Abstract

The best method to mobilize PBSCs in patients with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) is uncertain. We hypothesized that PBSC mobilization using an intensive chemotherapy regimen would improve outcomes after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT) in NHL patients at high risk for relapse. Fifty NHL patients were prospectively allocated to intense mobilization with high-dose etoposide plus either high-dose cytarabine or CY if they were ‘high risk’ for relapse, whereas 30 patients were allocated to nonintense mobilization with CY if they were ‘standard risk’ (all patients, ±rituximab). All intensely mobilized patients were hospitalized compared with one-third of nonintensely mobilized patients. The EFS after ASCT was the same between the two groups, but overall survival (OS) was better for intensely mobilized patients (<0.01), including the diffuse large B-cell subgroup (P<0.04). We conclude that the intense mobilization of PBSCs in patients with NHL is more efficient than nonintense mobilization, but with greater toxicity. The equalization of EFS and superiority of OS in patients intensely mobilized to those nonintensely mobilized suggests that a treatment strategy using intensive chemotherapy for mobilization may be improving NHL outcomes after ASCT.

Keywords: mobilization therapy, auto-SCT, in vivo purging, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Introduction

Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (ASCT)is the treatment of choice for relapsed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL).1 ASCT strategies are now focusing on optimizing the mobilization of autologous PBSCs, minimizing tumor contamination of the PBSC product, maximizing the cytoreduction of endogenous tumor cells in the patient and ameliorating the toxicity of high-dose therapy. We hypothesized that the use of an intensive and effective antilymphoma regimen used for mobilization might improve outcomes following ASCT by reducing the tumor burden before transplant and might also provide an in vivo purging effect on the stem cell product. We have recently shown that 6 g/m2 of CY combined with 2 gm/m2 of etoposide (CE)and filgrastim (G-CSF)produced a high response rate in patients with multiple myeloma and relapsed/high-risk NHL while mobilizing 18.3 million CD34 cells per kg in a median of one apheresis procedure.2 This was accomplished, however, at the expense of a 3.5-week hospitalization and a 2% treatment-related mortality.

Most PBSC mobilizing regimens for NHL utilize CY (with or without rituximab)without the expectation that the chemotherapy used will significantly treat residual lymphoma. Our group has already tested and published a mobilizing regimen for AML using high doses of etoposide and cytarabine (EA)with excellent efficiency of mobilizing autologous PBSCs.3 We applied EA, with rituximab (EAR), in those NHL patients known to be CD20 positive, to high-risk NHL patients started to undergo PBSC mobilization and ASCT. The use of EAR to mobilize PBSCs has proven safe and effective in patients with mantle cell lymphoma as per Cancer and Leukemia Group B protocol 59909.4 Our hypothesis was that intense mobilization therapy would efficiently mobilize autologous PBSCs while improving the EFS of high-risk NHL patients following ASCT. We now report a retrospective analysis of NHL patients prospectively undergoing ASCT with the cyclophosphamide-carmustine-etoposide (CBV)regimen allocated by physician choice either to standard CY mobilization of PBSCs or to intense mobilization of PBSCs.

Materials and methods

Eligibility

Patients between the ages of 18 and 69 years were eligible for study enrollment, provided they had histologically documented NHL as well as the following: (1) chemotherapy-sensitive relapse of NHL (partial or complete second responses; any histology); (2) partial response or less to initial NHL chemotherapy (primary induction failure); and (3)first complete response to induction chemotherapy if affected by mantle cell lymphoma, intravascular lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma or peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Other eligibility criteria included the following: no known hypersensitivity to murine products; negative HIV serology; neither pregnant nor nursing; left ventricular ejection fraction ≥40%; serum creatinine ≤2 mg/100 ml; and signed, informed consent. Patients were excluded for symptomatic meningeal or parenchymal brain lymphoma and medical conditions requiring the chronic use of corticosteroids. Patients positive for hepatitis B surface antigen and/or hepatitis C antibody were excluded if the total bilirubin was >2 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), the aspartate aminotransferase was > 3 times the ULN, and/or a liver biopsy showed greater than grade 2 fibrosis.

On-study procedures

At the time of study enrollment, patients underwent the following procedures: history and physical examination, assessment of performance status, laboratory studies including a complete blood count, differential and platelet count, serum electrolytes, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, calcium, liver chemistries, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), serologies for hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV, urine or serum B-HCG in women of childbearing age, electrocardiogram, echocardiogram or multigated nuclear cardiac scintogram, chest radiograph, lumbar puncture (if aggressive histology), computer tomography scan or magnetic resonance images of chest/abdomen/pelvis (positron emission tomographic imaging was not required)and a unilateral bone marrow aspirate and biopsy with cytogenetic analysis. All patients had tissue biopsy demonstration of NHL.

