Abstract

HIV/AIDS has been described as a household shock distinct from others faced by rural households. This study examines this characterisation by analysing the impact of an adult HIV/AIDS-related death on household food security, compared with households experiencing either no mortality or a sudden non-HIV/AIDS adult death. The research is based in the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance Site in rural South Africa, and focuses on a sample of 290 households stratified by experience of a recent prime-age adult death. HIV/AIDS-related mortality was associated with reduced household food security. However, much of this negative association also characterised households experiencing a non-HIV/AIDS mortality. In addition, other household characteristics, especially socioeconomic status, were strong determinants of food security regardless of mortality experience. We therefore recommend that development policy and interventions aimed at enhancing food security target vulnerable households broadly, rather than solely targeting those directly affected by HIV/AIDS mortality.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, food security, household shock, rural livelihoods

1. Introduction

The trio of HIV/AIDS, poverty and food insecurity is a pressing social and development problem facing southern Africa (Lemke, 2005). The figures for South Africa are alarming: roughly one in six prime-age adults is living with HIV and AIDS (Shisana et al., 2009), one in five South African households is chronically poor (Aliber, 2003), and one in three households is vulnerable to food insecurity (StatsSA, 2000). Overlaid, these statistics paint a stark picture, particularly for rural communities in the former homelands, where adult mortality due to HIV/AIDS has increased dramatically over the last decade (Hosegood et al., 2004; Kahn et al., 2007a). The former homelands are also where the majority of the nation's poor and food insecure households live (Rose & Charlton, 2002; Aliber, 2003). The research presented here brings together these three problems by investigating the relationship between adult HIV/AIDS-related mortality and household food insecurity in a context of poverty in a rural region of Mpumalanga Province, South Africa.

2. HIV/AIDS, rural livelihoods and food security

HIV/AIDS has been characterised as a household shock distinct from others faced by rural households, such as drought, because of its long-term nature and impacts on household labour and production resources (Barnett & Blaikie, 1992; Baylies, 2002). HIV infection and AIDS mortality are disproportionately high among the economically active age groups, with far-reaching consequences for rural households whose livelihoods are dependent on agricultural production and remittances from employed migrant family members (Baylies, 2002; Hargreaves & Pronyk, 2003; Gregson et al., 2007). Poor rural households that have lost a household head are particularly slow to recover from the economic impacts of an HIV/AIDS-related death (Yamano & Jayne, 2004). The substantial financial strain often placed on households by an HIV/AIDS-related illness or death may mean they have to resort to coping strategies, such as rationing food, divesting themselves of family assets, and spending savings to compensate for income loss. Some authors caution against using the term ‘coping strategies’, since responses such as these further undermine livelihood resilience and do not represent a successful dealing with adversity in the longer term, especially if these strategies become permanent (Loevinsohn & Gillespie, 2003; Marais, 2005).

The livelihood impacts of HIV/AIDS have important implications for food security (Haddad & Gillespie, 2001; Baylies, 2002; Gillespie & Kadiyala, 2005). Besides affecting the household's income and ability to buy food, adult morbidity and mortality also significantly affect household human capital needed for producing food in rural communities reliant on small-scale agriculture (Barnett & Blaikie, 1992; Haddad & Gillespie, 2001; Baylies, 2002; Jackson, 2002). Even in South Africa, where rural households are less dependent on agriculture than in the rest of the continent, these households remain particularly vulnerable to the multiple impacts of the illness and death of a household member (Hargreaves & Pronyk, 2003). Clover (2003:10) aptly states that ‘All dimensions of food security – availability, stability, access and use of food – are affected where the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is high’. De Waal and Whiteside (2003) hypothesise that the HIV/AIDS pandemic has, in fact, changed the profile of vulnerability to hunger in southern Africa, yielding a ‘new variant famine’ which may be independent of the pressures caused by drought. However, data on the links between HIV/AIDS and acute food insecurity are lacking (De Waal & Tumushabe, 2003).

Few studies have explicitly investigated the impacts of HIV/AIDS on food security in southern Africa, despite the region being commonly referred to as the ‘epicentre’ of the global HIV/AIDS pandemic. Nevertheless, the small but growing body of scholarship suggests some general patterns. A study in rural Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe showed that households affected by HIV/AIDS were more vulnerable to food insecurity, but that factors such as the role of the infected person and the household's demographic and socioeconomic status (SES) shaped the impact (SADC FANR, 2003). Poor households were the most severely affected by the mortality. In KwaZulu-Natal Province in South Africa, households’ experience of food shortages was also intensified by their experience of an adult HIV/AIDS-related death, although dietary diversity was unaffected (Kaschula, 2008). In our previous research in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa, we found that households that had experienced a prime-age adult death were more likely than unaffected households to have experienced hunger, especially if the household was poor and the deceased was a male (Hunter et al., 2007).

