ABSTRACT

Coenzyme A (CoA) is a ubiquitous coenzyme involved in fundamental metabolic processes. CoA is synthesized from pantothenic acid by a pathway that is largely conserved among bacteria and eukaryotes and consists of five enzymatic steps. While higher organisms, including humans, must scavenge pantothenate from the environment, most bacteria and plants are capable of de novo pantothenate biosynthesis. In Salmonella enterica, precursors to pantothenate can be salvaged, but subsequent intermediates are not transported due to their phosphorylated state, and thus the pathway from pantothenate to CoA is considered essential. Genetic analyses identified the STM4195 gene product of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium as a transporter of pantothenate precursors, ketopantoate and pantoate and, to a lesser extent, pantothenate. Further results indicated that STM4195 transports a product of CoA degradation that serves as a precursor to CoA and enters the biosynthetic pathway between PanC and CoaBC (dfp). The relevant CoA derivative is distinguishable from pantothenate, pantetheine, and pantethine and has spectral properties indicating the adenine moiety of CoA is intact. Taken together, the results presented here provide evidence of a transport mechanism for the uptake of ketopantoate, pantoate, and pantothenate and demonstrate a role for STM4195 in the salvage of a CoA derivative of unknown structure. The STM4195 gene is renamed panS to reflect participation in pantothenate salvage that was uncovered herein.

IMPORTANCE This manuscript describes a transporter for two pantothenate precursors in addition to the existence and transport of a salvageable coenzyme A (CoA) derivative. Specifically, these studies defined a function for an STM protein in S. enterica that was distinct from the annotated role and led to its designation as PanS (pantothenate salvage). The presence of a salvageable CoA derivative and a transporter for it suggests the possibility that this compound is present in the environment and may serve a role in CoA synthesis for some organisms. As such, this work raises important question about CoA salvage that can be pursued with future studies in bacteria and other organisms.

INTRODUCTION

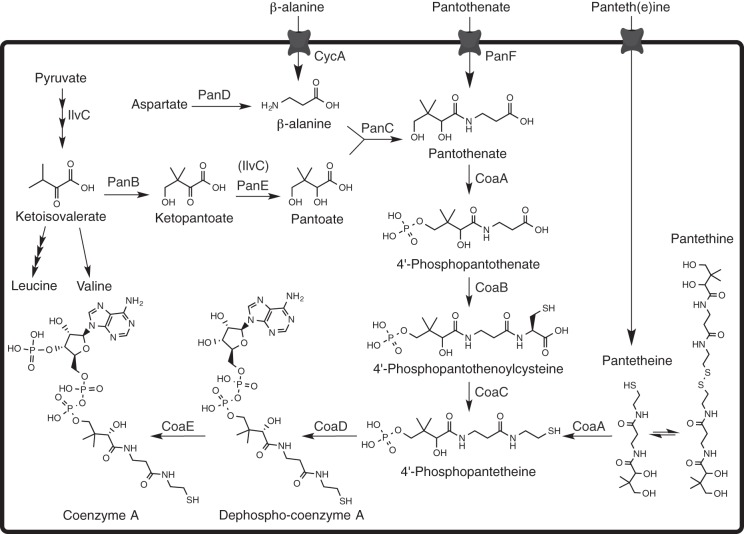

Coenzyme A (CoA) is essential for reactions of central metabolism, where it facilitates the activation of carbonyl groups and acts in the biosynthesis and degradation of fatty acids, polyketides, and nonribosomal peptides (1). Nine percent of known enzymatic activities are dependent on CoA or a thioester derivative (2). In eukaryotes and bacteria, CoA biosynthesis stems from the vitamin pantothenic acid (B5), and many higher organisms rely on dietary pantothenate to satisfy their CoA requirement (1). In contrast, many plants, fungi and microorganisms such as Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica possess the enzymes necessary for de novo biosynthesis of pantothenate from β-alanine and α-ketoisovalerate (Fig. 1) (1, 3). Briefly, aspartate α-decarboxylase (PanD; EC 4.1.1.11) catalyzes the production of β-alanine from l-aspartate. The activity of ketopantoate hydroxymethyltransferase (PanB; EC 2.1.2.11) converts the branch-point metabolite α-ketoisovalerate to ketopantoate, which is subsequently reduced to pantoate by ketopantoate reductase (PanE; EC 1.1.1.169). Acetohydroxyacid isomoreductase (IlvC; EC 1.1.1.86) catalyzes the same reduction of ketopantoate to pantoate, although much less efficiently than PanE, making the activities of PanE and IlvC partially redundant in the cell (4). Finally, pantothenate is produced by the ATP-dependent ligation of pantoate and β-alanine, catalyzed by pantothenate synthase (PanC; EC 6.3.2.1).

FIG 1.

Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis in Salmonella enterica. Known biosynthetic enzymes, salvage enzymes, and metabolic intermediates involved in CoA biosynthesis and salvage are depicted.

Many organisms actively transport pantothenate into the cell (1). E. coli and S. enterica have a sodium-dependent pantothenate permease (PanF) with high affinity for the substrate pantothenate (Kt = 0.4 μM in E. coli) (5). Exogenous ketopantoate, pantoate, and β-alanine stimulated pantothenate production in E. coli under various growth conditions, which suggested these intermediates were also salvaged by the cell (6). However, of these three, only the transport of β-alanine by CycA has been characterized (7).

In most bacteria, plants, and mammals the formation of CoA from pantothenate requires five enzymatic steps (Fig. 1). The first committed step in CoA biosynthesis is the ATP-dependent phosphorylation of pantothenate to form 4′-phosphopanothenate catalyzed by pantothenate kinase (CoaA; EC 2.7.1.33) (6). Most organisms cannot salvage exogenous CoA or its phosphorylated intermediates, making the pathway beyond pantothenate essential for viability (2). An exception is pantetheine, which is transported by an unknown mechanism, and phosphorylated by pantothenate kinase (CoaA) to generate 4′-phosphopantetheine, the substrate for phosphopantetheine adenyltransferase (CoaD; EC 2.7.7.3) (2). Thus, exogenous pantetheine can bypass the need for the steps catalyzed by CoaBC (EC 4.1.1.36, 6.3.2.5) but requires CoaA (Fig. 1). The mechanism of pantetheine uptake in E. coli and S. enterica is PanF independent, but otherwise uncharacterized (8). After adenylation, dephospho-CoA is phosphorylated by dephospho-CoA kinase (CoaE; 2.7.1.24). CoA and its thioester derivatives allosterically inhibit pantothenate kinase, thus coordinating CoA biosynthesis with the metabolic state of the cell (9). As a result of this allosteric regulation, E. coli is capable of accumulating a 15-fold excess of pantothenate relative to CoA (6), a strategy that ensures rapid generation of CoA when a need arises.

Essential metabolic pathways can be used to gain insights about metabolic robustness and probe how the cell responds to perturbations in the metabolic network (10). If the primary ketopantoate reductase in S. enterica, PanE, is disrupted, the cellular CoA levels are decreased ∼10-fold (11). However, in this strain the redundant ketopantoate reductase activity of IlvC produced sufficient CoA to support prototrophic growth (4). The low level of CoA present in a panE mutant caused multiple phenotypes that were used to detect metabolic integration of biochemical pathways (11). In the present study, a panE ilvC mutant strain that lacked all ketopantoate reductase activity was used to isolate suppressors in an effort to uncover alternative routes of CoA biosynthesis supported by robustness in the metabolic network. These studies uncovered a role for the previously uncharacterized open reading frame, panS (previously STM4195), in CoA salvage and detected a novel CoA derivative that could be incorporated into the biosynthetic pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, media, and chemicals.

