Abstract

Purpose

Younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) harboring NPM1 mutations without FLT3–internal tandem duplications (ITDs; NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype) are classified as better risk; however, it remains uncertain whether this favorable classification can be applied to older patients with AML with this genotype. Therefore, we examined the impact of age on the prognostic significance of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative status in older patients with AML.

Patients and Methods

Patients with AML age ≥ 55 years treated with intensive chemotherapy as part of Southwest Oncology Gorup (SWOG) and UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council (NCRI/MRC) trials were evaluated. A comprehensive analysis first examined 156 patients treated in SWOG trials. Validation analyses then examined 1,258 patients treated in MRC/NCRI trials. Univariable and multivariable analyses were used to determine the impact of age on the prognostic significance of NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITDs, and the NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype.

Results

Patients with AML age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype treated in SWOG trials had a significantly improved 2-year overall survival (OS) as compared with those without this genotype (70% v 32%; P < .001). Moreover, patients age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype had a significantly improved 2-year OS as compared with those age > 65 years with this genotype (70% v 27%; P < .001); any potential survival benefit of this genotype in patients age > 65 years was marginal (27% v 16%; P = .33). In multivariable analysis, NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remained independently associated with an improved OS in patients age 55 to 65 years (P = .002) but not in those age > 65 years (P = .82). These results were confirmed in validation analyses examining the NCRI/MRC patients.

Conclusion

NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remains a relatively favorable prognostic factor for patients with AML age 55 to 65 years but not in those age > 65 years.

INTRODUCTION

Frameshift mutations in nucleophosmin (NPM1) and internal tandem duplications (ITDs) in FMS-related tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) are two of the most common genetic abnormalities in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Patients with NPM1 mutations (NPM1 positive) have a favorable prognosis, whereas the opposite is true for patients with FLT3-ITDs.1–7 Several studies have shown that these mutations can be used to risk stratify patients with AML into four prognostic subgroups: NPM1 negative/FLT3-ITD negative; NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD positive; NPM1 negative/FLT3-ITD positive; and NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD negative. Patients with NPM1-negative/FLT3-ITD–positive genotype have a poor prognosis, whereas those with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype have a relatively good prognosis comparable to that of patients with favorable-risk cytogenetics.2–5 On the basis of these findings, the National Cancer Care Network and other groups classify patients with AML with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype as better risk, recommending that they be treated similarly to patients with favorable-risk cytogenetics.8,9

The prognostic impact of AML biomarkers may be age dependent, and the biomarkers used to risk stratify younger patients with AML may not be informative in older patients.10–13 For example, the frequency of favorable-risk cytogenetics decreases with age, and those patients age > 65 years harboring favorable-risk cytogenetics have a relatively poor prognosis.10–13 In the case of NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD negative, relatively few studies have examined the prognostic significance of this genotype in older patients with AML.14–17 Therefore, we examined the impact of age on the prognostic significance of NPM1-positive status and FLT3-ITDs in a large cohort of older adults with AML who were enrolled onto trials from SWOG and UK Medical Research Council/National Cancer Research Institute (MRC/NCRI). Our study demonstrated that NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remained a favorable prognostic factor in older patients age 55 to 65 years, but patients age > 65 years with this genotype had a relatively poor prognosis.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

The initial analyses examined 156 patients age ≥ 55 years treated in four SWOG trials (S9333, S9031, S9500, and S0106) from 1992 to 2009. To validate the results of the SWOG analyses, we examined 1,258 patients age ≥ 55 years who were treated in five MRC/NCRI trials (AML10, AML12, AML14, AML15, and AML16) from 1988 to 2010. Patients with acute promyelocytic leukemia were excluded. Studies were restricted to previously untreated patients with AML who received intensive chemotherapy. Institutional review boards of participating institutions approved all trials and use of materials for correlative studies. Patients provided consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Cytogenetics were centrally reviewed by respective SWOG or MRC/NCRI cytogenetics committees. Patients were classified as cytogenetically normal (CN) if no clonal abnormalities were detected in ≥ 20 metaphases analyzed. Molecular data for SWOG and MRC/NCRI have been previously reported.7,18–27 However, the impact of age on the prognostic significance of FLT3-ITDs and NPM1 mutations as presented in this study has not been previously described. Definitions of outcome, statistical methods, and details of therapy are available in the Appendix (online only).

RESULTS

Prognostic Significance of NPM1-Positive/FLT3-ITD–Negative Genotype in Older Patients Treated in SWOG Trials

All analyses were restricted to patients age ≥ 55 years, given that the clinical significance of both biomarkers is well established in younger patients.1–4 We first evaluated 156 patients with AML who received intensive chemotherapy as part of four SWOG trials (Appendix Table A1, online only). The median age of patients was 60 years (range, 55 to 83 years), with 33% and 24% of patients harboring NPM1 mutations and FLT3-ITDs, respectively. The complete remission (CR) rate, 2-year overall survival (OS), and 2-year relapse-free survival (RFS) for the entire cohort were 62%, 31%, and 32%, respectively. In multivariable analyses, increased age, unfavorable cytogenetics, and FLT3-ITDs were significantly associated with decreased OS and RFS (Appendix Table A2, online only).

Patients were then divided into two age groups: age 55 to 65 and > 65 years (Table 1). This age cutoff was chosen based on previous studies showing that the prognostic impact of favorable-risk cytogenetics was lost in patients age > 65 years.10,13 The prevalence of NPM1 mutations in patients age 55 to 65 years and in those age > 65 years was 32% and 34%, respectively. Both age groups displayed similar clinical characteristics (ie, WBC count, bone marrow blast percentage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status, cytogenetics, frequency of secondary AML, NPM1 mutations, and FLT3-ITDs). Patients age > 65 years were not enrolled onto S0106 or S9500 because of age restrictions in these trials. As compared with patients age 55 to 65 years, those age > 65 years had a lower 2-year OS (19% v 39%; P < .001), decreased 2-year RFS (19% v 38%; P = .007), and higher 1-year relapse rate (71% v 35%; P = .001). Multivariable analyses examining the two age groups showed that patients age 55 to 65 years without FLT3-ITD mutations had an improved OS (hazard ratio [HR], 0.37; P < .001) and RFS (HR, 0.30; P < .001) compared with those with FLT3-ITD mutations, whereas patients age > 65 years had such a uniformly poor prognosis that the prognostic impact of FLT3-ITD mutations was markedly attenuated. NPM1 mutations were not associated with a significant improvement in OS (age 55 to 65 years: HR, 0.80; P = .47; age > 65 years: HR, 0.83; P = .60) or RFS (age 55 to 65 years: HR, 0.70; P = .33; age > 65 years: HR, 0.81; P = .68) after adjusting for the other variables in either age cohort (Table 2).

