Abstract

We examined the effect of conformational change at the β7 I-like/hybrid domain interface on regulating the transition between rolling and firm adhesion by integrin α4β7. An N-glycosylation site was introduced into the I-like/hybrid domain interface to act as a wedge and to stabilize the open conformation of this interface and hence the open conformation of the α4β7 headpiece. Wild-type α4β7 mediates rolling adhesion in Ca2+ and Ca2+/Mg2+ but firm adhesion in Mg2+ and Mn2+. Stabilizing the open headpiece resulted in firm adhesion in all divalent cations. The interaction between metal binding sites in the I-like domain and the interface with the hybrid domain was examined in double mutants. Changes at these two sites can either counterbalance one another or be additive, emphasizing mutuality and the importance of multiple interfaces in integrin regulation. A double mutant with counterbalancing deactivating ligand-induced metal ion binding site (LIMBS) and activating wedge mutations could still be activated by Mn2+, confirming the importance of the adjacent to metal ion-dependent adhesion site (ADMIDAS) in integrin activation by Mn2+. Overall, the results demonstrate the importance of headpiece allostery in the conversion of rolling to firm adhesion.

Integrins are a family of heterodimeric adhesion molecules with noncovalently associated α and β subunits that mediate cell-cell, cell-matrix, and cell-pathogen interactions and that signal bidirectionally across the plasma membrane (1, 2). The affinity of integrin extracellular domains is dynamically regulated by “inside-out” signals from the cytoplasm. Furthermore, ligand binding can induce “outside-in” signaling and activate many intracellular signaling pathways (3-6). Integrin extracellular domains exist in at least three distinct global conformational states that differ in affinity for ligand (5, 7); the equilibrium among these different states is regulated by the binding of integrin cytoplasmic domains to cytoskeletal components and signaling molecules (4, 6).

Integrin affinity regulation is accompanied by a series of conformational rearrangements. Electron micrographic studies of integrins αVβ3 and α5β1 demonstrate that ligand binding, in the absence of restraining crystal lattice contacts, induces a switchblade-like extension of the extracellular domain and a change in angle between the I-like and hybrid domains (5, 7). Recent crystal structures of integrin αIIbβ3 in the open, high affinity conformation demonstrate that the C-terminal α7-helix of the β I-like domain moves axially toward the hybrid domain, causing the β hybrid domain to swing outward by 60°, away from the α subunit (8). This conversion from the closed to the open conformation of the ligand-binding domains in the integrin headpiece also destabilizes the bent conformation and induces integrin extension in which the headpiece extends and breaks free from an interface with the leg domains that connect it to the plasma membrane. To stabilize the outward swing of the hybrid domain and the high affinity open headpiece conformation, glycan wedges have been introduced into the interface between the hybrid and I-like domains of β3 and β1 integrins (9). The relation between hybrid domain swing-out and high integrin affinity has also been strongly supported by the study of an allosteric inhibitory β1 integrin antibody SG19, which binds to the outer side of the I-like hybrid domain interface and prevents hybrid domain swing-out as shown by electron micrographic image averages (10). Allosteric inhibition by this mAb1 was confirmed because it did not inhibit ligand binding to the low affinity state but rather inhibited conversion to the high affinity state. Binding of SG19 mAb to the β1 wedge mutant was dramatically decreased compared with wild-type, further supporting induction of hybrid domain swing-out by the wedge mutant. Conversely, allosteric activating mAbs have been shown to map to the face of the β hybrid domain that is closely opposed to the α subunit in the closed conformation and therefore appear to induce the high affinity state by favoring hybrid domain swing-out (11). Disulfide cross-links in the β6–α7 loop (12) and shortening of the α7-helix in the I-like domain (13) also support the conclusion that downward displacement of the α7-helix induces high affinity for ligand. A homologous α7-helix displacement in integrin α subunit I domains similarly induces high affinity for ligand (14).

