Abstract

Older military veterans are at greater risk for psychiatric disorders than same-aged non-veterans. However, little is known about factors that may protect older veterans from developing these disorders. We considered whether an association exists between the potentially stress-reducing factor of resistance to negative age stereotypes and lower prevalence of the following outcomes among older veterans: suicidal ideation, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Participants consisted of 2031 veterans, aged 55 or older, who were drawn from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, a nationally representative survey of American veterans. The prevalence of all three outcomes was found to be significantly lower among participants who fully resisted negative age stereotypes, compared to those who fully accepted them: suicidal ideation, 5.0% vs. 30.1%; anxiety, 3.6% vs. 34.9%; and PTSD, 2.0% vs. 18.5%, respectively. The associations followed a graded linear pattern and persisted after adjustment for relevant covariates, including age, combat experience, personality, and physical health. These findings suggest that developing resistance to negative age stereotypes could provide older individuals with a path to greater mental health.

Keywords: Aging, Age stereotypes, Mental health, Stress, Suicide, Anxiety, Posttraumatic stress disorder, Veterans

Considerable media attention has been directed at suicides of current military personnel and young veterans of the United States armed forces (e.g., National Public Radio, 2013). In contrast, journalists have overlooked evidence that the approximately nine-and-a-half million veterans aged 65 and older have a greater risk of suicide than younger veterans, as well as higher rates of other psychiatric conditions, such as anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), compared to same-aged non-veterans (Fanning & Pietrzak, 2013; Ikin et al., 2007; Selim et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2006; United States Census Bureau, 2013).

Little is known about factors that may protect older veterans from developing these psychiatric conditions. Accordingly, we conducted the first study of whether resistance to negative age stereotypes (defined as deprecating beliefs about older people as a category) is associated with a lower likelihood of suicidal ideation (a risk factor for suicide deaths and attempts (Kuo et al., 2001; Simon et al., 2013), anxiety, and PTSD. The current study was based on data from a nationally representative sample of older American veterans.

There are several reasons for assuming that resistance to negative age stereotypes, which are often present in media, marketing, and everyday conversations (e.g., Levy, 2009), may protect against developing psychiatric conditions. For example, the stress-vulnerability model posits that those with less exposure to environmental stressors are less likely to experience a variety of psychiatric conditions, compared to those who are more exposed (e.g., Rozanov and Carli, 2012). Experimental studies have demonstrated that negative age stereotypes assimilated by older individuals from their culture can act as environmental stressors by exacerbating cardiovascular responses to stress, whereas positive age stereotypes can mitigate the harmful effect of these stressors (Levy, Hausdorff, Hencke, & Wei, 2000). This association of negative age stereotypes with stress and stress-related outcomes may explain why negative views of aging have been linked to a significantly greater number of depressive symptoms in older individuals (Sarkisian et al., 2005; Wurm and Benyamini, 2014).

In the current study, we hypothesized that greater resistance to negative age stereotypes would be associated with a reduced likelihood of screening positive for suicidal ideation, anxiety, and PTSD.

1. Methods

1.1. Sample

Participants, aged 55 and older, were drawn from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study (NHRVS), a nationally representative survey of American veterans that was conducted from October to December, 2011. The NHRVS sample was recruited from a research panel of more than 80,000 households that was developed and is maintained by Knowledge Networks. For inclusion, participants needed to answer “Yes” to an initial screening question: “Have you ever served on active duty in the U.S. Armed Forces, Military Reserves, or National Guard?” The response rate of those participants who were 55 or older and who confirmed their current or past active military status was 94%. To permit generalizability of study results to the larger population of older veterans, post-stratification weights were applied to the NHRVS sample based on the demographic distribution (i.e., age, gender, race, education, Census region, and metropolitan area) drawn from the population survey that most closely corresponded to the time frame when the NHRVS data were gathered (i.e., United States Census Bureau, 2010).

Inclusion criteria for the current study were: responses to all questions related to the main predictor variable (i.e., resistance to negative age stereotypes); at least one of the dependent variables (i.e., suicidal ideation, anxiety, and PTSD); and all covariates. The final sample consisted of 2031 veterans, ranging in age from 55 to 93 years, with an average age of 68.8 years (SD = 7.7). The majority was male (95.1%), white (82.3%), educated beyond high school (68.1%), married or living with a significant other (76.6%), had an annual income of at least $35,000 (72.7%), did not have combat experience (62.5%), and reported three or more physical-health conditions (60.1%).

