Abstract

Biologic drugs represent a substantial progress in the treatment of chronic inflammatory immunologic diseases. However, its crescent use has revealed seldom reported or unknown adverse reactions, mainly associated with anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF). Psoriasiform cutaneous reactions and few cases of alopecia can occur in some patients while taking these drugs. Two cases of alopecia were reported after anti-TNF therapy. Both also developed psoriasiform lesions on the body. This is the second report about a new entity described as 'anti-TNF therapy-related alopecia', which combines clinical and histopathological features of both alopecia areata and psoriatic alopecia. The recognition of these effects by specialists is essential for the proper management and guidance of these patients.

Keywords: Alopecia, Alopecia areata, Dermoscopy, Psoriasis, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

INTRODUCTION

The increased use of biologic drugs has been revealing new adverse effects. The cutaneous reactions described include eczema, erythema, urticaria, lupus-like syndrome and, paradoxically, psoriasis.1 The development of alopecia related to anti-TNF is a possible although seldom reported collateral effect. In this context, alopecia areata (AA), psoriatic alopecia and anti-TNF therapy-related alopecia are described, of which the latter mixes clinical and histopathological characteristics of both psoriatic alopecia and AA.2

Two cases of alopecia associated with anti-TNF therapy were reported, which resulted in cutaneous psoriasiform lesions.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

Male patient, 28 years old, affected by Crohn's disease and treated with infliximab for 3 years, presented alopecia plaques on the scalp and erythematous-scaly lesions in the armpits, navel and perianal region for the last 2 weeks. He denied personal or family history of psoriasis. During the physical examination, 2 alopecia plaques were found in the left parietal region. The oldest lesion, smooth and normochromic, showed clinical and dermoscopic aspects of AA: black spots and exclamation-mark hairs, whereas the most recent one presented erythema and desquamation (Figures 1, 2 and 3). Histopathology demonstrated extensive parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, dilated dermal papillae containing tortuous capillaries and mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate, involving all levels of intra and perifollicular structure and intense miniaturization of hair follicles (Figure 4). Direct mycological examination was negative. Daily treatment was started with clobetasol gel, coal tar shampoo, intralesional corticoid in monthly application on the scalp and tacrolimus 0.1% on body lesions. Infliximab was maintained and after 3 months the desquamation disappeared and there was complete hair regrowth and remission of cutaneous lesions.

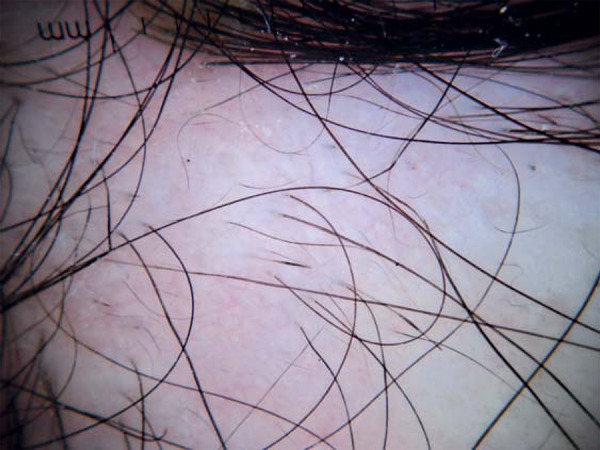

FIGURE 1.

Dermoscopy of alopecic plaque. Exclamationmark hairs in the center, vellus hairs and black spots on the edges of the plaque (10x magnification)

FIGURE 2.

Alopecic plaques in different phases of evolution. Most recent plaque with erythema and desquamation and the oldest one normochromic and smooth

FIGURE 3.