It has long been known that integrin affinity for ligand is strongly influenced by metal ions, and recently the basis for this regulation has been deduced for the integrin α4β7 (15). The integrin α4β7 binds the cell surface ligand mucosal cell adhesion molecule-1 (MAdCAM-1) and mediates rolling adhesion by lymphocytes in postcapillary venules in mucosal tissues and the subsequent firm adhesion in endothelium and trans-endothelial migration. These key steps in lymphocyte trafficking in vivo can be mimicked in vitro by introducing α4β7 transfected cells into parallel wall flow chambers with MAdCAM-1 coated on the lower wall. In Ca2+ and Ca2+/Mg2+, α4β7 mediates rolling adhesion, whereas in Mg2+, Mn2+, or when α4β7 is activated from within the cell, α4β7 mediates firm adhesion (15-17). Unliganded-closed and liganded-closed structures of αVβ3 have revealed a linear array of three divalent cation binding sites in the I-like domain (18, 19). The metal coordinating residues in β3 are 100% identical to those in β7. Mutation of these residues in β7, and studies of synergy between Ca2+ and Mg2+ and competition between Ca2+ and Mn2+, revealed the following (15). 1) The middle of the three linearly arrayed sites, the metal ion-dependent adhesion site (MIDAS), is absolutely required for rolling and firm adhesion, and it can bind to MAdCAM-1 (and presumably coordinate) either through Ca2+, Mg2+, or Mn2+. 2) The adjacent to MIDAS (ADMIDAS) metal ion binding site functions as a negative regulatory site that stabilizes rolling adhesion. Its mutation results in firm adhesion in Ca2+, Mg2+, or Mn2+. Furthermore, Ca2+ exerts negative regulation at high concentrations at this site by favoring the closed I-like domain conformation, and Mn2+ activates integrins by competing with Ca2+ at this site and favoring an alternative coordination geometry seen in the open I-like domain conformation. 3) The ligand-induced metal binding site (LIMBS) functions as a positive regulatory site that favors firm adhesion. Its mutation results in rolling adhesion in Ca2+, Mg2+, or Mn2+. Furthermore, synergism between low concentrations of Ca2+ and Mg2+ results from their binding to the LIMBS and MIDAS, respectively.

Despite these advances in understanding the mechanism by which metal ions stabilize alternative conformations of integrin β I-like domains, several issues remain unresolved. How do the closed and open conformations of the α4β7 headpiece affect rolling and firm adhesion? Does metal ion occupancy at the LIMBS and ADMIDAS or outward swing of the hybrid domain have the strongest effect on I-like domain conformation? If changes occur at both metal binding sites and the I-like/hybrid domain interface, does one dominate the other, or can they be counterbalancing or additive? Here we address these questions and the importance of allostery at the I-like/hybrid domain interface by introducing a glycan wedge mutation into the β7 subunit to stabilize the open conformation of this interface.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Monoclonal Antibodies

The human integrin α4β7-specific monoclonal antibody Act-1 was described previously (20, 21).

cDNA Construction, Transient Transfection, and Immunoprecipitation

The β7 site-directed mutations were generated by using QuikChange (Stratagene). Wild-type human β7 cDNA (22) in vector pcDNA3.1/Hygro(−) (Invitrogen) was used as the template. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Transient transfection of 293T cells using calcium phosphate precipitation was as described (23). Transfected 293T cells were metabolically labeled with [35S]cysteine and -methionine, and labeled cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with 1 μl of Act-1 mAb ascites and 20 μl of protein G agarose, eluted with 0.5% SDS, and subjected to non-reducing 7% SDS-PAGE and fluorography (24). The selected protein bands were quantified using a Storm PhosphorImager after 3 h of exposure to storage phosphor screens (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunofluorescence Flow Cytometry

Immunofluorescence flow cytometry was as described (23) using 10 μg/ml purified antibody.

Flow Chamber Assay

A polystyrene Petri dish was coated with a 5-mm diameter, 20-μl spot of 5 μg/ml purified h-MAdCAM-1/Fc in coating buffer (phosphate-buffered saline, 10 mm NaHCO3, pH 9.0) for 1 h at 37 °C followed by 2% human serum albumin in coating buffer for 1 h at 37 °C to block nonspecific binding sites (16). The dish was assembled as the lower wall of a parallel plate flow chamber and mounted on the stage of an inverted phase-contrast microscope (25).

293T cell transfectants were washed twice with Ca2+- and Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution, 10 mm Hepes, pH 7.4, 5 mm EDTA, 0.5% bovine serum albumin and resuspended at 5 × 106/ml in buffer A (Ca2+-and Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution, 10 mm Hepes, and 0.5% bovine serum albumin) and kept at room temperature. Cells were diluted to 1 × 106/ml in buffer A containing different divalent cations immediately before infusion in the flow chamber using a syringe pump.

