplinary, multi-stakeholder representation and collaboration; to promote transparency, buy-in, and trust; and ensure coordination and alignment efforts across the District of Columbia. The board consists of 21 voluntary members, including 7 district government representatives appointed by the mayor.

Since the submission of the D.C. HIE’s initial Strategic Plan in 2011, the Policy Board, along with DHCF’s leadership, stake-holders, and consumers, have strengthened their commitment to providing a robust and interoperable network that facilitates the exchange of patient- and population-level information between hospitals, providers, and the District of Columbia government. To accomplish this, the District of Columbia developed a practical view of best practices from the experiences of other states with respect to governance, operations, and sustainability. As a result, major modifications were made to the D.C. HIE strategy, and the program emphasis shifted to focus on using the HIE for public health reporting, leveraging existing HIE technology to provide a connectivity infrastructure for enhancement in future phases, and establishing connections between health care entities. These modifications included the following.

Public Health Expansion

Along with the District of Columbia Department of Health (DOH), DHCF leveraged existing funding under the ONC grant to expand the current infrastructure to help providers and hospitals electronically submit information to public health agencies to achieve public-health related Meaningful Use objectives. The D.C. DOH intends on integrating the Orion Rhapsody platform into existing electronic health record (EHR) products or through a direct interface to facilitate the exchange of data and enhanced public-health reporting across cancer registries, syndromic surveillance, electronic lab reporting, and immunizations.

These changes were deliberated on and discussed with the Policy Board and were approved by ONC. Based on the current landscape of HIE in the district and the experiences of other state HIEs, the District of Columbia was working toward leveraging existing technical architecture and established HIE infrastructure to orchestrate connections across the state and region to achieve interoperability within and outside of the District of Columbia, while ensuring the use of existing and future resources to maintain operations in the future.

Utilizing the D.C. HIE for public health reporting was important in supporting providers and hospitals wishing to achieve Meaningful Use; however, establishing the HIE also built a foundation for the exchange of other health information, through services such as Direct Secure Messaging and the Hospital Connection program.

Direct Secure Messaging

The D.C. HIE is currently providing Direct Secure Messaging (Direct) to all providers in the district by issuing direct secure email addresses accessed through a secure web portal, and by providing Health Information Service Provider (HISP) services that will establish trust relationships with other HISPs in the region, including neighboring state HIEs and EHR vendor exchange hubs. This secure messaging infrastructure will be leveraged to provide additional technology services including encounter notifications, reporting services, and public health reporting capabilities.

Hospital Connection Program: Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patient (CRISP) Connection

DHCF used a portion of its grant funds to issue subgrants to hospitals located in the District of Columbia to connect to an existing state-designated HIE for the provision of advanced services. Six acute care hospitals within the District of Columbia chose the Chesapeake Regional Information System for our Patients (CRISP), Maryland’s state-designated HIE, to send patient information through Admissions, Discharge, and Transfer (ADT) feeds, which will in turn provide three main services for the D.C. HIE. These services include the following: provision of a query portal in which District of Columbia providers can perform a demographics-based search to view inpatient health information obtained from hospital ADT feeds; encounter notifications to providers in the district based on matching inpatient ADT messages and a subscriber list; as well as an encounter reporting service, which provides reports to hospitals on utilization trends across multiple independent facilities.

Methods

Clinovations Government Solutions (CGS) conducted a mixed-methods evaluation of the D.C. HIE program that focused on the adoption and use of HIE by providers and key stakeholders, the effectiveness of D.C. HIE functionality, and the manner in which the HIE supported public health initiatives. The evaluation focused on an 18-month period beginning in March 2012, as that allowed for the collection and reporting on data that aligned with the key success measures developed by ONC, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Success Measures of the State HIE Cooperative Agreement Program

| Success Factor | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Governance | Establishment of a governance structure and policies and procedures of the District of Columbia (D.C.) HIE |

| EHR Adoption | An increase in EHR adoption as a result of the D.C. HIE |

| Implementation | The progress of the D.C. HIE implementation and its use by physicians and other key stakeholders |

| Conformance | Conformance of the D.C. HIE to the Program Information Notices released by ONC over the duration of the program |

| Meaningful Use | The ability of the D.C. HIE to meet the criteria for State One of Meaningful Use for electronic prescribing, lab results delivery, and electronic care summary exchange via Direct Secure Messaging, and their level of preparedness for Meaningful Use Stage Two. |

As shown in Table 2, the evaluation study began with the development of a logic model through the examination of a number of documents from DHCF, including its initial application for the State HIE Cooperative Agreement Program; its original strategic and operational plan; monthly and quarterly reports filed to ONC; and drafts of strategic plans and agreements with CRISP and Orion Heath, the provider of the Direct HIE protocol.

