Abstract

Background

Insufficient evidence exists to support obesity prevention in pediatric primary care.

Objectives

To test a theory-based behavior modification intervention delivered by trained pediatric primary care providers for obesity prevention.

Methods

Efficacy trial with cluster randomization (practice level) and a 12-session 12-month sweetened-beverages decrease intervention or a comprehensive dietary and physical activity intervention, compared to a control intervention among children ages 8–12 years.

Results

A low recruitment rate was observed. The increase in body mass index z-score (BMIz) for the 139 subjects (11 practices) randomized to any of the two obesity interventions (combined group) was less than that of the 33 subjects (5 practices) randomized to the control intervention (−0.089, 95%CI: −0.170 to −0.008, p=0.03) with a −1.44 kg weight difference (95%CI: −2.98 to +0.10 kg, p=0.095). The incidences of obesity and excess weight gain were lower in the obesity interventions, but the number of subjects was small. Post hoc analyses comparing the beverage only to the control intervention also showed an intervention benefit on BMIz (−0.083, 95%CI: −0.165 to −0.001, p=0.048).

Conclusions

For participating families, an obesity prevention intervention delivered by pediatric primary care clinicians, who are compensated, trained and continuously supported by behavioral specialists, can impact children’s BMIz.

Trial registration number

Keywords: behavioral economics, beverages, cluster analysis, office visits, primary health care

Introduction

While the prevalence of childhood obesity appears to have stabilized recently in the United States,1 it continues to be an important public health concern and novel approaches to prevention are necessary to reverse the trends. School-based obesity prevention interventions have, in some cases, been successful,2 but community-based,3–6 home-based, and primary care practice-based interventions have led to mixed results.8–14 The pediatric primary care setting has several advantages for the prevention of excess weight gain: pediatric practitioners have a culture of prevention, have an ongoing relationship with children, often from birth to young adulthood, and are seen by families as a trusted source of health information.15 Furthermore, it is often in the pediatric primary care setting that excess weight gain is first detected through changes in body mass index (BMI) percentiles. However, most pediatric primary care providers are not trained, supported, or compensated to deliver theory-based behavior modification interventions for the prevention of excess weight gain.16

Therefore, the goal of this study was to test if pediatric primary care providers can deliver, as part of their clinical practice, an intervention, similar to interventions successful in the research settings, in a way that can impact BMI z-score (BMIz). To maximize the chances of success of this efficacy study, providers were trained, supported, and compensated and families were carefully selected based on their chances of success. In addition to the control intervention, two forms of active intervention were delivered: one focused on a single behavior and one focused on multiple behaviors, because it is unknown if, in the context of prevention, addressing several behaviors may be too overwhelming for families to implement. The single behavior intervention focused on changing beverage choices, as it is one of the behaviors thought to have a significant impact on weight in children.17

Methods

“Smart Steps” was a cluster-randomized trial of two interventions aimed at preventing increase in BMIz compared to a control intervention of the same intensity unrelated to weight. Randomization was at the practice level to decrease the risk of intervention contamination and stratified by characteristics of the practice patient population: more or less than 50% of patients on Medicaid. Pediatric primary care practices were selected within The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) Care Network through the CHOP Practice-Based Research Network and practices in the Philadelphia area outside of the CHOP network (two private independent multi-provider practices, one in a boarding school staffed by another academic institution, and one part of another care network), based on interest and availability. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of CHOP and other institutions involved with subjects and it was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov.

Subjects

As a prevention study, subjects were selected with a BMI between the 75th and the 95th percentile based on their last clinic visit when weight and height were measured.18 At the baseline visit, some subjects were measured to be outside of this range, but were included, as they were still considered at risk for excess weight gain, based on their BMI at the previous clinic visit. Other inclusion criteria were: age 8.0–12.9 years, consulting at the selected practice in the past three years, and consuming an average of at least 4 oz. of sugar sweetened beverages (see definition in Table 1) per day, to insure relevance of the beverage-only intervention. Exclusion criteria were serious physical or psychiatric conditions or medications potentially interfering with nutrition or physical activity, as determined by the primary care pediatrician. Home-schooled patients were excluded, so that the control intervention (bullying prevention) would be relevant to those randomized to it.

Table 1.