While these studies provide evidence to support the ‘new variant famine’ hypothesis, caution should be exercised when making such an interpretation. As in most such food security studies, household proxy measures for HIV/AIDS, such as chronic illness or death of a prime-age adult, were used. More precise identification of the form of household mortality experience is needed for conclusive results on the unique nature of AIDS impacts, but stigma and ethical considerations make such research at the household level difficult.

The study reported here therefore makes an important contribution because we draw on mortality data, which include cause of death, to model the relationship between HIV/AIDS-related adult mortality and household food security in a rural region of South Africa. We hypothesised that households that had experienced an HIV/AIDS-related prime-age adult death would be less food secure than comparable households that had not experienced a death over the same time period. We further contrasted HIV/AIDS-affected households with those experiencing a recent sudden prime-age adult death not due to HIV/AIDS in order to explore the uniqueness of HIV/AIDS as a household shock. Given the dearth of empirical work on the unique nature of AIDS mortality, we do not offer a hypothesis for this second analytical section.

3. Methods

3.1. Study site

This study was conducted in the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System (AHDSS) site which is operated by the Medical Research Council/ University of the Witwatersrand Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (abbreviated hereafter as the Agincourt Unit). The site, named after one of the local villages, is situated in the northeast of South Africa, in the rural municipality of Bushbuckridge, Mpumalanga Province. It encompasses 25 villages, over 14000 households and 84000 people. Village population sizes range from 480 to 6834. Approximately a quarter of the population are former Mozambican refugees, most of whom fled to South Africa during the civil war in Mozambique in the 1980s.

The area is typical of rural communities across South Africa, being characterised by poverty and high human densities. Few households are able to support themselves on agriculture alone, primarily because of the shortage of land and declining interest in agriculture as a result of the previous government's forced relocation and separate development policies for black South Africans (Hargreaves & Pronyk, 2003). Because local employment opportunities are poor, a large proportion of adults are migrant labourers, working on commercial farms and in towns and cities across the country (Collinson et al., 2007). A significant proportion of households depend on the state pension of an elderly resident as the only reliable source of household income.

HIV prevalence in Mpumalanga Province is 15% (Shisana et al., 2009), and HIV/AIDS and TB (often associated with HIV) are the leading causes of death among adults between the ages of 15 and 49 in the study site (Kahn et al., 1999). Furthermore, mortality among young adults increased fivefold in the study site over the decade from 1992–1993 to 2002–2003, largely because of the emerging HIV/AIDS pandemic (Kahn et al., 2007a).

3.2. Data sources

Two data sources were used for this study:

Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System (AHDSS): Data on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of households and individuals were provided by the Agincourt Unit. Since 1992, the unit has collected census data annually from all households in the AHDSS site. The resulting data are extremely rich in sociodemographic detail, allowing identification of key household characteristics (e.g. size, male or female headship, age composition, SES). The AHDSS also provided data on individual mortality – crucial for our study design, which focused on differentiating between households with different types of adult mortality experience.

Quantitative survey: We surveyed 290 households with differing prime-age adult mortality experience (details below) to collect data on household livelihoods and food security. The survey instrument was informed by central literature, as well as the investigators’ previous experience in the Agincourt field site. Household food security was assessed using accepted proxy indicators and methodologies (see Hoddinott, 1999, for a useful comparison of the most commonly used methods and Hendriks, 2005, for a useful overview in the South African context). Our choice of methods, resulting from trade-offs between time, cost, accuracy and the expertise required, was as follows: i) a dietary diversity index for 99 food items and 10 food groups, recording whether the item was eaten at least once in the last week, month, year, or not at all (see Hoddinott & Yohannes, 2002; Swindale & Bilinsky, 2005; ii) a record of household experience of hunger and access to food, such as the number of times in the last 30 days the household worried about or ran out of food (see Household Food Insecurity Scale [FANTA, 2004] or the Food Access Survey Tool [Coates et al., 2003]); and iii) a list of coping strategies,1 based on the frequency of short-term responses to food shortages, such as asking neighbours for food or skipping meals (see Maxwell 1996; Maxwell et al., 1999). These three methods were adapted for local conditions using insights gained from three focus groups with local women. The focus group participants helped to develop lists of foods eaten locally, as well as typical coping strategies used when facing food shortages.

The study's cross-sectional nature posed a major analytical challenge since temporal variation in household food security could not be explicitly tracked. For this reason, all households in the sample were asked about recent changes in their food security, and those with recent adult mortality experience were also asked carefully phrased questions about changes in food security specifically as a result of the household member's death.

