Abstract

Background/Purpose

The study aimed to develop a mouse model of post-pullthrough Hirschsprung’s disease that will allow investigation of mechanisms that cause postoperative complications.

Methods

We developed a novel microsurgical pullthrough operation on Balb/C mice and evaluated its effect on growth rate and stooling pattern. Histologic assessment of the pullthrough colon was performed. The pullthrough operation was then performed on Ednrb−/− mice that have aganglionic megacolon and Ednrb+/+ littermate controls, and the outcomes compared.

Results

The Balb/C pullthrough group had 97% survival at 1 week and 70% survival at 2 weeks. Body weight of the pullthrough animals declined 15% in the first week after surgery and subsequently normalized. The stooling pattern showed consistently softer stools in the pullthrough group, but no difference in frequency compared to controls. Histopathologic analyses 4 weeks postoperatively showed well-healed coloanal anastomoses. Two-week survival after pullthrough surgery in Ednrb−/− and Ednrb+/+ mice was 50.0%, and 69.2%, respectively (P = NS). Increased mortality in the Ednrb−/− mice was related to the technical challenge of performing microsurgery on smaller-sized mice with poor baseline health status.

Conclusions

Our microsurgical pullthrough operation in mice is feasible and allows systematic investigations into potential mechanisms mediating post-pullthrough complications and poor long-term results in mouse models of Hirschsprung’s disease.

Keywords: Hirschsprung’s disease, Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis, Aganglionic megacolon, Microsurgery, Pullthrough, Ednrb-B-null mice

Hirschsprung’s disease (HD, also called congenital aganglionic megacolon) [1,2] occurs when intestinal ganglia in the colon fail to form during development [3–5]. The clinical result is defective peristalisis that can cause intestinal obstruction, recalcitrant constipation, megacolon, severe enterocolitis, and death because of septicemia [6–12]. The precise cause of HD is not well understood; however, a number of associated genetic abnormalities have been implicated [13–16]. Currently, most patients are treated with a 1-stage pullthrough surgery performed soon after birth. In most children, surgical results are satisfactory, but some experience significant and persistent postoperative complications, such as enterocolitis (Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis [HAEC]), intractable constipation, obstructive symptoms, and incontinence [9,17–22]. These complications may adversely affect quality of life many years after the initial surgery [11,12,23]. The pathogenesis of these postoperative complications is difficult to study in children and is poorly understood, partly because suitable animal models are not available.

A number of animal models of HD itself are available [24–28]. Most of these affected animals succumb by 6 to 8 weeks of age owing to intestinal obstruction from aganglionic megacolon. However, these models do not accurately reflect today’s children with HD, who receive pullthrough operations to remove the aganglionic colon and restore fecal continence within the first few months of life, but may nonetheless experience persistent adverse clinical sequelae. Trans-anal pullthrough surgery has been performed in the rabbit [29], but no mouse model of post-pullthrough HD is available. Lack of an optimal animal model that can be widely exploited by investigators slows progress in our understanding of the etiologies of postoperative complications (most notably HAEC) and inhibits development of rational approaches to therapy and prevention. We therefore sought to create a surgical murine model to mimic post-pullthrough HD.

We report here the successful development of micro-surgical techniques to perform a pullthrough operation in wild-type mice. Furthermore, we have performed this procedure on a mouse model of HD, the Ednrb-null (Ednrb−/−) genotype [25], and have characterized the outcomes. The Ednrb−/− phenotype exhibits aganglionic megacolon similar to that seen in HD; however, these mice have limited survival, owing to the severe constipation and enterocolitis that develop after birth. As application of our surgical pullthrough treatment prolongs survival in Ednrb−/− mice, it is now feasible to design mechanistic investigations into the molecular, genetic, and cellular causes of HAEC and other post-pullthrough complications in controlled experimental animal models.

1. Materials and methods

1.1. Animals

Animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Mice (BALB/c and Ednrbtm1Ywa/J on a hybrid C57BL/6J-129Sv background; JAX stock # 003295 [25]) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and housed at the animal facility of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The mice were maintained on a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle at 25°C and received regular mouse chow and water ad libitum. A breeding colony of the Ednrbtm1Ywa/J heterozygous mice was established and maintained at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. The Ednrbtm1Ywa/J is a targeted null mutation of the endothelin receptor B gene that segregates in an autosomal recessive manner. The homozygotes (we designate these as Ednrb−/− in this paper) are easily identified by the white coat color and progressively enlarging abdomens owing to aganglionosis leading to megacolon [25]. The wild-type and heterozyote littermates (we designate these as Ednrb+/+ and Ednrb+/−, respectively) are phenotypically normal and therefore indistinguishable from one another and therefore required genotyping using a polymerase chain reaction–based assay. Three different groups of mice were used in this study. Group 1: 6- to 8-week-old male and female Balb/C mice (n = 87; weight, 18–25 g); group 2: 6- to 7-week-old male and female Ednrb+/+ mice (n = 13; weight, 18–22 g); group 3: 4- to 5-week-old male and female Ednrb−/− mice (n = 20; weight, 11–17 g).

