Abstract

Objective

To estimate the proportion of participants in clinical trials who understand different components of informed consent.

Methods

Relevant studies were identified by a systematic review of PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar and by manually reviewing reference lists for publications up to October 2013. A meta-analysis of study results was performed using a random-effects model to take account of heterogeneity.

Findings

The analysis included 103 studies evaluating 135 cohorts of participants. The pooled proportion of participants who understood components of informed consent was 75.8% for freedom to withdraw at any time, 74.7% for the nature of study, 74.7% for the voluntary nature of participation, 74.0% for potential benefits, 69.6% for the study’s purpose, 67.0% for potential risks and side-effects, 66.2% for confidentiality, 64.1% for the availability of alternative treatment if withdrawn, 62.9% for knowing that treatments were being compared, 53.3% for placebo and 52.1% for randomization. Most participants, 62.4%, had no therapeutic misconceptions and 54.9% could name at least one risk. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses identified covariates, such as age, educational level, critical illness, the study phase and location, that significantly affected understanding and indicated that the proportion of participants who understood informed consent had not increased over 30 years.

Conclusion

The proportion of participants in clinical trials who understood different components of informed consent varied from 52.1% to 75.8%. Investigators could do more to help participants achieve a complete understanding.

Résumé

Objectif

Estimer la proportion des participants à des essais cliniques qui comprennent les différents composants du consentement éclairé.

Méthodes

Les études pertinentes ont été identifiées par une revue systématique de PubMed, Scopus et Google Scholar et par l'examen manuel des listes des références des publications allant jusqu'à octobre 2013. Une méta-analyse des résultats de l'étude a été réalisée à l'aide du modèle à effets aléatoires pour tenir compte de l'hétérogénéité.

Résultats

L'analyse a inclus 103 études évaluant 135 cohortes de participants. La proportion regroupée des participants qui ont compris les composants du consentement éclairé était de 75,8% pour la liberté de se retirer à tout moment, de 74,7% pour la nature de l'étude, de 74,7% pour la nature volontaire de la participation, de 74,0% pour les bénéfices potentiels, de 69,6% pour l'objectif de l'étude, de 67,0% pour les risques et effets indésirables potentiels, de 66,2% pour la confidentialité, de 64,1% pour la disponibilité d'un traitement alternatif en cas de retrait de l'étude, de 62,9% pour la connaissance des traitements évalués, de 53,3% pour le placebo et de 52,1% pour la randomisation. La plupart des participants (62,4%) n'avaient pas d'idées fausses sur le traitement, et 54,9% d'entre eux pouvaient citer au moins un risque. Les analyses de sous-groupe et de métarégression ont identifié des covariables, telles que l'âge, le niveau d'éducation, la maladie grave, la phase et le site de l'étude, qui affectaient significativement la compréhension et indiquaient que la proportion des participants ayant compris le consentement éclairé n'avait pas augmenté sur une période de 30 ans.

Conclusion

La proportion des participants à des essais cliniques, qui ont compris les différents composants du consentement éclairé, variait de 52,1% à 75,8%. Les investigateurs pourraient en faire davantage pour aider les participants à parvenir à la compréhension complète.

Resumen

Objetivo

Estimar la proporción de participantes de ensayos clínicos que comprende los distintos componentes del consentimiento informado.

Métodos

Se identificaron los estudios pertinentes mediante una revisión sistemática de PubMed, Scopus y Google Scholar y el examen manual de listas de referencia a fin de hallar publicaciones anteriores a octubre de 2013. Se realizó un metanálisis de los resultados del estudio mediante un modelo de efectos aleatorios para tener en cuenta la heterogeneidad.

Resultados

El análisis incluyó 103 estudios que evaluaron 135 cohortes de participantes. La proporción combinada de participantes que entendía los componentes del consentimiento informado fue del 75,8 % para la libertad de retirarse en cualquier momento, 74,7 % para la naturaleza del estudio, 74,7 % para el carácter voluntario de la participación, 74,0 % para los beneficios potenciales, 69,6 % para el propósito del estudio, 67,0 % para los riesgos y efectos secundarios potenciales, 66,2 % para la confidencialidad, 64,1 % para la disponibilidad de tratamiento alternativo si el paciente se retira, 62,9 % para saber que se comparaban tratamientos, 53,3 % para el placebo y 52,1 % para la aleatorización. La mayoría de los participantes, el 62,4 %, no tenía una idea equivocada sobre la terapia y el 54,9 % no fue capaz de nombrar al menos un riesgo. Los análisis de subgrupos y la metarregresión identificaron covariables, como edad, nivel educativo, enfermedad crítica, fase de estudio y ubicación, que influían considerablemente en la comprensión y señalaron que la proporción de participantes que entendía el consentimiento informado no había aumentado en 30 años.

Conclusión

La proporción de participantes de ensayos clínicos que entendía los diferentes componentes del consentimiento informado varió del 52,1 % al 75,8 %. Los investigadores podrían realizar esfuerzos mayores para ayudar a los pacientes a lograr una comprensión total.

ملخص

الغرض

تقدير نسبة المشاركين في التجارب السريرية الذين يفهمون العناصر المختلفة للموافقة المستنيرة.

الطريقة

تم تحديد الدراسات ذات الصلة عن طريق استعراض منهجي لقواعد بيانات PubMed وScopus وGoogle Scholar وعن طريق استعراض يدوي لقوائم المراجع الخاصة بالمنشورات حتى تشرين الأول/أكتوبر 2013. وتم إجراء تحليل تال لنتائج الدراسة باستخدام نموذج التأثيرات العشوائية لوضع التغايرية في الحسبان.

النتائج

اشتمل التحليل على 103 دراسة تقوم بتقييم 135 مجموعة من المشاركين. وكانت النسبة المجمعة للمشاركين الذين فهموا عناصر الموافقة المستنيرة 75.8 % بالنسبة لحرية الانسحاب في أي وقت و74.7 % بالنسبة لطبيعة الدراسة و74.7 % بالنسبة لطبيعة المشاركة الطوعية و74.0 % بالنسبة للفوائد المحتملة و69.6 % بالنسبة لغرض الدراسة و67.0 % بالنسبة للمخاطر والآثار الجانبية المحتملة و66.2 % بالنسبة لسرية المعلومات و64.1 % بالنسبة لإتاحة العلاج البديل في حالة الانسحاب من التجربة السريرية و62.9 % بالنسبة لمعرفة إجراء مقارنات بين العلاجات و53.3 % بالنسبة للدواء الوهمي و52.1 % بالنسبة للتوزيع العشوائي. ولم يكن لدى معظم المشاركين، 62.4 %، مفاهيم علاجية خاطئة واستطاع 54.9 % تحديد خطر واحد على الأقل. وحددت تحليلات الفئات الفرعية وتحليلات الارتداد التالي المتغيرات المصاحبة، مثل السن والمستوى التعليمي والاعتلالات الحرجة ومرحلة الدراسة وموقعها، والتي أثرت بشكل كبير على الفهم وأشارت إلى أن نسبة المشاركين الذين فهموا الموافقة المستنيرة لم تشهد زيادة على مدار 30 سنة.

الاستنتاج

تراوحت نسبة المشاركين في التجارب السريرية الذين فهموا العناصر المختلفة للموافقة المستنيرة من 52.1 % إلى 75.8 %. ويستطيع الخبراء تقديم المزيد لمساعدة المشاركين في تحقيق الفهم الكامل.

摘要

目的

估算临床试验中参与者理解知情同意不同组成部分的比例。

方法

系统回顾PubMed、Scopus和Google Scholar来识别相关研究。使用随机影响模型执行研究结果荟萃分析,以便将异质性考虑在内。

结果

分析包括评估135组参与者的103项研究。参与者理解知情同意组成部分的混合比例为:75.8%理解随时退出的自由,74.7%理解研究的性质,74.7%理解参与的自愿性质,74.0%理解潜在收益,69.6%理解研究目的,67.0%理解潜在的风险和副作用,66.2%理解保密性,64.1%理解退出情况下替代治疗的提供,62.9%知道治疗正在接受比较,53.3%理解安慰剂,52.1%理解随机化。大多数参与者(62.4%)没有治疗误区,54.9%能够说出至少一个风险。子群和meta回归分析识别出年龄、教育水平、重要疾病、研究分期和位置等对理解产生显著影响的协变量,并指明30多年来参与者理解知情同意的比例并没有增加。

结论

临床试验参与者理解知情同意各个组成的比例为52.1%到75.8%不等。研究者可以做更多的工作来帮助参与者完全理解各个组成部分。

Резюме

Цель

Определить долю участников клинических исследований, которые понимают различные детали информированного согласия.

Методы

Соответствующие исследования были выявлены посредством систематического обзора PubMed, Scopus и Google Scholar, а также путем просмотра вручную библиографических списков публикаций, изданных до октября 2013 г. Мета-анализ результатов исследований проводился с помощью модели со случайными эффектами для учета разнородности.

Результаты

Анализ включал 103 исследования с оценкой 135 групп участников. Общие доли участников, которые понимали следующие компоненты информированного согласия, составляли: 75,8% — о праве прекратить участие в исследовании в любое время, 74,7% — о природе исследования, 74,7% — о добровольном участии, 74,0% — о потенциальной пользе, 69,6 — о целях исследования, 67,0% — о потенциальных рисках и нежелательных явлениях, 66,2% — о конфиденциальности, 64,1% — о наличии альтернативного лечения при выходе из исследования, 62,9% — о знании сравнения терапий, 53,3% — о плацебо и 52,1% — о рандомизации. Большинство участников, а именно 62,4%, имели правильное представление о терапии и 54,9% могли назвать по меньшей мере один риск. С помощью анализа данных в подгруппах и мета-регрессионного анализа были определены независимые переменные, такие как возраст, уровень образования, критическое заболевание, место проведения и фаза исследования, которые оказывали значительное влияние на понимание и указывали на то, что доля участников, понимающих информированное согласие, не увеличилась за 30 лет.