Treatment

Eligible patients enrolled in this prospective trial to examine the outcomes of ASCT using the CBV conditioning regimen. The method of mobilizing PBSC was not protocol specified. Nonprotocol-specified decisions were prospectively and uniformly made with regard to the method of PBSC mobilization. Patients considered ‘standard risk’ for relapse received 4 gm/m2 cyclophosphamide intravenously (i.v.)(dose reduced to 2.5 gm/m2 for serum creatinine ≥ 1.5 mg/100 ml)on day 1 and G-CSF 5 µg/kg subcutaneously (s.c.)daily (beginning from day 4). The G-CSF dose was increased to 10 µg/kg s.c. beginning from day 9 and continued daily until the completion of PBSC collection. In the first 20 patients, the PBSC product was ex vivo purged with a combination of B-cell or T-cell MoAbs plus human complement.5,6 Thereafter, the PBSCs were in vivo purged with rituximab 375 mg/m2 if the patient had a CD20-positive B-cell NHL.7,8 Mesna was given at a dose 120% of the CY dose to prevent hemorrhagic cystitis. Leukapheresis was started when the WBC count reached 10 000/µl or greater.2 Eighteen liters of blood was processed per procedure. The CD34 cell dose target was 5 million/kg, with a minimum goal of 2 million/kg to proceed to ASCT. In patients with a CD34 cell dose of less than 2 million/kg, the colony-forming unit GM (CFU-GM)per kg needed to be ≥20 × 104/kg to proceed with ASCT.2

In patients designated ‘high risk’ for relapse, the mobilizing regimen was CE either with or without rituximab, EA or EAR. The ‘high-risk’ status was given to those patients who never achieved complete remission with their primary NHL therapy (primary induction failure), had a first complete remission duration less than 1 year, had a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)level of ≥ 500 IU/l at diagnosis, had two or more extranodal sites of NHL at diagnosis and/or were in any complete or partial response of mantle cell, central nervous system, intravascular or peripheral T-cell NHL histologies. CE was CY 600 mg/m2 i.v. over 1 h twice daily for 10 doses on days 1–5 (total dose 6000 mg/m2)and etoposide 2000 mg/m2 i.v. over 4h once on day 5.2 EA was etoposide 40 mg/kg i.v. over 96 h on days 1–4 of therapy and cytarabine 2gm/m2 i.v. over 2 h twice a day for 8 doses on days 1–4.3,4 Cytarabine dose modification was performed on the basis of the daily serum creatinine, as previously reported.9 In CD20-positive patients, after conclusion of the cohort undergoing ex vivo purging with MoAbs, rituximab was added to CE or EA as in vivo purging.7,8 Rituximab was given at a dose of 375 mg/m2 i.v. on days 6 and 13 of the mobilizing regimen. G-CSF was given s.c. (5 µg/kg)daily beginning from day 14 until the conclusion of the PBSC collection. The leukapheresis procedures and CD34 cell dose targets were the same as with the ‘standard-risk’ patients.

Most patients received the same conditioning regimen for ASCT, CBV: carmustine 15 mg/kg (maximum dose, 550 mg/m2) i.v. over 1 h on day −6; etoposide 60 mg/kg i.v. over 4 h on day −4; and CY 100 mg/kg i.v. over 3h on day −2.10 The infusion of autologous PBSCs i.v. occurred on day zero. Mesna was given (120 mg/kg)i.v. over 24 h beginning with the CY infusion to prevent hemorrhagic cystitis.

Supportive care

Because of the intensity of this PBSC mobilization program, severe myelosuppression was expected. Patients therefore received filgrastim (G-CSF)as well as bacterial (fluoroquinolone)and fungal (fluconazole or other azole) prophylaxis during the neutrophil nadirs of CE ± rituximab or EA/EAR. Patients receiving mobilization therapy with cyclophosphamide ± rituximab received fluoroquinolones and G-CSF during their neutropenic period. All patients received Pneumocystis carinii prophylaxis (trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole double strength twice daily 2 days per week)and Varicella zoster prophylaxis (acyclovir 200 mg three times daily)starting with PBSC mobilization chemotherapy. Packed RBC transfusions were given if the hematocrit was less than 26%; platelet transfusions were given if the platelet count was < 10000/ul in patients low risk for bleeding.11 Febrile neutropenia and transfusion support were managed as per the University of California, San Francisco institutional guidelines. High-dose prednisone (0.5 mg/kg twice daily)was recommended for any patient felt to be experiencing carmustine pneumonitis with an expected 6-week course involving tapering doses of prednisone.12

Statistical analysis

This is a retrospective analysis of a prospective trial examining the outcomes of NHL patients undergoing ASCT with CBV conditioning. All patients received informed, written consent for participation in this study. No additional risks to study participants were incurred from this retrospective analysis. Differences in patient cohort demographics and baseline characteristics were analyzed by the Student’s t-test. Dichotomous variables were analyzed by the χ2 statistic. The primary end point of this retrospective study was EFS, with the secondary end point being overall survival (OS), on an intention-to-treat basis. EFS, OS, complete response and partial response were defined as per the International Working Group criteria for responses in NHL.13 Survival end points began with the date of the PBSC infusion. EFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Significant differences between groups needed to demonstrate P-values <0.05. The log-rank analysis was used to compare the survival outcomes of patient cohorts.

