Abstract

Background:

Vitiligo is an acquired discoloration of skin and mucous membrane of great cosmetic importance affecting 1-4% of the world's population. It causes disfiguration in all races, more so in dark-skinned people because of strong contrast. Men, women, and children with vitiligo face severe psychological and social disadvantage.

Aim:

To assess the impact of the disease on the quality of life of patients suffering from vitiligo, also to ascertain any psychological morbidity like depression associated with the disease and to compare the results with that of healthy control group.

Materials and Methods:

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD) are administered to 100 vitiligo patients presenting to the Dermatology OPD and 50 age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Results were analyzed and compared with that of control group. Findings are also correlated in relation to demographic and clinical profile of the disease. Statistical analysis is made to see the significance.

Results:

Vitiligo-affected patients had significantly elevated total DLQI scores (P < 0.001) compared to healthy controls. There is increase in parameters like itch, embarrassment, social and leisure activities in the patient cohort than the control group. Patients of vitiligo are also found to be more depressed (P < 0.001) than the controls.

Conclusion:

Quality of life (QOL) in patients affected with vitiligo declined more severely, and also there is increase in incidence of depression than in the control group. These changes are critical for the psychosocial life of the affected people.

Keywords: Depression, DLQI, HAMD, vitiligo

What was known?

Vitiligo was regarded as a harmless cosmetic skin disease.

Various studies show impairment if QOL and depression in Vitiligo patients

Vitiligo influences the social and psychological well being of patients.

Introduction

Vitiligo, considered just a cosmetic problem, affects a person's emotional and psychological well-being,[1,2] having major consequences on patient's life.[3] Most of the patients of vitiligo report embarrassment and low self-esteem leading to emotional stress and social isolation, particularly if the disease develops on exposed areas of the body. The sense of being stigmatized may affect a person's interpersonal and social behavior, which in turn increases the risk of depression and other psychosocial disorders.[4,5,6,7] Although not fatal, it may considerably influence patients’ health-related quality of life (QOL) and psychological well-being.[8]

There are a lot of studies assessing the QOL in vitiligo patients in India and abroad. There are also various studies assessing depression associated with vitiligo. As there is a paucity of case control studies comparing the incidence and degree of impairment in QOL as well as assessment of depression in the same group of patients, this study was undertaken with the following aims and objectives.

To assess quality of life in patients of vitiligo and to compare with that of matched control population.

To compare the frequency and the level of depression in patients of vitiligo with that of matched control population.

To analyze and compare the values of DLQI and level of depression with the clinico-demographic pattern of vitiligo.

Materials and Methods

This is a cross sectional study, descriptive, case control, hospital-based study conducted in the Dermatology and Venereology OPD of a tertiary care teaching hospital from 1/6/2011 to 31/5/2012.

Clinically diagnosed vitiligo patients in the age group of 18 to 40 willing to take part in the study were included. Patients with personal and familial mental illness, substance abuse, and other obvious causes of depression were excluded. Control group included age-matched healthy medical and paramedical workers. They had minor skin changes like freckles, grade 1 acne, wrinkles, tanning and a few cases of dermatophytosis and dark complexion. Detailed demographic variables, age of onset, duration and course of the disease, family and treatment history were recorded. Clinical examination in respect to skin type, type of vitiligo, site of involvement, extent, and percentage of involvement was done.

English language versions of the DLQI and HAMD-17 questionnaire were translated into Assamese language by two bilinguals. Forward translation and backward translation was done by different translator (two bilinguals each) and validated by three members.

Patients and controls were given the DLQI questionnaire at the first visit after informed consent. QOL assessment was done using Dermatology Life Quality Index introduced by Prof A Y Finlay. It is a valid questionnaire including 10 items on patient's symptoms, feelings, routine activities, kind of clothes, social or leisure activities, physical exercise, educational activities, sexual activities, interpersonal relationships, and treatment options with 0-30 points score.[9] The severity of the DLQI was grouped into 5 groups [Table 1]. Responses on the DLQI were recorded and compared with that of the control population.

Table 1.

