Significance

Bismuth compounds have long been used in clinic for the treatment of various diseases, in particular, for Helicobacter pylori infection. We reported the mechanism of uptake of bismuth compounds by mammalian cells and bacteria, and demonstrated a passive transport of the metallodrug. We showed that glutathione and multidrug resistance protein transporter mediate a self-propelled disposal of bismuth antiulcer drug. A model was derived to elucidate the uptake of the metallodrug, and which may readily be extended to other drugs or drug candidates. Our work uncovered the secret of low toxicity of bismuth in human and relatively high drug selectivity against “glutathione-poor” pathogens such as H. pylori.

Keywords: bismuth, drug selectivity, glutathione, MRP, positive feedback

Abstract

Glutathione and multidrug resistance protein (MRP) play an important role on the metabolism of a variety of drugs. Bismuth drugs have been used to treat gastrointestinal disorder and Helicobacter pylori infection for decades without exerting acute toxicity. They were found to interact with a wide variety of biomolecules, but the major metabolic pathway remains unknown. For the first time (to our knowledge), we systematically and quantitatively studied the metabolism of bismuth in human cells. Our data demonstrated that over 90% of bismuth was passively absorbed, conjugated to glutathione, and transported into vesicles by MRP transporter. Mathematical modeling of the system reveals an interesting phenomenon. Passively absorbed bismuth consumes intracellular glutathione, which therefore activates de novo biosynthesis of glutathione. Reciprocally, sequestration by glutathione facilitates the passive uptake of bismuth and thus completes a self-sustaining positive feedback circle. This mechanism robustly removes bismuth from both intra- and extracellular space, protecting critical systems of human body from acute toxicity. It elucidates the selectivity of bismuth drugs between human and pathogens that lack of glutathione, such as Helicobacter pylori, opening new horizons for further drug development.

Bismuth (Bi) compounds have been used in clinical medicine for over a century in various infectious diseases (1–4). Together with antibiotics, bismuth drugs such as bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol) and colloidal bismuth subcitrate (CBS; De-Nol) are used to treat Helicobacter pylori infection and gastrointestinal disorder (5–7). Interestingly, bismuth drugs rarely exert acute toxicity in human but instead mitigate other drugs’ toxicity (8). This drug selectivity between human and certain pathogens has been well observed yet poorly understood. Because bismuth is a heavy metal, its disposal in human cells becomes the key of this conundrum.

Low uptake of bismuth by human gastrointestinal tract (GIT) was often considered as the reason of bismuth’s low toxicity (1). However, it contradicted the fact that no severe toxicity appeared, even when bismuth was repeatedly injected intramuscularly to treat syphilis (9). Furthermore, even at very extreme doses or physical conditions, bismuth only causes reversible nephropathy or encephalopathy (10, 11). And last, over 90% of absorbed bismuth was found metabolized into bismuth–sulfur particles (12). These particles were exclusively located in subcellular vesicles of a variety of organs (e.g., kidney, liver, brain, and testicle), which is indicative of a universal disposal mechanism at cellular level (12–14).

Based on the hard–soft acid-base concept, Bi3+ is a borderline metal ion. It exhibits high affinity toward many biological thiols (15–17). Glutathione (GSH) and metallothionein are the two key thiols of bismuth pharmacology in mammalian cells (15, 18). Bismuth was found to induce metallothionein expression in renal proximal tubules; however, only a small portion of bismuth was actually bound to it (8, 19). Bismuth also affected glutathione metabolism in different types of cells. It caused an exponential decay on 1H NMR signal of glutathione in human red blood cells and a hepatobiliary coexcretion of bismuth and glutathione in rodents (18, 20). However, the origin of sulfur in bismuth–sulfur particles in mammalian cells remains unknown. It is interesting to note that neither glutathione nor metallothionein exists in H. pylori; cysteine is the major thiol (21). Cysteine-rich proteins with high binding affinity to bismuth have also been identified (22). Unlike in mammalian cells, bismuth caused severe cell vacuolation, degradation, and death in H. pylori (12, 23, 24).

Previously, we have studied the formation of Bi3+–glutathione complex [Bi(GS)3] both in vitro and in vivo (18). We found that the complex is thermodynamically stable yet kinetically labile, with the exchange rate of Bi3+ between glutathione molecules of ∼1,500 s−1 at pH 7.4. Because Bi3+ exhibits higher affinity with metallothionein than with glutathione, metallothionein seems to be a better choice for Bi3+ ions. However, glutathione has its advantages. Its conjugates can be swiftly transported through multiple transporters, which mainly belong to the multidrug resistance protein/cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (MRP/CFTR) family in human cells (e.g., MRP1) (25, 26). And with 63% sequence similarity to human MRP1, Ycf1p was found to transport multiple metal–glutathione conjugates (As3+, Cd2+, Hg2+) into yeast vacuoles (27, 28). MRP1 was also found on subcellular vesicles, conferring drug resistance to doxorubicin (29).

In this report, we demonstrate that most bismuth was passively absorbed, sequestrated by glutathione and MRP transporter in human cells. We propose a quantitative mathematical model based directly on these biochemical facts, i.e., sequestration-aided passive transport (SAPT) model. We present explicit mathematical solution for the model as a function of parameters, which can explain the mechanism behind the pattern of bismuth uptake. It describes a self-propelled system of bismuth disposal and reveals detailed information about cell permeability of bismuth and glutathione level when the time and dose of bismuth treatment were varied.

Results

Bismuth Uptake is a Biphasic and Glutathione-Consuming Process.