Results

Patient characteristics

Eighty patients were enrolled on the study between August 1999 and September 2005 (Table 1). The median age was 54 years. Sixty-five percent of patients were Ann Arbor stage IV at their initial diagnosis of NHL, with 57% demonstrating an elevated LDH at that time. Ninety-three percent of patients had B-cell histology (Table 2). Of the 60 patients whose graft did not undergo ex vivo purging, 56 (93%)were CD20 (+)and received IV rituximab as in vivo purging. Two of the 20 patients undergoing ex vivo purging also received IV rituximab as in vivo purging. Patients allocated to intense mobilization therapy were more likely to have an elevated LDH at diagnosis (Table 1)and were more likely to have a first CR under 1 year (Table 3). Patients allocated to intense mobilization therapy tended to have a higher International Prognostic Index score and to have received more therapies earlier (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter (units/range) | All patients | Intense mobilization | Nonintense mobilization | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 80 | 50 | 30 | |

| Age (median years) | 54 (21–69) | 55(23–69) | 54(21–68) | 0.64 |

| Female(%) | 36 | 36 | 37 | 0.95 |

| Histology (no.) | ||||

| B cell | 74 | 45 | 29 | 0.18 |

| T cell | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Stage (no.)a | ||||

| I | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.21 |

| II | 11 | 6 | 5 | |

| III | 14 | 10 | 4 | |

| IV | 52 | 34 | 18 | |

| ≥2 Extranodal sites (%)a | 35 | 36 | 28 | 0.44 |

| Bone marrow involved | 41 | 44 | 40 | 0.87 |

| CSF/CNS involved | 16 | 16 | 18 | 0.9 |

| Elevated LDH (%)a | 57 | 68 | 40 | 0.01 |

| ECOG performance status ≥2 (%)a | 16 | 21 | 7 | 0.12 |

| High-intermediate or high IPI score: no. (%)a | 22/58 (38) | 17/37(46) | 6/21(29) | 0.27 |

Abbreviations: CSF=cerebrospinal fluid; CNS= central nervous system; ECOG= Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IPI= International Prognostic Index; LDH =lactate dehydrogenase.

At the time of initial NHL diagnosis.

Table 2.

NHL histologies

| Histology | Number |

|---|---|

| Burkitt’s | 2 |

| Primary CNS | 3 |

| Follicular | 3 |

| Intravascular | 2 |

| Diffuse large B cells | 43 |

| Low grade—transformed | 9 |

| Mantle cell | 12 |

| Peripheral T cells | 4 |

| T-NK cell | 2 |

Abbreviations: CNS=central nervous system; NK =natural killer.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients by mobilization scheme

| Parameter | Intense mobilization | Nonintense mobilization | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 50 | 30 | |

| International prognostic index (%)a | 0.24 | ||

| Low | 27 | 56 | |

| Low-intermediate | 27 | 24 | |

| High-intermediate | 38 | 20 | |

| High | 8 | 0 | |

| ≥2 Extra-nodal sites (%)a | 36 | 30 | 0.6 |

| Primary induction failure (%)a | 56 | 40 | 0.34 |

| LDH >500 IU/l (number/total evaluable)a | 4/12 | 2/9 | 0.57 |

| First CR less than 1 year (number/total evaluable) | 16/28 | 6/21 | 0.04 |

| Median number of previous therapies (range) | 2 (1–5) | 2(1–6) | 0.05 |

| Mantle cell/primary CNS/intravascular/peripheral T-cell histology (%) | 38 | 13 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: CNS = central nervous system; CR =complete response; LDH=lactate dehydrogenase.

At the time of initial NHL diagnosis.

The salvage therapy just proximal to the mobilization therapy was not strictly defined. Patients allocated to nonintense and to intense mobilization both received a median of two cycles of salvage therapy (0–5)just before mobilization. In nonintense patients, the salvage therapy was (R)CHOP (n=9), ESHAP (n=4), other (n=12)and none (n=3). In intense patients, the salvage therapy was RCHOP (n=1), (R)ESHAP (n=5), (R)ICE (n=14), other (n=14)and none (n=5). Twelve of twenty five (48%) of nonintense patients achieved a complete response from their proximal salvage therapy compared with the 12 of 34 (35%)of intense patients (P=0.23).

Toxicity

The intense mobilization of PBSCs was more toxic than the nonintense mobilization of PBSCs (Table 4). All patients receiving intense mobilization required hospitalization, for a median of 24 days (19–37). Ten of thirty patients (33%) receiving nonintense mobilization were hospitalized for a median of 2 days (1–11), when hospitalized. The reasons for nonintensely mobilized patients to be hospitalized were as follows: medical or social reasons to deliver CY in the hospital (2); febrile neutropenia (3); intractable nausea/ vomiting (4); and cardiac tamponade (1). Patients allocated to intense mobilization therapy spent significantly more days with neutrophils under 500/µl and platelets under 20 000/µl while receiving significantly more platelet and RBC transfusions than patients allocated to nonintense mobilization therapy (Table 4). Hepatic and renal toxicity was mild and no difference was found when comparing the two mobilization schemes (Table 4).