Вывод

Доля участников клинических исследований, которые понимали различные компоненты информированного согласия, варьировалась в диапазоне от 52,1% до 75,8%. Исследователи могли бы предпринять дополнительные меры, чтобы участники исследований в более полной мере поняли суть информированного согласия.

Introduction

Informed consent has its roots in the 1947 Nuremberg Code and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and is now a guiding principle for conduct in medical research.1,2 Within its ethical and legal foundations,3 informed consent has two specific goals in clinical research: (i) to respect and promote a participant’s autonomy; and (ii) to protect participants from harm.4,5 Obtaining written informed consent from participants before enrolment in a study is an internationally accepted standard.6–10

Five concepts must be considered in establishing informed consent: voluntariness, capacity, disclosure, understanding and decision.11,12 Voluntariness means that an individual’s decision to participate is made without coercion or persuasion. Capacity relates to an individual’s ability to make decisions that stems from his or her ability to understand the information provided. Disclosure involves giving research participants all relevant information about the research, including its nature, purpose, risks and potential benefits as well as the alternatives available.13 Understanding implies that research participants are able to comprehend the information provided and appreciate its relevance to their personal situations. Decision is that made to participate, or not.11,12

The quality of informed consent in clinical research is determined by the extent to which participants understand the process of informed consent.14 Understanding plays a pivotal role in clinical research because it directly affects how ethical principles are applied in practice.15–17 Although the literature on informed consent began to accumulate in the 1980s, little is known about how patients’ understanding has evolved as no meta-analysis has been previously performed. A systematic review considering literature up to 2006 found that only around 50% of participants understood all components of informed consent in surgical and clinical trials.18 Another systemic review, which included data up to 2010, compared only the quality of informed consent in developing and developed countries.19 The objective of this study was, therefore, to investigate the quality of informed consent in clinical trials in recent decades by performing a systematic review and meta-analysis of the data available.

Methods

We conducted a literature search of PubMed and Scopus using the following terms: “informed consent[mh] AND (comprehension[mh] OR decision making[mh] OR knowledge[mh] OR perception[mh] OR communication[mh] OR understanding) AND (randomized controlled trials as topic[mh] OR clinical trial as topic[mh])”. In addition, in a simple search of Scopus, we used: “allintitle: understanding OR comprehension OR knowledge OR decision OR perception OR communication “informed consent”.” In Google Scholar, we used the keywords “informed consent” as the exact phrase and “understanding, comprehension, knowledge, decision, perception, communication” with the option with at least one of the words and selected “where my words occur in the title of the article”. The search strategy was developed as previously described.20 The searches covered all data entered up to October 2013. In addition, we analysed the reference lists of relevant articles. All studies identified were reviewed independently for eligibility by two of five authors and conflicts were resolved by seeking a consensus with other authors.

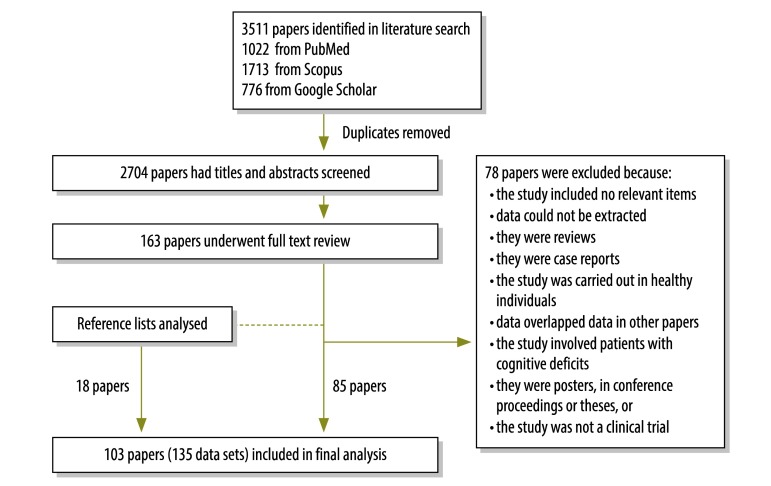

A study was eligible for inclusion if it assessed the participant’s or the participant’s guardian’s understanding of informed consent1,2 and at least one of the following components of the informed consent process:8,21 therapeutic misconception (i.e. lack of awareness of the uncertainty of success); ability to name at least one risk; knowing that treatments were being compared; or understanding of: (i) the nature of the study (i.e. awareness of participating in research); (ii) the purpose of the study; (iii) the risks and side-effects; (iv) the direct benefits; (v) placebo; (vi) randomization; (vii) the voluntary nature of participation; (viii) freedom to withdraw from the study at any time; (ix) the availability of alternative treatment if withdrawn from a trial; or (x) confidentiality (i.e. personal information will not be revealed). There was no restriction by language, age (i.e. children or adults) or study design. French and Japanese articles were translated into English by authors with a good command of these languages. We excluded articles on studies that: (i) compared or evaluated methods of informed consent; (ii) used an intervention to improve participants’ knowledge of informed consent; (iii) involved animals or included only healthy volunteers (e.g. simulated studies); (iv) involved patients with cognitive deficits; (v) were published as posters, in conference proceedings or as a thesis; or (vi) were not clinical trials. Our study protocol was registered with the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with the identifier CRD42013005526. The study selection process, which was carried out in accordance with MOOSE guidelines for meta-analyses and systematic reviews of observational studies, is shown in Fig. 1.22

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for the selection of studies on participants’ understanding of informed consent in clinical trials

Quality of evaluation

The quality of the informed consent evaluation was assessed independently by two authors using seven metrics: (i) the description of participants; (ii) whether or not interviewers were members of the original trial’s staff; (iii) the description of the evaluation method (i.e. by questionnaire or interview); (iv) the description of the questionnaire; (v) the selection of participants (i.e. consecutive participants or a random or cross-sectional selection); (vi) the description of exclusion criteria; and (vii) the timing of the evaluations. Quality scores for the studies included are shown in Appendix A (available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270506278_Online_Only_Supplements_for_Three_decades_of_participants_understanding_of_informed_consent_in_clinical_trials_a_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis).

Study data

Data were extracted for each study on: (i) the year of publication; (ii) the study language and the country where the study was conducted; (iii) the phase of the study; (iv) the baseline characteristics of the study population, including the source of the population, the number of participants and their age, sex and educational level; (v) the medical specialty of the clinical research, including the seriousness of the disease studied; (vi) the method and timing of the informed consent evaluation; (vii) the type of questions participants had to answer; and (viii) the components of informed consent assessed, including understanding of the nature and purpose of the study, knowing that treatments were being compared, therapeutic misconceptions, participants’ ability to name risks, awareness of potential risks and side-effects and understanding of potential benefits, randomization, placebo, the voluntary nature of participation, freedom to withdraw at any time, confidentiality and the availability of alternative treatment.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

If a study investigated more than one population, a data set was created for each population. The proportion of participants who understood the different components of informed consent was pooled across studies using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, United States of America) and was expressed as a percentage with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The heterogeneity of study findings was evaluated using the Q statistic and the I2 test and was considered significant if the P-value was < 0.10. Since studies gave heterogeneous results for all components, the proportion of participants who understood each component was pooled using a random-effects model that included weighting for each study. In examining the effect of covariates on these proportions, we used a subgroup or meta-regression analysis when eight or more studies assessed a particular covariate. Differences between subgroups and trends were considered significant if the P-value of Cochran’s Q test was < 0.05.23 To determine if publication bias was present, we used Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s regression test: a P-value < 0.10 indicated significant publication bias.24 When publication bias was present, we used Duvall and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill method to enhance symmetry by adjusting for studies that appeared to be missing.25–27 The final proportion of participants who understood each component was computed after adjustment for missing studies.

Results

The final analysis included 103 studies: 85 from the database search and 18 from reviewing reference lists.28–130 Ultimately 135 data sets were included because some studies evaluated more than one population (Appendix A). The sample size ranged from 8 to 1789 participants and the response rate to interview questions ranged from 9.3% to 100%. Participants were adults in 95 data sets, parents or guardians in 34, adult and child patients in three, child patients in two and adult patients or parents in one. Overall, 79% (106) of data sets were conducted in middle- or high-income countries – as classified by the World Bank131 – and 67% (90) did not report the phase of the clinical trial. The medical specialty was cancer in 33% (44) of data sets, infectious disease in 14% (19), vaccines in 10%, (13) cardiovascular disease in 7% (9), neurology in 6% (8) and other in 31% (42). Moreover, 98% (132) were published in English and only 1% each in Japanese (1) and French (2). Details of the studies and data sets are presented in Table 1 (available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/93/3/14-141390).