All strains used in the present study are derivatives of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2 and are listed with their genotype in Table 1. Tn10d(Tc) refers to the transposition defective mini-Tn10 (Tn10Δ16 Δ17) described by Way et al. (12), while Tn10 refers to the full-length transposable element (13). MudJ refers to the Mud1734 transposon described previously (14), and Tn10d-Cam refers to the transposition defective Tn10 specifying chloramphenicol resistance (15).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains

| Straina | Genotypeb |

|---|---|

| LT2 | Wild type |

| DM3547 | panC617::Tn10d(Tc) |

| DM6486 | panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10 |

| DM13708 | panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10 STM4195p1 |

| DM13710 | panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10 STM4195p3 |

| DM13950 | panC617::Tn10d(Tc)/pDM1397 |

| DM13951 | panC617::Tn10d(Tc)/pEmpty |

| DM13947 | panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10/pDM1397 |

| DM13948 | panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10/pEmpty |

| DM14101 | panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10 zxx10185::Tn10d-Cam STM4195p1 |

| DM14206 | ΔpanE802 ΔilvC3218 STM4195-2::Kn/pDM1397 |

| DM14207 | ΔpanE802 ΔilvC3218 STM4195-2::Kn/pEmpty |

| DM14273 | panB611::Tn10d(Tc) STM4195-2::Kn/pDM1397 |

| DM14274 | panB611::Tn10d(Tc) STM4195-2::Kn/pEmpty |

| DM14459 | dfp2::Kn/pDM1397 |

| DM14460 | dfp2::Kn/pEmpty |

| DM14525 | zxx8038::Tn10d(Tc) coaA1 STM4195-2::Kn/pDM1397 |

| DM14526 | zxx8038::Tn10d(Tc) coaA1 STM4195-2::Kn/pEmpty |

| DM14575 | ΔpanE802 ΔilvC3218 STM4195-2::Kn panF803::Cam |

| DM14576 | ΔpanE802 ΔilvC3218 STM4195-2::Kn panF803::Cam/pEmpty |

| DM14577 | ΔpanE802 ΔilvC3218 STM4195-2::Kn panF803::Cam/pDM1397 |

No-carbon E medium (NCE) supplemented with 1 mM MgSO4 (16), trace minerals (17), and glucose (11 mM) as the sole carbon source was used as minimal medium. Difco nutrient broth (8 g/liter) with NaCl (5 g/liter) and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth were used as rich media. Difco BiTek agar (15 g/liter) was added for solid medium. When necessary the branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) leucine, isoleucine, and valine (plus ketoisovalerate) were added at a final concentration of 0.3 mM. Antibiotics were added as needed to reach the following concentrations in rich and minimal medium, respectively: tetracycline at 20 and 10 μg/ml, ampicillin at 30 and 15 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol at 20 and 5 μg/ml. Coenzyme A sodium salt hydrate, d-pantothenic acid, and d-pantethine were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Pantetheine was made by adding dithiothreitol (20 mM final) to a stock of 20 mM pantethine and incubating at room temperature overnight. Ketopantoate and pantoate were synthesized from their respective lactonized forms using the method of Primerano and Burns (4).

Genetic methods.

All transductional crosses were performed using the high-frequency general transducing mutant of bacteriophage P22 (HT105/1, int-201) (18). Methods for performing transductional crosses, purification of transductants from phage, and the identification of phage-free recombinants have been described previously (19, 20). All mutant strains were constructed using standard genetic techniques. The panE and ilvC loci were replaced with chloramphenicol and kanamycin drug resistance cassettes, respectively, using the λ-Red recombinase system described by Datsenko and Wanner (21). Insertions in STM4195, panF, and dfp were generated using similar methods. When necessary, drug cassettes were resolved using the Flp-FRT recombination method previously described (21). The nomenclature used here associated with STM4195 follows classical genetic format; the gene locus is denoted STM4195, the gene product is referred to as STM4195 and genetic lesions affecting expression isolated are referred to here by allele names STM4195p1-11 to reflect their impact on the promoter.

Mutant isolation.

Eleven cultures of DM6486 (panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10) were grown overnight in LB medium. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in an equal volume of saline solution (85 mM). Approximately 108 cells from each cell suspension were spread onto solid glucose medium containing 1% Difco vitamin-assay Casamino Acids (CAA). Plated cultures were incubated at 37°C for a period of 24 to 48 h. The resulting mutant colonies were streaked out on nonselective medium. Phenotypes were confirmed by patching mutant isolates to nonselective rich medium, which were then replica printed to selective plates after a period of 6 to 12 h at 37°C. A representative mutant strain displaying CAA-dependent growth, DM13708 (panE675::MudJ ilvC2104::Tn10 STM4195p1), was used to generate a pool of ∼60,000 cells with random Tn10d-Cam insertions throughout the chromosome. A P22 lysate grown on this pool and standard genetic approaches identified Tn10d-Cam insertions linked to the causative suppressor mutation. The site of insertion was determined by sequence analyses using degenerate primers and those specific to the Tn10d-Cam (22). DNA sequence was obtained at the University of Wisconsin Biotechnology Center.

Phenotypic analysis.

Nutritional requirements were determined on solid media and in liquid growth media as described below.

(i) Liquid growth.

Strains to be analyzed were grown in LB broth overnight. Cultures were pelleted and resuspended in an equal volume of glucose minimal medium supplemented with BCAA. Cultures were then returned to 37°C for a period of 2 to 3 h in order to deplete metabolite pools until growth of the appropriate strains abated. After metabolite depletion, 2 μl of the cell suspension was added to 198 μl of the desired medium contained in each well of a 96-well microtiter plate. Cultures were grown at 37°C while shaking using the Biotek EL808 Ultra microplate reader. Cell density was measured as the absorbance at 650 nm. The specific growth rate was determined as [μ = ln(X/X0)/T], wherein X is the optical density during the linear growth phase and T is time.

(ii) Solid media.

Nutritional requirements were determined using soft agar overlays containing cells of the relevant strain. Compounds were spotted on the overlay and growth was scored after 24 to 48 h at 37°C.

Quantification of CoA pool size.

Overnight cultures of the strains to be analyzed were grown in LB broth. Cultures were pelleted and resuspended in saline solution. Culture flasks containing 200 ml of glucose minimal medium supplemented with 0.2% CAA were inoculated to a starting optical density at 650 nm (OD650) of 0.02. Growth was carried out at 37°C while shaking until a final OD650 of 0.6 was achieved. Cells were pelleted and stored at −80°C until ready for analysis. CoA levels were determined by the method of Allred and Guy (23).

Molecular methods.

The STM4195 gene was amplified by PCR with Herculase II Fusion DNA polymerase (Agilent) using primers stm4195_NcoI_F (5′-GAGACCATGGCCATGCTCGCCG TCATTACC-3′) and stm4195_XbaI_R (5′-GAGATCTAGATTAATTTACCTTTGCCGTTT-3′). The resulting PCR product was gel purified, digested with NcoI (Promega) and XbaI (Promega), and ligated into NcoI/XbaI-cut pBAD24 (24). Constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α and screened for vectors containing inserts. Plasmid inserts were confirmed by sequencing. Plasmids containing the appropriate insert (designated pDM1397) were purified and transformed into the relevant strains.

