Worldwide, there are approximately 13 million refugees and asylum seekers.1 Flight of refugees often occurs in the setting of war, famine, or human rights violations, resulting from a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.”2 Physicians in host countries increasingly encounter refugees in their practices and, owing to inadequate training, may not fully meet their complex medical needs.

Sources and selection criteria

Limited evidence exists to support many aspects of refugee health care. When scientific evidence is not available, recommendations stem from our experience in caring for a diverse group of refugees (East African, Balkan, and South East Asian) in a multidisciplinary setting involving primary care physicians, obstetrician-gynaecologists, psychiatrists, nurses, cultural interpreters, and social workers. This article is based on clinical expertise and a review of the literature obtained from a Medline search using the key words “refugee” and “asylum seekers.” We suggest an approach to obtaining the refugee history, screening for infectious diseases and common psychiatric disorders, and dealing with special problems such as ritual female genital surgery (female circumcision).

Refugee camps and medical interventions before embarkation

Refugee camps represent the first point of escape, but continued interethnic strife, sexual violence, and disease epidemics often perpetuate the dangerous environment from which people fled. Although the United Nations High Commission for Refugees promises protection and basic medical care, refugees may actually have higher mortality in camps than in their home country. Major causes of mortality in refugee camps include diarrhoeal diseases, measles, acute respiratory tract infections, tuberculosis, and malaria. Mandated medical screening of refugees before arrival in the United States identifies those with “inadmissible conditions,” including active infections such as tuberculosis, leprosy, and HIV infection. Typical screening of adult refugees involves a physical examination, brief mental health assessment, chest radiograph (sputum testing for tuberculosis if abnormal), and testing for syphilis and HIV. Enhanced health assessments may also be done to identify prevalent diseases that may serve as future public health targets before immigration. For example, frequent diagnoses of malarial (7%) and intestinal (38%) parasites in Barawan Somali refugees led the Centers for Disease Control to recommend mass treatment for all non-pregnant refugees older than 2 years; this consisted of single oral doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine and albendazole before departure.3

Summary points

The complex medical needs of refugees are often unmet owing to inadequate training of healthcare providers

Medical problems include infectious diseases, psychiatric disorders, and complications from ritual female genital surgery

Symptoms of infectious diseases and history of exposure to trauma and ritual female genital surgery should be sought in the medical history

Routine laboratory screening for infectious diseases may detect parasites, sexually transmitted infections, hepatitis, and tuberculosis

Further information on post-traumatic stress disorder, somatisation, and ritual female genital surgery may enable physicians to care better for refugees

Medical history and physical examination

Interpreter services are essential for obtaining the medical history and caring effectively for refugees. The lack of translators, particularly for new or small groups of refugees, is an important barrier to health care. Ideally, the interpreter not only translates but also acts as a mediator to explain the cultural context of a patient's symptoms. On first meeting the refugee, we clarify the purpose of a routine visit to a physician, the role of the interpreter, and the concept of preventive screening. Eliciting sensitive information, such as exposure to trauma, may begin by asking the patient's “life story” and focusing sequentially on life in the home country, reason for flight, details of escape, and status of family members (box 1).4,5 We also do a complete review of infectious diseases by body system and inquire about use of traditional or herbal medicines. We ask African women about ritual female genital surgery, as it can have important implications for gynaecological health.

Box 1: Medical history*

Life story

-

Pre-flight:

- Country of origin and reason for escape

- Life and employment before immigration

- Medical problems or stress in home country

-

Path to host country:

- Time spent in refugee camps, location of the camps

- Physical separation from loved ones

- Losses of family members or friends and reasons for death

Infectious diseases

History of disease or exposure: tuberculosis, malaria, parasites, hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections

-

Review of systems:

- Recurrent fevers, night sweats, weight loss

- Cough, haemoptysis

- Diarrhoea, visible parasites in stool

- Jaundice

- Vaccine status: previous records and history of infections or vaccination

Traditional medicine and substance misuse

Use of herbal medicines

Acupuncture, moxibustion, coining, other modalities

Use of substances other than tobacco and alcohol

Sexual history and genital surgery

-

Reproductive history:

- Gravidity, parity, outcome of previous childbirths

- Sexual activity, desire for testing for sexually transmitted infections, contraception or pregnancy

-

Ritual female genital surgery:

- Ability to have intercourse, dyspareunia

- Chronic urinary tract infections, pelvic pain, scar abscesses

- Desire for revision of circumcision (defibulation)