Table 2.

Logic Model for the D.C. HIE Evaluation

| Development | Implementation | Operational |

|---|---|---|

|

D.C. HIE Program Starting Conditions:

Resources Provided by ONC

|

D.C. HIE Program (Proximal Outcomes)

Moving the HIE to Operational Phase

|

D.C. HIE Program (Distal Outcomes)

|

Key HIE planning inputs for the baseline and logic model included the initial governance model, identification of key stakeholders, collaboration with district and federal partners, the initial sustainability model, the type of technical infrastructure model, and additional characteristics of the D.C. HIE organization. Development inputs consisted of a requirements definition for the HIE, overall organizational readiness, the design of business plans, review of security protocols, review of district and federal privacy laws, usability of the HIE, HIE vendor selection, outreach, and education. Finally, operational inputs included the rate of lab test ordering over time, use of electronic prescribing services, integration of the HIE with providers, integration of the HIE into the clinical workflow, integration of the D.C. Medicaid program into the HIE, coordination of Medicare and federally funded, district-based programs into the HIE, and the execution of the operational plan to harmonize privacy and security requirements.

Source material, such as the original grant application and the initial strategic plan developed in 2011, was abstracted by CGS to identify data elements that aligned with the evaluation outcomes. Table 3 shows the domains used to categorize the data collected, the data points gathered from the material, and the data source. Information was classified according to its respective domain and then examined to identify common themes or key points.

Table 3.

Categorization of Data by Domains

| Domains | Data Points | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Information Required by ONC |

|

|

| Current Requirements for the D.C. HIE Program |

|

|

| Future Requirements for D.C. HIE Program |

|

|

Notes:

Capacity Builder is an HIE model developed by ONC that bolsters substate exchanges through financial and technical support, which is tied to performance goals.

An Orchestrator HIE model is a thin-layer, state-level network that connects with existing substate exchanges.

As part of the data collection process, an environmental scan was conducted in order to gain a better understanding of the District of Columbia population including racial and ethnic breakdown, poverty levels, Medicaid enrollment, and prevalence of chronic diseases.

CGS also conducted 10 key informant interviews with individuals identified by DHCF as having a significant role in the D.C. HIE program, as either a participant or a contributor. A semi structured interview protocol was designed that focused on areas such as the current perceptions of the D.C. HIE program, privacy and security concerns, the future direction of the D.C. HIE, barriers and obstacles to the success of the program, and strategies and ideas to move D.C. HIE forward. Additionally, two small-group discussions were conducted with individuals who were part of the D.C. HIE Policy Board, by using another semistructured protocol similar to the one used for the key informant interviews. The purpose was to gather information about the history of the D.C. HIE and to understand the progression of the program over the past 18 months.

