Abstract

The ideal standards model suggests that greater consistency between ideal standards and actual perceptions of one’s relationship predicts positive relationship evaluations; however, no research has evaluated whether this differs across types of ideals. A self-determination theory perspective was derived to test whether satisfaction of intrinsic ideals buffers the importance of extrinsic ideals. Participants (N=195) in committed relationships directly and indirectly reported the extent to which their partner met their ideal on two dimensions: intrinsic (e.g., warm, intimate) and extrinsic (e.g., attractive, successful). Relationship need fulfillment and relationship quality were also assessed. Hypotheses were largely supported, such that satisfaction of intrinsic ideals more strongly predicted relationship functioning, and satisfaction of intrinsic ideals buffered the relevance of extrinsic ideals for outcomes.

Keywords: romantic relationships, self-determination theory, ideal standards model, need fulfillment

The desire to establish and maintain interpersonal connections with others is considered a basic human motive (e.g., Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Deci & Ryan, 1991). Meeting our romantic partner’s ideals on various dimensions should influence the extent to which they are satisfied with the relationship, and research on the ideal standards model (ISM; Fletcher, Simpson, Thomas, & Giles, 1999) has shown exactly that. However, while we can speculate that not all ideals are necessarily equal when it comes to predicting satisfying romantic relationships, this has not yet been empirically evaluated. Furthermore, self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 2000) makes a distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic aspirations and goals and their association with psychological and relational well-being. The current research integrates the ISM with SDT to test whether perceived discrepancy on different types of ideals differentially predicts relationship outcomes.

The Ideal Standards Model

Research on the ISM (Fletcher et al., 1999; see Eastwick, Luchies, Finkel, & Hunt, 2013, for review and meta-analysis) has shown that judgments about a specific relationship are partly based on the degree of consistency between expectations or ideals for one’s relationship and actual perceptions of one’s relationship. More specifically, individuals in romantic relationships tend to compare ideals (i.e., what they ideally want in a partner and relationship) to perceptions (i.e., how they currently view their partner and relationship), and thereby derive their relationship satisfaction from this perceived discrepancy. The model also focuses on the cognitive and behavioral processes (e.g., partner regulation) involved in making these comparisons.

Partner and relationship ideals function as chronically accessible information that likely precedes and potentially causally affects judgments and decisions in relationships (Fletcher et al., 1999). The ISM contends that the more closely perceptions of the current partner and relationship match individuals’ ideal standards, the more favorable relationship evaluations will be. Through multiple studies and multiple operationalizations of discrepancy between ideals and perceptions, research on the ISM has found that higher ideal-perception consistently predicts greater perceived quality of the partner and the relationship (Campbell, Simpson, Kashy, & Fletcher, 2001; Fletcher et al., 1999, Fletcher, Simpson, & Thomas 2000a), in addition to lower relationship dissolution rates (Fletcher et al., 2000a). Recent research used survival analysis to examine the utility of consistency between ideals and perceptions in predicting the likelihood of divorce (Eastwick & Neff, 2012). Results suggested that when the consistency was conceptualized as a match in pattern (i.e., the within-person correlation of ideals with a partner’s traits across all traits), consistency predicted stability with an effect size larger than most established risk factors for divorce. However, consistency was conceptualized as a match in level (i.e., high ideal preference for a trait with the presence of that trait in the partner) was unrelated to likelihood of divorce.

Further, the ISM suggests that individuals regularly make cognitive comparisons between their ideal standards and perceptions of their current partner and relationship on multiple content-specific dimensions. An “ideal” partner or relationship is not simply a nebulous construct; rather, people tend to associate distinct characteristics with ideal partners (e.g., “My ideal partner is very intelligent,” “My ideal partner is very attractive”) and assign greater importance to particular attributes. Fletcher and colleagues (1999) used confirmatory factor analysis (Fletcher et al., 1999) to support a model with the 69 ideal characteristics loading onto five partner and relationship dimensions (i.e., partner warmth/trustworthiness, partner vitality attractiveness, partner status/resources, relationship intimacy/loyalty, relationship passion), which then loaded onto two overarching hierarchical factors: warmth/loyalty (e.g., understanding, kind, supportive, honest) and vitality/status/passion (e.g., attractive, successful, financially secure, exciting). Although previous research has suggested gender differences in importance of attractiveness and resources such that men have higher ideals for attractiveness and women have higher ideals for status and resources (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993), Fletcher and colleagues (1999) found that both the factor structure (both the lower order and higher order paths) replicated across gender, lending further support for the two-factor model. Further, in their review and meta-analysis, Eastwick and colleagues (2013) suggest that although gender differences in ideals are present during the early or formative stages, there are relatively few, if any, gender differences in the importance of ideals in established romantic relationships.

We believe, based on tenets of self-determination theory, that relationship quality may be derived from these two overarching dimensions differently. In other words, it is possible that not all characteristics are weighted equally in predicting relationship outcomes. For example, satisfaction of intimacy and loyalty in the relationship may be more important for relationship quality than the satisfaction of physical attractiveness and financial resources. Further, partners satisfying intimacy or loyalty ideals might make the satisfaction of physical attractiveness and financial resources seem less essential to relationship quality. It is possible that to the extent that partners meet ideals on more intrinsically valued attributes (e.g., being understanding, kind, and supportive), their perceived status on more extrinsically valued attributes (e.g., being physically attractive, successful, and having financial resources) may become less relevant in relationship evaluations. Using the SDT theoretical framework, the current research tested whether meeting intrinsically valued ideals, which are more consistent with basic psychological needs, buffers the relevance of meeting extrinsically valued ideals in predicting relationship outcomes.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Ideals

Self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000) has distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic values and aspirations (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996; Sheldon, Ryan, Deci & Kasser, 2004). Although not specifically in the domain of romantic relationships, this prior work has found that two key factors capture individuals’ aspirations and values. Extrinsic aspirations were defined as those that depend on the contingent reactions of others and are engaged in as a means to some other end. Further, these extrinsic aspirations less directly satisfy basic psychological needs as put forth by SDT. Extrinsic aspirations include financial success, social recognition, and possessing an attractive image (Kasser & Ryan, 1996). Intrinsic aspirations, on the other hand, were defined as those that are expressive of desires that are congruent with actualization and growth tendencies, and genuinely relating to others, thereby more directly satisfying basic psychological needs. These are generally not a means to some other end, but rather support growth and closeness. Specifically, intrinsic aspirations include emotional intimacy, personal growth, and community contribution based on their congruence with the movement toward self-actualization or integration (Ryan, Sheldon, Kasser, & Deci, 1996) and their consistency with basic psychological needs. These goals are perceived as intrinsic in the sense that they are inherently valuable and satisfying to the individual, instead of being conditional on others’ evaluations or as compensatory to deficits of basic psychological need fulfillment. From both theoretical and empirical perspectives, being motivated by intrinsic goals—rather than by extrinsic goals—predicts better psychological well-being.