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients With AML Treated on SWOG Protocols

| Characteristic | Age 55 to 65 Years (n = 98) |

Age > 65 Years (n = 58) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| WBC count | .14 | ||||

| Median | 20 | 29 | |||

| Range | 0-242 | 1-216 | |||

| BM blast percentage | .54 | ||||

| Median | 65 | 70 | |||

| Range | 20-100 | 0-99 | |||

| Secondary AML | 9 | 9 | 10 | 17 | .21 |

| Study | < .001 | ||||

| S0106 | 56 | 57 | 0 | 0 | |

| S9031 | 23 | 23 | 33 | 57 | |

| S3333 | 17 | 17 | 25 | 43 | |

| S9500 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sex | 1 | ||||

| Female | 46 | 47 | 28 | 48 | |

| Male | 52 | 53 | 30 | 52 | |

| ECOG PS | .29 | ||||

| 0-1 | 82 | 84 | 43 | 77 | |

| > 1 | 16 | 16 | 13 | 23 | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | |||

| Cytogenetics | .89 | ||||

| Favorable | 13 | 13 | 6 | 10 | |

| Intermediate | 52 | 53 | 35 | 60 | |

| Unfavorable | 27 | 28 | 14 | 24 | |

| Unknown | 6 | 6 | 3 | 5 | |

| Molecular markers | |||||

| NPM1 positive | 31 | 32 | 20 | 34 | .73 |

| FLT3-ITDs | 25 | 26 | 12 | 21 | .56 |

| NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD negative | 17 | 17 | 15 | 26 | .22 |

| Clinical outcome | |||||

| TRM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CR | 66 | 67 | 31 | 53 | .09 |

| 2-year OS | 39 | 19 | < .001 | ||

| 2-year RFS | 38 | 19 | .007 | ||

| 1-year relapse rate | 23 | 35 | 22 | 71 | .001 |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CR, complete remission; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITD, internal tandem duplication; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; TRM, therapy-related mortality.

Table 2.

Multivariable Analysis for OS and RFS of Patients With AML in SWOG Protocols

| Variable | OS |

RFS |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 55 to 65 Years |

Age > 65 Years |

Age 55 to 65 Years |

Age > 65 Years |

|||||||||

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Male sex | 1.58 | 0.96 to 2.51 | .07 | 0.82 | 0.45 to 1.47 | .50 | 0.97 | 0.51 to 1.87 | .94 | 0.50 | 0.18 to 1.34 | .17 |

| ECOG PS > 1 | 2.25 | 1.14 to 4.44 | .02 | 0.90 | 0.44 to 1.84 | .78 | 1.56 | 0.69 to 3.53 | .28 | 1.35 | 0.50 to 3.65 | .56 |

| WBC count | 1.01 | 0.95 to 1.07 | .74 | 0.97 | 0.88 to 1.06 | .46 | 1.06 | 0.98 to 1.15 | .18 | 0.97 | 0.83 to 1.13 | .72 |

| Platelet count | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.06 | .002 | 1.00 | 0.96 to 1.04 | .87 | 1.03 | 0.98 to 1.08 | .30 | 1.01 | 0.94 to 1.07 | .87 |

| BM blast percentage | 1.04 | 0.90 to 1.19 | .63 | 0.95 | 0.84 to 1.07 | .41 | 0.97 | 0.81 to 1.16 | .74 | 1.06 | 0.87 to 1.30 | .55 |

| Unfavorable cytogenetics | 3.53 | 1.90 to 6.56 | < .001 | —* | 1.34 | 0.49 to 3.65 | .56 | —* | ||||

| NPM1 positive | 0.80 | 0.44 to 1.46 | .47 | 0.83 | 0.41 to 1.69 | .60 | 0.70 | 0.34 to 1.45 | .33 | 0.81 | 0.30 to 2.22 | .68 |

| FLT3-ITD negative | 0.37 | 0.21 to 0.66 | < .001 | 0.79 | 0.37 to 1.70 | .55 | 0.30 | 0.15 to 0.60 | < .001 | 0.64 | 0.22 to 1.84 | .41 |

NOTE. ECOG PS was divided into two groups (≤ 1 v > 1). WBC and platelet counts were treated as continuous variables, and their HRs represent change per 1010/L increase. HR for BM blast percentage represents change per 10% increase. Cytogenetics was divided into two groups (unfavorable v all others). For this analysis, female sex, ECOG PS ≤ 1, all other cytogenetics, NPM1-negative status, and FLT3-ITD–positive status were used as references.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; ITD, internal tandem duplication; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

Because of small number of patients age > 65 years, cytogenetics could not be included in multivariable models for these patients.

