Abstract

Introduction

The relation between serum rheumatoid factor levels and the extent, severity, and complexity of coronary artery disease has not been adequately studied.

Aim

Therefore, we assessed the relationship between the severity of coronary artery disease assessed by SYNTAX score and serum rheumatoid factor levels in patients with stable coronary artery disease.

Material and methods

We enrolled 268 consecutive patients who underwent coronary angiography. Patients with acute coronary syndrome and chronic immune disorders were excluded. Baseline serum rheumatoid factor levels were measured and the SYNTAX score was calculated from the study population.

Results

Patients were divided into two groups. Group 1 was defined as low SYNTAX score < 22, and group 2 was defined as intermediate and high SYNTAX score > 22. Serum rheumatoid factor levels were significantly higher in the intermediate and high-SYNTAX score group than in the low-SYNTAX score group (16.4 ±9 IU/mlvs. 11.36 ±5 IU/ml, p < 0.001). Also, there was a significant correlation between rheumatoid factor and CRP levels with the SYNTAX score r = 0.411; p < 0.001 and r = 0.275; p < 0.001, respectively. On multivariate linear regression analysis, rheumatoid factor (β = 0.101, p < 0.001) was an independent risk factor for intermediate and high SYNTAX score in patients with stable coronary artery disease. In receiver operator characteristic curve analysis, optimal cut-off value of rheumatoid factor to predict high SYNTAX score was found to be 10.5 IU/ml, with 69% sensitivity and 61% specificity.

Conclusions

The rheumatoid factor level was independently associated with the extent, complexity, and severity of coronary artery disease assessed by SYNTAX score in patients with stable coronary artery diseases.

Keywords: rheumatoid factor, SYNTAX score, inflammation, autoantibodies

Introduction

Inflammation plays a pivotal role in the progression of atherosclerosis. Autoimmunity has been thought to be a causative factor for atherosclerosis. In fact, it seems that both the cellular and humoral immune systems are involved in the development and progression of atherosclerosis [1]. The reports of autoantibodies and the chronic inflammatory response associated with them are far from conclusive. Autoantibodies, which have been implicated as being associated with atherosclerosis, include those against oxidized low-density lipoprotein, cardiolipin, β2-glycoprotein I, heat shock proteins 60/65, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and rheumatoid factor (RF). Previous studies [2, 3] were conducted to delineate an association between RF and atherogenesis. Recently, RF has been associated with an increased likelihood of developing coronary artery disease (CAD) and independently associated with cardiovascular mortality in healthy subjects [3].

The SYNTAX score (SX score) is based on a visual assessment of coronary lesions by coronary angiograms and is used to evaluate the severity of CAD. It is able to aid revascularisation decisions and predicts mortality and morbidity in patients with CAD [4].

Aim

In this present study, we evaluated the relationship between RF levels and coronary complexity, severity, and extent assessed by SX score in non-rheumatoid arthritis patients with stable coronary artery disease.

Material and methods

Study population

We enrolled 268 consecutive patients with stable angina pectoris who underwent coronary angiography for suspected CAD between January 2013 and June 2013. Patients with: acute coronary syndrome; SYNTAX score of zero; history of previous myocardial infarction (MI), coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were excluded. Similarly, patients with known haemodynamic instability, neoplastic disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic hepatic diseases, chronic or current infections, any systemic diseases, autoimmune diseases, or connective tissue diseases that could cause high RF concentrations were also excluded. Rheumatologic diseases were excluded by a rheumatology specialist. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at our centre. A clinical history of risk factors – such as age, sex, diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HT), hyperlipidaemia (HL), and smoking – was recorded. For each patient, height and weight were measured and the body mass index (BMI) was calculated. Fasting blood samples were collected 1 day before coronary angiography for the evaluation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglyceride (TG), and blood glucose levels. Serum RF levels were measured by the ELISA (Roche/Hitachi analyser, Mannheim, Germany), and the normal range of RF activity was recognised as 5–20 IU/ml. Positive results were defined by the manufacturer's instructions (RF > 20 IU/ml). C-reactive protein (CRP) was measured in serum by enzyme immunoassay (EIA) (Immage CRP EIA Kit; Beckman Coulter Inc, Brea, CA), and the normal range of CRP was recognized as 0–0.08 mg/dl. Hypertension was defined as having at least two blood pressure measurements > 140/90 mm Hg or using antihypertensive drugs, whereas DM was defined as having at least two fasting blood sugar measurements > 126 mg/dl or using antidiabetic drugs. Estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) was calculated by the Cockcroft-Gault formula ([140 – age] × [weight (kg)] × [0.85, if female]/[72 × creatinine]). Medications used prior to the coronary angiography were noted.