Cells were allowed to accumulate for 30 s at 0.3 dyne cm−2. Then, shear stress was increased every 10 s from 1 up to 32 dynes cm−2 in 2-fold increments. The number of cells remaining bound at the end of each 10-s interval was determined. Rolling velocity at each shear stress was calculated from the average distance traveled by rolling cells in 3 s. To avoid confusing rolling with small amounts of movement due to tether stretching or measurement error, a velocity of 2 μm/s, which corresponds to a movement of 1/2 cell diameter during the 3-s measurement interval, was the minimum velocity required to define a cell as rolling instead of firmly adherent (26). Microscopic images were recorded on Hi8 videotape for later analysis.

Surface Calculations

Accessible surfaces were calculated with probes of the indicated radii using the buried surface routine of Crystallography and NMR System software (27).

RESULTS

Activation of α4β7 with a Glycan Wedge Mutation

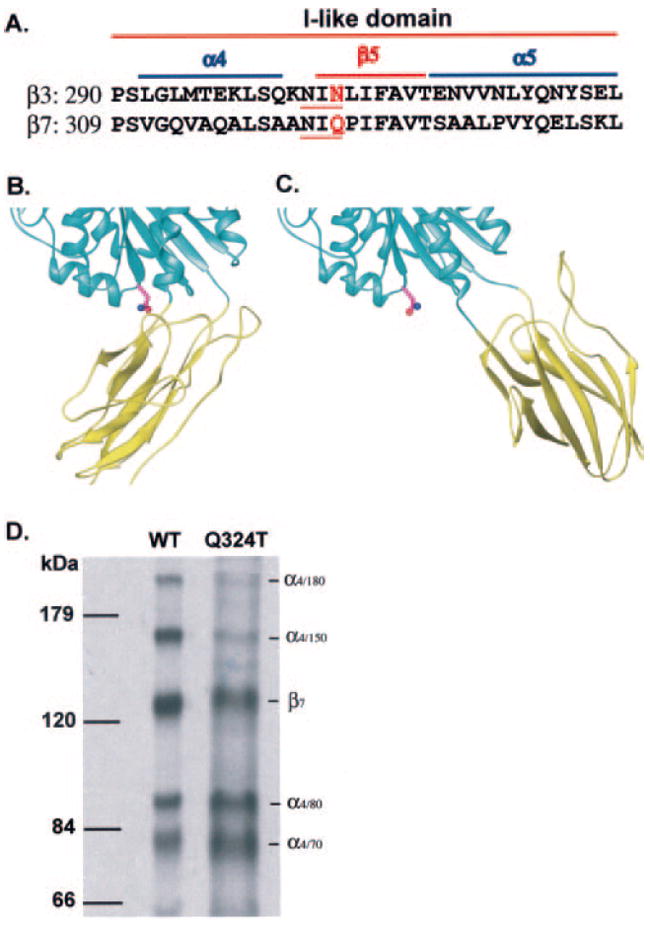

The mutation Gln-324 → Thr in β7 introduced an N-glycosylation site at Asn-322 in the α4–β5 loop of the I-like domain (Fig. 1A), the same position as used previously for the wedge mutant in the highly homologous β3 subunit (9). Crystal structures have been defined for the β3 I-like/hybrid domain interface in both closed low affinity and open high affinity conformations (5, 8, 19). In the β3 subunit, the identical Asn residue has 5-fold more solvent-accessible surface area as determined with a 1.4-Å probe radius to simulate a water molecule in the open conformation (Fig. 1C) than in the closed conformation (Fig. 1B) of the hybrid/I-like interface. To approximate the size of the first four carbohydrate residues of an N-linked glycan, we used a 10-Å probe radius (see “Materials and Methods”), and we found that the Asn side chain was accessible in the open but not the closed conformation, as would be expected from visual inspection of the interface (Fig. 1, B and C). Similarly to other wedge mutants (9), the α4β7 wedge mutant was expressed somewhat less well than wild type in 293T transfectants (Table I). Immunoprecipitation and SDS-PAGE of [35S]cysteine- and -methionine-labeled α4β7 showed a 3,000 Mr increase for the Q324T mutant β7 subunit compared with wild type, confirming N-glycosylation of the introduced site (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Design of the N-glycosylation site (wedge) mutation and confirmation by immunoprecipitation.

