INTRODUCTION

Total visual field sensitivity has become an accepted outcome measure for treatment trials in retinitis pigmentosa (RP).1-3 Field sensitivity is measured at numerous locations throughout the retina on an automated perimeter, typically the Humphrey Field Analyzer (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Dublin, CA). Sensitivity at all points within the field is summed, and this total sensitivity is recorded at regular intervals, typically annually. Annual rates of change are low, varying from 5% to 15% depending on a range of factors including genetic type, and the repeat variability of field measurements is high 4, necessitating large sample sizes followed over several years to evaluate a potential intervention.

Total visual field sensitivity masks local variations in rates of change in different regions of the field. It is well established, for example, that sensitivity in the macula can remain high until late in disease progression. Thus locations within the macula are likely to show a lower than average rate of decline. Locations in the periphery may have low or unmeasurable sensitivity, leading to a floor effect in the assessment of progression. Other regions may have a higher than average rate of change. We and others have identified a region on frequency domain optical coherence tomography (fdOCT) images of the retina where there is a transitional zone between relatively healthy retina, where the inner segment ellipsoid zone (EZ) remains intact, and advanced degeneration, where there is no EZ.5, 6, 7 Furthermore, we have shown that there is a corresponding transition between relatively good sensitivity central to this zone and relatively severe sensitivity loss peripheral to the zone.5, 8 The width of the EZ appears to be a sensitive and reliable measure of progression. 5, 9, 10 These findings raise the possibility that the rate of sensitivity loss might be higher in the transitional zone than in other regions. The goal of the present paper is to test this hypothesis by comparing the rate of sensitivity decline in transitional zone locations identified by fdOCT to the rates of sensitivity decline in the macula and mid-periphery.

METHODS

Patients

All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of UT Southwestern Medical Center and the research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. After informed consent was obtained, measures were obtained from 44 patients (ages 8 to 30 yrs) with xlRP due to a mutation in the RPGR gene (Table 1). Patients were a subset of participants in a 4-year randomized placebo-controlled study of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00100230)11. Inclusion criteria included a cone 31 Hz ERG amplitude > 1.0 μV at baseline. A single eye (typically the left) was selected for the field and OCT analyses. Visual field sensitivity was measured with the 30-2 grid (spot size 5) on the Humphrey visual field analyzer. Visual field sensitivity was measured twice per eye prior to the baseline visit to minimize practice effects.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics on Y2 of study (first visit with fdOCT)

| ID# | AGE (Yr 2) | RPGR Mutation Class | GROUP | Lens OD | Lens OS | VA OD (LogMAR) | VA OS (LogMAR) | 30 Hz amp (μV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G101 | 12 | Exon1-14, Missense | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 16.5 |

| G116 | 11 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 3.8 |

| G118 | 16 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 8.2 |

| G121 | 13 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 3.8 |

| G123 | 17 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | PSC | PSC | 0.3 | 0.3 | 1.2 |

| G124 | 12 | Exon1-14, Missense | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 3.7 |

| G127 | 15 | ORF15, Nonesense | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 24.5 |

| G131 | 15 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 5.9 |

| G132 | 29 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 15.5 |

| G134 | 17 | Exon1-14, Nonsense | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 9.2 |

| G135 | 33 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 7.6 |

| G142 | 16 | ORF15, Nonesense | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 30.7 |

| G144 | 17 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31.2 |

| G147 | 11 | Exon1-14, Splice site | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| G149 | 20 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 8.1 |

| G150 | 9 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 12.0 |

| G171 | 26 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | PSC | PSC | 0.4 | 0.5 | 5.6 |

| G185 | 9 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 11.5 |

| G186 | 16 | Exon1-14, Splice site | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 2.4 |

| G187 | 11 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.9 |

| G191 | 19 | Exon1-14, Nonsense | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.4 |

| G198 | 10 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 16.7 |

| G201 | 17 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 18.2 |

| G208 | 13 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 2.8 |

| G215 | 27 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | DHA | PSC* | PSC | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.8 |

| G216 | 33 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 11.1 |

| G229 | 25 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.9 |

| G234 | 18 | Exon1-14, Splice site | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 17.0 |

| G247 | 9 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 3.9 |

| G248 | 13 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13.4 |

| G250 | 10 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 16.2 |

| G253 | 30 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | IOL | IOL | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.2 |

