Abstract

Here we report a unique reaction between phenyl diselenide-ester substrates and H2S to form 1,2-benzothiaselenol-3-one. This reaction proceeded rapidly under mild conditions. Thiols could also react with the diselenide substrates. However, the resulted S–Se intermediate retained high reactivity toward H2S and eventually led to the same cyclized product 1,2-benzothiaselenol-3-one. Based on this reaction two fluorescent probes were developed and showed high selectivity and sensitivity for H2S. The presence of thiols was found not to interfere with the detection process.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), traditionally known as a venomous gas with a stinky smell, has been recently recognized as an important signaling molecule.1−5 H2S is generated in mammalian cells by enzymes including cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3-MST), and cysteine and derivatives serve as the substrates.4−8 Recent studies have revealed a variety of functions of H2S in physiological and pathological processes.9−11 However, the mechanisms behind those roles are still poorly understood. H2S is a highly reactive molecule that can react with many biological targets such as hemoglobin and phosphodiesterase.12 These reactions are responsible for the biological functions of H2S. On the other hand, these complicated reactions also make the detection of H2S in biological systems very difficult. Early reports claim physiological H2S concentrations can be as high as 20–80 μM in plasma. However, it is believed now that the concentrations of free H2S are low, at submicromolar or nanomolar levels.12b