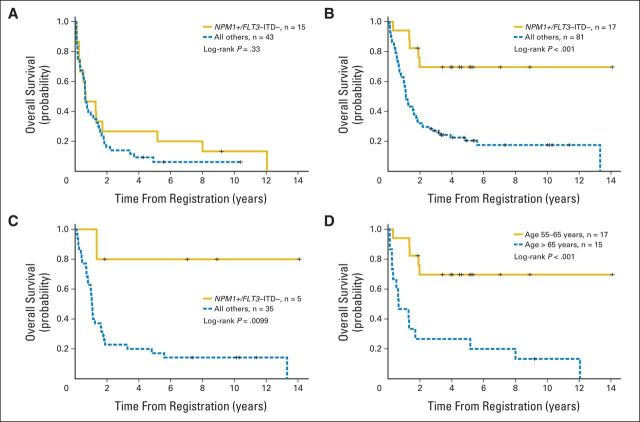

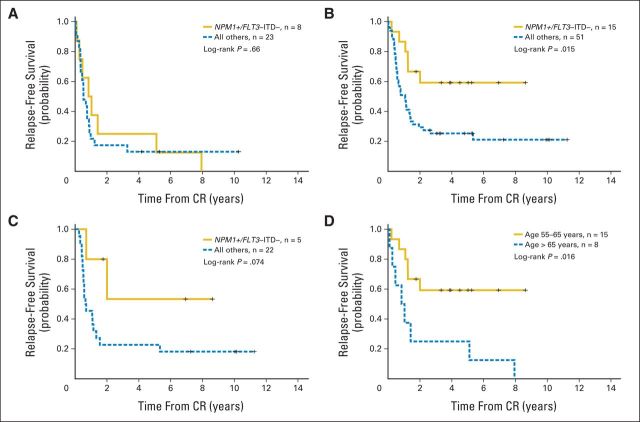

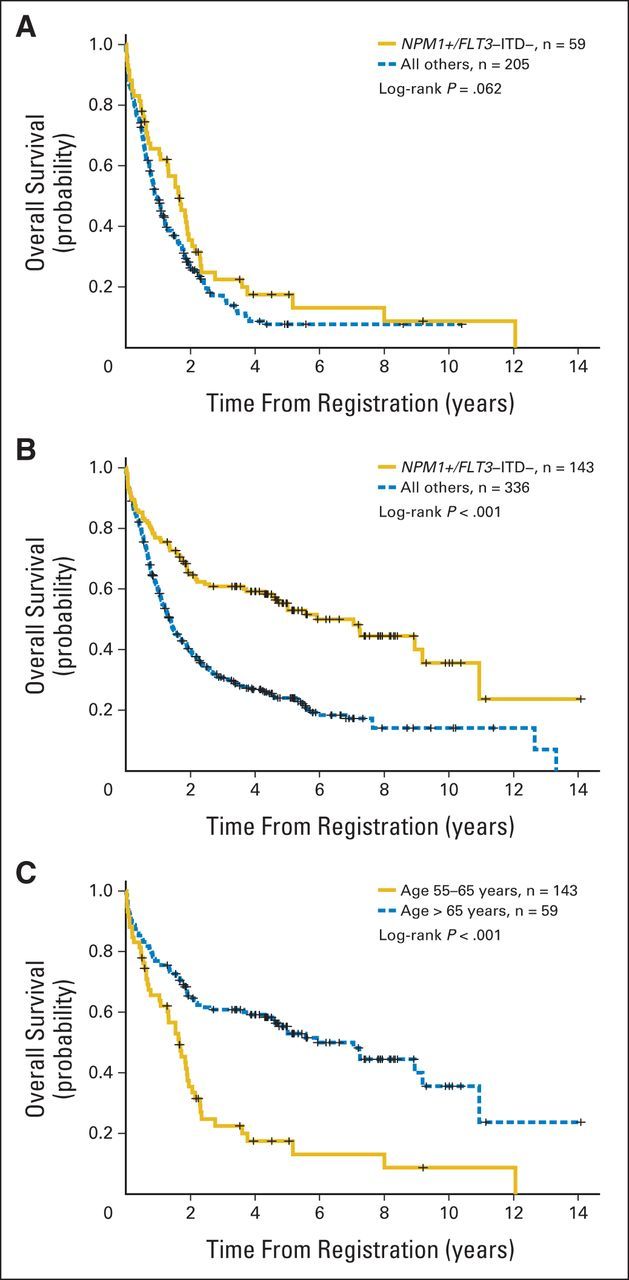

Many patients harbored both FLT3-ITDs and NPM1 mutations. To further control for the adverse prognostic effect of FLT3-ITDs on NPM1 mutations, we examined the prognostic impact of age in patients harboring the NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype. Patients with AML age > 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype did not have a significantly improved OS (P = .33; Fig 1A) or RFS (P = .66; Appendix Fig A1A, online only) as compared with those patients without this genotype. Conversely, patients age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype displayed a significantly improved OS (P < .001; Fig 1B) and RFS (P = .015; Appendix Fig A1B, online only) as compared with those without this genotype. Moreover, the overall prognosis for patients age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype was similar to that reported for younger patients with this genotype.2–4 Multivariable models adjusting for other known prognostic covariates (Table 3) showed that NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remained independently associated with an improved OS for patients age 55 to 65 years (HR, 0.20; P = .002) but not those age > 65 years (HR, 0.91; P = .82). In a multivariable model with all patients, the P value for the interaction between age and NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype was .014, indicating that the prognostic impact of this genotype significantly varies based on the age of the patient. To further control for the potential impact of different therapies, we also evaluated the prognostic significance of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in only those patients enrolled onto protocols S9031 and S9333, because these two trials were used to treat both age groups. Unlike patients age > 65 years treated in these same protocols (Fig 1A), patients in S9031 and S9333 age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype displayed a significantly improved OS compared with those without this genotype (Fig 1C; P = .0099), indicating that treatment differences between the two age groups were not responsible for the age-related findings.

Fig 1.

Overall survival (OS) of SWOG patients age (A) > 65 and (B) 55 to 65 years stratified by NPM1-positive/FLT3–internal tandem duplication (ITD) –negative genotype and (C) 55 to 65 years treated on SWOG protocols 9031 and 9333 stratified by NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype. (D) OS for patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype stratified by two age groups.

Table 3.

Multivariable Analysis for OS of Patients With AML Age 55 to 65 and > 65 Years Treated on SWOG Protocols

| Variable | Age 55 to 65 Years |

Age > 65 Years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD negative | 0.20 | 0.07 to 0.55 | .002 | 0.91 | 0.39 to 2.10 | .82 |

| Male sex | 1.39 | 0.85 to 2.28 | .19 | 0.72 | 0.40 to 1.30 | .28 |

| ECOG PS ≤ 1 | 1.97 | 1.03 to 3.79 | .041 | 1.15 | 0.53 to 2.46 | .73 |

| WBC count | 1.02 | 0.97 to 1.08 | .48 | 0.98 | 0.90 to 1.08 | .71 |

| Platelet count | 1.03 | 1.01 to 1.05 | .004 | 1.00 | 0.96 to 1.05 | .82 |

| BM blast percentage | 1.00 | 0.88 to 1.14 | .98 | 0.95 | 0.83 to 1.08 | .45 |

| Unfavorable cytogenetics | 3.13 | 1.76 to 5.57 | < .001 | 3.82 | 1.74 to 8.39 | < .001 |

NOTE. ECOG PS was divided into two groups (≤ 1 v > 1). WBC and platelet counts were treated as continuous variables, and their HRs represent change per 1010/L increase. HR for BM blast percentage represents change per 10% increase. Cytogenetics was divided into two groups (unfavorable v all others). For this analysis, female sex, PS ≤ 1, all other cytogenetics, three other genotypes (ie, NPM1 negative/FLT3-ITD negative, NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD positive, NPM1 negative/FLT3-ITD positive) were used as references.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; ITD, internal tandem duplication; OS, overall survival.