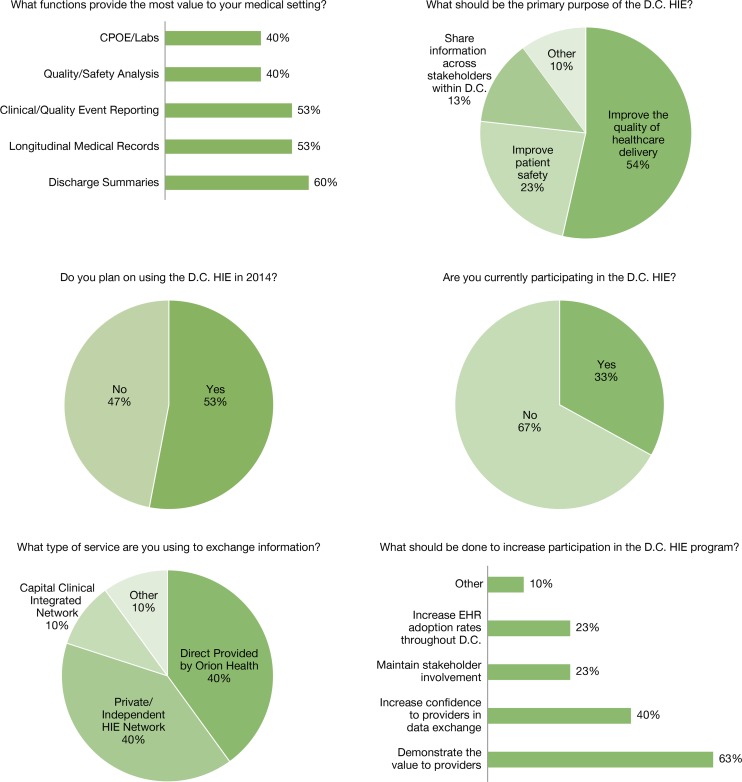

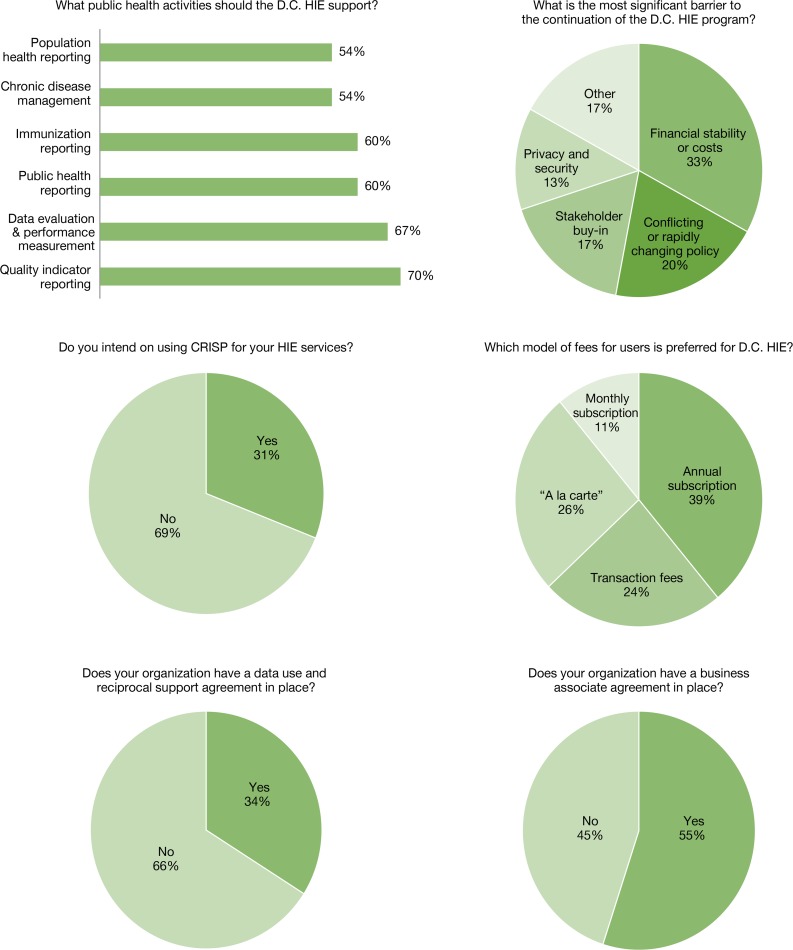

Finally, a 12-question cross-sectional survey for key stakeholders was developed and released on October 1, 2013. This survey was targeted to over 148 individuals and stakeholders identified by DHCF as either being participants in D.C. HIE or being interested in becoming involved in assessing stakeholder representation, enrollment in and use of specific platforms (such as Direct and CRISP), financing models, and the progress of D.C. HIE development. The survey questions focused on areas such as the current usage of the D.C. HIE, what functions they found most useful, what they believe the primary purpose of the D.C. HIE should be, their privacy and security practices, and what they believe are the primary barriers to the success of the D.C. HIE program. The survey was created in Google Docs and sent to 148 potential respondents provided by DHCF on October 15, 2013; 30 responses were received back (a 20 percent response rate), and the survey was closed November 4, 2013.