A, sequence alignment of the relevant portion of the human integrin β3 and β7 I-like domains. The N-glycosylation sites in β3 and β7 wedge mutants are underlined, and the residues mutated to Thr are shown in red. Helices and β-strands are labeled and overlined. B and C, the β3 I-like/hybrid domain interface. The interfaces are shown in the closed (B) (19) and open (8) (C) conformations, with the I-like and hybrid domains shown as cyan and yellow ribbons, respectively. The structures are shown in the same orientation after superposition using allosterically invariant portions of the I-like domain (8). The side chain of the Asn that is N-glycosylated in β3 and β7 wedge mutants is shown. D, lysates from 35S-labeled 293T cell transfectants were immunoprecipitated with Act-1 mAb. Precipitated wild-type (WT) and glycan wedge mutant (Q324T) materials were subjected to non-reducing 7.5% SDS-PAGE and fluorography. Positions of molecular mass markers are shown on the left, and the integrin bands are indicated on the right.

Table I. Expression of α4β7 mutants.

Integrin α4β7 cell surface expression in 293T transient transfectants was determined with Act-1 mAb and immunofluorescence flow cytometry. The data are mean specific fluorescence intensity as percent of wild type (WT) ± difference from the mean for two independent experiments.

| Name | Mutation | Expression |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| % WT | ||

| Wild type | 100 ± 12 | |

| Glycan wedge | Q324T | 47 ± 3 |

| LIMBS | D237A | 99 ± 20 |

| Wedge/LIMBS | Q324T/D237A | 38 ± 10 |

| ADMIDAS | D147A | 70 ± 9 |

| Wedge/ADMIDAS | Q324T/D147A | 35 ± 8 |

During maturation and processing of α4β1 and α4β7, a portion of the intact α4 subunit, which migrates at 150,000 and 180,000 Mr, is cleaved to fragments of 80,000 and 70,000 Mr (28-31). Cleavage occurs after a dibasic Lys-Arg sequence in the α4 thigh domain (29, 31). Activation of T lymphocytes increases cleavage of the α4 subunit (29, 32, 33). Interestingly, addition of the glycan wedge markedly increased α4 subunit cleavage from 51% (wild type) to 90% (Q324T mutant) (Fig. 1C and Table II). This finding directly demonstrates that α4 integrin activation (see below) enhances proteolytic processing of the α4 subunit. This could result either from greater exposure of the cleavage site in open, extended α4β7 or longer residence in the post-endoplasmic reticulum compartments where processing occurs (34).

Table II. Effect of the glycan wedge in α4β7 on cleavage of α4 subunit.

293T cells were transiently transfected with wild-type (WT) or mutant integrin α4β7 using calcium phosphate precipitation and metabolically labeled with [35S]cysteine and -methionine as in Fig. 1D. Labeled cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with Act-1 antibody and subjected to non-reducing 7% SDS-PAGE and fluorography. The selected protein bands were quantified using a Storm PhosphorImager after 3 h of exposure to storage phosphor screens. The percent of radioactivity in each α4 subunit band was calculated, and cleavage was calculated as percent of (α4/80 + α4/70)/(α4/180 + α4/150 + α4/80 + α4/70).

| Radioactivity in each α4 subunit band

|

Cleavage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α4/180 | α4/150 | α4/80 | α4/70 | ||

