Abstract

BACKGROUND

Although the use of SSM is becoming more common, there are few data on long-term, local-regional, and distant recurrence rates after treatment. The purpose of this study was to examine the rates of local, regional, and systemic recurrence, and survival in breast cancer patients who underwent skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) or conventional mastectomy (CM) at our institution.

METHODS

Patients with stage 0 to III unilateral breast cancer who underwent total mastectomy at our center from 2000 to 2005 were included in this study. Kaplan-Meier curves were calculated, and the log-rank test was used to evaluate the differences between overall and disease-free survival rates in the 2 groups.

RESULTS

Of 1810 patients, 799 (44.1%) underwent SSM and 1011 (55.9%) underwent CM. Patients who underwent CM were older (58.3 vs 49.3 years, P<.0001) and were more likely to have stage IIB or III disease (53.0% vs 31.8%, P<.0001). Significantly more patients in the CM group received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and adjuvant radiation therapy (P<.0001). At a median follow-up of 53 months, 119 patients (6.6%) had local, regional, or systemic recurrences. The local, regional, and systemic recurrence rates did not differ significantly between the SSM and CM groups. After adjusting for clinical TNM stage and age, disease-free survival rates between the SSM and CM groups did not differ significantly.

CONCLUSIONS

SSM is an acceptable treatment option for patients who are candidates for immediate breast reconstruction. Local-regional recurrence rates are similar to those of patients undergoing CM.

Keywords: local and regional recurrence rates, systemic recurrence rate, skin-sparing mastectomy, breast cancer, conventional mastectomy

The popularity of skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) for the surgical treatment of early-stage breast cancer has risen over the past decade. This technique was first described by Freeman in 19621 and modified by Toth and Lappert in 1991.2 SSM consists of a total mastectomy with resection of the nipple-areola complex, while preserving as much of the native skin envelope as possible.

By preserving the inframammary fold and native skin envelope, skin-sparing mastectomy (SSM) greatly enhances the aesthetic results of immediate breast reconstruction. However, because less skin is resected in SSM compared with conventional mastectomy (CM), concerns persist that SSM might increase the risk of local, regional, or systemic recurrence of breast cancer. A limited number of studies have examined this question and have not shown an increase in local recurrences associated with SSM.3-10 However, many of these were small case series, were limited by short follow-up times, involved heterogeneous patient groups with various stages of breast cancer, or lacked control groups.

The aim of this study was to examine the rates of local, regional, and systemic recurrence, and survival in breast cancer patients who underwent SSM, and to compare these rates with those of breast cancer patients who underwent CM at our institution.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Selection and Data Collection

The use of immediate breast reconstruction has been combined with SSM at our institution since March 1986. This practice was initially limited to highly selected patients, but, over the past decade, has been expanded to include most patients with ductal carcinoma in situ and those individuals with T1 and T2 tumors who elect or require mastectomy and desire reconstruction. The clinical and pathologic criteria used for selecting patients for SSM at our institution include patients with ductal carcinoma in situ who are planned for immediate breast reconstruction; patients with early stage invasive disease who are felt to be at low risk for requiring postmastectomy radiation therapy and are planned for immediate breast reconstruction; and patients with locally advanced disease who have received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and are candidates for tissue expander-based reconstruction that can be deflated for the purposes of postmastectomy radiation therapy delivery. Patients are evaluated by the Surgical Breast Oncology Service and the Plastic Surgery Service preoperatively to determine their suitability for skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Those patients who are planned for postmastectomy radiation therapy and those considered to be at increased risk for requiring postmastectomy radiation therapy on the basis of primary tumor factors are evaluated preoperatively by Radiation Oncology. Important considerations are whether a tissue expander-based reconstruction would interfere with delivery of postmastectomy and/or regional nodal irradiation, and whether the patient has autologous tissue donor sites that can be used for definitive reconstruction at the completion of the radiation. Patients with inflammatory breast cancer are not considered candidates for skin-sparing mastectomy.