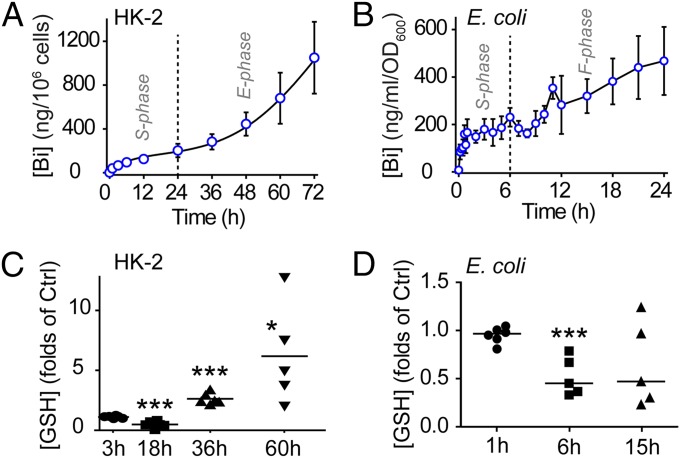

Bi3+ compounds have been used to treat gastrointestinal infection for decades. However, its mode of uptake remains unclear. We determined intracellular bismuth levels in human proximal tubular cells HK-2 and Escherichia coli treated with 0.5 mM CBS using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). We found that bismuth uptake curves of both cells exhibited two distinctive phases (Fig. 1 A and B). The first phases in both cells (first 24 h for HK-2 cells and first 6 h for E. coli cells) exhibited a pattern of saturation that fits the profile of passive transport. The second phases exhibited a pattern of exponential growth in HK-2 cells, whereas there was a pattern of fluctuation in E. coli. In the meantime, we determined the intracellular levels of glutathione using a glutathione assay. We found that during the saturating phase, bismuth uptake consumes a large portion of intracellular glutathione in both HK-2 cells and E. coli (∼50%; Fig. 1 C and D). During exponential phase, glutathione levels in HK-2 cells increased to over fourfold the original level (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Time-dependent bismuth uptake and glutathione level changes in HK-2 and Escherichia coli cells treated with 0.5 mM CBS. (A) Bismuth uptake in HK-2 exhibits a saturating (S phase) and an exponential growing pattern (E phase). (B) Bismuth uptake in E. coli exhibits a saturating (S phase) and a fluctuating pattern (F phase). (C) Glutathione level was significantly reduced (18 h) and increased (36 and 60 h) in CBS-treated HK-2. (***P = 0.0003, ***P < 0.0001, and *P = 0.0149, respectively). (D) Glutathione level was significantly reduced (6 h) in CBS-treated E. coli. (***P = 0.0009). The reduction of glutathione at 15 h is statistically insignificant.

Bismuth Uptake is Mainly a Process of Passive Transport.

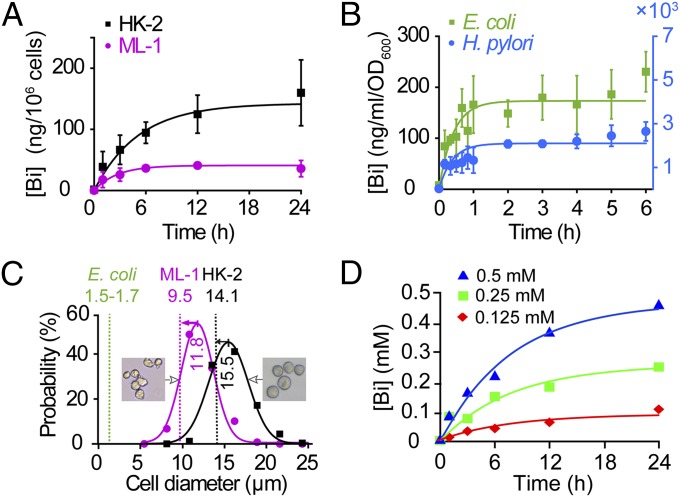

To further investigate the mode of bismuth uptake, both human cell lines (HK-2 and ML-1) and bacterial cells (E. coli and H. pylori) were used for in-depth examination on the saturating phase of bismuth uptake. The time-dependent bismuth uptake curves of all these cells (24 h for human cells, 6 h for bacterial cells) exhibited a saturating pattern, suggesting a process of passive transport (Fig. 2 A and B). To analyze the data quantitatively, we derived a model of passive transport based on Fick’s law (30). The mathematical equation can be expressed below (Supporting Information):

| [1] |

where j(t) is the amount of bismuth in cells at time t, jmax is the upper limit of bismuth uptake and P is the overall bismuth permeability (h−1) of the cell. Eq. 1 defines a curve starting from the origin and saturating at a specific time, in which jmax and P determined the amplitude and time of saturation respectively (Fig. S1A).

Fig. 2.

Bismuth uptake is a process of passive transport. Human and bacterial cells were treated with 0.5 mM CBS for 0–24 and 0–6 h, respectively. All data were fitted with Eq. 1. Bismuth uptake in (A) human cell lines HK-2 and ML-1 and (B) E. coli and H. pylori all exhibited a saturating pattern. (C) Comparison ESD of E. coli, ML-1 and HK-2 obtained from the fitting of A and B (dashed lines) to the diameter distributions of ML-1 and HK-2 obtained from microscopic imaging (bell shape curves; for details, see Fig. S2). (D) Bismuth uptake in HK-2 incubated with 0.5, 0.25, and 0.125 mM CBS. All cells were pretreated with 0.5 mM l-BSO for 24 h to deplete glutathione. The unit of bismuth levels was converted to mM using cell diameter obtained in C.

By fitting the data of bismuth uptake with Eq. 1, we found that P values of bacterial cells are 2.61 ± 0.78 h−1 for H. pylori and 2.43 ± 0.42 h−1 for E. coli, one order of magnitudes larger than those of human cells (0.20 ± 0.12 h−1 for HK-2 and 0.38 ± 0.18 h−1 for ML-1 cells) (Fig. 2 A and B). These data indicate that the overall permeability (P) is reversely correlated with cell diameters, which concurred with our mathematical characterization of passive transport (Fig. S1B and Table S1).

Curve fitting also generated the values of jmax, which help us to calculate the volumes of all these cells (v = jmax/c). For comparison, cell volumes were converted to their equivalent spherical diameters [ESD = (6v/π)1/3, is the diameter of a sphere that with the same volume to a cell]. The ESDs of ML-1 and HK-2 cells calculated from curve fitting are 9.5 ± 2.6 and 14.1 ± 5.6 μm, which are comparable to the values of those measured by microscopy (11.8 ± 0.1 for ML-1 and 15.5 ± 0.2 µm for HK-2) (Fig. 2C, Fig. S2). Furthermore, given the number of E. coli to be 5 × 108 - 109 cells/mL/OD600, calculated ESD of E. coli ranges from 1.5 ± 0.6 to 1.8 ± 0.7 μm, which concords previously reported values (31).