Features of Each Smart Steps Intervention Arm

| Obesity Interventions | Control Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Beverages-Only Intervention | Multiple-Behavior Intervention | Friendship Making intervention | |

| Behavioral Objectives | |||

|

| |||

|

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Content

| |||

| Knowledge |

|

|

|

| Skills |

|

|

|

| Motivation, Support, and Goal Setting |

|

|

|

| Experience |

|

|

|

| Intervention Context and Support to Interventionists-Clinicians |

|

|

|

|

| |||

| Contact Schedule

| |||

|

|

|

|

“We Can!” is weight management program for children available from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute19

Procedures

After identification of potentially eligible subjects from medical records, a letter co-signed by the research team and the primary care clinician was sent to families and followed by up to three phone calls. Because randomization by practice occurred before subjects’ recruitment, to decrease the risk of recruitment bias, study staff was masked to which practice the subjects they called were part of. The telephone script and letter were relevant to all of the three intervention arms. After informed consent and assent from the children, parents were asked to return a three-day diet record for the child (two weekdays and one weekend day) to screen out families less likely to be compliant and to assess the sweetened beverages intake inclusion criteria.

Eligible subjects were scheduled for the first measurement visit which took place at the practice or subjects’ home before the intervention, as did the six, twelve, and, for some subjects, 24 months visits. Unlike the intervention, these visits were performed by study staff trained in the measurement methods and regularly tested for intra- and inter-observer reliability which ranged from .90 to .99. Demographic characteristics were assessed by questionnaire; weight (Scaletronix, Carol Stream, IL) and height (Holtain, Crymych, UK) were measured by portable equipment; skinfold thickness was measured (0.1 mm) at the triceps, biceps, sub-scapular, and supra-iliac sites with a skinfold caliper (Holtain, Crymych, UK).

Interventions

A 5-hour behavioral-specialist-led training workshop, providing continuing medical education credits but no financial compensation, was held for the clinicians, who were then certified to deliver the arm of the intervention to which their practice was randomized to. The conceptual framework, aims and activities for each session, clinician’s manuals, self-monitoring booklets, behavioral contracts, educational materials, and, when available, electronic medical record data entry fields to document session adherence were reviewed and role play of select sessions were conducted. The theory-based (behavioral economics), family-based, culturally- and developmentally-appropriate intervention consisted of twelve 15 – 25 minute clinician, child, and at least one parent or guardian encounters over 12 months. Children earned points, based on session attendance and goal achievements, which they could exchange for small prizes selected from a study catalogue. The clinical practice or clinician was compensated a $35 flat fee for each competed session. Regular conference calls of the clinicians with the research team took place and behaviorally-trained research staff was available to support the clinical staff in implementing the intervention. Details on the content of the beverage-only (modified from part of the “We Can!” program),19 multiple behavior (changes in multiple aspects of diet, physical activity, and sedentary activity), and control (bullying prevention)20 interventions are provided in Table 1.

Data Analyses

Analyses were performed using Stata 10 (Statacorp, College Station, TX) with two-sided tests and a p value below 0.05 as the criterion for statistical significance. BMI was calculated as weight (in kg) divided by height (in meter) squared and transformed into z-scores using sex and age references.18 The a priori defined primary outcome was a difference in BMIz between baseline and 12 months and the primary hypothesis was a comparison of subjects randomized to either of the two obesity prevention interventions (combined obesity interventions group) to subjects randomized to the control intervention. Secondary outcomes selected a priori included: incidence of obesity, changes in unadjusted BMI and changes in skinfold thickness. Due to scientific developments since the design of the study, unadjusted weight gain and excess weight gain, as defined by Stevens, et al.,21 (more than 3% change in BMI above the expected age change among non-obese subjects or incident obesity) were also used as secondary outcomes. Also based on the new findings, analyses were repeated using follow-up measurement adjusted for baseline measurement.22 The a priori secondary hypothesis was a comparison between each obesity intervention and the control intervention at 24 months, but, due to the large amount of missing data at 24 months, this secondary hypothesis was instead tested at 12 months. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used to account for non-independence of observation within clusters using the “xtgee” command in Stata with an exchangeable working correlation structure. Randomization was found to be successful by comparing age, sex, race, ethnicity, and baseline BMIz between intervention groups, and therefore, unadjusted analyses were used. Analyses were first performed for completers only, then, because analysis of completers tends to overestimate the effect of obesity interventions,23 all analyses were repeated after multiple imputations of missing data (100 imputations by analyses) based on intervention group, age, sex, race, ethnicity, and baseline BMIz, as well as changes from baseline to 6 and 24 months BMIz when available. The imputation was conducted using the “ice” command in Stata, which implements a multiple imputation chained-equations approach for imputation (see details in Stata documentation).

