Abstract

Neonatal pustular eruption is a group of disorders characterized by various forms of pustulosis seen in first 4 weeks of life. Its presentation is often similar with some subtle differences, which can be further established by few simple laboratory aids, to arrive at a definite diagnosis. Given their ubiquitous presentation, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate among self-limiting, noninfectious, pustular dermatosis such as erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, miliaria pustulosa, etc., and potentially life threatening infections such as herpes simplex virus and varicella zoster virus infections. This review article tries to address the chronological, clinical, morphological, and histological differences among the various pustular eruptions in a newborn, in order to make it easier for a practicing dermatologist to diagnose and treat these similar looking but different entities of pustulation with a clear demarcation between the physiological benign pustular rashes and the infectious pustular lesions.

Keywords: Erythema toxicum neonatorum, neonatal pustular eruption, pustulosis

What was known?

There are a number of neonatal pustular dermatoses, benign and self-limiting as well as infectious and potentially life-threatening, which can present with similar-looking symptoms and clinical signs and it is important to differentiate between them so as to facilitate early diagnosis and management

Introduction

Diagnosis of pustular eruption in the first month of life of a newborn can be puzzling. It is usually based on clinical features, aided by few simple lab investigations. The practical issue posed by pustular eruptions in neonates relates to the process of ruling out infections. It is important to be able to distinguish among the benign physiological rashes and the more clinically significant pathological pustular eruptions. Though most transient pustular eruptions observed after birth are sterile and self-limiting, those with infectious origin deserve prompt diagnosis and treatment in order to avoid an adverse outcome.

Pustular dermatosis of neonate can be divided into the following

- Noninfectious pustular eruptions

- Erythema toxicum neonatorum

- Transient pustular melanosis

- Miliaria pustulosa

- Infantile acropustulosis

- Eosinophilic pustulosis

- Acne neonatorum

- Benign neonatal cephalic pustulosis

- Pustular psoriasis

- Pustular eruption of Transient myeloproliferative disorder.

-

Infectious pustular eruptions

- Bacterial: Impetigo, folliculitis, congenital syphilis, listeriosis (rare), and secondary bacterial infection of any primary dermatosis

- Viral: Herpes simplex virus infection, and varicella

- Fungal: Cutaneous candidiasis (congenital and neonatal), malassezia pustulosis.

Transient benign pustular eruptions

Erythema toxicum neonatorum

(synonyms: Erythema neonatorum allergicum, and toxic erythema), the terminology is a misnomer as there is no evidence of any toxic cause. It is the most common transient rash in healthy neonate, which is a benign, self-limiting, physiological rash affecting about 50% of term newborn. It is rarely seen in preterm infants. They usually begin at 1 to 2 days of age, but may occur at any time until about the fourth day.[1,2,3] Blotchy erythematous macules 1 to 3 cm in diameter with a 1 to 4 mm central vesicle or pustule are seen in erythema toxicum neonatorum (ETN). Number of lesions can vary from one or two to several hundred. They are not only more profuse on the trunk, but also commonly appear on face and proximal limbs and spares palms and soles. The infant appears well, unperturbed by the eruption. Spontaneous recovery usually occurs within 3 to 7 days without any residual pigmentation[3] [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

A neonate with multiple discrete tiny pustules on erythematous base, distributed over the trunk

A smear of the central vesicle or pustule contents reveals numerous eosinophils on Wright stain preparations. No organisms can be seen or cultured. A peripheral blood eosinophilia of up to 20% may be associated with severe cases.[4]

No treatment is indicated. Apprehensive parents can be reassured about the benign nature of the eruption.