|

| |||||

| % | |||||

| WT | 10 | 39 | 25 | 26 | 51 |

| Q324T | 2 | 8 | 41 | 49 | 90 |

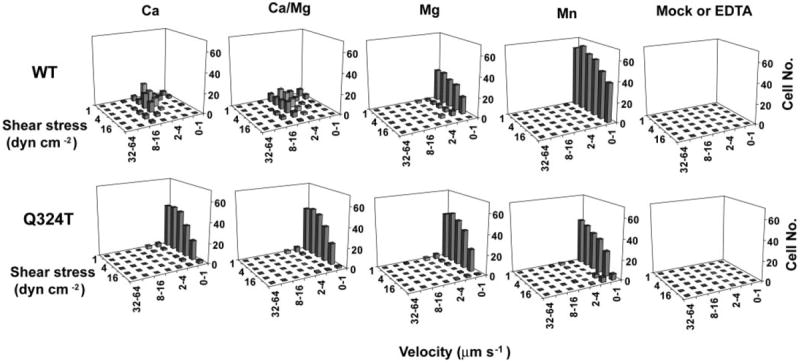

The adhesive behavior in shear flow of 293T α4β7 cell transfectants was characterized by allowing them to adhere to MAdCAM-1 in a parallel wall flow chamber, incrementally increasing the wall shear stress, and determining the velocity of the adherent cells. In 1 mm Ca2+, 293T transient transfectants expressing wild-type α4β7 rolled with increasing velocity as shear stress was increased (Fig. 2). By contrast, wild-type transfectants were firmly adherent in 1 mm Mg2+ (Fig. 2). In Mn2+, adhesiveness was more activated than in Mg2+ because more cells accumulated and fewer cells detached at the highest wall shear stress of 32 dynes/cm2. By contrast with wild type, the α4β7 Q324T glycan wedge mutant mediated firm adhesion regardless of the divalent cation present (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the accumulation efficiency and shear resistance of the wedge mutant was identical in Ca2+, Ca2+/Mg2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ and similar to that of the wild-type α4β7 293T transfectants in Mn2+. Thus, integrin α4β7 was constitutively activated by the glycan wedge introduced into the hybrid/I-like domain interface.

Fig. 2. Adhesion in shear flow of wild-type and glycan wedge mutant α4β7 cell transfectants on MAdCAM-1 substrates.

Cells were infused into the flow chamber in buffer containing 1 mm Ca2+, 1 mm Ca2+ + 1 mm Mg2+, 1 mm Mg2+, or 0.5 mm Mn2+. Cells transfected with α4 cDNA alone (Mock) or α4β7 transfectants treated with 5 mm EDTA did not accumulate on MAdCAM-1 substrates. Rolling velocities of individual cells were measured at a series of increasing wall shear stresses, and cells within a given velocity range were enumerated to give the population distribution. dyn, dynes.

Mutation of the α4 cleavage site residue Arg-558 abolishes α4 subunit cleavage and has no effect on α4β1 adhesion on fibronectin or VCAM-1 (29, 35). We tested the effect of the same mutation in α4β7 transfectants, and we found it to have no effect on adhesion in shear flow to MAdCAM-1 (data not shown).