We then directly compared the clinical characteristics and outcomes of the two age groups of patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype with one another (Table 4). Patients age > 65 years had a significantly decreased 2-year OS (P < .001; Fig 1D) and 2-year RFS (P = .016; Appendix Fig A1C, online only) as compared with patients age 55 to 65 years with this genotype. In addition, the older patients had a decreased CR rate (53% v 88%; P = .049) and an increased 1-year relapse rate (47% v 12%; P = .049) but no significant increase in early treatment-related mortality. The vast majority of patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in both age groups had intermediate-risk cytogenetics (age 55 to 65 years, 88%; > 65 years, 93%; P = 1.0). Moreover, the frequency of CN in patients harboring NPM1 mutations and FLT3-ITDs was similar in patients age 55 to 65 and > 65 years (29% v 35%, respectively; P = .6). Because mutations in DNMT3A and IDH1/2 have been reported to be associated with adverse outcomes for NPM1-positive patients,26,28,29 we evaluated the frequency of these mutations in the patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype. Overall, the frequency of DNMT3A and IDH1/2 mutations were similar between the two age groups, suggesting that they were not responsible for the age-dependent findings (Table 4).

Table 4.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of SWOG Patients With NPM1-Positive/FLT3-ITD–Negative Genotype

| Characteristic | Age 55 to 65 Years (n = 17) |

Age > 65 Years (n = 15) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| WBC count | .15 | ||||

| Median | 24 | 43 | |||

| Range | 5-70 | 6-80 | |||

| BM blast percentage | .04 | ||||

| Median | 69 | 82 | |||

| Range | 25-85 | 0-98 | |||

| Secondary AML | 0 | 0 | 2 | 13 | .23 |

| Study | < .001 | ||||

| S0106 | 11 | 65 | 0 | 0 | |

| S9031 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 60 | |

| S3333 | 4 | 24 | 6 | 40 | |

| S9500 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sex | 1 | ||||

| Female | 8 | 47 | 8 | 53 | |

| Male | 9 | 53 | 7 | 47 | |

| ECOG PS | .18 | ||||

| 0-1 | 12 | 71 | 13 | 93 | |

| > 1 | 5 | 29 | 1 | 7 | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | |||

| Cytogenetics | 1 | ||||

| Favorable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intermediate | 15 | 88 | 14 | 93 | |

| Unfavorable | 2 | 12 | 1 | 7 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other molecular markers | |||||

| IDH1/2 | 5 | 33 | 4 | 27 | 1 |

| DNMT3A | 4 | 27 | 5 | 36 | .70 |

| Clinical outcome | |||||

| TRM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| CR | 15 | 88 | 8 | 53 | .049 |

| 2-year OS | 70 | 27 | < .001 | ||

| 2-year RFS | 67 | 25 | .016 | ||

| 1-year relapse rate | 12 | 47 | .049 | ||

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CR, complete remission; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITD, internal tandem duplication; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; TRM, therapy-related mortality.

Prognostic Significance of NPM1-Positive/FLT3-ITD–Negative Genotype in Older Patients Treated in MRC/NCRI Trials

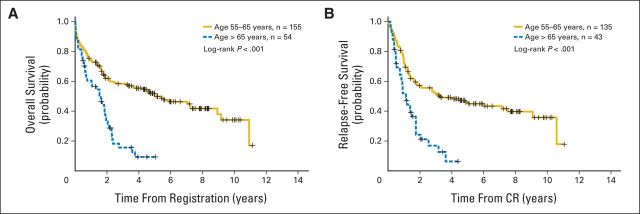

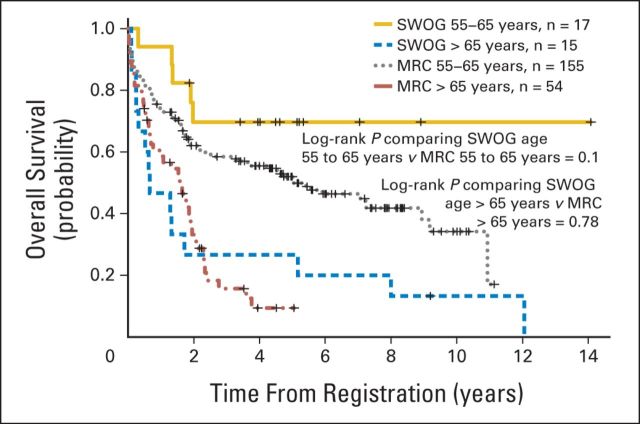

To validate these findings, we examined an independent population of 1,258 patients with AML age ≥ 55 years who received intensive chemotherapy as part of the MRC/NCRI trials. As with the SWOG cohort, patients were divided into two age groups: 55 to 65 and > 65 years (Appendix Table A3, online only). Patients age > 65 years had a lower OS, decreased RFS, and higher 1-year relapse rate. We then compared patients age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype with those age > 65 years with this genotype (Appendix Table A4, online only). As demonstrated in the SWOG analyses, patients with AML age > 65 years with this genotype had a significantly decreased 2-year OS (P < .001; Fig 2A) and 2-year RFS (P < .001; Fig 2B) when compared with patients age 55 to 65 years. Moreover, the relatively poor OS for the older MRC/NCRI patients with this genotype paralleled that found in the SWOG patients (Appendix Fig A2, online only).

Fig 2.

(A) Overall and (B) relapse-free survival for UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3–internal tandem duplication–negative genotype stratified by two age groups. CR, complete remission.

