Abstract

Serendipity is a pleasant surprise of finding a particularly useful information while not looking for it. Significant historic events occurring as a result of serendipity include the discovery of the law of buoyancy (Archimedes principle) by the Greek mathematician Archimedes, of the Americas by Christopher Columbus and of gravity by Sir Isaac Newton. The role of serendipity in science has been immensely beneficial to mankind. A host of important discoveries in medical science owe their origin to serendipity of which perhaps the most famous is the story of Sir Alexander Fleming and his discovery of Penicillin. In the field of dermatology, serendipity has been responsible for major developments in the therapy of psoriasis, hair disorders, aesthetic dermatology and dermatosurgery. Besides these many other therapeutic modalities in dermatology were born as a result of such happy accidents.

Keywords: Dermatology, science, serendipity

What was known?

Serendipity has played an important role in all aspects of life including Science, Medicine and Dermatology. A large number of therapies in Dermatology are used for indications which were accidentally discovered as a result of serendipity.

Introduction

From its very inception human history is replete with the story of unplanned or unforeseen incidents which have occurred in spite of lack of intention or necessity. Such events are called accidents. Though the word accident generally implies a negative event, some do have a happy outcome. Such a happy accident is described as “Serendipity”. According to the Oxford English dictionary Serendipity is “the occurrence and development of events by chance in a happy or beneficial way.”[1] It has also been defined as a “happy accident or pleasant surprise; specifically, the accident of finding something good or useful while not specifically searching for it.”[2] The discovery of the law of buoyancy (Archimedes principle) by the Greek mathematician Archimedes, of the Americas by Christopher Columbus and of gravity by Sir Isaac Newton are a few of the most famous examples of serendipity.

Origin

The original source of the word “Serendipity” is controversial. It was first used by Sir Horace Walpole in a letter written to Horce Mann on 28th January, 1754 while referring to accidental discoveries. He claimed that he derived the word from the ‘The Three Princes of Serendip”, a Persian fairy tale whose heroes “were always making discoveries, by accidents and sagacity, of things they were not in quest of”. However, the source of the word “Serendip” is not clear. The various sources suggested are: Serendip (old name for Sri Lanka); Sarandib in Arabic (adopted from Tamil “Serendeevu”); “Suvarnadweepa” (golden island) and “Simhaladvipa” (Lion Island) in Sanskrit.[3]

Types of Serendipity

Serendipity can occur under various circumstances. “Serendipity is the faculty of finding things we did not know we were looking for.” (GlaucoOrtolano). A scientist, for example, may discover something unexpectedly. Archimedes stepped into a bath and accidentally discovered the principle of buoyancy from the amount of water he displaced. Similarly Sir Isaac Newton is said to have accidentally discovered the theory of gravity by observing the falling apple while sitting under the apple tree.[4]

“Look for something, find something else, and realize that what you’ve found is more suited to your needs than what you thought you were looking for.” (Lawrence Block). One may be looking for something and find another unexpectedly or by unexpected means e.g. Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas while trying to reach India by travelling West and William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus while searching for comets.[5] Finally, one may accidentally find unexpected usage of some object or drug. Humphry Davy tested Nitrous oxide on himself and his friends as a laughing gas. To his surprise it acted as an anesthetic.[6] Osterloh et al. while evaluating Sildenafil citrate for the treatment of hypertension and angina accidentally realized that it induced erections in male test subjects.[7]

Serendipity and science

Serendipity has played a more important role in science than in any other field. Some of the most important scientific discoveries have occurred due to serendipity. The reason perhaps lies in the training imbibed by scientists whereby they can recognize an unexpected result as valuable and significant. Sir Alfred Nobel, for example, accidentally discovered dynamite while mixing nitroglycerine with silica.[8] Some interesting scientific discoveries where serendipity played an important role (other than those already mentioned) include the microwave oven, coca cola, corn flakes, teflon, vulcanized rubber, Bose-Einstein statistics, Velcro and helium. Each of these accidental discoveries has a background of interesting stories which are, however, not within the scope of this chronicle.