SYNTAX score

SYNTAX score is an angiographic tool used in grading the complexity of CAD. Each coronary lesion with a diameter stenosis ≥ 50% in vessels ≥ 1.5 mm was scored. The latest online updated version (2.03) was used in the calculation of the SYNTAX scores (www.syntaxscore.com) [5]. A low SX score was defined as ≤ 22, an intermediate score as 23 to 32, and a high score as ≥ 33 [6]. Our study population was grouped as SX score ≤ 22 (low SX score tertile) and SX score > 22 (intermediate and high SX score tertiles) to assess the association of RF with SX score. All angiographic variables of the SX score were computed by two experienced cardiologists who were blinded to the procedural data and clinical outcomes. In case of disagreement, the final decision was reached by consensus.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range) values, whereas categorical variables were presented as numbers. The differences between normally distributed numeric variables were evaluated by Student's t-test while non-normally distributed variables were analysed by Mann-Whitney U test, as appropriate. The χ2 test was employed for the comparison of categorical variables. Spearman correlation analysis was performed between variables. In order to determine the independent predictors of intermediate and high SX score group, parameters that were found to have significance (p ≤ 0.05) in the univariate analysis, were evaluated by stepwise forward multivariate linear regression analysis. 95% confidence interval and odds ratios (OR) were presented together. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to determine the predictive value of RF and CRP on intermediate and high SX score patients. In all statistical analyses, p < 0.05 was recognised as statistically significant. We conducted our statistical analyses with SPSS 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) package program.

Results

In total, 268 stable patients with CAD were included in the study. There were 172 patients (mean age: 57.8 ±10.5 years; 53% male) in the low SX score group and 96 patients (mean age: 61.7 ±11.4 years; 66% male) in the intermediate to high SX score group. Baseline clinical, angiographic and laboratory characteristics of the patients according SX score groups are shown in Table I. Cardiovascular therapy was not significantly different between two groups.

Table I.

Baseline characteristics

| Parameter | SYNTAX score ≤ 22 (n = 172) | SYNTAX score > 22 (n = 96) | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD [years] | 57.8 ±10.5 | 61.7 ±11.4 | 0.005 |

| Male, n (%) | 91 (53) | 63 (66) | 0.043 |

| BMI, mean ± SD [kg/m2] | 27.4 ±3.6 | 27.5 ±2.6 | 0.903 |

| Family history, n (%) | 102 (59) | 71 (74) | 0.016 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 77 (45) | 58 (60) | 0.014 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 95 (55.2) | 68 (71) | 0.060 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 33 (19) | 30 (31) | 0.026 |

| LDL-C, mean ± SD [mg/dl] | 110.8 ±30.1 | 122.9 ±35.2 | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C, mean ± SD [mg/dl] | 46.7 ±8.6 | 44.7 ±8.2 | 0.058 |

| TG, mean ± SD [mg/dl] | 144.8 ±41.2 | 152.1 ±55.1 | 0.220 |

| Fasting blood glucose, mean ± SD [mg/dl] | 110.7 ±25.3 | 121.8 ±23.4 | < 0.001 |