Trauma history†

Deprivation of food, water, or shelter

Being lost, kidnapped, or imprisoned

Enforced isolation

Undergoing torture or serious injury

Being brainwashed

Being raped or sexually molested

Witnessing a murder or violent acts

Feeling close to death

Being in a combat situation

*Contents of the box are based on clinical expertise as guided by limited scientific evidence

†Components of the trauma history are adapted from Harvard trauma questionnaire6

After rapport and trust have been established, we directly inquire about torture, rape, or other physical or psychological trauma by using an approach adapted from the Harvard trauma questionnaire (box 1).6 Many translations of the questionnaire exist to facilitate taking the trauma history. Questions about depressive symptoms may need modification for each refugee group, and medical interpreters are helpful in this regard. For example, one direct translation of “depression” into Somali is “wal-wal,” which also means “crazy.”

A complete physical examination may reveal pathological and non-pathological conditions, including lymphadenopathy, goitre, and evidence of previous traditional medicine techniques. African and South East Asian refugees often have circular scars consistent with dermabrasion from coining or moxibustion. Signs of torture may be subtle and include occult fractures from beatings or 1-2 mm clustered scars from electrical burns.7

Routine screening

Guidelines for screening of refugees are mainly based on studies documenting a high prevalence of infectious diseases and medical disorders.8,9 Obtaining records from overseas refugee screening may prevent repetitive testing. We begin with a complete blood count with differential and infectious disease screening (box 2). Common causes of anaemia among refugees include deficiencies of iron and other nutritional factors, haemoglobinopathies, α and β thalassaemia, and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency. Eosinophilia warrants investigation for pathogenic parasites, even in mild cases. In a group of South East Asian refugees with eosinophilia and negative stool ova and parasite testing, a parasite was eventually detected in 95% of cases.10

Screening for infectious diseases includes testing for tuberculosis, intestinal parasites, hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections. Whether to give empirical treatment or to screen for parasites remains controversial. Estimates of cost effectiveness are based on a five day course of albendazole, whereas many centres administer a single dose.11 Depending on the history of sexual activity, testing should include screening for gonorrhoea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV-1 (and HIV-2 for West African refugees). In lieu of vaccination records, testing for antibodies to indicate exposure to or vaccination against disease should be done. Antibody testing is more cost effective than varicella vaccination in refugees older than 5 years.12 However, the positive predictive value of a varicella history is 93-100% and may be adequate for documentation in certain refugee groups. Additional components of screening include an oral examination, dental referral, and screening of vision and hearing.

Box 2: Screening*

General

Complete blood count with differential

Rubella IgG (women of reproductive age)

Hepatitis B and C

Syphilis, gonorrhoea, chlamydia, and HIV-1

PPD, chest radiography if > 10 mm

Stool ova and parasite examination (three morning specimens, different days)

Oral examination and dental referral

Vision and hearing screen

Optional

Varicella IgG

HIV-2 (West Africa)

Urinalysis (if concern about schistosomiasis)

Peripheral blood smear (if concern about malaria)

PPD = purified protein derivative as used with Mantoux testing (tuberculosis)

*Screening items are in addition to recommended tests for healthcare maintenance (pap smear, mammogram, cholesterol testing)

Tuberculosis, parasites, and hepatitis

Tuberculosis is the third leading cause of mortality from infectious diseases after HIV/AIDS and diarrhoeal diseases; for example, one in three people in Africa are infected.13 In one study, 7% of newly arrived refugees had active tuberculosis, and the risk of developing tuberculosis remains high years after immigration.14,15 At the United States Center for International Health, 23% of tuberculosis cases were extrapulmonary.8 For example, back pain (Pott's disease) or menorrhagia (endometrial tuberculosis) may be the presenting symptoms of tuberculosis. Other extrapulmonary sites include the prostate, parotid, chest wall, and pericardium.

Despite mass treatment before embarkation, persistent parasitaemia is relatively common. The most common parasites detected include hookworm (Necator americanus and Ancylostoma duodenale), whipworm (Trichuris trichiura), roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides), and Giardia lamblia.9 Classic complications of parasitaemia include anaemia (hookworm), intestinal obstruction (roundworm), Loeffler's syndrome (pulmonary hypersensitivity or infiltrates due to Strongyloides and Ascaris), cholangiocarcinoma (Opisthorchis sinensis), and bladder cancer (Schistosomiasis hematobium). A screening urinalysis for urinary schistosomiasis is indicated in refugees from areas of high prevalence such as West Africa. Malaria is uncommon in refugees, as most are empirically treated; however, untreated pregnant refugees are at risk.