Sample size calculation was based on the secondary hypothesis at 24 months to detect a clinically significant effect size between each obesity intervention group and the control intervention of 0.40 (corresponding to a difference between groups of 0.28 SD in BMIz changes in from baseline to 24 months), assuming a drop-out rate of 20%, an intra-cluster correlation coefficient of 0.012 (observed in preliminary studies), a type-one error value of 0.05 and a type-two error value of 0.80. This yielded a sample size of 504 subjects in 24 practices for the secondary hypothesis. While the study was originally powered on the secondary hypothesis at 24 months, this report focuses on the primary hypothesis (combined obesity prevention intervention groups vs. control group at 12 months), for which the sample size calculation was 350 subjects in 17 practices.

Results

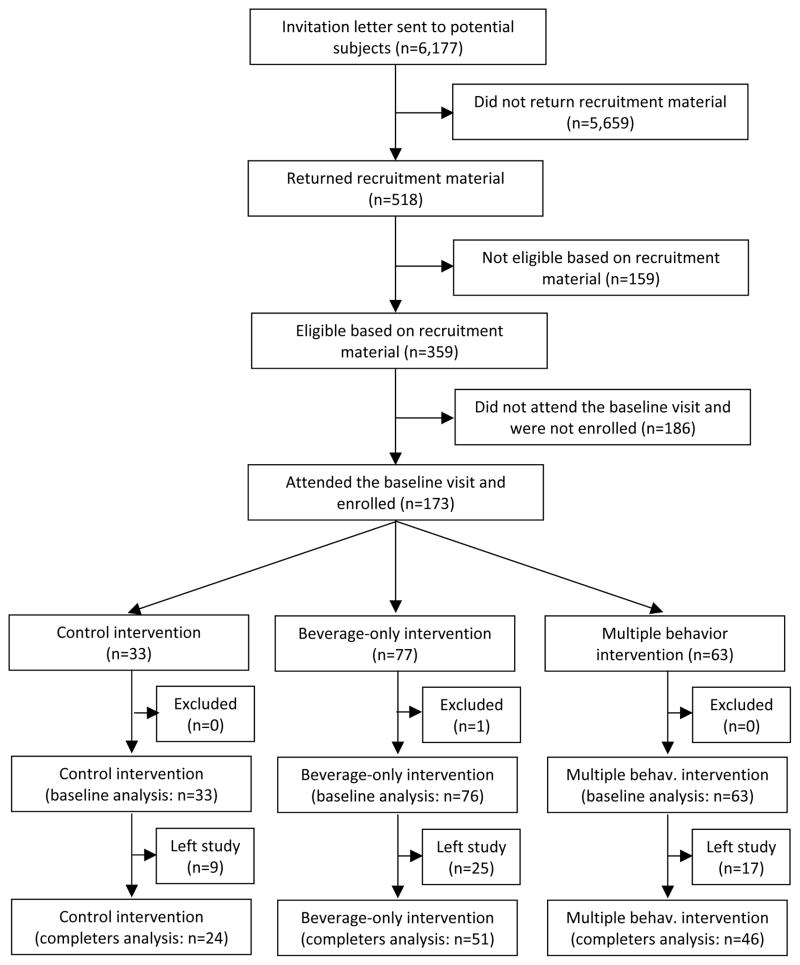

Due to major difficulties and delays in enrolling practices, the recruitment goals were not achieved and the study was substantially underpowered with only 14 practices and 172 subjects (Figure 1, Table 2) after exclusion of one subject in the beverage-only intervention group who developed type 1 diabetes (an exclusion criteria associated with significant weight loss), during the course of the intervention. The number of subjects per practice varied from one to 28. Six practices were randomized to the beverage-only intervention, four to the multiple-behavior intervention, and five to the control intervention. Study subjects attended a median of 8 sessions without statistically significant differences between groups. The intervention was conducted by eight pediatricians, two nurse practitioners, twelve nurses, one social worker, and four medical assistants. Fidelity to the intervention was insured by observation of selected intervention sessions by the behavioral team. The dropout rate was not statistically different between groups (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Subjects flow diagram

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Study Subjects at Baseline and 12-Month Follow-Up by Intervention Group

| Control intervention | Obesity interventions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control intervention group n (baseline)=33 n (12-month)=24 |

Combined beverage-only and multiple behaviors interventions group n (baseline)=139 n (12-month)=97 |