Bioinformatics analyses.

The S. enterica LT2 genome sequence (25) was used to analyze the chromosomal region immediately 5′ of the STM4195 translation start site. Promoter predictions were made using BPROM (Soft Berry). Protein sequence alignments were performed using Clustal Omega (EBI) and formatted using BoxShade (SIB).

Formation and characterization of a transported, biologically active CoA derivative.

Coenzyme A (Sigma) was dissolved in water to a final concentration of 100 mM. Aliquots were heated at 98°C for 0 to 5 h using an Eppendorf MasterCycler nexus. Individual samples from each time point were pooled and filtered using a 0.22-μm centrifuge tube filter (Costar) prior to testing for biological activity as described in the text. Dephospo-CoA was formed by incubating a 100 mM stock of CoA (100 μl) with 2 Units of rAPid alkaline phosphatase (Roche) at 37°C for 2 h. The resulting sample was resolved by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Biologically active samples were analyzed via HPLC using an anion-exchange column (250 by 4.6 mm) packed with Partisil-10 SAX resin (Phenomenex). The column was equipped with an NH2 SecurityGuard cartridge (Phenomenex). The analysis method was adapted from Jackowski and Rock (27). A linear gradient of monobasic potassium phosphate running from 0.05 to 0.9 M was introduced to the column over the course of 30 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. β-Mercaptoethanol was included in the mobile phase at a final concentration of 1 mM. Mobile-phase delivery was carried out using the Shimadzu Prominence LC-20AT pump system, and the peak absorbance from 200 to 400 nm was monitored by using a Shimadzu SPD-M20A diode array detector. Elution fractions were collected using the FRC-10A fraction collector (Shimadzu). When necessary, fractions were concentrated by evaporation using the Eppendorf Vacufuge. Concentrated samples with biological activity were further resolved and salts were removed by injection onto a Gemini C18 reverse-phase column (Phenomenex). Hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP; Sigma), used as an ion pairing reagent, was dissolved in water to a final concentration of 800 mM and adjusted to a final pH of 7 with triethylamine. The HFIP solution was divided and mixed 1:1 with either water or 100% methanol, forming mobile phases A and B, respectively. The flow rate was adjusted to 0.5 ml/min, and samples were eluted during a 10-min isocratic step of 95% mobile phase A and 5% mobile phase B, followed by a 20-min gradient to 100% mobile phase B. Isolated fractions were again concentrated and tested for biological activity. Samples with biological activity had maximal absorbance at 259 nm. Biologically active fractions were then dried, resuspended in 50% methanol-water, and submitted for mass spectrometry analysis at the University of Georgia Proteomic and Mass Spectrometry core facility.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A panE ilvC strain requires branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) and pantothenate for growth on glucose minimal medium (Fig. 2). Mutations that allowed strain DM6486 (panE ilvC) to grow in the absence of exogenous pantothenate, potentially by altering metabolic flux, were sought on minimal medium supplemented with BCAA. The desired mutants were not found, despite looking for both spontaneous and diethyl sulfate induced mutations. It was considered formally possible that mutations that restored pantoate synthesis would be deleterious to the function of another pathway and thus generate a new growth requirement. To account for this possibility, the growth medium was supplemented with vitamin-free Casamino Acids (CAA). The parental strain showed the expected requirement for pantothenate or pantoate on this medium, which confirmed that pantothenate was not present in the CAA solution to levels sufficient to allow growth.

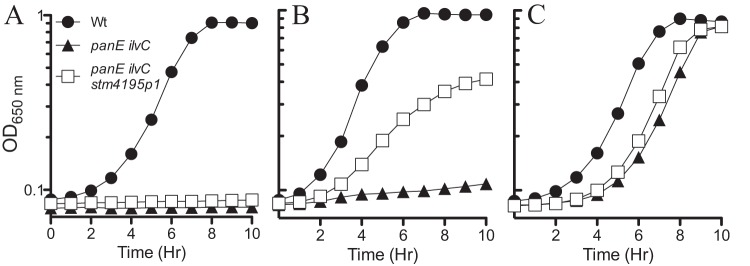

FIG 2.

The STM4195p1 allele restores growth to a panE ilvC strain. Cultures were grown in glucose minimal medium containing BCAA with no additional supplements (A), vitamin-free CAA (0.2%) (B), or pantothenate (100 μM) (C). Wild-type LT2 (Wt), panE ilvC (DM6486), and panE ilvC STM4195p1 (DM13708) strains are shown in each panel. The data displayed are representative of three independent cultures.

Eleven independent, spontaneously arising, derivatives of DM6486 (panE ilvC) were isolated on glucose minimal medium supplemented with 1% CAA. Growth of the 11 isolates was quantified in liquid medium and each grew when pantothenate or CAA was added to the medium. The data in Fig. 2 show the growth of a representative revertant strain, DM13708. Growth of each of the revertant strains was less than wild-type, both in rate and final density, and proportional to the concentration of CAA added (data not shown). Growth of these strains was not supported by the simultaneous addition all 20 common amino acids, suggesting a minor component of the CAA was responsible for growth of the revertant strains. Although the revertant strains had detectable total CoA levels, concentrations were <50% of the amount found in a panE strain, indicating that CoA synthesis was only partially restored (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

The STM4195p1 allele allows a low level of CoA synthesis

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Avg CoA level ± SDa (nmol/mg [dry wt]) | Ratio of CoA levels (wt/mutant) | Avg growth rate ± SDb (h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LT2 | Wild type | 0.464 ± 0.051 | 0.508 ± 0.005 | |

| DM6486 | panE ilvC | NGc | NG | |

| DM12653 | panE | 0.034 ± 0.005 | 13.5 | 0.498 ± 0.004 |

| DM13708 | panE ilvC STM4195p1 | 0.013 ± 0.006 | 35.4 | 0.255 ± 0.002 |

CoA levels were determined from cultures grown at 37°C in culture flasks containing minimal medium with glucose (11 mM) as the sole carbon source and supplemented with vitamin-free Casamino Acids (0.2% [wt/vol]). The data are displayed as the averages for three independent cultures.

Growth curves were performed in a 96-well plate. Minimal growth medium contained glucose (11 mM) supplemented with Casamino Acids (0.2% [wt/vol]). The specific growth rate was determined as μ = ln(X/X0)/T. The data are displayed as averages for three independent cultures.

NG, no growth (the strain was unable to grow under the conditions tested).

Transposition events lead to pantothenate-independent growth of the panE ilvC strain.