1.2. Preoperative management

Animals were allowed unlimited access to food (regular chow) and water, but were fed a liquid diet (LD101 (PMI Micro-stabilized Rodent Liquid Diet) TestDiet, Richmond, Indiana), Harlan-Teklad, Madison, Wisconsion for 5 days before surgery. Enrofloxacin (80 mg/kg) was given by gavage the day before surgery.

1.3. Microsurgical procedures

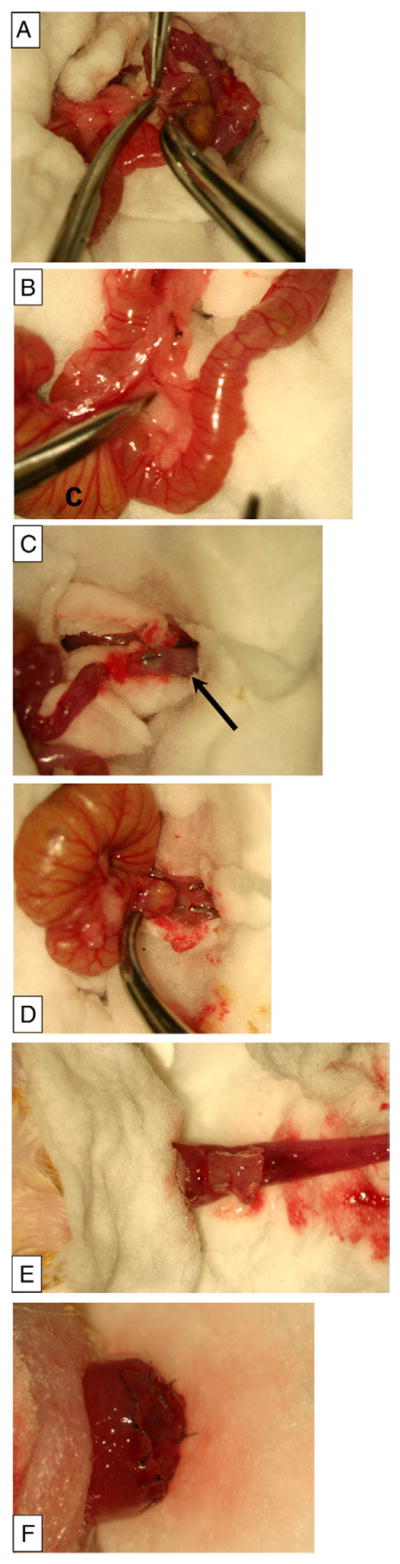

The operation is adapted from that described by Swenson and Bill [30] in 1948 and performed in a single stage. All operations were performed under an operating stereomicroscope with microsurgical technique. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1.5%–2%) inhalational anesthesia. After a 5-to 10-minute induction period, mice were gently restrained in the supine position on a Gaymar warming unit, and buprenorphine hydrochloride (0.05 mg/kg) was administered by deep intramuscular injection. Abdominal fur was clipped, and the abdominal wall and perineal skin were cleansed thoroughly with povidone iodine solution. A midline laparotomy was performed and the small bowel eviscerated. The mobile portion of the distal colon was identified and a mesenteric window was created. The mesentery was divided, and the short arcade vessels were coagulated with a bipolar cautery moving toward the cecum (Fig. 1A). The proximal mesentery continued to be delicately divided adjacent to the colon wall until the colon became mobilized enough to reach to the anus without tension (Fig. 1B). The colon was transected with great care to preserve the marginal artery which served as the blood supply for the pullthrough segment. Upward traction was applied to the mobilized distal colon, which facilitated sharp division of the peritoneal reflection and blunt mobilization of the rectum. The distal colon was inverted on itself by insertion of curved forceps into the anus that were advanced to where the transected end could be grasped (Fig. 1C). Next, the forceps were withdrawn, inverting the distal colon through the anus, until the anorectal junction could be seen.

Fig. 1.

Pullthrough operation in Balb/C mice. A, Mobilization of the proximal colon by creation of a mesenteric window and division of the short arcade vessels after bipolar cautery. B, Mobilized proximal colon to reach the anus, and preservation of the arcade to feed marginal vessels. The label C indicates the cecum. C, Forceps tip pointing through the transected distal colon segment (black arrow), before inversion of this segment. D, Forceps grasping the proximal colon to pull it through the inverted distal rectum. E, The pullthrough segment (proximal colon) pulled through the hemi-transected distal rectum. F, The completed anastomosis before inversion into the anus.