Hepatitis B is endemic in Africa and South East Asia, with rates of current or past infection as high as 50-80%. Death from cirrhosis or hepatoma occurs in up to one third of carriers who acquired hepatitis B perinatally. We screen for hepatitis C in any patient who has had a previous blood transfusion, ritual female genital surgery, or surgical procedure, and we routinely screen African and South East Asian refugees (prevalence of 5% and 2.5%).16

Mental health and trauma

Tackling the complex mental health needs of refugees is particularly challenging for both primary care providers and mental health professionals. Many studies report refugees to be at a higher risk of psychiatric disorders such as depression, suicide, psychosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance misuse, often directly related to past physical or psychological trauma.17-20 Understanding a patient's trauma history is critical to treating psychiatric and medical disorders. Approximately 5-10% of refugees in the United States have experienced a form of torture, including electric shocks, beatings, caning of the soles of the feet, rape, and forced witnessing of torture or executions.21 Sexual violence is prominent in the torture of women and may be spontaneous or systematic (“rape camps”). The problems of many refugees, however, may not be adequately described by Western psychiatric categories.22 Demoralisation and bereavement may be incorrectly labelled as depression. An effort should be made to simultaneously explore psychiatric symptoms, exposure to trauma, and potential social and economic factors contributing to a refugee's mental health. Referral to social workers, cultural case mediators, and community organisations may be appropriate.

Post-traumatic stress disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder is the most common consequence of violence and describes at least one month of recurrent, painful re-experiencing of a traumatic event, emotional numbing or hyperarousal, and avoidance of trauma related memories.23 Critical factors in developing post-traumatic stress disorder include severity, duration, and closeness of exposure to the trauma. Although studies of drug treatment in refugees with post-traumatic stress disorder are rare, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are considered a good first line treatment.24,25 Earlier studies recommended an 8-12 week drug trial, but recent studies have found symptomatic improvement as soon as 2-5 weeks. However, severely traumatised refugees may fail to respond to drugs alone. Both exposure therapy and cognitive behaviour therapy have been found to be beneficial for post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees.26,27 Treatment may begin with an adequate trial of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; if minimal response occurs, consultation with a psychiatrist is indicated to determine if additional drugs (α blocker), therapy, or both should be added. Psychologists specialising in the mental health of refugees may represent an additional source of expertise, particularly with a form of therapy. Lack of availability of psychiatric care appropriate to culture and language may, however, represent a barrier to effective treatment.28

Additional educational resources

Journal articles

Walker PF, Jaranson J. Refugee and immigrant health care. Med Clin North Am 1999;83: 1103-20 Burnett A, Peel M. Health needs of asylum seekers and refugees. BMJ 2001;322: 544-7 Burnett A, Peel M. Asylum seekers and refugees in Britain: the health of survivors of torture and organised violence. BMJ 2001;322: 606-9

Websites

US Committee for Refugees (www.refugees.org)—Lists statistics, news, and information pertinent to refugees, and lists international refugee assistance organisations

EthnoMed (www.ethnomed.org)—Provides culture specific information on health beliefs and healthcare barriers for multiple refugee and immigrant groups.

Factsheets on hepatitis, breast cancer, and diabetes are translated into several languages

Harvard Program in Refugee Trauma (hprt-cambridge.org)—Provides questionnaires and checklists for assessment of mental health in several languages, including the Harvard trauma questionnaire, Hopkins symptom checklist-25, and a simple depression screen

Research Action and Information Network for the Bodily Integrity of Women (www.rainbo.org)—An international non-governmental organisation working to eliminate the practice of ritual female genital surgery. The website provides information on obtaining technical manuals for healthcare providers

Somatisation

Psychological trauma may present as somatic complaints in refugees. A diagnosis of somatisation disorder requires symptoms of pain (at least four sites), two gastrointestinal symptoms, one sexual symptom, and one pseudoneurological symptom.23 Physical complaints must begin before age 30, result in considerable impairment, and lack a medical cause. Refugees may be at risk for somatisation because psychiatric disease is often not culturally accepted, and somatic rather than psychiatric complaints increased their previous chances of accessing health care. In addition, pain thresholds may be lower in this population as a result of psychological distress and depression. Somatisation occurs more commonly in unemployed and less educated refugees.29,30 Epstein suggests an approach for patients with unexplained somatic symptoms that includes acceptance of suffering, tolerance of uncertainty, and limitation of iatrogenic harm.31 The physician simultaneously considers symptoms, pathological findings, and mental health, focusing care on functional improvement rather than cure.