Survey data were collected from 290 households. Mortality data are described below in Section 3.3.1. A stratified random sample of households was drawn from the Agincourt AHDSS database across the three mortality strata as follows: (i) HIV mortality: experienced a prime-age adult death due to HIV/AIDS in the two years prior to the survey, (ii) non-HIV mortality: experienced a sudden prime-age adult death, unrelated to HIV/AIDS, in the two years prior to the survey, and (iii) no mortality: experienced no death of a prime-age adult in the two years prior to the survey. By comparing households with HIV and sudden non-HIV deaths, we aimed to indirectly explore the potentially unique impacts of HIV mortality, which often includes a preceding long period of illness.2

Households sampled from the database were located in the field using their unique identifier number on digital aerial photographs used by the Agincourt Unit in their annual census. The survey was conducted by experienced local fieldworkers from the unit. The respondent was typically the female primarily responsible for food acquisition and preparation and acquisition of woodland resources. The survey was conducted in May and June 2006, using the dominant local language, Xitsonga.

3.3. Incorporated variables

3.3.1. Household mortality experience

Since our primary analytical variable was household mortality experience, we made use of the Agincourt Unit's demographic surveillance data to identify households that had experienced the death of a prime-age adult member during the past two years. Cause of death was obtained from the AHDSS as ascertained through ‘verbal autopsies’ undertaken for each mortality experience in the study site (Kahn et al., 2000; Kahn et al., 2007b). A verbal autopsy is conducted as follows. A trained fieldworker interviews the closest available caregiver of the deceased, using a structured questionnaire. The interview is then independently assessed by two medical doctors who individually assign a probable cause of death. If these diagnoses correspond, the proposed cause ofdeath is accepted. If they differ, the two doctors discuss the case in an effort to reach consensus. If no agreement is reached, the interview is sent to a third doctor who has not seen the initial two diagnoses. With the three assessments, agreement between two is accepted as the most probable cause of death. If consensus remains unattainable, cause of death is labelled ‘ill-defined’. This tool was validated locally using hospital records in the 1990s (Kahn et al., 2000) and has recently (2001–2005) been re-validated for HIV/AIDS assessment (Kahn et al., 2007b). The data from the verbal autopsies thus allow classification of HIV/AIDS-related deaths (which are not reflected on death certificates in South Africa) as well as other mortality causes.

This study focuses on mortality of prime-age adults aged 15 to 49, as this age range represents the period of largest economic contribution to the household, as well as being the age range of those most susceptible to HIV/AIDS. Deaths occurring in this age group in the total census population over the two years prior to the survey were classified as either HIV/AIDS-related (hereafter ‘HIV death’) or non-HIV/AIDS-related (hereafter ‘non-HIV death’). Non-HIV deaths were further classified as ‘sudden’ (e.g. heart attack, motor vehicle accident) or ‘slow’ (e.g. cancer). We used these mortality classifications to generate the strata from which the sample was drawn.

3.3.2. Additional household data

Linking with a health and demographic surveillance system is a particular strength of this study, because it enabled a) drawing of a random stratified sample from a known population, b) incorporation of actual cause of death, rather than AIDS proxies, and c) inclusion of other household data, such as size and SES, in our analyses. SES, based on a ‘wealth ranking’, was obtained for households from the Agincourt Unit's database. Wealth ranking is determined by household ownership of assets (e.g. appliances) and access to services and amenities appropriate for the setting (e.g. a water tap in the yard). Household SES score is the factor score obtained from principle components analysis of the wealth ranking variables. The factor analysis reorganises the 34 ordinal variables into independent factors that each have a certain weight (factor score). The weight of the first factor (principal component) contains the bulk of the variance of the whole dataset. The SES scores are mathematically standardised and centred on a mean of zero. In our dataset, scores ranged from −5.87 to 6.43. All households are also ranked in the order of the first factor score and then categorised into SES quintiles.

3.4. Analytical approach

Responses for household experience of hunger and coping strategies were expressed as binary outcomes (yes/no). Household consumption of food items was expressed as 1) an ordinal frequency scale (not at all, at least once in the last week, month, year) and 2) as a binary response for each food category (e.g. cereals) (yes/no). We calculated the weekly, monthly and annual dietary diversity by summing the numbers of food items consumed by the household over each of these periods. Weekly diversity of food groups (meat, fruit, vegetables, pulses, starches, nuts, sugar, dairy, eggs and fat/oil) was calculated by summing the number of food groups for which at least one item had been eaten by the household in the last seven days.

Several steps were taken to calculate a dietary diversity score as a continuous variable reflecting both diversity and frequency of particular foods and food groups. First, frequency per food item was converted to a weekly fraction as follows:

-

1)

At least once in the last 7 days (1 week): 1/1 = 1

-

2)

At least once in the last 30 days (30 days/7 days = 4.29 weeks): 1/4.29 = 0.23

-

3)

At least once in the last 12 months (365 days/7 days = 52.14 weeks): 1/52.14 = 0.02

-

4)

More than 12 months ago/never: = 0.