Table 4.

Toxicity by mobilization regimen

| Parameter (units) | Intense mobilization | Nonintense mobilization | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 50 | 30 | |

| Treatment-related mortality (no.) | 0 | 0 | |

| Hospitalization (days) | 24 (19–37) | 0(0–11) | <0.01 |

| Neutrophils < 500/µl (days) | 11 (9–19) | 2(0–6) | <0.01 |

| Platelets <20000/µl (days) | 10 (2–22) | 0(0–6) | <0.01 |

| Platelet transfusions (no.) | 4 (1–14) | 0(0–2) | <0.01 |

| Red blood cell transfusions(U) | 4 (0–12) | 2(0–6) | <0.01 |

| Median maximum total bilirubin (mg/100 ml) | 1 (0.6–4.1) | 0.7(0.5–3.6) | 0.18 |

| Median maximum Alkaline Phosphatase (U/l) | 98(48–436) | 74(37–197) | 0.09 |

| Median maximum serum Creatinine (mg/100 ml) | 1.2(0.5–3) | 0.9(0.5–2.4) | 0.06 |

Abbreviation: CNS =central nervous system.

There were no treatment-related deaths from either intense or nonintense mobilization therapy. There were three treatment-related deaths after ASCT. There were two deaths due to carmustine pneumonitis (one nonintense mobilization and one EAR)and one death due to cardiomyopathy (EA). Two patients, both with nonintense mobilization, did not receive CBV and ASCT. One had an inadequate collection of PBSCs and autologous bone marrow. That patient instead received a second course of EAR with infusion of his PBSCs and bone marrow as cellular support. The second patient received high-dose carmustine at which time an enlarged cervical lymph node was noted. Biopsy of the lymph node revealed metastatic tongue cancer. The second patient did not receive the conditioning etoposide or CY but received an infusion of his PBSCs.

Engraftment

Intense PBSC mobilization yielded a greater number of CD34-positive cells in fewer apheresis procedures (Table 5). Not all collected PBSCs were infused on day zero of ASCT. The CD34 cell dose infused was left to the discretion of the patient’s attending physician, provided the CD34 cell dose was 5 million/kg or greater. Twice as many CD34 cells were infused into patients who underwent intense mobilization compared with those who underwent nonintense mobilization. Despite this difference in infused CD34 cell dose, there were no differences in myeloid engraftment (Table 5). One patient (who was mobilized with EA)required infusion of backup PBSCs for poor engraftment and subsequently had full engraftment. In the 20 patients who had ex vivo purging of their PBSCs with MoAbs and complement, the post-purge CD34 cell-dose yield was 61% (prepurge CD34 cell dose, median 7.2 million/kg (range 2.3–30 million/kg)and post-purge CD34 cell dose, median 4.9 million/kg (range 1.3–13 million/kg)). There was no difference in engraftment parameters comparing patients whose PBSC were ex vivo purged to those who had no ex vivo purging (Table 5).

Table 5.

PBSC yield and engraftment

| Parameter | Intense mobilization | Nonintense mobilization | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 50 | 30 | |

| Number of aphereses to reach CD34 cell dose target (no.) | 1(1–7) | 2(1–6) | <0.03 |