1.2. Measures

1.2.1. Independent variable: Resistance to Negative Age Stereotypes

Resistance to negative age stereotypes was assessed using three items selected by NHRVS from the 12-item Expectations Regarding Aging (ERA) Survey (Sarkisian et al., 2005). Negative expectations regarding aging can be considered a subset of negative age stereotypes, because both are based on beliefs about a wide variety of decrements in old age; but negative expectations regarding aging include a prediction about future decline (Levy, Slade, Kunkel & Kasl, 2002; Meisner and Baker, 2013; Sarkisian et al., 2005). The three ERA items were: “Every year that people age, their energy levels go down a little more; ” “Forgetfulness is a natural occurrence just from growing old; ” and “It is normal to be depressed when you are old.” These items showed the highest factor loadings for the ERA domains of physical health, cognitive function, and mental health, respectively, in the original validation study of the instrument (Sarkisian et al., 2005). Participants were asked whether they felt each item was Definitely true, Somewhat true, Somewhat false, or Definitely false in the current study, participants who responded Definitely true were assigned a score of 0 to indicate full acceptance of that belief, and participants who responded Somewhat true, Somewhat false, or Definitely false were assigned a score of 1 to indicate any degree of resistance. These responses were summed and divided into four categories: full acceptance = 0 (none of the negative age stereotypes were resisted); slight resistance = 1 (one of the negative age stereotypes was resisted); moderate resistance = 2 (two of the negative age stereotypes were resisted); and full resistance = 3 (three of the negative age stereotypes were resisted).

In secondary analyses, negative age stereotypes were examined as a continuous variable in which responses to the individual items (scored from 0 = Definitely true to 3 = Definitely false) were summed to yield a total score that ranged from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating greater resistance. The average score was 4.24 (SD = 1.60), below the midpoint, which suggests that, on average, participants endorsed negative age stereotypes.

1.3. Dependent variables

1.3.1. Current Suicidal Ideation

Current suicidal ideation was assessed with two questions from the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., 2009), which measured the frequency of active and passive suicidal ideation in the past two weeks (Thompson et al., 2004): “Thoughts of hurting yourself in some way” (active ideation), and “Thoughts that you might be better off dead” (passive ideation). Responses were 0 = Not at all, 1 = Several days, 2 = More than half the days, and 3 = Nearly every day. The average score of the sample was 0.14 (SD = 0.60). Participants with a score of 1 or greater were characterized as having current suicidal ideation. These questions have been used to identify individuals at increased risk of suicide deaths and attempts (Simon et al., 2013).

1.3.2. Current Anxiety

Current anxiety was assessed using two questions, covering the preceding two weeks, from the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (Kroenke et al., 2009), a self-report screening instrument: “How often have you been bothered by (1) Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge?; (2) Not being able to stop or control worrying?” Responses were 0 = Not at all, 1 = Several days, 2 = More than half the days, and 3 = Nearly every day. The average score of the sample was 0.42 (SD = 1.01). Participants with combined scores of 3 or greater, the recommended cut-off point, were characterized as having current anxiety (Kroenke et al., 2009). This scale has good predictive validity for generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder (Kroenke et al., 2007).

1.3.3. Current PTSD

To assess lifetime-trauma exposures, participants responded to the Trauma History Screen, which assesses 14 types of potentially traumatic events (e.g., war and sexual assault; Carlson et al., 2011). In the NHRVS, an additional event was added: “life-threatening physical illness or injury.” If participants reported experiencing multiple events, they were asked to select the “worst stressful event.” PTSD symptoms in response to this event were assessed using the 17-item PTSD Checklist, Specific Stressor Version (PCL-S), which is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-lV) PTSD diagnostic criteria (Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Participants indicated how much they had “been bothered by each symptom in the past month” by selecting: 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little bit, 3 = Moderately, 4 = Quite a bit, or 5 = Extremely. Positive-symptom endorsement was indicated by a score of 3 or greater (Weathers et al., 1993). Probable PTSD was operationalized as a total PCL-S score of 50 or greater (Weathers et al., 1993). For this sample, the mean total PCL-S score was 23.87 (SD = 9.48).

DSM-IV PTSD-symptom clusters were a secondary outcome. The PCL-S includes questions that correspond to each of the DSM-IV PTSD-symptom clusters: re-experiencing (5 items; range 5–25), avoidance (7 items; range 7–35), and hyperarousal (5 items; range 5–25). These outcomes were analyzed as continuous variables.