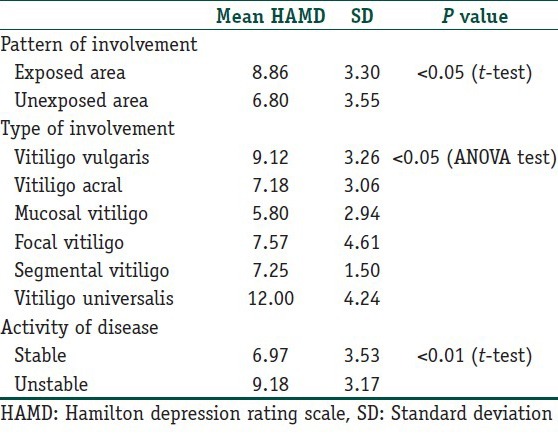

Mean HAMD Scores according to the pattern, type and activity of vitiligo

HAMD 17 questionnaire is used to find out the level of depression in vitiligo patients and to compare with that of the control group. To avoid overburdening of the patient, HAMD-17 was administered at the second visit.

Statistical analysis

Analysis of data was performed with the aid of SPSS version 11.5. Descriptive statistics, mean and SD were calculated. Comparison of parametric variables done by Student's t-test and ANOVA test. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant and further chi square test (χ2) is applied.

Results

One-hundred vitiligo patients of age range 18-40 and 50 ages-matched healthy controls participated in the study. The mean age of the patients was 29.72 ± 7.01 years. Fifty-nine females and fourty-one males constituted the study group with female to male ratio of 1.44:1.

Patients were grouped into married, unmarried, and widows constituting 49%, 48%, and 3%, respectively. Mean duration of the disease was 4.60 ± 5.90 years. The most common variety observed was vitiligo vulgaris (66%), followed by acro-facial (11%), mucosal (10%), focal (7%), segmental (4%), and universalis (2%). Seventy-nine percent of patients had more than 10% body surface area involvement, 80% had involvement of exposed areas, and 67% had an actively progressive disease.

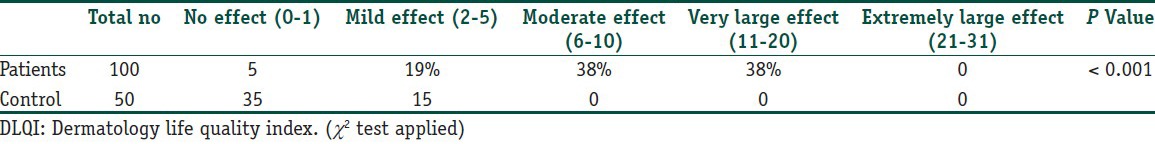

In this study, 95% of the patients had elevated DLQI with very large, moderate, and mild effect in 38%, 38%, and 19% of patients, respectively, while 30% of control population showed mild effect (P < 0.001) [Table 2]. The DLQI score ranged from 1-20 with mean DLQI score of 9.08 ± 4.46 in patient and 1.04 ± 1.12 in control group (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