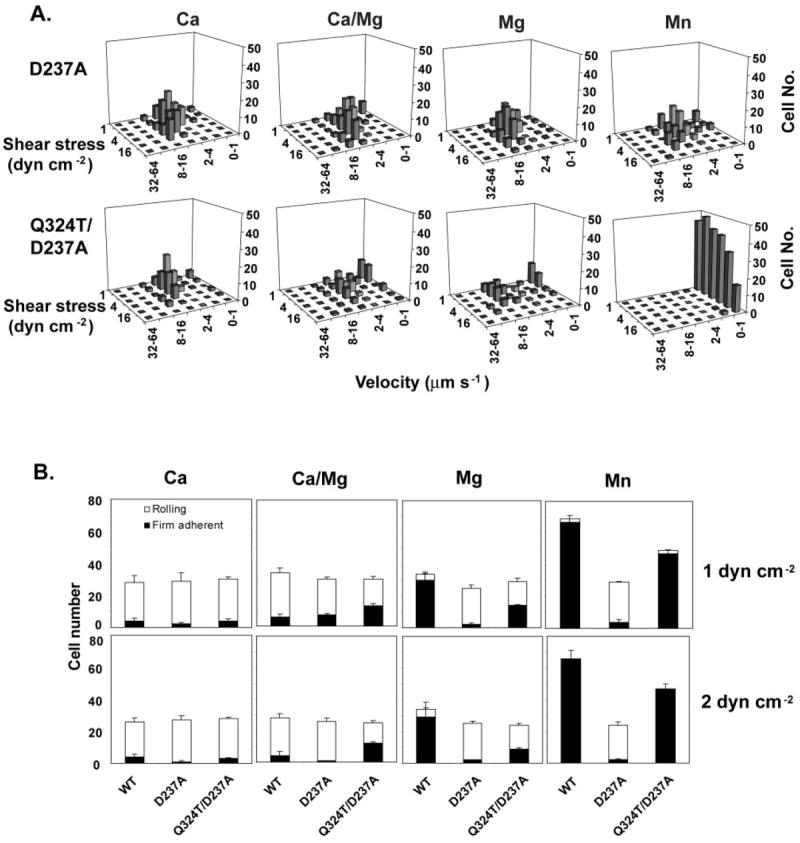

As described previously (15), mutation of LIMBS residues stabilizes integrin α4β7 in the low affinity state. For example, the LIMBS mutant D237A mediates rolling adhesion regardless of the divalent cations that are present (Fig. 3A). The wedge/LIMBS double mutant (Q324T/D237A) was expressed as well as the wedge mutant in 293T transfectants (Table I). Compared with the LIMBS mutation, the wedge/LIMBS double mutation reproducibly increased the number of firmly adherent cells at low shear (1 and 2 dynes cm−2) in Ca2+/Mg2+ and Mg2+ (Fig. 3). In Mn2+, the wedge/LIMBS mutant mediated firm adhesion, whereas the LIMBS mutant mediated rolling adhesion (Fig. 3). These data show that the LIMBS is required for full activation by the wedge mutation in Ca2+, Ca2+/Mg2+, and Mg2+ (Q324T/D237A mutant in Fig. 3A compared with Q324T mutant in Fig. 2). Furthermore, activation by Mn2+ of the double wedge/LIMBS Q324T/D237A mutant definitively establishes that the LIMBS is not required for activation by Mn2+.

Fig. 3. Interaction of glycan wedge and LIMBS mutations.

A, adhesive modality and resistance to detachment in shear flow of LIMBS (D237A) and wedge/LIMBS double mutant (Q324T/D237A) α4β7 293T transfectants on MAdCAM-1 substrates in the presence of 1 mm Ca2+, 1 mm Ca2+ + 1 mm Mg2+, 1 mm Mg2+, or 0.5 mm Mn2+. B, the number of rolling and firmly adherent α4β7 293T transient transfectants was measured in the same divalent cations as in A at a wall shear stress of 1 and 2 dynes cm−2. Data are ± S.D. (n = 3). dyn, dynes.

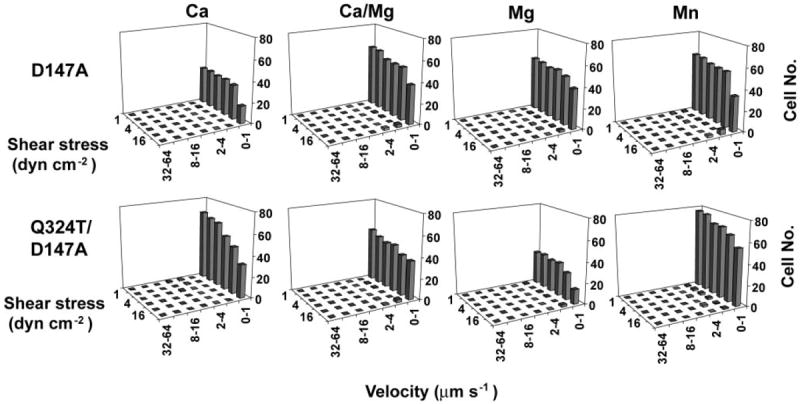

Increased Firm Adhesion by Double ADMIDAS/Wedge Mutant

Mutation of the negative regulatory ADMIDAS activates firm adhesion even in Ca2+ (15) (D147A mutant in Fig. 4 compared with wild type in Fig. 2). The double wedge/ADMIDAS Q324T/D147A mutant was somewhat less well expressed than the ADMIDAS D147A mutant (Table I). Nonetheless, the double Q324T/D147A mutant showed more firmly adherent cells in Ca2+ and Mn2+ than did the single D147A mutant (Fig. 4) or the single Q324T mutant (Fig. 2).

Fig. 4. Interaction of glycan wedge and ADMIDAS mutations.

Adhesive modality and resistance to detachment in shear flow of ADMIDAS (D147A) and double wedge/ADMIDAS (Q324T/D147A) mutant α4β7 transfectants on the MAdCAM-1 substrates in the presence of the indicated divalent cations. The divalent cation concentrations are the same as in Fig. 2. dyn, dynes.

