Abstract

Physicians are required to advocate for and counsel patients based on the best science and the interests of the individual while avoiding discrimination, ensuring equal access to health and mental services. Nonetheless, the communication gap between physician and patients has long been observed. To this end, the Institute for the Public Understanding of Health and Medicine of the Rutgers University New Jersey Medical School has expanded its efforts. This report describes two new programs: a legacy lecture series for medical students and an international “experience”, in Huancayo, Peru, for medical students and faculty. The MiniMed outreach program, now in its ninth year and first described in this journal in 2012, was designed to empower the powerless to communicate more effectively with clinicians, thus improving both the effectiveness of the physician–patient relationship and health care outcomes. The approach of the two new programs and their effects on patients, particularly the underserved, and medical students and faculty, are outlined in the following article.

Keywords: MiniMed program, equal access, underserved populations, Newark Renaissance House, Kintock Group, role modeling

Background

The communication gap between patients and their physicians has long been observed,1–3 as has its negative consequences.4 Sociopolitical changes in the last several decades have effected significant shifts in the ethical imperatives associated with the physician–patient relationship. Moral and value decisions can no longer be made solely by physicians on behalf of their patients. Today’s physician must be adept at dealing with ethical conflicts and reconciling his own beliefs with those of his patient. Pellegrino notes that “… the ancient precept, primum non nocere, must now apply to the integrity of the patient’s value system as well as his body.”3 Furthermore, physicians must be open to discussing moral choices with patients. Medicine’s traditional moral authority is no longer universally accepted. Thus, it is imperative that medical educators help succeeding generations of physicians adapt to these changes, and promote the interests of the patient regardless of financial circumstances, socioeconomic status, or the health care setting.5 Physicians must continue to advocate for and counsel each patient based on the best scientific knowledge available and the interests of the individual, and work to eliminate discrimination, thus ensuring patients’ equal access to health and mental health services in the community.5,6 As an example, physicians practicing in prison setting have certain ethical imperatives, especially in view of their role as agents of both the prisoner and the correctional system, but should nevertheless strive to base their medical judgments on providing appropriate care for the individual.5

Allowing medical students to teach the underserved can help reinforce these values. Medical students often invest time and effort into activities that will offer them the highest yield in terms of income and prestige. Devoting time to courses on medical ethics does not often fit their perceived requirements.7 Disparities in health care can begin to be addressed by having students work with minority and disadvantaged populations. The American College of Physicians is on record as advocating

…increased resources for identifying and implementing educational approaches and behavior change strategies designed for minority audiences and the providers who treat them.8

Affording medical students the opportunity to teach and interact with culturally, economically, and socially removed social groups, in nonthreatening contexts can promote empathy, a critical variable in the ethical delivery of health care.

This report describes the expansion of the efforts of the Institute for the Public Understanding of Health and Medicine of the Rutgers University New Jersey Medical School (NJMS), first reviewed in this journal by Lindenthal and DeLisa.9 Since the publication of the original paper, two programs have been added: a legacy lecture series for medical students and an international “work experience”, in Huancayo, Peru, for medical students and members of the faculty. This report further describes our outreach programs, now in their ninth year.

Rutgers NJMS approach

To enable our students to fulfill the aforementioned ethical imperatives, we expanded our MiniMed program. It now includes educational programs for groups outside of our school who would otherwise be unable to participate in the traditional MiniMed school. Medical students now prepare and deliver lectures during the academic year, to male and female inmates lodged at Kintock Group facilities and to residents of the Newark Renaissance House. A portion of the final session is devoted to a discussion of community health facilities, and a copy of each PowerPoint presentation is provided to attendees, as is a list of area health clinics. Administrative tasks, including arrangements for attendance of residents and inmates, are the responsibility of the responsibility of Kintock Group and Newark Renaissance House administrators. Medical students and administrators determine lecture topics.