According to SDT, intrinsic aspirations are more closely linked to basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Kasser & Ryan, 1996; Sheldon et al., 2004). The need for autonomy represents the need to feel that one’s behavior is personally endorsed and initiated from values that are integrated within oneself (Deci, 1980; Deci & Ryan, 2000). The need for competence reflects the need to feel competent and effective in one’s behaviors. Finally, the need for relatedness represents the desire to experience intimacy and connection with others, and was referred to as the need to belong by Baumeister and Leary (1995). The need for relatedness also derives from perspectives on intimacy and closeness (Reis & Patrick, 1996), demonstrating that feeling understood, validated, and cared for results in healthier psychological and relationship functioning.

Fulfillment of these three psychological needs is associated with improved psychological (Reis, Sheldon, Gable, Roscoe, & Ryan, 2000; Sheldon et al., 1996) and relational well-being (Patrick, Knee, Canevello, & Lonsbary, 2007). For example, across several samples, Patrick et al. (2007) found that: (a) fulfillment of each need individually predicted both individual and relationship well-being across a variety of outcomes, with relatedness being the strongest unique predictor; (b) both partners’ need fulfillment uniquely predicted one’s own relationship functioning and well-being; and (c) those with greater need fulfillment within their relationship displayed relatively higher relationship quality after disagreements (Patrick et al., 2007). This basic psychological needs perspective suggests that high quality close relationships involve more than simply feeling satisfied; relational well-being occurs when the relationship context supports the basic needs of both partners, promoting autonomous motivation for being in the relationship, in turn facilitating how the couple approaches and manages disagreements and conflicts. In this way, fulfillment of basic psychological needs within one’s relationship involves more than feeling satisfied – it involves fully functioning relating between partners.

The ideals along the warmth-trustworthiness dimension of the ISM facilitate fulfillment of SDT’s three basic psychological needs. For example, traits such as being sensitive, warm, and a good listener are likely to promote the experience of relatedness by facilitating connection and belonging. Qualities such as respecting and understanding one’s partner support the experience of competence by validating one’s worth. Finally, traits such as being accepting and open-minded likely support one’s autonomy through allowing one to express who one is without judgment. Conversely, traits along the vitality-status-passion dimension (e.g., attractiveness, status) may not be as closely tied to need fulfillment as they are usually means to some other ends. These ideals may be more superficial and are generally considered external indicators of worth relative to intrinsic goals. Further, extrinsic goals are less directly linked to the satisfaction of psychological needs (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996), and pursuing these goals for more extrinsic reasons contributes to poorer well-being (Sheldon et al., 2004).

Meeting intrinsic aspirations should, therefore, predict better psychological health and well-being in a number of domains. Using varied measurement approaches, samples, and indices of well-being, research has found that the relative importance of extrinsic to intrinsic goals, aspirations, and values predicts poorer health and well-being (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996; Ryan et al., 1999; Sheldon et al., 2004). Thus, while meeting extrinsic goals may not be inherently negative, the pursuit of extrinsic goals can be at the expense of intrinsic goals that are more likely to satisfy basic psychological needs. In the domain of close relationships, meeting relatively intrinsic partner ideals is more closely tied to need fulfillment, and thus, should predict relational well-being and functioning to a greater extent than meeting more extrinsic ideals. For instance, research has found that intrinsic, intangible investments such as disclosure and time with partners are more important to commitment than extrinsic, tangible investments such as shared possessions (Goodfriend & Agnew, 2008). As such, the degree to which a partner fulfills intrinsic ideals should be a more important predictor of satisfaction than how well a partner meets extrinsic ideals. Importantly, we do not expect meeting extrinsic ideals to negatively predict satisfaction, as there is no reason to assume that partners who also have appealing extrinsic features (e.g., attractive, financially secure) also have less intrinsically appealing features (e.g., warmth, loyalty).

Deci and Ryan (2000) propose in their review that individuals attempt to compensate for lack of intrinsic aspirations by placing more relative importance on extrinsic goals. Although people should naturally place more value on ideals that support basic psychological needs, when these needs are not met, increasing value may be placed on extrinsic aspirations or ideals. Recent research has provided some support for this in romantic relationships, such that people who felt fulfilled on relatedness on one day reported increased valuation of relatedness the next day (Moller, Deci, & Elliot, 2010). With the ISM, it is possible that, although intrinsic ideals should generally predict satisfaction more than extrinsic ideals, when partners do not meet intrinsic ideals, increasing value may be placed on extrinsic ideal consistency. That is, people may compensate for a lack of intrinsic ideal consistency by relying more on extrinsic ideals such as attractiveness or status for a sense of satisfaction. Thus, we expect that people will compensate for partners not meeting intrinsic ideals by focusing on extrinsic ideals; the extent to which partners meet extrinsic ideals should only predict satisfaction when intrinsic ideals are not met.

Current Study

This research integrates dimensions from the ISM with goals and aspirations as posited by SDT. Previous research asked participants how much they loved their partner after being reminded of either extrinsic or intrinsic rewards that they received from their partner (Seligman, Fazio, & Zanna, 1980). Results indicated that those who were induced to adopt an extrinsic relationship mindset reported lower levels of love for their partner. A similar distinction can be made based on SDT with regard to romantic partner ideals. Extrinsic attributes may be defined as relatively observable, superficial, and explicit to people outside of the relationship, and tend to be valued for their role in gaining attention, popularity, fame, physical attraction, and resources. Further, these extrinsic attributes are less directly relevant to satisfaction of basic psychological needs. In other words, extrinsic attributes tend to be valued as means to other ends instead of promoting authenticity, growth, and intimacy. Intrinsic attributes can be defined as relatively observable to only those in the relationship, and tend to be valued for their inherent benefit in authentic self-expression, developing the relationship, growing intimacy, closeness, acceptance, and relationship well-being. Thus, the two higher-order dimensions of the ISM appear to map on to the intrinsic and extrinsic distinction derived from SDT. The ISM warmth/loyalty factor is captured by intrinsic attributes such as being understanding, kind, supportive, and honest – qualities that seem inherent to closeness, trust, and intimacy. In contrast, the ISM vitality/status/passion dimension is captured by attributes such as being attractive, successful, and financially secure – qualities that are valued for their role in gaining approval, popularity, fame, and wealth (i.e., means to other ends). To corroborate this notion, pilot data were collected to test whether vitality/status/passion ideals were perceived as less intrinsic than warmth/loyalty ideals (presented below). As additional support for the SDT framework, we tested whether warmth/loyalty ideals were rated as satisfying the three basic psychological needs to a higher extent than vitality/status/passion ideals.