Table 1. Studies and data sets in the meta-analysis of participants’ understanding of informed consent in clinical trials.

| Study | Year | Country (data set, if applicable) | Participants |

Subject | Phase of trial | Involved patients with critical conditions | Evaluation of understanding of informed consent |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | No. | Age,a years | Method | Timing | ||||||

| Ellis28 | 2010 | USA | Adult patients | 171 | 30 (18–50) | Malaria vaccine | I | No | Questionnaire | After ICP |

| Ellis28 | 2010 | Mali | Adult patients | 89 | 27 (18–50) | Malaria vaccine | I | No | Questionnaire | After ICP |

| Ellis28 | 2010 | Mali | Parents or guardians | 700 | ND | Malaria vaccine | I | No | Questionnaire | After ICP |

| Vallely29 | 2010 | United Republic of Tanzania | Adult patients | 99 | ND | Infectious disease | III | No | Interviews | 4 weeks after ICP |

| Hill30 | 2008 | Ghana | Adult and child patients | 1245 | 15–45 (68% were under 35) | Vitamin A supplementation | ND | No | Semi-structured interviews | After ICP |

| Minnies31 | 2008 | South Africa | Parents or guardians | 192 | 26 (16–44) | Infectious disease | ND | No | Questionnaire with staff assistance | Within 1 hour of ICP |

| Kaewpoonsri32 | 2006 | Thailand | Adult patients | 81 | 32 (18–58) | Infectious disease | ND | No | Semi-structured questionnaire and non-participant observation | At third follow-up visit |

| Krosin33 | 2006 | Mali (rural population) | Adult patients | 78 | ND | Malaria vaccine | ND | No | Questionnaire | Within 48 hours of consent |

| Krosin33 | 2006 | Mali (urban population) | Adult patients | 85 | ND | Malaria vaccine | ND | No | Questionnaire | Within 48 hours of consent |

| Moodley34 | 2005 | South Africa | Adult patients | 334 | 68 (60–80) | Influenza vaccine | ND | No | Interviews | 4–12 months after the trial |

| Pace35 | 2005 | Thailand | Adult patients | 141 | > 18 | Infectious disease | III | No | Interviews | Immediately after ICP |

| Pace36 | 2005 | Uganda | Parents or guardians | 347 | ND | Infectious disease | ND | No | Interviews | Immediately after ICP |

| Ekouevi37 | 2004 | Côte d'Ivoire | Adult patients | 55 | 26 | Infectious disease | ND | No | Interviews | ND |

| Joubert38 | 2003 | South Africa | Adult patients | 92 | 27 | Vitamin A supplementation | ND | No | Interviews | Median of 14 months after ICP |

| Lynöe39 | 2001 | Bangladesh | Adult patients | 105 | ND | Iron supplementation | ND | No | Structured questionnaire | After ICP |

| Lynöe40 | 2004 | Sweden | Adult patients | 44 | 67.8 (39–82) | Lipid-lowering treatment | ND | No | Questionnaire | 1 week after ICP |

| Lynöe41 | 1991 | Sweden | Adult and child patients | 43 | 23 (16–35) | Gynaecology | ND | No | Questionnaire by mail | 18 months after the trial |

| Lynöe42 | 2004 | Sweden | ND | 40 | ND | Oncology | ND | No | Questionnaire | ND |

| Lynöe43 | 2001 | Sweden | Adult patients | 26 | 33 (21–50) | Auricular acupuncture | ND | No | Questionnaire | 4 weeks after ICP |

| Lynöe43 | 2001 | Sweden | Adult patients | 16 | 38 (26–45) | Auricular acupuncture | ND | No | Questionnaire | 4 weeks after ICP |

| Leach44 | 1999 | Gambia (rural population) | Parents or guardians | 73 | ND | Haemophilus influenza type B vaccine | ND | No | Interviews | Within 1 week of ICP |

| Leach44 | 1999 | Gambia (urban population) | Parents or guardians | 64 | ND | Haemophilus influenza type B vaccine | ND | No | Interviews | Within 1 week of ICP |

| Pitisuttithum45 | 1997 | Thailand | Adult patients | 33 | 55.3 (43–69) | HIV vaccine | I, II | No | Questionnaire | Prior to ICP |

| Bergenmar46 | 2008 | Sweden | Adult patients | 282 | 60 (32–82) | Oncology | II, III | No | Questionnaire | 75% within 3 days of ICP, 99% within 2 weeks |

| Knifed47 | 2008 | Canada | Adult patients | 21 | 52 (26–65) | Neuro-oncology | I, II, III | No | Face-to-face interviews | Within 1 month of ICP |

| Agrawal48 | 2006 | USA | Adult patients | 163 | 57.7 (IQR: 48–68) | Oncology | I | No | Structured interview | Immediately after ICP |

| Franck49 | 2007 | United Kingdom | Parents or guardians | 109 | ND | 25 paediatric trials | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | Immediately after ICP |

| Gammelgaard50 | 2004 | Denmark (patients participating in trial) | Adult patients | 103 | 60 | Acute myocardial infarction | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | ND |

| Gammelgaard50 | 2004 | Denmark (patients declining participation) | Adult patients | 78 | 61 | Acute myocardial infarction | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | ND |

| Kodish51 | 2004 | USA (participants with nurse present at ICP) | Parents or guardians | 65 | 35 (18–51) | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Interview | Within 48 hours of ICP |

| Kodish51 | 2004 | USA (participants with nurse not present at ICP) | Parents or guardians | 72 | 35 (18–51) | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Interview | Within 48 hours of ICP |

| Criscione52 | 2003 | USA | Adult patients | 30 | 44.9 ± 9.8 | Rheumatology | ND | No | Questionnaire | 7–28 days after ICP |

| Kupst53 | 2003 | USA | Parents or guardians | 20 | ND | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Structured interview | 1 month after ICP |

| Pope54 | 2003 | Canada | Adult patients | 190 | 63 (22–84) | Cardiology, ophthalmology and rheumatology | III | No | Questionnaire | 2 months to 5 years after ICP |

| Schats55 | 2003 | Netherlands (patient consented, patients’ understanding of ICP assessed) | Adult patients | 37 | ND | Neurology | ND | Yes | Structured interview | 7–31 months after ICP |

| Schats55 | 2003 | Netherlands (patient consented, relatives’ understanding of ICP assessed) | Adult patients | 30 | ND | Neurology | ND | Yes | Structured interview | 7–31 months after ICP |

| Schats55 | 2003 | Netherlands (relative consented, patients’ understanding of ICP assessed) | Adult patients | 17 | ND | Neurology | ND | Yes | Structured interview | 7–31 months after ICP |

| Schats55 | 2003 | Netherlands (relative consented, relatives’ understanding of ICP assessed) | Adult patients | 17 | ND | Neurology | ND | Yes | Structured interview | 7–31 months after ICP |

| Simon56 | 2003 | USA (ethnic majority) | Parents or guardians | 60 | 36 (19–51) | Paediatric oncology | III | No | Interview | 48 hours after ICP |

| Simon56 | 2003 | USA (non-English-speaking ethnic minority) | Parents or guardians | 21 | 34 (21–46) | Paediatric oncology | III | No | Interview | 48 hours after ICP |

| Simon56 | 2003 | USA (English-speaking ethnic minority) | Parents or guardians | 27 | 33 (18–45) | Paediatric oncology | III | No | Interview | 48 hours after ICP |

| Joffe57 | 2001 | USA | Adult patients | 207 | 55 (57% were aged 45–64) | Oncology | I, II, III | No | Questionnaire by mail | 3–14 days after ICP |

| Daugherty58 | 1995 | USA | Adult patients | 27 | 58 (32–80) | Oncology | I | No | Structured interview | Before receiving investigational treatment |

| Daugherty59 | 2000 | USA | Adult patients | 144 | 59 (26–82) | Oncology | I | No | Structured interview | Before receiving investigational treatment |

| Hietanen60 | 2000 | Finland | Adult patients | 261 | 65 (48–87) | Oncology | ND | No | Questionnaire by mail | 5–17 months after ICP |

| Montgomery61 | 1998 | United Kingdom | Adult patients | 158 | ND | Anaesthesia | ND | ND | Questionnaire by mail | 6–24 months after ICP |

| van Stuijvenberg62 | 1998 | Netherlands | Parents or guardians | 181 | 34 | Paediatrics | ND | No | Questionnaire | 1–3 years after ICP |

| Harrison63 | 1995 | USA (injection-drug users) | Adult patients | 71 | 37 (18–56) | HIV vaccine | II | No | Questionnaire | Before ICP signature |

| Harrison63 | 1995 | USA (injection-drug users and other high-risk individuals) | Adult patients | 71 | 37 (18–56) | HIV vaccine | II | No | Questionnaire | Before ICP signature |

| Harth64 | 1995 | Australia | Parents or guardians | 62 | 31 | Asthma | ND | No | Interview by telephone | 6–9 months after entering trial |

| Estey65 | 1994 | Canada | Adult patients | 29 | 58 (43–70) | Drug trial | ND | No | Interview | 1–6 weeks after ICP |

| Howard66 | 1981 | USA | Adult patients | 64 | 55 (30–69) | Acute myocardial infarction | ND | Yes | Interview | 2 weeks to 15 months after ICP |

| Griffin67 | 2006 | USA | Adult patients | 1789 | 65 (53% were aged 60–69) | Cholesterol treatment | ND | No | Interview | 5.1 years after trial |

| Guarino68 | 2006 | USA | Adult patients | 1086 | 40.7 (27–72) | Gulf War veterans’ illnesses | ND | No | Questionnaire | ND |

| Barrett69 | 2005 | USA | Adult patients | 8 | 11.9 (39–76) | Oncology | II, III | No | Questionnaire | ND |

| Sugarman70 | 2005 | USA | Adult patients | 627 | 67 ± 7.2 | Several trials on different diseases | ND | No | Interview by telephone | Right after ICP |

| Simon71 | 2004 | USA | Adult patients | 79 | 51.9 ± 11.2 | Oncology | III | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Simon71 | 2004 | USA | Adult patients | 140 | 35.4 ± 7.6 | Oncology | III | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Pentz72 | 2002 | USA | Adult patients | 100 | 56 (25–79) | Oncology | I | No | Structured interview in person or by phone or mail | ND |

| Cohen73 | 2001 | USA | Adult patients | 46 | 54.9 ± 8.9 | Oncology | I | No | Questionnaire | Before treatment |

| Fortney74 | 1999 | USA | Adult patients | 15 | ND | Gynaecology | ND | No | Structured interview | 9–39 days after ICP |

| Fortney74 | 1999 | Africa | Adult patients | 17 | ND | Gynaecology | ND | No | Structured interview | 26–250 days after ICP |

| Fortney74 | 1999 | Latin America group I | Adult patients | 19 | ND | Gynaecology | ND | No | Structured interview | 26–250 days after ICP |

| Fortney74 | 1999 | Latin America group II | Adult patients | 19 | ND | Gynaecology | ND | No | Structured interview | 26–250 days after ICP |

| Hutchison75 | 1998 | United Kingdom | Adult patients | 28 | 55.4 ± 8.8 | Oncology | I | No | Structured interview | 2–4 weeks after ICP |