Outreach programs

Newark Renaissance House

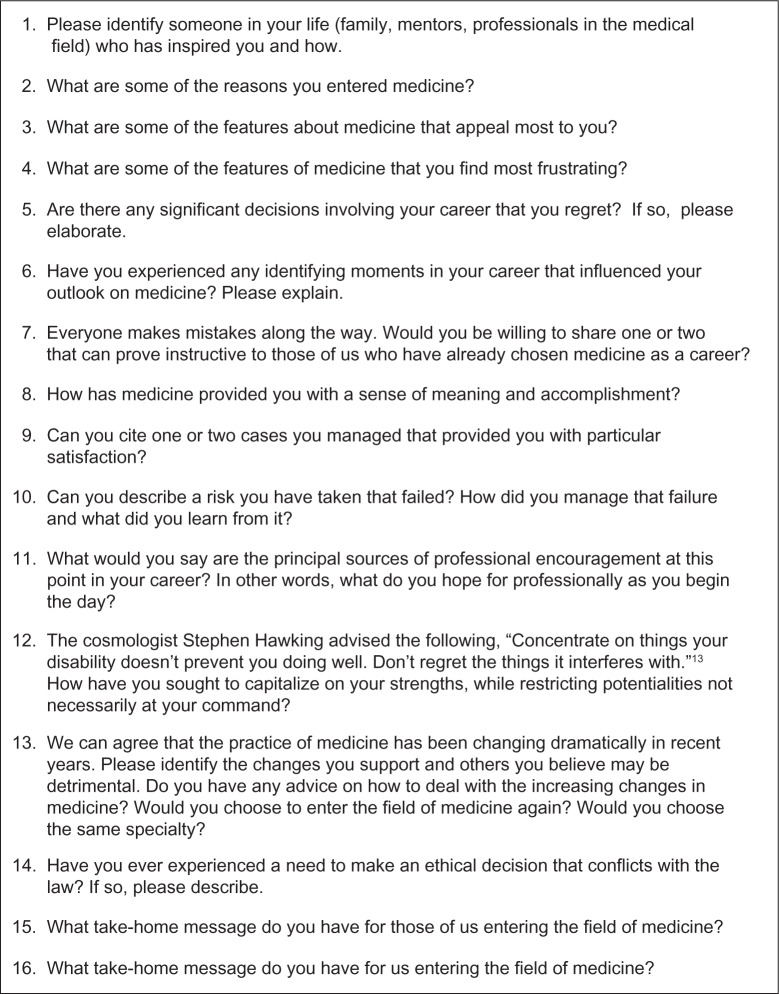

The Newark Renaissance House was established in 1975 as a nonprofit residential therapeutic community with a focus on chemically dependent women and children, who are among the least empowered members of our society. The programs offered at the Newark Renaissance House serve the drug therapy needs of infants, children, adolescents, women, and men, and fall under the jurisdiction of the New Jersey Division of Child Protection and Permanency Service, as well as the Division of Mental Health and Addiction Services. Since its founding, programs have been added to address the spread of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Clients usually remain in residence between 6 and 8 months. Programs currently serve the drug therapy needs of infants, children, adolescents, women, and men. Medical students working in the Rutgers NJMS outreach program provide 16 60-minute lectures to the 38 clients enrolled in the adolescent residential program, for young men between the ages of 15 and 17, as well as to the 23 clients in the women and children’s residential program devoted to the substance abuse needs of pregnant women and their children. Figure 1 provides a sample of recent lectures provided to the female residents of Renaissance House and male adolescents.

Figure 1.

Sample of lectures provided to residents of Newark Renaissance House and the Kintock Group.

The Kintock Group

With the United States harboring more prisoners than any other nation, affording medical students with the opportunity to instruct inmates in this setting is very useful. In operation since 1985, the Kintock Group is a nonprofit organization under contract with the Federal Bureau of Prisons, the New Jersey State Parole Board, and the Department of Corrections. In addition to the program in Newark, NJ, there are two more Kintock Group programs operating in Bridgeton and in Paterson, NJ, and another in Philadelphia, PA. While each establishment has its own set of programs, the mission of all is the same – to serve as a conduit between prison and release into the community by preparing individuals to care for themselves, to practice responsible behavior, and to enter the workforce. Medical students are involved in educating 100 of the 400 residents, referred to as “parolees”, in the final phase of their incarceration. About 10% of the resident population is female. The average length of stay varies between 3 and 6 months. See Figure 1 for a sample of the lectures given to inmates.

MiniMed International

Increasing immigration from Latin American countries has motivated us to join other medical schools in providing learning experiences for our medical students in the southern hemisphere. We formed a novel program, involving both students and faculty members, within the last 3 years. The program was launched in collaboration with medical colleagues in Huancayo, Peru, the capitol of the Junin province with a population of 38,000, and with a well-established civic organization known as Chusi Wanka. The program affords Rutgers NJMS students with a 4-week health-related work experience between their first and second year of medical school. This effort provides an outstanding opportunity for medical students to learn the rudiments of health care delivery in an emerging country burdened with many preventable diseases. This is accomplished by having our medical students shadow clinicians and participate in “rounding” at the Daniel Alcides Carrión and EsSalud Hospitals, and by attending lectures at the Escuela de Medicina de la Universidad Nacional del Centro del Peru. As well, the Medical students participate in other activities – they teach young children in “HIV orphanages” about the basics of good health and disease prevention, assist their Peruvian medical student peers in learning English, and provide health-related lectures to the citizens of Huancayo.