| G255 | 9 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 15.1 |

| G256 | 9 | Exon1-14, Splice site | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 5.6 |

| G257 | 24 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 7.3 |

| G259 | 12 | Exon1-14, Nonsense | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 2.0 |

| G270 | 28 | Exon1-14, Splice site | DHA | N | N | 0.3 | 0.3 | 5.9 |

| G273 | 13 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 1.6 |

| G293 | 10 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 41.7 |

| G296 | 31 | Exon1-14, Nonsense | DHA | IOL | IOL | 0.3 | 0.4 | 1.2 |

| G302 | 27 | Exon1-14, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 4.9 |

| G319 | 26 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | PSC* | PSC* | 0.5 | 0.6 | 3.6 |

| G330 | 18 | ORF15, Frameshift | DHA | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28.7 |

| G339 | 19 | ORF15, Frameshift | Placebo | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 25.5 |

DHA = docosahexaenoic acid; PSC = posterior subcapsular cataract; N = nuclear cataract; IOL = intraocular lens

AREDS grading < 2

Fields were measured at baseline and on 4 consecutive annual visits. Beginning with the third visit (Year 2), 9 mm (approximately 30 degrees) horizontal midline fdOCT scans were obtained yearly with a Heidelberg Spectralis HRA +OCT (Heidelberg, Germany). Automatic real time registration (ART) was used with an average of 100 scans. All scans had a quality index of greater than 25 dB. Repeat scans were captured with the aid of automatic registration to ensure the same scan placement on each test. Manual segmentation was aided by previously published routines (Hood et al, 2009). Three boundaries were identified (Fig. 1): the boundary between Bruch's membrane and choroid, the boundary between photoreceptor outer segments (OS) and RPE, and the inner segment (IS)/OS junction (EZ). For all scans, the nasal and temporal borders of the EZ were defined as the locations where the thickness of the OS layer declined to zero. The width of the EZ was defined as the horizontal distance between these two locations.

Figure 1.

FdOCTs from a representative patient on three annual visits. The left column shows SLO images with visual field sensitivity superimposed. The right column shows segmented horizontal scans through the fovea, with yellow highlighting the EZ band, blue indicating the outer segment/RPE boundary and purple highlighting the base of the RPE/Bruch's membrane. Long vertical lines indicate the edges of the EZ on year 2 (first fdOCT scan). The superimposed numbers in the line scan on the right represent the mean of the two field sensitivity values from just above and just below the horizontal midline indicated in the SLO image on the left. For each patient visit, four regions were established on Year 2 and followed on successive visits. The “Macula” was the average of 5 locations within the central 10 degrees, “inside EZ” was the average of the nasal and temporal pair just inside the EZ edge on Year 2, “outside EZ” was the average of the nasal and temporal pair just outside the EZ edge on Year 2, and “periphery” (not shown) was all points between 10 and 30 degrees.

Based on the segmented scans on Year 2, two pairs of nasal and temporal field locations were selected for each patient. One nasal and temporal pair was just inside the EZ edge and the other was just outside the EZ edge. The rate of change at these locations was compared to the rates of change for the macula (5 points within central 10 degrees) and the mid-periphery (70 points between 10 and 30 degrees). Macula, inside EZ, outside EZ, and peripheral locations were always selected from the Year 2 fdOCT scan. Sensitivity values from each zone/location were averaged to provide a single measure for each location on each patient-visit. Thus, although the four locations were determined from the fdOCT in Year 2, the values were available for the identical locations from fields obtained on all five annual visits.

Paired t-tests were used to evaluate differences in field sensitivity at “inside EZ” and “outside EZ” locations. A two-way within-subjects Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to determine the significance of differences in rates of decline at different locations.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the age of each patient, the RPGR mutation class, lens status, visual acuity and cone 30-Hz ERG amplitude.

Figure 1 shows an example of horizontal midline scans from patient G101. Year 2 of the 4-year study was the first year for which fdOCT was available. Scans are shown with superimposed segmentation lines, with yellow highlighting the EZ band, blue indicating the outer segment/RPE boundary and purple highlighting the base of the RPE/Bruch's membrane. The low reflectance region between the red internal limiting membrane (red band) and the outer plexiform layer (mauve band) consists of the outer nuclear layer and Henle fiber layer, which cannot be distinguished without specialized imaging techniques 12. Long vertical lines indicate the horizontal extent of the EZ band at Year 2; i.e. the lines are placed where the EZ band becomes indistinguishable from the RPE. Inside the vertical lines are relatively healthy photoreceptors as indicated by near normal outer segment thickness, while the outer segments are not detectable outside the vertical lines.