The current research extends the close relationships literature by integrating the ISM and constructs from SDT to explore whether certain ideals are more important than others in predicting relationship quality. We began with the ISM assumption that perceiving that one’s ideals are met generally predicts relationship satisfaction (even if the ideals are less intrinsic). Thus, we first hypothesized that previous results on the ISM would replicate. That is, relationship quality would be predicted by the general degree of consistency between one’s ideal standards and perceptions of one’s current romantic partner and relationship (i.e., ideal-perception consistency using all target items; Hypothesis 1). While pursuit of more extrinsic goals can detract from pursuit of more intrinsic goals that directly satisfy needs, there is nothing inherently negative about more extrinsic ideals being fulfilled. However, because intrinsic goals are more directly tied, conceptually, to healthier well-being and higher satisfaction of basic psychological needs, we also hypothesized that satisfaction of intrinsic ideals would be more strongly predictive of relationship quality than relatively extrinsic ideals (Hypothesis 2). Finally, based on the compensatory model of need fulfillment (Deci & Ryan, 2000), we expected that when intrinsic ideals are met, extrinsic ideals would become less relevant for relationship quality (Hypothesis 3). Thus, based on SDT, satisfaction of intrinsic ideals would buffer the relevance of satisfying extrinsic ideals, in the form of an intrinsic ideal-perception consistency×extrinsic ideal-perception consistency interaction predicting relationship outcomes.

Method

Pilot Studies

Intrinsic/extrinsic ideals

To ensure consistency between the warmth/loyalty ISM dimension and the intrinsic SDT dimension, and between the vitality/status/passion ISM dimension and the extrinsic SDT dimension, undergraduates (N = 56) evaluated the 69 ideals from the ISM on the extent to which they perceived each dimension as intrinsic versus extrinsic. Qualities were defined in accord with Kasser and Ryan’s (1993, 1996) intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Participants were instructed, “The following are characteristics of relationship partners. For each characteristic, please rate where they fall on the continuum of extrinsic to intrinsic qualities.” The definition for intrinsic qualities was as follows: “Intrinsic qualities tend to be valued for their inherent benefit in developing the relationship, growing intimacy, closeness, acceptance, and relationship growth. These qualities are more connected to being who one really is and less about showing others what they want to see.” The definition for extrinsic qualities was as follows: “Extrinsic qualities tend to be valued for their role in gaining attention, popularity, fame, physical attraction, and resources. These qualities are less connected to being who one really is and more about showing others what they want to see.” Participants rated each of the 69 ISM attributes from 1 (Completely Extrinsic) to 7 (Completely Intrinsic). Results utilizing a dependent samples t-test demonstrated that the characteristics on the ISM’s warmth/loyalty dimension (e.g., reliable, supportive, trustworthy, considerate) were perceived as more intrinsic than the characteristics on the vitality/status/passion dimension (e.g., sexy, dresses well, appropriate ethnicity, financially secure), t(55) = 5.54, p < .001, r = .60. Accordingly, warmth/loyalty and status/vitality/passion ideals are henceforth referred to as intrinsic and extrinsic, respectively.

Ideals and need fulfillment

We further evaluated whether intrinsic ideals, relative to extrinsic ideals, were rated as more highly satisfying the three basic psychological needs. Undergraduates (N = 56) rated each of the 69 ideal characteristics on the extent to which they fulfilled needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (1 = Not at All, 7 = Very Much). Results utilizing dependent samples t-tests showed that the warmth/loyalty (intrinsic) ideals were rated as satisfying each of the three needs to a higher extent than the vitality/status/passion (extrinsic) ideals (all ps < .001).

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 218 undergraduates at a large southwestern university who were currently in a romantic relationship for at least three months. Participants completed the study online in exchange for psychology course extra credit. To ensure high quality data, six questions were embedded within the survey to confirm that participants were paying attention (e.g., “Please select ‘Do not agree at all’ for this question”). Those who answered more than two of the verification questions incorrectly were removed (n = 23). The final sample consisted of 195 undergraduates (86.6% female). There were no significant differences between the initial and final samples in age or gender. The average age was 23.35 (SD = 6.11) years and the average relationship length was 3.39 (SD = 3.93) years. With regard to relationship status, 4.6% of participants reported casually dating, 49.2% reported exclusively dating, 25.7% reported nearly engaged, 5.1% reported being engaged, and 15.4% reported being married. The sample was ethnically diverse, with 29.6% Hispanic/Latino, 28.5% Caucasian, 16.9% Asian/Pacific Islander, 15.1% African American, and 9.9 % who selected “Other.”

Measures

Ideal-perception consistency

Two approaches (one direct and one indirect) to operationalizing ideal-actual discrepancy were used to improve construct validity and address confounds of using a single method. The direct items asked participants to what extent their partner and relationship met their ideal standards on various dimensions. The indirect items asked participants how important various dimensions are in describing their ideal partner and relationship in addition to items asking to rate how accurately each dimension matches their partner and relationship. The direct scores were not transformed, whereas the indirect measurement of ideals was utilized to compute a discrepancy score based on the covariance approach, in which ratings of ideals were residualized from current perceptions. The direct and covariance approaches to calculating discrepancy scores have produced reliable and valid results in prior research on the ISM (e.g., Campbell et al., 2001; Fletcher et al., 1999, 2000a; Overall, Fletcher, & Simpson, 2006).