We used the Surgical Breast Oncology Database at The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center to identify patients with stage 0 to III primary breast carcinoma who underwent total mastectomy with or without complete axillary dissection from January 2000 through December 2005. We excluded patients with bilateral breast cancer, those who underwent mastectomy for recurrent breast cancer, and those with less than 2 years of follow-up; the remaining 1810 patients were included in the study. The M. D. Anderson Institutional Review Board approved this study.

For each patient, we extracted demographic, pathologic, clinical, and follow-up data from the database. Demographic data included age and race. Pathologic data included nuclear grade, histology, lymph node status, lymphovascular invasion, final margin status, estrogen receptor (ER) status, progesterone receptor (PR) status, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) status. Clinical data included clinical stage, use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, use of adjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant hormonal therapy, and adjuvant radiation therapy. Finally, follow-up data included evaluation of the occurrence and timing of local, regional, and systemic recurrence, as well as vital status at last follow-up.

Surgery

Mastectomies were performed with or without sentinel lymph node dissection or axillary lymph node dissection as considered appropriate, in light of the diagnostic biopsy findings and clinical staging. SSM was performed by breast surgeons to encompass resection of the nipple-areola complex with the entire breast parenchyma, including biopsy scars and/or skin overlying superficial tumors. Excisional biopsy scars for cancer diagnosis were excised when feasible. Skin incisions from percutaneous core biopsy procedures were not routinely excised. Excisional biopsy scars from previous benign biopsies were left intact. Various incisions were used for the SSM (Fig. 1) per the surgeon’s preference and planned reconstructive approach. Table 1 details the advantages and disadvantages of the various incisions. When sentinel lymph node (SLN) dissection or axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) was performed, most surgeons used a second axillary incision for access to the regional nodes. SSM was typically followed by immediate breast reconstruction, performed by a team of reconstructive surgeons in a single operative procedure. The reconstruction method was determined by the patient’s anatomy and preferences. In some cases, a 2-stage reconstructive approach was used with insertion of a tissue expander as the initial surgery, followed by a permanent implant, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap, or latissimus dorsi flap at a second surgery.

Figure 1.

Choices for skin-sparing mastectomy incisions.(Left) Mastectomy incisions for patients not requiring a mastopexy: Periareolar Incision Only (white circle). The lack of disruption of the circumferential blood supply to the breast skin envelope because of the lack of incision on the breast preserves the circumferential subdermal vascular perfusion. Racquet Handle Incision (white circle plus black line). The lateral breast incision disrupts the circumferential circulation to the remaining breast skin envelope. Periareolar Plus Counter Axillary Incision (white circle plus red and dashed blue line). Extension of axillary incision anteriorly may limit the width of skin-bridge between itself and the periareolar incision that may adversely affect the circumferential vascular perfusion. This may be problematic in patients with a small breast with a large areola, in which the width between the 2 incisions is already narrow. Periareolar Plus Axillary Sentinel Lymph Node Incision (white circle plus red line). Circumferential perfusion is maintained in the subdermal plexus of the breast skin envelope, decreasing the potential for breast skin flap necrosis. The separate axillary sentinel node biopsy incision avoids having to extensively undermine the lateral breast skin flap to access the involved lymph node(s) that may affect perfusion to the breast skin.(Right) Mastectomy incisions for patients requiring a mastopexy. Wise Skin Pattern (dashed black line) incision is not preferred because of the high rate of breast skin flap necrosis that is upwards of 50%. The lateral skin flap is at most risk because of the extensive lateral undermining that is often associated with mastectomy and axillary surgery. Concentric Mastopexy (white oval) incision is preferred because it maintains the circumferential circulation to the breast skin envelope without disruption from associated incisions on the breast. Skin closure results in a short transverse incision that can be camouflaged after reconstruction of the nipple and areola reduction.

Table 1.

Types of Mastectomy Incisions Utilized in Skin-Sparing Mastectomy

| Type of Mastectomy Incision | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Racquet handle incision |

|

|

| Periareolar incision only |

|

|

| Periareolar plus counter axillary incision |

|

|

| Periareolar plus axillary SLN biopsy incision |

|

|

SLN indicates sentinel lymph nodes.

Classification of Recurrence

Routine follow-up consisted of history taking and a physical examination that included the breast, chest wall, and regional nodal basins at 3- or 6-month intervals for 5 years, combined with annual mammography of the contralateral breast. Other imaging studies were performed only when indicated by symptoms or physical examination findings.