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis

Transient neonatal pustular melanosis (TNPM) is an idiopathic pustular eruption that heals with brown pigmented macules. TNPM is more common in black neonates, and is probably the reason for the so-called lentigines neonatorum noted in 15% of black newborns.[5] The lesions are almost invariably present at birth with 1–3 mm, flaccid, superficial, fragile pustules with no surrounding erythema. Usually distributed over chin, neck, forehead, back, and buttocks, even palms and soles may be involved. Eventually the pustules rupture and form brown crust and finally a small collarette of scales. Sometimes pigmented macules are already present at birth. The pigmentation may persist for about 3 months but the affected neonates are otherwise entirely normal.[6,7] It has been suggested that it is merely a variant of ETN and their description has been separated for the sake of clarity[6] [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

A neonate with numerous discrete tiny pustules with hyperpigmented background, distributed over forehead, limbs, and trunk

Smear from pustules content reveals predominance of neutrophils with occasional eosinophils on Wright stain preparation.[8] Bacterial culture is negative. On histopathology pustular lesions show intra- or subcorneal collections of neutrophils with a few eosinophils. The pigmented macules demonstrate basal and supra-basal increase in pigmentation, without any pigmentary incontinence.[9] Like ETN, TNPM also needs no treatment and it resolves spontaneously.

Miliaria pustulosa

Miliaria is a condition characterized by crops of superficial vesicles resulting from sweat retention due to obstruction of sweat glands within the stratum corneum or deeper in the epidermis. It is common in the neonates probably because of immaturity of the sweat pores, warm and humid environment and excessive clothing.[10]

Four types of miliaria have been described namely miliaria crystalline, miliaria rubra, miliaria pustulosa, and miliaria profunda. When superficial vesicles of miliaria become pustular, it is known as miliaria pustulosa. The lesions of miliaria pustulosa are not the result of secondary infection and are self-limiting but can get secondarily infected and can be associated with pruritus. Lesions can be distributed over upper back, flexures, forehead, and neck[11,12] [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

A neonate with numerous superficial small pustules on the forehead and upper limbs

Staining of the pustular contents with Wright's stain shows sparse squamous cells. Histopathology is characterized by intracorneal or subcorneal vesicles in communication with sweat ducts. Sweat ducts often contain amorphous PAS positive plug.[13] Systemic antihistamines can be prescribed for the associated pruritus along with a topical soothing agent like calamine lotion.

Infantile acropustulosis

This is a condition characterized by recurrent crops of pruritic, sterile vesiculopustules with a predilection for the palms and soles. Onset is usually in the first 3 months of life but lesions may sometimes be present at birth. Individual lesions appear to start as tiny, red papules, which evolve into vesicles and then pustules over about 24 h.[14] Though the lesions principally appear on the soles and sides of the feet, and on the palms, but lesions can also occur on the dorsa of the feet, hands, fingers, ankles, and forearms.[15] Excoriation results in erosions and then crusts and finally heals with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. Lesions are intensely itchy and has a tendency to recur at intervals of 2–4 weeks in most cases, while each crop lasts for 7 to 14 days.[16] The attacks occur with gradually diminishing numbers of lesions, and with decreasing frequency, until they cease altogether, usually within 2 years of the onset.[17] Smears from the pustule content show predominance of eosinophils and later neutrophils. Cultures are sterile. Histopathology would reveal well-circumscribed subcorneal or intraepidermal aggregations of neutrophils with a sparse lymphohistiocytic infiltrates in the papillary dermis.[18]

Infantile acropustulosis is generally unresponsive to therapy. Dapsone may relieve symptoms within 24 h and signs within 72 h in some cases. Oral antihistamines help decrease the pruritus.[19] The condition may be difficult to differentiate from scabies, for which a therapeutic trial may be indicated.

Eosinophilic pustulosis

It is also known as eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. It has been suggested that eosinophilic pustulosis and infantile acropustulosis may be different manifestations of a single disorder.[20] It is characterized by recurrent crops of pruritic annular or polycyclic plaques, composed of coalescing sterile papulopustules on the seborrheic areas of the scalp, face, trunk, and extremities. They resolve spontaneously without scarring after evolving through a crusted phase of 5–10 days to heal with hyperpigmented macules and recurs approximately every 2–8 weeks.[21] Onset is most likely in the first 6 months of life and approximately 25% of them present at or just after birth. Spontaneous resolution occurs mostly between 4 and 36 months.[22,23] Though there is the absence of systemic symptoms, patients usually have associated peripheral eosinophilia and leukocytosis. Wright stain smear of pustular contents demonstrate abundant eosinophils. Histopathology would show perifollicular and periappendageal inflammatory infiltrates in upper- and mid-dermis, composed mainly of eosinophils together with neutrophils and mononuclear cells. The hair follicles themselves show spongiotic degeneration of the outer root sheath, with a necrotic centre.