To avoid the potential interference of glutathione in bismuth uptake, HK-2 cells were first treated with 0.5 mM l-buthionine-sulfoximine (l-BSO) for 24 h to deplete GSH. These cells were then treated with 0.125, 0.25, and 0.5 mM CBS to yield time-dependent bismuth uptake curves (Fig. 2D). Using the diameter of HK-2 cells generated by microscopy (15.5 ± 0.2 µm), the amounts of bismuth absorbed were transferred into the intracellular bismuth levels. Fitting of these data with Eq. 1 generated their jmax values as 0.13 ± 0.02, 0.24 ± 0.03, and 0.42 ± 0.03 mM, which are comparable to the corresponding CBS concentrations in medium (Fig. 2D). Based on above data, we concluded that the uptake of CBS is mainly a process of passive transport when the concentration of CBS is between 0.1 and 1 mM.

Glutathione Is Critical for Bismuth Uptake and Detoxification.

We found that the uptake of CBS (Eq. 1) and consumption of GSH (Eq. S5) in human cells shares a similar mathematical expression (Supporting Information). Moreover, the permeability (P) of CBS uptake in HK-2 and ML-1 cells (0.20 ± 0.12 and 0.38 ± 0.18 h−1; Fig. 2A) are also comparable to the rate constant (k) of GSH consumption (0.20 ± 0.04 h−1) in CBS-treated red blood cells (18), which result in comparable half-lives of bismuth uptake and glutathione consumption.

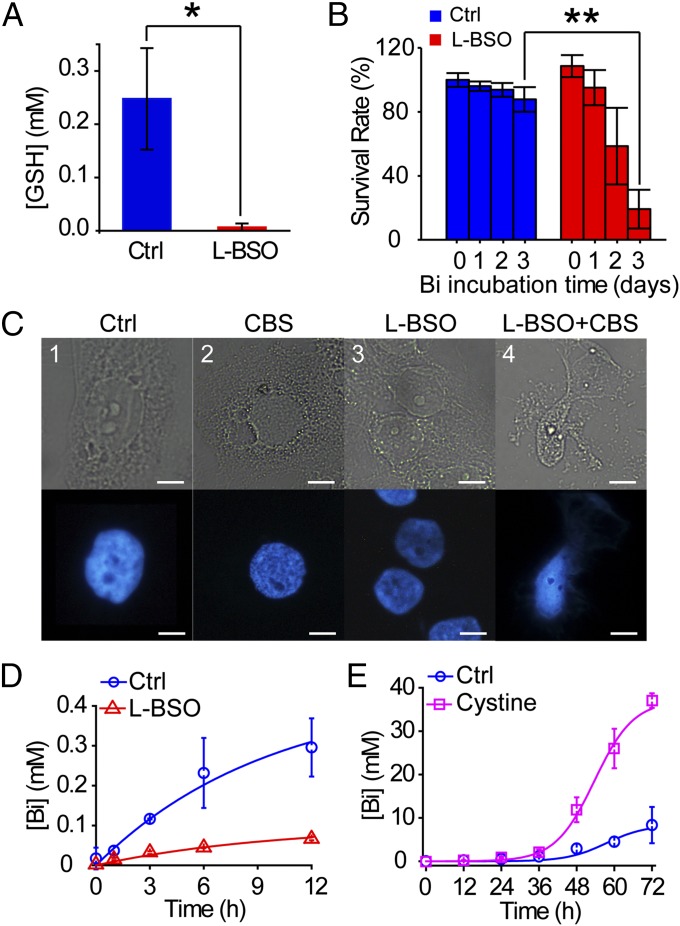

To investigate the role of glutathione in bismuth metabolism, we examined the toxicity and uptake of bismuth in human cells with or without glutathione depletion. Incubation of HK-2 with 0.5 mM l-BSO for 24 h successfully depleted the glutathione (Fig. 3A). Treating HK-2 with 0.5 mM CBS for 72 h exhibited no toxicity, in contrast, the survival rate of l-BSO–pretreated HK-2 dropped to only 20% (Fig. 3B). Survival rates of other human cells to CBS insult were also reduced by 40–60% upon l-BSO treatment (Fig. S3). Meanwhile, l-BSO–treated HK-2 (0.5 mM for 24 h) developed severe cell degradation and nucleus malformation upon CBS stress (0.5 mM for 36 h) (Fig. 3C, 4). These data concluded the indispensability of glutathione in Bi detoxification.

Fig. 3.

Glutathione is critical for bismuth detoxification and uptake in human cells. (A) l-BSO (0.5 mM for 24 h) depleted glutathione from HK-2 cells. (*P = 0.0163). (B) l-BSO reduced the survival rate of HK-2 treated with 0.5 mM CBS. (**P = 0.0012). (C) Morphology and Hoechst staining of HK-2 treated with (1) medium, (2) 0.5 mM CBS for 36 h, (3) l-BSO, and (4) l-BSO and then CBS. HK-2 of (1–3) appeared normally. l-BSO plus CBS-treated HK-2 developed severe cell degradation and nucleus malformation (4). Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Bismuth uptake in HK-2 treated with 0.05 mM CBS for 0–12 h, with or without l-BSO pretreatment. (E) Bismuth uptake in HK-2 treated with 0.5 mM CBS for 0–72 h, with or without cystine supplement (∼0.1 mg/mL).

Fig. 4.