DLQI grading with scores for patients and control

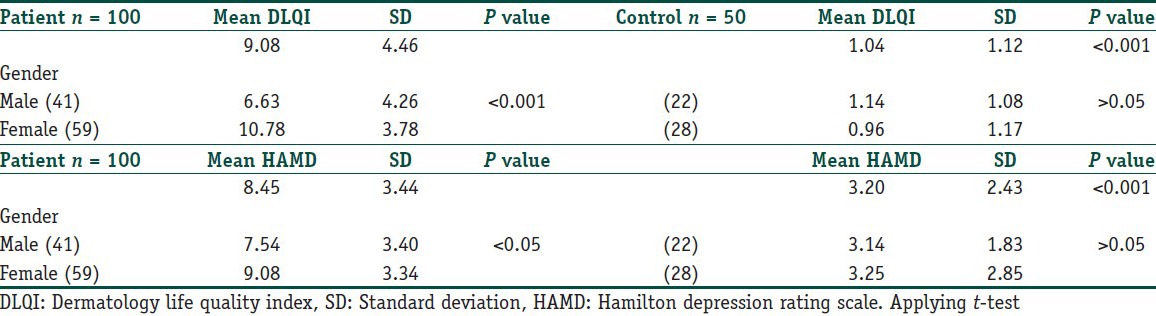

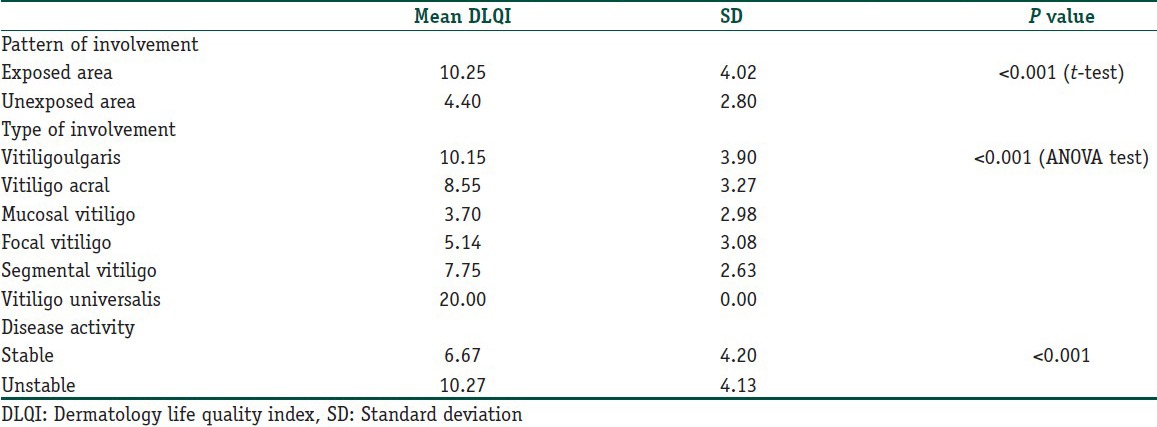

Females had higher mean DLQI scores (10.78 ± 3.78) than males (6.63 ± 4.26) with a statistical significance (P < 0.001) [Table 3]. High mean DLQI score were found in vitiligo vulgaris (10.15 ± 3.90), unstable vitiligo (10.27 ± 4.13), and those with lesions on exposed parts (10.25 ± 4.02). Highest mean DLQI score was seen in vitiligo universalis (20.00 ± 0.00) [Table 4]. All these values had statistical significance (P < 0.001).

Table 3.

DLQI and HAMD Scores for vitiligo patients and controls

Table 4.

Mean DLQI Scores according to the pattern, type and activity of vitiligo

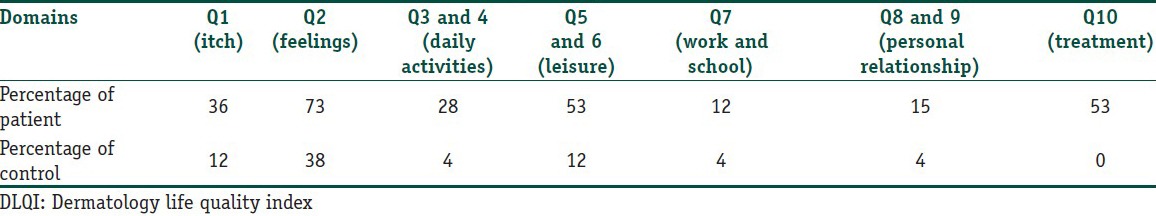

The item analysis of the questionnaire revealed the highest effects of the disease on QOL for feelings (item 2), treatment-related (item 10), and social and leisure activities (item 5 and 6) [Table 5].

Table 5.

Item analysis of questionnaires of DLQI

Fifty-nine percent patients were found to be depressed, out of which 53% had mild and 6% had moderate depression while none had severe depression. In the control group, only 6% had mild depression and none had moderate or severe depression.

The mean HAMD score was 8.45 ± 3.44 and 3.20 in cases and controls, respectively, which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). [Table 3] We found high mean depression scores in females (P < 0.05), married patients (P < 0.05), vitiligo vulgaris (P < 0.05), in those with skin lesions on exposed parts of the body (P < 0.05), and in unstable vitiligo (P < 0.01). Highest HAMD score was found in vitiligo universalis with a mean of 12.00 ± 4.24 [Table 1]. Eight percent of patients had suicidal ideations (Q3) with no case of suicidal attempts, whereas no control had either suicidal ideations or attempts. In our study, 89% cases and 38% controls had difficulty in initiation of sleep (Q4).

Discussion

Vitiligo lowers individual's quality of life by unfavorably influencing social relations, work, games and sports affecting overall social life due to disfigurement.[10] The psychological impact can have serious implications in dark skin, due to noticeable contrast.[11]

We included 100 vitiligo patients and 50 age-matched healthy controls with an age range of 18-40 years. This age group was specifically selected to avoid age-related influence in QOL and psychological evaluation.[12,13]

In this study, 95% of patient had elevated DLQI against 30% in control group. The mean DLQI was elevated in the patient group with a score of 9.08 ± 4.46 as compared to a very low score of 1.04 ± 1.12 in control group, which is of high statistical significance (P < 0.001).