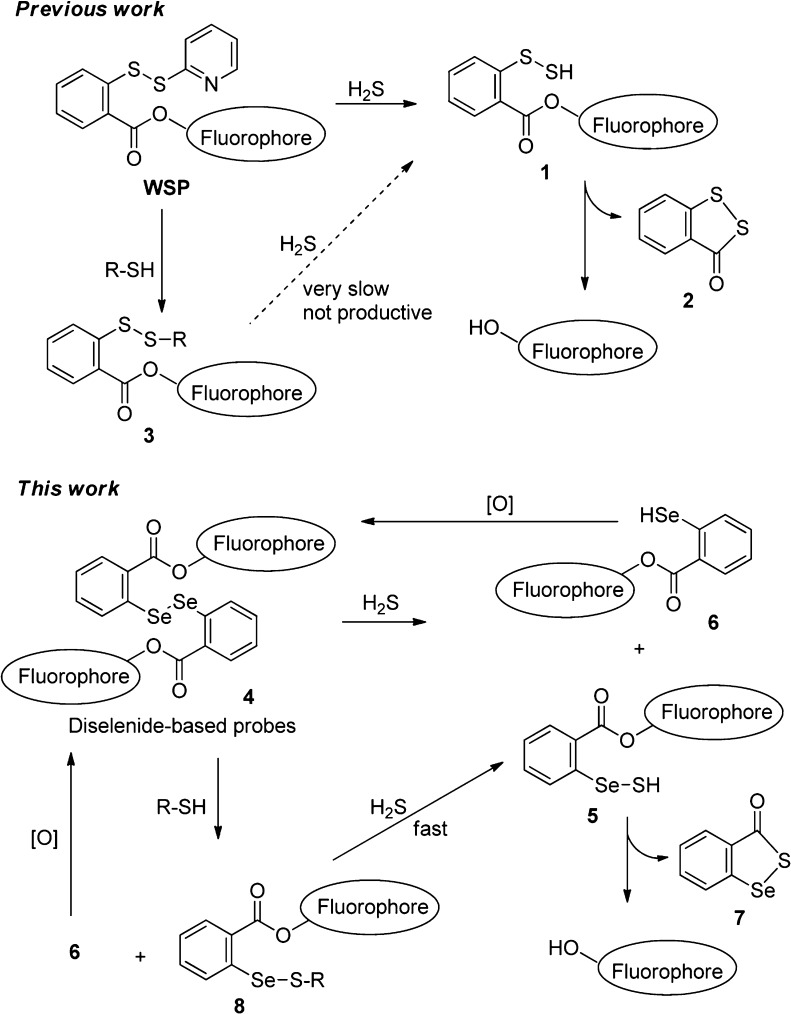

In the past several years fluorescence based assays have received considerable attention in this field and a number of fluorescent probes for H2S have been reported.13 All of these probes utilize reaction-based fluorescence change strategies, i.e. using certain H2S-specific reactions to convert nonfluorescent substrates to materials with strong fluorescence or to change the fluorescent properties of the probes (for ratiometric probes). Currently three types of reactions are normally used in the design of probes: (1) H2S-mediated reductions, often using azide (−N3) substrates;14 (2) H2S-mediated nucleophilic reactions;15,16 and (3) H2S-mediated metal–sulfide formation.17 In 2011 our laboratory developed the first nucleophilic reaction based strategy for the design of probes (i.e., WSP series).15 The strategy is described in Scheme 1. The probe (WSP) contains two electrophilic centers. H2S reacts with the pyridyl disulfide first to give a persulfide intermediate 1, which precedes a fast cyclization to release the fluorophore and 1,2-benzodithiol-3-one 2. It is anticipated that the probe can also react with biothiols to form 3. Theoretically 3 could further react with H2S to form 1 and then turn on the fluorescence. However, this reaction is somewhat slow, especially when the concentration of H2S is low (under physiological conditions18). In addition, H2S may react with both sulfurs of the disulfide of 3, which makes this pathway not productive. It should be noted that the reaction between WSP and biothiols cannot turn the fluorescence on; therefore, the selectivity of WSP is found to be excellent. We were also able to optimize the detection conditions and found fluorescence “turn-on” could be achieved in a few minutes. Such a fast reaction allows effective detection of H2S even when high concentrations of biothiols are presented, albeit the fluorescence signals are significantly decreased.15b

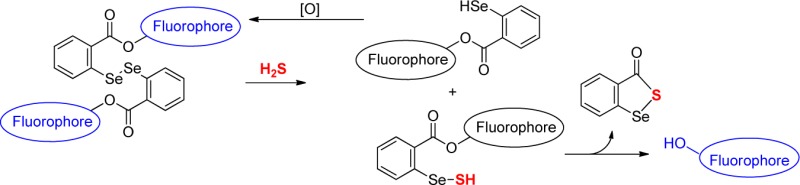

Scheme 1. Design of the Fluorescent Probes for H2S Detection.

As described above, the possible consumption of WSP probes by biothiols is a weakness. To solve this problem two strategies may be applied: (1) a H2S-specific “trapper” should be used to replace the pyridyl-disulfide. Such a trapper should only react with H2S, not react with biothiols. This might be difficult as intracellular concentrations of biothiols are much higher than H2S; (2) a nonconsumptive trapper with biothiols should be identified and used. Such a trapper may react with biothiols, but the reaction should not lead to the release of the fluorophore. Moreover, ideally the reaction product or intermediate should maintain high reactivity toward H2S which therefore can lead to fluorescence “turn-on” by H2S. Herein we report our progress in pursuing the latter strategy. Diselenide-based substrates were found to be suitable for this goal.

Our design of the diselenide-based strategy for the selective trapping of H2S (not consumed by biothiols) is shown in Scheme 1. It is known that diselenide bonds can be cleaved by sulfur-based nucleophiles very effectively (about 5 orders of magnitude faster than disulfide bonds).19,20 It is also known that diselenides can facilitate disulfide formation from thiols.21 H2S (pKa 6.8) is a stronger nucleophile than common biothiols such as Cys and GSH. Therefore, we expect diselenide-based reagents such as 4 should react with H2S very effectively. As such two products should be formed: a thio-benzeneselenol derivative 5 and a benzeneselenol derivative 6. As an extremely unstable intermediate, benzeneselenol 6 should be rapidly oxidized to reform the probe 4.22 In contrast, 5 should undergo a fast and spontaneous cyclization to form 1,2-benzothiaselenol-3-one 7 and release the fluorophore. We also expected the diselenide bond should be quite reactive to biothiols (RSH). Such reactions should lead to two products: 6 and a S–Se conjugate 8. Again, 6 should be oxidized to regenerate the probe. As for 8, previous studies revealed that nucleophilic attack by thiols at selenium is both kinetically much faster and thermodynamically more favorable.19 As such, the reaction between 8 and other biothiols should not change the probe’s structural template (i.e., maintaining the −S–Se– conjugation). However, if H2S is present, the reaction should lead to intermediate 5, and the following cyclization should produce 7 and the fluorophore. Overall we expected the probe would specifically react with H2S to release the fluorophore and the presence of biothiols should not interfere with the process.