1.4. Covariates

Covariates that have been found by others to be associated with the three psychiatric outcomes (Fanning & Pietrzak, 2013; Ikin et al., 2007; Kaplan et al., 2006) were incorporated into multivariate models. These included: demographic variables of age, sex, race/ethnicity, annual household income, years of education, and marital status; health variable of number of physical-health conditions; trauma-related variable of lifetime trauma exposures, as measured by number of traumatic events and combat experience; psychosocial variable of resilience, as measured by the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (Campbell-Sills and Stein, 2007); and personality variables of extraversion and emotional stability, as measured by the Ten Item Personality Inventory (Gosling et al., 2003). In bivariate analyses, these variables were significantly associated at the p < .05 level with all of the psychiatric outcomes in our cohort, except for: education, which was not significantly associated with any of the outcomes; sex, which was only associated with PTSD; and emotional stability, which was only associated with anxiety. We included all of these covariates in multivariate models in order to examine whether the predictor impacted the outcomes above and beyond established contributing factors.

1.5. Data analysis

To examine the hypothesis that participants who reported greater resistance to negative age stereotypes would be less likely to experience suicidal ideation, anxiety, and PTSD, we first conducted bivariate analyses using the two-sided Cochran-Armitage test for linear trend (Agresti, 2002). The prevalence of each psychiatric condition at each level of the categorical predictor variable was presented as a weighted percentage. We then conducted multivariate-logistic-regression models with resistance to negative age stereotypes entered as an independent variable, and each of the three outcomes as a dependent variable, in separate models. These models adjusted for all of the covariates (i.e., age, sex, years of education, race/ethnicity, marital status, annual household income, lifetime trauma exposure, combat experience, number of physical health conditions, resiliency, extraversion, and emotional stability).

In secondary analyses, we conducted Pearson correlations to examine whether greater resistance to negative age stereotypes was associated with lower scores for each of the three PTSD-symptom clusters. We then conducted multivariate-linear-regression models with the same predictor and the three clusters as the outcomes, adjusting for all of the covariates.

To confirm that significant results were not due to the categorical nature of the independent variable, we repeated all models with the continuous version of this variable, adjusting for all covariates.

2. Results

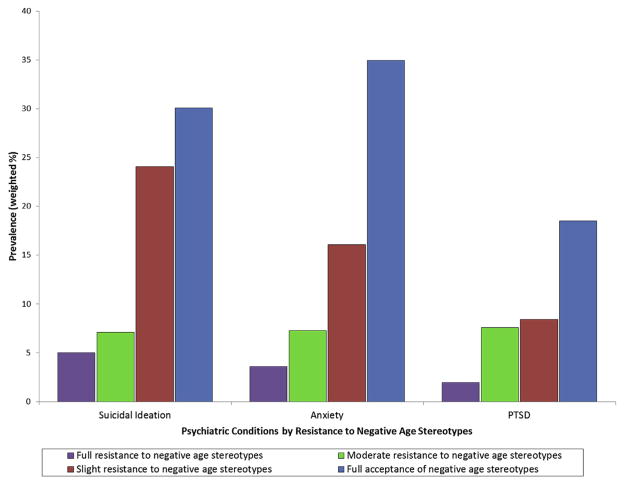

Bivariate analyses revealed that older veterans’ resistance to negative age stereotypes was linearly and significantly associated with screening positive for suicidal ideation (Cochran–Armitage test for trend; Z = 7.26, p < .001), anxiety (Z = 7.58, p < .001), and PTSD (Z = 6.22, p < .001). As can be seen in Fig. 1 and Table 1, the three psychiatric conditions showed the hypothesized pattern of decreasing prevalence as resistance to negative age stereotypes increased. That is, veterans with full resistance to negative age stereotypes had the lowest prevalence of all three outcomes, followed by those with moderate resistance, then those with slight resistance, and, finally, those who fully accepted the negative age stereotypes.

Fig. 1.

Association of Resistance to Negative Age Stereotypes with Lower Prevalence of Suicidal Ideation, Anxiety, and PTSD among Older Veterans.

Table 1.

Resistance to Negative Age Stereotypes Associated with Lower Odds of Psychiatric Conditions, after Adjustment for Covariates.

| Psychiatric Outcomes

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suicidal Ideation

|

Anxiety

|

PTSD

|

|||||||

| %a | ORb | 95% CI | %a | ORb | 95% CI | %a | ORb | 95% CI | |

| Resistance to Negative Age Stereotypes | |||||||||

| Full Resistance | 5.0 | 0.30 | 0.10, 0.88 | 3.6 | 0.08 | 0.02, 0.25 | 2.0 | 0.14 | 0.03, 0.64 |

| Moderate Resistance | 7.1 | 0.38 | 0.12, 1.19 | 7.3 | 0.14 | 0.04, 0.47 | 7.6 | 0.71 | 0.16, 3.16 |

| Slight Resistance | 24.1 | 1.55 | 0.47, 5.13 | 16.1 | 0.47 | 0.13, 1.70 | 8.4 | 0.97 | 0.18, 5.17 |

| Full Acceptance | 30.1 | 1.00 | – | 34.9 | 1.00 | – | 18.5 | 1.00 | – |

| P < .0001 | p < .0001 | p < .0001 | |||||||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Weighted prevalence of each psychiatric condition; row %.