Antihistaminics are indicated for pruritus. Although not consistently effective, mid to high potency topical steroids can reduce pruritus and hasten involution of lesions.

Sebaceous gland hyperplasia and Neonatal acne

The sebaceous glands of neonates produce a considerable amount of sebum in the first few weeks of life due to the effects of maternal androgens. Many infants have tiny papulopustules admixed with comedones over nose, forehead and cheeks as a result of the sebaceous hyperplasia during the first 3 months of life. Later the glands atrophy, seborrhea declines, and lesions disappear spontaneously over next 2 to 3 months. The infants are always in good health.[24,25] Endocrine investigations are only warranted in the presence of other features of androgenicity. Most cases of neonatal acne do not require treatment. Severe resistant cases can be treated similarly to adult acne with comedolytics such as topical retinoids, topical antimicrobial like benzoyl peroxide or systemic therapy with oral antibiotics[26,27] [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

A five days old neonate with sebaceous gland hyperplasia over nose

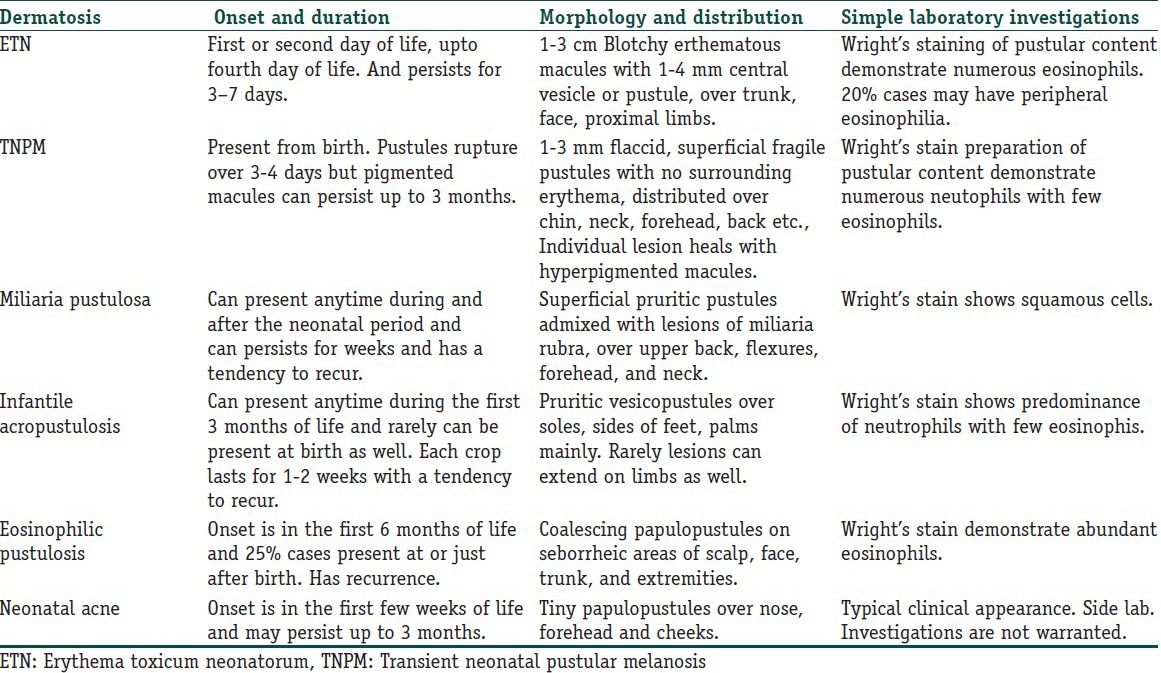

Transient neonatal cephalic pustulosis

Also termed as neonatal malasezzia furfur pustulosis (NMFP). Was historically referred wrongly as neonatal acne because of their clinical similarity. It presents in the first 3 weeks of life, characterized by erythematous papulopustules, surrounded by erythematous halo, on the cheeks, chin, eyelids, neck and upper chest in an otherwise healthy neonate. It has been postulated that Malasezzia furfur is the causal agent of neonatal cephalic pustulosis and is actually the neonatal variant of pityriasis folliculitis seen in adults but this theory is still debated for a definite conclusion.[28] The absence of comedones and presence of pustules surrounded by erythematous halo help to differentiate this entity from neonatal acne. The following criterion was suggested to define this entity: (1) pustules on face and neck, (2) age at onset, younger than 1 month, (3) isolation of M. furfur by direct microscopy in pustular material, (4) elimination of other causes of pustular eruption, (5) response to topical ketoconazole therapy.[29] Treatment is usually not required because of its self-limiting nature, and it heals within 3 months without scarring. If persistent then topical ketoconazole may be beneficial[30] [Table 1].

Table 1.

Transient benign pustular dermatosis of neonate

Pustular eruption of transient myeloproliferative disorder

Transient myeloproliferative disorder is a myeloid disorder is a rare entity that affects 10–20% of newborn with down syndrome or neonates with 21 trisomy mosaicism, which can rarely be accompanied by vesiculopustular eruption on an erythematous background. The face, especially the cheeks are the most commonly involved site but lesion can also come on trunk and extremities, especially on sites of trauma such as venepuncture sites or under adhesive tape.[31] There is an associated high white blood cell count, often with the presence of blasts. They diminish spontaneously in 1 to 3 months, paralleled by decrease in white cell count. Blast cells in smear prepared from superficial pustules within 3 days of eruption can confirm the diagnosis. Skin biopsy shows intraepidermal pustules with a perivascular dermal infiltrate of neutrophils, eosinophils, and atypical mononuclear cells.[32]