| Négrier76 | 1995 | France | Adult patients | 24 | 56 | Oncology | II | No | Written questionnaire | Immediately after ICP |

| Tankanow77 | 1992 | USA | Adult patients | 98 | 44 (18–76) | Drug trials | ND | ND | Interview based on a questionnaire | 72 hours after ICP |

| Rodenhuis78 | 1984 | Netherlands | Adult patients | 10 | 56 (20–72) | Oncology | I | No | Structured interview | 1–6 months after ICP |

| Penman79 | 1984 | USA | Adult patients | 144 | 55 (18–65) | Oncology | II, III | No | Structured interview | 1–3 weeks after ICP |

| Goodman80 | 1984 | United Kingdom (first study) | Adult patients | 14 | 66 (50–81) | Anaesthesia | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | Postoperative phase of the study |

| Goodman80 | 1984 | United Kingdom (second study) | Adult patients | 18 | ND | Anaesthesia | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | Before discharge from hospital |

| Riecken81 | 1982 | USA | Adult patients | 156 | ND | 50 clinical trials | ND | ND | Interview | < 10 weeks after ICP |

| Bergler82 | 1980 | USA | Adult patients | 39 | 55 | Anti-hypertensive treatment | ND | No | Structured interview | Immediately after ICP |

| Ritsuko83 | 2006 | Japan | Adult patients | 279 | 65 | Clinical trials | II, III | ND | Questionnaire | 1 month to 2 years after ICP |

| PENTA84 | 1999 | Several countries | Parents or guardians | 84 | ND | Drug trial | ND | No | Questionnaire | Before unblinding the individual child’s therapy |

| Ballard85 | 2004 | USA (mothers) | Parents or guardians | 35 | 26.3 (16–43) | Paediatrics | ND | No | Questionnaire | 3–28 months after ICP |

| Ballard85 | 2004 | USA (fathers) | Parents or guardians | 21 | 26.3 (16–43) | Paediatrics | ND | No | Questionnaire | 3–28 months after ICP |

| Ballard85 | 2004 | USA (mothers and fathers) | Parents or guardians | 8 | 26.3 (16–43) | Paediatrics | ND | No | Questionnaire | 3–28 months after ICP |

| Bertoli86 | 2007 | Argentina | Adult patients | 105 | 56.3 ± 11.8 | Rheumatology | III, IV | No | Questionnaire | ND |

| Burgess87 | 2003 | Canada (prospective study) | Parents or guardians | 29 | 30 (21–41) for mothers and 33.4 for fathers | Neonatology | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | Prospective study |

| Burgess87 | 2003 | Canada (retrospective evaluation of ICP) | Parents or guardians | 44 | 29.5 (14–40) for mothers and 33.4 for fathers | Neonatology | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | > 1 year after ICP |

| Chaisson88 | 2011 | Botswana (English speakers) | Adult patients | 969 | 33 | Infectious disease | ND | No | Questionnaire | Within 30 days of ICP |

| Chaisson88 | 2011 | Botswana (Setswana speakers) | Adult patients | 969 | 33 | Infectious disease | ND | No | Questionnaire | Within 30 days of ICP |

| Chappuy89 | 2010 | France | Parents or guardians | 43 | ND | Paediatric oncology | III | No | Semi-structured interview | After ICP |

| Chappuy90 | 2013 | France | Parents or guardians | 40 | ND | Oncology | III | No | Semi-structured interview | After study inclusion |

| Chappuy91 | 2006 | France | Parents or guardians | 68 | ND | HIV infection or oncology | I, II, III, IV | No | Semi-structured interview | 21 days to 2 years after ICP |

| Chappuy92 | 2008 | France | Child patients | 29 | 13.6 ± 2.8 | HIV infection or oncology | I, II, III, IV | No | Semi-structured interview | After diagnosis |

| Chenaud93 | 2006 | Switzerland | Adult patients | 44 | 54 ± 22 | Surgical intensive care unit | ND | Yes | Interview | Mean of 10 days (standard deviation: 2) after ICP |

| Chu94 | 2012 | Republic of Korea | Adult patients | 140 | 47.2 ± 14 | Several diseases | I, II, III, IV | No | Self-administered questionnaire | ND |

| Constantinou95 | 2012 | Australia (patients participating in trial) | Adult patients | 20 | 72.2 ± 10.3 | Ophthalmology | ND | No | Interview | ND |

| Constantinou95 | 2012 | Australia (patients declining participation) | Adult patients | 20 | 73.1 ± 6.8 | Ophthalmology | ND | No | Interview | ND |

| Cousino96 | 2012 | USA (ethnic majority) | Parents or guardians | 60 | 42 (23–66) | Paediatric oncology | I | No | Interview | ND |

| Cousino96 | 2012 | USA (ethnic minority) | Parents or guardians | 60 | 42 (23–66) | Paediatric oncology | I | No | Interview | ND |

| Durand-Zaleski97 | 2008 | France | Adult patients and parents or guardians | 279 | 49.5 (39–58) for patients and 40 (35–45) for parents and guardians | ND | ND | No | Structured interview | ND |

| Eiser98 | 2005 | United Kingdom | Parents or guardians | 50 | ND | Oncology | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | 3–5 months after diagnosis |

| Featherstone99 | 1998 | United Kingdom | Adult patients | 20 | ND | Urinary retention treatment | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | Seven patients within 3 months and five within 5 months of randomization; eight patients after receiving treatment |

| Hazen100 | 2007 | USA (ethnic majority) | Parents or guardians | 79 | ND | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Interview | Within 48 hours of ICP |

| Hazen100 | 2007 | USA (ethnic minority) | Parents or guardians | 61 | ND | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Interview | Within 48 hours of ICP |

| Hereu101 | 2010 | Spain (urgent cases) | Adult patients | 24 | 52 (22–88) | 40 therapeutic trials | II, III, IV | Yes | Structured interview | Within 3 months of ICP |

| Hereu101 | 2010 | Spain (non-urgent cases) | Adult patients | 115 | 52 (22–88) | 40 therapeutic trials | II, III, IV | No | Structured interview | Within 3 months of ICP |

| Hofmeijer102 | 2007 | Netherlands (extremely urgent treatment) | Adult patients | 28 | 48 ± 8 | Neurology | ND | Yes | Interview | Median of 13 days (range: 10–16) after ICP |

| Hofmeijer102 | 2007 | Netherlands (less urgent treatment) | Adult patients | 30 | 69 ± 13 | Neurology | ND | Yes | Interview | Median of 13 days (range: 10–16) after ICP |

| Itoh103 | 1997 | Japan | Adult patients | 32 | 58 (30–68) | Oncology | I | No | Questionnaire | After ICP and before drug treatment |

| Jenkins104 | 2000 | United Kingdom (patients participating in trial) | Adult patients | 147 | 55 (all > 25) | Oncology | ND | No | Postal questionnaire | ND |

| Jenkins104 | 2000 | United Kingdom (patients declining participation in trial) | Adult patients | 51 | 55 (all > 25) | Oncology | ND | No | Postal questionnaire | ND |

| Kass105 | 2005 | Two African and one Caribbean country | Adult patients | 26 | Two thirds were 20–30 and one third were 31–40 | Infectious disease | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Kenyon106 | 2006 | United Kingdom | Adult patients | 20 | ND | Gynaecology | ND | Yes | Interview | ND |

| Kiguba107 | 2012 | Uganda | Adult patients | 235 | 38.2 ± 7.5 | Infectious disease | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | After initial or repeat ICP |

| Lidz108 | 2004 | USA | Adult patients | 155 | 55 (all > 18) | 40 trials on several diseases | I, II, III, IV | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Leroy109 | 2011 | France | Adult patients | 75 | 54.7 (28–82) | Oncology | II, III | No | Self-assessment questionnaire | ND |

| Levi110 | 2000 | USA | Parents or guardians | 22 | ND | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Manafa111 | 2007 | Nigeria | Adult patients | 88 | 39.2 (26–62) | Infectious disease | ND | No | Questionnaire | 2 months after enrolment in trial |

| McNally112 | 2001 | United Kingdom | Parents or guardians | 29 | 32 | Infectious disease | ND | No | Questionnaire | ND |

| Mangset113 | 2008 | Norway | Adult patients | 11 | 69.9 ± 8.1 | Neurology | III | Yes | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Meneguin114 | 2010 | Brazil | Adult patients | 80 | 58.7 ± 9.3 | Cardiology | II, III, IV | No | Semi-structured interview | 6 months to 4 years after completion of trial |

| Miller115 | 2013 | USA | Adult and child patients | 20 | 17.8 ± 2.4 | Paediatric oncology | I | No | Structured interview | Immediately after ICP |

| Mills116 | 2003 | United Kingdom | Adult patients | 21 | 60 (50–69) | Oncology | ND | No | Interview | Approximately10 days after ICP |

| Nurgat117 | 2005 | United Kingdom | Adult patients | 38 | 60 (37–79) | Oncology | I, II | No | Questionnaire by mail | Before or during the first treatment cycle |

| Ockene118 | 1991 | USA | Adult patients | 28 | ND | Cardiology | I | Yes | Interview based on a questionnaire | After ICP |

| Petersen119 | 2013 | Germany (patients participating in trial) | Parents or guardians | 767 | ND | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Questionnaire by mail | ND |

| Petersen119 | 2013 | Germany (patients declining participation) | Parents or guardians | 40 | ND | Paediatric oncology | ND | No | Questionnaire by mail | ND |

| Queiroz da Fonseca120 | 1999 | Brazil | Adult patients | 66 | 18–49 | HIV vaccine | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Russell121 | 2005 | Australia (Aborigines) | Adult patients | 20 | 95% were > 16 | Pneumococcal vaccine | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | Immediately after ICP |

| Russell121 | 2005 | Australia (non-Aborigines) | Adult patients | 20 | 100% were > 16 | Pneumococcal vaccine | ND | No | Semi-structured interview | Immediately after ICP |