Prognostic Significance of NPM1-Positive/FLT3-ITD–Negative Genotype in Older Patients With CN-AML in Combined SWOG and MRC/NCRI Cohorts

An analysis using both SWOG and MCR/NCRI patients evaluated the prognostic significance of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in 743 patients with CN-AML. Patients age > 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype displayed only a modest, if any, improvement in 2-year OS (36% v 26%; P = .062) as compared with those without this genotype. Moreover, the long-term OS for patients age > 65 years with CN-AML was universally poor, such that < 20% of the patients with CN-AML were expected to be alive at 5 years, regardless of their genotype. Conversely, patients with CN-AML age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype retained a favorable OS as compared with those without this genotype (65% v 40%; P < .001; Appendix Fig A3, online only). In a multivariable analysis of the combined cohorts, the P value for the interaction between age and favorable genotype was .032, indicating that the prognostic significance of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remained significantly different in the two age groups.

DISCUSSION

Analyses from this large retrospective study demonstrate that patients age 55 to 65 years harboring NPM1 mutations and FLT3-ITDs have a significantly improved survival as compared with those without this genotype. Furthermore, the outcome for these patients resembles that seen in younger adults.2–5 However, patients age > 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype have uniformly poor survival regardless of the presence of this favorable genotype. Additional analyses indicate that the relatively poor survival for patients age > 65 years is not the result of differences in treatment or early treatment-related mortality between the two age groups. Rather, most of the age-related survival differences seem to be attributed to a significantly lower CR and higher 1-year relapse rate as compared with those age 55 to 65 years. These findings suggest that other age-related factors are likely contributing to the poor outcome in patients age > 65 years.

As in studies of younger patients, most patients age > 55 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype have CN, and we could not demonstrate any significant difference in the frequency of either CN or other cytogenetic risk groups between these two age groups. We also examined the frequency of DNMT3A and IDH1/2 mutations in the NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype, given that these mutations have been associated with adverse outcomes for NPM1-positive patients.26,28,29 DNMT3A and IDH1/2 mutations displayed similar frequencies in both age groups, suggesting that these mutations were likely not responsible for the observed age-dependent findings for patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype.

Two previous studies have examined the impact of age on the prognostic significance of NPM1 mutations, without further stratifying patients into NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype group.14,16 Similar to our patients, those in these two studies received intensive chemotherapy. However, both studies used an age cutoff of ≥ 60 years to define older patients. The first study evaluated 144 patients with CN-AML; only half had information on FLT3-ITD status. In multivariable analysis, NPM1 mutations were associated with a higher CR rate but only marginal improvement in OS.16 The second study examined a total of 148 patients with CN-AML.14 Compared with patients without NPM1 mutations, NPM1-positive patients had an improved 3-year disease-free survival (23% v 10%; P < .001) and OS (35% v 8%; P < .01). However, despite this significant improvement in clinical outcomes, patients with NPM1 mutations in the second study had a relatively poor prognosis when compared with younger adults (age < 55 years), and in fact, the clinical outcomes for patients age ≥ 60 years were not dramatically different from our results for patients with CN-AML age ≥ 65 years. Some of the potential differences in results between our results and theirs may be attributed to the use of a different age cutoff; many of their older patients would have been included in our cohort of patients age 55 to 65 years, thus potentially leading to a relative improvement in outcome for their older patients. However, subset analyses from the previously reported study suggested that most of the beneficial effect from NPM1 mutations was restricted to those patients age ≥ 70 years and was not observed in those age 60 to 69 years.14 As acknowledged by the investigators, the reason for this unexpected finding was unclear and could not be attributed to differences in gene expression signatures. Certainly, other molecular markers (eg, DNMT3A and IDH1/2)26,29 could explain their findings, if the frequencies of these mutations were different in the examined age groups (ie, 60 to 69 v ≥ 70 years). In the case of our study, we did not observe significant differences in the frequency of DNMT3A and IDH1/2 mutations between those age 55 to 65 versus > 65 years. Nevertheless, there is a need for additional studies to better define and understand the impact of age, as well as other factors, on the biology of NPM1 mutations.

Four studies have evaluated the prognostic impact of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in older patients (age ≥ 60 years).12,15,17,30 The first study suggested that NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype was only associated with improvement in OS in older patients receiving all-trans-retinoic acid in addition to chemotherapy.15 A second study examined a relatively limited number of patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype. In this study, patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype who received intensive chemotherapy had a higher CR rate but no significant improvement in OS.17 The third study, one of the largest, examined patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype treated as part of the German Acute Leukemia Group (GALG) trials.12 In this study, the investigators found that patients age > 60 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype had a significantly lower OS as compared with patients age < 60 years with the same genotype. However, the 2-year OS of patients age > 60 years with this genotype was > 50%, which is a relatively favorable outcome and approximately double the 2-year OS for the SWOG patients age > 65 years. A possible explanation for the more favorable outcome in the older patients with AML from the GALG study is that approximately half of their older patients were ≤ 65 years (median, 66 years) and thus would have fallen within our cohort of those age 55 to 65 years. However, we cannot rule out potential treatment differences that may explain the higher OS and RFS in their older cohort.12

A recently published study by the MRC/NCRI group evaluated the prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations, FLT3-ITDs, and NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in patients age > 60 years who were treated with intensive and nonintensive chemotherapies.30 The MRC/NCRI investigators reported that NPM1 mutations by themselves were associated with a superior CR rate in older patients with AML treated with intensive chemotherapy but were not associated with a significant improvement in OS. Additional analyses evaluated the older patients stratified by the four NPM1/FLT3-ITD genotypes, demonstrating a significant improvement in OS for those with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype who were treated with intensive chemotherapy. However, this improved OS for patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype was not markedly better than the OS for patients without this genotype, such that the 3-year OS for patients age > 60 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype was only 22%. These previous MRC/NCRI analyses did not include a substantial number of patients age 55 to 60 years, nor did these analyses examine the prognostic impact of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype on OS stratified into the two age cohorts described in our report. As part of our validation study, we also examined patients treated with intensive chemotherapy in the MRC/NCRI trials, but we used an age cutoff of 55 years and stratified the MRC/NCRI patients into two populations as was previously done in the initial SWOG analyses (55 to 65 v > 65 years). As demonstrated in the SWOG patients, MRC/NCRI patients age 55 to 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype displayed a good prognosis, whereas those age > 65 years had a poor prognosis.