Pustular psoriasis

Infantile generalized pustular psoriasis is a rare entity that can very rarely be present in neonatal period.[33] The neonate may develop sudden onset generalized sterile pustular eruption, disseminated over the trunk, extremities, nail beds, palms, and soles with a predilection for flexors and diaper areas. The child may appear toxic with fever and myalgia with elevated acute phase reactants like leucocytes and C reactive proteins etc.[33] Early diagnosis with treatment is necessary to prevent severe complications such as bacterial superinfection, dehydration, and sepsis. Skin biopsy would reveal hypogranulosis, subcorneal neutrophilic pustules, and lymphohistiocytic perivascular infiltrates in the superficial dermis. Considering the young age, topical emollients and corticosteroids are usually the first option. Other agents that can be given are topical calcipotriol, topical pimecrolimus, systemic acitrin etc.[34,35] But if the disease severity is more, the course is usually fulminant and prolonged.

Infectious pustular eruption

Bacterial

Primary bacterial cutaneous infection in neonates can manifest as pustular lesions such as bullous impetigo and follicular lesions like folliculitis or periporitis. Most commonly implicated bacteria are Staphylococcus aureus and β-hemolytic streptococci. Apart from these congenital syphilis, caused by haematogenous transfer of Treponnema pallidum from mother, can also manifest as pustular lesions. Secondary bacterial cutaneous infection is where a primary dermatosis is secondarily infected with bacteria.

Bullous impetigo: Bullous impetigo is caused by phase group II Staphylococcus aureus, which represents a localized manifestation of subgranular epidermolysis caused by staphylococcal exfoliative toxins.[36] The toxins are localized to the area of infection and S. aureus can be cultured from the blister content. Lesions are distributed mainly over peri-oral area, around the nares, inguinal area, and buttocks. The initial lesion is a faint red macule that is superseded rapidly by a distinct superficial vesicle, which enlarges and remains intact to form bullae that turns pustular over 2–3 days. The bullae are fragile, corresponding to their subcorneal level of formation and tend to rupture to form annular or circinate rims of scale with central erythema admixed with typical honey-crusted impetigo. The lesions may be self-limited, but usually this untreated disease may persist and spread. Oral semisynthetic penicillinase resistant penicillin such as dicloxacillin, amoxicillin etc., are the most reliable treatment for bullous impetigo. Topical treatment options are mupirocin and fusidic acid[37,38] [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