DISCUSSION

Allosteric transition to the high affinity integrin headpiece conformation is proposed to involve rearrangement of the β I-like LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS (LMA) sites, downward displacement of the β I-like α7-helix that connects to the hybrid domain, and outward swing of the β hybrid domain (5, 7-9, 11, 12, 36). Outward swing of the hybrid domain has been demonstrated by electron micrographic studies of liganded αVβ3 and α5β1 integrins and crystal studies of liganded αIIbβ3 but not in an αVβ3 crystal structure in which crystal lattice and headpiece-leg interactions presumably prevented swing-out when a ligand was soaked into crystals (8, 18). Conversely, introduction of a glycan wedge into the β1 and β3 subunits has been demonstrated to induce high affinity for ligand by α5β1 and αIIbβ3 integrins (9). Both of these integrins recognize ligands with RGD sequences. We have extended these results here to the α4β7 integrin, which does not recognize RGD in its ligands and which mediates both rolling and firm adhesion. In α4β7, the glycan wedge converted rolling adhesion in Ca2+ and Ca2+/Mg2+ to firm adhesion, demonstrating that stabilizing the open conformation at the I-like/hybrid domain interface is sufficient to stabilize high affinity firm adhesion.

Furthermore, we examined here for the first time the interplay between the LMA metal binding sites at the ligand-binding interface on the “top” of the β I-like domain and the interface with the hybrid domain on the opposite, “bottom” face of the I-like domain. We asked whether one of these two interfaces would dominate regulation of rolling or firm adhesion, or whether there would be mutuality in which mutations in each of these interfaces influenced the equilibrium between rolling and firm adhesion. The results demonstrate the latter. That is, stabilization of rolling adhesion by LIMBS mutation was partially counteracted by the wedge mutation in Ca2+/Mg2+ and Mg2+ and fully counteracted in Mn2+, where firm adhesion occurred. Conversely, stabilization of firm adhesion by the wedge mutation was fully counteracted by the LIMBS mutation in Ca2+, where rolling occurred, and largely counteracted in Ca2+/Mg2+ and Mg2+. Therefore, the equilibrium at the LMA sites strongly influences that at the β I-like/hybrid domain interface and vice versa, and changes in equilibrium at one site can counterbalance those at the other. The combined effects of the ADMIDAS and wedge mutations also demonstrated additive effects at the LMA sites and I-like/hybrid interface because changes at both of these sites stabilized firm adhesion more strongly than changes at either alone.

Another notable finding of these studies is that Mn2+ can still activate firm adhesion when the LIMBS is mutated. Previously, the LIMBS and ADMIDAS were found to be positive and negative regulatory sites, respectively, and positive regulation by low Ca2+ concentrations was found to be intact when the ADMIDAS was mutated (15). This, together with structural considerations, suggested that negative regulation by high Ca2+ concentrations was effected at the ADMIDAS. Scatchard plots showed competitive rather than noncompetitive inhibition by Ca2+ of stimulation by Mn2+, suggesting that the ADMIDAS was also the stimulatory site for Mn2+. However, it was not possible to confirm the role of the ADMIDAS in stimulation of firm adhesion by Mn2+ because rolling adhesion occurred in LIMBS mutants even in Mn2+. By contrast, in the double LIMBS/wedge mutant, the equilibrium between rolling and firm adhesion is not far from that in wild type, and it is regulated by divalent cations. Mn2+ was found to fully activate firm adhesion by the LIMBS/wedge mutant, showing that the LIMBS is not required for regulation by Mn2+ and providing strong support for the previous conclusion that the ADMIDAS is the site for activation by Mn2+.

Although much progress has been made recently in defining different integrin conformational states, questions remain about how signals are transduced from the cytoplasm to the ligand binding site and whether intermediate conformational states have intermediate affinity for ligand. It appears that to mediate rolling adhesion, integrins must be in one of the extended conformations rather than in the bent conformation (15, 37). The extended conformation with the closed headpiece is an intermediate in the conformational pathway between the bent conformation, which contains a closed headpiece, and the extended conformation with the open headpiece (5). The current study demonstrates that stabilization of the open headpiece by a glycan wedge at the β I-like/hybrid interface is sufficient to convert low affinity rolling adhesion to high affinity firm adhesion. It appears that the glycan wedge converts the extended conformation with the closed headpiece to the extended conformation with the open headpiece. Therefore, this study strongly suggests that within the extended integrin conformation, conversion of the closed to the open headpiece is sufficient to convert rolling adhesion to firm adhesion. In an intact integrin, marked separation in the plane of the membrane of the transmembrane domains of the integrin α and β subunits would also stabilize the open headpiece and therefore may be the mechanism for converting rolling adhesion to firm adhesion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael J. Briskin for providing the human MAdCAM-1/Fc.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HL48675.