1.3.1. Pullthrough procedure

The anterior half of the inverted rectum was transected 1 to 2 mm proximal to the anorectal junction. A pair of small curved forceps was placed through the transection site and advanced into the peritoneal cavity to where the transected end of the mobilized proximal colon was grasped, then carefully pulled through the hemi-transected distal rectum (Fig. 1D). There was no tension on the pullthrough segment, and the end of the pullthrough segment was assessed for adequate perfusion and trimmed before anastomosis (Fig. 1E).

1.3.2. Anastomosis

The anterior half of the anastomosis was completed with interrupted sutures using 9–0 nylon, then the posterior half of the inverted distal colon was completely transected and the posterior half of the anastomosis was completed (Fig. 1F). The anastomosis was gently inverted back into the anus. Finally, the muscle and skin were closed individually with running 4–0 polylglycolic acid suture, and 300 μL of warmed saline was injected subcutaneously.

1.3.3. Postoperative care

After recovery from anesthesia, mice were placed into a fresh cage in an incubator at 33°C, which was adjusted 2 hours later to 30°C overnight. The following day the mouse was returned to a standard cage and room. To control postoperative pain, the mouse was given buprenorphine every 12 hours subcutaneously for the first 36 hours. Enrofloxacin (80 mg/kg) was given by gavage every 24 hours for 5 days. The animal was given 300 μL of saline subcutaneously daily for the first 3 postoperative days. Feeding was resumed using 5% dextrose water–soaked chow and liquid diet immediately after surgery; in addition, mice were supplied with 5% of dextrose water in the first 24 hours. Most mice passed stool within the first 24 hours. One week after the operation, the diet was changed to standard mouse chow.

1.4. Post pullthrough evaluation and histopathologic assessment

Complications were evaluated by necropsy of all animals that died in the early postoperative period (defined as <2 weeks after pullthrough operation). Body weight was also recorded and monitored for 8 weeks. Stooling pattern (number of stools per day and consistency of stool) was assessed at 3 weeks after pullthrough operation, by housing animals individually with wire bottom cages for a period of 7 days and counting the number of stools on a daily basis. Stool consistency was graded as: “formed-solid,” “formed-soft,” “loose,” and “liquid.” Weights and stool patterns were compared with age-matched nonsurgical controls. For mice that succumbed more than 2 weeks after pullthrough operation, the anus and pullthrough segments were dissected en bloc, and tissues were processed (fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin embedded, and sectioned at 8 μm). The anus-pullthrough en bloc segments were embedded and sectioned sagitally, whereas the proximal colon and ileum segments were sectioned transversely. All tissues were stained using hematoxylin and eosin, and evaluated by light microscopy for histologic evidence of healing, anastomotic leak, anastomotic stricture, ischemic changes, and inflammation by one of the authors (DD). Tissues obtained from age-matched nonoperative Balb/C mice served as controls and were handled in an identical manner.

1.5. Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, California). Data were expressed as means ± SD or SEM. P values less than .05 were regarded as statistically significant.