| Schaeffer122 | 1996 | USA (phase1) | Adult patients | 9 | 53 ± 14.7 | Oncology | I | No | Questionnaire | 24 hours after study inclusion |

| Schaeffer122 | 1996 | USA (phase 2) | Adult patients | 36 | 56 ± 8.9 | Oncology | I | No | Questionnaire | 24 hours after study inclusion |

| Schaeffer122 | 1996 | USA (phase 3) | Adult patients | 28 | 33 ± 6.6 | Infectious disease | I | No | Questionnaire | 24 hours after study inclusion |

| Coulibaly-Traore123 | 2003 | France | Adult patients | 57 | 25 (18–42) | HIV vaccine | ND | No | Interview | 90–180 days after ICP |

| Ducrocq124 | 2000 | France | Adult patients | 72 | 62 (29–85) | Neurology | ND | No | Interview | 6–24 hours after study inclusion |

| Schutta125 | 2000 | USA | Adult patients | 8 | 57 (42–72) | Oncology | I | No | Interview | Immediately after ICP |

| Snowdon126 | 1997 | United Kingdom | Parents or guardians | 71 | 30.5 (22–44) | Neonatology | ND | Yes | Semi-structured interview | Different times after recruitment to the trial |

| Stenson127 | 2004 | United Kingdom | Parents or guardians | 99 | ND | Neonatology | ND | Yes | Questionnaire | 18 months after the study finished |

| Unguru128 | 2010 | USA | Child patients | 37 | 13.6 (7–19) | Paediatric oncology | I, II, III, IV | No | Semi-structured interview | ND |

| Yoong129 | 2011 | Australia | Adult patients | 102 | ND | Oncology | I, II, III | No | Questionnaire | ND |

| Verheggen130 | 1996 | Netherlands | Adult patients | 198 | ND | 26 trials | ND | No | Questionnaire | 4 weeks after ICP |

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; ICP: informed consent process; IQR: interquartile range; ND: not determined.

a Ages are given as a mean alone, a mean ± standard deviation, a range or a median (range), unless otherwise stated.

Understanding of informed consent

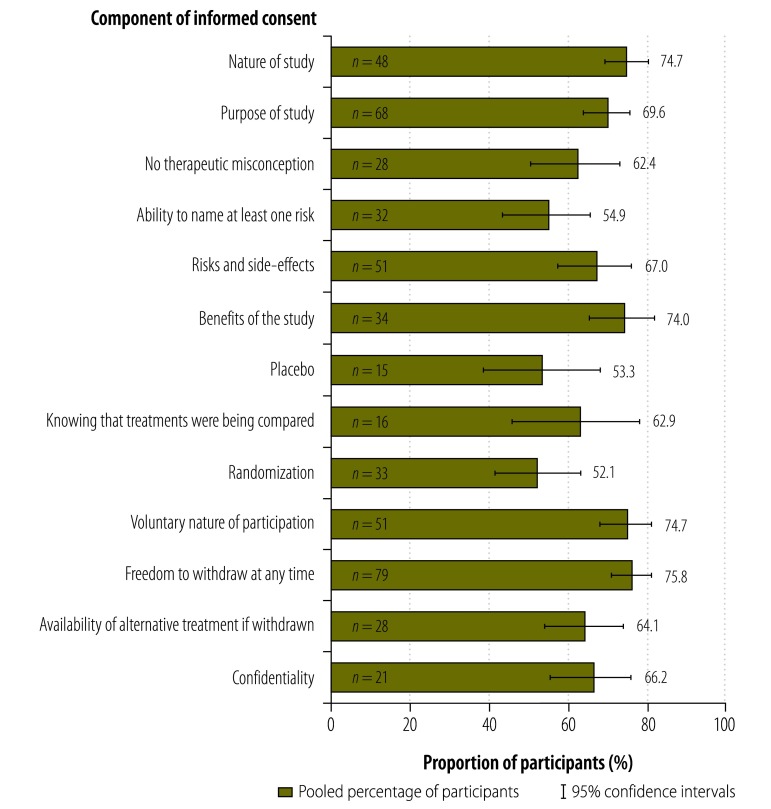

The number of data sets that covered each component of informed consent is shown in Appendix B (available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270506278_Online_Only_Supplements_for_Three_decades_of_participants_understanding_of_informed_consent_in_clinical_trials_a_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis). Understanding of freedom to withdraw at any time was investigated in the largest number of studies (n = 79), whereas understanding of placebo was investigated in the smallest number (n = 15). Our analysis showed some variation in the proportion of participants who understood different components of informed consent. The highest proportions were 75.8% (95% CI: 70.6–80.3) for freedom to withdraw from the study at any time, 74.7% (95% CI: 68.8–79.8) for the nature of study, 74.7% (95% CI: 67.9–80.5) for the voluntary nature of participation and 74.0% (95% CI: 65.0–81.3) for potential benefits (Fig. 2 and Appendix B). Lower proportions were 69.6% (95% CI: 63.5–75.1) for the purpose of the study, 67.0% (95% CI: 57.4–75.4) for potential risks and side-effects, 66.2% (95% CI: 55.3–75.7) for confidentiality, 64.1% (95% CI: 53.7–73.4) for the availability of alternative treatment if withdrawn and 62.9% (95% CI: 45.5–77.5) for knowing that treatments were being compared. In addition, 62.4% (95% CI: 50.1–73.2) had no therapeutic misconceptions. The lowest proportions were 54.9% (95% CI: 43.3–65.0) for naming at least one risk, followed by 53.3% (95% CI: 38.4–67.6) for understanding of placebo and 52.1% (95% CI: 41.3–62.7) for understanding of randomization.

Fig. 2.

Participants’ understanding of components of informed consent in clinical trials, by meta-analysisa

a The number of studies included in the evaluation of each component is given.

Effect of covariates

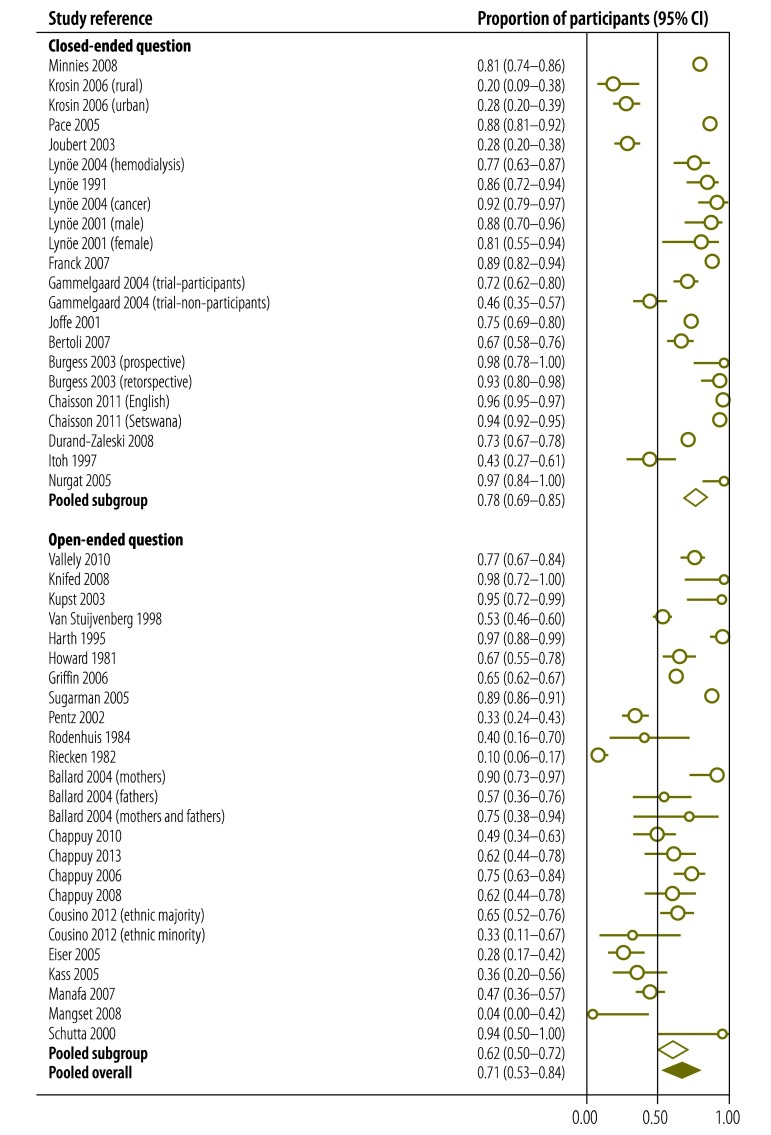

We performed a meta-regression analysis to evaluate the influence of particular covariates on the proportion of participants who understood informed consent (Table 2). We found that gender had no effect but that, importantly, significantly fewer patients from low-income countries than from middle- and high countries understood randomization, the voluntary nature of participation and freedom to withdraw at any time. In addition, critically ill patients were significantly less likely to understand the nature or benefits of the study or confidentiality or to be able to name at least one risk. However, older participants were more likely to understand the nature of the study and freedom to withdraw at any time. A lower educational level was associated with a reduced likelihood of understanding the nature of the study, placebo, randomization and freedom to withdraw at any time. Participants in phase-I clinical trials were less likely than participants in phase-II, -III or -IV trials to understand the purpose of the study and were more likely to have therapeutic misconceptions. Participants in phase-I trials were also more likely to understand potential risks and side-effects and freedom to withdraw at any time. Participants assessed using open-ended questions were less likely to understand the purpose of the study (Fig. 3), the voluntary nature of participation or freedom to withdraw at any time or to be able to name at least one risk. Additionally, the later the evaluation of understanding was carried out, the less likely the participant was to understand confidentiality or to be able to name at least one risk. The quality of the evaluation did not influence understanding.