A 10-days-old baby with multiple pus filled distinct fragile bullae in the groin

Folliculitis and furuncle: It is usually seen in immunocompromised neonates. Here the pyoderma is anatomically confined to the hair follicle and perifollicular structures. Most commonly implicated pathogen in neonates for folliculitis is S. aureus. Superficial staphylococcal folliculitis is known as Bockhart's impetigo, which starts as painful small pustules in follicular orifice with a halo perifollicular erythema. Risk factors are occlusion, overhydration, maceration, tropical climates and poor hygiene. It may also occur when a hair follicle is blocked by tape, dressing or mechanically traumatized. Deep folliculitis with extensive perifollicular inflammation and abscess formation produces a lesion known as furuncle[38,39] [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Multiple inflamed follicular lesions on the back of a neonate

Topical mupirocin, erythromycin or clindamycin may be effective for superficial and limited folliculitis. Widespread or deep folliculitis requires oral antistaphylococcal antibiotics.[39]

Secondary bacterial infection

Congenital syphilis: The primary stage is absent in congenital syphilis as the disease is blood borne and it corresponds with the secondary stage of adult syphilis and can present with various cutaneous lesions like secondary syphilis, that is, maculopapular lesions, vesicobullous lesions, condylomata lata, and pustular lesions. Pustular lesions of congenital syphilis are distributed symmetrically over palms and soles, peri-oral area, trunk, buttocks, and genitalia. The content of these pustules are seropurulent fluid, teemed with spirochetes.[40] Demonstration of T. pallidum by direct examination will confirm the diagnosis. A positive nontreponemal test (VDRL) in titre higher than the mother or a rising titre in serial monthly test suggests a prenatal infection. For definitive diagnosis treponemal test can be done. Treatment is offered with either aqueous crystalline penicillin G, or procaine penicillin or Benzathine penicillin G.[41]

Listeriosis: Listeriosis is a septicaemic disease caused by Listeria monocytogenes, an aerobic, Gram positive rod. In neonates early-onset infection is acquired in utero; late onset infection may be acquired during passage through birth canal or after birth via contaminated food. Incubation period is probably 21 days. It can manifests in a neonate as grey–white maculapapules with vesicles or pustules, associated with septicaemia or meningitis.[42] The organism can be recovered in routine cultures from blood or CSF, but special techniques may be necessary to isolate Listeria. Treatment of choice is the combination of amoxicillin and tobramycin.[43]

Fungal

Fungal infections in a neonate should be suspected when discrete pustular lesions are present with a background of erythema. Cutaneous candidiasis, Malassezia pustulosis are the two possibilities for pustulosis due to fungal element. Cutaneous candidiasis in a neonate can either be congenital or neonatal.

Congenital candidiasis: Congenital candidiasis results due to intrauterine candidal infection of fetus. Intrauterine contraceptive device or cervical sutures or any other intrauterine foreign body can be possible risk factors for transmission of infection. Onset of cutaneous lesions usually starts within 6 days of life. The lesions are discrete vesicles or pustules on an erythematous base, distributed over face, chest, trunk and palms and soles. Most cases are self-limiting, but topical nystatin is recommended to prevent dissemination of disease to lungs. Diagnosis can be made by identification of spores and pseudohyphae of C. albicans in skin scraping and culture of the organism.[44,45]

Neonatal candidiasis: It is perinatally acquired candidal infection, manifesting after sixth day of life. The infection is acquired during the passage through the birth canal or later through nursery contacts. Spectrum of the disease can range from a diffuse skin eruption in the absence of systemic illness to severe systemic disease resulting in early neonatal death. Presentation can be in the form of oral thrush, flexural pustular eruption as perianal and diaper dermatitis. The systemic form presents especially in premature infants with erosive crusted plaques.[46]

Malassezia pustulosis: Also known as pityrosporum folliculitis, which is usually seen as a disorder of adolescents and young adults, but may be a rare cause of folliculitis in neonates. Cutaneous lesions are follicular papules and sparse pustules on the face and scalp. Diagnosis can be confirmed by a positive KOH and culture of pustular contents. Treatment with topical antifungals like miconazole, clotrimazole, or ketoconazole gives good result.[47,48]

Viral

Viral infections that can manifest as pustular eruption are herpes simplex infection, varicella, and cytomegalo virus infection.