Direct items measuring discrepancy

The direct method had participants compare their current partner to their ideal partner (i.e., “how much does your current partner match a given attribute of your ideal partner?”) and their current relationship to their ideal relationship (i.e., “how does your current relationship match a given attribute of your ideal relationship?”) on several individual and interpersonal traits (from the Partner Ideal Scale and Relationship Ideal Scale; Fletcher et al., 1999) using 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = Does not match my ideal at all, 7 = Completely matches my ideal). The partner scales consisted of three dimensions: warmth/trustworthiness (approximately 20 items: e.g., understanding, kind; α = .96), vitality/attractiveness (approximately 15 items: e.g., outgoing, sexy; α = .95), and status/resources (approximately 10 items: e.g., successful, financially secure; α = .82). The relationship scales consist of two dimensions: intimacy/loyalty (approximately 15 items: e.g., caring, honest, support; α = .97) and passion (approximately 10 items: e.g., challenging, fun, exciting; α = .93). Thus, a total of 69 items were assessed. These items were presented randomly. All items within each dimension were averaged, with higher scores indicating a closer match between the participant’s ideal and perception on a given dimension. The two warmth/trustworthiness dimensions were averaged, and the three status/vitality/resources dimensions were averaged, leaving a final score of warmth/trustworthiness (intrinsic) and vitality/status/passion (extrinsic).

Indirect measures: Partner/relationship ideals

The 69 items were constructed from the Partner and Relationship Ideal Scales (Fletcher et al., 1999) and were identical to the items used in the direct discrepancy approach. These scales have demonstrated good internal reliability, test-retest reliability, and convergent and predictive validity when used to assess the importance of partner and relationship ideal standards (Campbell et al., 2001; Fletcher et al., 1999, 2000a). Participants rated the ideal partner in terms of “the importance that each item has in describing your ideal partner in a close relationship.” Each item was answered on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Very unimportant, 7 = Very important). The same format was used for the ideal relationship items, with participants being asked to rate each item “in terms of the importance that each item has in describing your ideal close relationship.” Reliability (α) was .95 for intrinsic ideals and .95 for extrinsic ideals.

Indirect measures: Partner/relationship perceptions

Participants also completed an adaptation of the partner and relationship ideal scales that assessed judgments of ideal-related perceptions in their current relationships. The partner perception scale asked participants to “rate each item in terms of how accurately each term describes your actual partner in your current relationship.” The relationship perception scale asked participants to “rate each item in terms of how accurately each one describes your actual current romantic relationship.” The items were identical to those described in the partner and relationship ideal scales, with each item being accompanied by a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Not at all like my partner/relationship, 7 = Very much like my partner/relationship). Reliability (α) was .98 for intrinsic perceptions and .95 for extrinsic perceptions.

Ideal-perception discrepancy score calculation for the indirect covariance approach

To better understand the effects of the components of the discrepancy (Griffin, Murray, & Gonzales, 1999), a second discrepancy index was computed that does not confound the current perception and ideal standard components. This residual discrepancy involved examining current perception ratings controlling for ideal standard ratings, thus resulting in a residualized variable that reflects what one sees favorably in one’s partner that is not part of one’s ideal standard.

Previous research has employed a similar residualized index of perception-ideal discrepancy (Knee, Nanayakkara, Vietor, Neighbors, & Patrick, 2001; Overall et al., 2006). More negative residuals reflect a greater discrepancy between current perceptions and ideal standards relative to the rest of the sample. This direction was chosen rather than the alternative (examining the association of one’s ideal partner controlling for one’s current partner) because it has been employed previously in the ISM literature (Overall et al., 2006), and theoretically, we were interested in what one sees in one’s partner that is not part of one’s ideal.

Relationship quality

The Perceived Relationship Quality Components inventory (PRQC; Fletcher, Simpson, & Thomas, 2000b) was selected as the indicator of relationship quality based on its previous use with research on the ISM (Fletcher et al., 2000a; Overall et al., 2006). It measures six components (i.e., love, passion, commitment, trust, satisfaction, and closeness). Three items assess how they perceive their relationship on each component on 7-point Likert-type scales (1 = Not at all, 7 = Extremely). Example items are “How close is your relationship?” How much do you love your partner?” and “How dependable is your partner?” Past studies have used confirmatory factor analysis (see Fletcher et al., 2000b) to show that the inventory possesses good internal reliabilities for each first-order construct and a good fit for the model in which the indicator variables load on the six first-order constructs, which in turn load on a second-order factor representing overall perceived relationship quality (α = .96). Results were also performed examining each of the six subscales separately (see Footnote 1).

Relationship need fulfillment

Need satisfaction in relationships (NSR; La Guardia, Ryan, Couchman, & Deci. 2000) is a commonly used measure of relationship quality in the self-determination literature (e.g., Patrick et al., 2007; Uysal, Lin, Knee, & Bush, 2012). Need satisfaction in relationships assesses relationship satisfaction in terms of three fundamental psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness), and has been shown to predict a wide range of indicators of relationship quality (Patrick et al., 2007). Nine items measured the extent to which psychological needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are being satisfied by one’s romantic partner. All items began with the stem, “When I am with my romantic partner…” Participants indicated their agreement to each item on a Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 7 = Strongly agree). The need for autonomy represents the need to feel that one’s behavior is personally endorsed and choiceful (example item, “I feel free to be who I am”). The need for competence represents the need to feel effective at what one does (example item, “I feel very capable and effective”). The need for relatedness represents the need to feel a sense of closeness and intimacy with others (example item, “I feel loved and cared about”). Although the three needs function separately and combine additively to predict outcomes (Deci & Ryan, 2000), research has employed it as a single aggregated construct (Deci et al., 2001) that functions as an overall index of need satisfaction (α = .90).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations for each of the major variables in the study. Overall, perceptions were stronger predictors of relationship quality and need fulfillment than were ideals. Intrinsic ideals, but not extrinsic ideals, were significantly associated with increased relationship quality and need fulfillment. This finding is consistent with previous research examining intrinsic relative to extrinsic goals (e.g., Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996; Ryan et al., 1999; Sheldon et al., 2004). Need fulfillment was highly correlated with relationship quality. Additionally, intrinsic and extrinsic ideals were positively correlated, as with the aspirations literature (e.g., Kasser & Ryan, 1996). We interpret this positive correlation as individual differences in level of expectations, such that some people have higher ideals, overall, than do others.

Table 1.