The abbreviations used are: mAb, monoclonal antibody; MIDAS, metal ion-dependent adhesion site; LIMBS, ligand-induced metal binding site; ADMIDAS, adjacent to MIDAS; LMA, LIMBS, MIDAS, and ADMIDAS; MAdCAM-1, mucosal cell adhesion molecule-1.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takagi J, Springer TA. Immunol Rev. 2002;186:141–163. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2002.18613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M, Carman CV, Springer TA. Science. 2003;301:1720–1725. doi: 10.1126/science.1084174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Cell. 2002;110:599–611. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vinogradova O, Velyvis A, Velyviene A, Hu B, Haas TA, Plow EF, Qin J. Cell. 2002;110:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00906-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takagi J, Strokovich K, Springer TA, Walz T. EMBO J. 2003;22:4607–4615. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao T, Takagi J, Wang J-h, Coller BS, Springer TA. 2004;432:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo B-H, Springer TA, Takagi J. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2403–2408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0438060100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo B-H, Strokovich K, Walz T, Springer TA, Takagi J. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27466–27471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mould AP, Barton SJ, Askari JA, McEwan PA, Buckley PA, Craig SE, Humphries MJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:17028–17035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213139200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luo B-H, Takagi J, Springer TA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10215–10221. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312732200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang W, Shimaoka M, Chen JF, Springer TA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2333–2338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Springer TA, Wang J-h. In: Cell Surface Receptors. Garcia KC, editor. Elsevier; San Diego, CA: 2004. pp. 29–63. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JF, Salas A, Springer TA. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/nsb1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Chateau M, Chen S, Salas A, Springer TA. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13972–13979. doi: 10.1021/bi011582f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berlin C, Bargatze RF, von Andrian UH, Szabo MC, Hasslen SR, Nelson RD, Berg EL, Erlandsen SL, Butcher EC. Cell. 1995;80:413–422. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90491-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, Frech M, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Science. 2002;296:151–155. doi: 10.1126/science.1069040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong J-P, Stehle T, Diefenbach B, Zhang R, Dunker R, Scott DL, Joachimiak A, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. Science. 2001;294:339–345. doi: 10.1126/science.1064535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazarovits AI, Moscicki RA, Kurnick JT, Camerini D, Bhan AK, Baird LG, Erikson M, Colvin RB. J Immunol. 1984;133:1857–1862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schweighoffer T, Tanaka Y, Tidswell M, Erle DJ, Horgan KJ, Luce GE, Lazarovits AI, Buck D, Shaw S. J Immunol. 1993;151:717–729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tidswell M, Pachynski R, Wu SW, Qiu S-Q, Dunham E, Cochran N, Briskin MJ, Kilshaw PJ, Lazarovits AI, Andrew DP, Butcher EC, Yednock TA, Erle DJ. J Immunol. 1997;159:1497–1505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu C, Oxvig C, Springer TA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15138–15147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.24.15138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo B-H, Springer TA, Takagi J. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:776–786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lawrence MB, Springer TA. Cell. 1991;65:859–873. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90393-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salas A, Shimaoka M, Chen S, Carman CV, Springer TA. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50255–50262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209822200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang J-S, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Acta Crystallogr Sect D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holzmann B, Weissman IL. EMBO J. 1989;8:1735–1741. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teixido J, Parker CM, Kassner PD, Hemler ME. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:1786–1791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parker CM, Pujades C, Brenner MB, Hemler ME. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7028–7035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hemler ME, Elices MJ, Parker C, Takada Y. Immunol Rev. 1990;114:45–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1990.tb00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez-Madrid F, De Landazuri MO, Morago G, Cebrian M, Acevedo A, Bernabeu C. Eur J Immunol. 1986;16:1343–1349. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830161106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McIntyre BW, Evans EL, Bednarczyk JL. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13745–13750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bednarczyk JL, Szabo MC, McIntyre BW. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25274–25281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bergeron E, Basak A, Decroly E, Seidah NG. Biochem J. 2003;373:475–484. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mould AP, Symonds EJ, Buckley PA, Grossmann JG, McEwan PA, Barton SJ, Askari JA, Craig SE, Bella J, Humphries MJ. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:39993–39999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salas A, Shimaoka M, Kogan AN, Harwood C, von Andrian UH, Springer TA. Immunity. 2004;20:393–406. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]