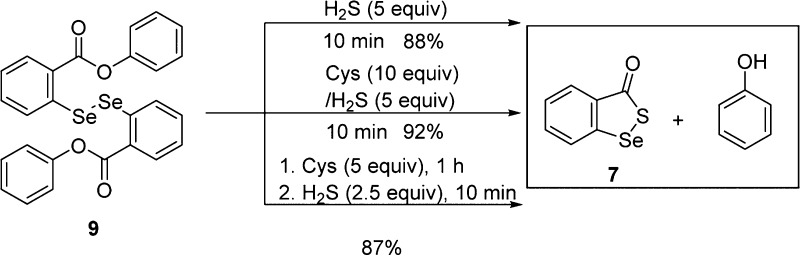

With this idea in mind, a model compound 9 was prepared and tested. As shown in Scheme 2, the reaction between compound 9 and H2S (5 equiv, using Na2S as the equivalent) was found to be fast, which completed in 10 min. The desired products 7 and phenol were obtained in excellent yields. The yield of 7 was calculated based on two selenium moieties in the starting material. We did not observe the formation of the benzeneselenol product in the reaction. When Cys (10 equiv) coexisted with H2S (5 equiv) in the reaction, we obtained the same products in high yields. More interesting, even if Cys (5 equiv) was treated with 9 first for 1 h, the addition of H2S (2.5 equiv) still provided the desired products in similar yields. These results supported our hypothesis that diselenide-based substrates could selectively and effectively react with H2S to form the cyclized product 7 and this reaction was not affected by thiols.

Scheme 2. Model Reactions between Compound 9 and H2S.

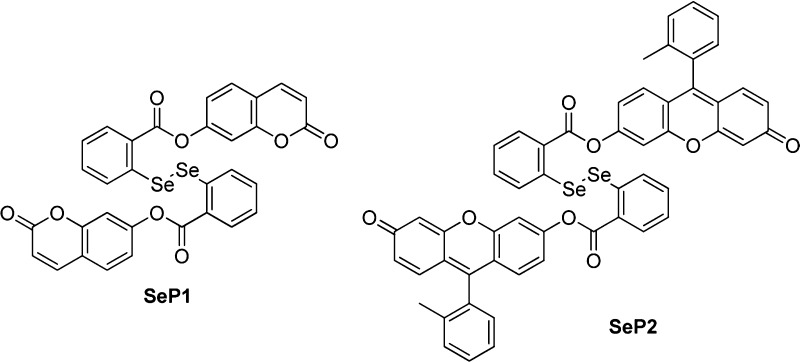

Based on this unique reaction we synthesized two fluorescent probes SeP1 and SeP2 (shown in Figure 1). 7-Hydroxycoumarin and 2-methyl TokyoGreen were selected as the fluorophores, as they have excellent fluorescence properties and their fluorescence can be easily quenched upon acylation on hydroxy groups.

Figure 1.

Structures of diselenide-based probes.