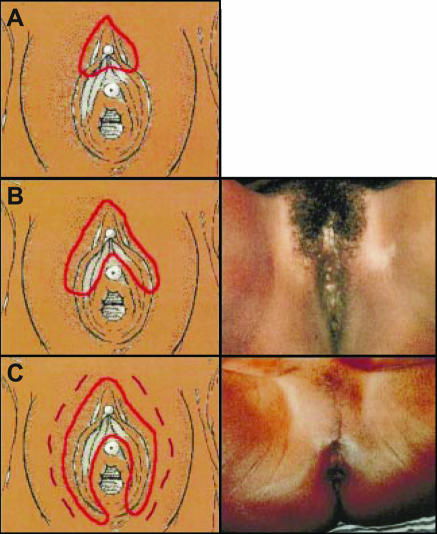

Ritual female genital surgery

Ritual female genital surgery, also known as female circumcision or genital mutilation, is mainly done in Africa and affects 130 million women and girls worldwide.32 Ritual female genital surgery continues to be done for complex cultural reasons, although condemned by the World Health Organization because of its serious health consequences. In 1990 the Centers for Disease Control estimated that 168 000 girls and women in the United States were likely to have undergone ritual female genital surgery, and subsequent Somali immigration greatly increased this number. Although discrete WHO classifications of ritual female genital surgery exist, people doing the procedure are informally trained, resulting in inexact surgical outcomes (figure). Physicians in host countries may encounter long term complications of ritual female genital surgery, including dyspareunia, inability to have intercourse, chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, recurrent urinary tract infection, and scar abscesses. Gynaecology referral for defibulation (take down or revision of ritual female genital surgery) may be indicated for pelvic examination or treatment of resulting medical complications, or before labour and delivery.

Figure 1.

World Health Organization classification for ritual female genital surgery. A (type I or Sunna): excision of the prepuce with or without excision of the clitoris. B (type II): excision of the prepuce and clitoris and partial or total excision of the labia minora. C (type III or pharaonic): excision of part or all of the external genitalia and stitching or narrowing of the vaginal opening. Type IV circumcision (not pictured) describes procedures that do not fit the previous classifications: piercing, cauterisation, or stretching of the clitoris or labia with the aim of narrowing the vagina. Reproduced courtesy of Nahid Toubia, president of the RAINBO organisation

Conclusion

Providing culturally sensitive and competent health care to refugee populations can be as rewarding as it is challenging and often has a major impact on the life of a new refugee. Primary care for refugees begins with understanding reasons for flight and a group's particular exposure to infectious disease and psychological trauma, which may focus medical history and screening. Increased knowledge about the complex medical needs of refugees can help the primary care physician to care more effectively for this special population. A society's moral strength can be measured by how it treats its most vulnerable citizens.

Contributors: KMA and NA made substantial contributions to the intellectual content of the entire text of the manuscript and took active roles in its drafting and revision. LDG's contribution to the manuscript was limited to the content and drafting of sections related to the trauma history and psychiatric diseases. KMA is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Funding: Supported in part by HD-01264 from the National Institutes of Health. The funding source represents a career development award for KMA and had no influence on the contents of the manuscript. LDG's contribution was independent of a funding source. NA is now working for a non-governmental organisation in Afghanistan to improve women's health. Her contribution to the manuscript predated her current position, and this organisation had no influence on her contribution to the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.U.S. Committee for Refugees. World refugee survey 2003. (Available from www.refugees.org/siteindex.cfm)

- 2.United Nations. Convention relating to the status of refugees. New York: United Nations, 1951. [PubMed]