First sites of recurrence were classified as local, regional, or systemic. Isolated skin, chest wall, and/or subcutaneous recurrences were considered local, and isolated regional lymph node metastases were classified as regional.

Data Analysis

Patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics were evaluated and compared between the SSM and CM groups. The Wilcoxon rank sum test or the Student t test was used to compare the means of continuous variables. The chi-square test or Fisher exact test was used for univariate comparison of categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were calculated for the 2 groups, and the log-rank test was used to compare overall and disease-free survival between groups. The stratified log-rank test was used for equality of survivor functions between SSM and CM, stratified by clinical TNM stage. A multivariate stratified Cox proportional hazards model was used to identify significant predictors of disease-free survival, stratifying by clinical TNM stage and age. Estimated risks of death were calculated using hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Stata statistical software (SE 9, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) was used for statistical analyses. All P values were 2-tailed, and P ≤ .05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

We identified a total of 1810 patients who underwent total or modified radical mastectomy at our institution from January 2000 through December 2005. Of these, 799 patients (44.1%) underwent SSM and 1011 (55.9%) underwent CM.

The patient and tumor characteristics of the 2 groups are summarized in Table 2. Patients who underwent CM had a higher mean age and higher proportion of stage IIB or III disease than did those who underwent SSM. African American patients were more likely to undergo CM than SSM. A higher percentage of patients in the CM group had invasive tumors than did patients in the SSM group. No significant differences were noted in histologic grade, final margin status, ER status, HER-2 receptor status, presence of lymphovascular invasion, or other clinicopathologic factors between the SSM and CM groups.

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic Characteristics

| Characteristic | CM n=1011 (%) |

SSM n=799 (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | <.0001a | ||

| Mean | 58.3 | 49.3 | |

| Median (range) | 58 (21-89) | 49 (22-79) | |

| Race | .036 | ||

| White | 724 (71.6) | 614 (76.9) | |

| Black | 183 (18.1) | 113 (14.1) | |

| Other | 104 (10.3) | 72 (9.0) | |

| Clinical stage | <.0001 | ||

| 0 | 135 (13.4) | 235 (29.4) | |

| I | 340 (33.6) | 311 (38.9) | |

| II | 424 (41.9) | 221 (27.7) | |

| III | 112 (11.1) | 32 (4.0) | |

| Clinical stage | <.0001 | ||

| 0, I, IIA | 475 (47.0) | 545 (68.2) | |

| IIB or higher | 536 (53.0) | 254 (31.8) | |

| Invasive tumor | <.0001 | ||

| No | 83 (8.2) | 143 (17.9) | |

| Yes | 928 (91.8) | 656 (82.1) | |

| Positive lymph node | <.0001 | ||

| No | 763 (75.5) | 669 (83.7) | |

| Yes | 248 (24.5) | 130 (16.3) | |

| Modified Black’s nuclear grade | .15b | ||

| 1 | 91 (9.0) | 55 (6.9) | |

| 2 | 474 (46.9) | 370 (46.3) | |

| 3 | 397 (39.3) | 341 (42.7) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | .24b | ||

| No | 580 (57.4) | 477 (59.7) | |

| Yes | 156 (15.4) | 109 (13.6) | |

| Final margin | .85 | ||

| Positive | 3 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Negative | 1008 (99.7) | 797 (99.7) | |

| Estrogen receptor status | .99b | ||

| Positive | 700 (69.2) | 526 (65.8) | |

| Negative | 202 (20.0) | 152 (19.0) | |

| Progesterone receptor status | .009b | ||

| Positive | 544 (53.8) | 433 (54.2) | |

| Negative | 352 (34.8) | 241 (30.2) | |

| HER-2 status | .16b | ||

| Positive | 166 (16.4) | 130 (16.3) | |

| Negative | 672 (66.5) | 436 (54.6) |

CM indicates conventional mastectomy; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy; LN, lymph node; HER-2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2.

By Wilcoxon rank sum test.

P value calculated after exclusion of the unknown category.