2. Results

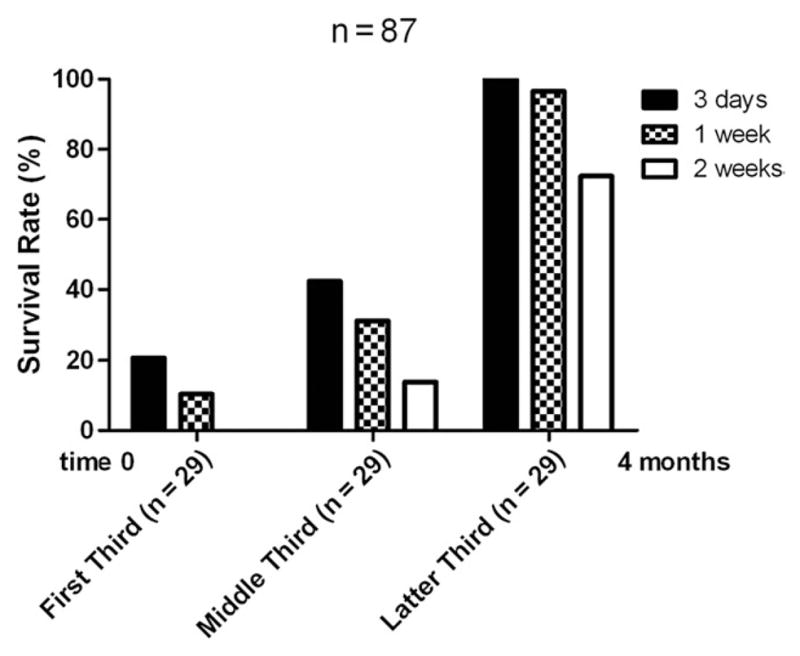

2.1. Survival rate of Balb/C mice during development of the pullthrough operation

To develop a 1-stage pullthrough operation to treat HD in the mouse, we used 6- to 8-week-old Balb/C mice (n = 87). We performed pullthrough microsurgery on 3 successive groups consisting of 29 mice in each group. Fig. 2 shows the survival rate of post-pullthrough Balb/C mice over a 4-month period, when our microsurgical technique and perioperative care strategies were developing. Continual refinement of our operative technique led to steady improvement in survival. In the first group, 1- and 2-week survival was 10% and 0%, respectively. In the middle group, these survival times were 31% and 14%, and in the final group, these survival times had improved to 97% and 70%, respectively. To evaluate long-term survival after pullthrough operation, mice were followed for 4 months, at which time they appeared healthy and had weights comparable to control mice (data not shown). One mouse was kept alive for 6 months.

Fig. 2.

Survival of Balb/C mice after pullthrough operation. Eighty-seven Balb/C mice underwent the microsurgical pullthrough operation over a 4-month span. The group of mice was subdivided into 3 equal groups of 29 mice consisting of the first, middle, and last third of our experience during development of the pullthrough operation. Survival at 3, 7, and 14 days after pullthrough operation is compared.

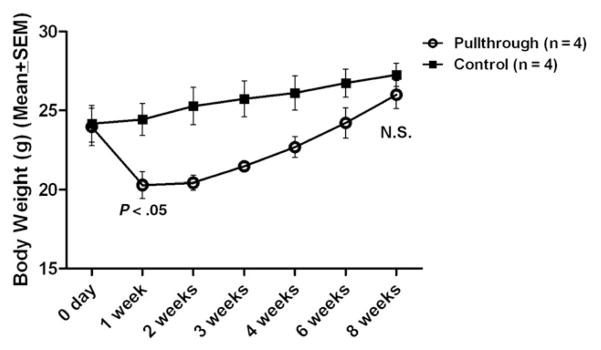

2.2. Effect of pullthrough operation on body weight of Balb/C mice

Fig. 3 shows body weights of Balb/C mice after pullthrough surgery compared to age- and weight-matched control mice that did not undergo surgery. After the pullthrough procedure, the weight dropped markedly and was 15% lower than weight in control mice at 1 week (P < .05). The body weight of the pullthrough group plateaued and thereafter steadily increased at a faster rate than that of the control group. At 8 weeks after surgery, there was no longer a statistically significant difference between body weight in the pullthrough mice versus control mice. Although the surgery led to a marked reduction in body weight during the early postoperative period as expected, the pullthrough operation did not affect the growth of the mice.

Fig. 3.

Body weight of Balb/C mice after pullthrough operation. Eight age- and weight-matched Balb/C mice were used for body weight comparison. Four mice underwent pullthrough surgery, and 4 control mice received no surgery. There was no statistically significant difference in body weight at the start of the experiment, although mice that underwent the pullthrough operation showed a significant decrease in body weight in the first week after surgery (P < .05 Student t test, unpaired, 2 tailed, 95% confidence interval). Eight weeks after pullthrough, there was no statistically significant difference in body weight between the groups.

2.3. Evaluation of stooling patterns in Balb/C mice after pullthrough operation

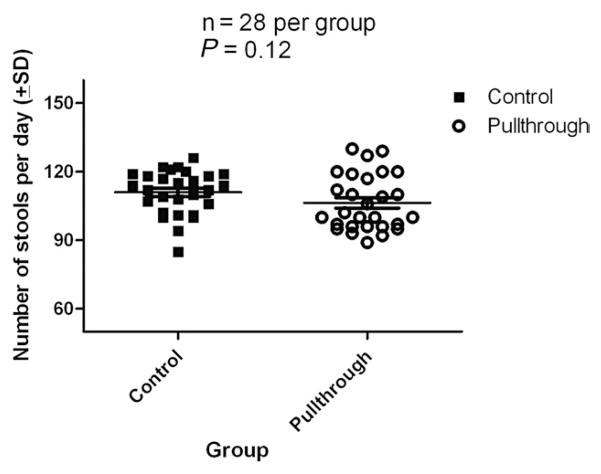

After pullthrough operation, all mice manifested changes in the stool character. Most animals had loose stools in the first week, but stool consistency gradually increased over the next 2 weeks once mice were returned to regular mouse chow. Three weeks after the pullthrough operation, stools were counted daily over a 7-day period and the consistency graded. Mean daily stool number in mice undergoing pullthrough surgery (n = 28) was 106 ± 2. Control nonoperated mice (n = 28) produced a mean of 111 ± 2 stools per day during this same period (Fig. 4). This difference did not reach statistical significance (P = .12). The stool consistency was “formed soft” for 3 of the animals and “loose” for one of the animals in the pullthrough group, whereas all 4 animals in the control group were “formed solid”.

Fig. 4.