- 3.Miller JM, Boyd HA, Ostrowski SR, Cookson ST, Parise ME, Gonzaga PS, et al. Malaria, intestinal parasites, and schistosomiasis among Barawan Somali refugees resettling to the United States: a strategy to reduce morbidity and decrease the risk of imported infections. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000;62: 115-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinzie JD. Evaluation and psychotherapy of Indochinese refugee patients. Am J Psychother 1981;35: 251-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mollica RF. The trauma story: a phenomenological approach to the traumatic life experiences of refugee survivors. Psychiatry 2001;64: 60-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, Truong T, Tor S, Lavelle J. The Harvard trauma questionnaire: validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992;180: 111-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldfeld AE, Mollica RF, Pesavento BH, Faraone SV. The physical and psychological sequelae of torture: symptomatology and diagnosis. JAMA 1988;259: 2725-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker PF, Jaranson J. Refugee and immigrant health care. Med Clin North Am 1999;83: 1103-20, viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stauffer WM, Kamat D, Walker PF. Screening of international immigrants, refugees, and adoptees. Prim Care 2002;29: 879-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nutman TB, Ottesen EA, Ieng S, Samuels J, Kimball E, Lutkoski M, et al. Eosinophilia in Southeast Asian refugees: evaluation at a referral center. J Infect Dis 1987;155: 309-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muennig P, Pallin D, Sell RL, Chan MS. The cost effectiveness of strategies for the treatment of intestinal parasites in immigrants. N Engl J Med 1999;340: 773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueira M, Christiansen D, Barnett ED. Cost-effectiveness of serotesting compared with universal immunization for varicella in refugee children from six geographic regions. J Travel Med 2003;10: 203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. The world health report 2004—changing history. www.who.int/whr/2004/en (accessed 16 June 2004).

- 14.DeRiemer K, Chin DP, Schecter GF, Reingold AL. Tuberculosis among immigrants and refugees. Arch Intern Med 1998;158: 753-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuber PL, McKenna MT, Binkin NJ, Onorato IM, Castro KG. Long-term risk of tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States. JAMA 1997;278: 304-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debonne JM, Nicand E, Boutin JP, Carre D, Buisson Y. [Hepatitis C in tropical areas.] Med Trop (Mars) 1999;59(4 pt 2): 508-16. (In French.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinzie JD, Boehnlein JK, Leung PK, Moore LJ, Riley C, Smith D. The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and its clinical significance among Southeast Asian refugees. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147: 913-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhui K, Abdi A, Abdi M, Pereira S, Dualeh M, Robertson D, et al. Traumatic events, migration characteristics and psychiatric symptoms among Somali refugees—preliminary communication. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38: 35-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorst-Unsworth C. Adaptation after torture: some thoughts on the long-term effects of surviving a repressive regime. Med War 1992;8: 164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization. WHO/UNHCR mental health of refugees. Geneva: WHO, 1999.

- 21.Pincock S. Exposing the horror of torture. Lancet 2003;362: 1462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watters C. Emerging paradigms in the mental health care of refugees. Soc Sci Med 2001;52: 1709-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994.

- 24.Friedman M, Davidson J, Mellman T, Southwick S. Pharmacotherapy. In: Foa E, Keane T, Friedman M, eds. Effective treatments for PTSD: practice guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. New York: Guilford Press, 2000.

- 25.Smajkic A, Weine S, Djuric-Bijedic Z, Boskailo E, Lewis J, Pavkovic I. Sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine in refugee posttraumatic stress disorder with depression symptoms. J Trauma Stress 2001;14: 445-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otto MW, Hinton D, Korbly NB, Chea A, Ba P, Gershuny BS, et al. Treatment of pharmacotherapy-refractory posttraumatic stress disorder among Cambodian refugees: a pilot study of combination treatment with cognitive-behavior therapy vs sertraline alone. Behav Res Ther 2003;41: 1271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paunovic N, Ost LG. Cognitive-behavior therapy vs exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD in refugees. Behav Res Ther 2001;39: 1183-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Redwood-Campbell L, Fowler N, Kaczorowski J, Molinaro E, Robinson S, Howard M, et al. How are new refugees doing in Canada? Comparison of the health and settlement of the Kosovars and Czech Roma. Can J Public Health 2003;94: 381-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin EH, Carter WB, Kleinman AM. An exploration of somatization among Asian refugees and immigrants in primary care. Am J Public Health 1985;75: 1080-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Westermeyer J, Bouafuely M, Neider J, Callies A. Somatization among refugees: an epidemiologic study. Psychosomatics 1989;30: 34-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epstein R. Somatization reconsidered: incorporating the patient's experience of illness. Arch Intern Med 1999;159: 215-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toubia N. Caring for women with circumcision: a technical manual for providers. New York: Rainbo Publishers, 1999.