Means and Zero-order Correlations among All Major Study Variables

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Direct Consistency-Intrinsic | -- | |||||||

| 2. Direct Consistency: Extrinsic | .82*** | -- | ||||||

| 3. Ideal: Intrinsic | .21** | .29*** | -- | |||||

| 4. Ideal: Extrinsic | .18* | .28*** | .70*** | -- | ||||

| 5. Perception: Intrinsic | .93*** | .76*** | .26*** | .18* | -- | |||

| 6. Perception: Extrinsic | .74*** | .89*** | .43*** | .39*** | .80*** | -- | ||

| 7. Relationship Quality | .81*** | .73*** | .19** | .10 | .80*** | .70*** | -- | |

| 8. Need Fulfillment | .77*** | .64*** | .15* | .03 | .75*** | .61*** | .78*** | -- |

|

| ||||||||

| Mean | 5.93 | 5.76 | 6.55 | 5.76 | 5.88 | 5.61 | 5.97 | 5.94 |

| Standard Deviation | 1.22 | 1.06 | .46 | .84 | 1.13 | .96 | 1.14 | 1.16 |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Primary Analyses

Hypothesis 1: Ideal-perception consistency and relationship quality

The first hypothesis was that the original postulates of the ISM would replicate: Collapsing across dimensions, higher ideal-perception consistency should predict increased reports of relationship quality and need fulfillment. This was evaluated using both the direct and indirect approaches to discrepancy. Specifically, regression equations evaluated the association between the direct ideal-perception consistency score and relationship outcomes and the association between the perception score and relationship outcomes, controlling for ideals. Results supported the hypothesis using both direct and indirect assessments of discrepancy. Collapsing across dimensions, higher ideal-perception consistency predicted higher relationship quality using the direct approach, β = .826, t(193) = 20.38, p < .001, and the indirect approach, β = .849, t(193) = 19.20, p < .001. Further, higher ideal-perception consistency predicted higher need fulfillment using the direct approach, β = .763, t(193) = 16.38, p < .001, and the indirect approach, β = .790, t(193) = 15.72, p < .001.

Hypothesis 2: Intrinsic versus extrinsic ideals

The second hypothesis was that fulfillment of intrinsic ideals would more strongly predict positive relationship outcomes than fulfillment of extrinsic ideals. Dimensions were created by using the model previously reported by Fletcher and colleagues (1999). Analyses were computed with the five partner and relationship ideal dimensions collapsing onto two superordinate factors: Intrinsic (i.e., warmth/loyalty) and extrinsic (i.e., status/vitality/passion). Hierarchical regression analyses tested the role of intrinsic ideal-perception discrepancy and extrinsic ideal-perception discrepancy in predicting relationship quality and need fulfillment. The first model included only the main effects of the predictors; the second equation also included the two-way interaction term. Results from the hierarchical regression analyses are presented for both discrepancy score techniques and both relationship outcomes in Tables 2 and 3. As shown, ideal-perception consistency on intrinsic ideals (βs ranging from .63 to .73; average β = .67) more strongly predicted both relationship outcomes than ideal-perception consistency on extrinsic ideals (βs ranging from .05 to .24; average β = .15).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Relationship Outcomes: Direct Approach

| Outcome | Model | B | SE B | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRQC (Relationship Quality) | Step 1: Main-Effects | ||||

| Intrinsic | .605 | .067 | .645 | 8.99*** | |

| Extrinsic | .218 | .077 | .203 | 2.83** | |

| Step 2: Addition of Two-way Interaction | |||||

| Intrinsic × Extrinsic | −.118 | .024 | −.257 | −4.80*** | |

|

| |||||

| Need Fulfillment | Step 1: Main-Effects | ||||

| Intrinsic | .694 | .076 | .730 | 9.09*** | |

| Extrinsic | .050 | .088 | .046 | .57 | |

| Step 2: Addition of Two-way Interaction | |||||

| Intrinsic × Extrinsic | −.083 | .029 | −.178 | −2.86** | |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Models Predicting Relationship Outcomes: Covariance Approach

| Outcome | Model | B | SE B | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRQC | Step 1: Main-Effects | ||||

| Intrinsic: Ideals | −.013 | .152 | .005 | −.08 | |

| Extrinsic: Ideals | −.135 | .083 | −.100 | −1.62 | |

| Intrinsic: Perceptions | .640 | .074 | .631 | 8.65*** | |

| Extrinsic: Perceptions | .281 | .094 | .236 | 2.99** | |

| Step 2: Addition of Two-way Interaction | |||||

| Intrinsic × Extrinsic Perceptions | −.122 | .031 | −.230 | −3.93*** | |

|

| |||||

| Need Fulfillment | Step 1: Main-Effects | ||||

| Intrinsic: Ideals | .090 | .172 | .036 | .52 | |

| Extrinsic: Ideals | −.216 | .094 | −.157 | −2.28* | |

| Intrinsic: Perceptions | .694 | .084 | .674 | 8.27*** | |

| Extrinsic: Perceptions | .138 | .106 | .114 | 1.30 | |

| Step 2: Addition of Two-way Interaction | |||||

| Intrinsic × Extrinsic Perceptions | −.066 | .036 | −.123 | −1.83 | |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Hypothesis 3: Interaction between intrinsic and extrinsic ideals

The third hypothesis was that ideal dimensions would interact such that extrinsic ideals would largely become irrelevant to relationship quality once intrinsic ideals were met. Alternatively, extrinsic ideals would become relevant to relationship quality only when intrinsic ideals are not being met. Results revealed significant interactions between consistency on the intrinsic and extrinsic dimensions in three of the four models, with the final model marginally significant in the expected direction. As shown in Tables 2 and 3, the interaction was significant in predicting both relationship outcomes using the direct discrepancy approach, significant in predicting relationship quality in the covariance approach, and marginal in predicting need fulfillment in the covariance approach. The direction of the interactions consistently suggested that the extent to which one’s partner met one’s intrinsic ideals buffered the importance of whether one’s partner met one’s extrinsic ideals1–3.