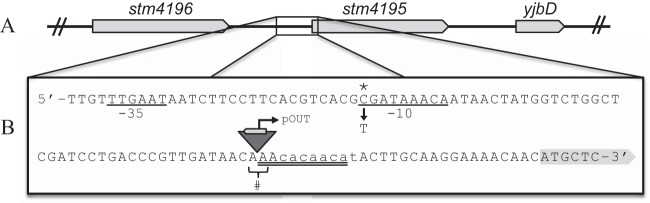

Standard genetic techniques identified a modified transposon (zxx10185::Tn10d-Cam) that was linked by transduction to the causative lesion in all 11 strains. Sequence analysis identified the causative lesions in each revertant strain in a region on the chromosome depicted in Fig. 3A. Ten of the eleven strains contained an insertion of IS10-right (IS10-R), the active element in transposon Tn10, 28 bp upstream of the predicted translation start site of STM4195 (STM4195p1; Fig. 3B). The reading frame of the transposase gene encoded by IS10-R was oriented in the opposite direction relative to STM4195 and shared 100% identity with the E. coli IS10-R, encoding a functional transposase flanked by inverted repeats (28, 29). The IS10-R is presumed to have originated from the nondefective Tn10 insertion present in ilvC of the parent strain (DM6486). The frequency with which this class of suppressor mutations was isolated suggested that the sequence upstream of STM4195 contained a hot spot for DNA insertion (30). Sequence analysis of the chromosome–IS10-R junction sites revealed a 9-bp duplication of chromosomal DNA flanking the IS10-R element (Fig. 3B). The 9-bp sequence showed symmetry similar to previously characterized insertion hot spots (31, 32). Previous studies have demonstrated that the presence of a functional transposase in the genome can increase the activation of “silent” genes 5- to 25-fold (33). IS10-R possesses a strong promoter that reads out of the transposase coding region (pOUT) and potentiates the activation of adjacent genes (Fig. 3B) (34).

FIG 3.

Mutations in the chromosome upstream of STM4195 restored growth to a panE ilvC strain when grown in the presence of CAA. (A) The open reading frame organization in the relevant genomic region is depicted. (B) The sequence upstream of the STM4195 coding region has been expanded. The predicted −10/−35 promoter regions are underlined. Lowercase letters depict the regulatory binding site for the small RNA repressor, GcvB (41). Allele STM4195p1 contains an IS10-R insertion, indicated by the inverted triangle, inserted 24 bp upstream of the STM4195 start codon (#). The coding sequence of the transposase gene encoded by IS10-R is indicated, as is the promoter reading out of the IS10-R coding region (pOUT). The double-underlined region indicates the 9-bp insertion site recognition sequence that is found duplicated at both ends of the IS10-R insertion (31). The position of allele STM4195p3 (C to T) is denoted with an asterisk and is in the predicted −10 region, 76 bp upstream of the STM4195 start codon.

The remaining mutation was a single C-to-T transition 76 bp upstream of the STM4195 translation start site (STM4195p3; Fig. 3B). The promoter prediction tool BPROM (SoftBerry) indicated the base substitution was in the −10 region of the promoter of STM4195. The substitution resulted in a sigma 70 recognition site closer to the −10 consensus sequence (35). Based on the sequence data, the saturation of the mutant hunt and the precedent in the literature (33, 36), we hypothesized that increased expression of STM4195 was the mechanism of suppression.

Increased expression of STM4195 allows growth of pantothenate auxotrophs with CAA.

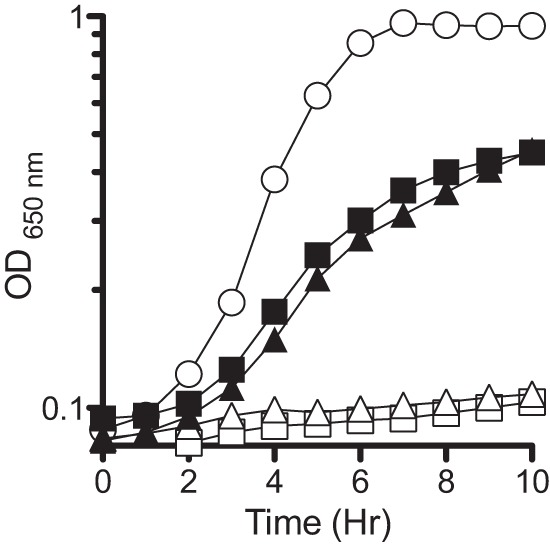

A construct encoding STM4195 transcribed by the arabinose-inducible pBAD promoter (pDM1397) was introduced into strain DM6486 (panE ilvC). Growth of the resulting strain (DM13947) in the absence of pantothenate, but the presence of CAA (0.2%), was restored only when STM4195 expression was induced (Fig. 4). These data confirmed that increased expression of STM4195 mimicked the effect of the mutations described above. Further, expression of STM4195 from pDM1397 restored growth to a panC strain (DM13950) in the presence of CAA (Fig. 4). These data allowed the conclusion that expression of STM4195 in the presence of CAA overcame the need for pantothenate synthesis.

FIG 4.

Expression of STM4195 in trans suppresses growth defect in the presence of CAA. panE ilvC (squares) strains containing pDM1397 (DM13947; filled) or the vector only control (DM13948; empty) and panC (triangles) strains containing pDM1397 (DM13950; filled) or vector only control (DM13951; empty) were grown in minimal medium containing CAA (0.2% [wt/vol]) and arabinose (1%). Growth was compared relative to that of the wild type (circles). The data displayed are representative of three independent cultures.

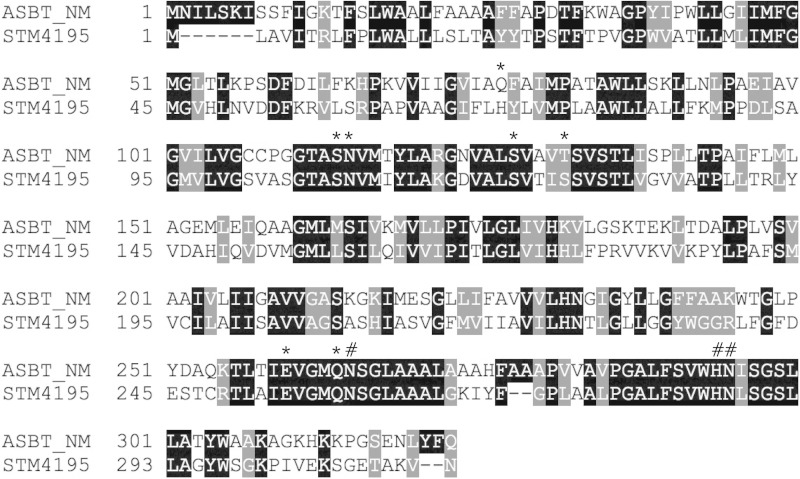

STM4195 is annotated as a Na+-dependent transporter (25). Protein domain analysis of STM4195 identified a single conserved domain (COG0385) belonging to the sodium bile acid symporter superfamily (SBF; cl19217), which includes transmembrane proteins involved in bile acid transport and resistance to arsenic compounds (37). The STM4195 homolog from Neisseria meningitidis (ASBTNM), which is 41% identical and 59% similar to the protein in S. enterica, has been characterized biochemically as a sodium-dependent bile acid symporter (38). Protein alignments showed that several residues essential for interacting with Na+ ions and a bile acid substrate in ASBTNM were conserved in STM4195 (Fig. 5) (38). The transmembrane prediction tool, TMHMM (Center for Biological Sequence Analysis), predicted that STM4195 consists of nine transmembrane helices. Taken together, the data were consistent with an impurity in the CAA being transported by STM4195 to restore growth to a pantothenate auxotroph.

FIG 5.

Alignment of STM4195 from Salmonella enterica and a homolog from Neisseria meningitidis (ASBTNM; NMB0705). Asterisks indicate residues from ASBTNM that coordinate sodium with their side chains (38). Hash symbols indicate residues from ASBTNM important for binding taurocholate (38). Identical residues and similar residues are highlighted black and gray, respectively.