EZ width was measurable in 40 out of 44 patients (91%). One patient had edges of the EZ peripheral to the region scanned and three patients did not show an intact EZ zone within the region scanned. At Year 2, there was a significant relationship between the width of the EZ band and the age of the patient (F(1,39)=11.99; p=0.0013). Over 2 years of follow up, the average decline in the diameter of the EZ among all patients was 1.7 degrees (492 μm).

Sensitivity values at locations just above and below the horizontal meridian in a representative patient are shown in Figure 1 superimposed on the SLO images in the left column. The averages of the values above and below the midline are shown superimposed on the fdOCT scans in the right column. Points indicated as “macula” were from locations within the central 10 degrees. The points labeled “inside EZ” were the closest points internal to the edge of the EZ at Year 2; for the patient shown in Figure 11 this is 7.5 degrees nasal and temporal to the fovea. The points labeled “outside EZ” were the closest points external to the edge of the EZ; for Figure 1 this is 12.5 degrees temporal to the fovea (the nasal point was nasal to the disk and thus not shown on the figure). Mid-peripheral points are also not shown on the figure, but comprise all points eccentric to 10 degrees. The spacing of test locations was standard 6 degrees in both horizontal and vertical directions, offset by 3 degrees from the foveal in both directions. Therefore, the locations shown in Figure 1 are (±3°, ±3°), (±9°, ±3°), and (+15°, ±3°) -- in addition to the fovea (0°, 0°). Consistent with previous reports8, the EZ width decreases over years in this patient. As a consequence, the field locations identified as “inside EZ” in each patient become progressively closer to the edge of the EZ, while those identified as “outside EZ’ become progressively further away.

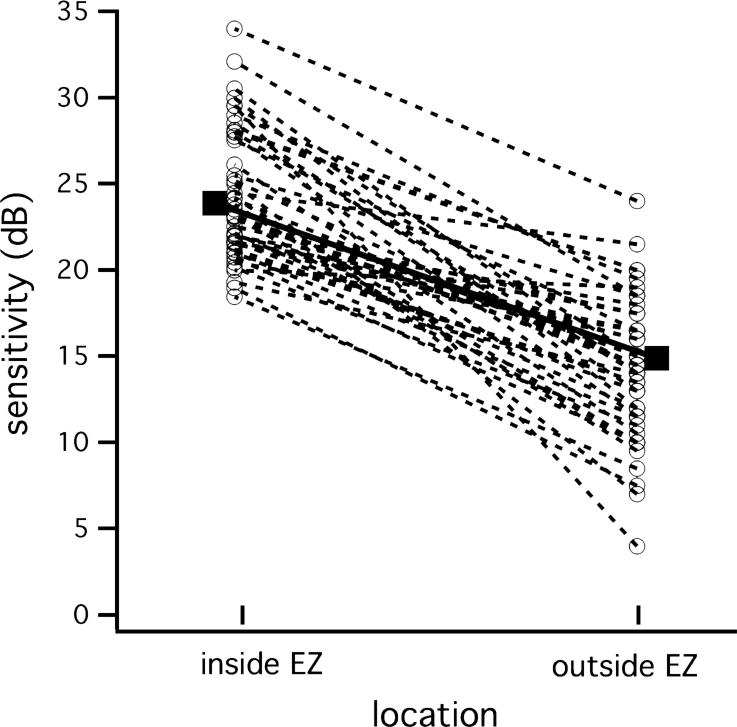

Figure 2 confirms that the transition zone encompassing “inside EZ” and “outside EZ” is a region of abrupt change in field sensitivity. Plotted are “inside EZ” and “outside EZ” sensitivity measures for each patient on Year 2. The solid squares indicate the means for all 40 patients with measurable EZ. The average decrease in field sensitivity between “inside EZ” and “outside EZ” was 8.9 dB (t = 11.11; p < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Difference in sensitivity inside and outside the edge of the EZ for each patient (dashed lines) on the first fdOCT measurement (Year 2). Solid circles and solid line shows an 8.9 dB average decrease in field sensitivity across the edge of the EZ.