Herpes simplex virus infection: Risk of neonatal infection is only 1% if mother acquires HSV in first trimester, but risk rises upto 30–50% in third trimester infection, due to production of protective antibodies.[49] Neonatal transmission takes place mainly during intrapartum period or through fomites after delivery. It manifests in one of three forms: Skin, eye, and mouth involvement; encephalitis; or disseminated disease. The latter two forms account for more than half of neonatal herpes infection. The skin lesions appear in clusters as 2 to 4 mm vesicles and pustules with surrounding erythema. Shallow mucosal ulcerations with inflammation are often seen. Disseminated skin lesions can be associated with shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, neurological complications, and multisystem failure with high mortality. Approximately 4% of all neonatal infections are transmitted in utero and results in congenital HSV infection, manifesting with microcephaly, hydrocephalus, chorioretinitis, and vesicular skin eruption.[50,51]

History and physical examination and the presence of multinucleated giant cells in Tzanck smear are sufficient to make a diagnosis. However the gold standard for diagnosis is viral culture. Polymerase chain reaction is commercially available for diagnosis of HSV encephalitis.

Ceasarean section is indicated when there is active infection at the time of delivery or when the membrane has ruptured within 6 h before onset of labor. Second and third trimester HSV infection in mother should be treated with acyclovir therapy.[52]

For severe or disseminated neonatal HSV infection, the treatment of choice is intravenous acyclovir 5–10 mg/kg every 8 h.[52]

Varicella: Varicella is caused by varicella zoster virus. Route of transmission is airborne. Varicella is potentially dangerous in newborn, in whom no protective maternal antibodies are present and the route of transmission has necessarily been hematogenous. Thus, the incubation period may be shortened and some children may even present with vesicles at birth. The prodormal phase is usually absent in neonate. Neonates born to mothers who develop chickenpox from 5 days before delivery to 2 days after are at great risk (20%) of developing severe disseminated varicella, where fetal mortality rate is between 20–30%, largely due to pneumonitis and hepatitis.[53] These neonates should receive 125–250 units of zoster immunoglobulin intramuscularly as soon as possible, preferably within 72 h.[54] When the infant is born 5 days after maternal infection, the risk are similar to those of other infants. Clinically lesions start with clear fluid-filled vesicles that later turn pustular and eventually scab. New crops of lesions appear for an average of 3–4 days, continuing for up to 7 days. Secondary bacterial infection is the most common complication. Healthy babies seldom develop more serious side effects like pneumonitis, encephalitis, Reye syndrome. Clinical presentation makes diagnosis easy, however Tzanck smear, serology to demonstrate seroconversion on acute and convalescent paired sera, immunofluoresence microscopy to demonstrate monoclonal antibody can help to confirm diagnosis [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

‘Neonatal varicella’ in a 4-day old child, whose mother had chicken-pox before delivery

Recommended dose of acyclovir for VZV infection is 20–40 mg/kg orally four times/day for 5 days, but it is not recommended routinely for the treatment of chickenpox in healthy children. Newborns who are immunocompromised the recommended dose is 10–20 mg/kg every 8 h for 7–10 days.[55]

But when the maternal infection occurs during 8–20 weeks of pregnancy, there is a 2% risk of developing varicella embryopathy known as ‘fetal varicella syndrome’. In FVS, the newborn presents with LBW, scars in dermatomal distribution, eye defects (cataract, microphthalmia and chorioretinitis), bone and muscle hypoplasia and neurological abnormalities (mental retardation, microcephaly and dysfunction of bladder and sphincter. When the maternal infection occurs after 20 weeks of gestation, there is an increased risk of these children developing herpes zoster in early life.[56]

Conclusions

Neonatal pustular eruptions are common cutaneous lesions seen within the first 4 weeks of life. While the differential diagnosis is extensive, simple diagnostic methods can aid in differentiating between them. Given their ubiquitous presentation, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate among self-limiting noninfectious pustular dermatosis such as erythema toxicum neonatorum, transient neonatal pustular melanosis, miliaria putulosa etc., and potentially life threatening infections such as herpes simplex virus, varicella zoster virus infections. But a clear knowledge and understanding of each entity with its clinical presentation, progression, prognosis and treatment would enable a dermatologist to offer correct diagnosis and treatment and avoid needless confusion.