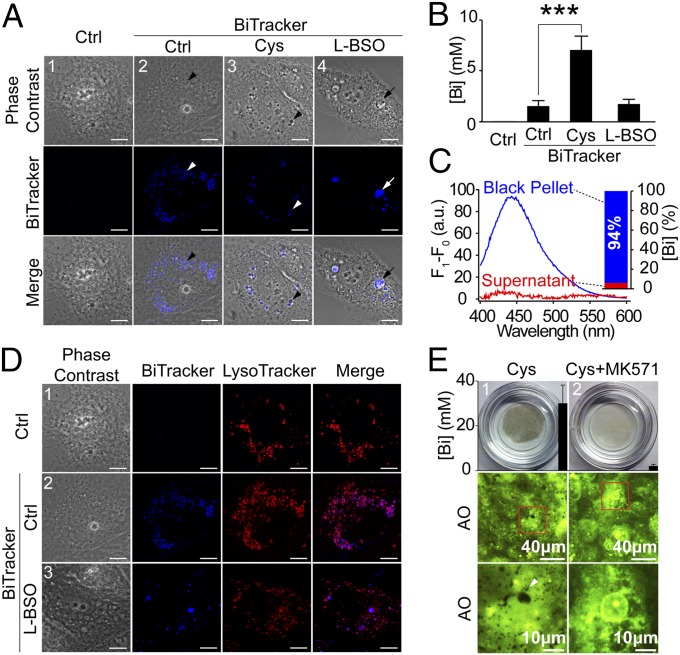

Glutathione and MRP transporter mediated bismuth compartmentalization. Location of bismuth was labeled using a BiTracker (blue fluorescence). (A) Confocal microscopic images of BiTracker-treated HK-2 cells (50 μΜ for 36 h). The cells were treated with (1) control, (2) BiTracker, (3) BiTracker with cystine supplement (∼0.1 mg/mL), and (4) 0.5 mM l-BSO for 24 h and then BiTracker. In HK-2 of (2–3), the BiTracker exclusively located inside vesicles contains black particles (arrow head), cystine supplement enlarged these vesicles. In l-BSO–treated HK-2 (4), cells developed severe vacuolation with blue fluorescence inside vacuoles (arrow). Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) Bismuth levels in HK-2 from A, cystine supplementation dramatically elevated bismuth uptake (***P < 0.0001). (C) Fluorescent emission spectra and bismuth level in black particles isolated from BiTracker-treated HK-2 (A3, arrow head). The characteristic emission and 94% of bismuth was only found in black particle. For isolation protocol, see SI Method. (D) Confocal microscopic images of HK-2 treated with BiTracker (50 μΜ for 36 h) and LysoTracker Red DND-99 (50 nM for 30 min before imaging). The cells were treated with (1) LysoTracker, (2) BiTracker and LysoTracker, and (3) 0.5 mM l-BSO for 24 h, BiTracker and LysoTracker. The fluorescence of BiTracker and LysoTracker were colocalized (2), except when GSH were depleted (3). Scale bar: 10 μm. (E) Pictures and fluorescence images of CBS-treated HK-2 (0.5 mM for 72 h) with cystine supplement, without (1) or with (2) 50 μΜ MK571. HK-2 underwent readily observable darkening (1) which can be diminished by MK571 (2). Using AO (0.5 μM for 30 min) to provide background light, numerous black particles were visualized under fluorescence microscope (arrow head). With MK571 treatment, these particles cannot form. Intracellular bismuth levels were also shown in the first row.

Glutathione depletion can also affect bismuth uptake. After incubating with 0.05 mM CBS for 12 h, bismuth level in l-BSO–pretreated HK-2 was ∼0.05 mM, about fivefold lower than normal HK-2 (∼0.3 mM) (Fig. 3D). Moreover, cysteine is a relatively rare amino acid in human cells, a rate-limiting factor of glutathione biosynthesis. After incubating with 0.5 mM CBS for 72 h with cystine supplementation, bismuth level in HK-2 was ∼35 mM, four- to fivefold higher than HK-2 without supplement (∼8.3 mM) (Fig. 3E). These data indicated that glutathione also plays an important role in bismuth uptake.

Bismuth Compartmentalization Is Mediated by Glutathione and MRP Transporter.

Bismuth was repeatedly found metabolized into bismuth sulfide particles inside subcellular vesicles of many different types of mammalian cells (12). To study the subcellular distribution of bismuth, we used a bismuth-loaded fluorescent probe (BiTracker; Fig. S4A). After being incubated with 50 µM BiTracker for 36 h, blue fluorescence of the probe (exited at 365 nm) were exclusively found inside subcellular vesicles at the perinuclear region of HK-2 cells (Fig. 4A, 2 and 3, arrow head). For HK-2 with cystine supplement, the vesicles were significantly enlarged with black particles trapped inside (Fig. 4A3, arrow head). Simultaneously, bismuth level was fourfold elevated (Fig. 4B). We then isolated these black particles by dissolved away the soluble part of cell with 1% SDS and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 min. The collected pellet was then dissolved in 50% HNO3 before examining bismuth content as well as fluorescence using ICP-MS and a fluorescent spectrometer, respectively. As shown in Fig. 4C, ∼94% of total bismuth, all fluorescent signal of BiTracker was detected in the pellet. This concurs with previous autometallography (AMG) experiments, and proved the colocalization of bismuth and the fluorescence (12). BiTracker was also found colocalized with LysoTracker Red DND-99, which indicated that bismuth was located inside the lysosomes (Fig. 4D, 2). Depletion of glutathione with l-BSO caused severe cell vacuolation in BiTracker-treated HK-2 cells (Fig. 4A4, arrow), the blue fluorescence found inside vacuoles did not colocalize with LysoTracker (Fig. 4D3). These data demonstrated the indispensability of glutathione in bismuth compartmentalization.

Interestingly, after 72 h incubation with 0.5 mM CBS, HK-2 cells cultured in cystine-supplemented medium underwent readily observable color changes (Fig. 4E, Top). Using the green fluorescence of acridine orange (AO) as a background, numerous subcellular black particles could be observed under fluorescent microscope (Fig. 4E, arrow head). MK571 is a MRP transporter inhibitor, and we found that addition of MK571 prevented the formation of the black particles and dramatically reduced bismuth uptake from 30 to 2 mM (Fig. 4E, Top). This proves that bismuth compartmentalization is mediated by MRP transporter.

Proteomic Profiling of Bismuth-Treated Human Cells.