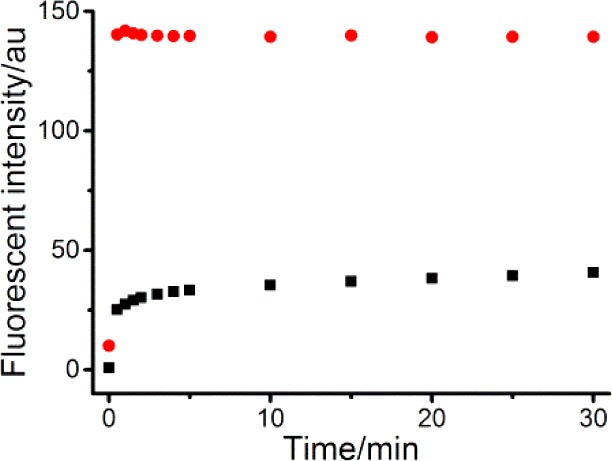

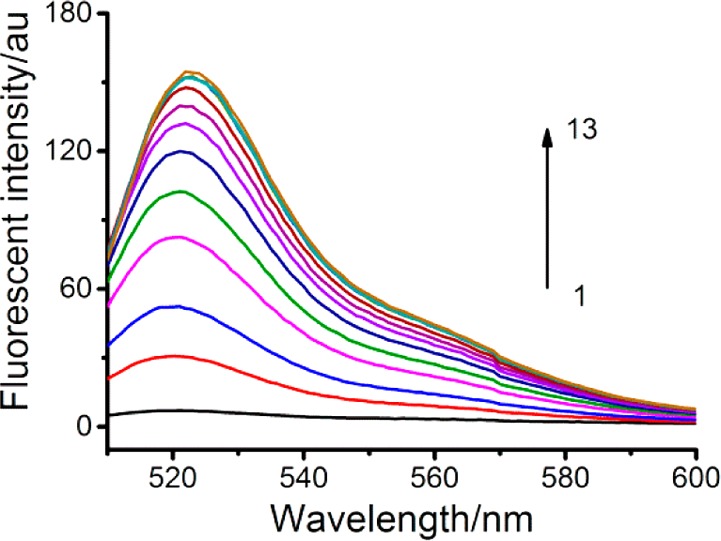

With these two probes in hand, we tested their fluorescent properties. Both probes exhibited very weak fluorescence with low quantum yields (Φ < 0.1), due to esterification of the fluorophores. We then tested the probes’ fluorescence responses to H2S in different solvent systems, and a mixed CH3CN/PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4, 1:1) solution was found to be the optimum system for the measurement. In this system the fluorescence intensity of the probe (10 μM) could reach the maximum in less than 2 min upon treatment of H2S (using 50 μM Na2S) as shown in Figure 2, demonstrating this was a fast process. Fluorescence increases were also found to be significant. Intensities increased 35- and 14-fold for probe SeP1 and SeP2 respectively. When a series of different concentrations of Na2S were treated with the probes we observed fluorescence intensities increased in almost a linear fashion in the range 0–15 μM. Data obtained with SeP2 are shown in Figure 3. The detection limit of SeP2 was calculated to be 0.06 μM. Data of SeP1 are shown in Figure S1 in the Supporting Information.

Figure 2.

Time-dependent fluorescence changes of the probes (10 μM) in the presence of Na2S (50 μM). The reactions were carried out for 30 min at room temperature in CH3CN/PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4, 1:1, v/v). Data were acquired at 455 nm with excitation at 340 nm for SeP1 (■) and at 521 nm with excitation at 498 nm for SeP2 (●).

Figure 3.

Fluorescence emission spectra of SeP2 (10 μM) in the presence of varied concentrations of Na2S (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15 μM). The reactions were carried out for 5 min at room temperature in CH3CN/PBS buffer (10 mM, pH 7.4, 1:1, v/v). Data were acquired with excitation at 498 nm for SeP2.