Table 2. Influencea of covariates on participants’ understanding of informed consent in clinical trials.

| Component of informed consent | Effect of covariate on understanding of component |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial |

Participants |

Evaluation of understanding of informed consent |

||||||||||

| Publication yearb | Low-income country | Phase-I study | Female sex | Older ageb | Critically ill | Low educational levelb | Late evaluationb | Open-ended question used | Quality of evaluationb | |||

| Nature of the study | None | None | None | None | Increased | Decreased | Decreased | None | None | None | ||

| Purpose of the study | None | None | Decreased | None | None | None | None | None | Decreased | None | ||

| No therapeutic misconceptionc | None | NDd | Decreased | None | None | ND | None | None | None | None | ||

| Ability to name at least one risk | None | None | None | None | None | Decreased | None | Decreased | Decreased | None | ||

| Risks and side-effects | None | None | Increased | None | None | None | None | None | None | None | ||

| Benefits of the study | None | None | None | None | None | Decreased | None | None | None | None | ||

| Placebo | None | None | ND | ND | None | ND | Decreased | None | ND | None | ||

| Knowing that treatments were being compared | None | ND | ND | None | None | ND | None | None | ND | None | ||

| Randomization | None | Decreased | ND | None | None | None | Decreased | None | None | None | ||

| Voluntary nature of participation | None | Decreased | ND | None | None | None | None | None | Decreased | None | ||

| Freedom to withdraw at any time | None | Decreased | Increased | None | Increased | None | Decreased | None | Decreased | None | ||

| Availability of alternative treatment if withdrawn | None | None | None | None | None | ND | None | None | None | None | ||

| Confidentiality | None | None | ND | ND | None | Decreased | None | Decreased | ND | None | ||

ND: not determined.

a The influence of the covariate on participants’ understanding of the component of informed consent was evaluated by meta-regression analysis.

b Continuous variable.

c No lack of awareness of the uncertainty of success.

d The effect was not determined because there were fewer than five studies per subgroup or fewer than 10 for the regression analysis.

Fig. 3.

Effect of using an open-ended questiona on participants’ understanding of the purpose of a clinical studyb

CI: confidence interval.

a Participants’ understanding of components of informed consent was assessed using open-ended or closed-ended questions.

b The pooled proportion of participants who understood the purpose of the study was calculated using random-effects models for those assessed using both open-ended and closed-ended questions.

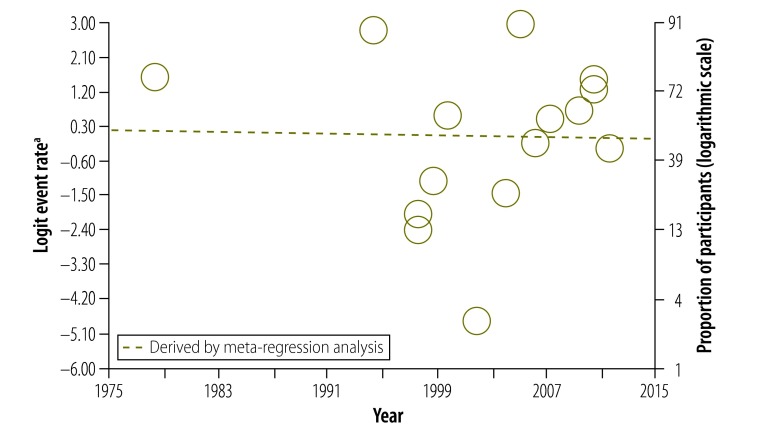

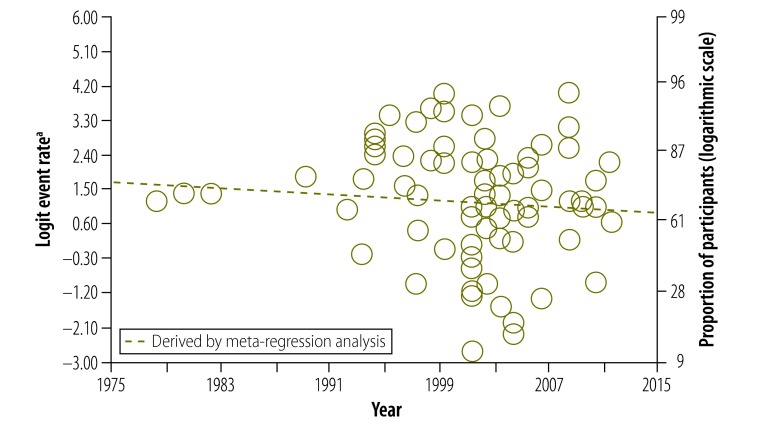

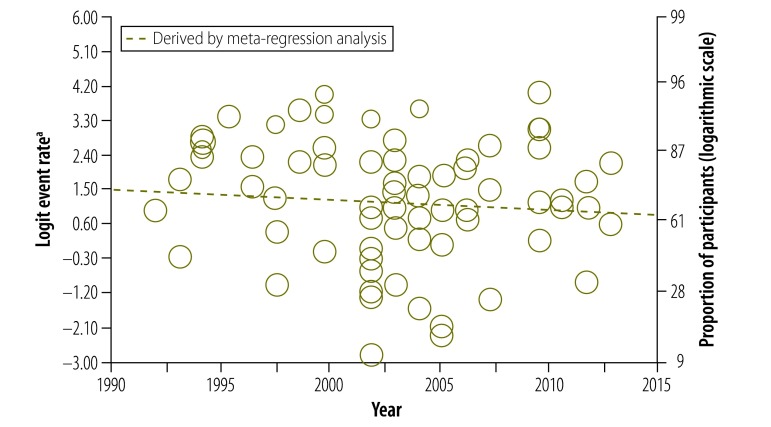

Our data also provided us with the opportunity to analyse how study participants’ understanding of informed consent had changed over 30 years. Surprisingly, there was no significant change in understanding of any component (Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Fig. 6). In particular, we were interested in the past 20 years, after the World Health Organization introduced guidelines for good clinical practice in trials.132 After removing four early studies, we again found no significant change in understanding of any component, including the freedom to withdraw (Fig. 7). Furthermore, there was no significant change in understanding of any component over the past 13 years in all studies combined or in subgroups of participants, including those assessed using open-ended questions, those assessed using closed-ended questions and those in middle- and high-income countries assessed using closed-ended questions (Appendices C, D, E and F, respectively, available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/270506278_Online_Only_Supplements_for_Three_decades_of_participants_understanding_of_informed_consent_in_clinical_trials_a_systematic_review_and_meta-analysis).

Fig. 4.

Participants’ understanding of the potential risks and side-effects of participating in a clinical study

a The logit event rate is the natural logarithm of the event rate divided by (1 – event rate), where the event rate is the proportion of study participants who understood the potential risks and side-effects of participating in a clinical study.

Fig. 5.

Participants’ understanding of placebo in clinical studies

a The logit event rate is the natural logarithm of the event rate divided by (1 – event rate), where the event rate is the proportion of study participants who understood placebo.

Fig. 6.

Participants’ understanding of their freedom to withdraw from a study at any time

a The logit event rate is the natural logarithm of the event rate divided by (1 – event rate), where the event rate is the proportion of study participants who understood they were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Fig. 7.

Participants’ understanding of their freedom to withdraw from a study at any time, after introduction of WHO guidelines for good clinical practice in trials132

a The logit event rate is the natural logarithm of the event rate divided by (1 – event rate), where the event rate is the proportion of study participants who understood they were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Discussion

Obtaining informed consent from participants in clinical research is essential because it promotes their welfare and ensures their rights.9,133 However, participants must have a good understanding of what informed consent entails. Our meta-analysis indicates that around 75% of individuals understood the nature of the study, their right to refuse to participate, their right to withdraw at any time and the direct benefits of participation. This percentage is higher than the figure of around 50% found in a previous systematic review18 probably because we included only clinical trials, excluded studies of patients with cognitive deficits and weighted the meta-analysis to account for heterogeneous data.

Our data also highlight the difficulty participants had in understanding particular components of informed consent, such as randomization and the use of placebo. Moreover, although participants were aware of potential risks and side-effects, they were less likely to be able to name at least one risk and, although they understood the benefits of participating in a study, they were less aware of the uncertainty of these benefits (i.e. had therapeutic misconceptions). These findings were also noted in previous studies.18,19,134–137 They are, perhaps, not surprising since a participant’s understanding depends, to a certain degree, on their literacy as well as on the duration of the informed consent process and the explanatory skills of the researchers.138–140

In addition, the meta-regression was able to identify differences in understanding of informed consent between population groups. Older participants more often than younger participants understood the nature of the study and freedom to withdraw at any time. The reason for this difference requires further study. As noted in a previous systematic review,19 participants from developing countries were less likely than others to understand the voluntary nature of participation and freedom to withdraw at any time. It is possible that patients in these countries dare not refuse to join or dare not withdraw from a study because they fear their doctor’s disapproval.141 Participants from developing countries and those with a low level of literacy were less likely to understand randomization.

Phase-I clinical trials are usually conducted in small numbers of participants to test a drug’s safety and dose range. Consequently, it was expected that participants in phase-I trials would be less likely than those in more advanced trials to understand the purpose of the study or that the benefits were uncertain. In contrast, participants in phase-I trials were more likely to be aware of potential risks and of their freedom to withdraw at any time.