These values were then summed for all 99 food items to give an absolute dietary diversity score out of 99, which incorporated both the range of food items eaten and the frequency of consumption. This was then converted to a proportional dietary diversity score by dividing the absolute value by the maximum possible value (99). The score thus represents the household composite dietary diversity over a year relative to the maximum possible (all foods every week).

Bivariate associations were explored between household characteristics, food security and adult mortality experience using correlation analysis, linear and logistic regression analysis, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey post hoc test. Multivariate models, such as analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) with Tukey post hoc test and multivariate logistic regression analysis, were estimated to further control for household size and socioeconomic status. The software used for statistical analysis was STATA 10.0 for Linux.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of households and the deceased household member

We start with an examination of the variation in household size (permanent members) and SES across mortality strata. We also compare the time since the adult death, the total number of recent deaths in the household, and the role the deceased had played in household food provisioning between the two mortality strata.

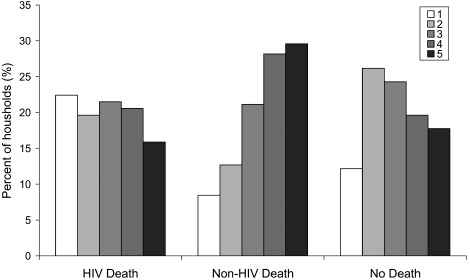

The mean number of permanent household members averaged five and did not differ significantly across the three strata (see Table 1). For SES, despite high variability within strata, households affected by a sudden non-HIV adult death scored significantly higher on the assets index than HIV-affected or non-mortality households. This was true both before (2003) and after (2005) the death in question. In 2005, non-HIV mortality households were predominantly in the two highest SES quintiles, while HIV-affected households were relatively evenly spread across quintiles (see Figure 1). Nearly half of the households with no recent deaths were in the second and middle quintiles. It is important to note that mean SES score remained unchanged for HIV-affected households over the two years spanning the death. Mean SES score decreased slightly for non-HIV mortality households and increased for control households over this period, but these differences were not significant at the 5% level. SES score and household size were positively correlated (correlation coefficient = 0.19, p < 0.05).

Table 1:

Mean household characteristics and relative frequency of the roles of the deceased in household food provisioning, by recent household mortality experience

| Variable | HIV death | Non-HIV death | No death |

|---|---|---|---|

| Household characteristics | |||

| Household size | 5.0 (3.2)a | 5.5 (2.9)a | 4.5 (2.4)a |

| SES score: 2003 | −0.24 (2.38)a | 1.09 (2.16)b | 0.04 (2.20)a |

| SES score: 2005 | −0.24 (2.17)a | 0.91 (2.12)b | 0.14 (1.88)a |

| Mortality variables | |||

| Time since death (months) | 18.5 (6.6)a | 18.9 (5.2)a | – |

| Total deaths over sample period | 1.7 (1.0)a | 1.5 (0.6)a | – |

| Role of the deceased in food provisioning | |||

| Contributed income | 59.6% | 70.8% | – |

| Tended a food garden and/ or field | 59.6% | 64.6% | – |

| Collected natural resources | 51.9% | 46.2% | – |

Note: Standard deviation in brackets. Values which do not share a common superscript letter within a row are significantly different (p < 0.05) and highlighted in bold.

Figure 1.

Frequency profile of household SES quintiles (1 = poorest, 5 = wealthiest) in 2005, by recent household mortality experience (n = 290)

Among mortality-affected households, neither time since death nor total number of deaths experienced differed significantly between the two strata (Table 1). Regarding the role of the deceased in the household economy and/or food provisioning, a slightly higher proportion of individuals who had died of sudden non-HIV causes had contributed income to the household or been involved in growing food crops (Table 1). Conversely, more household members who had died from HIV-related causes had collected natural resources, including wild foods.

4.2. Household characteristics and food security

Before assessing the effect of an adult HIV-related death on household food security, it is important to examine the potentially complicating influence of other household factors on food security. We focused on household size and SES. The only significant influence of household size on food security was an increase in the number of food groups included in the diet where there was an increase in the number of permanent members (beta coefficient = 0.18, p <.0.05, R2 = 0.03). As would be expected, SES had a more pervasive positive influence on food security (Table 2). All measures of dietary diversity increased with SES score, while the likelihood of going hungry or skipping meals decreased with SES score (Table 2).