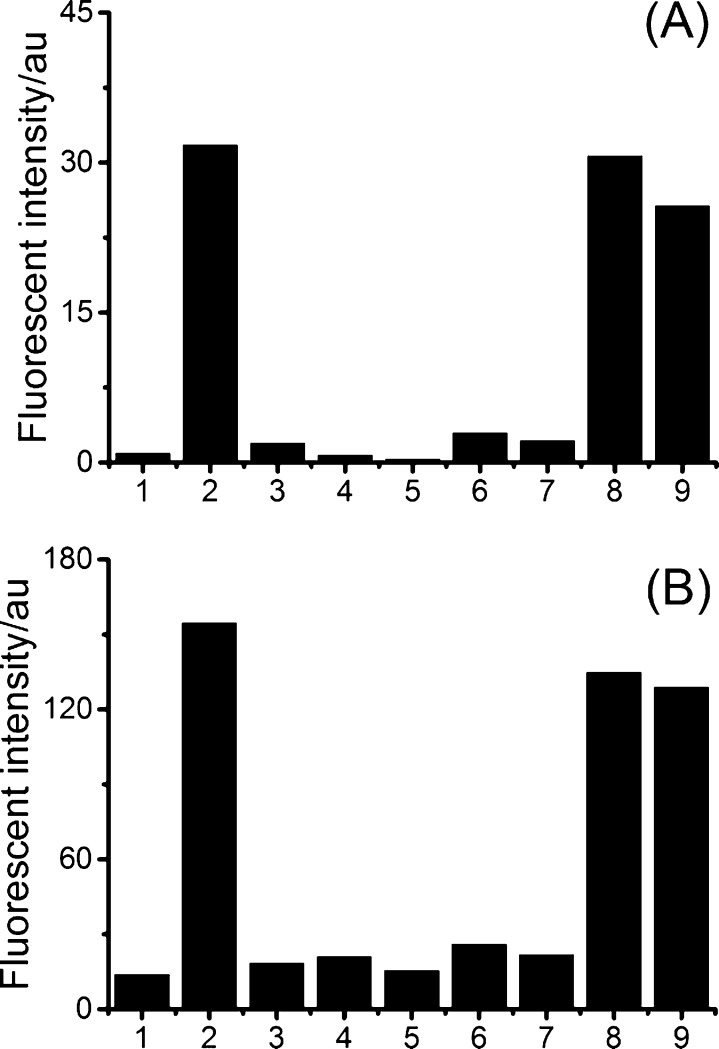

We also examined the selectivity of the probes for H2S over other reactive sulfur species, including cysteine (Cys), glutathione (GSH), sulfite (SO32–), sulfate (SO42–), and thiosulfate (S2O32–). As shown in Figure 4, all of these species did not show a significant fluorescence increase even under much higher concentrations (up to mM). In addition, when H2S (50 μM) coexisted with Cys or GSH (1 mM), we observed strong fluorescence responses that were comparable (at ∼90% levels) to the signals obtained with H2S only. This was a significant improvement from our pyridyl disulfide based probes, which gave much decreased fluorescence when high concentrations of biothiols were present (at 25–55% levels of the signal of H2S only).15b

Figure 4.

Fluorescence intensity of the probes (10 μM) in the presence of various reactive sulfur species: (1) control; (2) 50 μM Na2S; (3) 200 μM Na2SO3; (4) 200 μM Na2S2O3; (5) 200 μM Na2SO4; (6) 1 mM Cys; (7) 1 mM GSH; (8) 50 μM Na2S + 1 mM Cys; (9) 50 μM Na2S + 1 mM GSH. SeP1 (A), SeP2 (B).

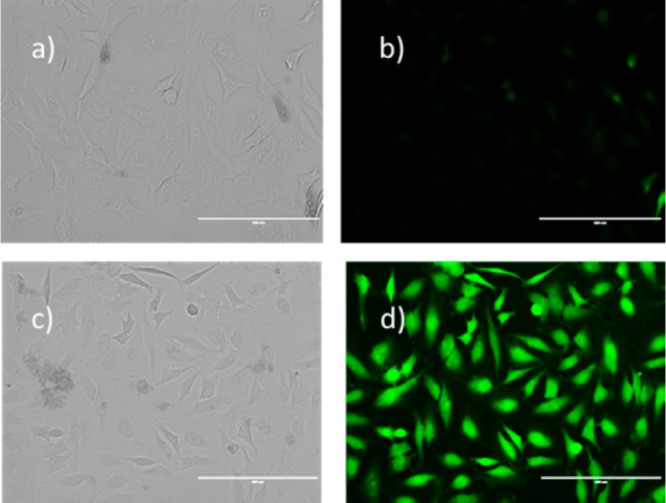

Next we tested SeP2 in imaging H2S in cells. Freshly cultured HeLa cells were first incubated with SeP2 (50 μM) for 30 min and then washed with DMEM to remove excess probe. We did not observe significant fluorescent cells (Figure 5). However, strong fluorescence in the cells was observed after treating with Na2S (100 μM) for 30 min. These results demonstrated that SeP2 could be used for cell imaging.