Surgical Treatment

In the CM group, 18.1% of the patients underwent modified radical mastectomy with SLN surgery, 50.9% had a total mastectomy with SLN surgery, 23.9% underwent modified radical mastectomy without SLN surgery, and 7.1% had a total mastectomy without nodal surgery. In the SSM group, 28.3% underwent modified radical mastectomy and 71.7% underwent total mastectomy (Table 3). A higher percentage of patients in the SSM group underwent SLN surgery for nodal staging (76.1%) than in the CM group (69%, P = .001).

Table 3.

Surgical Treatment of Primary Tumor

| Characteristic | CM n=1011 (%) |

SSM n=799 (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of mastectomy | <.0001 | ||

| Total | 586 (58.0) | 573 (71.7) | |

| Modified radical | 425 (42.0) | 226 (28.3) | |

| SLN biopsy | .001 | ||

| No | 313 (31.0) | 191 (23.9) | |

| Yes | 689 (68.2) | 608 (76.1) | |

| BR (immediate or delayed) | <.0001 | ||

| Yes | 171 (16.9) | 790 (98.9) | |

| No | 840 (83.1) | 9 (1.1) | |

| BR type (% of BR) | |||

| Tissue expander | 77 (45.0) | 324 (42.1) | |

| TRAM | 68 (39.8) | 360 (46.8) | |

| LD | 10 (5.8) | 56 (7.3) | |

| Others | 16 (9.4) | 29 (3.8) |

CM indicates conventional mastectomy; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy; SLN, sentinel lymph node; BR, breast reconstruction; TRAM, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap; LD, latissimus dorsi flap.

Immediate breast reconstruction was performed in 98.1% of patients who underwent SSM and 16.9% of the patients who underwent CM. Delayed breast reconstruction was performed in 1.9% of patients who underwent SSM. In both groups, transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous flap and 2-stage breast implant reconstruction (with insertion of a tissue expander followed by a permanent breast implant) were the 2 most common techniques used for immediate breast reconstruction (Table 3).

Systemic Treatments and Radiation Therapy

Preoperative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy was administered in 20.5% of the SSM patients and 29.6% of the CM patients (P < .0001). Postoperative (adjuvant) chemotherapy was administered in 62.3% of the SSM patients and 63.1% of the CM patients (P = .7). Adjuvant hormonal therapy was given to 59.2% of SSM patients and 62.4% of CM patients. Postoperative radiation therapy was delivered to 11.6% of the SSM patients and 25.1% of the CM patients (P < .0001). Table 4 summarizes the use of systemic and radiation therapies.

Table 4.

Neoadjuvant and Adjuvant Therapy

| Characteristic | CM n=1011 (%) |

SSM n=799 (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | <.0001 | ||

| No | 712 (70.4) | 635 (79.5) | |

| Yes | 299 (29.6) | 164 (20.5) | |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy | <.0001 | ||

| Yes | 254 (25.1) | 93 (11.6) | |

| No | 757 (74.9) | 706 (88.4) | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | .73 | ||

| Yes | 373 (36.9) | 301 (37.7) | |

| No | 638 (63.1) | 498 (62.3) | |

| Adjuvant hormonal therapy | .16 | ||

| Yes | 631 (62.4) | 473 (59.2) | |

| No | 380 (37.6) | 326 (40.8) |

CM indicates conventional mastectomy; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy.

Recurrence Rates

Patients who underwent SSM had a median follow-up time of 53 months (range, 24-101), as did those who underwent CM (range, 24-104; P = .07). The median time to first recurrence in the CM group was 28.7 months (range, 0.5-95.3) and in the SSM group 32.1 months (range, 1.1-86.3; P = 0.6).

The overall recurrence rate was 5.3% (42 of 799 patients) for SSM patients and 7.6% (77 of 1011 patients) for CM patients (P = .04, Table 5). Of the 42 patients in the SSM group who had recurrences, 9.5% (4 patients) had local or regional recurrences only, 64.3% (27 patients) had systemic recurrences only, and 26.2% (11 patients) had both local-regional and systemic recurrences. Of the 77 patients in the CM group who had recurrences, 9.1% (7 patients) had local or regional recurrences only, 71.4% (55 patients) had systemic recurrences only, and 19% (15 patients) had both local-regional and systemic recurrences. The local and systemic recurrence rates were lower in the SSM group compared with the CM group.