Figure 3 shows the annual decline in field sensitivity over 4 years in 40 patients for each of the locations defined by fdOCT on Year 2. Sensitivity declined at the highest rate just inside (0.84 ± 0.1 dB/year; 19%) and just outside (0.92 ± 0.1 dB/year; 19%) the edge of the EZ. By comparison, sensitivity in the macula and mid-periphery declined at slower rates of 0.38 ± 0.1 dB/year (9%) and 0.61 ± 0.07 dB/year (13%). To determine whether these differences in rates of decline were significant, we performed a two-way within-subjects ANCOVA (Table 2). As expected, there was a significant effect of location, with “macula” differing from “inside EZ” and “mid-periphery” differing from “outside EZ”. Of more interest were the interaction effects, with the mean sensitivity in the “macula” changing at a different rate than mean sensitivity for the “inside EZ”, and mean sensitivity in the “outside EZ” changing over time at a different rate than mean sensitivity in the “mid-periphery”. Simple linear regression was then used to obtain estimates of the individual slopes. Average rates with 95% confidence intervals and significance levels are shown in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Yearly sensitivity decline at different field locations. Macula includes locations within the central 10° while periphery is locations eccentric to 10°. Inside EZ and outside EZ locations were based on the fdOCT on Year 2.

Table 2.

| Rate (dB/y) [95%-c.i.] | P-value (comp. to zero slope) | Comparison of slopes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Macula | −0.38 [−0.81, +0.05] | 0.081 | *** P=0.0009 |

| Inside EZ | −0.84 [−1.24, −0.45] | <0.0001 *** | |

| Outside EZ | −0.92 [−1.35, −0.49] | <0.0001 *** | * P=0.018 |

| Mid-periphery | −0.61 [−1.18, −0.04] | 0.037 * |

Figure 4 shows the change in “outside EZ” sensitivity plotted against the change in EZ width over the two years for which both measures were available. The vertical dashed line shows no change in EZ width. All but one patient lies to the left of the vertical line; that is, 39/40 patients (98%) with RPGR mutations showed a decrease in EZ width over a two-year interval. The horizontal dashed line shows no change in visual field sensitivity at the “outside EZ” location. Ten patients showed either no change or increase in sensitivity over 2 years. The remaining 30 (75%) showed varying degrees of loss that correlated modestly with the magnitude of the change in EZ width. The diagonal (solid line) indicates equal loss in each measure. There is a tendency for patients with greater change in EZ width to show greater % change in sensitivity in the “outside EZ” region, but the variability inherent in the field measure adds considerable noise to the relationship.

Figure 4.

Change in field sensitivity at the outside EZ location relative to change in EZ width. Results are for 2 years of follow up. Vertical dashed line shows no change in EZ, while horizontal dashed line shows no change in field sensitivity at the outside EZ location. Diagonal line reflects equal change in each parameter.

For comparison, the 2-year-change in “macula” sensitivity is plotted against the change in EZ width in Fig 5. Most of the patients show little change in macula sensitivity over 2 years, with only the patients with the largest decrease in EZ width showing a decline.

Figure 5.

Change in field sensitivity in the macula relative to change in EZ width. Results are for 2 years of follow up. Vertical dashed line shows no change in EZ, while horizontal dashed line shows no change in macula field sensitivity. Diagonal line reflects equal change in each parameter.

DISCUSSION

As a physical measure with low repeat variability, fdOCT has strong potential for following disease progression in clinical studies of RP. With fdOCT, anatomically distinct layers of the outer retina can be visualized.13, 14, 15-17 The thickness of these layers in the transition zone between healthy and severely affected retina provides a possible model of disease progression.18, 19 The earliest change seen in the transition zone with fdOCT is a decrease in the thickness of the OS layer, followed by decreases in the ONL.18, 20 With further loss in vision, the OS region disappears completely. This disappearance of the OS region does not occur until 9 to 10 dB of sensitivity has been lost as measured with static automated perimetry.5, 9 Thus, the point at which the OS region disappears is a marker of the edge of the healthiest region of the visual field, meaning the location at which visual sensitivity shows a precipitous change.5 The loss of OS in fdOCT is reflected in a loss of the highly reflective inner segment ellipsoid zone (ISe or EZ). The EZ band (also known as inner segment [IS]/OS band) is thought by some13 to be due to light scattered by the mitochondria of the ellipsoid region of the IS, and by others21 to be due to the change in refractive indices of the IS and OS. In either case, by convention, the OS thickness is measured between the EZ band and the proximal border of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Thus, when the EZ band disappears (i.e., is no longer discernible from the RPE border), the OS thickness is by definition zero. Although regions outside the EZ band may not be blind, they nevertheless require at least an order of magnitude more light for detection.