| CD34 cell dose yield (million/kg) | 15.1 (4.9–205.9) | 7.5(2.3–63.8) | <0.02 |

| CD34 cell dose infused (million/kg) | 10.3 (2.2–60) | 5.4(2.3–21.3) | <0.01 |

| Neutrophils ≥500/µl (day of ASCT) | +11 (9–18) | +11(9–23) | 0.37 |

| Platelets ≥20000/µl (day of ASCT) | +18 (8–117) | +14(8–4) | 0.43 |

| Platelet transfusions (no.) | 4 (1–30) | 3(0–14) | 0.13 |

| Ex vivo purge | No ex vivo purge | P-value | |

| Number | 20 | 60 | |

| Intense mobilization (no.) | 5 | 4 | 0.6 |

| CD34 cell dose infused (million/kg) | 4.9 (1.3–12.7) | 9.5(1.3–60) | <0.01 |

| Neutrophils ≥500/µl (day of ASCT) | +11 (9–17) | +11(9–23) | 0.9 |

| Platelets ≥20000/µl (day of ASCT) | +19 (10–74) | +16(8–117) | 0.8 |

| Platelet transfusions (no.) | 4 (0–11) | 4(1–30) | 0.45 |

Survival outcomes

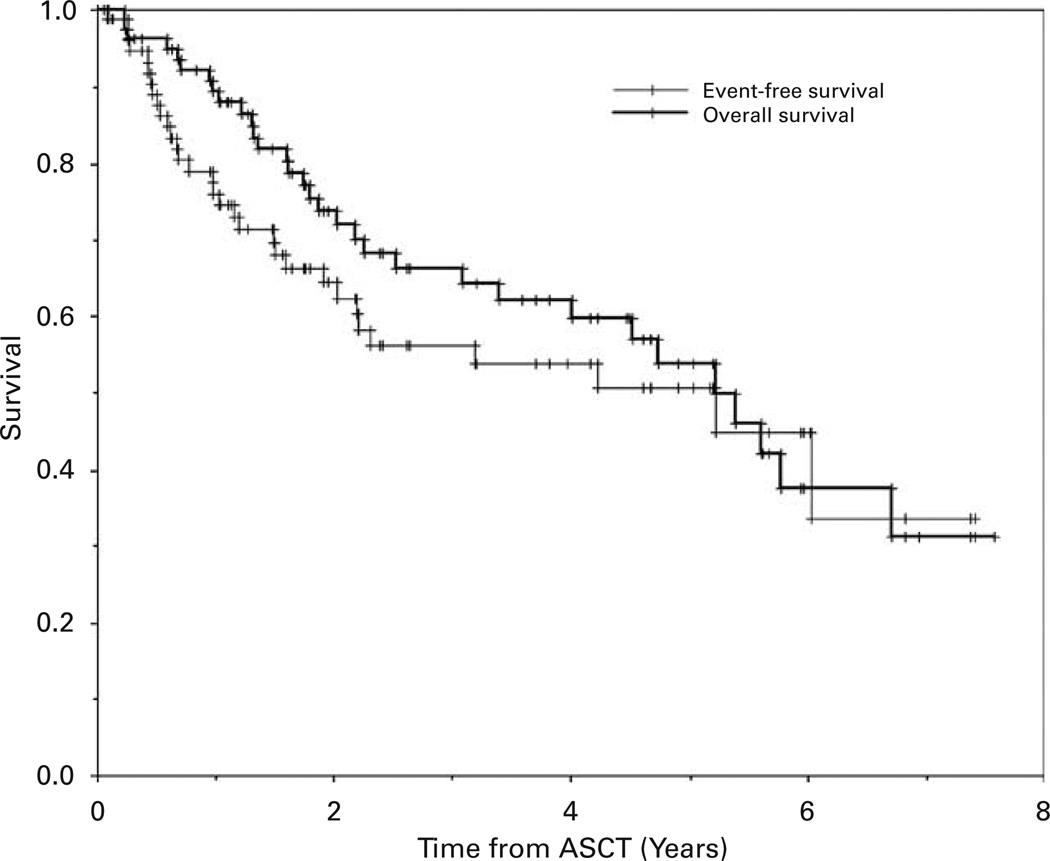

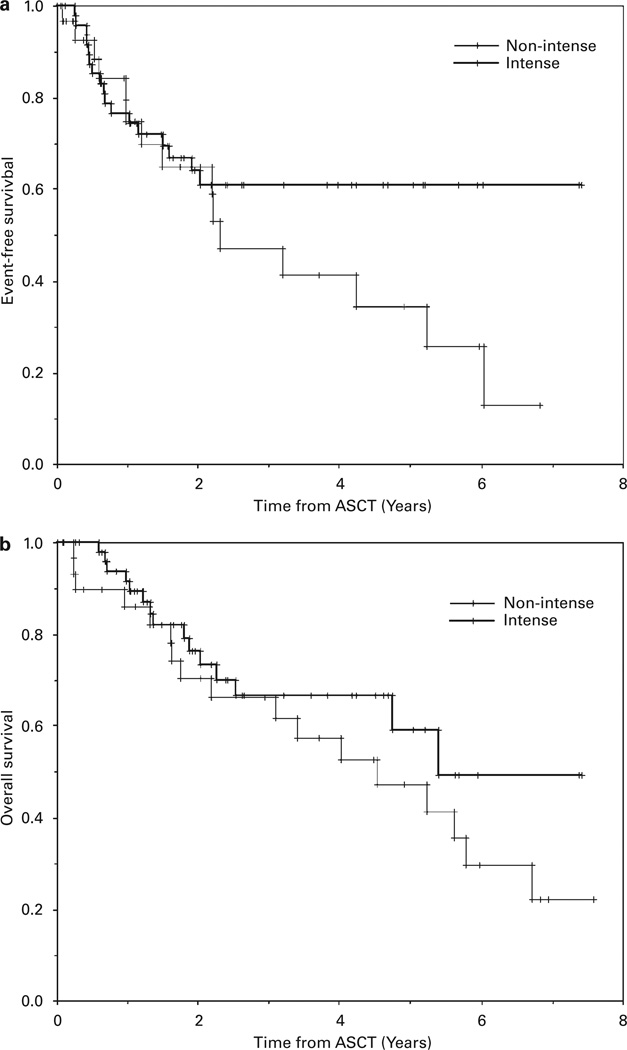

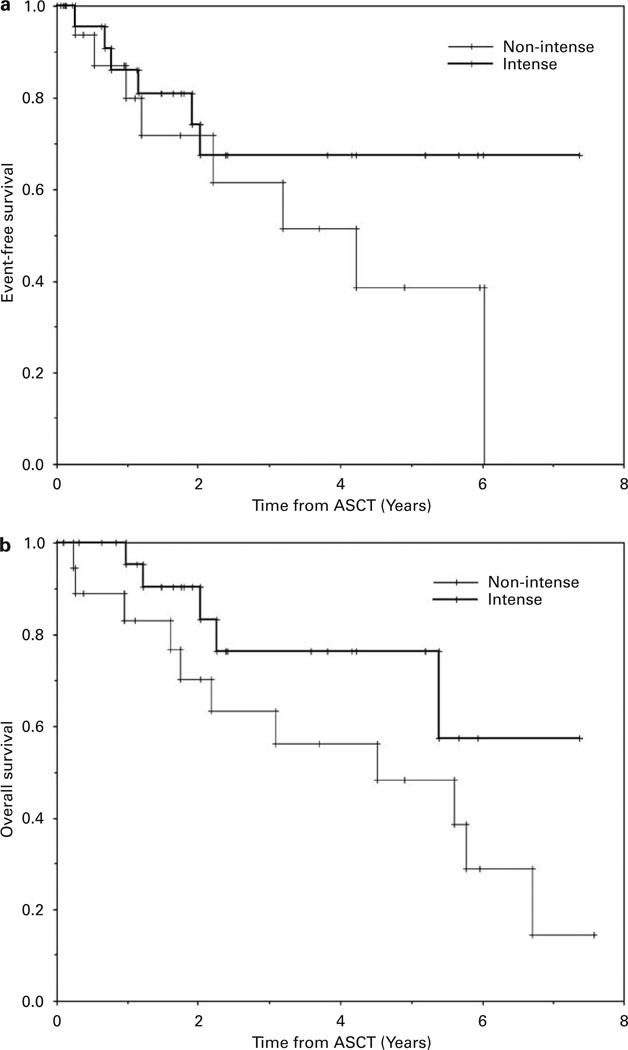

The median follow-up of survivors in this study is 2.5 years (range 0.1–7.6 years). The median EFS and OS of all enrolled patients were both 5.2 years (Table 6; Figure 1). There was no difference in the EFS comparing patients undergoing intense mobilization to nonintense mobilization of PBSCs, but the OS was better for patients undergoing intense mobilization (median OS, 5.4 vs 4.5 years, respectively, P<0.01)(Table 6; Figure 2). Likewise, in the subgroup of diffuse large B-cell NHL, there was no difference in EFS but a significantly better OS (P<0.04) in patients undergoing intense PBSC mobilization (Table 6 and Figure 3). There were no differences in EFS or OS comparing the subgroups of the major NHL histologies (diffuse large B-cell, transformed low grade or mantle cell) or whether or not ex vivo purging of the PBSC product was performed (data not shown).

Table 6.

Survival outcomes

| Group/subgroup | No. | Percent 4-year EFS (95% CI) |

Median EFS (years) |

P-valuea | Percent 4-year S (95% CI) |

Median OS (years) |

P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 80 | 54 (±13) | 5.2 | 62 (±12) | 5.2 | ||

| Mobilization | |||||||

| Intense | 50 | 61 (±15) | NR | 0.56 | 67 (±15) | 5.4 | <0.01 |