Table 2:

Summary of significant linear and logistic regression models for measures of food security against household size and SES score

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Model parameters |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | p value | R2 | ||

| Dietary diversity | ||||

| Food groups in last week | Household size | 0.18 | <0.05 | 0.03 |

| SES | 0.24 | <0.001 | 0.06 | |

| Total foods in last week | SES | 0.34 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Total foods in last month | SES | 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.12 |

| Total foods in last year | SES | 0.27 | <0.001 | 0.08 |

| Prop. dietary diversity | SES | 0.35 | <0.001 | 0.13 |

| Experience of hunger |

Odds ratio |

p value |

Pseudo R2 |

|

| Went hungry | SES | 0.86 | <0.05 | 0.02 |

| Coping strategies | ||||

| Skipped meals | SES | 0.83 | <0.01 | 0.03 |

4.3. Adult mortality and household food security

4.3.1. Dietary diversity

When it came to the effect of an adult death on household food security, mean dietary diversity was significantly lower in HIV-affected households than in non-mortality households for three of the five included measures (Table 3). The mean number of food items eaten by HIV-affected households in the last year was also significantly lower than that of households which experienced a sudden non-HIV mortality. However, only the mean total number of foods eaten in the last year remained significantly lower among HIV-affected households after controlling for household size, and none of the mean scores differed significantly between mortality strata when controlling for SES (adjusted means in Table 3). Nevertheless, there were particular foods no longer eaten by some households specifically because their breadwinner had died, regardless of cause of death. The impact of the loss of a breadwinner in this regard, relative to that of poverty in general, was most pronounced for perceived ‘luxury’ items such as butter or margarine, cheese, rice and beef.

Table 3:

Raw and adjusted mean dietary diversity (controlling for household size and SES score), by household mortality experience

| Parameter | Food groups in last week | Total foods in last week | Total foods in last month | Total foods in last year | Prop. dietary diversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 4–10 | 5–50 | 10–64 | 36–86 | 0.07–0.52 |

| Raw means | |||||

| HIV death | 7.8a | 21.9a | 33.2a | 57.9a | 0.25a |

| Non-HIV death | 7.9a | 24.2ab | 35.7a | 61.7b | 0.28ab |

| No death | 7.8a | 24.9b | 36.1a | 61.5b | 0.28b |

| Adjusted means, controlling for household size | |||||

| HIV death | 7.7a | 21.9a | 33.2a | 57.8a | 0.26a |

| Non-HIV death | 7.9a | 24.1a | 35.5a | 61.7a | 0.27a |

| No death | 7.8a | 25.0a | 36.2a | 61.5a | 0.28a |

| Adjusted means, controlling for socioeconomic (SES) score | |||||

| HIV death | 7.8a | 22.6a | 33.9a | 58.5a | 0.25a |

| Non-HIV death | 7.9a | 23.3a | 34.5a | 60.8a | 0.27a |

| No death | 7.9a | 24.9a | 36.1a | 61.5a | 0.28a |

Note: Means that do not share common superscripts within a comparison are significantly different (p < 0.05) and are highlighted in bold.

4.3.2. Experience of hunger

A total of 26% of all households surveyed had experienced severe food shortage (worried about food, run out of food and gone hungry simultaneously) in the last 30 days. HIV-affected households were significantly more likely than non-mortality households to have gone hungry or had multiple experiences of hunger in the last 30 days (Table 4).

Table 4:

Logistic regression models comparing the likelihood of experience of hunger in HIV-impacted households with households experiencing a non-HIV death or no death (1), and controlling for household size and SES score (2)

| Parameter | Worried about food |

Ran out of food |

Went hungry |

All three experiences |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | |

| Odds ratios | ||||||||

| Non-HIV death | 1.54 | 1.79 | 1.80 | 2.26 | 1.20 | 1.56 | 1.33 | 1.65 |

| No death | 0.62 | 0.69 | 0.78 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 0.59 | 0.42 | 0.50 |

| Household size | – | 1.05 | – | 1.02 | – | 1.02 | – | 1.04 |

| SES | – | 0.89 | – | 0.86 | – | 0.84 | – | 0.87 |

| Model | ||||||||

| LR chi2 | 8.86 | 12.47 | 7.46 | 13.61 | 8.14 | 14.20 | 11.96 | 15.06 |

| p value | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

Note: Statistically significant odds ratios are highlighted in bold (p < 0.05).

However, they were no more likely to experience hunger than households with a non-HIV mortality (before controlling for SES). Furthermore, non-HIV mortality households were also significantly more likely than non-mortality households to have experienced hunger for all four measurements (results not shown). However, the patterns changed when including household size and SES score in the multivariate models. Household size had no effect, but increasing SES significantly decreased the likelihood of running out of food, going hungry and multiple experiences of hunger in the multivariate models. When controlling for SES, households experiencing a non-HIV death were significantly more likely than HIV-affected households to have run out of food over the last month, while HIV-affected households were no longer more likely than control households to have gone hungry. However, HIV-affected households were still significantly more likely to have had multiple experiences of hunger than non-mortality households, even when controlling for SES. Households were increasingly likely to have worried about food in the last month where there was an increase in the total number of deaths experienced by the household in the last two years, regardless of the cause of death of the deceased member (odds ratio = 1.27, p < 0.05).