Beverage-only intervention group n (baseline)=76 n (12-month)=51 |

Multiple behavior intervention group n (baseline)=63 n (12-month)=46 |

||||

| Mean and standard deviation or n and % | Mean and standard deviation or n and % | Difference with control, p-valuea | Mean and standard deviation or n and % | Difference with control, p-valuea | Mean and standard deviation or n and % | Difference with control, p-valuea | |

| Age, y (SD) | 10.8 (1.4) | 10.7 (1.4) | 0.60 | 10.8 (1.4) | 0.79 | 10.7 (1.3) | 0.45 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 15 (45%) | 75 (54%) | 0.42 | 39 (51%) | 0.52 | 36 (57%) | 0.22 |

| Race | 0.46 | 0.88 | 0.21 | ||||

| White, n (%) | 23 (70%) | 68 (49%) | 48 (63%) | 20 (32%) | |||

| Black, n (%) | 8 (24%) | 65 (47%) | 25 (33%) | 40 (63%) | |||

| Multiple or other, n (%) | 2 (6%) | 6 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (5%) | |||

| Ethnicity, % Latino/Hispanic, n (%) | 3 (9%) | 8 (6%) | 0.50 | 3 (4%) | 0.27 | 5 (8%) | 0.81 |

| Baseline weight, kg (SD) | 49.2 (12.2) | 46.8 (11.1) | 0.27 | 46.8 (11.9) | 0.31 | 46.8 (10.2) | 0.32 |

| 12-m weight, kg (SD) | 57.8 (14.9) | 52.3 (11.2) | 0.03 | 52.4 (12.5) | 0.04 | 52.3 (9.8) | 0.04 |

| Baseline height, m (SD) | 148.2 (11.3) | 146.5 (11.0) | 0.40 | 146.2 (12.1) | 0.34 | 146.9 (9.7) | 0.55 |

| 12-m height, m (SD) | 155.1 (11.3) | 152.8 (10.1) | 0.26 | 151.9 (11.0) | 0.08 | 153.7 (9.1) | 0.33 |

| Baseline BMI,b kg/m2 (SD) | 22.0 (2.9) | 21.5 (2.6) | 0.28 | 21.5 (2.7) | 0.37 | 21.4 (2.6) | 0.28 |

| 12-m BMI,b kg/m2 (SD) | 23.7 (3.6) | 22.2 (2.9) | 0.04 | 22.4 (3.0) | 0.09 | 22.0 (2.7) | 0.03 |

| Baseline BMI z-score, SD (SD) | 1.34 (0.38) | 1.22 (0.50) | 0.11 | 1.21 (0.54) | 0.08 | 1.22 (0.47) | 0.21 |

| 12-m BMI z-score, SD (SD) | 1.44 (0.44) | 1.17 (0.58) | 0.02 | 1.18 (0.62) | 0.03 | 1.16 (0.53) | 0.03 |

| Baseline obese,c n (%) | 7 (21%) | 25 (18%) | 0.65 | 14 (18%) | 0.71 | 11 (17%) | 0.65 |

| 12-m obese,c n (%) | 9 (38%) | 15 (15%) | 0.02 | 8 (15%) | 0.05 | 7 (15%) | 0.05 |

| Baseline skinfolds,d mm (SD) | 68.1 (28.4) | 62.5 (21.8) | 0.21 | 63.7 (21.4) | 0.36 | 61.0 (22.5) | 0.16 |

| 12-m skinfolds,d mm (SD) | 68.9 (25.5) | 59.5 (19.3) | 0.06 | 61.6 (18.8) | 0.16 | 57.1 (19.9) | 0.03 |