Results

The evaluation began July 1, 2013 and concluded January 6, 2014 as CGS was able to identify and assess the success factors to provide feedback to both DHCF and ONC. As shown in Figure 1, the survey results provided an overview of the current and future activities of the D.C. HIE, in which additional exploratory analysis was done through the environmental scan, interviews, and small group discussions.

Figure 1.

Results of D.C. HIE Evaluation Survey (n =30)

The remainder of this paper highlights how D.C. HIE focused on improving public health in the District of Columbia through collaboration between DHCF and D.C. DOH, encouraging district providers to adopt EHRs, and identifying public health surveillance as a primary value driver for the D.C. HIE program.

Collaboration between Medicaid and Public Health

Through both stakeholder interviews and the small-group discussions, it was discovered that while the D.C. HIE has some weaknesses in its governance structure, namely, that the Policy Board does not always evolve and change as the HIE program progresses, the model is sound overall. The board maintains openness and transparency by holding public meetings with minutes from past meetings and with dates and locations of future meetings posted on its website. Additionally, it ensures that the program’s policies and procedures and applicable federal and state laws are adhered to.

Although it has encountered challenges in maintaining adequate stakeholder representation that aligns with new strategic directions (with a marked gap in patient- and patient-advocate representation), the board and DHCF made concerted efforts to work with a variety of stakeholders and interest groups throughout the implementation of the D.C. HIE, including additional government care-coordination programs, private payers, Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), and the D.C. DOH. The collaboration between DHCF and the D.C. DOH was of particular significance, not only because it was a major driver in improving the district’s public-health reporting infrastructure, but also because this type of collaboration between a state’s public-health and Medicaid agencies is quite unique.

The role of D.C. HIE and its governance model have evolved considerably since its inception. In 2011, the original strategic planning of the program involved supporting and expanding existing HIE services through financial- and policy-based support in a Capacity Builder role.ii With the advent of a new HIT Coordinator and program staff, the board shifted strategies to providing comprehensive services directly from the District of Columbia through contracting an HIE technical provider. Under this approach, D.C. HIE would serve in a public utility role, in which HIE services would be provided directly to end users and substate exchanges. Under motivation from ONC, D.C. HIE modified its strategy in 2013 to fund a selection of key HIE services—including upgrading and expanding public health reporting capabilities, connection of hospitals and the District of Columbia providers to neighboring state HIEs, and continuing to provide Direct Secure Messaging addresses and infrastructure directly to all District of Columbia providers and relevant stakeholders. Each of these services functions under a disparate governance entity with established policies, procedures, and governance models.

In efforts to coordinate the governance of these entities, the D.C. HIE includes the D.C. DOH on its Policy Board, invites representatives from other HIE organizations (e.g., CRISP, CCIN) to participate in its board meetings, and is currently exploring formalized methods of collaborative governance among these entities. D.C. HIE serves as a hybrid of an Orchestratoriii and Capacity Builder to use its Direct Secure Messaging infrastructure to connect existing exchanges in the region—including district government entities, neighboring state exchanges, publicly funded care coordination programs, and private exchanges.

Electronic Health Record (EHR) Adoption and Public Health Reporting

Through reviewing both the initial grant application and supporting materials, it was discovered that the immediate goal of the D.C. HIE was to work closely with the District of Columbia Regional Extension Center (REC) to ensure that all providers in the district adopt EHRs and are positioned to meet their public health Meaningful Use requirements within the required timelines from 2012 to 2017. The District of Columbia Primary Care Association (DCPCA), which serves as the REC, reports that about 1,000 of the city’s primary care providers are projected to actively participate in the D.C. REC and to commit to achieving Meaningful Use within the required time frames. This represents a rate of about 70 percent of the city’s estimated 1,400 licensed primary care providers. Approximately 112 providers are currently using the D.C. HIE to transmit public health information, such as immunization and syndromic surveillance data, to the D.C. DOH, and to transmit other health information to other providers and hospitals through Direct Secure Messaging.

The D.C. DOH collected data from a variety of sources including the D.C. REC, D.C. HIE, ONC Dashboard, and the DOH Health Regulation and Licensing Administration to assess provider adoption of electronic medical records (EMRs) and EHRs and their participation in the D.C. HIE. Results of the data collection were reviewed by the CGS team and are summarized in Table 4 (as of October 30, 2013).

Table 4.