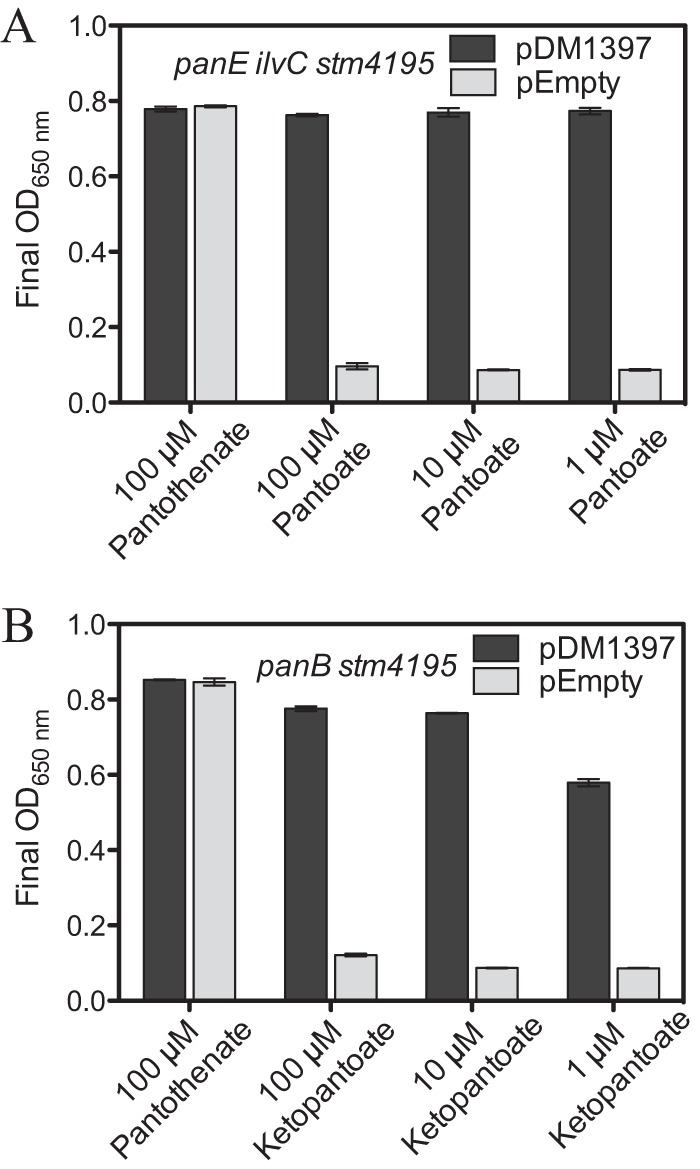

Commercially available intermediates of the CoA biosynthetic pathway were used to explore the substrate specificity of the predicted transporter. Pantoate and ketopantoate were provided in a range of concentrations to panE ilvC and panB strains, respectively, that carried an inducible STM4195 construct (pDM1397) or the vector-only control (pEmpty). The chromosomal STM4195 gene was inactivated (STM4195::Kn) to clarify interpretation of the results. Relevant data are presented in Fig. 6. A panE ilvC STM4195 strain grew on glucose minimal medium in the presence of 0.1 to 100 μM pantoate only when STM4195 was expressed in trans (Fig. 6A). The panE ilvC STM4195 strains containing either pDM1397 or pEmpty had the same growth characteristics in the presence of pantothenate (100 μM). Concentrations of pantoate equal to or exceeding 1 mM resulted in growth of a panE ilvC STM4195 strain containing the empty vector control, while concentrations of pantoate below 0.1 μM did not allow growth of a panE ilvC STM4195 strain despite STM4195 expression in trans (data not shown). Ketopantoate (1 to 100 μM) provided to a panB STM4195 strain rescued growth only when STM4195 was expressed in trans (Fig. 6B). Exogenous ketopantoate at ≥1 mM rescued growth independent of STM4195 expression (data not shown). The minimal concentration of pantothenate required for growth of a pantothenate auxotroph (DM14206) was not altered by STM4195 expression. Disruption of the panF gene in a panE ilvC STM4195 background (DM14575) prevented growth in the presence of exogenous pantothenate (100 μM; data not shown). However, the introduction of pDM1397 (DM14577) completely restored growth in the presence of 100 μM pantothenate and allowed limited growth with 10 μM pantothenate. In contrast, the strain carrying the empty vector control (DM14576) failed to grow in either case (data not shown). Together, these data indicated that STM4195 functioned in the transport of pantoate, ketopantoate, and pantothenate. Notably, 10 μM pantothenate failed to support growth in DM14577 to the level allowed by 10 μM pantoate or ketopantoate in DM14206 or DM14273, respectively. These results indicated that STM4195 had a higher affinity for pantoate and ketopantoate than pantothenate. The ability of high concentrations (≥1 mM) of pantoate or ketopantoate to suppress the need for STM4195 production in a panE ilvC STM4195 or panB STM4195 background, respectively, indicated that at least one alternative, less-sensitive mechanism of pantoate and ketopantoate uptake exists in S. enterica. Exogenous pantetheine (reduced) or pantethine (oxidized) rescued growth of a panE ilvC strain completely lacking STM4195, indicating STM4195 was not required for the transport of these metabolites (data not shown).

FIG 6.

Expression of STM4195 facilitates ketopantoate and pantoate uptake. (A) Supplements were added at the indicated concentrations to panE ilvC STM4195 strains containing pDM1397 (DM14206) or the empty vector control (DM14207) grown in glucose minimal medium containing BCAA and 1% arabinose. (B) panB STM4195 strains carrying pDM1397 (DM14273) or the empty vector control (DM14274) were examined as described for panel A. The data from three independent cultures are represented as the average and standard deviation of the OD650 at 12 h (all cultures reached stationary phase at ∼12 h).

The experiments with known intermediates of pantothenate biosynthesis above failed to recapitulate the phenotype seen with CAA as the source of CoA. Specifically, the relevant metabolite in CAA supported growth of a panC strain only when STM4195 was expressed in trans despite the status of panF. Since STM4195 had protein features in common with bile acid symporters, the impact of bile salts on STM4195-dependent growth of a pantothenate auxotroph was tested. The addition of bile salts (0 to 0.5% [wt/vol]) to the growth medium failed to rescue growth of a panE ilvC STM4195 mutant expressing STM4195 in trans, indicating that a component of bile salts was not used in CoA biosynthesis (data not shown). The presence of bile salts in the growth medium (0 to 0.5% [wt/vol]) did not significantly alter growth of DM14206 when supplied CAA (data not shown), suggesting STM4195 had a higher affinity for the relevant metabolite in CAA than bile salts.

A derivative of CoA is transported by STM4195.