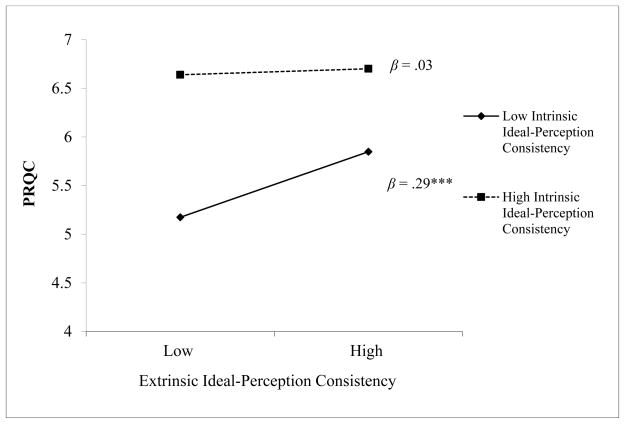

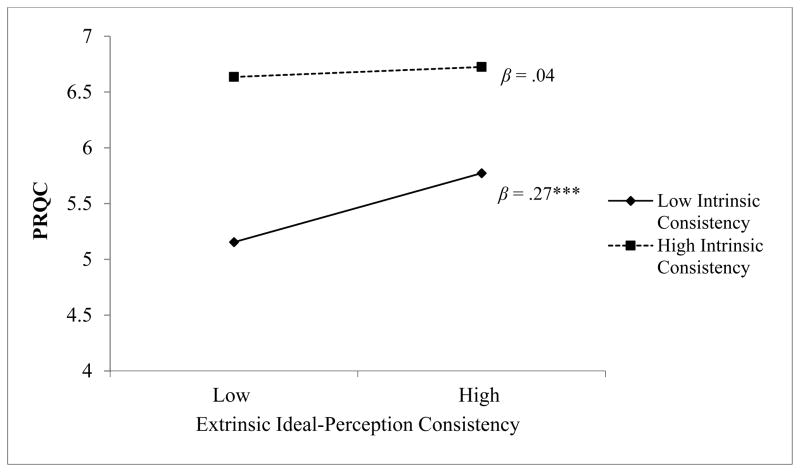

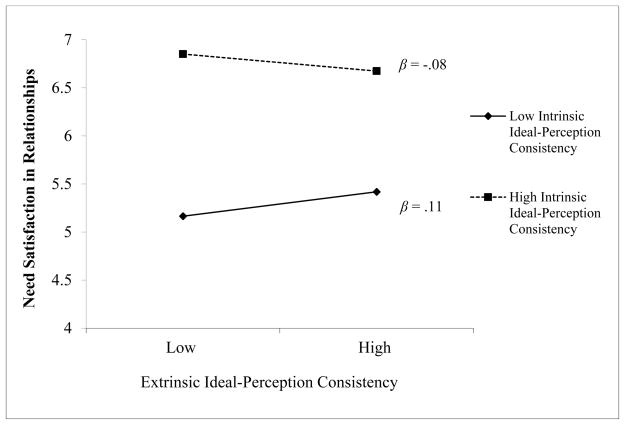

Graphs of all four interactions with results from tests of simple slopes are provided in Figures 1–4. Simple slopes were calculated according to procedures of Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken (2003) by deriving equations for the simple slopes of extrinsic ideal-perception consistency on relationship quality at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) intrinsic ideal-perception consistency. Figure 1 depicts levels of relationship quality as a function of ideal-perception consistency for both dimensions predicting the direct measure. As shown, at higher levels of intrinsic ideal-perception consistency, the effect of having extrinsic ideals met was not significant, β = .027, t(191) = .35, p = .727. At lower levels of intrinsic ideals being met, however, extrinsic ideal-perception consistency was associated with higher levels of relationship quality, β = .294, t(191) = 4.17, p < .001. The other three models showed consistent patterns. Figure 2 presents levels of relationship quality as a function of ideal-perception consistency for both dimensions using the indirect measure. As shown, at higher levels of intrinsic ideals being met, the association between having extrinsic ideals met and quality was not significant, β = .039, t(191) = .43, p = .670. At lower levels of intrinsic ideals being met, however, extrinsic ideal-perception consistency was associated with higher levels of relationship quality, β = .270, t(191) = 3.53, p < .001. Figure 3 presents levels of need satisfaction in relationships as a function of intrinsic and extrinsic ideal-perception consistency using the direct measure. In this case, having extrinsic ideals met did not predict need satisfaction at higher levels of intrinsic ideal-perception consistency, β = −.076, t(191) = −.85, p = .397, nor at lower levels of intrinsic ideal-perception consistency, β = .109, t(191) = 1.33, p = .185. Thus, meeting extrinsic ideals was irrelevant at both levels of having intrinsic ideals met. Overall, evidence suggests that meeting one’s partner’s ideals on intrinsic qualities buffered the extent to which extrinsic qualities predicted relationship quality.

Figure 1. Intrinsic x Extrinsic Dimension Interaction (Direct Approach) Predicting Relationship Quality.

*** p < .001

Figure 2. Intrinsic x Extrinsic Dimension Interaction (Covariance Approach) Predicting Relationship Quality.

*** p < .001

Figure 3. Intrinsic x Extrinsic Dimension Interaction (Direct Approach) Predicting Need Satisfaction in Relationships.

We also examined associations when extrinsic consistency was considered the moderator of the association between intrinsic consistency and relationship outcomes. We looked at simple slopes of intrinsic ideal-perception consistency at high and low levels of extrinsic consistency using the direct discrepancy approach. At higher levels of extrinsic ideal-perception consistency, having intrinsic ideals met was significantly associated with relationship quality, β = .372, t(191) = 4.20, p < .001, and need fulfillment, β = .541, t(191) = 5.27, p < .001. At lower levels of extrinsic ideal-perception consistency, having intrinsic ideals met was significantly associated with relationship quality, β = .640, t(191) = 9.41, p < .001, and need fulfillment, β = .726, t(191) = 9.21, p < .001. Results were identical using the indirect discrepancy approach. Overall, evidence suggests that meeting one’s partner’s ideals on intrinsic qualities was strongly associated with relationship outcomes both at higher and lower levels of extrinsic ideal-perception consistency.

Discussion

In an attempt to integrate the ISM with SDT, the current research evaluated the influence of different dimensions of ideal-perception discrepancy in predicting relationship outcomes. Are all ideals equally predictive of satisfying relationships? Our results suggest that not all ideals are equally predictive. Specifically, more intrinsic ideals, such as being warm, compassionate, and honest were found to be more strongly associated with satisfaction in relationships than relatively more extrinsic ideals such as being attractive or having resources. Additionally, when intrinsic ideals were met, extrinsic ideal-perception consistency was not important in predicting relationship quality.