Our previous proteomic study on bismuth-treated H. pylori revealed changes of expression levels in a group of bismuth-binding proteins (22). To search for potential bismuth-binding proteins in cells, we used two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DE) to monitor protein-expression level changes in bismuth-treated HK-2 cells. The cells were incubated with 0.5 mM CBS for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h, and proteins with expression level change >twofold were harvested for matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight-mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) protein identification (Fig. S5 A and B). Four proteins were found and identified to be transketolase, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAmPRTase), guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 (RACK1), and annexin A1 (Fig. S5B, Table S2). BiTracker can also be used to track bismuth-binding proteins; UV radiation at 365 nm could link the probe covalently to its binding partner through arylazide (Fig. S4A). However, SDS/PAGE analysis of BiTracker-treated HK-2 showed no fluorescence-labeled protein. Only when cells were glutathione depleted before adding BiTracker, the fluorescence could be found labeling a single protein band subsequently identified to be heat shock protein 27 (Hsp27) (Fig. S5C).

Sequestration-Aided Passive Transport.

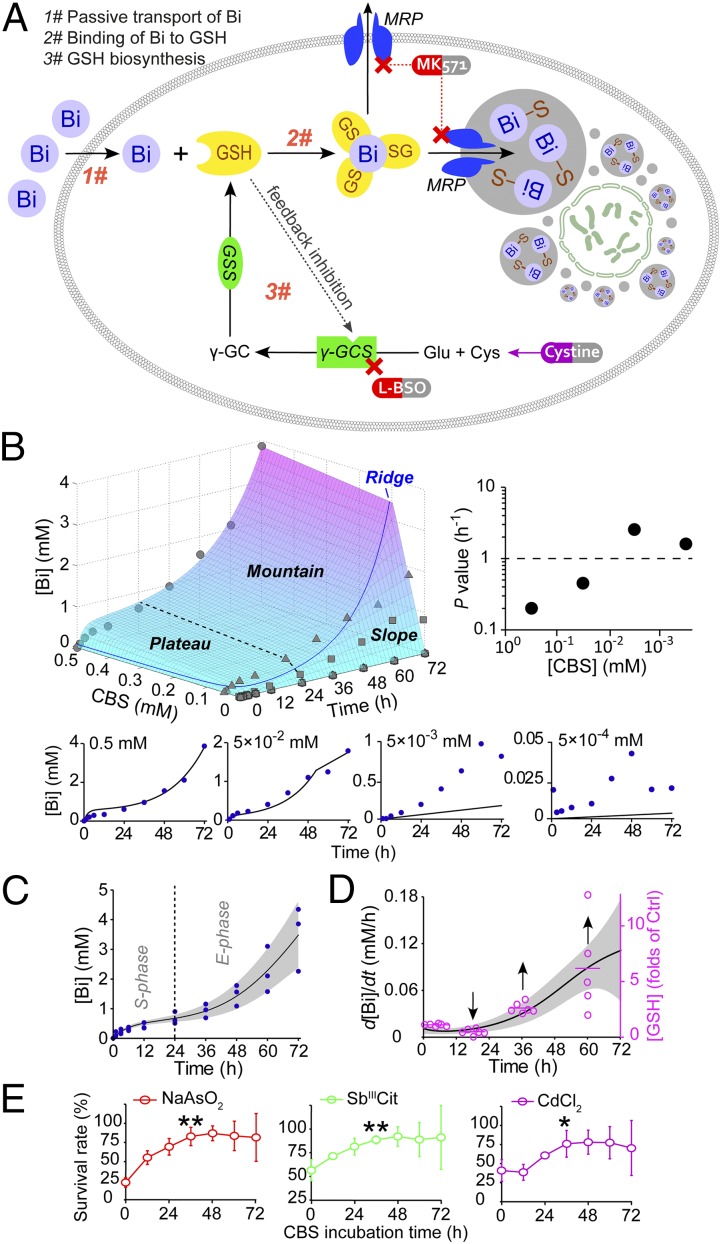

To quantitatively analyze the metabolic pathway of bismuth in human cells, we formulated a mathematical model. Fig. 5A summarized all clues we got so far: bismuth was passively absorbed, conjugated to glutathione, and then transported into vesicles via MRP transporter; sequestration of absorbed bismuth consumed cytosolic glutathione and activated its de novo biosynthesis, which in return facilitated passive uptake of bismuth. They constitute a self-sustaining positive feedback circle, which we named sequestration-aided passive transport.

Fig. 5.

Model of SAPT and data analysis. (A) Schematic diagram depicting SAPT model of bismuth disposal in a human cell. (B) Fitting of time and dosage-dependent bismuth uptake in CBS-treated HK-2 cells to SAPT, revealing a distinguished saturating phase (0–24 h, plateau), an exponential phase (24–72 h, mountain) and a slope, which were separated by a curve on the uptake surface, the ridge. The experimental (blue dots) and simulated (black lines) values of bismuth uptake in HK-2 at different CBS doses are shown (Lower). Upper Right is the values of bismuth permeability P at different CBS doses, indicating higher permeability at lower doses. (C) Bismuth uptake curve of HK-2 treated with 0.5 mM CBS for 0–72 h (black line, gray area is error bars). This curve was generated by fitting three sets of experimental data (blue dots) to SAPT model. (D) The curve of bismuth uptake rate (black line with gray area as error ranges) derived from D as its first derivative, which successfully mimic the fluctuation of glutathione level in 0.5 mM CBS-treated HK-2 (magenta circles). (E) The mitigation of heavy metal toxicity in HK-2 upon treatment of CBS. HK-2 was treated with 0.5 mM CBS for different periods of time before treatment with 15 µM sodium arsenite, 40 µM antimony citrate, or 50 µM cadmium chloride for 24 h. The time of mitigation coincides with the surge of glutathione levels. (**P = 0.0044, **P = 0.0097, and *P = 0.0311, respectively).