Stool frequency after pullthrough operation in Balb/C mice. Mouse stooling frequency (stools per day) was monitored daily over a 7-day period and plotted. Four mice that were 3 weeks status post pullthrough operation were compared with 4 age-matched control mice that did not undergo surgery. There was no statistically significant difference (P = .12 Student t test, unpaired, 2 tailed, 95% confidence interval) in stool frequency.

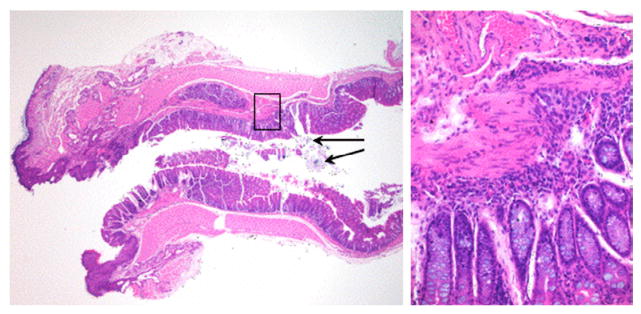

2.4. Histologic assessment of anastomoses in Balb/C mice after pullthrough operation

To evaluate surgical results in more detail, we euthanized a group of mice (n = 5) 4 weeks after pullthrough and resected the colon from the anus to the ileum. We performed sectioning and hematoxylin-and-eosin staining as described in the Materials and Methods section. Fig. 5 shows a representative example of a sagittal section through the anus and anastomosis of the pullthrough segment. A well-healed anastomotic site is apparent that exhibited minimal inflammation. We observed no evidence of anastomotic leaks, anastomotic strictures, ischemic changes, or inflammation in these mice, indicating the operative results were satisfactory. Proximal colon and ileum sections were also taken at multiple levels, and these also demonstrated no histologic changes compared to nonoperated controls (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Histologic evaluation of anastomosis in a Balb/C mouse after pullthrough operation. Left panel: A representative example of a sagittal section through the anus (left), anastomosis, and distal pullthrough colon segment (right) is shown (hematoxylin-and-eosin staining, magnification ×20). The black arrows denote residual suture material from the anastomosis, confirmed with a polarizing filter (data not shown). The black box denotes the area shown in the right panel showing the area of the healed anastomosis region at higher magnification (magnification ×100).

2.5. Post-pullthrough complications in Balb/C mice

To determine the cause of early mortality (<14 days) after pullthrough operation, we conducted necropsy after the death of mice in 3 consecutive groups (n = 29, n = 25, and n = 8). Table 1 summarizes the findings on gross inspection that we believed were the primary cause of death in each animal and the postoperative period when these occurred. Complications included shock or inadequate fluid resuscitation, postoperative bleeding, pullthrough segment necrosis, anastomotic leak, anastomotic stricture or obstruction, and “not determined” if we could not identify the cause. In the first group of mice (n = 29), mortality was attributed to shock and postoperative bleeding (<24 hours), pullthrough segment necrosis, or anastomotic leak (0–3 days postoperatively). Also, operative times were prolonged (>60 minutes), there was frequently excessive blood loss (>300 μL), inadequate fluid resuscitation, and suboptimal postoperative care. In subsequent groups of mice, these complications diminished and did not occur in the last group. In the second and third groups of mice (n = 25 and n = 8, respectively), major contributors to mortality were anastomotic leak and anastomotic stricture/obstruction. The third group had markedly less mortality owing to improved microsurgical technique, decreased operative times (<40 minutes), minimal blood loss (<100 μL), better anesthetic control, and optimized preoperative and postoperative care.

Table 1.

Postoperative complications in Balb/C mice: type and frequency for each group

| Complications | Time of occurrence | First third (n = 29) | Middle third (n = 25) | Last third (n = 8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shock/inadequate fluid resuscitation | <1 d | 12 | 9 | 0 |

| Postoperative bleeding | <1 d | 6 | 4 | 0 |

| Pullthrough segment necrosis | 1–3 d | 5 | 4 | 0 |

| Anastomotic leak | 3–7 d | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Anastomotic stricture/obstruction | >1 wk | 2 | 4 | 5* |

| Not determined | 1 | 1 | 2 |

The complications described were deemed the primary cause of death on gross inspection at the time of necropsy for each animal. The “not determined” classification was used when the cause of death was unclear.

Includes one internal hernia leading to bowel obstruction.