Providers Using Certified Electronic Health Record (EHR) Technology

| Registered for the REC | Using Certified EHR Technology | Achieved Meaningful Use | Enabled by Direct (D.C. HIE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providers | 924 | 808 (88%) | 585 (63%) | 60 |

| Data Source | D.C. REC | D.C. REC | D.C. REC | D.C. HIE |

Public Health as a Value Driver

The results of the informant interviews and small-group discussions indicate that—even with the implementation of the D.C. HIE—there is still a lack of understanding among stake-holders and providers regarding its value. While a vast amount of literature underscores the value of HIE in broad terms, it has been difficult to specifically identify value propositions that align with the patient- and provider populations within the District of Columbia.

It was through this data that the value of utilizing the HIE for public health reporting in order to enhance the surveillance activities of the D.C. DOH was discovered. Public health surveillance through HIE in the district has the potential of benefiting a population of more than five million who live in the Washington Metropolitan Area, including surrounding counties in Maryland and Virginia. The public health issues affecting this population are significant, with a high percentage living in poverty, high volumes of Medicaid enrollment, and a large homeless population. The district has the third-highest poverty rate in the nation—with about 18.2 percent of residents living at or below the poverty line, and approximately 15 percent of families living below the poverty line. Of the district’s eight wards, Wards 7 and 8 contain 10 times the number of residents living in poverty than those in Ward 3. Comparatively, the poverty rate for the United States as a whole is 14.3 percent, while in nearby Maryland and Virginia the poverty rates are 9.0 percent and 10.7 percent, respectively. In alignment with the district’s high poverty rates, Medicaid enrollment in the district in 2010 was 35 percent of the total population, which was 14 percent higher than the national average.4 A significant portion of the district’s population also faces homelessness. In 2011, the District of Columbia had a rate of 108 homeless per 10,000 individuals, while the national average was 21 per 10,000 individuals.5

Additionally, persons of specific racial and ethnic minority populations living in the District of Columbia often experience severe health disparities and may be disproportionately affected by chronic diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus infection/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), sexually transmitted infections (STIs), tuberculosis (TB), and hepatitis. For example, the incidence rate of cancer for white residents in the District of Columbia was 313.6 per 100,000, but for black residents was 481.8 per 100,000, compared to 473.1 per 100,000 in the United States overall. In 2010, diabetes rates were highest in Wards 8, 5, and 7, which also had the highest percentages of black residents (93.6 percent, 79.4 percent, and 95.3 percent, respectively). The District of Columbia also continued to report high rates of STIs relative to the overall United States population in 2010—with the highest aggregate rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea in Wards 7 and 8, while the lowest rates were in Ward 3, where 77.2 percent of the population was white.6,7

The evaluation results indicated that one of the primary value drivers for participation and continued sustainability of the HIE was utilization of the HIE to exchange public health data and to increase public health reporting. In doing so, the HIE would provide valuable information to assist in surveillance activities, primarily around the health issues that disproportionately affect District of Columbia residents. Utilizing the HIE for this purpose can also provide insight into the types of treatments and strategies being used to provide care and to determine their overall effectiveness. As shown through the data collected from the survey and the key informant interviews, the best way to accomplish that goal is to leverage the HIE to assist health care providers in meeting Meaningful Use objectives (i.e., submission of electronic immunization data, submission of electronic syndromic surveillance data, summary of care record transmission for transitions of care).

More specifically, many informants and key stakeholders within the small-group discussions described enabling primary care providers through the HIE to adopt and implement electronic prescribing capabilities in conjunction with the D.C. REC’s support services; increasing adoption of receiving laboratory results electronically from clinical laboratories; and enabling the transmission and receipt of clinical summary data in a consistent electronic document format to provide critical and necessary information to diagnose and understand a patient—as well as to provide valuable information on the District of Columbia population. In doing so, the D.C. HIE will provide immediate and needed value, which will encourage greater participation and a willingness to maintain the HIE through the use of alternate funding sources apart from federal grant funds.

Based on data from a mandatory quarterly report that DHCF had to provide to ONC at the end of the first quarter of 2013, 99.23 percent of all pharmacies were capable of e-prescribing, three laboratories (one hospital, two independent) were developing use cases with DHCF for electronic lab reporting, and the use of Direct would serve as the transport foundation for enabling reliable and secure exchange of patient care summaries using the Continuity of Care format.