Plans are underway to introduce a research component into the medical student experience in Peru, with faculty participation from both Peru and the United States. Paterson, NJ, about 18 miles from Newark, has a large Peruvian population, potentially allowing for comparative analyses.

With the second phase of this program, members of our faculty travel to Huancayo during the academic year to perform medical and surgical rounds, provide a week-long series of lectures to residents, and offer medical consultations. This program has proved refreshing to both our Peruvian colleagues as well as to our seasoned clinicians. Traveling with us is a librarian, whose lectures address accessing evidence-based medical information from the Internet. Participating faculty have found the experience valuable. Figure 2 provides a list of recent lectures presented by faculty members in Huancayo.

Figure 2.

Sample of lectures presented to medical faculty and medical students in Peru, by faculty in Huancayo, Peru.

Rationale

By providing medical students, early in their training, with opportunities to communicate with diverse underserved populations in the role of instructor, we are attempting to raise perceptions, while imparting the rudiments of health education. The classroom provides a milieu conducive to breaking down of barriers to communication. Medical students learn to appreciate “where their audience is coming from” and more specifically, lay students’ attributes and challenges, and their own mistaken perceptions and projections, while the route to becoming a physician is gradually elucidated. One commonly hears medical students reflecting on the intelligence, the fund of knowledge, and sophistication regarding health-related matters of the homeless, inmates, and wayward adolescents. This experience can help demystify many misconceptions, for eg, how the inmates became estranged from society. Medical students also learn about the strategies employed by drug abusers as they seek to satisfy their addiction – stunned silence followed after one medical student asked a prisoner how she was able to afford her alcohol addiction, and she revealed that she would crack open and drink the alcohol contents of cans of hairspray purchased for $0.99. Medical students were astounded to learn that a woman incarcerated for “vagrancy” derived from an advantaged social classes and that prisoners can have siblings who are professors in medical schools.

A century ago, sociologist Charles Horton Cooley described the “looking glass self,” arguing that individuals’ self-conception derives from how they believe others view them.10 Interacting in nonthreatening academic settings on the “home turf” of the individual challenges all concerned to reevaluate their self-concepts and, hopefully, encourages empathy, a significant ingredient in enhancing the efficacy of clinical care.

Our experience with these outreach programs has demonstrated their importance in exposing medical students to diverse populations as well as in instructing them in the art of teaching. The thought of being charged with educating these groups is daunting at first to students, but after several weeks, comfort and confidence levels rise greatly in the medical students and their students. Over time, medical students begin to empathize with their audiences by virtue of the latter’s eagerness to learn and the personal experience they bring to the sessions. By the end of the semester, members of each group view one another with heightened respect and with the appreciation that they still have much to learn from one another. We suspect that this experience will help fortify future clinicians who will be charged with patients from increasingly diverse backgrounds.