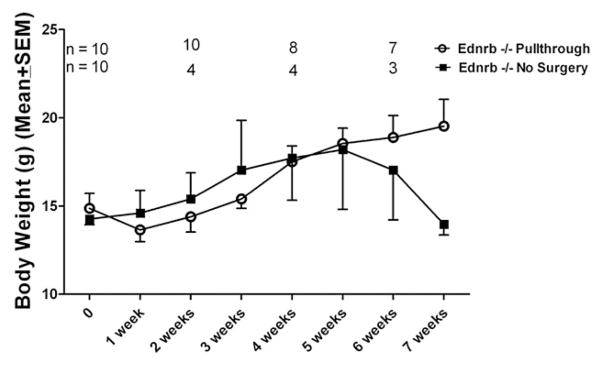

2.6. Pullthrough operation in wild-type Ednrb+/+ mice and Ednrb−/− mice with aganglionic megacolon

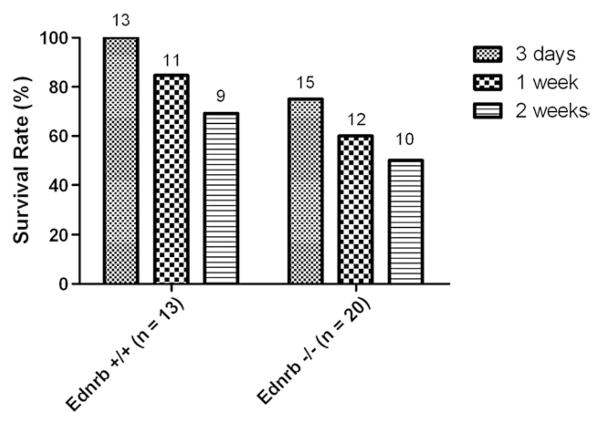

Overall, the pullthrough operation was technically successful and produced satisfactory results in 6- to 8-week-old Balb/C mice. However, the main purpose in developing the operation was to begin to study the mechanisms of postoperative complications and longer-term adverse outcomes after technically satisfactory surgical results, as this occurs clinically in patients with HD [9,17–22]. We therefore sought to perform the operation in the Ednrb−/− mouse, an established mouse model that mimics HD. The Ednrb−/− mice are markedly smaller than the Ednrb+/+ littermates, and the Ednrb−/− mice typically die within 4 to 6 weeks after birth; hence, the Ednrb−/− mice presented a technical challenge. We performed pullthrough operations on Ednrb−/− mice (n = 20; mean weight, 14.4 g) and Ednrb+/+ control mice (n = 13; mean weight, 22.8 g). Two-week postoperative survival was 50.0% and 69.2% in Ednrb−/− mice and Ednrb+/+, respectively (P = NS) (Fig. 6). Shock, postoperative bleeding, and pullthrough segment necrosis were the causes of death within the first 3 postoperative days in Ednrb−/− mice, but not in Ednrb+/+ mice. Later complications included anastomotic leak and anastomotic stricture/obstruction in both groups (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

Survival of Ednrb−/− mice and Ednrb+/+ controls after pullthrough operation. Ednrb+/+ mice (n = 13) and Ednrb−/− mice (n = 20) underwent pullthrough operations. Survival at 3, 7, and 14 days after pullthrough operation is compared. No statistically significant difference was found between the 2 genotypes at each time point.

Table 2.

Postoperative complications: type and frequency in Ednrb+/+ and Ednrb−/− mice

| Complications | Time of occurrence | Ednrb (+/+)(n = 4) | Ednrb (−/−) (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shock/inadequate fluid resuscitation | <1 d | 0 | 3 |

| Postoperative bleeding | <1 d | 0 | 1 |

| Pullthrough segment necrosis | 1–3 d | 0 | 1 |

| Anastomotic leak | 3–7 d | 1 | 1 |

| Anastomotic stricture/obstruction | >1 wk | 2 | 2 |

| Not determined | 1 | 2 |

The complications described were deemed the primary cause of death on gross inspection at the time of necropsy for each animal. The “not determined” classification was used when the cause of death was unclear.

We compared body weights of Ednrb−/− mice after pullthrough surgery with age- and weight-matched control mice that did not undergo surgery (Fig. 7). After the pullthrough procedure, the weight of Ednrb−/− mice dropped markedly compared to that of control mice in the first 3 weeks. By week 5, the mean body weights of both groups were essentially equal. Thereafter, weights of the pullthrough group steadily increased, whereas the mean body weight of the control group decreased. The differences in weight between the 2 groups did not reach statistical significance at any time point. Mortality of 30% and 70% occurred in the pullthrough and the nonsurgery groups, respectively. The higher mortality observed in the non-surgery group during this period is consistent with the known lethality of this strain in both published data and our own experience.

Fig. 7.

Body weight of Ednrb−/− mice after pullthrough operation. Twenty age- and weight-matched Ednrb−/− mice were used for body weight comparison. Ten mice underwent pullthrough surgery, and 10 control mice received no surgery. The differences in body weight between groups did not reach statistical significance at any of the time points. Mean age of the mice at time 0 was 30.7 days for the pullthrough group and 32 days for the no-surgery group. Both groups were followed for 7 weeks, during which time each group sustained mortality reflected in the decreasing n number at 2, 4, and 6 weeks. The observed higher mortality in the nonsurgery group during this period is consistent with that of both published data and our own experience.