Test statistics performed taking into account the cluster design

BMI: Body mass index

BMI at or above the 95th percentile of a reference population 18

Sum of triceps, biceps, sub-scapular, and supra-iliac skinfold thickness

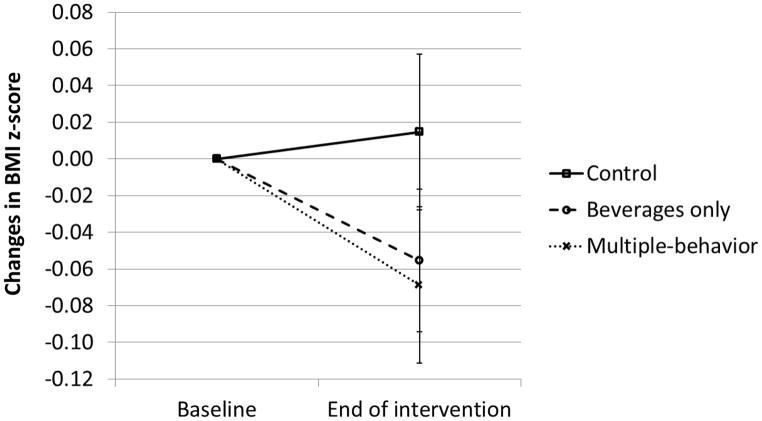

Results for completers and after imputations are presented in Table 2, 3 and Figure 2. For the primary analysis and outcome, using both completers only and imputations, subjects randomized to either of the two obesity prevention interventions (combined obesity interventions group) had less increase in BMIz than subjects randomized to the control intervention. Incidences of obesity and of excess weight gain were also lower in the combined obesity interventions group. Among completers, in the control group, 6 out of 24 subjects (25%) presented with excess weight gain, as compared to 5 out of 97 (5%) in the combined obesity interventions group. Changes in BMI were significant in the analyses of completers, but not after multiple imputations. A weight difference of about 1.5 kg was observed between the combined obesity interventions and the control groups, but this did not reach statistical significance, nor did the difference in the sum of four skinfolds.

Table 3.

Obesity Prevention vs. Control Intervention Groups Comparisons of the Anthropometric Changes or Incidence of Obesity or Excess Weight Gain over the 12-Month Study among Completers and After Multiple Imputations

| Analysis of completers only | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity prevention interventions (combined, n=97 completers) compared to control intervention (reference group, n=24 completers) | Beverages-only intervention (n=51 completers) compared to control intervention (reference group) | Multiple-behaviors intervention (n=46 completers) compared to control intervention (reference group) | |||||||

| Difference in change or odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | Difference in change or odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | Difference in change or odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | |

| BMIa z-score, SD (difference in change) | −0.087 | −0.172 to −0.002 | 0.05b | −0.068 | −0.158 to +0.022 | 0.14 | −0.100 | −0.183 to −0.017 | 0.02 |

| BMI,a kg/m2 (difference in change) | −0.54 | −1.03 to −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.45 | −0.96 to +0.06 | 0.08 | −0.62 | −1.12 to −0.13 | 0.01 |

| Weight, kg (difference in change) | −1.58 | −3.21 to +0.06 | 0.06 | −1.72 | −3.49 to +0.06 | 0.06 | −1.42 | −3.22 to +0.37 | 0.12 |

| Skinfolds,c mm (difference in change) | −3.0 | −9.3 to 3.2 | 0.34 | −2.4 | −8.3 to +3.4 | 0.42 | −5.7 | −11.6 to +0.1 | 0.05d |

| Incidence of obesitye (OR) | 0.03 | 0.00 to 0.32 | 0.003 | -f | -f | 0.002g | 0.07 | 0.01 to 0.68 | 0.02 |

| Incidence of excess weight gainh (OR) | 0.16 | 0.04 to 0.59 | 0.006 | 0.19 | 0.04 to 0.83 | 0.03 | 0.14 | 0.03 to 0.74 | 0.02 |

| Analysis of all subjects using multiple imputations | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obesity prevention interventions (combined) compared to control intervention | Beverages-only intervention compared to control intervention | Multiple-behaviors intervention compared to control intervention | |||||||

| Difference in change or odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | Difference in change or odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | Difference in change or odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence intervals | p-value | |

| BMIa z-score, SD (difference in change) | −0.089 | −0.170 to −0.008 | 0.03 | −0.077 | −0.170 to +0.017 | 0.11 | −0.083 | −0.165 to −0.001 | 0.05i |

| BMI,a kg/m2 (difference in change) | −0.48 | −1.04 to +0.08 | 0.10 | −0.39 | −1.00 to +0.23 | 0.22 | −0.45 | −1.02 to +0.12 | 0.12 |

| Weight, kg (difference in change) | −1.44 | −2.98 to +0.10 | 0.07 | −1.55 | −3.34 to +0.25 | 0.09 | −1.10 | −2.58 to +0.37 | 0.14 |

| Skinfolds,c mm (difference in change) | −2.3 | −8.5 to +3.9 | 0.47 | −1.2 | −7.9 to +5.4 | 0.71 | −1.8 | −8.6 to +5.0 | 0.60 |

| Incidence of obesitye(OR) | 0.10 | 0.01 to 0.65 | 0.02 | -f | -f | -f | 0.14 | 0.02 to 1.08 | 0.06 |

| Incidence of excess weight gainh(OR) | 0.27 | 0.08 to 0.87 | 0.03 | 0.27 | 0.07 to 1.09 | 0.07 | 0.25 | 0.06 to 1.05 | 0.07 |