Dermoscopy of desquamative alopecic plaque. Detail of desquamation

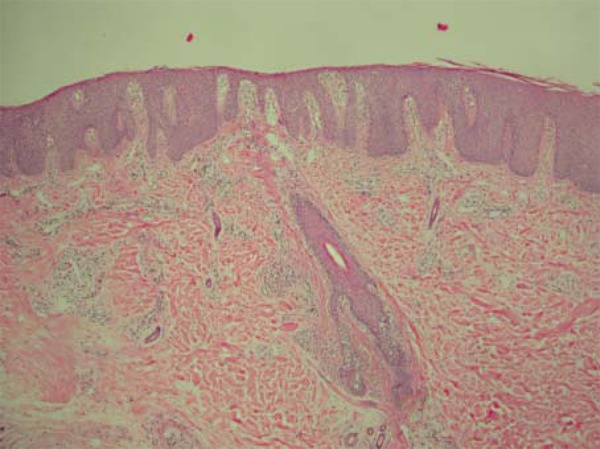

FIGURE 4.

Histopathology of alopecia plaque with desquamation (HE). Extensive parakeratosis, epidermal hyperplasia, dilated dermal papillae containing tortuous capillaries and mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the interior and around miniaturized follicular structure (HE 100x)

Case 2

Female patient, 14 years old, had been treated with infliximab for 6 months due to Crohn's disease. After 4 months of treatment, she presented erythematous-desquamating lesions on the body and alopecia plaques with desquamation of the scalp. She denied personal or family history of psoriasis. At the physical examination, she presented erythematous-desquamating plaques on the trunk, armpits, pubic region, breasts, plantar regions, elbows and knees. On the scalp, alopecia desquamating plaques were detected in the bilateral frontal and parietal region (Figure 5). Trichoscopy revealed tortuous vessels compatible with psoriasis (Figure 6). Histopathology of the scalp revealed hyperkeratosis which extended to the follicular ostia, small foci of parakeratosis, pronounced miniaturization with only 50% of hair terminals in anagen and mononuclear infiltrate, discrete perivascular and multifocal intrafollicular. On the trunk a slight, irregular acanthosis was observed with hyperkeratosis, non-confluent parakeratosis and neutrophilic aggregates in the stratum corneum.

FIGURE 5.

Detail of alopecia plaques. Presence of erythema and desquamation

FIGURE 6.

Dermoscopy with polarized light and interface liquid of alopecia plaque with desquamation. Areas of atrichia and thick, tortuous capillary loops in the perifollicular region associated with balled capillary loops in the periphery of the plaque (20x magnification)

Coal tar shampoo was prescribed, along with betamethasone cream on the scalp, LCD lotion 6% and mometasone on body lesions. After 5 months, there was hair regrowth and remission of cutaneous lesions. Infliximab was maintained.

DISCUSSION

The estimated prevalence of psoriasiform eruptions during use of anti-TNFα is between 1.5 and 5%, mainly associated with infliximab.1 One of the proposed mechanisms was blocking TNF receptors, which would increase the production of interferon-α by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in genetically predisposed individuals. Interferon-α would become then the cytokine responsible for activation and amplification of pathogenic T-cells.3 In a revision of psoriasis cases induced by anti-TNF in patients with inflammatory intestinal disease, the flexural area was affected in 31% of the cases and the scalp in 42%, although alopecia has not been described.4 Reports of psoriasis on the scalp associated with alopecia induced by anti-TNF are rare.5,6 Recently, a new kind of psoriatic alopecia / alopecia areata-like reaction secondary to anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α therapy has been described based on the report of 3 alopecia cases that mixed clinical and histopathological characteristics of AA and psoriasis.2 For this diagnosis, it would be necessary to meet the following criteria: (1) development of psoriasiform lesions after treatment with anti-TNF, (2) absence of previous psoriasis history, (3) alopecia plaque(s) on the scalp, (4) erythematous - desquamative plaques on the scalp and/or pustular lesions on the scalp and (5) development of psoriasiform rash on the body after treatment.2 All patients in this report presented all of these characteristics.