All models were adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, annual household income, education, marital status, number of physical-health conditions, number of traumas, combat experience, resilience, extraversion, and emotional stability.

In regression models adjusted for all covariates, the same pattern was observed, with the risk of each outcome decreasing as a function of increasing resistance to negative age stereotypes. For example, compared to participants who reported full acceptance of negative age stereotypes, those who reported full resistance were 70% (p < .05) less likely to meet screening criteria for suicidal ideation, 92% (p < .001) less likely to meet screening criteria for anxiety, and 86% (p < .05) less likely to meet screening criteria for PTSD.

Additionally, in models that included continuous operationalization of the resistance-to-negative-age-stereotype predictor variable, a greater degree of resistance to negative age stereotypes was significantly associated with lower prevalence of the three outcomes, after adjusting for all covariates. That is, for each one-point increase in resistance to negative age stereotypes, the probability of suicidal ideation, anxiety, and PTSD decreased by 20% (p < .001), 17% (p < .05), and 18% (p < .05), respectively.

In evaluating possible interaction effects, it was found that combat experience did not moderate the association of resistance to negative age stereotypes with PTSD (X2 = 1.50, df = 3, p = .68).

In Pearson-correlation analyses, scores for the three DSM-IV PTSD-symptom clusters of re-experiencing (r = −0.10, p < .001), avoidance (r = −0.17, p < .001), and hyperarousal (r = −0.17, p < .001) decreased in severity as resistance to negative age stereotypes increased. This pattern was also observed in fully adjusted multivariate linear regression models: participants who fully resisted negative age stereotypes reported lower severity of re-experiencing symptoms (β = 0.26, B = −1.75, p < .01), avoidance symptoms (β = −0.34, B = −3.44, p < .0001), and hyperarousal symptoms (β = −0.34, B = −2.44, p < .0001), compared to those who fully accepted these stereotypes.

3. Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, the association between greater resistance to negative age stereotypes and lower prevalence of suicidal ideation, anxiety, and PTSD followed a graded linear pattern in which the rate of these conditions significantly decreased as a function of this resistance. To illustrate, the prevalence of each psychiatric condition was significantly lower among participants who fully resisted negative age stereotypes, compared to those who fully accepted these stereotypes: suicidal ideation, 5.0% vs. 30.1% (p < .0001); anxiety, 3.6% vs. 34.9% (p < .0001); and PTSD, 2.0% vs. 18.5% (p < .0001).

The robustness of the association between negative age stereotypes and the three psychiatric outcomes was demonstrated in several ways. First, the findings persisted after adjustment for the covariates of potential relevance to the study population, among them were physical health, age, personality factors, and marital status. Second, the expected pattern was found in a diversity of psychiatric outcomes, including PTSD and its three symptom clusters. Third, because older veterans, in contrast to same-aged non-veterans, are at increased risk for the three psychiatric conditions (Selim et al., 2004), a greater impact of negative-age-stereotype resistance would be necessary to achieve the outcomes than would be the case among less susceptible individuals.

Although we assumed that resisting negative age stereotypes would help to protect individuals from developing psychiatric conditions, the cross-sectional design of the current study did not allow us to ascertain the directionality of this association. However, in support of our assumption, previous experimental studies have shown that age stereotypes influence cognitive and physical outcomes (e.g., Levy & Leifheit-Limson, 2009); and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that age stereotypes at baseline predict cognitive and physical outcomes assessed many years later (e.g., Levy et al., 2002; Levy, Slade, Murphy, & Gill, 2012; Levy, Zonderman, Slade and Ferrucci, 2009, 2011; Wurm et al., 2007).

The generalizability of the current study’s results to older individuals who are not veterans can be inferred in two ways. First, the underlying premises, that positive age stereotypes tend to have beneficial consequences and negative age stereotypes tend to have detrimental consequences, were developed from research with older non-veterans (e.g., Levy, 2009). Second, a moderator analysis revealed that resistance to negative age stereotypes was not differentially associated with PTSD among veterans who experienced combat relative to those who had not.