4.3.3. Coping strategies

Of the 290 households surveyed, 13% had engaged in all three coping strategies related to food shortages (eaten foods they did not enjoy, asked neighbours for food, and skipped meals for a day) at least once in the last seven days. HIV-affected households were significantly more likely than non-mortality households to engage in eating unpleasant foods, skipping meals, and multiple strategies (Table 5). The same patterns held for non-HIV mortality households (not shown). Households from both mortality strata were equally likely to engage in coping strategies. There was a significant negative association between the likelihood of household members skipping meals and household SES score, and controlling for SES in the multivariate models eliminated the mortality influence on coping strategies. Household size had no influence. Among mortality-affected households, the odds of eating unpleasant foods were greater for those experiencing more than one adult death in the prior two years, regardless of mortality stratum (odds ratio = 1.33, p < 0.05).

Table 5:

Logistic regression models comparing the likelihood of food-related coping strategies in HIV-impacted households with households experiencing a non-HIV death or no death (1), and also controlling for household size and SES score (2)

| Parameter | Ate unpleasant food |

Asked neighbours for food |

Skipped meals |

All three strategies |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | (1) | (2) | |

| Odds ratios | ||||||||

| Non-HIV death | 1.47 | 1.69 | 1.47 | 1.66 | 1.13 | 1.56 | 0.87 | 1.04 |

| No death | 0.56∗ | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.86 | 0.49 | 0.62 | 0.37 | 0.45 |

| Household size | 1.04 | 1.08 | 1.07 | 1.11 | ||||

| SES | - | 0.92 | - | 0.90 | - | 0.79 | - | 0.85 |

| Model | ||||||||

| LR chi2 | 9.43 | 11.55 | 3.56 | 7.29 | 6.23 | 15.99 | 5.82 | 10.50 |

| p value | <0.01 | <0.05 | 0.169 | 0.121 | <0.05 | <0.01 | 0.055 | <0.05 |

Note: Statistically significant odds ratios are highlighted in bold (p < 0.05). ∗p = 0.05.

5. Discussion and recommendations

The AIDS pandemic continues to shape the landscape of coping strategies across rural sub-Saharan Africa. Here, we offer empirical estimates of the association between HIV/AIDS-related adult mortality and household food security. Overall levels of food insecurity observed in the study were alarming, but were not as high as those suggested for the national level by Statistics South Africa (StatsSA, 2000). Against this backdrop, our results suggest that mortality-affected households are often less food secure than non-mortality households. However, HIV/AIDS-related mortality does not necessarily appear unique when compared with the household impacts of mortality from other causes. We also found that some of the HIV/AIDS impacts, and indeed mortality effects in general, disappeared when controlling for household characteristics, especially SES, because of positive associations between SES and food security.

Our results clearly demonstrated that an adult death due to HIV/AIDS had a greater negative impact on household dietary diversity than a sudden non-HIV adult death. Adult mortality also had a negative effect on household food sufficiency (even when controlling for SES). This is in agreement with Kaschula (2008), who found lower food quantity security scores in AIDS-afflicted households. However, we showed that this impact was not unique to households where the cause of death had been HIV-related. If anything, it was households affected by a non-HIV death that were more likely to experience food shortages than HIV-affected households, after controlling for SES. Similarly, HIV-affected households were no more likely than those affected by a non-HIV death to engage in food-related coping strategies. This challenges the notion of the distinctness of HIV/AIDS as a household shock, at least in relation to food security (Baylies, 2002; De Waal & Whiteside, 2003).

There are a number for possible explanations for these observations. First, the deceased was more likely to have been a breadwinner in wealthier households affected by a non-HIV death. The person's loss would therefore have had a severe impact on the household's ability to buy food. A common household response to the increased financial burden associated with the illness and then death of a household member due to HIV is to reduce expenditure on food (Gillespie & Kadiyala, 2005). The impact of the death on household food security, especially in terms of having sufficient food, would therefore be expected to be greater for such households, which are more reliant on cash for purchasing food. A second possibility is that households afflicted by an HIV/AIDS death had time during the period of illness to adapt, finding other ways of meeting their food needs, such as by relying on social networks or engaging in additional economic activities to supplement the household income. By contrast, those affected by a sudden non-HIV death were thrust into a state of crisis unexpectedly. That is not to say that HIV-affected households have necessarily recovered or coped better. HIV-affected households which are in distress often respond by adopting unsustainable livelihood strategies, such as selling off productive assets, indicating that they are in fact not coping in the longer term (Loevinsohn & Gillespie, 2003; Masanjala, 2007). This points to a third possibility: the period of observation after the adult death (maximum of two years) was potentially too short to accurately reflect the impacts of an HIV/AIDS mortality on a household, given the long-wave nature of HIV/AIDS as a household shock (Barnett & Blaikie, 1992; Gillespie & Kadiyala, 2005). This possibility is being further investigated in follow-up research.