This metabolic network in SAPT can be described by five simple rules (as five equations). First, the process of passive transport can be described by Fick’s law (Eq. S1). Second, the binding of bismuth and glutathione is governed by law of mass action (Eq. S6). Third, due to the feedback inhibition of GSH on γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) and constant consumption of GSH by bismuth, the rate of glutathione biosynthesis can be expressed as a logistic function proportional to the total production of Bi(GS)3, which equals the total consumption of GSH in process (Eq. S7). These three functions represent the three major steps of SAPT pathway, which were further restrained by laws of material conservation of glutathione (Eq. S8) and bismuth (Eq. S9).

This group of equations formed a nonlinear complex system, whose solution is algebraically nonexplicit. However, before turning to total numerical analysis, biochemical facts offered us a simple and clear way to put this model. Given the high binding affinity between bismuth and glutathione (formation constant of logK = 29.6) and subsequent MRP compartmentalization, we simply set the dissociation constant (Kd) of Bi3+-glutathione complex [Bi(GS)3] to 0, and an explicit solution emerges (Eq. S10). This solution is the minimum of two functions respectively representing the case when bismuth uptake rate is limited by its membrane permeability (Eq. S10, j1), or by glutathione supply (Eq. S10, j2).

SAPT Analysis of Bismuth Metabolism in CBS-treated HK-2 Cells.

We used Eq. S10 to fit bismuth uptake data of HK-2 cells treated with CBS for varied times and dosages, generating an uptake surface that can be analogically described as a combination of different types of terrain (Fig. 5B). If we travel along the time axis, we will ascend to a slightly tilted “plateau” (first 24 h) and find ourselves at the foot of an abruptly raised “mountain” (24–72 h). At the far right of our horizon, the landscape was suddenly cut by a “slope,” forming a mountain “ridge” that wanders upward to the peak (Fig. 5B, ridge).

The rise of plateau is the result of the concentration difference of bismuth across cell membrane, which triggered the initial uptake. It exhibited the characteristic saturating pattern of passive transport with P value as 0.48 h−1, which concurs with our previous calculation (Fig. 2A). The rise of mountain marked the activation time of glutathione–MRP disposal system (∼36 h), concurs with the time glutathione level surges in CBS-treated HK-2 cells (Fig. 1C).

When we changed the dosage of CBS, an anomaly emerged and revealed some interesting information. At CBS dosage of 0.5 mM and 5 × 10−2 mM, simulated values of bismuth uptake agreed well with experimental data; but at 5 × 10−3 and 5 × 10−4 mM, simulated values are several times lower than the experimental values, which is indicative of a much higher P value at smaller doses (Fig. 5B, Lower). As CBS dosage decreases from 0.5 to 5 × 10−4 mM, the exact P values are 0.20, 0.45, 2.54, and 1.60 h−1, respectively (Fig. 5B, Upper Right). P value is about 10 times higher at the smaller dosage.

As we mentioned, bismuth uptake rate is limited by either its membrane permeability or by glutathione supply (Eq. S10, j1 and j2). When the two forces were evenly matched, j1 equals j2, it generated a set of parametric equations describing a curve in three-dimensional space (Eq. S11), the ridge (Fig. 5B). To the upper left of the ridge, bismuth uptake rate is limited by glutathione supply, to the lower right by membrane permeability of bismuth. At CBS dosage of 0.5 mM, bismuth uptake curve lies far left from the ridge, which indicates that the bismuth uptake rate is mainly controlled by glutathione supply. In other words, in this case, the bismuth uptake rate is a direct indicator of glutathione level. So, when we derived the fluctuation of the bismuth uptake rate through time from the SAPT model, it perfectly matched the glutathione level change in 0.5 mM CBS-treated HK-2 (Fig. 5 C and D).

Because glutathione plays an important role in heavy metal detoxification, we conducted a toxicity test on CBS-treated HK-2 cells with sodium arsenite, antimony citrate, and cadmium chloride. We found that preincubation with 0.5 mM CBS slowly developed a mitigation effect to all three compounds, with the timing perfectly matched to CBS-induced glutathione surge (Fig. 5E; ∼36 h). Even the SD of survival rate was found to grow along with the deviation of glutathione level during 36–72 h.

Discussion

Bismuth compounds have long been used in medicine, particularly for gastrointestinal infections. There were found interacting a variety of biomolecules, mainly thiols, but its main metabolic pathway remains unclear (15, 18, 22). Previous study of bismuth distribution in mammal suggests a unitary disposal system at cellular level (12–14). In this report, we demonstrate that bismuth disposal is mediated by glutathione and multidrug resistant protein in human cells, and is a self-propelled positive feedback process.

Our journey started with the discovery of a persisting biphasic pattern of saturation and exponential growth in bismuth uptake in human cells (Fig. 1A). Quantitative modeling demonstrated that saturation in both human and bacterial cells is resulted from passive transport (Fig. 2 and Supporting Information). In passive transport, a smaller cell means higher permeability (Fig. S1B). It endowed bacteria with much higher permeability than human cells, which might partially explain the drug selectivity of bismuth.

We also found that bismuth consumes glutathione (Fig. 1C). Further analysis revealed an inherent correlation between passive transport and glutathione signal decay in CBS-treated cells (Eqs. S4 and S5) (18). Bismuth not only consumes glutathione, but also activates its biosynthesis. De novo biosynthesis of glutathione is a two-step process: ligation of l-glutamate and l-cysteine by γ-GCS and further ligation with glycine by glutathione synthetase (GSS) (32). Consumption of glutathione by bismuth would break end-product feedback inhibition on γ-GCS and elevate glutathione level (33).

Meanwhile, we demonstrate that >94% of bismuth was conjugated to glutathione and then transported into perinuclear vesicles by MRP (Fig. 4). Inhibition of MRP diminished the formation of these particles and reduced bismuth uptake. It concurs with previously reported MRP transport of metal glutathione conjugates (25, 26, 34, 35). Previous AMG experiments demonstrated that bismuth was exclusively metabolized into bismuth–sulfur particles in subcellular vesicles of different cells and tissues, our data just revealed the molecular mechanism behind the formation of such particles (12–14, 36–38). Moreover, as an important food molecule for glutathione biosynthesis, cystine supplement dramatically enhanced bismuth uptake and enlarged bismuth–sulfur particles. This effect is so prominent that it blackened the cell monolayer. It would be of interest to check if it is also behind clinical cases of bismuth accumulation, such as “bismuth line.”