Serendipity in medical science

A host of important discoveries in medical science owe their origin to serendipity. Perhaps the most famous is the story of Sir Alexander Fleming and his discovery of Penicillin. Similarly, serendipity has paved the way for the usage of lithium as a psychotherapeutic drug, Nitrous oxide as an anesthetic, sildenafil as a drug for sexual dysfunction and saccharine and aspartame as sweetener.[9] Serendipity has also led to some remarkable consequences. In an interesting role reversal, Harold Varmus’ research works on breast cancer led to development of cellular oncogenes which play a role in brain development. Interestingly the reverse occurred with Robert Weinberg when his studies on rat brain tumor helped in understanding the etio-pathology of human breast cancer.[10]

Serendipity in Dermatology

As in other branches of science and medicine, dermatopharmacology has also enjoyed the fruits of serendipity in a major way. It has been responsible for major developments in the therapy of psoriasis and hair disorders as also in Dermatosurgery and Aesthetic Dermatology.

Serendipity in Psoriasis Therapy [Table 1]

Table 1.

Serendipity in psoriasis therapy

Dithranol

Dithranol has been derived from Goa powder extracted from the araroba tree which grew in the Bahia province in Brazil. It was imported from Brazil to India where it was used for centuries to treat ringworm. In 1876, a patient of Balmano Squire who had mistaken his psoriasis to be ringworm told him that he had used the powder to treat his “ringed” psoriasis and had got good results. Later, the active ingredient in the powder was identified as chrysarobin from which the first synthetic preparation, anthralin was derived. Anthralin was found to be an effective treatment for psoriasis by Galewsky in 1916.[11]

Vitamin D3 analogs

In 1985, Morimoto and Kumahara reported the case of an 81-year-old man who had osteoporosis along with extensive psoriasis. He was prescribed 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3, 0.75 mg/day orally. Though he was not receiving either topical or systemic treatments for psoriasis, the psoriatic lesions cleared in 2 months.[12] Subsequently they published an open study in the British Journal of Dermatology about the role of vitamin D3 on Psoriasis in both oral and topical forms.[13]

Methotrexate

Gubner et al. in 1951 observed remission of psoriasis in a patient of rheumatoid arthritis being treated with aminopterin, a drug closely related to methotrexate.[14] They followed this by using aminopterin in a study with 13 patients of psoriasis. All the patients showed good response to daily dose of oral aminopterin, although all of them developed side effects. Later, methotrexate, a more effective and less toxic folic acid antagonist than aminopterin, was used for the treatment of psoriasis using the same logic.[15]

Cyclosporine

Cyclosporin A (CSA), a drug with immunosuppressive properties was initially isolated from the fungus Tolypocladium inflatum, (Beauverianivea) obtained from a soil sample in 1969 from Hardangervidda, Norway by Dr. Hans Peter Frey, a Saandoz scientist.[16] Its immunosuppressive effects were discovered in 1972. Later, in a pilot study on effects of CSA in rheumatoid arthritis, four of the patients who also had psoriatic arthritis had almost total clearance of their psoriasis within a week of CSA orally. However, the psoriatic lesions gradually returned in all patients to their previous severity within 2 weeks after stopping CSA.

Chondroitin sulfate

Chondroitin sulfate, a natural glycosaminoglycan, is used for the treatment for osteoarthritis. Joseph Verges observed that patients with osteoarthritis with concomitant psoriasis experienced a marked improvement of their psoriatic plaques within a few days after treatment with chondroitin sulfate.[17] Though the drug has later been used for psoriasis the results have been variable.