Seventy-six percent of patients had high DLQI scores falling into very large (38%) and moderate effect group (38%), whereas not a single control had large or moderate DLQI score indicating considerable effect of vitiligo on QOL of patient (P < 0.001).

In our study, we found a higher mean DLQI scores in females with a statistical significance of P < 0.001, which correlates with other studies,[14,15,16,17] whereas some studies observed no relationship between gender and quality of life.[18,19] The higher DLQI score in female patients is probably due to the greater social consequences in women.

We found higher DLQI score in married females than in married males (P < 0.001), which could be due to the discrimination faced by females from the spouses and in-laws in Indian scenario. Even legal issues have been reported in a study from Iran.[20] Another study from Iran reported significant higher scores of DLQI in married women than in single women (P =0.001).[18]

High mean DLQI score (10.27 ± 4.13) in patients with unstable vitiligo and those with lesions on exposed parts (10.25 ± 4.02) (P < 0.001) was in agreement with various studies,[21,22] whereas some studies have not observed any correlation.[14,18]

Highest mean DLQI score (20.00 ± 0.00) was seen in vitiligo universalis when compared to localized vitiligo with statistical significance (P < 0.001). Similar observation was reported from Saudi Arabia.[23] Thus, we observed that high DLQI score is associated with high disease activity, increase body surface involvement, and lesions on exposed part of the body. All of these can add to the disease-related stress, influencing a patient's response to the therapy adversely. An Indian study reported better response to therapy in patients with low DLQI scores.[19]

In our study, 59% of patients were depressed, which was similar to some studies stating depression in 69% and 46.2% cases.[22,23] However, few studies have found lower prevalence of psychological morbidity of 33.63%, 15%, and 10% using different assessment tools like Psychiatric Assessment Schedule (PAS) and General Health Questionnaire (GHQ).[4,5,24] The use of different diagnostic tools may be the cause of the difference in the grading. Ninety-four percent in the control group had no depression while 6% had mild depression with a mean score of 3.20 as against 8.45 in patients with a high statistical significance (P < 0.001).

In our study, the frequency of depression is influenced by activity, extent, and distribution of the disease. High HAMD score of 12.00 ± 4.24 was found in two patients of vitiligo universalis, and 6 of our patients with high activity had suicidal ideations while none of the control group had such ideas. High mean HAMD scores in married female patients with active disease on the exposed parts of the body as noted in our study resembles the observation by Marwah salah et al., contrary to that by Maleki et al. who observed no such correlation.[23,25] The difference in the prevalence of depression in different studies could be due to the different social, behavioral, and cultural factors along with difference in population characters and assessment tool used. The present study showed that depression in vitiligo patients is related to the presence of lesions in a visible area leading to poor body image and compromised self-esteem along with unstable nature of the disease resulting in doubts and uncertainty regarding prognosis.

Conclusion

Our study showed major impairments in QOL and higher prevalence of depression in patients with vitiligo, especially in those with high disease activity, increase body surface involvement, and lesions on exposed part of the body. Fifty-nine percent patients suffered from depression, which cannot be taken as coincidence. The chronic nature of the disease, long-term treatment, lack of uniform effective therapy, and unpredictable prognosis of the disease and therapy causes psychological burden contributing to compromised QOL as well as depression in some patients. As the extent and the activity of the disease are directly proportional to the DLQI scores, we conclude that DLQI may be used as a prognostic tool. This study stresses the importance of counseling and assurance along with treatment, which may reduce the disease-related anxiety and stress enhancing the efficacy of therapy.

What is new?

This is the first case control study observing statistically significant impairment of QOL in comparison to control from North East India.

Statistically significant impaired QOL as well as frequency and severity of depression noted in the same group of patients.

The impairment of QOL as well as the severity of depression were directly proportional to the surface area and activity of the disease.

Wide spread Vitiligo vulgaris, especially on exposed areas and Vitiligo universalis had high DLQI and HAMD score.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to our patients and their attendants, faculties and residents, nursing staff and paramedical workers of Department of Dermatology for their cooperation in various aspects of this work.