Directly based on the above biochemical facts, we formulated a mathematical model to describe the disposal system. As shown in Fig. 5, passively absorbed bismuth consumes intracellular glutathione and activates glutathione biosynthesis. Glutathione sequestration facilitates passive uptake of bismuth. They constitute a self-propelled positive feedback circle that we named sequestration-aided passive transport. Fitting of the bismuth uptake data to the SAPT model reveals characteristic patterns of passive transport and positive feedback. It also shows that cells exhibited higher permeability at smaller CBS doses, which is indicative of the existence of CBS transporting channels. Using the SAPT model, we managed to mimic the fluctuation of glutathione level in CBS-treated cells, which then successfully predicted the mitigation CBS induced against heavy metal toxicity.

In proteomic profiling, we found that CBS caused NAmPRTase down-regulation and annexin A1 up-regulation (Table S2). Inhibition of NAmPRTase can exert anti-inflammatory effects and annexin A1 itself is a pivotal inhibitor of inflammation, they might have served as an auxiliary defense mechanism under bismuth stress (39, 40). Hsp27, a chaperone that delivers ubiquitinated proteins to proteasome for degradation (41), was found to interact with bismuth only when glutathione is absent, revealing a sign of cytotoxicity (Fig. S5C).

Glutathione depletion dramatically reduced bismuth uptake and compartmentalization, and the survival rate of cells under bismuth stress (Fig. 3). Meanwhile, these cells underwent severe cell vacuolation, degradation, and nuclear malformation. The pathology is similar to bismuth-treated H. pylori and Giardia lamblia, indicative of a similar toxicology (2, 23). Glutathione was thought to be ubiquitous in all living cells. However, it is absent in many anaerobic or microaerobic bacteria and protozoans, in which cysteine is the major thiol (42–45), as when oxygen is absent, cysteine is a steady source of thiol (45). Human gastrointestinal tract is microaerobic/anaerobic, a perfect habitat for these organisms. Many GIT microbes are lack of glutathione, such as H. pylori and G. lamblia (43, 45). It would be of interest to further investigate how glutathione affects the efficacy of bismuth drugs in microbes.

Clinically, bismuth drugs have also succeeded against other pathogens, such as Treponema pallidum and Entamoeba histolytica, which cause syphilis and dysentery, respectively (46). Once again, none of them produces glutathione. Generally speaking, glutathione is more common in Gram-negative bacteria, which might explain the discrimination of bismuth compounds on Gram-positive bacteria (42, 47). Furthermore, our phylogenetic analysis on γ-GCS and GSS revealed high protein sequence diversity among human and pathogenic bacteria (Fig. S6). And γ-GCS is a heterodimer in human, homodimer in plants and monomer in bacteria. All these differences form a solid base of selectivity. Together with bismuth drugs, selective inhibition of pathogen γ-GCS/GSS in chemical/biological manner might serve as an important antimicrobial therapy in future, with selectivity down to gene level.

Materials and Methods

Human cells were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 with DMEM containing 10% (vol/vol) FBS and 100 U/mL penicillin-streptomycin. The BL21 strain of E. coli was cultured at 37 °C in LB. H. pylori strain 26695 was grown on Columbia agar containing 7% (vol/vol) horse blood in microaerobic environment at 37 °C for 3 d, and transferred to Brucella broth supplemented with 0.2% β-cyclodextrin for further culturing under identical conditions for another day. Metal contents were measured by ICP-MS and proteins were characterized by MALDI-TOF-MS. The passive transport model is derived based on Fick’s law. Details of characterization and the mathematical model are described in Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong SAR (HKU7038/08P, N_HKU752/09), Innovation and Technology Commission (ITS085/14) of Hong Kong SAR, Livzon Pharmaceutical Group and the University of Hong Kong (for the emerging Strategic Research Themes on Integrative Biology) for their support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.H.D. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1421002112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Li H, Sun H. Recent advances in bioinorganic chemistry of bismuth. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2012;16(1-2):74–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sousa MC, Poiares-da-Silva J. Cytotoxicity induced by bismuth subcitrate in giardia lamblia trophozoites. Toxicol In Vitro. 1999;13(4-5):591–598. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(99)00068-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall BJ, Armstrong JA, Francis GJ, Nokes NT, Wee SH. Antibacterial action of bismuth in relation to Campylobacter pyloridis colonization and gastritis. Digestion. 1987;37(Suppl 2):16–30. doi: 10.1159/000199555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keogan DM, Griffith DM. Current and potential applications of bismuth-based drugs. Molecules. 2014;19(9):15258–15297. doi: 10.3390/molecules190915258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun H. 2011. Biological Chemistry of Arsenic, Antimony and Bismuth (Wiley, Chichester, UK), pp xvi.