Gemcitabine and cisplatin

Cagiano et al. in 2008 reported complete disappearance of psoriasis of fingernails and scalp of ten years’ duration in a 55 yearold male, 2 weeks after therapy of his lung metastasis with gemcitabine and cisplatin. There was no recurrence of the psoriasis even after 3 months of follow-up.[18]

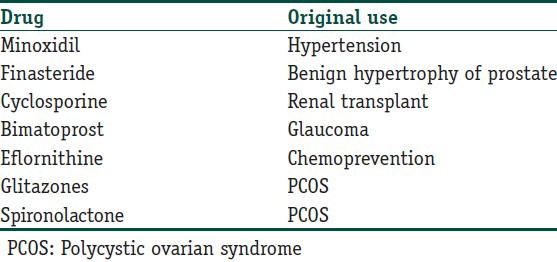

Serendipity in Hair Disorders [Table 2]

Table 2.

Serendipity in Hair Disorders

Several medications that affect human hair growth have been born out of serendipity. These include medications for hair loss as well as for hirsutism. While Minoxidil, Finasteride, Cyclosporine and Bimatoprost have been useful in different kinds of alopecia, Alphadifluoromethyl ornithine, Glitazones and Spironolactone have been used as hair-removers and in hirsutism.

Minoxidil

Minoxidil was originally used as an oral therapy for hypertension. It lowers blood pressure by acting as a nitric oxide agonist and potassium channel opener. In 1977, hypertrichosis was noted as a severe cosmetic problem in 5 female patients using this drug as an antihypertensive. The excessive hair was removed by calcium thioglycolate depilatory agent.[19] Subsequently reversal of alopecia was noted in patients with minoxidil.[20] In 1981 the drug was found to be of use in both alopecia areat[21] andandrogenetic alopecia.[22] Subsequently minoxidil became the first drug approved by US FDA for the treatment of alopecia and it has progressed to become one of the most widely used medications for hair restoration, especially androgenetic alopecia.

Finasteride

Finasteride is a 5-α-reductase type 2 isoenzyme inhibitor. The drug (5 mg per day) had FDA approval for benign hypertrophy of prostate since1992. It was accidentally discovered to grow hair on the bald scalp of men using this drug.[23] The drug was shown to reduce scalp dihydrotestosterone levels by about 69%.[24] Finasteride in the dosage of 1 mg per day was subsequently approved by US FDA for males with androgenetic alopecia in 1997.

Cyclosporine

Long-term use of cyclosporine was found to produce hirsutism in renal transplant patients.[25] It was postulated that Cyclosporine inhibits the activation of helper T cells which may be pathogenic in alopecia areata and probably prolongs the anagen phase also. Topical cyclosporine was then used in trials with nude mice grafted with human hair and it slowed down the shedding of hair. Human studies also showed good results.[26] But further studies with topical cyclosporine did not produce encouraging results in male pattern alopecia. Oral cyclosporine has also been tried in alopecia areata in small studies. Cosmetically acceptable terminal hair regrowth on the scalp occurred in 50% patients but within 3 months of discontinuation of cyclosporine, significant hair loss occurred again.[27]

Bimatoprost

Prostaglandin analogs are used in glaucoma to reduce intraocular pressure. Latanoprost, travopost and bimatoprost have been widely used as eye drops. Serendipitously, these medications, when used for glaucoma, were found to stimulate eyelash growth and pigmentation.[28] There appears to be an increase in anagen follicles, resulting in thicker, darker, and longer eyelashes. Since 2008, bitanoprost has US FDA approval for use in cosmetic enhancement of eyelashes. However, the clinical results of prostaglandin analogues in other forms of alopecia have shown conflicting results.[29]

Eflornithine

Takigawa et al. accidentally discovered that mice shed hair when treated with an ornithine decarboxylase inhibitor called alpha difluoromethyl ornithine (DFMO), a chemoprevention agent.[30] Later studies showed that ornithine decarboxylase, though plentiful in the anagen follicular bulbs, was scarce in the telogen and catagen stages. This finding led to the development of a topical eflornithine hydrochloride cream that was found to remove unwanted hair in hirsute women.[31]

Glitazones

Glitazones or thiazolidinediones (TZD) increase tissue insulin sensitivity by interacting with peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor y (PPARy) to increase insulin sensitivity and are used as antidiabetic agents. Abnormal glucose metabolism is a part of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). It was observed that when Pioglitazone, a TZD was used in PCOS, there was an improvement in the hirsutism.[32] Pioglitazone has also been tried in psoriasis[33] and Lichen Planopilaris[34] as an PPARγ agonist.