Figure 5.

Fluorescence images of H2S in HeLa cells using SeP2. Cells were incubated with the probe (50 μM) for 30 min, then washed, and subjected to different treatments. (a and b) Control (no Na2S was added); (c and d) treated with 100 μM Na2S (scale bar: 100 nm).

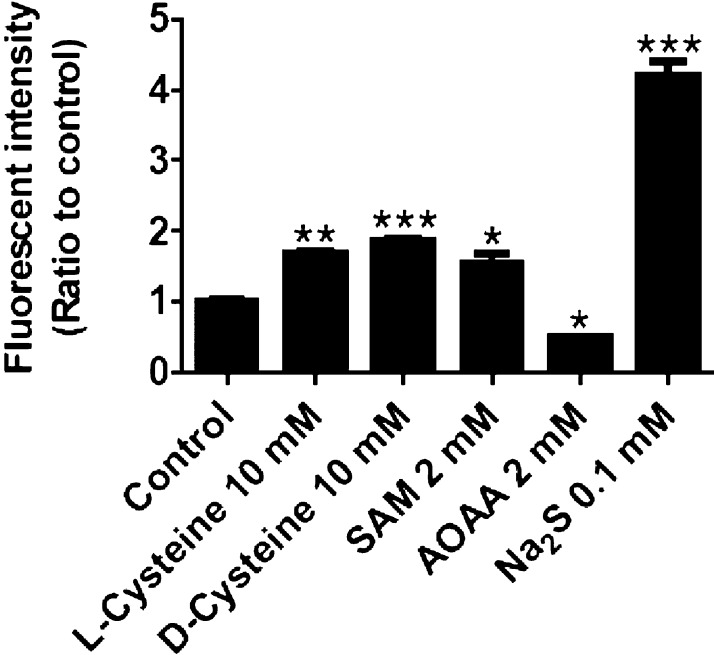

Finally we wondered if SeP2 could be used to measure endogenous H2S concentrations changes. To this end, human neuroblastoma cells (SH-SY5Y) were separately treated with l- and d-cysteine (which are H2S biosynthestic substrates), S-adenosylmethyonine (SAM, a CBS activator), and aminooxyacetic acid (AOAA, a CBS inhibitor). SeP2 was loaded into each experiment before or after treatments (see detailed protocols in the Supporting Information). Fluorescence intensities were measured by a plate reader and compared to both negative and positive controls. As shown in Figure 6, cells treated with H2S substrates or CBS activator showed clearly enhanced fluorescence while cells treated with CBS inhibitor showed decreased fluorescence. Not surprisingly cells treated with Na2S showed the strongest fluorescence. These results suggest that SeP2 can be used in determining endogenous H2S changes.

Figure 6.

Fluorescent detection of in situ generated H2S in human neuroblastoma cells (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs control; N = 5 each).

In conclusion, we reported herein a unique reaction between phenyl diselenide and H2S to form 1,2-benzothiaselenol-3-one. The presence of thiols did not affect this process. Based on this reaction two fluorescent probes for the detection of H2S were prepared and evaluated. The probes showed excellent sensitivity and selectivity.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by an American Chemical Society Teva USA Scholar Grant and the NIH (R01HL101930 and R01HL116571).