Role modeling with legacy lectures

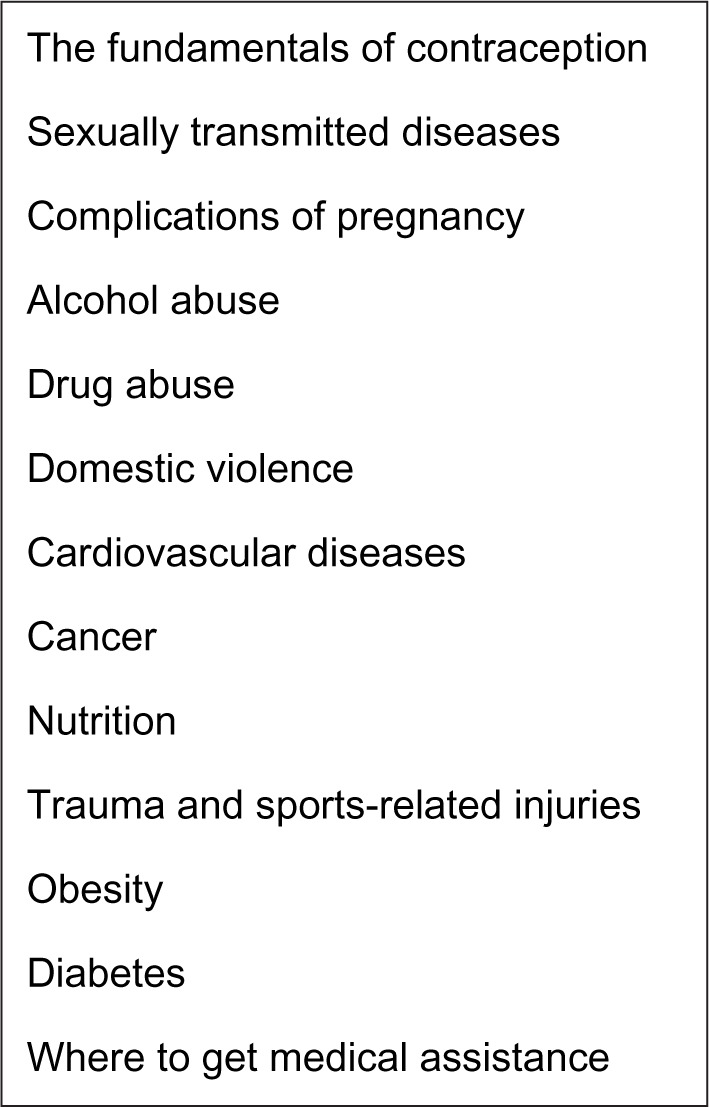

Role modeling is an inherent component of education and the design of the Institute for the Public Understanding of Health and Medicine. The 50 preceptors in our in-house programs, their 18 peers in the outreach programs, and the ten new medical students per year involved in MiniMed International are required to attend several legacy lectures annually provided by senior faculty members. Legacy lecturers are drawn by the medical students from among senior members of the Rutgers NJMS faculty, whose careers span 25 years; the objective is to deliver an informal discourse describing some of the many challenges posed by a lifetime career in health and medicine. The central theme of the legacy lectures focuses on both personal and professional life experiences. Lecturers are given an opportunity to reflect candidly on missed opportunities and those pursued with success, mistakes that should have been avoided and mistakes from which they learned from, recognition deemed appropriate and other activities unrequited, and the management of failure, as well as additional experiences of the lecturer’s choosing. The legacy lecturer is provided with a standardized series of questions at least 2 months in advance to facilitate adequate reflection (Figure 3). A medical student moderates the 75-minute session.

Figure 3.

Questions provided to legacy lecturers.

Conclusion

The mantra of our MiniMed School is that an educated patient is the doctor’s best friend. Medical ethics demand an inclusive orientation directed to all citizens. Medical students are empowered by the outreach programs, as they are nonthreatening in nature. These programs are not meant to supplant health delivery experiences, such as screening clinics, but rather, to augment them. Recent empirical evidence suggests that physicians are more likely to adopt a patient-centered style of communication when they have had increased interactions with patients who ask questions, seek information, and express their concerns.11 How beneficial this approach will be in terms of health care outcomes is yet to be determined. Patients will need to know more about health owing to the changing health care landscape in the country. Empowering the powerless to communicate more intelligently and more effectively with clinicians should help increase both the efficiency and efficacy of the physician–patient encounter.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Evans HM. Do patients have duties? J Med Ethics. 2007;33(12):689–694. doi: 10.1136/jme.2007.021188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Physicians Racial and ethnic disparities in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:226–232. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brody DS. The patient’s role in clinical decision-making. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93(5):718–722. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-5-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pellegrino ED. Editorial: Medical ethics, education, and the physician’s image. JAMA. 1976;235(10):1043–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B, Steinwachs D, Morris I, Bause G, Siebert S, Westin C. Patient-doctor agreement about problems needing follow-up visit. JAMA. 1979;242(4):344–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snyder L, Leffler C, Ethics and Human Rights Committee, American College of Physicians Ethics manual: fifth edition. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(7):560–582. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-7-200504050-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Povar GJ, Blumen H, Daniel J, et al. Medicine as a Profession Managed Care Ethics Working Group Ethics in practice: managed care and the changing health care environment: medicine as a profession managed care ethics working group statement. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(2):131–136. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-2-200407200-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barber B. Compassion in medicine: toward new definitions and new institutions. N Engl J Med. 1976;295(17):939–943. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197610212951707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindenthal JJ, Delisa JA. Promoting appreciation of the study and practice of medicine: inner workings of a Mini-Med program. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2012;3:73–78. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S30495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groman R, Ginsburg J, American College of Physicians Racial and ethnic disparities in health care: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):226–232. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-3-200408030-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooley CH. On Self and Social Organization. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cegala DJ, Post DM. The impact of patients’ participation on physicians’ patient-centered communication. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77(2):202–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreifus C. Life and the Cosmos Word by Painstaking Word. New York Times. May 10, 2011. [Accessed on February 10, 2015]. p. D1. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/10/science/10hawking.html.