| CrCl, mean ± SD [ml/min] | 101.1 +30.8 | 92.7 ±31.9 | 0.035 |

| CRP, mean ± SD [mg/dl] | 0.84 ±1.2 | 1.69 ±2.2 | < 0.001 |

| RF, mean ± SD [IU/ml] | 11.36 ±5 | 16.4 ±9 | < 0.001 |

| RF positive (> 20 IU/ml), n (%) | 12 (7) | 38 (40) | < 0.001 |

| ACE-inh/ARB use, n (%) | 97 (56.4) | 63 (65.6) | 0.140 |

| Statin use, n (%) | 43 (25) | 30 (32.3) | 0.270 |

| β-Blocker use, n (%) | 104 (60) | 62 (64.6) | 0.506 |

| Ca+ + channel blocker use, n (%) | 28 (16.3) | 15 (15.6) | 0.889 |

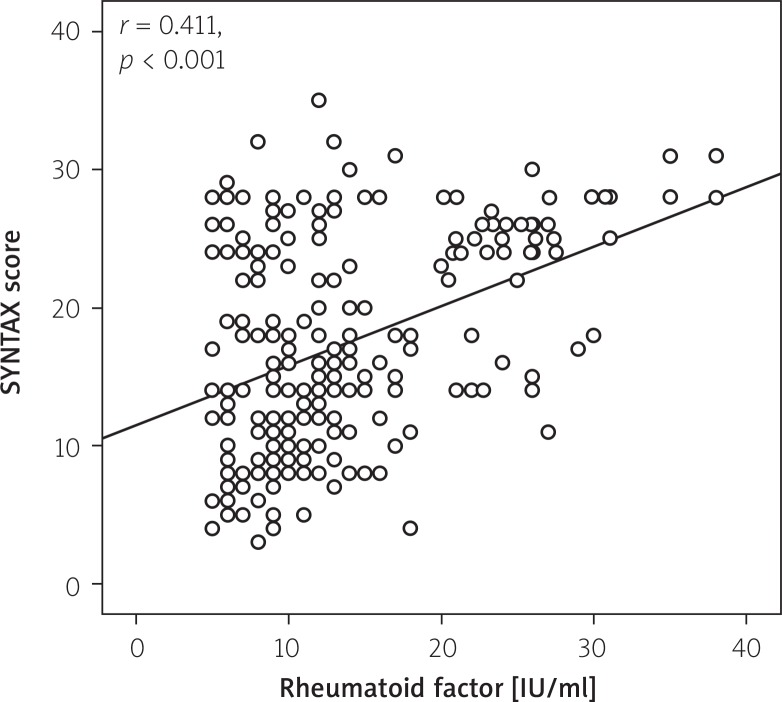

The RF levels were significantly higher in the intermediate to high SX score group than in the low SX score group (16.4 ±9 IU/ml vs. 11.36 ±5 IU/ml, p < 0.001). A positive RF was present in 12 (7%) in the low SX score group and 38 (40%) in the intermediate to high SX score group. Also, there was a significant correlation between RF and CRP levels with the SX score (r = 0.411; p < 0.001; (Figure 1) and r = 0.275; p < 0.001, respectively). Moreover, RF and CRP levels were found to be well correlated with each other (r = 0.353; p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Correlation plot from rheumatoid factor levels and SX score