The relative importance of satisfying intrinsic- over extrinsically-valued dimensions is consistent with the overarching theme of SDT. Indeed, our pilot data supported the notion that from an SDT perspective, intrinsic (relative to extrinsic) values are more likely to support the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and well-being because those values are more relevant to basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Sheldon et al., 2004). With regard to romantic relationships, prior work has shown that having more intrinsic (relative to extrinsic) reasons for being in one’s relationship predicts relative satisfaction after disagreements, less defensive and more understanding responses to conflict, and even more positive observed behaviors during a lab-induced conflict (Knee, Lonsbary, Canevello, & Patrick, 2005). Whereas these other studies examined the relative weighting of intrinsic and extrinsic values and reasons for being in one’s relationship (rather than their interaction), we began with the ISM assumption that perceiving that one’s partner meets one’s ideals generally predicts relationship satisfaction. In line with SDT, it appears that not all ideals are equally contributing to satisfaction.

Moreover, meeting extrinsic ideals is only important when intrinsic ideals are not met. This is in line with prior research on SDT, which suggests that when basic needs are not met, individuals may compensate with more extrinsic aspirations such as fame or wealth (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Kasser, Ryan, Zax, & Sameroff, 1995). According to the compensatory model, when people are in a need-thwarting environment, people start valuing extrinsic (hedonic) ideals (Kasser et al., 1995). Thus, people’s conceptualization of what is satisfying becomes more hedonic, and based on consistency between extrinsic perception and ideals. Indeed, the present findings reveal that, in relationships, satisfaction is more strongly tied to intrinsic ideal consistency. However, when partners and relationships do not match one’s intrinsic ideals, satisfaction is predicted by extrinsic ideal consistency. We also found it particularly interesting that such a compensatory interaction emerged for satisfaction but not for need fulfillment. From a self-determination theory framework, this makes sense, as satisfaction is a moving target, such that when needs are met, satisfaction is more of a eudaimonic concept, but when needs are not met, it is more hedonic. However, need fulfillment is always tied to intrinsic ideals, and cannot be compensated by consistency with extrinsic ideals.

Though not predicted, an interesting trend in the findings emerged when ideals and perceptions were entered separately (via the indirect method; Table 3). Stronger endorsement of extrinsic ideals predicted lower need fulfillment. This finding is consistent with research on self-determination theory, which has found that placing a higher importance on extrinsic aspirations (e.g., wealth, fame), is associated with lower well-being because it impedes the pursuit of intrinsic aspirations, which are closely tied to need fulfillment (Kasser & Ryan, 1993, 1996). In the current findings, by more strongly endorsing extrinsically driven characteristics, basic needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness go unmet. This work is the first to examine differences in intrinsic and extrinsic romantic partner ideals, and several future research avenues are evident.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The findings of this study should be considered in the light of several limitations, some of which can be pursued in future research. The use of undergraduate students and the primarily female sample limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should consider how ideals and perceptions operate in other populations. First, given previous research that ideals may vary across gender, it is possible that results might differ across gender. Further, conducting this research with a sample comprised of different levels of commitment (e.g., married couples) would be useful; for example, the ability to provide financial support might not be of concern to college daters but could be more important later in life. Additionally, a self-report study conducted at a single time is open to both the social desirability bias and restrictions to inferring the direction of causality. Utilizing cross-sectional data also prevents an evaluation of how the variables of interest and relationships among them change over time. Future research may examine how ideals, perceptions, and ideal-perception discrepancy change within-person over time. Further, it is possible that there is more measurement overlap between measures of intrinsic ideals and satisfaction than between extrinsic ideals and satisfaction. However, our results demonstrated similar results with all six subscales of the PRQC (see Footnote 1). Also, we evaluated ideal-perception discrepancy with two operationalizations. However, future research should investigate the nuances of each approach to facilitate establishment of an optimal method. Correlations between intrinsic and extrinsic measures were strong and positive. Whereas this may have occurred because some individuals have higher expectations (ideals) in general than do others, future research may evaluate how closely associated intrinsic and extrinsic attributes are in other types of relationships. Finally, the large proportion of females in our sample limits the generalizability of the findings. However, results from a recent meta-analysis suggested no gender differences for either physical attractiveness or earning prospects in their association with relationship evaluations (Eastwick et al., 2013).

Fletcher and colleagues (2004) examined ideals in short- versus long-term relationships. Their findings suggest that ideals have different levels of importance in short versus long-term relationships. Specifically, ideal standards declined in importance from long-term to short-term relationships (with the exception of attractiveness), suggesting that ideal standards are more important in long-term partnerships. Our research was limited to individuals who were already in committed romantic relationships. Although whether the relationship was perceived as short- versus long-term was not assessed, it was likely inclined toward long-term orientation. Future research may wish to investigate how different ideals and ideal-perception consistency operate in relationships that are not intended to be committed or long-term (e.g., hook-ups or friends with benefits).

An interesting line of future research may investigate individual differences in these associations. Based on the finding that endorsing higher extrinsic ideals predicted lower relationship outcomes, it seems worthwhile to consider whether certain types of individuals may be more likely to prefer extrinsic over intrinsic characteristics. A valuable future line of research may examine how personality variables (e.g., trait autonomy, narcissism) might influence ideals, perceptions, ideal-perception discrepancy, and the relational implications of such associations.

Finally, previous research has found support for the idea that the most satisfied dating and marital partners usually project the features of their ideal partners onto their own partners, effectively seeing in their partners the person they ideally wish to find (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 1996a). In a one-year longitudinal study involving dating couples, Murray et al. (1996b) found that relationships in which the partners idealized each other were more likely to remain stable, partners who idealized each other more early in the year tended to experience larger increases in satisfaction and larger decreases in relationship conflict and doubts by the end of the year, and over time, individuals gradually come to share their partners’ idealized images of themselves. Future research should compare the extent to which ideals affect perceptions to the extent to which perceptions affect ideals over time.

In closing, the current research is a first step in examining the differential importance of intrinsic and extrinsic partner and relationship characteristics. By integrating two conceptual and theoretical frameworks, the current research demonstrates that certain characteristics are more important in predicting relationship outcomes. Additionally, when intrinsic ideals were met, meeting extrinsic ideals no longer predicted relationship quality. Being an ideal partner may not be an attainable goal, but this research suggests that it is more important to meet one’s partner’s ideals on characteristics based on authenticity, intimacy, and closeness.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant F31AA020442.