Table 5.

Recurrence Patterns

| Characteristic | CM n=1011 (%) |

SSM n=799 (%) |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any recurrence | .04 | ||

| No | 934 (92.4) | 755 (94.5) | |

| Yes | 77 (7.6) | 42 (5.3) | |

| Local recurrence | .11 | ||

| No | 997 (98.6) | 794 (99.4) | |

| Yes | 14 (1.4) | 5 (0.6) | |

| Regional recurrence | .70 | ||

| No | 998 (98.7) | 787 (98.5) | |

| Yes | 13 (1.3) | 12 (1.5) | |

| Systemic recurrence | .05 | ||

| No | 941 (93.1) | 761 (95.2) | |

| Yes | 70 (6.9) | 38 (4.8) |

CM, conventional mastectomy; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy.

Among patients with stage 0 cancer, there were 3 recurrences in the SSM group and 2 in the CM group, all of which were systemic. In patients with stage I disease, there were 14 total recurrences in the SSM group (1 local, 13 systemic) and 14 in the CM group (all systemic). In patients with stage II disease, there were 21 recurrences in the SSM group (3 local, 18 systemic) and 41 in the CM group (11 local, 30 systemic). In patients with stage III disease, there were 4 recurrences in the SSM group (1 local, 3 systemic) and 20 in the CM group (3 local, 17 systemic). The local recurrence rates in patients with invasive tumors (stage I to III) were 0.8% and 1.5% for the SSM and CM groups, respectively. Local recurrence rates increased with stage, from 0.32% for patients with stage I disease to 1.36% for patients with stage II disease and 3.31% for those with stage III disease. The local recurrence rates for patients with stage IIB or higher disease were 1.6% in the SSM group and 2.6% in the CM group (P = .4).

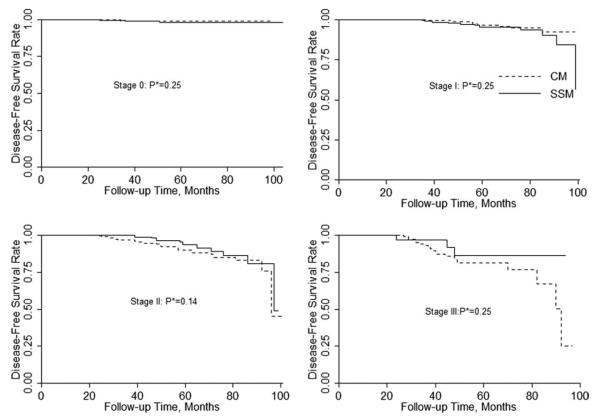

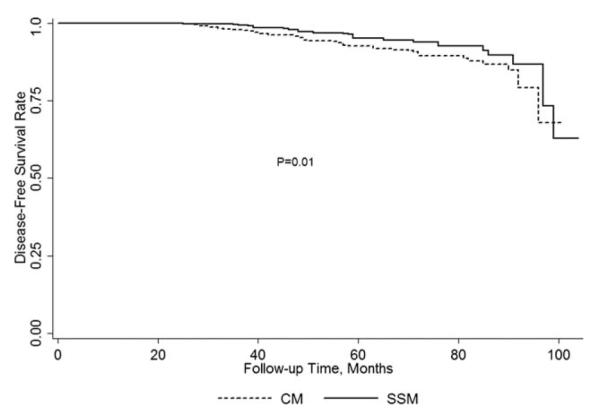

Survival

The 5-year actuarial disease-free survival rate was 95.2% for patients who underwent SSM and 92.7% for patients who underwent CM (P = .01, Fig. 2). For patients with local-regional recurrences, the 5-year actuarial disease-free survival rate was 97.7% in the SSM group and 97.5% in the CM group (P = .58). For patients with distant recurrences, the 5-year actuarial disease-free survival rate was 94.7% in the SSM group and 93.1% in the CM group (P = .03). At a median follow-up time of 53 months, there were no significant differences in disease-free survival rates between the SSM and CM groups after adjusting for clinical TNM stage (Fig. 3). Table 6 shows the clinical and pathological factors affecting disease-free survival stratified by clinical TNM stage and age. Patients who had local-regional recurrence, negative ER status, or had positive lymph nodes found during surgery had shorter disease-free survival. The use of SSM did not affect disease-free survival.