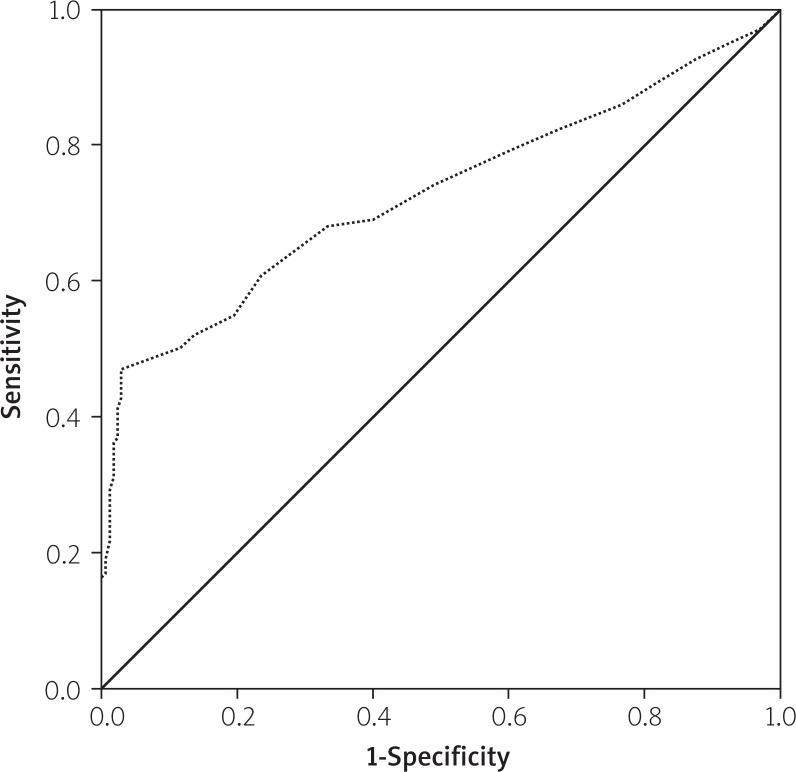

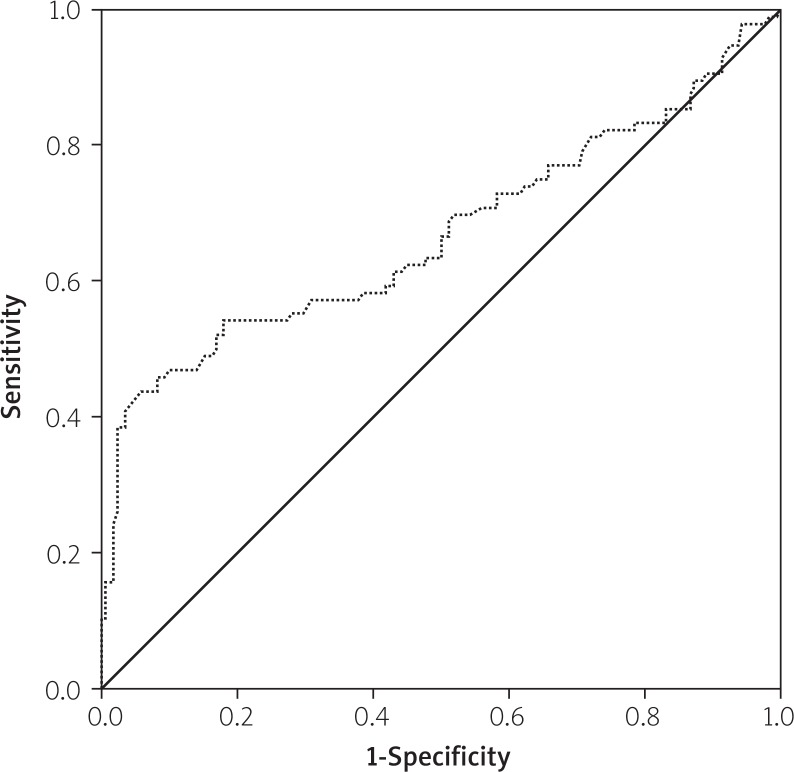

The effects of multiple variables on the intermediate to high SX score were analysed with univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses. The parameters which had shown significance in the univariate analysis (age, male sex, RF, LDL, CrCl, DM, HT, family history of CAD, CRP, fasting blood glucose, and smoking) were evaluated by multivariate linear regression analysis in order to determine the independent predictors of intermediate to high SX score. Thus, serum RF, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, LDL-cholesterol, CRP, and smoking were found to be independent predictors of intermediate to high SX score (Table II). The ROC analysis yielded a cut-off value of 10.5 IU/ml for RF to predict intermediate to high SX score with 69% sensitivity and 61% specificity, with the area under the ROC curve being 0.727 (95% CI: 0.658–0.795, p < 0.001) (Figure 2). The ROC analysis yielded a cut off value of 0.432 mg/dl for CRP to predict high SX score with 67% sensitivity and 56% specificity, with the area under the ROC curve being 0.669 (95% CI: 0.595–0.744, p < 0.001) (Figure 3).

Table II.

Multivariate linear regression analysis

| Parameter | Unstandardised coefficients βa | Standardised coefficients βa | Value of t | Value of p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF [IU/ml] | 0.297 | 0.283 | 4.998 | < 0.001 |

| CRP [mg/dl] | 1.990 | 0.276 | 5.255 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes | 3.834 | 0.216 | 4.123 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 2.852 | 0.185 | 3.737 | < 0.001 |

| Fasting blood glucose [mg/dl] | 0.046 | 0.154 | 2.904 | 0.004 |

| Smoking | 2.024 | 0.134 | 2.747 | 0.006 |

Dependent variable: SYNTAX score.

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves of rheumatoid factor for the identification of patients with intermediate to high SX score

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic curves of CRP for the identification of patients with intermediate to high SX score

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between total RF levels and the severity of disease in patients with stable CAD. A higher baseline RF value was independently associated with the severity and coronary complexity of CAD, as assessed by SX score.

There are various scales for the assessment of the extent and severity of CAD. However, SX score does not only enable the assessment of CAD extent and severity, but also differs from the other methods by allowing us to evaluate the coronary lesion complexity [4]. In addition, the reproducibility of the SX score has proven the feasibility of the method in clinical use [7, 8]. We determined a relationship between the SX score and RF levels, and also found a significant positive correlation between the SX score and RF levels. Moreover, serum RF values were observed to be an independent predictor of intermediate to high SX score group.