Compared with the use of open-ended questions to evaluate participants' understanding, the use of closed-ended questions was associated with higher rates of understanding of the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation and freedom to withdraw and with a greater likelihood of being able to name at least one risk. However, the use of closed-ended questions could have led to understanding being overestimated because respondents had to choose from a limited number of possible answers and did not have to think clearly about the issues.142 Consequently, the use of open-ended questions may have reflected better the true extent of understanding since respondents had to put their understanding into words.143

Finally, an unexpected finding of our analysis was that understanding of the potential risks and side-effects of trials, of placebo and of freedom to withdraw had not changed over 30 years. This is despite considerable progress in medical research methods over this time144 and many attempts made to improve the quality of informed consent.145 There are four possible explanations: (i) the maximum proportion of participants who understand these concepts has been reached; (ii) the increasing complexity of clinical trials has made the informed consent process longer and more difficult to understand; (iii) not enough effort has been put into enhancing the quality of the informed consent process; and (iv) our analysis did not have the statistical power to detect a significant increase in understanding. In fact, the best way to improve understanding of informed consent is still debated. A recent meta-analysis of interventions for improving understanding found that enhanced consent forms and extended discussions led to significant increases in understanding whereas multimedia approaches did not.146 In other words, simple measures such as well formatted, easily readable consent forms and intensive discussions with participants may be more effective than more complex measures.140,146–148

Although an understanding of all the components of informed consent we investigated is required for patients to make a decision on study participation, some components were assessed more often than others. We found a good correlation between the likelihood that a participant would understand a specific component of informed consent and the number of studies that investigated understanding of that component (Appendix G). This suggests either that it was simpler to evaluate understanding of some components or that some components were more important.

One limitation of our study is that we were not able to analyse the effect on understanding of informed consent of the presence of a nurse during the informed consent process, of the duration of the process or of participants choosing not to take part in a clinical trial because only a small number of studies investigated these factors. Moreover, only 79 of the 135 data sets gave information on whether the interviewers were investigators in the original clinical trial. Hence, we were not able to analyse the effect of this factor on the results. Another limitation is that we included studies of children because they have the right to decide whether to participate.149,150 However, the number of studies involving children was small and our sensitivity analysis showed that removing these studies did not influence the pooled results. Although we found a high level of heterogeneity across studies for understanding of all components of informed consent and although Cox et al. suggest that, in these circumstances, individual studies should be described rather than combined in a meta-analysis,151 we, like other groups, chose to perform a meta-analysis with a regression analysis and subgroup analysis to gain a better insight into how covariates affect understanding.152–154

In conclusion, we found that most participants in clinical trials understood fundamental components of informed consent such as the nature and benefits of the study, freedom to withdraw at any time and the voluntary nature of participation. Understanding of other components, such as randomization and placebo, was less satisfactory and has not improved over 30 years. Our findings suggest that investigators could make a greater effort to help research participants achieve a complete understanding of informed consent. This would ensure that participants’ decision-making is meaningful and that their interests are protected.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Grodin MA, Annas GJ. Legacies of Nuremberg. Medical ethics and human rights. JAMA. 1996. November 27;276(20):1682–3. 10.1001/jama.1996.03540200068035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emanuel EJ, Wendler D, Grady C. What makes clinical research ethical? JAMA. 2000. May 24-31;283(20):2701–11. 10.1001/jama.283.20.2701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annas GJ. Doctors, patients, and lawyers–two centuries of health law. N Engl J Med. 2012. August 2;367(5):445–50. 10.1056/NEJMra1108646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jefford M, Moore R. Improvement of informed consent and the quality of consent documents. Lancet Oncol. 2008. May;9(5):485–93. 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70128-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Will JF. A brief historical and theoretical perspective on patient autonomy and medical decision making: Part II: The autonomy model. Chest. 2011. June;139(6):1491–7. 10.1378/chest.11-0516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wendler D. How to enroll participants in research ethically. JAMA. 2011. April 20;305(15):1587–8. 10.1001/jama.2011.421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glickman SW, McHutchison JG, Peterson ED, Cairns CB, Harrington RA, Califf RM, et al. Ethical and scientific implications of the globalization of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 2009. February 19;360(8):816–23. 10.1056/NEJMsb0803929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rivera R, Borasky D, Rice R, Carayon F, Wong E. Informed consent: an international researchers’ perspective. Am J Public Health. 2007. January;97(1):25–30. 10.2105/AJPH.2005.081604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013. November 27;310(20):2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boga M, Davies A, Kamuya D, Kinyanjui SM, Kivaya E, Kombe F, et al. Strengthening the informed consent process in international health research through community engagement: The KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme Experience. PLoS Med. 2011. September;8(9):e1001089. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.del Carmen MG, Joffe S. Informed consent for medical treatment and research: a review. Oncologist. 2005. September;10(8):636–41. 10.1634/theoncologist.10-8-636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weijer C, Grimshaw JM, Eccles MP, McRae AD, White A, Brehaut JC, et al. ; Ottawa Ethics of Cluster Randomized Trials Consensus Group. The Ottawa Statement on the Ethical Design and Conduct of Cluster Randomized Trials. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001346. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sreenivasan G. Does informed consent to research require comprehension? Lancet. 2003. December 13;362(9400):2016–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15025-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lad PM, Dahl R. Audit of the informed consent process as a part of a clinical research quality assurance program. Sci Eng Ethics. 2014. June;20(2):469–79. 10.1007/s11948-013-9461-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson V. Patient comprehension of informed consent. J Perioper Pract. 2013. Jan-Feb;23(1-2):26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhutta ZA. Beyond informed consent. Bull World Health Organ. 2004. October;82(10):771–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falagas ME, Korbila IP, Giannopoulou KP, Kondilis BK, Peppas G. Informed consent: how much and what do patients understand? Am J Surg. 2009. September;198(3):420–35. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mandava A, Pace C, Campbell B, Emanuel E, Grady C. The quality of informed consent: mapping the landscape. A review of empirical data from developing and developed countries. J Med Ethics. 2012. June;38(6):356–65. 10.1136/medethics-2011-100178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aromataris E, Riitano D. Constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. A guide to the literature search for a systematic review. Am J Nurs. 2014. May;114(5):49–56. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000446779.99522.f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Protection of human subjects. Code Fed Requl Public Welfare. Washington: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1995 Oct 1;Title 4s: sections 46-101 to 46-409. [PubMed]