The findings of this study underscore the potential importance of taking negative age stereotypes into account when considering the etiology of later-life psychiatric conditions. More encouraging, the results suggest that developing resistance to those stereotypes could provide older individuals with a path to greater mental health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants to Becca Levy from the National Institute on Aging (R01AG023993), and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL089314). Corey Pilver was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health postdoctoral fellowship (5-T32-MH01423537). The National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study and Robert Pietrzak were supported by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20:1019–1028. doi: 10.1002/jts.20271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson EB, Smith SR, Palmieri PA, Dalenberg C, Ruzek JI, Kimerling R, Burling TA, Spain DA. Development and validation of a brief self-report measure of trauma exposure: the trauma history screen. Psychol Assess. 2011;23:463–477. doi: 10.1037/a0022294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Rentfrow PJ, Swann WB. A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains. J Res Pers. 2003;37:504–528. [Google Scholar]

- Fanning JR, Pietrzak RH. Suicidality among older male veterans in the United States: results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. J Psychiat Res. 2013;47:1766–1775. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikin JF, Sim MR, McKenzie DP, Horsley KW, Wilson EJ, Moore MR, Jelfs P, Harrex W, Henderson S. Anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression in Korean War veterans 50 years after the war. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:475–483. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan MS, Huguet N, McFarland BH, Newsom JT. Suicide among male veterans: a prospective population–based study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;61:619–624. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.054346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Lowe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Lowe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317–325. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo WH, Gallo JJ, Tien AY. Incidence of suicide ideation and attempts in adults: the 13-year follow-up of a community sample in Baltimore, Maryland. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1181–1191. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy B. Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Hausdorff JM, Hencke R, Wei JY. Reducing cardiovascular stress with positive self-stereotypes of aging. J Gerontol Psychol Sci. 2000;55:205–213. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.4.p205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Leifheit–Limson E. The stereotype-matching effect: greater in-fluence on functioning when age stereotypes correspond to outcomes. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:230–233. doi: 10.1037/a0014563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Kunkel SR, Kasl SV. Longevity increased by positive self-perceptions of aging. J Personal Soc Psychol. 2002;83:261–270. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Slade MD, Murphy TE, Gill TM. Association between positive age stereotypes and recovery from disability in older persons. JAMA. 2012;308:1972–1973. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Zonderman AB, Slade MD, Ferrucci L. Age stereotypes held earlier in life predict cardiovascular events in later life. Psychol Sci. 2009;20:296–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy BR, Zonderman AB, Slade MD, Ferrucci L. Memory shaped by age stereotypes over time. J Gerontol Ser B: Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;67:432–436. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meisner BA, Baker J. An exploratory analysis of aging expectations and health care behavior among aging adults. Psychol Aging. 2013;28:99–104. doi: 10.1037/a0029295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Public Radio. All things considered 2013 Jan 14; [Google Scholar]

- Rozanov V, Carli V. Suicide among war veterans. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9:2504–2519. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9072504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Steers WN, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Development of the 12-item expectations regarding aging survey. Gerontologist. 2005;45:240–248. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selim AJ, Berlowitz DR, Fincke G, Cong Z, Rogers W, Haffer SC, Ren XS, Lee A, Qian SX, Miller DR, Spiro A, 3rd, Selim BJ, Kazis LE. The health status of elderly veteran enrollees in the Veterans Health Administration. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2004;52:1271–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, Ludman E. Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempts or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Henkel V, Coyne JC. Suicidal ideation in primary care: ask a vague question, get a confusing answer. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:455–456. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000127691.46148.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Factors for Features: Veterans Day. Washington, DC: 2013. Nov 11, [accessed 19.09.13]. http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/facts_for_features_special_editions/cb13-ff27.html. [Google Scholar]

- United States Census Bureau. Current Population Survey. US Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Weathers F, Litz B, Herman D, Huska J, Keane T. The PTSD checklist (PCL): reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper Presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. Oct, 1993. [accessed 19.09.13]. from: http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/pages/assessments/ptsd-checklist.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Wurm S, Benyamini Y. Optimism buffers the detrimental effect of negative self-perceptions of ageing on physical and mental health. Psychol Health. 2014;7:832–848. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.891737. Epub 2014 Mar 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurm S, Tesch-Romer C, Tomasik MJ. Longitudinal findings on aging-related cognitions, control beliefs, and health in later life. J Gerontol: Psychol Sci. 2007;62:156–164. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.3.p156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]