What is new?

This review article is an attempt towards compiling the differentiating features of all the important pustular dermatosis seen in a newborn, in terms of etiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, management and prognosis, and would provide an hands-on overview to a practicing dermatologist regarding these entities.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Nanda A, Kaur S, Bhakoo ON, Dhall K. Survey of cutaneous lesions in Indian newborns. Pediatr Dermatol. 1989;6:39–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1989.tb00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keitel HG, Yadav V. Etiology of toxic erythema. Am J Dis Child. 1963;106:306–9. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1963.02080050308010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hidano A, Purwoko R, Jitsukawa T. Statistical survey of skin changes in Japanese neonates. Pediatr Dermatol. 1986;3:140–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1986.tb00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang MW, Orlow SJ. Neonatal, Pediatric, and Adolescent Dermatology. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. Vol. 1. New York: Mc Graw Hill Medical; 2008. pp. 935–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox JN, Walton RG, Gottlieb B, Castellano A. Pigmented skin lesions in black newborn infants. Cutis. 1970;24:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrándiz C, Coroleu W, Ribera M, Lorenzo JC, Natal A. Sterile transient neonatal pustulosis is a precocious form of erythema toxicum neonatorum. Dermatology. 1992;185:18–22. doi: 10.1159/000247396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auster B. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis. Cutis. 1978;22:327–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Praag MC, Van Rooij RW, Folkers E, Spritzer R, Menke HE, Oranje AP. Diagnosis and treatment of pustular disorders in the neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:131–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1997.tb00221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramamurthy RS, Reveri M, Esterly NB, Fretzin DF, Pildes RS. Transient neonatal pustular melanosis. J Pediatr. 1976;88:831–5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(76)81126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Loewenthal LJ. Pathogenesis of miliaria. The role of sodium chloride. Arch Dermatol. 1961;84:2–17. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1961.01580130008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mallory SB. Neonatal skin disorders. Ped Clin North Am. 1991;38:745–62. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)38152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Straka BF, Cooper PH, Greer KE. Congenital miliaria crystalline. Cutis. 1991;47:103–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holzle E, Kligman AM. The pathogenesis of miliaria rubra. Role of the resident flora. Br J Dermatol. 1978;99:117–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb01973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jennings JL, Burrows WM. Infantile acropustulosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:733–7. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)70187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarratt M, Ramsdell W. Infantile acropustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:834–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFadden N, Falk ES. Infantile acropustulosis. Cutis. 1985;36:49–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nguyen J, Strobel M, Arnaud JP, Sibille G, Chabanne A, Lacave J. Acropustulose infantile: Expression inhabituelle de la gale chez le nourrison? Ann Pediatr. 1991;38:479–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finday RJ, Odom RB. Infantile acropustulosis. Am Dis Child. 1986;137:455–7. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1983.02140310037009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kahn G, Rywlin AM. Acropustulosis of infancy. Arch Dermatol. 1979;115:831–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vicente J, España A, Idoate M, Iglesias ME, Quintanilla E. Are eosinophilic pustular folliculitis of infancy and infantile acropustulosis the same entity? Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:807–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Onorato J, Heilman ER, Laude TA. Pruritic pustular eruption in an infant.(clinical conference) Pediatr Dermatol. 1994;10:292–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1993.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picone Z, Madile BM. Eosinophilic pustular folliculitis (Ofuji's disease) in a newborn. Pediatr Dermatol. 1992;9:178. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buckley DA, Munn SE, Higgins EM. Neonatal eosinophilic pustular folliculitis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26:251–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedane C, Souyri N. Les acnes induites. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1990;117:53–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigurdsson V, De Wit RF, De Groot AC. Infantile acne. Br J Dermatol. 1991;125:285–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cunliffe WJ, Baron SE, Coulson IH. A clinical therapeutic study of 29 patients with infantile acne. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:463–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas J. Neonatal dermatoses: An overview. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1999;65:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niamba P, Weill FX, Sarlangue J, Labreze C, Couprie B, Thaieb A. Is common neonatal cephalic pustulosis (neonatal acne) triggered by Malassezia sympodalis? Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:995–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.8.