- 22.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000. April 19;283(15):2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sedgwick P. Meta-analyses: heterogeneity and subgroup analysis. BMJ. 2013. June 24;346 jun24 2:f4040 10.1136/bmj.f4040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peters JL, Sutton AJ, Jones DR, Abrams KR, Rushton L. Comparison of two methods to detect publication bias in meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006. February 8;295(6):676–80. 10.1001/jama.295.6.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000. June;56(2):455–63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mengoli C, Cruciani M, Barnes RA, Loeffler J, Donnelly JP. Use of PCR for diagnosis of invasive aspergillosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009. February;9(2):89–96. 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70019-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufert JM, O'Neil J. Culture, power and informed consent: the impact of Aboriginal health interpreters on decision-making. In: Coburn D, D'Arcy C, Torrance G, editors. Health and Canadian society: sociological perspectives. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellis RD, Sagara I, Durbin A, Dicko A, Shaffer D, Miller L, et al. Comparing the understanding of subjects receiving a candidate malaria vaccine in the United States and Mali. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010. October;83(4):868–72. 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.10-0062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vallely A, Lees S, Shagi C, Kasindi S, Soteli S, Kavit N, et al. ; Microbicides Development Programme (MDP). How informed is consent in vulnerable populations? Experience using a continuous consent process during the MDP301 vaginal microbicide trial in Mwanza, Tanzania. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11(1):10. 10.1186/1472-6939-11-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill Z, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Odei-Danso S, Kirkwood B. Informed consent in Ghana: what do participants really understand? J Med Ethics. 2008. January;34(1):48–53. 10.1136/jme.2006.019059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minnies D, Hawkridge T, Hanekom W, Ehrlich R, London L, Hussey G. Evaluation of the quality of informed consent in a vaccine field trial in a developing country setting. BMC Med Ethics. 2008;9(1):15. 10.1186/1472-6939-9-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaewpoonsri N, Okanurak K, Kitayaporn D, Kaewkungwal J, Vijaykadga S, Thamaree S. Factors related to volunteer comprehension of informed consent for a clinical trial. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006. September;37(5):996–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krosin MT, Klitzman R, Levin B, Cheng J, Ranney ML. Problems in comprehension of informed consent in rural and peri-urban Mali, West Africa. Clin Trials. 2006;3(3):306–13. 10.1191/1740774506cn150oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moodley K, Pather M, Myer L. Informed consent and participant perceptions of influenza vaccine trials in South Africa. J Med Ethics. 2005. December;31(12):727–32. 10.1136/jme.2004.009910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pace C, Emanuel EJ, Chuenyam T, Duncombe C, Bebchuk JD, Wendler D, et al. The quality of informed consent in a clinical research study in Thailand. IRB. 2005. Jan-Feb;27(1):9–17. 10.2307/3563866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pace C, Talisuna A, Wendler D, Maiso F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Bakyaita N, et al. Quality of parental consent in a Ugandan malaria study. Am J Public Health. 2005. July;95(7):1184–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ANRS1201/1202 Ditrame Plus Study Group. Obtaining informed consent from HIV-infected pregnant women, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. AIDS. 2004. July 2;18(10):1486–8. 10.1097/01.aids.0000131349.22032.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joubert G, Steinberg H, van der Ryst E, Chikobvu P. Consent for participation in the Bloemfontein vitamin A trial: how informed and voluntary? Am J Public Health. 2003. April;93(4):582–4. 10.2105/AJPH.93.4.582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynöe N, Hyder Z, Chowdhury M, Ekström L. Obtaining informed consent in Bangladesh. N Engl J Med. 2001. February 8;344(6):460–1. 10.1056/NEJM200102083440617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynöe N, Näsström B, Sandlund M. Study of the quality of information given to patients participating in a clinical trial regarding chronic hemodialysis. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2004;38(6):517–20. 10.1080/00365590410033362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lynöe N, Sandlund M, Dahlqvist G, Jacobsson L. Informed consent: study of quality of information given to participants in a clinical trial. BMJ. 1991. September 14;303(6803):610–3. 10.1136/bmj.303.6803.610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynöe N, Boman K, Andersson H, Sandlund M. Informed consent and participants’ inclination to delegate decision-making to the doctor. Acta Oncol. 2004;43(8):769. 10.1080/02841860410002734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lynöe N, Sandlund M, Jacobsson L. Informed consent in two Swedish prisons: a study of quality of information and reasons for participating in a clinical trial. Med Law. 2001;20(4):515–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leach A, Hilton S, Greenwood BM, Manneh E, Dibba B, Wilkins A, et al. An evaluation of the informed consent procedure used during a trial of a Haemophilus influenzae type B conjugate vaccine undertaken in the Gambia, West Africa. Soc Sci Med. 1999. January;48(2):139–48. 10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00317-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pitisuttithum P, Migasena S, Laothai A, Suntharasamai P, Kumpong C, Vanichseni S. Risk behaviours and comprehension among intravenous drug users volunteered for HIV vaccine trial. J Med Assoc Thai. 1997. January;80(1):47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bergenmar M, Molin C, Wilking N, Brandberg Y. Knowledge and understanding among cancer patients consenting to participate in clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 2008. November;44(17):2627–33. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Knifed E, Lipsman N, Mason W, Bernstein M. Patients’ perception of the informed consent process for neurooncology clinical trials. Neuro-oncol. 2008. June;10(3):348–54. 10.1215/15228517-2008-007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agrawal M, Grady C, Fairclough DL, Meropol NJ, Maynard K, Emanuel EJ. Patients’ decision-making process regarding participation in phase I oncology research. J Clin Oncol. 2006. September 20;24(27):4479–84. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Franck LS, Winter I, Oulton K. The quality of parental consent for research with children: a prospective repeated measure self-report survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007. May;44(4):525–33. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gammelgaard A, Mortensen OS, Rossel P; DANAMI-2 Investigators. Patients’ perceptions of informed consent in acute myocardial infarction research: a questionnaire based survey of the consent process in the DANAMI-2 trial. Heart. 2004. October;90(10):1124–8. 10.1136/hrt.2003.021931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kodish E, Eder M, Noll RB, Ruccione K, Lange B, Angiolillo A, et al. Communication of randomization in childhood leukemia trials. JAMA. 2004. January 28;291(4):470–5. 10.1001/jama.291.4.470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Criscione LG, Sugarman J, Sanders L, Pisetsky DS, St Clair EW. Informed consent in a clinical trial of a novel treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003. June 15;49(3):361–7. 10.1002/art.11057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kupst MJ, Patenaude AF, Walco GA, Sterling C. Clinical trials in pediatric cancer: parental perspectives on informed consent. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2003. October;25(10):787–90. 10.1097/00043426-200310000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pope JE, Tingey DP, Arnold JM, Hong P, Ouimet JM, Krizova A. Are subjects satisfied with the informed consent process? A survey of research participants. J Rheumatol. 2003. April;30(4):815–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schats R, Brilstra EH, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, Van Gijn J. Informed consent in trials for neurological emergencies: the example of subarachnoid haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003. July;74(7):988–91. 10.1136/jnnp.74.7.988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Simon C, Zyzanski SJ, Eder M, Raiz P, Kodish ED, Siminoff LA. Groups potentially at risk for making poorly informed decisions about entry into clinical trials for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003. June 1;21(11):2173–8. 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joffe S, Cook EF, Cleary PD, Clark JW, Weeks JC. Quality of informed consent in cancer clinical trials: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2001. November 24;358(9295):1772–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06805-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Daugherty C, Ratain MJ, Grochowski E, Stocking C, Kodish E, Mick R, et al. Perceptions of cancer patients and their physicians involved in phase I trials. J Clin Oncol. 1995. May;13(5):1062–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Daugherty CK, Banik DM, Janish L, Ratain MJ. Quantitative analysis of ethical issues in phase I trials: a survey interview of 144 advanced cancer patients. IRB. 2000. May-Jun;22(3):6–14. 10.2307/3564113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hietanen P, Aro AR, Holli K, Absetz P. Information and communication in the context of a clinical trial. Eur J Cancer. 2000. October;36(16):2096–104. 10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00191-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montgomery JE, Sneyd JR. Consent to clinical trials in anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1998. March;53(3):227–30. 10.1046/j.1365-2044.1998.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Stuijvenberg M, Suur MH, de Vos S, Tjiang GC, Steyerberg EW, Derksen-Lubsen G, et al. Informed consent, parental awareness, and reasons for participating in a randomised controlled study. Arch Dis Child. 1998. August;79(2):120–5. 10.1136/adc.79.2.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Harrison K, Vlahov D, Jones K, Charron K, Clements ML. Medical eligibility, comprehension of the consent process, and retention of injection drug users recruited for an HIV vaccine trial. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995. November 1;10(3):386–90. 10.1097/00042560-199511000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harth SC, Thong YH. Parental perceptions and attitudes about informed consent in clinical research involving children. Soc Sci Med. 1995. June;40(11):1573–7. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00412-M [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Estey A, Wilkin G, Dossetor J. Are research subjects able to retain the information they are given during the consent process. Health Law Rev. 1994;3:37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Howard JM, DeMets D. How informed is informed consent? The BHAT experience. Control Clin Trials. 1981. December;2(4):287–303. 10.1016/0197-2456(81)90019-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Griffin JM, Struve JK, Collins D, Liu A, Nelson DB, Bloomfield HE. Long term clinical trials: how much information do participants retain from the informed consent process? Contemp Clin Trials. 2006. October;27(5):441–8. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guarino P, Lamping DL, Elbourne D, Carpenter J, Peduzzi P. A brief measure of perceived understanding of informed consent in a clinical trial was validated. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006. June;59(6):608–14. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barrett R. Quality of informed consent: measuring understanding among participants in oncology clinical trials. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005. July;32(4):751–5. 10.1188/05.ONF.751-755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sugarman J, Lavori PW, Boeger M, Cain C, Edsond R, Morrison V, et al. Evaluating the quality of informed consent. Clin Trials. 2005;2(1):34–41. 10.1191/1740774505cn066oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simon CM, Siminoff LA, Kodish ED, Burant C. Comparison of the informed consent process for randomized clinical trials in pediatric and adult oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2004. July 1;22(13):2708–17. 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pentz RD, Flamm AL, Sugarman J, Cohen MZ, Daniel Ayers G, Herbst RS, et al. Study of the media’s potential influence on prospective research participants’ understanding of and motivations for participation in a high-profile phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2002. September 15;20(18):3785–91. 10.1200/JCO.2002.04.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cohen L, de Moor C, Amato RJ. The association between treatment-specific optimism and depressive symptomatology in patients enrolled in a phase I cancer clinical trial. Cancer. 2001. May 15;91(10):1949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fortney JA. Assessing recall and understanding of informed consent in a contraceptive clinical trial. Stud Fam Plann. 1999. December;30(4):339–46. 10.1111/j.1728-4465.1999.t01-5-.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hutchison C. Phase I trials in cancer patients: participants’ perceptions. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 1998. March;7(1):15–22. 10.1046/j.1365-2354.1998.00062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Négrier S, Lanier-Demma F, Lacroix-Kante V, Chauvin F, Saltel P, Mercatello A, et al. Evaluation of the informed consent procedure in cancer patients candidate to immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 1995. September;31A(10):1650–2. 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00329-H [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tankanow RM, Sweet BV, Weiskopf JA. Patients’ perceived understanding of informed consent in investigational drug studies. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992. March;49(3):633–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rodenhuis S, van den Heuvel WJ, Annyas AA, Koops HS, Sleijfer DT, Mulder NH. Patient motivation and informed consent in a phase I study of an anticancer agent. Eur J Cancer Clin Oncol. 1984. April;20(4):457–62. 10.1016/0277-5379(84)90229-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Penman DT, Holland JC, Bahna GF, Morrow G, Schmale AH, Derogatis LR, et al. Informed consent for investigational chemotherapy: patients’ and physicians’ perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 1984. July;2(7):849–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Goodman NW, Cooper GM, Malins AF, Prys-Roberts C. The validity of informed consent in a clinical study. Anaesthesia. 1984. September;39(9):911–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1984.tb06582.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Riecken HW, Ravich R. Informed consent to biomedical research in Veterans Administration Hospitals. JAMA. 1982. July 16;248(3):344–8. 10.1001/jama.1982.03330030050025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bergler JH, Pennington AC, Metcalfe M, Freis ED. Informed consent: how much does the patient understand? Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980. April;27(4):435–40. 10.1038/clpt.1980.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ritsuko A, Noda K, Etsuko S, Etsuko M, Tomoko S, Midori N, et al. [Survey of participants to clinical trial in Fukuoka university hospital: relationship between the participant's understanding of informed consent and their feeling of unease for clinical trials]. Fukuoka Daigaku Igaku Kiyō. 2006;33(1):25–9. Japanese. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Paediatric European Network for Treatment of AIDS. Parents’ attitudes to their HIV-infected children being enrolled into a placebo-controlled trial: the PENTA 1 trial. HIV Med. 1999. October;1(1):25–31. 10.1046/j.1468-1293.1999.00005.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ballard HO, Shook LA, Desai NS, Anand KJ. Neonatal research and the validity of informed consent obtained in the perinatal period. J Perinatol. 2004. July;24(7):409–15. 10.1038/sj.jp.7211142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bertoli AM, Strusberg I, Fierro GA, Ramos M, Strusberg AM. Lack of correlation between satisfaction and knowledge in clinical trials participants: a pilot study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2007. November;28(6):730–6. 10.1016/j.cct.2007.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Burgess E, Singhal N, Amin H, McMillan DD, Devrome H. Consent for clinical research in the neonatal intensive care unit: a retrospective survey and a prospective study. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2003. July;88(4):F280–5, discussion F285–6. 10.1136/fn.88.4.F280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chaisson LH, Kass NE, Chengeta B, Mathebula U, Samandari T. Repeated assessments of informed consent comprehension among HIV-infected participants of a three-year clinical trial in Botswana. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e22696. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chappuy H, Baruchel A, Leverger G, Oudot C, Brethon B, Haouy S, et al. Parental comprehension and satisfaction in informed consent in paediatric clinical trials: a prospective study on childhood leukaemia. Arch Dis Child. 2010. October;95(10):800–4. 10.1136/adc.2009.180695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]