Although the data indicated that a majority of providers were not currently using the D.C. HIE, those that were actively using the exchange were leveraging the Direct Secure Messaging system or an independent provider of HIE services, such as the Capital Clinical Integrated Network (CCIN), specifically for public health reporting. DHCF is currently working with the D.C. DOH to expand the public health capabilities of the HIE beyond those required for Meaningful Use. In the areas of immunization reporting and surveillance reporting for syndromic events, DOH has the capacity to receive electronically 100 percent of immunization, electronic lab reporting, and surveillance data. Because DOH has been working diligently with providers to transition them from paper reports to full electronic reporting, there has been a dramatic increase in electronically reported immunizations since 2012, with only 48 providers submitting immunization data in a nonelectronic format.

This has tremendous potential for the district as several studies have indicated that automated immunization reporting through an HIE can accelerate the collection of vaccine data and provide a more robust and accurate assessment of the at-risk populations that are not receiving their appropriate vaccinations.8 Tracking immunizations poses a challenge to public health agencies—especially in areas such as the District of Columbia—that have a large population of underserved individuals, low-income patients, and children that may receive vaccines through multiple providers.9 A study conducted by the New York Citywide Immunization Registry in 2012 indicated that using automated reporting through the combination of EHR and HIE increased the submission of new vaccine records by 18 percent and historical records of vaccines increased by 98 percent.10 Furthermore, the use of an HIE can also bridge the gaps between multiple providers, as an exchange that leverages electronic prescribing functionality can collect and transmit immunization notifications from clinics to a patient’s primary care provider.

Additionally, the increase in public health reporting through the D.C. HIE may also improve access and the quality of HIV/AIDS care. Within the district, individuals living with HIV/AIDS may be mobile and may seek care from multiple providers, which makes the assessment of the disease and the accessing of a patient’s care history difficult.11 Through the use of an HIE, providers and public health officials can facilitate early detection of HIV infection and reduce the amount of time for an infected individual to enter care, it can improve the management of patient health information, and it can improve the engagement of people living with HIV/AIDS in the management of their own care.12 The Network of Care Initiative, created by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) as part of their Special Projects of National Significance Program (SPNS), developed an electronic bridge between its participants and local agencies using clinical management software. The primary function of this application was a bidirectional interface that would capture and disseminate laboratory results and medication orders from their patients’ EHRs. Doctors were able to access patients’ laboratory results in real time. And they were able to discuss critical information more easily with patients, which results in improvement in patients’ CD4 counts and viral load as well as facilitating better treatment planning.13

The evaluation results also demonstrate the utility of electronic laboratory results in providing mandatory information regarding specific diseases. The District of Columbia requires mandatory reporting on diseases such as tuberculosis and viral hepatitis. Facilitating the electronic exchange of laboratory results to health departments has been shown to improve the timeliness and completeness of reporting.14 Additionally, it may also increase the efficiency and quality of public health surveillance, particularly for high volume diseases.15 The HIE can also assist physicians in the reporting of these diseases because of their use of specific diagnosis, procedure, or medication codes that would identify cases that may have gone unreported.16

Discussion

Given the severe health disparities present in the district, the ability of the D.C. HIE to collect public health information on affected populations will be instrumental in better understanding them and in identifying methods of supporting them through better surveillance and an ability to identify the appropriate treatments. The D.C. HIE program is uniquely positioned to support these populations due to the partnership of DHCF with the D.C. DOH. Together, these organizations have thus far leveraged existing funding under the ONC grant to expand the infrastructure to help providers and hospitals achieve Meaningful Use public health objectives. The DOH has prioritized support of providers in achieving Stages 1 and 2 of Meaningful Use including developing the ability for providers to send—and for the DOH to receive—immunization data, syndromic surveillance data, lab results, and cancer lab results. While the D.C. HIE program was created within the framework of the ONC Cooperative Agreement Program, the conjoined efforts of both agencies to support hospital and providers with public health reporting have moved the District of Columbia forward in realizing the benefits of HIE.

Significant investment in the district’s public health infrastructure will also lead to the following three major areas of enhancement of health and resources in the district.