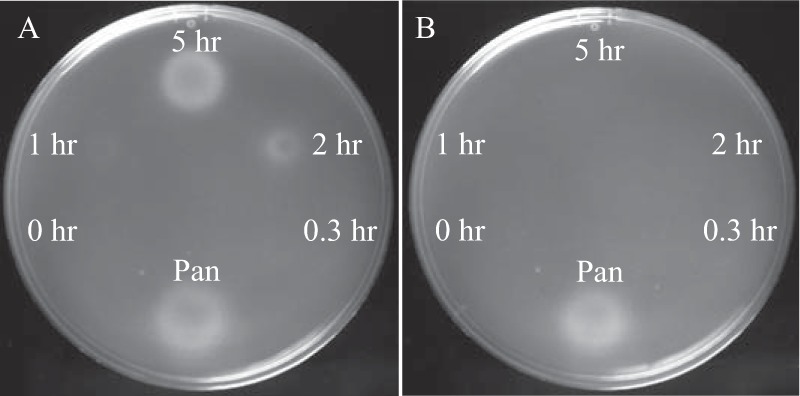

Although considered unlikely, it was formally possible that STM4195 was facilitating the transport of CoA itself. When crystals of pure CoA were spotted on a soft agar overlay containing DM13708 (panE ilvC STM4195p1), a small but noticeable zone of growth was visible after 18 h of incubation at 37°C. The concentration of CoA required to see a growth response was inconsistent with the technical analysis of the vitamin-assay grade CAA composition and suggested the growth was due to a breakdown product or contaminating precursor of CoA. A 100 mM solution of CoA was heated at 98°C and aliquots were taken over time and spotted on arabinose-containing soft agar overlays of DM14206 (panE ilvC STM4195 pDM1397) and DM14207 (panE ilvC STM4195 pEmpty). The data in Fig. 7 showed that the factor promoting STM4195-dependent growth of DM14206 increased over time and had little to no effect on growth of the empty vector control. Similar results were obtained with panC strains with or without expression of STM4195. These data supported the hypothesis that heating CoA accelerated its breakdown or transformation, thus enriching for a substrate of STM4195 that feeds into the CoA biosynthetic pathway downstream of pantothenate. Incubation of CoA with acid, base, alkaline phosphatase, or dithiothreitol failed to generate a factor active in growth assays. HPLC analysis of alkaline phosphatase-treated CoA revealed chromatogram peaks not observed in the untreated CoA sample that were consistent with the formation of dephospho-CoA, suggesting dephospho-CoA was not a substrate for STM4195. Interestingly, heating acetyl-CoA (100 mM) failed to generate a biologically active compound that stimulated growth of DM14206 (data not shown). These data suggested either the acetyl moiety of acetyl-CoA prevented the requisite breakdown/transformation or the acetyl group altered the structure of the resulting compound such that it was not recognized for transport by STM4195.

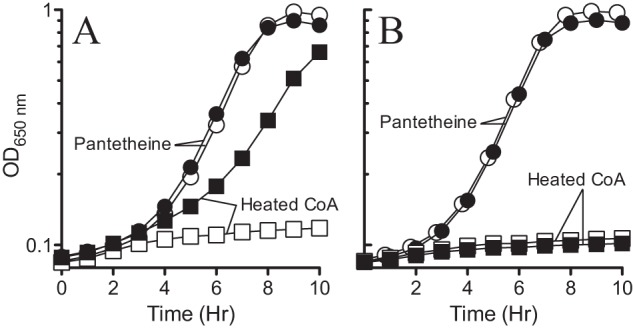

FIG 7.

Heated CoA produces substrates of STM4195. A 100 mM solution of CoA dissolved in water was heated at 98°C, and 5-μl aliquots were taken at the indicated time points and spotted on soft-agar overlays of panE ilvC STM4195 pDM1397 (DM14206) (A) and panE ilvC STM4195 pEmpty (DM14207) (B) strains grown on glucose minimal medium containing BCAA and 1% arabinose. Five microliters of pantothenate (Pan; 100 μM) was added as a positive control. Pictures were taken after 48 h of growth at 37°C.

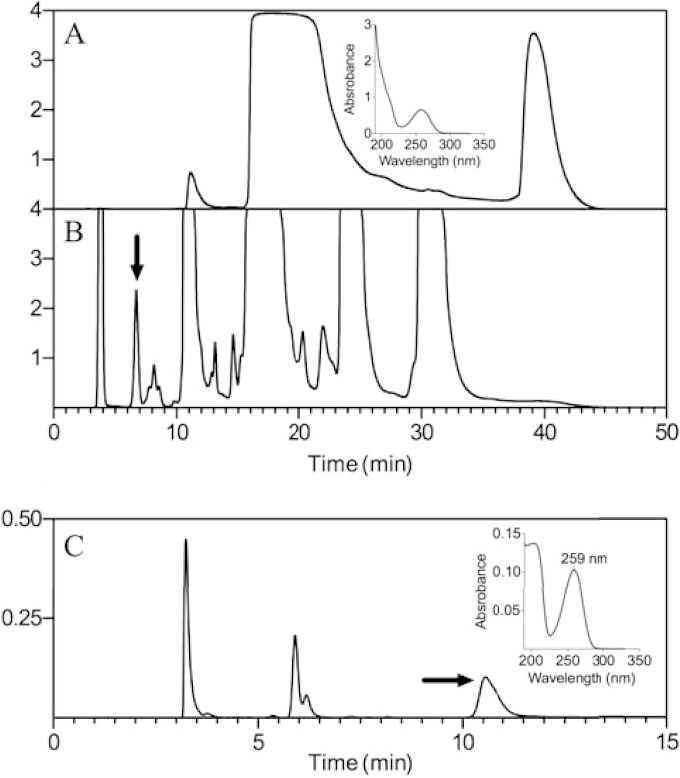

The biologically active compound derived from heating CoA was enriched by HPLC passage over an anion exchange column. During HPLC fractionation, absorbance was monitored from 200 to 400 nm, and fractions were collected over a 30-min mobile-phase gradient. Representative chromatographs of untreated CoA and heat-treated CoA displaying the absorbance at 259 nm are shown in Fig. 8A and B, respectively. Eluted fractions were assessed for biological activity by spotting 5 μl of filtered aliquots on agar overlays of DM14206 in the presence of arabinose. Only the fractions collected at time points between 5 and 7 min displayed biological activity. The sample collected from 5 to 7 min was further subjected to reversed-phase HPLC and revealed three peaks with maximal absorbance at 259 nm (Fig. 8C). Of these peaks, the fraction with a retention time of 10.5 min had biological activity. Tandem MS (MS/MS) analyses in both the positive- and the negative-ion mode failed to definitively identify the active compound, and a genetic approach was taken to pursue the physiological role of the relevant compound.

FIG 8.

HPLC separation of CoA breakdown products. (A) A 100-μl portion of 100 mM untreated CoA was separated by using an anion-exchange column while monitoring the absorbance at 259 nm. The inset displays the absorption spectrum of pure CoA (eluted at ∼15 min). (B) A 100-μl portion of 100 mM heat-treated CoA (98°C for 5 h) was separated using an anion-exchange column while monitoring the absorbance at 259 nm. Peak fractions were collected and tested for biological activity. The arrow indicates the only peak that displayed biological activity in STM4195-dependent growth assays. (C) The biologically active fraction collected in panel B was further resolved by reversed-phase chromatography while monitoring the absorbance at 259 nm. The arrow indicates the peak that displayed STM4195-dependent biological activity. The inset displays the absorption spectrum of the relevant peak from panel C, with a maximal absorbance at 259 nm.