The ONL may also prove useful for measuring progression 22. It is clear from Figure 1 that ONL loss is also occurring in the areas of greatest field loss. We previously showed that annual change in ONL thickness just met a 5% significance level (P = 0.044), primarily because the measurement variability was substantially higher than for EZ width 10. Furthermore, the relationship to cell body loss to field loss has not been well worked out and the ONL segmentation is difficult because of the presence of the Henle fiber layer in the macula. With specialized techniques, however, 12 it may be possible to use ONL thickness or extent as a measure of progression, especially in area of advanced disease.

The results in the present study of 44 patients with RPGR-mediated XLRP extend previous results from an overlapping subset of 28 patients with genetically undefined XLRP9. The transition zone surrounding the edge of the EZ separates relatively health regions from severely diseased regions and could be identified in 91% of patients. We found a modest but significant relationship to patient age. The rate of progression, averaging 246 μm/ year (0.85°/year) was comparable to that reported previously and roughly twice the test-retest variability.9, 10 Here we show that there is a functional consequence of this shrinking EZ in that visual sensitivity declines faster in the transition zone than in other regions of the retina. Thus the anatomical outcome measure (EZ) reflects a function outcome (field sensitivity), but doesn't suffer the weaknesses documented in the Introduction.

The visual fields measured in this study were obtained with static perimetry. As an outcome measure, sensitivity is typically summed across the measured locations and shows an exponential decline over time. Previously reported rates of decline in xlRP are consistent with the overall rate of decline reported here 11, 23-25. However, we have identified an anatomical marker for identifying active regions that primarily drive the decline in total sensitivity. It is interesting to speculate how this might affect kinetic perimetry. It is well established that fields to size V stimuli may be stable for years but progress faster once a critical age is reached 26. The findings of the present paper imply that it is not critical age but critical loss of EZ that is determining field diameter. The best isopters for matching the area of the EZ to the area of the kinetic field would probably be Goldmann III4e, given the approx. 10 dB drop in sensitivity across the edge of the EZ. Clearly, rates of progression for kinetic perimetry are more complex than for static perimetry, and may only approximate exponential decline at specific stages of progression 26.

A weakness of the present study is that fdOCT measures were only available for the last three years in this prospective study. Another weakness is that EZ was based on horizontal midline scans rather than volume scans. However, we have also shown that EZ width and EZ area are highly correlated.10

The present findings reinforce the relationship between the anatomical change reflected in the EZ and the functional change reflected in visual field sensitivity. The visual field was divided into four zones. Within the macula, there was relatively little change over time as sensitivity is likely mediated by the healthiest photoreceptors. Within the periphery, there is relatively little change over time as most photoreceptors are severely affected. The measured rate of decline is further impacted by a floor effect, as stimuli in some peripheral regions are not seen at the highest stimulus strength available. The most dynamic region of the field is within the transition zone as measured by fdOCT. Sensitivity at locations just inside and outside the edge of the EZ changes most rapidly. These findings suggest that sensitivity to change in visual field measurements is hampered by averaging across the field and suggest possible new strategies for monitoring disease progression in clinical trials in retinitis pigmentosa.

Acknowledgements

Genetic mutation analysis was conducted by colleagues at the Human Genetics Center, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX (Drs. Stephen Daiger, Lori Sullivan, and Sara Bowne), at the University of Michigan Kellogg Eye Center, Ann Arbor, MI (Drs. Anand Swaroop and John Heckenlively), and at McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, Quebec, Canada (Dr. Robert Koenekoop).