Figure 2.

Unadjusted disease-free survival rates in patients who underwent SSM vs CM.

Figure 3.

Clinical TNM stage adjusted disease-free survival rates in patients undergoing SSM and CM (*P values were calculated by stratified log-rank test).

Table 6.

Multivariate Stratified Cox Proportional Hazards Model of Breast Cancer Disease-Specific Survival

| HRa | P a | 95% CIa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local-Regional recurrence | |||

| No | Referent | ||

| Yes | 10.2 | <.0001 | 4.1-25.3 |

| Surgery type | |||

| CM | Referent | ||

| SSM | 0.6 | .1 | 0.3-1.2 |

| Estrogen receptor status | |||

| Positive | Referent | ||

| Negative | 4.0 | <.0001 | 2.1-7.8 |

| Positive lymph node | |||

| No | Referent | ||

| Yes | 2.4 | .007 | 1.3-4.4 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; CM, conventional mastectomy; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy.

Stratified by clinical TNM stage and age.

Treatment of Local Recurrences

All local recurrences were treated by wide local excision followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy (when deemed appropriate by the treating physicians). Negative margins were obtained in all cases of salvage surgery, and none of the reconstructed breasts had to be surgically removed. During follow-up, none of these patients developed new local, regional, or systemic recurrences.

DISCUSSION

Concerns about oncologic safety and the poorly defined clinical indications for SSM have slowed the incorporation of this technique into clinical practice.11,12 Skin preservation, which improves the aesthetic outcome of immediate breast reconstruction, has gained a foothold in the treatment of patients with noninvasive and stage I breast cancer, but concerns about the risk of local recurrence have limited its use in patients with stage II and stage III disease. In our study, we found no significant differences in local, regional, or systemic recurrence rates between patients who underwent SSM and patients who underwent CM. And there were no significant differences in local or systemic recurrence patterns between the SSM and CM groups when controlled for stage. Among patients with stage 0 tumors, no local recurrences occurred at a median follow-up time of 53 months.

Prospective data comparing the rates of local and regional recurrences after SSM and CM are not available. Several retrospective reviews have reported similar recurrence rates for patients undergoing SSM (2.9% to 6.7%) and CM (3.0% to 9.5%), with median follow-up times ranging from 41 to 72 months.2,4,7,9,13,14 A recent meta-analysis of 9 observational studies comparing SSM versus non-SSM for breast cancer reported that SSM was not significantly different from non-SSM in terms of rates of local recurrence.15 Unfortunately, adjuvant treatment data are incomplete or absent in many of these studies. Most of the initial studies of SSM included only patients with in situ or early-stage invasive disease. These studies had local recurrence rates ranging from 1.7% to 7.0%, with mean follow-up times of 49 to 118 months.6-9,16 These studies included patients treated from 1985 to 1994, early in the experience of most surgeons performing SSM. More recently, SSM has been used in the treatment of patients with larger primary tumors and some patients with locally advanced breast cancer,3,5,10,14,17 with local recurrence rates ranging from 9.9% to 11.1% for patients with T2 to T4 cancers.3,14 In our study, 31.8% of patients treated with SSM had stage IIB or higher disease, and local recurrence rates increased with stage, from 0.32% for stage I to 3.31% for stage III. Nevertheless, the rates of local recurrence in patients with locally advanced disease undergoing SSM and CM were similar. Although the sequencing of treatments and delivery of radiation therapy can be challenging with SSM and immediate breast reconstruction, our data and previous studies suggest that the use of SSM is oncologically safe in patients with stage II and selected patients with stage III disease.14,18