Spironolactone

Spironolactone is a potassium sparing diuretic that was used as an antihypertensive drug. It was seen to improve hirsutism in a woman with concomitant polycystic ovarian disease. It was found to interfere with androgen-related hair growth. Hence, it has been subsequently used as an off-label drug for hirsutism.[35]

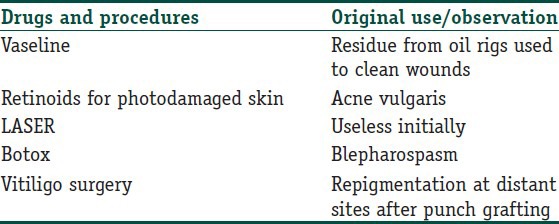

Serendipity in Aesthetic Dermatology [Table 3]

Table 3.

Serendipity in aesthetic dermatology

Vaseline

Vaseline was accidentally discovered by Robert Chesebrough in 1859. On a visit to the oil fields in Titusville, Pennsylvania he found that the workers were using a residue from oil rig pumps to heal wounds, cuts and burns. This residue was known as rod wax. Back in Brroklyn, Chesebrough extracted the petroleum jelly from the rod wax. He named the product Vaseline.[36]

Retinoids for photodamaged skin

Retinoids were first introduced for the treatment of acne vulgaris in the 1959.[37] In the mid- 1980s Kligman et al. observed serendipitously that topical tretinoin used on the face was also capable of reversing the sunlight-induced damage to the skin and partially decelerating the rate of photoaging.[38]

Lasers

Charles Townes and Arthur Schwalow discovered the MASER in 1954 and later the LASER in 1958.[39] Ironically, at the time of discovery Charles Townes had no idea about its applications and was even teased by his colleagues about the irrelevance of his discovery. Though this discovery fetched him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1964, he did not proceed any further with research on the subject. A tool made for a given purpose (actually no real purpose) then found applications after its discovery. This useful invention was actually a ‘use’less application at the time of its discovery. The usefulness of LASERS in various aspects of science including Medicine and Dermatology was explored after its discovery. Pioneering work on the use of LASERs in Dermatology was done by Leon Goldman of Cincinnati about a decade after its discovery.[40]

Botox

The discovery of the use of Botox as a tool of aesthetic Dermatology is a unique tale of marital partnership applied for the benefit of science. In 1987, a patient suffering from blepharospasm was being treated with Botox by Dr. Jean Carruthers, a Canadian ophthalmologist. The patient was being administered small amounts to reduce the spasm. The patient noted that with every injection of Botox, the wrinkles on the forehead between her eyebrows seemed to be disappearing. The patient was happy that she was looking younger. Coincidentally Dr Carruther's husband, Dr. Alistair Carruther was a Dermatologist. The wife narrated the fascinating story of her patient's wrinkles to her husband over dinner. To further convince her husband she injected Botox into the skin of their receptionist Cathy Bickerton. The resultant disappearance of wrinkles convinced Alistair. However, other patients refused to get themselves injected with Botox, and to convince them Jean injected it into her own face.[41]