| Nonintense | 30 | 41 (±23) | 2.3 | 57 (±19) | 4.5 | ||

| Diffuse large B cells | |||||||

| Intense | 24 | 67 (±22) | NR | 0.96 | 76 (±20) | NR | <0.04 |

| Nonintense | 19 | 51 (±29) | 4.2 | 56 (±25) | 4.5 |

Abbreviations: OS=overall survival; CI=confidence interval; NR=not reached.

Log-rank analysis of Kaplan–Meier probabilities.

Figure 1.

The Kaplan–Meier probabilities of event-free survival and overall survival for all patients enrolled on study.

Figure 2.

The Kaplan–Meier probabilities of event-free survival (a)and overall survival (OS)(b)comparing those patients undergoing intense vs nonintense mobilization therapy. OS was better for patients undergoing intense mobilization therapy (P<0.01).

Figure 3.

The Kaplan–Meier probabilities of event-free survival (a)and overall survival (OS)(b)comparing patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma undergoing intense vs nonintense mobilization therapy. OS was better for patients undergoing intense mobilization therapy (P<0.04).

Discussion

The optimal method of PBSC mobilization for ASCT in patients with NHL is not yet established. Two major considerations are the degree of NHL contamination of the PBSC product and the efficiency of the PBSC mobilization procedure, but the mobilizing regimen may also contribute to overall outcomes through its direct antitumor effect. In our retrospective study, we found that the intense mobilization of PBSCs yielded a more efficient PBSC product (a greater CD34 cell dose in fewer aphereses), but at the expense of a prolonged hospital stay. Furthermore, intense mobilization of PBSCs did not produce better engraftment when used following CBV conditioning compared with nonintense mobilization. More importantly, the patients who received intensive chemotherapy mobilization on the basis of their physician’s assessment that they were at high-risk of relapse had outcomes that were at least as good as those felt to be at standard risk of relapse. This suggests that the intense mobilization of PBSCs in high-risk NHL patients helped to overcome adverse prognostic factors.