The local recurrence rate of 0.6% in our series is much lower than the results of other studies (Table 7). This may be ascribed to the significant use of adjuvant systemic therapies in this patient population. Meretoja et al recently reported a study of 146 patients who underwent SSM from 1992 to 2006. They noted that 2.7% of patients suffered a local recurrence at a mean follow-up of 51 months.8 Another contemporary series by Garwood et al evaluated 106 SSM patients from 2005 to 2007 at a mean follow-up of 13 months, noting that only 0.6% of patients had local recurrence. Comparisons of these results are not straightforward, as many of these studies include patients treated before 2000, and some include only patients with stage I and II disease. Also, the guidelines for using adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation therapy differ between hospitals and countries. Differences in the use of radiation therapy after mastectomy may also impact the local recurrence rates in different studies, as radiation therapy has been shown to substantially reduce local recurrences independent of primary tumor characteristics. As shown in Table 7, local recurrence rates have trended downward in recent years.5,6,8 These lower local recurrence rates may be a result of the increased use of systemic therapies (chemotherapy and hormonal therapy), in addition to improvements in imaging and pathologic techniques. SSM and CM appear to be equally effective at preventing local recurrence, although the influence of case selection on reported outcomes is unclear.

Table 7.

LR Rates After SSM and IBR in Published Studies With More Than 100 Patients

| First Author | Year | Years Covered |

No. of Patients |

Stages | Mean Follow-up, Mo |

LR Rate, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newman9 | 1998 | 1986-1993 | 372 | I-II | 50 | 6.2 |

| Kroll7 | 1999 | 1986-1990 | 114 | I-II | 72 | 7.0 |

| Medina-Franco14 | 2002 | 1986-1997 | 173 | I-III | 73 | 4.5 |

| Spiegel10 | 2003 | 1985-1994 | 221 | 0-IV | 118 | 4.5 |

| Carlson3 | 2003 | 1989-1998 | 565 | 0-IV | 65 | 5.5 |

| Greenway6 | 2005 | 1989-2004 | 225 | 0-II | 49 | 1.7 |

| Meretoja8 | 2007 | 1992-2006 | 146 | I-II | 51 | 2.7 |

| Vaughan17 | 2007 | 1998-2006 | 210 | 0-IV | 58.6 | 5.3 |

| Carlson16 | 2007 | 1991-2003 | 223 | 0 | 82.3 | 5.1 |

| Garwood5 | 2009 | 2005-2007 | 106 | 0-III | 13 | 0.6 |

| Yi | Present study | 2000-2005 | 546 | 0-IIA | 55.5 | 0.2 |

| Yi | Present study | 2000-2005 | 253 | IIB or III | 54.8 | 1.6 |

LR indicates local recurrence; SSM, skin-sparing mastectomy; IBR, immediate breast reconstruction.

In our study, the patients in the SSM group were younger (mean, 49 years) than those in the CM group. Other studies have found that patients undergoing SSM tend to be younger, with a mean age of 41 years.9,19 This may represent a selection bias on the part of surgeons, with young patients being offered SSM more often, or, perhaps, a predilection for young patients to seek SSM with immediate reconstruction.

Because of the smaller incision and more difficult exposure, the SSM procedure is technically more challenging than that of CM. SSM requires motivation by the oncologic surgeon to invest the additional time and effort required over that of performing a CM. It has been questioned whether SSM has a higher rate of complications than CM. Although complications were not evaluated in this study, other studies have shown that complications such as native skin flap necrosis occurred in 10.7% of patients who underwent SSM and in 11.2% of patients who underwent CM (P = not significant).20,21 If a patient is deemed a candidate for breast reconstruction, the skin-sparing procedure should not incur additional risks.

Because the recurrence rates in our study were low, we could not evaluate predictors of recurrence. Such an analysis would require a very large population of patients with long follow-up periods, perhaps from multiple institutions. Because prospective randomized studies to compare SSM and CM would be difficult, case-control studies might be needed, with control populations carefully chosen to match age, tumor size, stage, reconstruction type, and follow-up time.

In conclusion, our study showed that SSM does not pose a higher risk of local, regional, or systemic recurrences over conventional mastectomy. Although universal adoption of SSM has not yet occurred, the procedure is oncologically safe and provides a superior cosmetic outcome.22 Skin-sparing mastectomy should therefore be considered standard of care for the patients undergoing mastectomy when immediate reconstruction is used.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING STATEMENT: This article was supported by NIH. The grant number is P30 CA016672.