The purpose of our study was to determine the impact that age may have on the prognostic significance of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in older adults. One potential limitation to our study is that data regarding allogeneic stem-cell transplantation (alloSCT) were not systematically collected. Therefore, the effect of alloSCT on the outcome of older patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remains unknown and should be investigated in prospective clinical trials. In our analysis, older patients with AML were stratified into two age groups using a cutoff of 65 years, given that the beneficial impact of favorable-risk cytogenetics has been shown to be retained in those with AML age 55 to 65 years but lost in those age > 65 years.10,13 As with favorable-risk cytogenetics, there was a marked difference in survival between those age 55 to 65 versus > 65 years among patients with AML with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype. Moreover, the OS for those age > 65 years was similar to that reported for adverse cytogenetics in younger adults, indicating that patients age > 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype should not be considered favorable risk when treated with standard therapy. Given that a majority of patients with AML are age ≥ 55 years at diagnosis,31 the findings in our report can be used to better inform a large number of patients about their therapeutic options.

In conclusion, our report describes one of the largest and most comprehensive evaluations of NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype in older adults with AML treated with intensive chemotherapy. The findings indicate that NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype remains a favorable risk factor for patients with AML age 55 to 65 years but should not be considered a favorable risk factor for patients age > 65 years, at least not for those treated with standard induction followed by conventional consolidation. In many ways, these findings are consistent with the results from our previous study examining other good-risk prognostic factors in older patients.10,13 Given the results from this study, we propose that patients with AML age > 65 years with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype should not be classified as better risk. Moreover, patients age > 65 years with this genotype should be counseled about their overall poor prognosis and, if appropriate, be considered for novel clinical trials or even alloSCT in first CR.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Treatment Regimens for Patients in SWOG Trials

SWOG patients were treated in trials S9333, S9031, S9500, and S0106. All SWOG patients received cytarabine-plus-daunorubincin (ie, 7 + 3) induction regimens. Patients from S9333 who were randomly assigned to the mitoxantrone-plus-etoposide arm were excluded because of the inferiority of this arm. In the case of patients from S9500, high-dose cytarabine (HiDAC) was incorporated into the induction during days 8 to 10. Cytarabine plus daunorubincin (S9031 and S9333) or HiDAC (9500 and S0106) was used for consolidation. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin, either during induction, consolidation, and/or postconsolidation, was administered to a subgroup of patients enrolled onto S0106 as previously described.

Definitions of Outcomes and Statistical Methods

Overall survival (OS) was measured from the date of registration to date of death resulting from any cause, with patients last known to be alive censored at the date of last contact. Relapse-free survival (RFS) was measured from the date of complete remission (CR) to the date of first relapse or death resulting from any cause, with patients last known to be alive without report of relapse censored at the date of last contact. Therapy-related mortality was defined as death within 28 days after initiation of therapy. Cox regression models included sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (≤ 1 v > 2), and cytogenetic risk (unfavorable v all others), as well as quantitative covariates such as age, WBC count, platelet count, and marrow blast percentage. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare quantitative covariates, and Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical covariates. Logistic regression was used to assess associations with CR. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate OS and RFS, and Cox regression models were used to assess associations with these outcomes.

Table A1.

Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes of SWOG Patients (n = 156)

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 60 | |

| Range | 55-83 | |

| WBC count | ||

| Median | 22 | |

| Range | 0.5-243 | |

| Platelets | ||

| Median | 54 | |

| Range | 3-1,052 | |

| BM blast percentage | ||

| Median | 68 | |

| Range | 0-100 | |

| Secondary AML | 19 | 12 |

| Study | ||

| S0106 | 56 | 36 |

| S9031 | 56 | 36 |

| S9333 | 42 | 27 |

| S9500 | 2 | 1 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 74 | 47 |

| Male | 82 | 53 |

| ECOG PS | ||

| 0-1 | 125 | 81 |

| > 1 | 29 | 19 |

| Cytogenetics | ||

| Favorable | 19 | 12 |

| Intermediate | 87 | 56 |

| Unfavorable | 41 | 26 |

| Unknown | 9 | 6 |

| Molecular markers | ||

| NPM1 positive | 51 | 33 |

| FLT3-ITDs | 37 | 24 |

| NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD negative | 32 | 21 |

| Clinical outcome | ||

| TRM | 0 | 0 |

| CR | 97 | 62 |

| 2-year OS | 31 | |

| 2-year RFS | 32 | |

| 1-year relapse rate | 45 | 46 |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CR, complete remission; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITD, internal tandem duplication; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; TRM, therapy-related mortality.

Table A2.

Multivariable Analysis for OS and RFS of Patients With AML Treated on SWOG Protocols

| Variable | OS |

RFS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P | HR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age, years | 1.06 | 1.03 to 1.09 | < .001 | 1.04 | 1.00 to 1.08 | .05 |

| Male sex | 1.16 | 0.84 to 1.69 | .43 | 0.85 | 0.51 to 1.40 | .52 |

| ECOG PS > 1 | 1.45 | 0.87 to 2.94 | .15 | 1.53 | 0.82 to 2.88 | .18 |

| WBC count | 1.01 | 0.96 to 1.06 | .71 | 1.04 | 0.97 to 1.12 | .24 |

| Platelet count | 1.02 | 1.00 to 1.04 | .02 | 1.03 | 0.99 to 1.06 | .12 |

| BM blast percentage | 0.87 | 0.88 to 1.06 | .47 | 0.98 | 0.86 to 1.11 | .75 |

| Unfavorable cytogenetics | 4.2 | 2.6 to 6.8 | < .001 | 2.30 | 1.08 to 4.87 | .03 |

| NPM1 positive | 1.04 | 0.66 to 1.65 | .96 | 0.84 | 0.48 to 1.46 | .53 |

| FLT3-ITDs | 2.10 | 1.37 to 3.21 | < .001 | 2.81 | 1.64 to 4.79 | < .001 |

NOTE. ECOG PS was divided into two groups (≤ 1 v > 1). WBC and platelet counts were treated as continuous variables, and their HRs represent change per 1010/L increase. Analysis used blast percentage with 10% increments. Cytogenetics was divided into two groups (unfavorable v all others). For this analysis, female sex, PS ≤ 1, all other cytogenetics, NPM1-negative status, and FLT3-ITD–negative status were used as references.

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; HR, hazard ratio; ITD, internal tandem duplication; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival.