Vitiligo surgery

Surgical treatment of vitiligo can be done by autologous punch grafting. Interestingly, apart from repigmentation at the grafted sites spontaneous repigmentation has also been observed in patches other than the grafted site after autologous punch grafting.[42] Other interesting phenomena noted by some workers have been the simultaneous repigmentation at donor sites with depigmentation of grafts at recipient site, donor site depigmentation after complete repigmentation of grafted site and repigmentation at grafted sites after failure on previous attempts.[43]

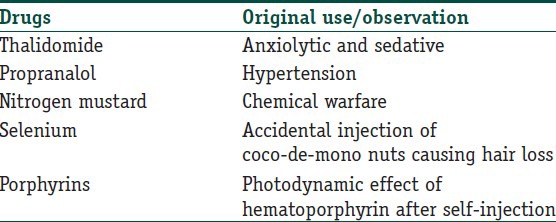

Miscellaneous [Table 4]

Table 4.

Serendipity in miscellaneous conditions

Thalidomide

Thalidomide was first used as a drug to cure anxiety and tension in Germany in 1957. It was also found to reduce the symptoms of morning sickness and was therefore prescribed to pregnant women [Table 4]. Shortly thereafter it was noted that a large number of children born of pregnant mothers taking Thalidomide developed a limb deformity known as Phaecomalia. Subsequently the drug was withdrawn from the market.[44] In 1964, Sheskin, an Israeli dermatologist, was treating a male patient of Erythema nodosum leprosum, who was in acute pain and hence could not sleep. Sheskin had a few tablets of Thalidomide in his possession and gave them to his patient. The patient could not only sleep well but also his lesions improved considerably after taking Thalidomide.[45] Since then thalidomide, a banned drug due to its teratogenicity, has found a significant place in the treatment of leprosy.[46]

Propranalol

Propranolol, a β blocker, is generally used for hypertension [Table 4]. It was serendipitously found to improve the nasal hemangioma in an infant when administered for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.[47] Recently, it has replaced corticosteroids as a therapy for this condition.

Nitrogen mustard

Nitrogen mustards are nonspecific DNA- alkylating agents used in chemical warfare [Table 4]. During World War 2, nitrogen mustards were being investigated at Yale University and were found to deplete lymphocyte counts in blood. In 1942, the first human trials of its use in lymphoma were conducted and it became the first chemotherapeutic drug, mustine.[48]

Selenium

In Brazil and Venezuela, coco-de-mono trees bear nuts that are known to be lethal for monkeys [Table 4]. Inadvertent human consumption led to loss of hair in addition to tremors. In 1965, Francisco Kerdel-Vegas, a professor of Dermatology in Venezuela, isolated the active principle in the nut and identified it as the selenium analog of the sulfur amino acid cystathionine.[30] This agent has been subsequently used in trichology for its depilatory effects.

Porphyrins

Porphyrins are a group of chemicals that help form many important substances in the body, including hemoglobin [Table 4]. Additionally, they can absorb energy from photons and the energy is then passed on. In 1913 Friedrich Mayer-Betz injected hematoporphyrins into his body and exposed himself to sunlight to examine its photodynamic effects. He developed an intense swelling of face and body and the reaction subsided only after a few months.[49] This observation led to a series of experiments and in 1960, Schwartz and Lipson isolated an active ingredient called hematoporphyrin derivative. Later Mayer-Betz's original observation was utilized to extensively use porphyrins and their derivatives in photodynamic therapy for psoriasis, acne, skin cancer, vitiligo, warts and alopecia areata.[50]

Conclusion

The phenomenon of serendipity has played a tremendously beneficial role in science, especially medical science. Dermatology as a speciality has also widely benefitted from these ‘happy accidents’. As time progresses many more such serendipitous drugs are expected to be discovered. These new drugs may not only strengthen the existing armamentarium of already available medications, but also find cures for some hitherto incurable skin ailments.

What is new?

Compilation of serendipity-mediated drug indications which may prove to be useful for future chroniclers of Dermatology.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Definition of serendipity in English. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/serendipity .

- 2.Serendipity. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serendipity .

