Abstract

Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis (LRC) is an unusual form of acute cutaneous leishmaniasis. Herein, we present a case of LRC of the lips mimicking granulomatous cheilitis. An 8-year-old, Syrian child admitted with a swelling and disfigurement of his lips for 4 years. Abundant intra and extracellular Leishmania amastigotes were determined in the smear prepared from the lesion with Giemsa stain. Histopathology showed foamy histiocytes and leishmania parasites within the cytoplasm of macrophages in the epidermis and a dense dermal mixed type inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, foamy histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells. On the basis of anamnestic data, the skin smears results, clinical and histopathologic findings, LRC was diagnosed. The patient was treated with meglumine antimoniate intramuscularly and fluconazole orally. Cryotherapy was applied to the residual papular lesions. The lesion improved markedly at the first month of the treatment.

Keywords: Granulomatous cheilitis, leishmaniasis recidiva cutis, lip

What was known?

Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis is an unusual form of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a protozoan disease caused by the protozoa Leishmania subtypes and transmitted by the bite of an infected female sand-fly. Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis (LRC) is an unusual form of CL. It appears after a variable period of time (from months to years) in the same area as, or very close to the old scar of, a previous acute lesion healed apparently.[1]

Herein, we present a case of a large and horrifying example of LRC of the lips mimicking granulomatous cheilitis.

Case Report

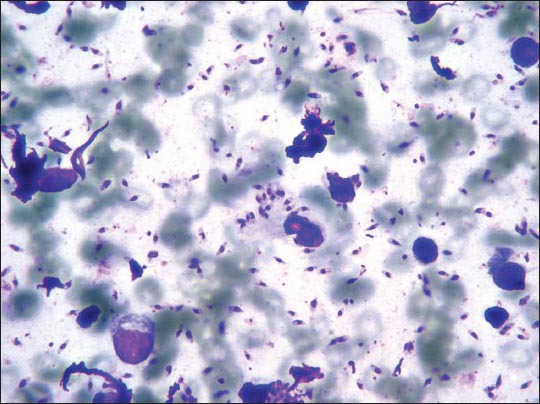

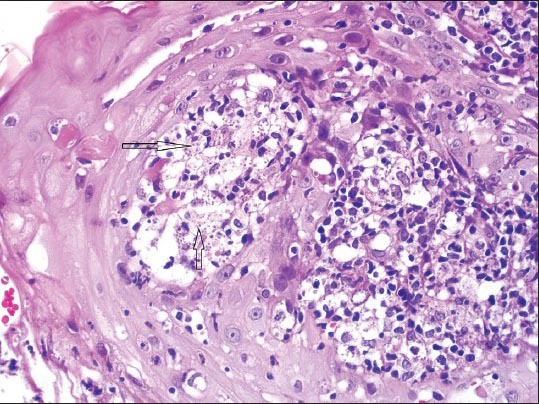

An 8-year-old, healthy, Syrian boy was admitted to our outpatient clinic of dermatology with a swelling and disfigurement of his lips existing for the last 4 years. The initial lesion had started as asymptomatic papules, 0.5-1 cm in diameter on cheek and lip when he was two years old. After the treatment with intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime(R)) in Syria at that time, the lesions disappeared; however, cribriform scarring on the lip and cheek remained. Two years later, new lesions began as papules, 1 cm in diameter around the cribriform scars on the lips and cheeks. Dermatologic examination showed the presence of a severe swelling and purulent draining, crusty infiltrated granulomatous plaques on the lower and upper lips. A 5 cm cribriform scarring and 1 cm papule on this scar were seen on the left cheek [Figures 1a and b]. General physical examination did not show any pathological findings. Regional lymph nodes were not involved. Laboratory tests revealed Hb 10.3 g/dl (12.2-18.1 g/dl), Hct 30.5% (37.7-53.7%), sedimentation rate 70 mm/h (0-12 mm/h), C reactive protein 42.4 mg/dl (0-5 mg/dl). Abundant intra and extracellular Leishmania amastigotes were determined in the smear prepared from the lesion with Giemsa stain [Figure 2]. Histopathology showed foamy histiocytes and leishmania parasites within the cytoplasm of macrophages in the epidermis and a dense dermal mixed type inflammatory cell infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and foamy histiocytes with multinucleated giant cells [Figure 3]. On the basis of these findings, LRC was diagnosed. The patient was treated with 20 mg/kg/day systemic meglumine antimoniate intramuscularly, for 20 days. Because the healing was slow, he was also prescribed oral fluconazole 5 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks. Cryotherapy was applied to the residual papular lesions. The lesion improved markedly at the first month of the treatment [Figures 1c and d].