S. enterica strains lacking dfp (coaBC) are viable if provided with exogenous pantetheine. Once inside the cell, pantetheine can be phosphorylated to enter the CoA biosynthetic pathway (Fig. 1). Growth data (Fig. 9) showed that the STM4195-dependent growth allowed by heated CoA required dfp. The expression of STM4195 supported growth of a panC strain supplied with heated CoA (1.25 mM; Fig. 9A), whereas STM4195 expression failed to support growth of the dfp strain grown under the same conditions (Fig. 9B). These results supported the conclusion that a biologically active compound was transported by STM4195 and entered the CoA pathway between PanC and CoaBC. Pantothenate kinase (encoded by coaA) is an essential enzyme and represents the only enzymatic step between PanC and CoaBC. The temperature-sensitive allele, coaA1(Ts) (11), was used to probe the role of this enzyme in salvaging the CoA breakdown compound. Strains carrying the coaA1 allele grow at 30°C but not at 42°C (11). Heat-treated CoA (∼1.5 mM) failed to support growth of DM14525 (coaA1 STM4195 pDM1397) at 42°C (data not shown). However, as an essential gene, there is no positive control for growth at 42°C, which prevented solid conclusions from these data (Fig. 1). In total, the data here supported the conclusion that STM4195 catalyzed the transport of a CoA-derived product that enters the CoA biosynthetic pathway after PanC, but upstream of CoaBC.

FIG 9.

STM4195-dependent growth requires CoaBC (dfp). STM4195-dependent growth of panC and dfp strains was tested on glucose minimal medium containing BCAA, 1% arabinose, and 1.25 mM heated CoA or 100 μM pantetheine. (A) Growth of panC strains carrying pDM1397 (DM13950; filled symbols) or pEmpty (DM13951; open symbols). (B) Growth of dfp strains carrying pDM1397 (DM14459; filled symbols) or pEmpty (DM14460; open symbols). The growth data are representative of three independent cultures.

Conclusions.

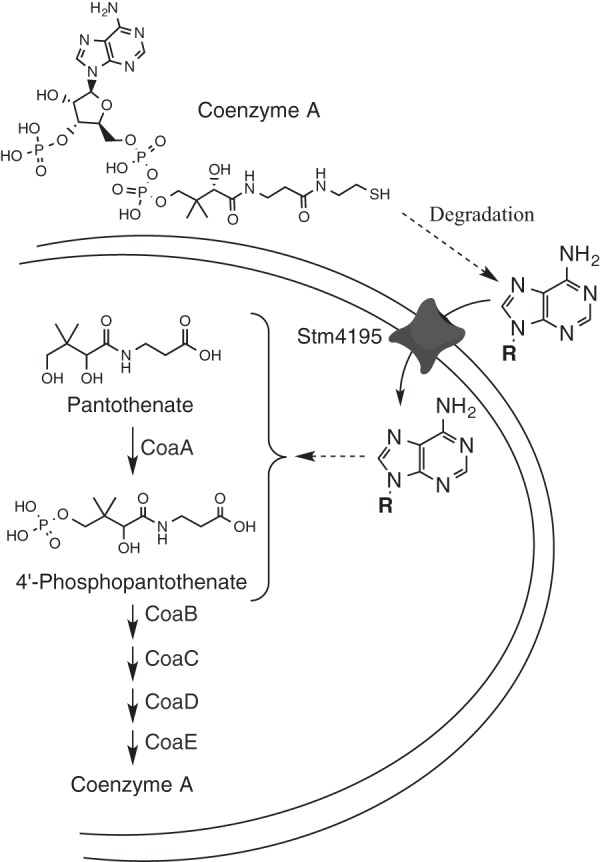

The STM4195 protein from Salmonella enterica is annotated as a Na+-dependent transporter with a single conserved domain (COG0385) that places it in the sodium bile acid symporter superfamily (SBF). The physiological work described here showed that STM4195 is unlikely to transport bile salts and rather transports precursors to CoA. Genetic analyses showed that STM4195 transports pantoate and ketopantoate with high affinity, pantothenate with low affinity, and a CoA-derived product of unknown structure. Figure 10 summarizes what is known about the CoA derivative and the STM4195 protein from the present study. The demonstration that a CoA derivative can be salvaged to satisfy the cellular requirement for this coenzyme suggests this compound (or related compounds) may exist in the environment and STM4195 is present to scavenge it. Further study is required to determine whether CoA salvage is the primary function of STM4195 or rather a consequence of enzymatic promiscuity. Nonetheless, it seems appropriate to rename STM4195 as PanS (pantothenate salvage) given the demonstrated impact of this protein on pantothenate and CoA metabolism in Salmonella.

FIG 10.

Model of STM4195-mediated salvage of a CoA derived product(s). STM4195 facilitates the uptake of a substrate derived from CoA that has spectral properties indicative of an intact adenine moiety. Spontaneous or enzymatic cleavage is required to release a compound that feeds into the pathway upstream of CoaBC.

Sodium bile acid superfamily (SBF) proteins are found across domains of life, and the work here augments our understanding of this family and provides an activity that is likely to be important in organisms besides S. enterica. Additional members of the SBF superfamily include the solute carrier family 10 (SLC10) transporters found in eukaryotes. Approximately 320 distinct human transporters belong to 1 of 43 SLC families (39). SLC10 comprises the sodium bile acid cotransporter family; however, not all members of the SLC10 family are involved in bile acid transport (39). STM4195 is >20% identical to SLC10A1 and SLC10A2 from Homo sapiens. Until now, the study of SBF family proteins, including SLC10 family members, has focused largely on the contribution these transporters make to the metabolism of bile acids and structurally related steroidal compounds, including cholesterol. Several SBF family proteins have been viewed as promising drug targets for cholesterol-lowering treatment (40). Our work highlights the need to consider alternative solutes that may serve as the substrates for these transporters in various contexts.

The STM4195 mRNA transcript has been described as a direct target of negative regulation by the Hfq-dependent small RNA, GcvB (41). The GcvB regulon consists largely of amino acid transporters, and to our knowledge, STM4195 represents the first vitamin-salvaging transporter to be identified in this regulon. As part of the GcvB regulon, STM4195 production is coordinated with the nutrient state of the cell, ensuring STM4195 production is greatest when nutrients are scarce.

Further study to address the in situ relevance of STM4195, and homologs found in other potentially pathogenic bacteria, is warranted based on interest in developing antimicrobial drugs that specifically target CoA biosynthesis in these organisms (42). If organisms posses a salvage mechanism which bypasses several steps of the de novo CoA pathway, accounting for the bypassed steps may pinpoint enzyme targets that are optimal for drug development. In contrast to the artificial production of CoA-derived products described here, it is possible that organisms growing in complex microbial communities are exposed to related CoA-degradation products as a result of bacterial cell lysis, host environment, and/or the activity of extracellular phosphatases/hydrolases acting on CoA directly to yield substrates for STM4195 and related transporters. The complete range of substrates recognized by STM4195 remains to be determined. Studies such as the one herein provide evidence that addressing metabolic robustness with in vivo tools can lead to new knowledge of mechanisms used in metabolic integration. This work provides fertile ground for continued efforts to understand mechanisms of metabolic integration that could influence drug targeting, synthetic biology, antibiotic development, and more.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by USPHS grant R01 GM047296 from the National Institutes of Health to D.M.D.

Mass spectrometry was done by the University of Georgia Proteomic and Mass Spectrometry core facility.