Supported by NIH EY09076 and Foundation Fighting Blindness

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

None of the authors has any proprietary/financial interest to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoffman DR, Locke KG, Wheaton DH, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Amer J Ophthalmol. 2004;137:704–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berson EL, Rosner B, Sandberg MA, et al. Clinical trial of docosahexaenoic acid in patients with retinitis pigmentosa receiving vitamin A treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(9):1297–305. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.9.1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berson EL, Rosner B, Sandberg MA, et al. Clinical trial of lutein in patients with retinitis pigmentosa receiving vitamin A. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(4):403–11. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seiple W, Clemens CJ, Greenstein VC, et al. Test-retest reliability of the multifocal electroretinogram and Humphrey visual fields in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Doc Ophthalmol. 2004;109:255–72. doi: 10.1007/s10633-005-0567-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hood DC, Ramachandran R, Holopigian K, et al. Method for deriving visual field boundaries from OCT scans of patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Biomedical optics express. 2011;2(5):1106–14. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.001106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson SG, Aleman TS, Sumaroka A, et al. Disease boundaries in the retina of patients with Usher syndrome caused by MY07A gene mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1886–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hood DC, Lin CE, Lazow MA, et al. Thickness of receptor and post-receptor retinal layers in patients with retinitis pigmentosa measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography (fdOCT). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2936. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangaswamy NV, Patel HM, Locke KG, et al. A comparison of visual field sensitivity to photoreceptor thickness in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(51):4213–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birch DG, Locke KG, Wen Y, et al. Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography measures of outer segment layer progression in patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(9):1143–50. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ramachandran R, Zhou L, Locke KG, et al. A Comparison of Methods for Tracking Progression in X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa Using Frequency Domain OCT. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2013;2(7):1–9. doi: 10.1167/tvst.2.7.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffman DR, Hughbanks-Wheaton DK, Pearson SN, et al. Four-year placebo-controlled trial of docosahexaenoic acid in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (DHAX trial) A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmology. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lujan BJ, Roorda A, Knighton RW, Carroll J. Revealing Henle's fiber layer using spectral domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(3):1486–92. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spaide RF, Curcio CA. Anatomical correlates to the bands seen in the outer retina by optical coherence tomography: literature review and model. Retina. 2011;31(8):1609–19. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e3182247535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez EJ, GHermann B, Povazay B. Ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography and pancorrection for cellular imaging of the living human retina. Optics Express. 2008;16:11083–94. doi: 10.1364/oe.16.011083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hood DC, Lin CE, Lazow MA, et al. Thickness of receptor and post-receptor retinal layers in patients with retinitis pigmentosa measured with frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(5):2328–36. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wen Y, Klein M, Hood DC, Birch DG. Relationships Among Multifocal Electroretinogram Amplitude, Visual Field Sensitivity, and SD-OCT Receptor Layer Thicknesses in Patients with Retinitis Pigmentosa. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2012 doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sandberg MA, Brockhurst RJ, Gaudio AR, Berson EL. The association between visual acuity and central retinal thickness in retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(9):3349–54. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hood DC, Lazow MA, Locke KG, et al. The transition zone between healthy and diseased retina in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(1):101–8. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacobson SG, Aleman TS, Sumaroka A, et al. Disease boundaries in the retina of patients with Usher syndrome caused by MYO7A gene mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50(4):1886–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazow MA, Hood DC, Ramachandran R, et al. Transition zones between healthy and diseased retina in choroideremia (CHM) and Stargardt disease (STGD) as compared to retinitis pigmentosa (RP). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(13):9581–90. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kocaoglu OP, Lee SJ, Jonnal RS. Imaging cone photoreceptors in three dimensions and in time using ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography with adaptive optics. Biomedical optics express. 2011;2:748–63. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.000748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobson SG, Aleman TS, Sumaroka A, et al. Disease Boundaries in the Retina of Patients with Usher Syndrome Caused by MYO7A Gene Mutations. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 2008;50(4):1886–94. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Birch DG, Anderson JL. Yearly rates of rod and cone functional loss in retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod degeneration. Vision Science and its Applications; OSA Technical Digest Series. 1993;3:334–7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandberg MA, Rosner B, Weigel-DiFranco C, et al. Disease course of patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to RPGR gene mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1298–304. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoffman DR, Locke KG, Wheaton DH, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(4):704–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Massof RW, Dagnelie G, Benzschawel T, et al. First order dynamics of visual field loss in retinitis pigmentosa. Clin Vision Sci. 1990;5(1):1–26. [Google Scholar]