The autoantibody RF is found in 80% of patients with RA and may also be seen in low titres in patients with chronic infections, other autoimmune diseases, and chronic pulmonary, hepatic, or renal diseases. However, RF is present in as many as 15% of normal adults [9]. Therefore, a lot of studies [2, 3] have been conducted to delineate an association between RF and atherogenesis. The interest in RF and atherosclerosis also arose from the strong existing relationship between rheumatoid arthritis and accelerated cardiac and cerebral atherogenic processes [10, 11]. A role of RF per se as a pathogen was suggested by Edwards et al.[3], who reported its probable involvement in the development of ischaemic heart disease in the general population, particularly men. Whereas Qadan et al. observed no correlation between peripheral atherosclerosis and RF levels [12]. Although, there are few studies that have assessed the association between the atherosclerosis and RF [2, 3], the association between the level of RF and the extent, complexity, and severity of CAD has not been established. In this study, we determined a relationship between the RF and the extent, complexity, and severity of CAD assessed by SYNTAX score in stable coronary artery disease in non-rheumatoid arthritis patients. Also, we found a significant positive correlation between the SX score and the RF levels. Tomasson et al. suggested that in a general population cohort, RF was associated with increased all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors, even in subjects without joint symptoms [13]. In our study, we did not investigate the relation between RF and long-term mortality. In univariate analysis, there were significant differences between groups with SX score > 22 and SX score ≤ 22, with respect to RF, DM, HT, BMI, smoking, CrCl, LDL, CRP, age, male sex, family history, and fasting glucose levels. However, after multivariate linear regression analysis, serum RF levels were identified as an independent risk factor that correlates with the severity of CAD. Another study also supports our conclusion [3].

We proposed some possible mechanistic explanations for the relationship between RF and complexity of CAD. Chronic inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and subsequent cardiovascular disease [14–16], and increased concentrations of mediators or markers of inflammation predict subsequent atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the general population [17]. Recently, CRP has become an inflammatory marker and independent risk factor for atherosclerosis [18, 19]. It is known that elevation of CRP is associated with the extent and severity of CAD [20]. In our present study we also found positive correlation between high CRP levels and intermediate to high SX score. Moreover, we found that elevated CRP levels, which are a direct indicator of inflammation, were also associated with elevated RF levels. The links between CRP and autoantibodies such as RF in the atherosclerosis process have been demonstrated in several studies [21–23]. The association of autoimmunity and RF with atherosclerosis provides further evidence of the importance of inflammation and raises the possibility that autoimmune mechanisms may play a part. Our study cannot determine whether RF in the subjects examined is a nonspecific marker of inflammation or is involved directly in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. However, it is also possible that, in RF positive subjects, immunological factors play a role that is independent of inflammation; circulating immune complexes have been associated with incident MI and it is possible that RF has a direct pathological effect on the endothelium [24–26]. There is circumstantial evidence for this: atherosclerotic plaques contain immunoglobulins and complement suggesting immune complex activity [27]. In addition, Edwards et al. suggested that RF may play an important role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis independent of non-specific polyclonal B-cell activation secondary to inflammation. There is also an intriguing possibility that the pathological process involved in ischaemic heart disease, such as atheroma formation, may generate inflammatory tissue capable of producing RF [3]. In view of these findings, we believe that increased inflammatory activity and an elevated RF value are related to the extent, severity, and complexity of CAD.

The present investigation has several limitations. It is a single-centre experience and includes a small number of patients. It would be better to include more patients to increase the statistical power. Our selected population was free of other confounders of systemic inflammation, and we did not have data about inflammatory markers other than CRP, such as interleukin 6, tumour necrosis factor alpha, etc., which may be accepted as a limitation. In this study, only RF was measured. Other antibodies which might also be relevant to atherosclerosis, such as those against ANA, cardiolipin, and vascular components, should be considered in further studies regarding the interaction of CRP, autoimmunity, and atherosclerosis. Further data are also needed to explore the mechanisms underlying the RF, atherosclerosis, and CAD. This was a cross-sectional study. Another limitation of the current study is that because there was no long-term follow-up of the patients, we could not provide any prognostic data in terms of future cardiovascular events. Furthermore, the relation between RF and other plaque burden measurements such as number of lesioned vessels or Gensini Score was not studied in the present study.