Although we did observe mortality impacts on household food security, it appears that poverty is central in shaping food insecurity, since poor households, regardless of recent adult mortality experience, were similarly vulnerable. Our observed lack of evidence of an impact of an HIV/AIDS death on dietary diversity, after controlling for SES, concurs with findings by Kaschula (2008) in her study in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. The modest dampening effect of household size on the impact of adult mortality on dietary diversity is also probably due to the fact that this household attribute co-varied with SES. In addition, the negative effect of an HIV/AIDS death on household food security disappeared for all measures of food sufficiency and coping strategies after controlling for SES, the only exception being our most severe measure of food insufficiency. These observations are very important, and echo the findings of other studies such as Peters et al. (2008) which demonstrate that much of the observed hardship associated with HIV/AIDS is essentially due to pre-existing levels of poverty-related vulnerability. Similarly, the SADC FANR (2003) study showed that household wealth status is an important determinant of the vulnerability of HIV/AIDS-affected households to food insecurity. Nevertheless, HIV/AIDS often worsens household poverty, and more than one in five HIV-affected households in our study were among the poorest of the poor. This suggests compounded vulnerabilities among a large number of households hit by HIV/AIDS.

Policy and programme recommendations based on this finding would be to enhance food security by targeting vulnerable households broadly, rather than limiting the focus solely to households affected by HIV/AIDS. Indeed, the findings more generally suggest that interventions aimed at poverty reduction would have the greatest impact on food security, including for poor mortality-affected households, which represent one of a range of vulnerable categories.

Finally, we conclude with two comments on methodology. First, this study was cross-sectional in design, which has certain limitations. For example, this precludes examination of HIV/AIDS-related morbidity on household food security prior to the death of a household member. Also, since non-HIV mortality households generally had a higher SES, they may recover from the shock more quickly than HIV/AIDS-affected households, despite possibly being more severely affected by the death in the short term. Longitudinal studies are thus needed to gain greater understanding of the longer-term dynamics between adult mortality, livelihoods and food security at the household level.

Second, this study did not consider the impacts of HIV/AIDS on food security at the community level. The rising rate of mortality among prime-age adults has far-reaching impacts on human and social capital at this level (Whiteside, 2002). This is exacerbated by stigma, which has been shown to be both extensive and intensive in the study area (Niehaus, 2007). Evidence from another rural area of South Africa, KwaZulu-Natal, points to the positive role of social capital in food security (Misselhorn, 2009). This suggests that food security could be negatively affected in communities where this capital is eroded by the high incidence of HIV/AIDS. It may indeed be at the community level that HIV/AIDS emerges as a unique shock, and this requires further research. Even so, given the pandemic's continued reshaping of regional rural livelihood strategies, the suggestive findings presented here offer useful insights into the complex nexus between HIV/AIDS, household food security and poverty.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) (grant 2006×110.WIT), via the Regional Network on HIV/AIDS, Rural Livelihoods, and Food Security (RENEWAL), and was indirectly supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant 085477/Z/08/Z) through its support of the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System. This research has benefited form the NICHD-funded University of Colorado Population Center (grant R21 HD51146) through administrative and computing support. The authors are grateful to the University of the Witwatersrand/Medical Research Council's Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Wits/MRC Agincourt Unit) for their support with logistics, fieldworkers, data, administration and advice. Dr Paul Pronyk (RADAR) is acknowledged for comments on the design of the household questionnaire and sampling.

Footnotes

It should be noted that these ‘coping strategies’ are often at odds with the notion of successfully coping with crisis in the longer term (Davies, 1996; Maxwell et al., 1999).

We originally intended to interview 100 households in each stratum based on resources available for the project. However, insufficient households met the criteria for the ‘non-HIV mortality’ households. This enabled us to increase the sample size slightly for the other two strata.

References

- Aliber M. Chronic poverty in South Africa: Incidence, causes and policies. World Development. 2003;31:473–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett T, Blaikie PM. AIDS in Africa: Its Present and Future Impact. London: John Wiley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Baylies C. The impact of AIDS on rural households in Africa: A shock like any other? Development and Change. 2002;33:611–32. [Google Scholar]

- Clover J. Food security in sub-Saharan Africa. African Security Review. 2003;12:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Coates J, Webb P., Houser R. FANTA (Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project) Washington, DC: Academy for Education Development; 2003. Measuring Food Insecurity: Going beyond Indicators of Income and Anthropometry. [Google Scholar]