BMI: Body mass index

Rounded to 0.05 from 0.045

Sum of triceps, biceps, sub-scapular, and supra-iliac skinfold thickness

Rounded to 0.05 from 0.054

BMI at or above the 95th percentile of a reference population 18

Unable to derive odds ratio: five out of 18 of subjects became obese in the control intervention (incidence of 28%) compared to 0 out of 40 subjects in the beverages-only intervention (incidence of 0%) among competers

p-value derived using Fisher exact test

Excess weight gain as defined by Steven, et al.:21 changes in BMI of more than 3% above expected changes with age

Rounded to 0.05 from 0.048

Figure 2.

Changes in BMI z-score from baseline to end of intervention (12 months). Error bars represent changes standard error of the mean.

In the secondary analyses, with post-hoc analyses at 12 months, subjects randomized to the beverages-only intervention did not have changes in anthropometric values that were different from the controls, but the incidence of obesity was decreased with 5 out of the 18 non-obese controls becoming obese (28%) compared to 0 out of the 40 non-obese subjects (0%) in the beverages-only intervention. An odds ratio could not be derived, but the Fisher exact test for completers allowed the derivation of a p value of 0.002. Excess weight gain was present in 3 out of 51 completers (6%) of the beverages-only intervention. Subjects in the multiple-behavior intervention had a smaller average change in BMIz than those in the control group in both the completers or the multiple imputations analyses (Table 3) and excess weight gain occurred in 2 out of 46 completers (4%) of the multiple-behavior intervention.

Using 12-month data as outcome, adjusted for baseline data, as suggested by Vickers,22 findings were essentially the same, with the notable exception of group differences in changes in skinfold thickness: combined vs. control −5.4 mm (95%CI: −10.6 to −0.2, p=0.04), beverage only vs. control −4.5 (−8.9 to −0.2, 0.04), multiple vs. control −8.8 (−13.0 to −4.5, <0.001) for the completers and −4.2 (−8.9 to +0.6, 0.08), −2.6 (−7.6 to +2.5, 0.32), −4.2 (−9.3 to +0.9, 0.11), respectively, for the multiple imputation. As this analysis was not specified a priori, these findings should be interpreted with caution.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first intervention focused on pediatric obesity prevention and delivered entirely by primary care staff to show a significant impact on weight status variables. These findings suggest that trained, supported, and compensated pediatric primary care staff can implement a theory-based behavioral intervention with sufficient efficacy to impact excess weight gain among children of motivated families.

Previous studies in the pediatric primary care setting have shown efficacy of treatment for children and adolescents who are already obese,24–28 but less success has been reported for prevention. Using post-hoc analyses, Taveras, et al. showed an impact of a primary-care obesity prevention intervention in younger children (ages 2–6 years) on BMI in girls only (−0.38 kg/m2, 95% confidence interval [CI]: −0.73 to −0.03), but this was not statistically significant in the primary analysis of the entire group of subjects (−0.21 kg/m2, 95%CI: −0.50 to +0.07).11 This study also differed from the present study in that the intervention was delivered in primary care, but by members of the research team, rather than staff of the practices. Other interventions in the pediatric primary care setting focused on obesity prevention have not shown a significant impact on the weight status variables.8–10,12–14 In the present study, we showed clinically significant, and, for the primary outcome, statistically significant intervention effects. Group differences in BMIz were about −0.09 SD, BMI about −0.50 kg/m2, and weight about −1.5 kg. These differences are of smaller magnitude than what was hypothesized for the sample size calculation (−0.28 SD at 24 months, or −0.14 SD at 12 months) and therefore their clinical significance may be questioned. The incidences of obesity and excess weight gain were consistently different between the combined obesity and the control intervention groups, but the small sample size limits interpretation. Among completers, excess weight gain was less frequent in either obesity interventions than in the control intervention group.

Several reasons could explain why our intervention was more successful than previously reported interventions. It was based on a behavioral theory successful in the research setting, had a relatively high intensity (12 sessions), and was conducted on a selected population of motivated families by clinical staff that already had a trusting relationship with families. Our findings suggest that primary care staff can implement such programs with an impact on weight changes, but it probably requires that they are compensated, trained, and supported by behavioral experts. Subjects also reported that the small gifts that they could exchange for the points they earned were an important motivation. While the cost of these small gifts was minimal, some type of external structure may be necessary to support interventions in primary care.