Footnotes

Due to potential overlap between the intrinsic ideal/perception measures and the PRQC, ancillary analyses were run on the PRQC subscales (i.e., satisfaction, commitment, intimacy, passion, trust and love). Results with main effects of consistency on satisfaction revealed that whereas intrinsic ideal-perception consistency still significantly predicted satisfaction, extrinsic consistency was no longer a significant predictor. Interaction analyses indicated consistent results with PRQC using the direct approach, but the interaction with the indirect approach was no longer significant (p = .282). Main effects of consistency on passion indicated that the previously significant intrinsic consistency was no longer a significant predictor of passion using the direct approach (p = .287) nor the indirect approach (p = .124), whereas extrinsic consistency remained significant (p < .001 in both approaches). Interaction results, however, were consistent with PRQC. Main effects with trust replicated the significant effect of intrinsic consistency, but a significant negative effect of extrinsic consistency emerged (ps < .001 in both approaches), showing that trust decreased as a function of higher extrinsic ideal-perception consistency. The interaction was not significant in predicting trust with both discrepancy approaches. Results with commitment, intimacy, and love replicated the PRQC with the direct and covariance approaches.

Results were also run with the subscales of the need fulfillment measure (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness). Results with autonomy suggested that extrinsic consistency was not a significant predictor of autonomy support using either the direct or indirect discrepancy approach (ps = .664 and .524, respectively). The interactions were consistent with the overall measure, however. Regarding fulfillment of competence needs, extrinsic consistency was a marginal predictor using the direct approach (p = .067) and was not a significant predictor using the covariance approach (p = .132). The intrinsic-extrinsic consistency interaction was not significant using the direct approach (p = .197) nor with the indirect approach (p = .678). Finally, results with relatedness did not show a significant effect of extrinsic consistency (ps = .431 and .257), but the interactions were consistent with the need fulfillment composite measure.

Results were performed with the extrinsic ideals and perceptions separately for attractiveness, status, and passion. Results were identical in size and pattern to when utilized together as extrinsic (ps < .001 for all interactions and with both approaches to discrepancy).

References

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:497–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Schmitt DP. Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review. 1993;100:204–232. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LJ, Simpson JA, Kashy DA, Fletcher GL. Ideal standards, the self, and flexibility of ideals in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:447–462. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL. The psychology of self-determination. Lexington, MA: Heath; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In: Deinstiber R, editor. Nebraska symposium on motivation: Perspectives on motivation. Vol. 38. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1991. pp. 237–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM, Gagné M, Leone DR, Usunov J, Kornazheva BP. Need satisfaction, motivation, and well-being in the work organizations of a former Eastern bloc country: A cross-cultural study of self-determination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:930–942. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of Research in Personality. 1985;19:109–134. [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human need and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry. 2000;11:227–268. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick PW, Neff L. Do ideal partner preferences predict divorce? A tale of two metrics. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2012;6:667–674. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwick PW, Luchies LB, Finkel EJ, Hunt LL. The predictive validity of ideal partner preferences: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0032432. published online in advance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Thomas G. Ideals, perceptions, and evaluations in early relationship development. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000a;79:933–940. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.6.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Thomas G. The measurement of perceived relationship quality components: A confirmatory factor analytic approach. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000b;26:340–354. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA, Thomas G, Giles L. Ideals in intimate relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:72–89. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfriend W, Agnew CR. Sunk costs and desired plans: Examining different types of investments in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34:1639–1652. doi: 10.1177/0146167208323743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin D, Murray S, Gonzalez R. Difference score correlations in relationship research: A conceptual primer. Personal Relationships. 1999;6:505–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6811.1999.tb00206.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM. A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:410–422. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM. Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Kasser T, Ryan RM, Zax M, Sameroff AJ. The relations of maternal and social environments to late adolescents’ materialistic and prosocial values. Developmental Psychology. 1995;31:907–914. [Google Scholar]

- Knee C, Lonsbary C, Canevello A, Patrick H. Self-determination and conflict in romantic relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:997–1009. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.6.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knee CR, Nanayakkara A, Vietor NA, Neighbors C, Patrick H. Implicit theories of relationships: Who cares if romantic partners are less than ideal? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:808–819. [Google Scholar]

- La Guardia JG, Ryan RM, Couchman CE, Deci EL. Within-person variation in security of attachment: A self-determination theory perspective on attachment, need fulfillment, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:367–384. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller AC, Deci EL, Elliot AJ. Person-level relatedness and the incremental value of relating. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36:754–767. doi: 10.1177/0146167210371622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. The benefits of positive illusions: Idealization and the construction of satisfaction in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996a;70:79–98. [Google Scholar]

- Murray SL, Holmes JG, Griffin DW. The self-fulfilling nature of positive illusions in romantic relationship: Love is not blind, but prescient. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996b;71:1155–1180. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.71.6.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJO, Simpson JA. Regulation processes in intimate relationships: The role of ideal standards. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:662–685. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick HH, Knee CR, Canevello AA, Lonsbary CC. The role of need fulfillment in relationship functioning and well-being: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:434–457. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Patrick BC. Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1996. Attachment and intimacy: Component processes; pp. 523–563. [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, Sheldon KM, Gable SL, Roscoe J, Ryan RM. Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:419–435. doi: 10.1177/0146167200266002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Sheldon KM, Kasser T, Deci EL. All goals are not created equal: An organismic perspective on the nature of goals and their regulation. In: Gollwitzer PM, Bargh JA, editors. The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 1996. pp. 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Chirkov VI, Little TD, Sheldon KM, Timoshina E, Deci EL. The American Dream in Russia: Extrinsic aspirations and well-being in two cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1509–1524. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman C, Fazio RH, Zanna MP. Effects of salience of extrinsic rewards on liking and loving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1980;38:453–460. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.38.3.453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Ryan RM, Deci EL, Kasser X. The independent effects of goal contents and motives on well-being: It’s both what you pursue and why you pursue it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30:475–486. doi: 10.1177/0146167203261883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uysal A, Lin H, Knee C, Bush AL. The association between self-concealment from one’s partner and relationship well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2012;38:39–51. doi: 10.1177/0146167211429331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]