Quality of Care

A centralized reporting system for various metrics with interoperable data will allow for increased care coordination facilitated by the District of Columbia government as well as increased accountability for different care settings. The district will be able to understand whether certain settings are underperforming and can focus efforts on those settings. Collecting metrics on immunization data allows the district to ensure that patients are appropriately protected throughout all parts of the city, regardless of socioeconomic status.

Health System Transformation

This significant investment will allow for better public health surveillance, with more focused activities relating to intervention, prevention, and wellness. Enhanced public health reporting will also allow for a better understanding of the current state of public health in the district, better forecasting of disease rates, and more efficient allocation of funding.

Optimization

A standardized form of data will prove invaluable when analyzing data across the district’s wards and populations. Standardized data capture will result in an increased amount of objective data on which to base analysis—providing the opportunity for better allocation of resources, more useful data sharing among the district’s various health-related departments and programs (e.g., Medicaid), and better access to information.

In addition to activities related to public-health reporting infrastructure, DHCF has made a concerted effort to leverage HIE infrastructure to support other initiatives. For example, D.C. HIE is coordinating with the District of Columbia Medicaid Health Homes project, established through grant funding from the ACA, to use health HIT to support individuals with chronic conditions. These efforts could lead to enhanced sharing of mental health information, aggregation of data for program evaluation, analysis of claims data to inform needs assessment, and coordination and integration of health beneficiary organizations, among others. The more recent establishment of the District of Columbia’s Health Benefits Exchange (HBX) in accordance with the ACA has also created an opportunity for D.C. HIE to identify points of synergy and to minimize the duplication of efforts between HIE and HBX in the district, as well as to analyze best practices from the experiences of other states. This will serve as a foundation for creating a community of care within the District of Columbia in which providers, hospitals, payers, patients, and government entities work collectively in the provision and monitoring of care by providing timely and needed information about the health status both of individuals and of a population.

Furthermore, by expanding the D.C. HIE to encompass public health reporting beyond those measures established by Meaningful Use, and by leveraging it to support initiatives established through health reform, the D.C. HIE creates more opportunity for its participants. It will provide more value for stakeholders within the District of Columbia medical community, as the ability to get needed information specific to the district’s patient population may be invaluable. As a result, the D.C. HIE program can examine sustainability models that extend beyond the grant period and that rely on participants contributing dollars on a subscription or transaction basis. If the true value of the D.C. HIE is realized, there may be more inclination to participate beyond the Cooperative Agreement period.

Conclusion

Throughout the course of the evaluation, a number of recurrent themes in the findings provided insight into the current state of D.C. HIE and its capacity to facilitate public health reporting and the steps needed for it to maintain progress and expand functionality into 2014 and beyond.

A Defined Value Proposition

A value proposition must be defined for the D.C. HIE that is specific to the District of Columbia area and that providers and other stakeholders can relate to. It must consider the diverse population within the district, as well as the close relationship between DHCF and DOH in their combined goal to improve public health. This will increase participation in the D.C. HIE in 2014 and beyond, and will assist in its sustainability. Meaningful Use objectives have emphasized electronic prescribing, and electronic lab reporting and patient care summaries, while the ability of the D.C. HIE to collect and use data for public health in ways that achieve Meaningful Use objectives and, potentially, expand beyond them could provide significant value to providers. As the evaluation results show, the most significant value can be realized through increased public health surveillance and reporting by the D.C. HIE.

Increased Participation in the Health Information Exchange (HIE)

As demonstrated in the survey results, increasing participation in the D.C. HIE is critical to the future success of the program on many levels. Increased participation will benefit patients by allowing for better care coordination across providers and care settings—providing open lines of communication for providers and allowing them to access patient data more quickly and efficiently; it will generate revenue for the D.C. HIE program to sustain itself after federal funding is depleted, and it will allow for the collection of important data that can be used to benefit the larger community through population health management initiatives. Greater participation occurs when value is realized—and a community utilizing data from the D.C. HIE to monitor the health of its citizens becomes a high value proposition.