Whether a relapse of NHL occurs following high-dose therapy/ASCT is due to residual NHL in the patient or due to contaminating NHL cells in the PBSC product has not yet been settled.14–17 Our study was not designed to resolve this question. However, the equivalent EFS rates between those NHL patients undergoing intense PBSC mobilization, deemed to be at high risk for NHL relapse, compared with those NHL patients receiving nonintense mobilization therapy, felt to be at a lower risk for relapse, suggests that intense PBSC mobilizing therapy contributed to treatment success in one or both of these ways. It is unlikely that the salvage therapy patients received proximal to mobilization normalized the outcomes in these two risk groups, as both groups received the same number of cycles of salvage therapy and there was there was no difference in the complete response rates to this salvage therapy between groups. In fact, there was a trend toward more complete responses to the proximal salvage therapy in the nonintense group, which, if anything, would bias toward favorable outcomes in this group.

There is significant cost and morbidity associated with the intense mobilization of PBSCs in NHL patients: a 3.5-week hospital stay. Fortunately, there were no treatment-related deaths due to intense mobilization in the 50 patients in this study. Patients undergoing intense mobilization required, as expected, more blood products and spent more time severely neutropenic compared with those undergoing nonintense mobilization. In a sense, intense mobilization therapy can be thought of as the first of a tandem ASCT for NHL.

To date, at least seven pilot studies have explored the use of tandem ASCT for NHL.18–24 These studies mostly involve NHL mixed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients whose disease status ranges from primary refractory to sensitive or refractory relapse to high-risk first complete remission. A total of 74–76% of patients completed both transplants.22,24 In contrast, 100% of our intensely mobilized patients were able to undergo ASCT. Significant complications of tandem ASCT include a treatment-related mortality rate of 8–16%22–24 and, in one study, a veno-occlusive disease of liver rate of 13%.18 We had a total treatment-related mortality of 4% (all after ASCT)and no veno-occlusive disease of liver. One tandem ASCT study tested the tandem ASCT concept in patients with aggressive NHL with 2–3 age-adjusted International Prognostic Index risk factors in first complete remission of their lymphoma.20 The 3-year EFS and OS were 47 and 50%, respectively, and the authors concluded tandem ASCT to be no better than a single ASCT compared with historical controls within the same study group with similar risk factors. In our patients with diffuse large B-cell NHL and worse characteristics (including primary induction failure and relapsed patients), the 4-year EFS and OS were 67 and 76%, respectively. There are too many differences between the patients and their treatments in these studies for us to speculate whether our two-step, intense mobilization approach is the same, better or worse than a tandem ASCT for NHL. We feel, however, that the high doses of chemotherapy utilized to mobilize PBSC in our intensely mobilized patients likely had an important impact on their ultimate outcomes.

The contribution of purging NHL from the PBSC graft to improving outcomes in NHL is not at all clear. Our initial intention was to explore ex vivo purging of the grafts with MoAbs and complement.5,6 The MoAbs were no longer available after the first 20 patients were enrolled. We therefore switched to the emerging idea of in vivo purging with rituximab for those individuals with CD20 (+) tumors. Data at the time was showing great success in purging contaminating NHL cells from grafts by this technique in individuals with informative PCR for the rearranged bcl-1/IgH and bcl-2/IgH transcripts.7,8 We did not follow patients prospectively for the effectiveness of in vivo purging in the graft nor for minimal residual disease. How much in vivo rituximab contributed to NHL outcomes cannot be answered in this retrospective study.

It is intriguing that OS was significantly improved in intensely mobilized patients, but EFS was not. However, the EFS curves plateau after 2 years in the intensely treated patients but continuously fall in the nonintensely mobilized patients. This suggests, but does not prove, that the intense mobilization strategy cures more NHL patients than the nonintense strategy. Perhaps this improved EFS outcome is not evident by log-rank analysis due to the small number of patients in each subgroup, yet the translation of this benefit nonetheless became evident in the OS curves.

In summary, mobilizing PBSC with intense therapy is more efficient than mobilizing PBSCs with nonintense therapy, but with substantially more toxicity, in patients with NHL. The equivalency of EFS and improvement in OS in intensely mobilized patients after ASCT with CBV compared with nonintensely mobilized patients is indirect evidence that the intense mobilization strategy is better, as our intensely mobilized patients had risk features suggesting a greater chance of relapse following ASCT. Our trial is not definitive, as a prospective randomization between mobilization schemes did not occur. A comparative trial of mobilization strategies is warranted in high-risk NHL patients who are appropriate candidates for ASCT.