We acknowledge Dr. A. Saikia for statistical evaluation, Mr. D. Pathak and Mrs. A. Nath for forward translation and Mrs. Binita Choudhury and Mr. P. Narzery for backward translation of DLQI And HAMD-17. We also acknowledge three member Prof. D. Hazarika, Prof. D. Bhagawati and Asst. Prof. C. Patowary for validation.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Ongenae K, Beelaert L, van Geel N, Naeyaert JM. Psychosocial effects of vitiligo. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hautmann G, Panconesi E. Vitiligo: A psychologically influenced and influencing disease. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:879–90. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(97)00129-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Firooz A, Bouzari N, Fallah N, Ghazisaidi B, Firoozabadi MR, Dowlati Y. What patients with vitiligo believe about their condition. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:811–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattoo SK, Handa S, Kaur I, Gupta N, Malhotra R. Psychiatric morbidity in vitiligo: Prevalence and correlates in India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:573–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahmed I, Ahmed S, Nasreen S. Frequency and pattern of psychiatric disorders in patients with vitiligo. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2007;19:19–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimes PE. White patches and bruised souls: Advances in the pathogenesis and treatment of vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(Suppl):S5–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaturvedi SK, Singh G, Gupta N. Stigma experience in skin disorders: An Indian perspective. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:635–42. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radtke MA, Schäfer I, Gajur A, Langenbruch A, Augustin M. Willingness-to-pay and quality of life in patients with vitiligo. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161:134–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Finlay AY, Khan GK. [Last accessed on 2012 Sep 10]. Available from: http://www.dermatology.org.uk .

- 10.Bilgiç O, Bilgiç A, Akiş HK, Eskioğlu F, Kiliç EZ. Depression, anxiety, and health related quality of life in children and adolescents with vitiligo. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:360–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kent G, Al-abadie M. Factors affecting responses on dermatology life quality index among vitiligo sufferers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:330–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Son SE, Kirchner JT. Depression in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:2297–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh A, Misra N. Loneliness, depression and sociability in old age. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:51–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mashayekhi V, Javidi Z, Kiafar B, Manteghi AA, Saadatian V, Esmaeili HA, et al. Quality of life in patients with vitiligo: A descriptive study on 83 patients attending a PUVA therapy unit in Imam Reza Hospital, Mashad. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:592. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.69097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hanan M Saleh, Samar Abdallah M Salem, Rania S El-Sheshetawy, Afaf M Abd El-Samei. Comparative Study of Psychiatric Morbidity and Quality of Life in Psoriasis Vitiligo and Alopecia Areata. Egypt Dermatol Online J. 2008;4:2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Özlem Devrim Balaban, Murat İlhan Atagün, Halise Devrimci Özgüven, Hüseyin Hamdi Özsan. Psychiatric Morbidity in patients with Vitiligo. J Psychiatry Neurol Sci. 2011;24:306–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zahida Rani, Muhammad Saleem Khan, Shahbaz Aman, Muhammad Nadeem, Abdul Hameed, Atif Hasnain Kazmi, et al. Quality of Life Issues and new beach marks in the assessment of skin diseases. Br J Dermatol. 1975;72:395–400. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolatshahi M, Ghazi P, Feizy V, Hemami MR. Life quality assessment among patients with vitiligo: Comparison of married and single patients in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:700. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsad D, Pandhi R, Dogra S, Kanwar AJ, Kumar B. Dermatology Life Quality Index score in vitiligo and its impact on the treatment outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:373–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05097_9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ashrafian M. 5th ed. Tehran: Teimourzadeh Publication; 2001. Essentials of forensic medicine; pp. 51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soodabeh Zandi, Saeideh Farajzadeh, Narjes Saberi. Effect of Vitiligo on self reported quality of life in Southern part of Iran. J Pak Assoc Dermatol. 2010;21:4–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ongenae K, Van Geel N, De Schepper S, Naeyaert JM. Effect of Vitiligo on self reported health-related quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2005;152:1165–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Al Robaee AA. Assessment of quality of life in Saudi patients with vitiligo in a medical school in Qassim province, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1414–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esfandiar Pour I, Afshar Zadeh P. Frequency of depression in patients suffering from Vitiligo. Iran J Dermatol. 2003;6:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maleki M, Avidi Z, Kiafar B, Saadatian V, Saremi AK. Prevalence of depression in vitiligo patients. Q J Fundament Ment Health. 2005;7:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma N, Koranne RV, Singh RK. Psychiatric Morbidity in Psoriasis and Vitiligo: A comparative study. J Dermatol. 2001;28:419–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2001.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Salah ElDin Zaki M, Elbatrawy AN. Catecholamine level and its relation to anxiety and depression in patients with Vitiligo. J Egypt Women Dermatol Soc. 2009;6:74–9. [Google Scholar]