Secondary analyses performed post-hoc at 12 instead of 24 months and comparing the beverage-only or the multiple-behavior interventions to the control intervention are more difficult to interpret. Nevertheless, some trends are suggestive. The effect size appeared to be similar with both interventions (Figure 2), suggesting that, in the context of prevention, focusing on a single behavior may be just as successful, as has been shown by others.29 In the analysis of completers, that could not be verified in the analysis of all subjects, the incidence of obesity was significantly decreased in the group with the beverages-only intervention, supporting other findings suggestive of a causal link between sugar-sweetened beverages intake and the development of obesity.17,29

This study has several limitations. As the study was substantially underpowered to test the a priori hypotheses, negative results should be interpreted with caution, but this limitation does not affect the validity of the statistically significant findings. The study staff measuring the outcomes could not be blinded due to the randomization by practice due to the location of the measurement visits. “Smart Steps” was an efficacy study and thus, subjects more likely to be successful were selected by requesting the return of a food record. This resulted in only a small fraction of approached families being motivated enough to participate. As an efficacy study, no effort was made to increase recruitment of less motivated families or at understanding reason for participation using qualitative research. Therefore no recommendation can be made, based on the present study, to design an effectiveness study that would focus on these questions. While the low participation should not affect the validity of our findings, their generalizability to all children at risk of excess weight gain and to real-world primary care patient population is questionable. Therefore, clinicians may want to focus their efforts on families that have demonstrated their motivation until effectiveness studies are conducted. Loss to follow-up is also a concern. The difficulties in recruiting practices and clinicians suggest that the current United States pediatric primary care model may not yet be structured to accommodate the intensity of the effort necessary for effective obesity prevention. While this was not a statistically significant difference, a larger proportion of Blacks was included in the multiple behavior intervention, which could have biased the results. The study also had important strengths, including a control group with a similar number of encounters but unrelated to weight, a cluster randomization, a diverse population of subjects, and an intervention integrated into primary care practice.

This study demonstrates that obesity prevention by pediatric primary care providers can have an impact on BMIz but is challenging to implement. While this was not specifically tested, clinicians may have to be trained, continuously supported by a team of behavioral specialists, and compensated to implement the intervention. These findings may have important implications for public health and insurers. Further research should address effectiveness, costs, and benefits in order to define whether this approach should be used in clinical practice.

What is already known about this subject

Theory-based interventions are effective for obesity treatment or in the research setting.

Childhood obesity prevention has had some success in school and community settings.

Most prevention interventions in the primary-care setting, among children at risk for obesity, have not had a significant impact on weight gain.

What this study adds

For motivated families, an intensive theory- and family-based behavioral intervention implemented by pediatric primary care staff can prevent excess weight gain.

Obesity prevention interventions in the pediatric primary care setting may not necessarily need to be delivered by specialized staff.

Continuous financial and technical support (training and ongoing contacts with behavioral specialists) may however be necessary.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the network of primary care clinicians, their patients and families for their contribution to this project and clinical research facilitated through the Pediatric Research Consortium (PeRC) at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, as well as the following practices’ clinicians, patients, and families outside The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia network: Lower Bucks Pediatrics, St. Mary Children’s Health Center, Girard College, and Brighton Pediatrics.

NS, SKK, JS, AP, RIB, and MSF conceptualized and designed the study. NS, BHW, DLH, SKK, SSL, AP, RIB, and MSF designed the intervention. NS, BHW, DLH, SSL, AP, and MSF conducted the primary care staff training. NS, BHW, DLH, MSX, and SN collected the data. NS, BHW, DLH, MSX, SN, JS, and AP performed the data analysis and interpretation. NS drafted the initial manuscript. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

The study were funded by an National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant, 5R01HL084056