References

- 1.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, Somers R, Van der Lelie H, Bron D, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damon L, Rugo H, Tolaney S, Navarro W, Martin T, III, Ries C, et al. Cytoreduction of lymphoid malignancies and mobilization of blood hematopoietic progenitor cells with high doses of cyclophosphamide and etoposide plus filgrastim. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2006;12:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linker CA, Ries CA, Damon LE, Sayre P, Navarro W, Rugo HS, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia in first remission. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:50–57. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Damon L, Johnson J, Niedzwiecki D, Cheson BD, Hurd D, Bartlett N, et al. Immuno-chemotherapy (IC)and autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT)for untreated patients (pts)with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): CALGB 59909. Blood. 2006;108:774a. (abst 2737) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Negrin RS, Kusnierz-Glaz CR, Still BJ, Schrober JR, Chao NJ, Long GD, et al. Transplantation of enriched and purged peripheral blood progenitor cells from a single apheresis product in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood. 1995;85:3334–3341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negrin RS, Kiem HP, Schmidt-Wolf IG, Blume KG, Clearly ML. Use of the polymerase chain reaction to monitor the effectiveness of ex vivo tumor cell purging. Blood. 1991;77:654–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flinn IW, O’Donnell PV, Goodrich A, Vogelsang G, Abrams R, Noga S, et al. Immunotherapy with rituximab during peripheral blood stem cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:628–632. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arcaini L, Orlandi E, Alessandrino EP, Iacono I, Brusamolino E, Bonfichi M, et al. A model of in vivo purging with rituximab and high-dose AraC in follicular and mantle cell lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34:175–179. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith GA, Damon LE, Rugo HS, Ries CA, Linker CA. High-dose cytarabine dose modification reduces the incidence of neurotoxicity in patients with renal insufficiency. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:833–839. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.2.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Horning SJ, Negrin RS, Chao NJ, Hu WW, Long GD, et al. Influence of preparatory regimen and source of hematopoietic cells on outcome of autotransplantation for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1996;2:76–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebulla P, Finazzi G, Marangoni F, Avvisati G, Guliotta L, Tognani G, et al. The threshold for prophylactic platelet transfusions in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche Maligne dell’Adulto. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1870–1875. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao TM, Negrin RS, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, Johnston LJ, Shizuru JA, Taylor TL, et al. Pulmonary toxicity syndrome in breast cancer patients undergoing BCNU-containing high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2000;6:387–394. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, Shipp MA, Fisher RI, Connors JM, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244–1253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deisseroth AB, Zu Z, Claxton D, Hanania EG, Fu S, Ellerson D, et al. Genetic marking shows that Ph+ cells present in autologous transplants of chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML)contribute to relapse after autologous bone marrow in CML. Blood. 1994;83:3068–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanania EG, Kavanagh J, Hortobagyi G, Giles RE, Champlin R, Deisseroth AB. Recent advances in the application of gene therapy to human disease. Am J Med. 1995;99:537–552. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachier CR, Giles RE, Ellerson D, Hanania EG, Garcia-Sanchez F, Andreeff M, et al. Hematopoietic retroviral gene marking in patients with follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1999;32:279–288. doi: 10.3109/10428199909167388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alici E, Björkstrand B, Treschow A, Aints A, Smith CI, Gahrton G, et al. Long-term follow-up of gene-marked CD34+ cells after autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Cancer Gene Ther. 2007;14:227–232. doi: 10.1038/sj.cgt.7701006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitoussi O, Simon D, Brice P, Makke J, Scrobohaci ML, Bibi Triki T, et al. Tandem transplant of peripheral blood stem cells for patients with poor-prognosis Hodgkins’s disease or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1999;24:747–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballestrero A, Clavio M, Ferrando F, Gonella R, Garuti A, Sessarego M, et al. High-dose chemotherapy with tandem autologous transplantation as part of the initial therapy for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:1007–1013. doi: 10.3892/ijo.17.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haioun C, Mounier N, Quesnel B, Morel P, Rieux C, Beaujen F, et al. Tandem autotransplant as first-line consolidative treatment in poor-risk aggressive lymphoma: a pilot study of 36 patients. Ann Oncol. 2001;12:1749–1755. doi: 10.1023/a:1013578523579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le Gouill S, Moreau P, Morineau N, Harousseau JL, Milpied N. Tandem high-dose therapy followed by autologous stem-cell transplantation for refractory or relapsed high grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma with poor prognosis factors: a prospective pilot study. Haematologica. 2002;87:333–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed T, Rashid K, Waheed F, Kancherla R, Qureshi Z, Hoang A, et al. Long-term survival of patients with resistant lymphoma treated with tandem stem cell transplant. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:405–414. doi: 10.1080/10428190400019826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glossmann JP, Staak JO, Nogova L, Diehl V, Scheid C, Kisro J, et al. Autologous tandem transplantation in patients with primary progressive or relapsed/refractory lymphoma. Ann Hematol. 2005;84:517–525. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-1011-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papadopoulos KP, Noguera-Irizarry W, Wiebe L, Hesdorffer CS, Garvin J, Nichols GL, et al. Pilot study of tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation with a novel combination of regimens in patients with poor risk lymphoma. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;36:491–497. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]