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapelanoro R, Mortureux P, Couprie B, Maleville J, Taieb A. Neonatal Malassezia furfur pustolosis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:190–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Araújo T, Schachner L. Benign vesicopustular eruptions in the neonate. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;4:359–66. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viros A, Garcia-Patos V, Aparicio G, Tallada N, Bastida P, Castells A. Sterile neonatal pustulosis associated with transient myeloproliferative disorder in twins. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1053–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burch JM, Weston WL, Rogers M, Morelli JG. Cutaneous pustular leukemoid reactions in trisomy 21. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:232–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2003.20310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Su YS, Chen GS, Lan E CC. Infantile generalized pustular psoriasis: A case report and review of literature. Dermatologica Sinica. 2011;29:22–4. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi YJ, Hann SK, Chang SN, Park WH. Infantile psoriasis: Successful treatment with topical calcipotriol. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:242–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2000.00024-3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Al-Shobaili H, Al-Khenaizan S. Childhood generalized pustular psoriasis: Successful treatment with isotretinoin. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:563–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amagai M, Matsuyoshi N, Wang ZH, Andl C, Stanley JR. Toxin in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome targets desmoglein 1. Nature Med. 2000;6:1275–7. doi: 10.1038/81385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dajani AS, Ferrieri P, Wannamaker LW. Endemic superficial pyoderma in children. Arch Dermatol. 1973;108:517–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hlady WG, Middaugh JP. An epidemic of bullous impetigo in a newborn nursery due to Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology and control measures. Alsaka Med. 1986;28:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Everett ED, Dellinger P, Goldstein EJ, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1373–406. doi: 10.1086/497143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rangiah PN. Syphilis and Infancy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1961;27:165–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Humphrey MD, Bradford DL. Congenital syphilis: Still a reality in 1996. Med J Aust. 1996;165:382–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb125025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barber M, Okubadejo OA. Maternal and neonatal listeriosis: Report of case and brief review of literature of listeriosis in man. Br Med J. 1965;2:735. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5464.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon RC, Barret FF, Clark DJ. Influence of several antibiotics, singly and in combination, on the growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Pediatr. 1972;80:667. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(72)80072-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Darmstadt GL, Dinulos JG, Miller Z. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis: Clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management guidelines. Pediatrics. 2000;105:438–44. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.2.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jagtap SA, Saple PP, Dhaliat SB. Congenital cutaneous candidiasis: A rare and unpredictable disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:92–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.77564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowen JL, Atkins JT, Levy ML, Baer SC, Baker CJ. Invasive fungal dermatitis in the <1000-gram neonate. Pediatrics. 1995;95:682–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.De Araújo T, Schachner L. Benign vesicopustular eruptions in the neonate. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;4:359–66. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borderon JC, Langier J, Vaillant MC. Colonisation du nouveau-ne par Malassezia furfur. Bull Soc Fr Mycol Med. 1989;1:129–32. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Website. Sexually transmitted disease guidelines. [Last accessed on 2010]. Available form: http://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/2006/rr5511.pdf .

- 50.Jones CL. Herpes simplex virus infection in the neonate: Clinical presentation and management. Neonatal Newt. 1996;15:11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jacobs RE. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. Semin Perinatol. 1998;22:64–71. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(98)80008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Infectious Diseases. 2000 Red book: Report of the committee on infectious diseases. In: Pickering LK, editor. 25th ed. Elk Grove Village, I11: United States: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2000. pp. 309–18. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tan MP, Koren G. Chickenpox and pregnancy: Revisited. Reprod Toxicol. 2005;21:410–20. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller E, Cradock-Watson JE, Ridehalgh MK. Outcome in newborn babies given anti-varicella-zoster immunoglobulin after perinatal maternal infection with varicella zoster virus. Lancet. 1989;2:371–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90547-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitney RJ, Gnann JW. Acyclovir: A decade later. N Engl J Med. 1992:327. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209103271108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Araújo T, Schachner L. Benign vesicopustular eruptions in the neonate. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;4:359–66. [Google Scholar]