3. Discussion

Here we report the development of a novel 1-stage pullthrough surgical procedure in young Balb/C mice. Furthermore, we also successfully performed the procedure in Endrb−/− mice with aganglionic megacolon, a phenotype that mimics HD [25]. After pullthrough operation, more than 80% of Balb/C and Ednrb+/+ mice survived for more than 1 week and about 70% survived for more than 2 weeks, indicating strain background does not play a role in survival. Postoperative survival was less in Ednrb−/− mice; 1- and 2-week survival in these mutant mice with aganglionic megacolon was 60% and 50%, respectively. Mice that survived for 2 weeks continued to recover thereafter. Major factors leading to reduced survival included poorer overall health status (owing to megacolon) and significantly smaller size, which increased the technical challenge of the operation.

Several complications occurred in mice undergoing pullthrough surgery. Early in our experience with the Balb/C, and then subsequently with the Ednrb−/− mice, shock from prolonged operative times, significant blood loss, inadequate fluid resuscitation, and postoperative bleeding were the primary causes of death. As we gained experience, these complications decreased, and instead we encountered delayed anastomotic complications (leak, stricture, or obstruction). However, with greater surgical experience and improved perioperative care, satisfactory survival (50% at 2 weeks) was achieved in Ednrb−/− mice.

The pullthrough operation appears to have no long-term detrimental effect on the growth and health of wild-type mice (both Balb/C and Ednrb+/+) up to 6 months after surgery. Instead, the pullthrough operation had a positive effect on the growth of the Ednrb−/− mice that survived the surgery compared to Ednrb−/− mice that did not receive surgery. Our data therefore suggest that the pullthrough operation confers a survival advantage to the Ednrb−/− mice. However, the numbers of mice presented are small, and a definitive statement regarding survival requires further study.

Our results now allow systematic investigations into mechanisms mediating late complications, persistent unsatisfactory results, and long-term adverse outcomes of HD and HAEC using controlled animal models. Currently, there are at least 8 murine models of hypoganglionic or aganglionic megacolon that manifest a Hirschsprung’s-like syndrome. These include the Hoxb5 dominant negative conditional (Cre-Lox) transgenic genotype [31], erbB2/nestin-Cre conditional mutant mouse [32], the endothelin B receptor (Ednrb)–null mouse [25], the endothelin-3 ligand-deficient mouse [26], the Dom spontaneous mutant mouse [27], a conditional β1 integrin knockout mouse [33], trisomy 16 mice [34,35], and mice deficient in the c-ret protooncogene [36]. In addition, the endothelin B receptor–deficient rat (spotting lethal rat) [37–39] and the fmc/fmc (familial megacecum and colon) rat [40] also display a phenotype that mimics HD. However, all these animals invariably die within a few weeks of birth, precluding study of the pathophysiologic basis of longer-term outcomes. Use of pullthrough surgery in these mouse models can now be performed and will provide important insights into the mechanisms underlying the clinical pathology of both HD and post-pullthrough complications such as HAEC. Such studies could well result in development of rational new therapies for HD and HAEC that are based upon improved understanding of cause-and-effect mechanism.

Footnotes

This work was supported by The Lippey Family Endowment and The Walter and Shirley Wang Endowed Chair in Pediatric Surgery at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