REFERENCES

- 1.Leonardi R, Zhang YM, Rock CO, Jackowski S. 2005. Coenzyme A: back in action. Prog Lipid Res 44:125–153. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spry C, Kirk K, Saliba KJ. 2008. Coenzyme A biosynthesis: an antimicrobial drug target. FEMS Microbiol Rev 32:56–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2007.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Webb ME, Smith AG, Abell C. 2004. Biosynthesis of pantothenate. Nat Prod Rep 21:695–721. doi: 10.1039/b316419p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Primerano DA, Burns RO. 1983. Role of acetohydroxy acid isomeroreductase in biosynthesis of pantothenic acid in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 153:259–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallari DS, Rock CO. 1985. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli pantothenate permease (panF) mutants. J Bacteriol 164:136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackowski S, Rock CO. 1981. Regulation of coenzyme A biosynthesis. J Bacteriol 148:926–932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider F, Krämer R, Burkovski A. 2004. Identification and characterization of the main β-alanine uptake system in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 65:576–582. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balibar CJ, Hollis-Symynkywicz MF, Tao J. 2011. Pantethine rescues phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase and phosphopantothenoylcysteine decarboxylase deficiency in Escherichia coli but not in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol 193:3304–3312. doi: 10.1128/JB.00334-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vallari D, Jackowski S, Rock C. 1987. Regulation of pantothenate kinase by coenzyme A and its thioesters. J Biol Chem 262:2468–2471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenigsknecht MJ, Downs DM. 2010. Thiamine biosynthesis can be used to dissect metabolic integration. Trends Microbiol 18:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frodyma M, Rubio A, Downs DM. 2000. Reduced flux through the purine biosynthetic pathway results in an increased requirement for coenzyme A in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 182:236–240. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.1.236-240.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Way JC, Davis MA, Morisato D, Roberts DE, Kleckner N. 1984. New Tn10 derivatives for transposon mutagenesis and for construction of lacZ operon fusions by transposition. Gene 32:369–379. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90012-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleckner N, Chan RK, Tye B-K, Botstein D. 1975. Mutagenesis by insertion of a drug-resistance element carrying an inverted repetition. J Mol Biol 97:561–575. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(75)80059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Castilho BA, Olfson P, Casadaban MJ. 1984. Plasmid insertion mutagenesis and lac gene fusion with mini-mu bacteriophage transposons. J Bacteriol 158:488–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliot T, Roth JR. 1988. Characterization of Tn10d-Cam: a transposition-defective Tn10 specifying chloramphenicol resistance. Mol Gen Genet MGG 213:332–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00339599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vogel HJ, Bonner DM. 1956. Acetylornithinase of Escherichia coli: partial purification and some properties. J Biol Chem 218:97–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balch WE, Wolfe RS. 1976. New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl Environ Microbiol 32:781–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmieger H. 1972. Phage P22-mutants with increased or decreased transduction abilities. Mol Gen Genet 119:75–88. doi: 10.1007/BF00270447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan RK, Botstein D, Watanabe T, Ogata Y. 1972. Specialized transduction of tetracycline resistance by phage P22 in Salmonella typhimurium. II. Properties of a high-frequency-transducing lysate. Virology 50:883–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Downs DM, Petersen L. 1994. apbA, a new genetic locus involved in thiamine biosynthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol 176:4858–4864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun S, Berg OG, Roth JR, Andersson DI. 2009. Contribution of gene amplification to evolution of increased antibiotic resistance in Salmonella typhimurium. Genetics 182:1183–1195. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.103028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allred JB, Guy DG. 1969. Determination of coenzyme A and acetyl CoA in tissue extract. Anal Biochem 29:293–299. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(69)90312-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose pBAD promoter. J Bacteriol 177:4121–4130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClelland M, Sanderson KE, Spieth J, Clifton SW, Latreille P, Courtney L, Porwollik S, Ali J, Dante M, Du F, Hou S, Layman D, Leonard S, Nguyen C, Scott K, Holmes A, Grewal N, Mulvaney E, Ryan E, Sun H, Florea L, Miller W, Stoneking T, Nhan M, Waterston R, Wilson RK. 2001. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium LT2. Nature 413:852–856. doi: 10.1038/35101614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reference deleted.

- 27.Jackowski S, Rock CO. 1984. Metabolism of 4′-phosphopantetheine in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 158:115–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster TJ, Davis MA, Roberts DE, Takeshita K, Kleckner N. 1981. Genetic organization of transposon Tn10. Cell 23:201–213. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90285-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Halling SM, Simons RW, Way JC, Walsh RB, Kleckner N. 1982. DNA sequence organization of IS10-right of Tn10 and comparison with IS10-left. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 79:2608–2612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.8.2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ross DG, Swan J, Kleckner N. 1979. Nearly precise excision: a new type of DNA alteration associated with the translocatable element Tn10. Cell 16:733–738. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Halling SM, Kleckner N. 1982. A symmetrical six-base-pair target site sequence determines Tn10 insertion specificity. Cell 28:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee SY, Butler D, Kleckner N. 1987. Efficient Tn10 transposition into a DNA insertion hot spot in vivo requires the 5-methyl groups of symmetrically disposed thymines within the hot-spot consensus sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84:7876–7880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.22.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang A, Roth JR. 1988. Activation of silent genes by transposons Tn5 and Tn10. Genetics 120:875–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simons RW, Hoopes BC, McClure WR, Kleckner N. 1983. Three promoters near the termini of ISI0: pIN, pOUT, and pIll. Cell 34:673–682. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90400-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hook-Barnard I, Johnson XB, Hinton DM. 2006. Escherichia coli RNA polymerase recognition of a σ70-Dependent promoter requiring a −35 DNA element and an extended −10 TGn motif. J Bacteriol 188:8352–8359. doi: 10.1128/JB.00853-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graña D, Youderian P, Susskind MM. 1985. Mutations that improve the ant promoter of Salmonella phage P22. Genetics 110:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marchler-Bauer A, Zheng C, Chitsaz F, Derbyshire MK, Geer LY, Geer RC, Gonzales NR, Gwadz M, Hurwitz DI, Lanczycki CJ, Lu F, Lu S, Marchler GH, Song JS, Thanki N, Yamashita RA, Zhang D, Bryant SH. 2013. CDD: conserved domains and protein three-dimensional structure. Nucleic Acids Res 41:D348–D352. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu N-J, Iwata S, Cameron AD, Drew D. 2011. Crystal structure of a bacterial homologue of the bile acid sodium symporter ASBT. Nature 478:408–411. doi: 10.1038/nature10450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Geyer J, Wilke T, Petzinger E. 2006. The solute carrier family SLC10: more than a family of bile acid transporters regarding function and phylogenetic relationships. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 372:413–431. doi: 10.1007/s00210-006-0043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Geyer J, Döring B, Meerkamp K, Ugele B, Bakhiya N, Fernandes CF, Godoy JR, Glatt H, Petzinger E. 2007. Cloning and functional characterization of human sodium-dependent organic anion transporter (SLC10A6). J Biol Chem 282:19728–19741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma CM, Papenfort K, Pernitzsch SR, Mollenkopf H-J, Hinton JCD, Vogel J. 2011. Pervasive posttranscriptional control of genes involved in amino acid metabolism by the Hfq-dependent GcvB small RNA: GcvB regulon. Mol Microbiol 81:1144–1165. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zallot R, Agrimi G, Lerma-Ortiz C, Teresinski HJ, Frelin O, Ellens KW, Castegna A, Russo A, de Crécy-Lagard V, Mullen RT, Palmieri F, Hanson AD. 2013. Identification of mitochondrial coenzyme A transporters from Maize and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 162:581–588. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.218081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]