Table A3.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of NCRI/MRC Patients

| Characteristic | Age 55 to 65 Years (n = 810) |

Age > 65 Years (n = 448) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| WBC count | .02 | ||||

| Median | 13 | 8 | |||

| Range | 0-467 | 0-337 | |||

| BM blast percentage | .06 | ||||

| Median | 65 | 60 | |||

| Range | 0-100 | 4-100 | |||

| Secondary AML | 101 | 12 | 70 | 16 | .0015 |

| Sex | .11 | ||||

| Female | 321 | 40 | 157 | 35 | |

| Male | 489 | 60 | 291 | 65 | |

| ECOG PS | .84 | ||||

| 0-1 | 735 | 91 | 405 | 90 | |

| > 1 | 75 | 9 | 43 | 10 | |

| Cytogenetics | .36 | ||||

| Favorable | 57 | 7 | 24 | 5 | |

| Intermediate | 511 | 63 | 275 | 61 | |

| Unfavorable | 182 | 22 | 106 | 24 | |

| Unknown | 60 | 7 | 43 | 10 | |

| Molecular markers | |||||

| NPM1 positive | 255 | 31 | 93 | 21 | < .001 |

| FLT3-ITDs | 160 | 20 | 75 | 17 | .2 |

| NPM1 positive/FLT3-ITD negative | 155 | 19 | 54 | 12 | .0012 |

| Clinical outcome | |||||

| TRM | 76 | 9 | 55 | 12 | .12 |

| CR | 604 | 75 | 299 | 67 | .004 |

| 2-year OS | 39 | 24 | < .001 | ||

| 2-year RFS | 37 | 18 | < .001 | ||

| 1-year relapse rate | 218 | 36 | 156 | 52 | < .001 |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CR, complete remission; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITD, internal tandem duplication; NCRI/MRC, UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; TRM, therapy-related mortality.

Table A4.

Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of NCRI/MRC Patients With NPM1-Positive/FLT3-ITD–Negative Genotype

| Characteristic | Age 55 to 65 Years (n = 155) |

Age > 65 Years (n = 54) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| WBC count | .50 | ||||

| Median | 28 | 22 | |||

| Range | 1-316 | 1-239 | |||

| BM blast percentage | .89 | ||||

| Median | 79 | 78 | |||

| Range | 2-100 | 16-100 | |||

| Secondary AML | 7 | 5 | 4 | 7 | .61 |

| Possibly secondary | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Study | < .001 | ||||

| AML10 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| AML12 | 44 | 28 | 0 | 0 | |

| AML14 | 14 | 9 | 13 | 24 | |

| AML15 | 70 | 45 | 3 | 6 | |

| AML16 | 25 | 16 | 38 | 70 | |

| Sex | 1 | ||||

| Female | 67 | 43 | 23 | 43 | |

| Male | 88 | 57 | 31 | 57 | |

| ECOG PS | .16 | ||||

| 0-1 | 138 | 89 | 44 | 81 | |

| > 1 | 17 | 11 | 10 | 19 | |

| Cytogenetics | .10 | ||||

| Favorable | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Intermediate | 145 | 94 | 51 | 94 | |

| Unfavorable | 3 | 2 | 3 | 6 | |

| Unknown | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| Clinical outcome | |||||

| TRM | 12 | 8 | 6 | 11 | .41 |

| CR | 135 | 87 | 43 | 80 | .19 |

| 2-year OS | 62 | 33 | < .001 | ||

| 2-year RFS | 57 | 24 | < .001 | ||

| 1-year relapse rate | 28 | 21 | 16 | 37 | .041 |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukemia; BM, bone marrow; CR, complete remission; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITD, internal tandem duplication; NCRI/MRC, UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council; OS, overall survival; RFS, relapse-free survival; TRM, therapy-related mortality.

Fig A1.

Relapse-free survival (RFS) of SWOG patients age (A) > 65 and (B) 55 to 65 years stratified by NPM1-positive/FLT3–internal tandem duplication (ITD) –negative genotype and (C) 55 to 65 years treated on SWOG protocols 9031 and 9333 stratified by NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype. (D) RFS for patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype stratified by two age groups. CR, complete remission.

Fig A2.

Comparison of overall survival for patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3–internal tandem duplication–negative genotype treated in SWOG and Medical Research Council (MRC) trials.

Fig A3.

Overall survival (OS) in combined SWOG and UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council cohorts of patients with cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia age (A) > 65 and (B) 55 to 65 years stratified by NPM1-positive/FLT3–internal tandem duplication (ITD) –negative genotype. (C) OS for patients with NPM1-positive/FLT3-ITD–negative genotype stratified by two age groups.

Footnotes

Supported in part by Public Health Service Cooperative Agreement Grants No. CA32102, CA38926, CA20319, CA073590, CA160872 and CA12213 from the Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program, National Cancer Institute, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at www.jco.org.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Fabiana Ostronoff, Derek L. Stirewalt

Financial support: Derek L. Stirewalt

Administrative support: Derek L. Stirewalt

Provision of study materials or patients: Derek L. Stirewalt

Collection and assembly of data: Fabiana Ostronoff, Megan Othus, Derek L. Stirewalt

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Prognostic Significance of NPM1 Mutations in the Absence of FLT3–Internal Tandem Duplication in Older Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A SWOG and UK National Cancer Research Institute/Medical Research Council Report

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Fabiana Ostronoff

No relationship to disclose

Megan Othus

No relationship to disclose

Michelle Lazenby

No relationship to disclose

Elihu Estey

No relationship to disclose

Frederick R. Appelbaum

Honoraria: Amgen, Celator, National Marrow Donor Program, Neumedicines

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Celator, National Marrow Donor Program, Neumedicines

Anna Evans

No relationship to disclose

John Godwin

No relationship to disclose

Amanda Gilkes

No relationship to disclose

Kenneth J. Kopecky

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Celator

Research Funding: Bristol-Myers Squibb

Alan K. Burnett

No relationship to disclose

Alan F. List

No relationship to disclose

Min Fang

Research Funding: Affymetrix (Inst)

Vivian G. Oehler

Consulting or Advisory Role: ARIAD Pharmaceuticals

Stephen H. Petersdorf

No relationship to disclose

Era L. Pogosova-Agadjanyan

No relationship to disclose

Jerald P. Radich

Consulting or Advisory Role: Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Incyte