- 3.Van Andel P. Anatomy of the unsought finding. Serendipity: Orgin, history, domains, traditions, appearances, patterns and programmability. Brit J Phil Sci. 1994;45:631–48. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serendipity in science. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.northcoastjournal.com/humboldt/serendipity-in-science/Content oid=2131243 .

- 5.William Hershel discovers Uranus – History channel. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/william-hershel-discovers-uranus .

- 6.Davy, Humphry - Meedical discoveries. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.discoveriesinmedicine.com/General-Information-and-Biographies/Davy-Humphry.html .

- 7.Morales A, Gingell C, Collins M, Wicker PA, Osterloh IH. Clinical safety of oral Sildenafil citrate (VIAGRA) in the treatment of erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1998;10:69–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3900354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfred Nobel and the history of dynamite. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.nobelprize.org/alfred_nobel/biographical/articles/lperhaps lies in the inherent training of life-work/nitrodyn.html .

- 9.Ban TA. The role of serendipity in drug discovery. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2006;8:335–44. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2006.8.3/tban. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandra G. Serendipity in modern medical brreakthroughs. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.drgauravchandra.blogspot.in/2011/03/serendipity-in-modern-medical.html .

- 11.Steger JW, Hollander A. Anthralin and chrysarobin: A reexamination of the origins and early use. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:625–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morimoto S, Kumahara Y. A patient with psoriasis cured by 1 alpha-hydroxyvitamin D3. Med J Osaka Univ. 1985;35:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morimoto S, Yoshikawa K, Kozuka T, Kitano Y, Imanaka S, Fukuo K, et al. An open study of vitamin D3 treatment in psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:421–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1986.tb06236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gubner R, August S, Ginsberg V. Therapeutic suppression of tissue reactivity. II. Effect of aminopterin in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis. Am J Med Sci. 1951;221:176–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter GA. The use of methotrexate in the treatment of psoriasis. Aust J Dermatol. 1962;6:248–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1962.tb01651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Svarstad H, Bugge HC, Dhillion SS. From Norway to Novartis: Cyclosporin from tolypocladium inflatum in an open access bioprospecting regime. Biodivers Conserv. 2000;9:1521–41. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vergés J, Montell E, Herrero M, Perna C, Cuevas J, Pérez M, et al. Clinical and histopathological improvement of psoriasis with oral chondroitin sulfate: A serendipitous finding. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cagiano R, Bera I, Vermesan D, Flace P, Sabatini R, Bottalico L, et al. Psoriasis disappearance after the first phase of an oncologic treatment: A serendipity case report. Clin Ter. 2008;159:421–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earhart RN, Ball J, Nuss DD, Aeling JL. Minoxidil induced hypertrichosis: Treatment with calcium thioglycolate depilatory. South Med J. 1977;70:442–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zappacosta AR. Reversal of baldness in patient receiving minoxidil for hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1480–1. doi: 10.1056/nejm198012183032516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weiss VC, West DP, Mueller CE. Topical minoxidil in alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;5:224–6. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(81)80077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seidman M, Westfried M, Maxey R, Rao TK, Friedman EA. Reversal of male pattern baldness by minoxidil. A case report. Cutis. 1981;28:551–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diani AR, Mulholland MJ, Shull KL, Kubicek MF, Johnson GA, Schostarez HJ, et al. Hair growth effects of oral administration of finasteride, a steroid 5 alpha-reductase inhibitor, alone and in combination with topical minoxidil in the balding stumptail macaque. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:345–50. doi: 10.1210/jcem.74.2.1309834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drake L, Hordinsky M, Fiedler V, Swinehart J, Unger WP, Cotterill PC, et al. The effects of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:550–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett WM, Serra J, Fischer S, Norman DJ, Barry JM. Cyclosporine in renal transplantation with hirsutism. Am J Kidney Dis. 1985;5:214. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(85)80054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gilhar A, Pillar T, Etzioni A. Topical cyclosporine in male pattern alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:251–3. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70033-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta AK, Ellis CN, Cooper KD, Nickoloff BJ, Ho VC, Chan LS, et al. Oral cyclosporine for the treatment of alopecia areata. A clinical and immunohistochemical analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:242–50. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(90)70032-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centofanti M, Oddone F, Chimenti S, Tanga L, Citarella L, Manni G. Prevention of dermatologic side effects of bimatoprost 0.03% topical therapy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142:1059–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen JL. Enhancing the growth of natural eyelashes: The mechanism of bimatoprost-induced eyelash growth. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:1361–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yesudian P. Serendipity in trichology. Int J Trichology. 2011;3:1–2. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.82116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hennemann A. Eflornithine for hair removal. Topical application for hirsutism. Med Monatsschr Pharm. 2001;24:38–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romualdi D, Guido M, Clampelli M, Giuliani M, Leoni F, Perri C, et al. Selective effects of pioglitazone on insulin and androgen abnormalities in normo- and hyperinsulinaemic obese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1210–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shafiq N, Malhotra S, Pandhi P, Gupta M, Kumar B, Sandhu K. Pilot trial: Pioglitazone versus placebo in patients with plaque psoriasis (the P6) Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:328–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baibergenova A, Walsh S. Use of pioglitazone in patients with lichen planopilaris. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012;16:97–100. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.11008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salavastru CM, Fritz K, Tiplica GS. Spironolactone in dermatological treatment. On and off label indications. Hautarzt. 2013;64:762–7. doi: 10.1007/s00105-013-2597-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schwager E. From petroleum jelly to riches. Drug News Perspect. 1998;11:127–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenkranzer R. Experiences with vitamins A and E in the treatment of serious forms of acne. Ther Ggw. 1959;98:197–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kligman AM, Grove GL, Hirose R, Leyden JJ. Topical tretinoin for photoaged skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:836–59. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(86)70242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Townes C. From the maser to the laser. Interview by Joerg Heber. Nat Mater. 2010;9:371–2. doi: 10.1038/nmat2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldman L, Rockwell RJ, Meyer R, Otten R, Wilson RG, Kitzmiller KW. Laser treatment of tattoos. A preliminary survey of three year's clinical experience. JAMA. 1967;201:841–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carruthers JD, Carruthers JA. Treatment of glabellar frown lines with C. botulinum-A exotoxin. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1992;18:17–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1992.tb03295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malakar S. Spontaneous repigmentation of vitiligo patches other than the grafted site. Indian J Dermatol. 1997;42:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lahiri K, Malakar S. The concept of stability of Vitiligo: A reappraisal. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:83–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.94271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim JH, Scialli AR. Thalidomide: The tragedy of birth defects and the effective treatment of disease. Toxicol Sci. 2011;122:1–6. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheskin J. Thalidomide in the treatment of lepra reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1965;6:303–6. doi: 10.1002/cpt196563303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Waters MF. An internally-controlled double blind trial of thalidomide in severe erythema nodosum leprosum. Lepr Rev. 1971;42:26–42. doi: 10.5935/0305-7518.19710004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Léauté-Labrèze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, Boralevi F, Thambo JB, Taïeb A. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2649–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc0708819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gilman A. The initial clinical trial of nitrogen mustard. Am J Surg. 1963;105:574–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(63)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.American Porphyria Foundation. History of porphyria. [Last accessed on 2014 Mar 19]. Available from: http://www.porphyriafoundation.com/about-porphyria/history-of-porphyria .

- 50.Pushpan SK, Venkatraman S, Anand VG, Sankar J, Parmeswaran D, Ganesan S, et al. Porphyrins in photodynamic therapy-a search for ideal photosensitizers. Curr Med Chem Anticancer Agents. 2002;2:187–207. doi: 10.2174/1568011023354137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]