We are grateful to Cynthia Guerrero, B.A. and Khazi Nayeemuddin, M.D. for their assistance with data collection and Bryan F. Tutt for editorial assistance.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES The authors made no disclosures.

Presented in part at the 31st Annual San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium, December 14-17, 2008, San Antonio, Texas

REFERENCES

- 1.Freeman BS. Subcutaneous mastectomy for benign breast lesions with immediate or delayed prosthetic replacement. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1962;30:676–682. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toth BA, Lappert P. Modified skin incisions for mastectomy: the need for plastic surgical input in preoperative planning. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87:1048–1053. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlson GW, Styblo TM, Lyles RH, et al. The use of skin sparing mastectomy in the treatment of breast cancer: The Emory experience. Surg Oncol. 2003;12:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foster RD, Esserman LJ, Anthony JP, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective cohort study for the treatment of advanced stages of breast carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:462–466. doi: 10.1007/BF02557269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garwood ER, Moore D, Ewing C, et al. Total skin-sparing mastectomy: complications and local recurrence rates in 2 cohorts of patients. Ann Surg. 2009;249:26–32. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e41a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenway RM, Schlossberg L, Dooley WC. Fifteen-year series of skin -sparing mastectomy for stage 0 to 2 breast cancer. Am J Surg. 2005;190:918–922. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kroll SS, Khoo A, Singletary SE, et al. Local recurrence risk after skin-sparing and conventional mastectomy: a 6-year follow-up. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104:421–425. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199908000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meretoja TJ, von Smitten KA, Leidenius MH, et al. Local recurrence of stage 1 and 2 breast cancer after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction in a 15 - year series. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:1142–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman LA, Kuerer HM, Hunt KK, et al. Presentation, treatment, and outcome of local recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 1998;5:620–626. doi: 10.1007/BF02303832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spiegel AJ, Butler CE. Recurrence following treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ with skin -sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:706–711. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000041440.12442.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bleicher RJ, Hansen NM, Giuliano AE. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Specialty bias and worldwide lack of consensus. Cancer. 2003;98:2316–2321. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sotheran WJ, Rainsbury RM. Skin-sparing mastectomy in the UK—a review of current practice. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004;86:82–86. doi: 10.1308/003588404322827437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlson GW, Bostwick J, 3rd, Styblo TM, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy. Oncologic and reconstructive considerations. Ann Surg. 1997;225:570–575. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199705000-00013. discussion 575-578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina-Franco H, Vasconez LO, Fix RJ, et al. Factors associated with local recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction for invasive breast cancer. Ann Surg. 2002;235:814–819. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lanitis S, Tekkis PP, Sgourakis G, et al. Comparison of skin-sparing mastectomy versus non-skin-sparing mastectomy for breast cancer: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Surg. 2010;251:632–639. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d35bf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson GW, Page A, Johnson E, et al. Local recurrence of ductal carcinoma in situ after skin-sparing mastectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:1074–1078. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.01.063. discussion 1078-1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaughan A, Dietz JR, Aft R, et al. Scientific Presentation Award. Patterns of local breast cancer recurrence after skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction. Am J Surg. 2007;194:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downes KJ, Glatt BS, Kanchwala SK, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction is an acceptable treatment option for patients with high-risk breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;103:906–913. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons RM, Fish SK, Gayle L, et al. Local and distant recurrence rates in skin -sparing mastectomies compared with non-skin-sparing mastectomies. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6:676–681. doi: 10.1007/s10434-999-0676-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipshy KA, Neifeld JP, Boyle RM, et al. Complications of mastectomy and their relationship to biopsy technique. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3:290–294. doi: 10.1007/BF02306285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinton AL, Traverso LW, Jolly PC. Wound complications after modified radical mastectomy compared with tylectomy with axillary lymph node dissection. Am J Surg. 1991;161:584–588. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(91)90905-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen J, Ellenhorn J, Qian D, et al. Skin-sparing mastectomy: a survey based approach to defining standard of care. Am Surg. 2008;74:902–905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]