A Sustainable, Value-Driven Model

The D.C. HIE program must fit district priorities and stakeholder values while remaining sustainable—with a corresponding governance model that will best ensure that activities are successful. Key factors in such an approach will be to develop a community that uses the information to support elements of health care reform, such as new care delivery models like Medicaid health homes; that provides value to the population by offering data that provides more robust and comprehensive surveillance and reporting activities; and that ensures that value is communicated to and utilized by providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the leadership and support of Cleveland Woodson and Michael Tietjen of the D.C. Department of Health Care Finance, who served as the Project Directors for the D.C. HIE Evaluation. Their guidance and knowledge of the D.C. HIE program was invaluable in the design and execution of the evaluation. We would also like to the Arturo Weldon from the D.C. Department of Health for his efforts in providing information on the connection between the D.C. HIE program and the Department of Health. We would also like to thank both the D.C. HIE Advisory Board for their advice and support and Rachel Abbey from the Office of the National Coordinator for her guidance and review of the final evaluation report.

References

- 1.Office of the National Coordinator American Reinvestment and Recovery Act off 209 – Title XIII – Health Information Technology, subtitle B – Incentives for the Use of Health Information Technology, Section 3013 – State Grants to Promote Health Information Technology, State Health Information Exchange Cooperative Agreement Program, Funding Opportunity Announcement. Department of Health and Human Services. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 2.NORC at the University of Chicago Evaluation of the State Health Information Exchange Cooperative Agreement Program: Early Findings From a Review of Twenty-Seven States. 2012 Jan; [Google Scholar]

- 3.NORC at the University of Chicago The evolution of the state health information Exchange cooperative agreement program: State plans to enable robust HIE. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation . Medicaid Enrollment as a Percent of Total Population, 2010. Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Witte P. The State of Homelessness in America 2012. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chandra A, Blanchard J, Ruder T. District of Columbia Community Health Needs Assessment [Internet] RAND Health. 2014. [3 March 2014]. Available from: http://assets.thehcn.net/content/sites/washingtondc/CHNA_2013_FINAL_052913.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.ANNUAL EPIDEMIOLOGY & SURVEILLANCE REPORT [Internet] Washington, DC: Department of Health; 2011. [6 April 2014]. Available from: http://doh.dc.gov/sites/default/files/dc/sites/doh/publication/attachments/2012AESRFINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bresnick J. Using EHR, HIE to share vaccine data improves public health. EHR Intelligence [Internet] 2013. [10 April 2014];. Available from: http://ehrintelligence.com.

- 9.Grannis S, Dixon B, Brand B. LEVERAGING IMMUNIZATION DATA IN THE E-HEALTH ERA. Public Health Informatics Institute and the Regenstreif Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh B. NY HIE offers immunization reporting. Clinical Innovation + Technology [Internet] 2013. [9 April 2014];. Available from: http://www.clinical-innovation.com.

- 11.Radcliffe J, Doty N, Hawkins L. Stigma and sexual health risk in HIV-positive African American young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:493–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unertl K, Johnson K, Lorenzi N. Health information exchange technology on the front lines of healthcare: workflow factors and patterns of use. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012;19(3):392–400. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Health Resources and Services Administration . Leveraging Health Information Technology to Improve Access to and Quality of HIV/AIDS Care. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shapiro J. Evaluating public health uses of health information exchange. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2007;40(6):46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards J, LaVenture M, Snow L, Hanrahan L, Ross D. Planning for Public/Private Health Data Exchange: A National and State-Based Perspectice. American Medical Informatics Association; 2006. AMIA Annual Symposium. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barthell E, Cordell W, Moorhead J, Handler J, Feied C, et al. The Frontlines of Medicine Project: a proposal for the standardized communication of emergency department data for public health uses including syndromic surveillance for biological and chemical terrorism. Annals of emergency medicine. 2002;39(4):422–429. doi: 10.1067/mem.2002.123127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamond C, Mostashari F, Shirky C. Collecting and sharing data for population health: a new paradigm. Health affairs. 2009;28(2):454–466. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lumpkin J, Richards M. Transforming the public health information infrastructure. Health Affairs. 2002;21(6):45–56. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.6.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitsch L, Brooks R, Menachemi N, Libbey P. Public health at center stage: new roles, old props. Health Affairs. 2006;25(4):911–922. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.4.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larsson S, Lawyer P, Garellick G, Lindahl B, Lundstrom M. Use of 13 disease registries in 5 countries demonstrates the potential to use outcome data to improve health care’s value. Health Affairs. 2012;31(1):220–227. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]