In the histopathology of alopecia induced by anti-TNF, besides classic psoriasiform epidermal changes, alterations similar to AA ones are observed on the dermis, such as intense miniaturization, increase in catagen and telogen hairs and peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate in terminal hairs. Numerous plasmocytes and eosinophils were also observed.2 We computed the following discrepancies in the histological findings of Doyle et al.: 1) The lymphocytic infiltrate was not restricted to the peribulbar region, occupying all levels of the follicular structure. This does not invalidate AA dermal findings, since the "swarm of bees" peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrate, typical of AA, is more often associated with the acute phase.7 Moreover, in psoriatic alopecia there is no lymphocytic infiltrate in the peribulbar region; 2) Eosinophils and plasmocytes were not identified in the inflammatory infiltrate.8 Eosinophils were found in 44% of the 109 cases of AA by Peckhametal and plasmocytes are normal components of the occipital scalp area.7,9 This way, we believe that the presence of eosinophils and plasmocytes may not be fundamental to characterize this type of alopecia.

This combination of clinical, histopathological and dermoscopic characteristics of psoriatic alopecia and AA reinforce the diagnosis of psoriatic alopecia / alopecia areata-like reaction secondary to anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α therapy. The main differential diagnoses are AA, psoriatic alopecia, pityriasis amiantacea and tinea capitis.

There is no consensus regarding maintenance or suspension of anti-TNFα in face of cutaneous reaction triggered by these drugs. Upon revising 16 cases of AA induced by anti-TNFα, treatment was suspended in 7 cases, and only 2 presented complete hair regrowth.10 For psoriasis induced by anti-TNFα they are usually maintained and topical treatment with corticosteroids and vitamin D analog allow for total or partial remission of the cutaneous lesions.3 Iborra et al. recommend the suspension of anti-TNFα when the lesions cover more than 5% of body surface, are intolerable or if that is what the patient wishes.1 For these patients, infliximab was maintained due to the small extension of psoriasiform lesions, achieving good clinical evolution.

The objective of this report was to demonstrate the first 2 cases described in national literature of alopecia induced by anti-TNFα which fall within the category described as psoriatic alopecia / alopecia areata-like reaction secondary to anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-α therapy, pointing out histopathological differences regarding the only previous publication and emphasizing dermoscopic signs as an auxiliary diagnostic tool.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests: none

Financial Support: none

How to cite this article: Ribeiro LBP, Rego JCG, Duque-Estrada B, Bastos RP, Maceira JMP, Sodré CT. Alopecia secondary to Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha therapy. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(2):232-5.

Work performed at Instituto de Dermatologia Professor Rubem David Azulay - Santa Casa de Misericórdia do Rio de Janeiro (IDPRDA- SCMRJ) - Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brazil.

References

- 1.Iborra M, Beltran B, Bastida G, Aguas M, Nos P. Infliximab and adalimumab-induced psoriasis in Crohn's disease: A paradoxical side effect. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:157–161. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doyle LA, Sperling LC, Baksh S, Lackey J, Thomas B, Vleugels RA, et al. Psoriatic alopecia/alopecia areata-like reactions secondary to anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor-a Therapy: A Novel Cause of Noncicatricial Alopecia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:161–166. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181ef7403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collamer AN, Battafarano DF. Psoriatic skin lesions induced by tumor necrosis factor antagonist therapy: clinical features and possible immunopathogenesis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;40:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cullen G, Kroshinsky D, Cheifetz AS, Korzenik JR. Psoriasis associated with antitumor necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a new series and a review of 120 cases from the literature. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1318–1327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medkour F, Babai S, Chanteloup E, Buffard V, Delchier JC, Le-Louet H. Development of diffuse psoriasis with alopecia during treatment of Crohn's disease with infliximab. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010;34:140–141. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perman MJ, Lovell DJ, Denson LA, Farrell MK, Lucky AW. Five cases of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced psoriasis presenting with severe scalp involvement in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2012;29:454–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2011.01521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peckham SJ, Sloan SB, Elston DM. Histologic features of alopecia areata other than peribulbar lymphocytic infiltrates. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bardazzi F, Fanti PA, Orlandi C, Chieregato C, Misciali C. Psoriatic scarring alopecia: observations in four patients. Int J Dermatol. 1999;38:765–768. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews diseases of the skin. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferran M, Calvet J, Almirall M, Pujol RM, Maymó J. Alopecia areata as another immune-mediated disease developed in patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-a blocker agents. Report of five cases and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:479–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]