- 6.Gisbert JP. Helicobacter pylori eradication: A new, single-capsule bismuth-containing quadruple therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(6):307–309. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tay CY, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication in Western Australia using novel quadruple therapy combinations. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(11-12):1076–1083. doi: 10.1111/apt.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naganuma A, Satoh M, Imura N. Prevention of lethal and renal toxicity of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) by induction of metallothionein synthesis without compromising its antitumor activity in mice. Cancer Res. 1987;47(4):983–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jefferiss FJ, Willcox RR, McElligott GL. Treatment of early syphilis with penicillin, neoarsphenamine, and bismuth and with penicillin and bismuth alone. Lancet. 1951;1(6646):83–85. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(51)91167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leussink BT, et al. Bismuth overdosing-induced reversible nephropathy in rats. Arch Toxicol. 2001;74(12):745–754. doi: 10.1007/s002040000190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burns R, Thomas DW, Barron VJ. Reversible encephalopathy possibly associated with bismuth subgallate ingestion. BMJ. 1974;1(5901):220–223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5901.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoltenberg M, Juhl S, Danscher G. Bismuth ions are metabolized into autometallographic traceable bismuth-sulphur quantum dots. Eur J Histochem. 2007;51(1):53–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen A, Stoltenberg M, Søndergaard C, Bruhn M, Danscher G. In vivo distribution of bismuth in the mouse brain: Influence of long-term survival and intracranial placement on the uptake and transport of bismuth in neuronal tissue. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;97(3):188–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2005.pto_973132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoltenberg M, Hutson JC. Bismuth uptake in rat testicular macrophages: A follow-up observation suggesting that bismuth alters interactions between testicular macrophages and Leydig cells. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52(9):1241–1243. doi: 10.1369/jhc.4B6286.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun H, Li H, Harvey I, Sadler PJ. Interactions of bismuth complexes with metallothionein(II) J Biol Chem. 1999;274(41):29094–29101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.29094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang N, et al. Bismuth complexes inhibit the SARS coronavirus. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(34):6464–6468. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin L, Szeto KY, Zhang L, Du W, Sun H. Inhibition of alcohol dehydrogenase by bismuth. J Inorg Biochem. 2004;98(8):1331–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadler PJ, Sun H, Li HY. Bismuth(III) complexes of the tripeptide glutathione (γ-L-Glu-L-Cys-Gly) Chemistry. 1996;2(6):701–708. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boogaard PJ, Slikkerveer A, Nagelkerke JF, Mulder GJ. The role of metallothionein in the reduction of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by Bi3+-pretreatment in the rat in vivo and in vitro. Are antioxidant properties of metallothionein more relevant than platinum binding? Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;41(3):369–375. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90533-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gyurasics A, Koszorús L, Varga F, Gregus Z. Increased biliary excretion of glutathione is generated by the glutathione-dependent hepatobiliary transport of antimony and bismuth. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44(7):1275–1281. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(92)90526-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang LH, et al. Abundant expression of zinc transporters in the amyloid plaques of Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge R, et al. A proteomic approach for the identification of bismuth-binding proteins in Helicobacter pylori. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12(6):831–842. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stratton CW, Warner RR, Coudron PE, Lilly NA. Bismuth-mediated disruption of the glycocalyx-cell wall of Helicobacter pylori: Ultrastructural evidence for a mechanism of action for bismuth salts. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43(5):659–666. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.5.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stoltenberg M, Martiny M, Sørensen K, Rungby J, Krogfelt KA. Histochemical tracing of bismuth in Helicobacter pylori after in vitro exposure to bismuth citrate. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(2):144–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cole SP, Deeley RG. Transport of glutathione and glutathione conjugates by MRP1. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27(8):438–446. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leslie EM. Arsenic-glutathione conjugate transport by the human multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs/ABCCs) J Inorg Biochem. 2012;108:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosen BP. Families of arsenic transporters. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7(5):207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01494-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mielniczki-Pereira AA, et al. The role of the yeast ATP-binding cassette Ycf1p in glutathione and cadmium ion homeostasis during respiratory metabolism. Toxicol Lett. 2008;180(1):21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rajagopal A, Simon SM. Subcellular localization and activity of multidrug resistance proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(8):3389–3399. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-11-0704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodish H, et al. 2000. Diffusion of small molecules across phospholipid bilayers. Molecular Cell Biology, 4th ed. (W. H. Freeman, New York), Sect 15.1.

- 31.Volkmer B, Heinemann M. Condition-dependent cell volume and concentration of Escherichia coli to facilitate data conversion for systems biology modeling. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e23126. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smirnova GV, Oktyabrsky ON. Glutathione in bacteria. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2005;70(11):1199–1211. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0248-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Richman PG, Meister A. Regulation of γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase by nonallosteric feedback inhibition by glutathione. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(4):1422–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ballatori N, Hammond CL, Cunningham JB, Krance SM, Marchan R. Molecular mechanisms of reduced glutathione transport: Role of the MRP/CFTR/ABCC and OATP/SLC21A families of membrane proteins. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204(3):238–255. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wortelboer HM, et al. Glutathione-dependent transport of heavy metal compounds by multidrug resistance proteins MRP1 and MRP2. Drug Metab Rev. 2006;38:116–117. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stoltenberg M, Schiønning JD, Danscher G. Retrograde axonal transport of bismuth: An autometallographic study. Acta Neuropathol. 2001;101(2):123–128. doi: 10.1007/s004010000274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoltenberg M, Larsen A, Zhao M, Danscher G, Brunk UT. Bismuth-induced lysosomal rupture in J774 cells. APMIS. 2002;110(5):396–402. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2002.100505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danscher G, Stoltenberg M, Kemp K, Pamphlett R. Bismuth autometallography: Protocol, specificity, and differentiation. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48(11):1503–1510. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perretti M, Dalli J. Exploiting the Annexin A1 pathway for the development of novel anti-inflammatory therapeutics. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(4):936–946. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pittelli M, et al. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) activity is essential for survival of resting lymphocytes. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92(2):191–199. doi: 10.1038/icb.2013.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parcellier A, et al. HSP27 is a ubiquitin-binding protein involved in I-kBα proteasomal degradation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2003;23(16):5790–5802. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5790-5802.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fahey RC, Brown WC, Adams WB, Worsham MB. Occurrence of glutathione in bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1978;133(3):1126–1129. doi: 10.1128/jb.133.3.1126-1129.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown DM, Upcroft JA, Upcroft P. Cysteine is the major low-molecular weight thiol in Giardia duodenalis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61(1):155–158. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fahey RC, Newton GL, Arrick B, Overdank-Bogart T, Aley SB. Entamoeba histolytica: A eukaryote without glutathione metabolism. Science. 1984;224(4644):70–72. doi: 10.1126/science.6322306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hazell SL, Harris AG, Trend MA. 2001. Evasion of the toxic effects of oxygen. Helicobacter Pylori: Physiology and Genetics, eds Mobley HLT, Mendz GL, & Hazell SL (ASM Press, Washington, DC)

- 46.Degos R. Bismuth in the treatment of syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 1977;16(5):391–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1977.tb00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kotani T, et al. Antibacterial properties of some cyclic organobismuth(III) compounds. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(7):2729–2734. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2729-2734.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.