Conclusions

The RF level was independently associated with the extent, complexity, and severity of CAD assessed by SYNTAX score in patients with stable coronary artery diseases. Also, we found a significant positive correlation between the SX score and the RF levels. In addition, serum RF levels may be useful markers of the severity of CAD. The association of RF levels with the extent, complexity, and severity of CAD provides further evidence of the importance of inflammation and raises the possibility that autoimmune mechanisms may play a role. Large prospective studies are further required to establish the immune-pathological mechanism of RF in atherosclerotic processes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Sherer Y, Shoenfeld Y. Atherosclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:97–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grainger DJ, Bethell HW. High titers of serum antinuclear antibodies, mostly directed against nucleolar antigens, are associated with the presence of coronary atherosclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:110–4. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards CJ, Syddall H, Goswami R, et al. Hertfordshire Cohort Study Group The autoantibody rheumatoid factor may be an independent risk factor for ischemic heart disease in men. Heart. 2007;93:1263–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.097816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sianos G, Morel MA, Kappetein AP, et al. The SYNTAX Score: an angiographic tool grading the complexity of coronary artery disease. EuroIntervention. 2005;1:219–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.SYNTAX working group. SYNTAX score calculator. Available at http://www.syntaxscore.com. Accessed May 20, 2012.

- 6.Serruys PW, Morice MC, Kappetein AP, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus coronary-artery bypass grafting for severe coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:961–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanboga IH, Ekinci M, Isik T, et al. Reproducibility of syntax score: from core lab to real world. J Interv Cardiol. 2011;24:302–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.2011.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aksakal E, Tanboga IH, Kurt M, et al. The relation of serum gammaglutamyl transferase levels with coronary lesion complexity and longterm outcomein patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2012;221:596–601. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkelsen WM, Dodge HJ, Duff IF, Kato H. Estimates of the prevalence of rheumatic diseases in the population of Tecumseh, Michigan, 1959-60. J Chronic Dis. 1967;20:351–69. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(67)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolfe F, Freundlich B, Straus WL. Increasein cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease prevalence in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2003;30:36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shoenfeld Y, Gerli R, Doria A, et al. Accelerated atherosclerosis in autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Circulation. 2005;112:3337–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.507996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qadan LR, Ahmed AA, Abdel-Jalil S, Al-Bader MA. Significance of antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor in patients with advanced peripheral arterial disease. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:192–5. doi: 10.1159/000273071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomasson G, Aspelund T, Jonsson T, et al. Effect of rheumatoid factor on mortality and coronary heart disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1649–54. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.110536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ross R. Atherosclerosise – an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;14:115e26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedicino D, Giglio AF, Galiffa VA, et al. Infections, immunity and atherosclerosis: pathogenic mechanisms and unsolved questions. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166:572–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.05.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labarrere CA, Zaloga GP. C-reactive protein: from innocent bystander to pivotal mediator of atherosclerosis. Am J Med. 2004;117:499–507. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun H, Koike T, Ichikawa T, et al. Creactive protein in atherosclerotic lesions: its origin and pathological significance. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1139–48. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61202-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniguchi H, Momiyama Y, Ohmori R, et al. Associations of plasma C-reactive protein levels with the presence and extent of coronary stenosis in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 2005;178:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Szalai AJ. C-reactive protein (CRP) and autoimmunedisease: facts and conjectures. Clin Dev Immunol. 2004;11:221–6. doi: 10.1080/17402520400001751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du Clos TW, Mold C. C-reactive protein: anactivator of innate immunity and a modulatorof adaptive immunity. Immunol Res. 2004;30:261–77. doi: 10.1385/IR:30:3:261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ogden CA, Elkon KB. Single-dose therapy for lupus nephritis: C-reactive protein, nature's own dual scavenger and immunosuppressant. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:378–81. doi: 10.1002/art.20847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mustafa A, Nityanand S, Berglund L, et al. Circulating immune complexes in 50-year old men as a strong and independent risk factor for myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;102:2576–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.21.2576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kato H, Yamakawa M, Ogino T. Complement mediated vascular endothelial injury in rheumatoid nodules: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1839–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tighe H, Carson DA. Rheumatoid factor. In: Ruddy S, Harris ED, Sledge CB, editors. Kelley's textbook of rheumatology. 6th ed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 2001. pp. 151–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wick G, Knoflach M, Xu Q. Autoimmune and inflammatory mechanisms in atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:361–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.012703.104644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]