Figure 1.

Clinical pictures of the patient before treatment (a and b) and after 1 month of the treatment (c and d)

Figure 2.

Abundant intra and extracellular Leishmania amastigotes in the smear (Giemsa stain, ×100)

Figure 3.

Leishmania parasites (black arrows) in the cytoplasm of macrophages (H and E, ×400)

Discussion

In LRC, the actual cause of reactivation of the disease is unclear; insufficient treatment or the use of non-effective drugs may be possible causes of recurrence, but the most identified theory is a defect in the T-lymphocyte activation by the protozoa and the inability of the macrophages to kill all amastigotes.[1,2] Clinically, differential diagnosis includes lupus vulgaris, bacterial infections, pseudolymphoma and squamous cell carcinoma and when the lesions found on the lips syphilitic chancre, granulomatous cheilitis, Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome and foreign body granuloma should be considered.[1,3] The treatment for LRC includes systemic therapy with pentavalent antimony, alone or in combination with allopurinol, and amphotericin B, and local therapy with intralesional antimonials, cryosurgery, or excision.[2] In children, fluconazole may represent an effective and well-tolerated therapy.[4]

Few cases of LRC have been reported previously.[1,5,6,7,8,9] These lesions can have variable clinical appearance. To our knowledge, lips of LRC mimicking granulomatous cheilitis have not been reported so far. The difference of our case from other cases is that our patient is a child, he had a very giant lesion and lesion was located on the lip. We consider there is unusually abundant amastigotes because of unavailability of a sufficient therapy due to existing social situations.

In summary, we want to report a case with a large and horrifying example of LRC of the lips mimicking granulomatous cheilitis. The absence of PCR examination is a limitation of our study. Considering the different forms of the disease nature, any unusual skin lesion located on the lips in an endemic area should always be investigated for CL and thus, clinicians should have a high level of suspicion to make a diagnosis of LRC and an appropriate treatment.

What is new?

Considering the different forms of the disease nature, any unusual skin lesion in an endemic area should always be investigated for cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Clinicians should have a high level of suspicion to make a diagnosis of leishmaniasis recidiva cutis and an appropriate treatment.

Footnotes

Source of support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Cannavò SP, Vaccaro M, Guarneri F. Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:205–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Momeni AZ, Aminjavaheri M. Treatment of recurrent cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:129–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1995.tb03598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veraldi S, Bottini S, Persico MC, Lunardon L. Case report: Leishmaniasis of the upper lip. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:659–61. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sklavos AV, Walls T, Webber MT, Watson AB. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in a child treated with oral fluconazole. Australas J Dermatol. 2010;51:195–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stefanidou MP, Antoniou M, Koutsopoulos AV, Neofytou YT, Krasagakis K, Krüger-Krasagakis S, et al. A rare case of leishmaniasis recidiva cutis evolving for 31 years caused by Leishmania tropica. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:588–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calvopina M, Uezato H, Gomez EA, Korenaga M, Nonaka S, Hashiguchi Y. Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis due to Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis in subtropical Ecuador: Isoenzymatic characterization. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:116–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2004.02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calvopina M, Gomez EA, Uezato H, Kato H, Nonaka S, Hashiguchi Y. Atypical clinical variants in New World cutaneous leishmaniasis: Disseminated, erysipeloid, and recidiva cutis due to Leishmania (V.) panamensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73:281–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira-Neto MP, Mattos M, Souza CS, Fernandes O, Pirmez C. Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis in New World cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 1998;37:846–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1998.00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bittencourt AL, Costa JM, Carvalho EM, Barral A. Leishmaniasis recidiva cutis in American cutaneous leishmaniasis. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:802–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]