Supporting Information Available

Detailed synthetic procedures, characteristic data, and experimental procedures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

∥ B.P. and C.Z. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Li L.; Moore P. K. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2011, 51, 169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuto J. M.; Carrington S. J.; Tantillo D. J.; Harrison J. G.; Ignarro L. J.; Freeman B. A.; Chen A.; Wink D. A. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2012, 25, 769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti T. L. Int. J. Toxicol. 2010, 29, 569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolluru G. K.; Shen X.; Bir S. C.; Kevil C. G. Nitric Oxide 2013, 35, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. Physiol. Rev. 2012, 92, 791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabil O.; Banerjee R. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 21903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabil O.; Banerjee R. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2014, 20, 770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura H. Amino Acids 2011, 41, 113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabil O.; Motl N.; Banerjee R. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1844, 1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ríos-González B. B.; Román-Morales E. M.; Pietri R.; López-Garriga J. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2014, 133, 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock J. T.; Whiteman M. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bibli S.-I.; Yang G.; Zhou Z.; Wang R.; Topouzis S.; Papapetropoulos A. Nitric Oxide 2014, 10.1016/j.niox.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ono K.; Akaike T.; Sawa T.; Kumagai Y.; Wink D. A.; Tantillo D. J.; Hobbs A. J.; Nagy P.; Xian M.; Lin J.; Fukuto J. M. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2014, 77, 82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Peng H.; Chen W.; Cheng Y.; Hakuna L.; Strongin R.; Wang B. Sensors 2012, 12, 15907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pluth M. D.; Bailey T. S.; Hammers M. D.; Montoya L. A.. Biochalcogen Chemistry: The Biological Chemistry of Sulfur, Selenium, and Tellurium, Vol. 1152; Baysel C. A., Brumaghim J. L., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 2013; p 15. [Google Scholar]; c Lin V. S.; Chen W.; Xian M.; Chang C. J. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 10.1039/C4CS00298A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Peng B.; Xian M. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2014, 3, 914. [Google Scholar]; e Li X.; Gao X.; Shi W.; Ma H. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lippert A. R.; New E. J.; Chang C. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peng H.; Cheng Y.; Dai C.; King A. L.; Predmore B. L.; Lefer D. J.; Wang B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wan Q.; Song Y.; Li Z.; Gao X.; Ma H. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhang J.; Guo W. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 4214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Liu C.; Pan J.; Li S.; Zhao Y.; Wu L. Y.; Berkman C. E.; Whorton A. R.; Xian M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 10327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Peng B.; Chen W.; Liu C.; Rosser E. W.; Pacheco A.; Zhao Y.; Aguilar H. C.; Xian M. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20, 1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Qian Y.; Karpus J.; Kabil O.; Zhang S. Y.; Zhu H. L.; Banerjee R.; Zhao J.; He C. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu J.; Sun Y.-Q.; Zhang J.; Yang T.; Cao J.; Zhang L.; Guo W. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 4717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chen Y.; Zhu C.; Yang Z.; Chen J.; He Y.; Jiao Y.; He W.; Qiu L.; Cen J.; Guo Z. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sasakura K.; Hanaoka K.; Shibuya N.; Mikami Y.; Kimura Y.; Komatsu T.; Ueno T.; Terai T.; Kimura H.; Nagano T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hou F.; Cheng J.; Xi P.; Chen F. L.; Huang G.; Xie Y.; Shi H.; Liu D.; Bai Z.; Zeng Dalton Trans. 2012, 41, 5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Furne J.; Saeed A.; Levitt M. D. Am. J. Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008, 295, R1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Whiteman M.; Trionnaire S. L.; Chopra M.; Fox B.; Whatmore J. Clinical Science 2011, 121, 459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann D.; Nauser T.; Koppenol W. H. J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 6696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach S. M.; Demoin D. W.; Luk M.; Miller J. V. J. Phys. Chem. A 2004, 108, 4040. [Google Scholar]

- a Beld J.; Woycechowsky K. J.; Hilvert D. ACS Chem. Biol. 2010, 5, 177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Joris Beld J.; Woycechowsky K. J.; Hilvert D. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 6985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Metanis N.; Hilvert D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 5585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen B.; Sørensen A.; Gotfredsen H.; Pittelkow M. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 3716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.