References

- 1.Kessmann J. Hirschsprung’s disease: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1319–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy F, Puri P. New insights into the pathogenesis of Hirschsprung’s associated enterocolitis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:773–9. doi: 10.1007/s00383-005-1551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Di Nardo G, Blandizzi C, Volta U, et al. Review article: molecular, pathological and therapeutic features of human enteric neuropathies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:25–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newgreen D, Young HM. Enteric nervous system: development and developmental disturbances—part 2. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2002;5:329–49. doi: 10.1007/s10024-002-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newgreen D, Young HM. Enteric nervous system: development and developmental disturbances—part 1. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2002;5:224–47. doi: 10.1007/s10024-001-0142-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moore SW. The contribution of associated congenital anomalies in understanding Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:305–15. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belknap WM. The pathogenesis of Hirschsprung disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2002;18:74–81. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200201000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suita S, Taguchi T, Ieiri S, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease in Japan: analysis of 3852 patients based on a nationwide survey in 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.052. discussion 201–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Estevao-Costa J, Fragoso AC, Campos M, et al. An approach to minimize postoperative enterocolitis in Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1704–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nasr A, Langer JC. Evolution of the technique in the transanal pull-through for Hirschsprung’s disease: effect on outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:36–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.028. discussion 39–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Engum SA, Grosfeld JL. Long-term results of treatment of Hirschsprung’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2004;13:273–85. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2004.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vieten D, Spicer R. Enterocolitis complicating Hirschsprung’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2004;13:263–72. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks AS, Oostra BA, Hofstra RM. Studying the genetics of Hirschsprung’s disease: unraveling an oligogenic disorder. Clin Genet. 2005;67:6–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heanue TA, Pachnis V. Enteric nervous system development and Hirschsprung’s disease: advances in genetic and stem cell studies. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:466–79. doi: 10.1038/nrn2137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tam PK, Garcia-Barcelo M. Molecular genetics of Hirschsprung’s disease. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2004;13:236–48. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson K, Mason I, Hall S. Hirschsprung’s disease: genetic mutations in mice and men. Gut. 1997;41:436–41. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleinhaus S, Boley SJ, Sheran M, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease—a survey of the members of the Surgical Section of the American Academy of Pediatrics. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:588–97. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(79)80145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marty TL, Matlak ME, Hendrickson M, et al. Unexpected death from enterocolitis after surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease. Pediatrics. 1995;96:118–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abbas Banani S, Forootan H. Role of anorectal myectomy after failed endorectal pull-through in Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1307–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90102-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elhalaby EA, Coran AG, Blane CE, et al. Enterocolitis associated with Hirschsprung’s disease: a clinical-radiological characterization based on 168 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:76–83. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90615-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langer JC. Persistent obstructive symptoms after surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease: development of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1458–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wildhaber BE, Pakarinen M, Rintala RJ, et al. Posterior myotomy/myectomy for persistent stooling problems in Hirschsprung’s disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:920–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.02.016. discussion 920–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niramis R, Watanatittan S, Anuntkosol M, et al. Quality of life of patients with Hirschsprung’s disease at 5–20 years post pull-through operations. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2008;18:38–43. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1038325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster W. Aganglionic megacolon in piebald-lethal mice. Arch Pathol. 1974;97:111–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosoda K, Hammer RE, Richardson JA, et al. Targeted and natural (piebald-lethal) mutations of endothelin-B receptor gene produce megacolon associated with spotted coat color in mice. Cell. 1994;79:1267–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baynash AG, Hosoda K, Giaid A, et al. Interaction of endothelin-3 with endothelin-B receptor is essential for development of epidermal melanocytes and enteric neurons. Cell. 1994;79:1277–85. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brizzolara A, Torre M, Favre A, et al. Histochemical study of Dom mouse: a model for Waardenburg-Hirschsprung’s phenotype. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1098–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagahama M, Ozaki T, Hama K. A study of the myenteric plexus of the congenital aganglionosis rat (spotting lethal) Anat Embryol (Berl) 1985;171:285–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00347017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Genc A, Taneli C, Turkdogan P, et al. Does high-pressure carbon dioxide insufflation facilitate mucosal dissection in transanal endorectal pull-through? A rabbit model. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:583–5. doi: 10.1007/s00383-003-0981-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Swenson O, Bill AH., Jr Resection of rectum and recto-sigmoid with preservation of sphincter for benign spastic lesions producing megacolon: an experimental study. Surgery. 1948;24:212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lui VC, Cheng WW, Leon TY, et al. Perturbation of hoxb5 signaling in vagal neural crests down-regulates ret leading to intestinal hypoganglionosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1104–15. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crone SA, Negro A, Trumpp A, et al. Colonic epithelial expression of ErbB2 is required for postnatal maintenance of the enteric nervous system. Neuron. 2003;37:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breau MA, Pietri T, Eder O, et al. Lack of beta1 integrins in enteric neural crest cells leads to a Hirschsprung-like phenotype. Development. 2006;133:1725–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.02346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li JC, Mi KH, Zhou JL, et al. The development of colon innervation in trisomy 16 mice and Hirschsprung’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:16–21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leffler A, Wedel T, Busch LC. Congenital colonic hypoganglionosis in murine trisomy 16—an animal model for Down’s syndrome. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9:381–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1072288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schuchardt A, D’Agati V, Larsson-Blomberg L, et al. RET-deficient mice: an animal model for Hirschsprung’s disease and renal agenesis. J Intern Med. 1995;238:327–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakatsuji T, Ieiri S, Masumoto K, et al. Intracellular calcium mobilization of the aganglionic intestine in the endothelin B receptor gene–deficient rat. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:1663–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Won KJ, Torihashi S, Mitsui-Saito M, et al. Increased smooth muscle contractility of intestine in the genetic null of the endothelin ETB receptor: a rat model for long segment Hirschsprung’s disease. Gut. 2002;50:355–60. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.3.355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dembowski C, Hofmann P, Koch T, et al. Phenotype, intestinal morphology, and survival of homozygous and heterozygous endothelin B receptor–deficient (spotting lethal) rats. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:480–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(00)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipman NS, Wardrip CL, Yuan CS, et al. Familial megacecum and colon in the rat: a new model of gastrointestinal neuromuscular dysfunction. Lab Anim Sci. 1998;48:243–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]