Research Funding: novartis

Cheryl L. Willman

No relationship to disclose

Soheil Meshinchi

No relationship to disclose

Derek L. Stirewalt

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1.Falini B, Mecucci C, Tiacci E, et al. Cytoplasmic nucleophosmin in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:254–266. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dohner K, Schlenk RF, Habdank M, et al. Mutant nucleophosmin (NPM1) predicts favorable prognosis in younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia and normal cytogenetics: Interaction with other gene mutations. Blood. 2005;106:3740–3746. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schnittger S, Schoch C, Kern W, et al. Nucleophosmin gene mutations are predictors of favorable prognosis in acute myelogenous leukemia with a normal karyotype. Blood. 2005;106:3733–3739. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thiede C, Koch S, Creutzig E, et al. Prevalence and prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in 1485 adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) Blood. 2006;107:4011–4020. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Krauter J, et al. Mutations and treatment outcome in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1909–1918. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiede C. Analysis of FLT3-activating mutations in 979 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia: Association with FAB subtypes and identification of subgroups with poor prognosis. Blood. 2002;99:4326–4335. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.12.4326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kottaridis PD, Gale RE, Frew ME, et al. The presence of a FLT3 internal tandem duplication in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) adds important prognostic information to cytogenetic risk group and response to the first cycle of chemotherapy: Analysis of 854 patients from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council AML 10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2001;98:1752–1759. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Nicolet D, et al. Prognostic significance of the European LeukemiaNet standardized system for reporting cytogenetic and molecular alterations in adults with acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4515–4523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.4738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Acute Myeloid Leukemia (version 2 2014) http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Appelbaum FR, Gundacker H, Head DR, et al. Age and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:3481–3485. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meshinchi S, Alonzo TA, Stirewalt DL, et al. Clinical implications of FLT3 mutations in pediatric AML. Blood. 2006;108:3654–3661. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Büchner T, Berdel WE, Haferlach C, et al. Age-related risk profile and chemotherapy dose response in acute myeloid leukemia: A study by the German Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:61–69. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Appelbaum FR, Kopecky KJ, Tallman MS, et al. The clinical spectrum of adult acute myeloid leukaemia associated with core binding factor translocations. Br J Haematol. 2006;135:165–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker H, Marcucci G, Maharry K, et al. Favorable prognostic impact of NPM1 mutations in older patients with cytogenetically normal de novo acute myeloid leukemia and associated gene- and microRNA-expression signatures: A Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:596–604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlenk RF, Döhner K, Kneba M, et al. Gene mutations and response to treatment with all-trans retinoic acid in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Results from the AMLSG Trial AML HD98B. Haematologica. 2009;94:54–60. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dang H, Jiang A, Kamel-Reid S, et al. Prognostic value of immunophenotyping and gene mutations in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia with normal karyotype. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholl S, Theuer C, Scheble V, et al. Clinical impact of nucleophosmin mutations and Flt3 internal tandem duplications in patients older than 60 yr with acute myeloid leukaemia. Eur J Haematol. 2008;80:208–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2007.01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godwin JE, Kopecky KJ, Head DR, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in elderly patients with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia: A Southwest Oncology Group study (9031) Blood. 1998;91:3607–3615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson JE, Kopecky KJ, Willman CL, et al. Outcome after induction chemotherapy for older patients with acute myeloid leukemia is not improved with mitoxantrone and etoposide compared to cytarabine and daunorubicin: A Southwest Oncology Group study. Blood. 2002;100:3869–3876. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-12-0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersdorf SH, Rankin C, Head DR, et al. Phase II evaluation of an intensified induction therapy with standard daunomycin and cytarabine followed by high dose cytarabine for adults with previously untreated acute myeloid leukemia: A Southwest Oncology Group study (SWOG-9500) Am J Hematol. 2007;82:1056–1062. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersdorf SH, Kopecky KJ, Slovak M, et al. A phase 3 study of gemtuzumab ozogamicin during induction and postconsolidation therapy in younger patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:4854–4860. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-466706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hann IM, Stevens RF, Goldstone AH, et al. Randomized comparison of DAT versus ADE as induction chemotherapy in children and younger adults with acute myeloid leukemia: Results of the Medical Research Council's 10th AML trial (MRC AML10)—Adult and Childhood Leukaemia Working Parties of the Medical Research Council. Blood. 1997;89:2311–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burnett AK, Hills RK, Green C, et al. The impact on outcome of the addition of all-trans retinoic acid to intensive chemotherapy in younger patients with nonacute promyelocytic acute myeloid leukemia: Overall results and results in genotypic subgroups defined by mutations in NPM1, FLT3, and CEBPA. Blood. 2010;115:948–956. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burnett AK, Hills RK, Milligan D, et al. Identification of patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia who benefit from the addition of gemtuzumab ozogamicin: Results of the MRC AML15 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:369–377. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.4310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gale RE, Hills R, Kottaridis PD, et al. No evidence that FLT3 status should be considered as an indicator for transplantation in acute myeloid leukemia (AML): An analysis of 1135 patients, excluding acute promyelocytic leukemia, from the UK MRC AML10 and 12 trials. Blood. 2005;106:3658–3665. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ostronoff F, Othus M, Ho PA, et al. Mutations in the DNMT3A exon 23 independently predict poor outcome in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia: A SWOG report. Leukemia. 2013;27:238–241. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ho PA, Alonzo TA, Kopecky KJ, et al. Molecular alterations of the IDH1 gene in AML: A Children's Oncology Group and Southwest Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 2010;24:909–913. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thol F, Damm F, Lüdeking A, et al. Incidence and prognostic influence of DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2889–2896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.4894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paschka P, Schlenk RF, Gaidzik VI, et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations are frequent genetic alterations in acute myeloid leukemia and confer adverse prognosis in cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukemia with NPM1 mutation without FLT3 internal tandem duplication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3636–3643. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.3762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lazenby M, Gilkes AF, Marrin C, et al. The prognostic relevance of flt3 and npm1 mutations on older patients treated intensively or non-intensively: A study of 1312 patients in the UK NCRI AML16 trial. Leukemia. 2014;28:1953–1959. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Cancer Institute. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Leukemia. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/leuks.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.