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- CHOP

The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

- CI

confidence interval

- GEE

generalized estimating equations

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest Statement

Dr. Stettler joined after the end of the study Exponent, Inc., a for-profit company that provides consulting services to several food and beverages companies. He also received travel support, but no compensation, from PepsiCo, Nestlé, and Danone while visiting these companies as part of a sabbatical. The remaining authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:483–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sobol-Goldberg S, Rabinowitz J, Gross R. School-based obesity prevention programs: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity. 2013;21:2422–8. doi: 10.1002/oby.20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elder JP, Crespo NC, Corder K, et al. Childhood obesity prevention and control in city recreation centres and family homes: the MOVE/me Muevo Project. Pediatric obesity. 2014;9:218–31. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleich SN, Segal J, Wu Y, Wilson R, Wang Y. Systematic Review of Community-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Studies. Pediatrics. 2013 doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swinburn B, Malakellis M, Moodie M, et al. Large reductions in child overweight and obesity in intervention and comparison communities 3 years after a community project. Pediatric obesity. 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster GD, Sundal D, Lent MR, McDermott C, Jelalian E, Vojta D. 18-month outcomes of a community-based treatment for childhood obesity. Pediatric obesity. 2014;9:e63–7. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Showell NN, Fawole O, Segal J, et al. A Systematic Review of Home-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Studies. Pediatrics. 2013 doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrick K, Calfas KJ, Norman GJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a primary care and home-based intervention for physical activity and nutrition behaviors: PACE+ for adolescents. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2006;160:128–36. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.2.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCallum Z, Wake M, Gerner B, et al. Outcome data from the LEAP (Live, Eat and Play) trial: a randomized controlled trial of a primary care intervention for childhood overweight/mild obesity. International journal of obesity. 2007;31:630–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwartz RP, Hamre R, Dietz WH, et al. Office-based motivational interviewing to prevent childhood obesity: a feasibility study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2007;161:495–501. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taveras EM, Gortmaker SL, Hohman KH, et al. Randomized controlled trial to improve primary care to prevent and manage childhood obesity: the High Five for Kids study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine. 2011;165:714–22. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Birken CS, Maguire J, Mekky M, et al. Office-based randomized controlled trial to reduce screen time in preschool children. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1110–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tucker SJ, Ytterberg KL, Lenoch LM, et al. Reducing pediatric overweight: nurse-delivered motivational interviewing in primary care. Journal of pediatric nursing. 2013;28:536–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Connor TM, Hilmers A, Watson K, Baranowski T, Giardino AP. Feasibility of an obesity intervention for paediatric primary care targeting parenting and children: Helping HAND. Child: care, health and development. 2013;39:141–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stettler N. The global epidemic of childhood obesity: is there a role for the paediatrician? Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2004;5:91–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barlow SE, Expert C. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120 (Suppl 4):S164–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebbeling CB, Feldman HA, Chomitz VR, et al. A randomized trial of sugar-sweetened beverages and adolescent body weight. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:1407–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, et al. CDC growth charts: United States. Advance Data. 2000:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.We Can! GO, SLOW, and WHOA Foods. at http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/obesity/wecan/downloads/go-slow-whoa.pdf.

- 20.Leff SS, Waasdorp TE, Paskewich B, et al. The Preventing Relational Aggression in Schools Everyday Program: A Preliminary Evaluation of Acceptability and Impact. School psychology review. 2010;39:569–87. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens J, Truesdale KP, Wang CH, Cai J. Prevention of excess gain. International journal of obesity. 2009;33:1207–10. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vickers AJ. The use of percentage change from baseline as an outcome in a controlled trial is statistically inefficient: a simulation study. BMC medical research methodology. 2001;1:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JH. Interpreting incomplete data in studies of diet and weight loss. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;348 doi: 10.1056/NEJMe030054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sargent GM, Pilotto LS, Baur LA. Components of primary care interventions to treat childhood overweight and obesity: a systematic review of effect. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2011;12:e219–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quattrin T, Roemmich JN, Paluch R, Yu J, Epstein LH, Ecker MA. Efficacy of family-based weight control program for preschool children in primary care. Pediatrics. 2012;130:660–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vine M, Hargreaves MB, Briefel RR, Orfield C. Expanding the role of primary care in the prevention and treatment of childhood obesity: a review of clinic- and community-based recommendations and interventions. Journal of obesity. 2013;2013:172035. doi: 10.1155/2013/172035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hollinghurst S, Hunt LP, Banks J, Sharp DJ, Shield JP. Cost and effectiveness of treatment options for childhood obesity. Pediatric obesity. 2014;9:e26–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2013.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marild S, Gronowitz E, Forsell C, Dahlgren J, Friberg P. A controlled study of lifestyle treatment in primary care for children with obesity. Pediatric obesity. 2013;8:207–17. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Ruyter JC, Olthof MR, Seidell JC, Katan MB. A trial of sugar-free or sugar-sweetened beverages and body weight in children. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367:1397–406. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]