- Collinson MA, Tollman SM, Kahn K. Migration, settlement change and health in post-apartheid South Africa: Triangulating health and demographic surveillance with national census data. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007;35(69):77–84. doi: 10.1080/14034950701356401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies S. Adaptable Livelihoods: Coping with Food Insecurity in the Malian Sahel. London: Macmillan; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal A, Tumushabe J. HIV/AIDS and Food Security in Africa. London: UK Department for International Development; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- De Waal A, Whiteside A. New variant famine: AIDS and food crisis in southern Africa. The Lancet. 2003;362:1938–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14548-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FANTA (Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project) Measuring Household Food Insecurity Workshop Report, 15–16 April. Washington, DC: FANTA, Academy for Education Development; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie S, Kadiyala S. Food Policy Review No. 7. Washington, DC: IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute); 2005. HIV/AIDS and Food and Nutrition Security: From Evidence to Action. [Google Scholar]

- Gregson S, Mushati P, Nyamukapa C. Adult mortality and erosion of household viability in AIDS-afflicted towns, estates, and villages in eastern Zimbabwe. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2007;44:188–95. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000247230.68246.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad L, Gillespie S. Effective food and nutrition policy responses to HIV/AIDS: What we know and what we need to know. Journal of International Development. 2001;13:487–511. [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves JR, Pronyk PM. HIV/AIDS and rural development: Realities, relationships and responses. In: Greenburg S, editor. Development Update: Complexities, Lost Opportunities and Prospects – Rural Development in South Africa. 1. Vol. 4. Lexington: Interfund; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks S. The challenges facing empirical estimation of household food (in)security in South Africa. Development Southern Africa. 2005;22(1):103–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott J. Technical Guide No 7. Washington, DC: IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute); 1999. Choosing Outcome Indicators of Household Food Security. [Google Scholar]

- Hoddinott J, Yohannes Y. FANTA (Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project) Washington, DC: Academy for Education Development; 2002. Dietary Diversity as Household Food Security Indicator. [Google Scholar]

- Hosegood V, Vanneste A, Timaeus I. Levels and cause of adult mortality in rural South Africa: The impact of AIDS. AIDS. 2004;18:663–71. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200403050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter LM, Twine W, Patterson L. ‘Locusts are now our beef’: Adult mortality and household dietary use of local environmental resources in rural South Africa. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007;35(suppl. 69):165–74. doi: 10.1080/14034950701356385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. The impact of HIV/AIDS on food and nutrition security. Agriculture and Rural Development. 2002;2:8–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Tollman S, Garenne M, Gear J. Who dies of what? Determining cause of death in South Africa's rural north-east. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 1999;4:433–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1999.00415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Tollman SM, Garenne M, Gear JSS. Validation and application of verbal autopsies in a rural area of South Africa. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2000;5:824–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Garenne ML, Collinson MA, Tollman SM. Mortality trends in a new South Africa: Hard to make a fresh start. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007a;35(suppl. 69):26–34. doi: 10.1080/14034950701355668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn K, Tollman SM, Collinson MA, Clark SJ, Twine R, Clark BD, Shabangu M, Gomez-Olivé FX, Mokoena O, Garenne ML. Research into health, population and social transitions in rural South Africa: Data and methods of the Agincourt Health and Demographic Surveillance System. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2007b;35(suppl. 69):8–20. doi: 10.1080/14034950701505031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaschula SA. Wild foods and household food security responses to AIDS: Evidence from South Africa. Population and Environment. 2008;29:162–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S. Nutrition security, livelihoods and HIV/AIDS: Implications for research among farm worker households in South Africa. Public Health Nutrition. 2005;8:844–52. doi: 10.1079/phn2005739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loevinsohn M, Gillespie S. FCND (Food Consumption and Nutrition Division) Discussion Paper No. 157. Washington, DC: IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute); 2003. HIV/AIDS, Food Security, and Rural Livelihoods: Understanding and Responding. [Google Scholar]

- Marais H. Buckling: The Impact of HIV/AIDS in South Africa. Pretoria: Centre for the Study of AIDS. University of Pretoria; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Masanjala W. The poverty-HIV/AIDS nexus in Africa: A livelihood approach. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64:1032–41. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell DG. Measuring food insecurity: The frequency and severity of ‘coping strategies’. Food Policy. 1996;21:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell D, Ahiadeke C, Levin C, Armar-Klemesu M S, Lamptey GM. Zakariah Alternative food-security indicators: Revisiting the frequency and severity of ‘coping strategies’. Food Policy. 1999;24:411–29. [Google Scholar]

- Misselhorn A. Is a focus on social capital useful in considering food security interventions? Insights from KwaZulu-Natal. Development Southern Africa. 2009;26:189–208. [Google Scholar]

- Niehaus I. Death before dying: Understanding AIDS stigma in the South African lowveld. Journal of South African Studies. 2007;33:845–60. [Google Scholar]

- Peters PE, Kambewa D, Walker P. The Effects of Increased Rates of HIV/AIDS-Related Illness and Death on Rural Families in Zomba District, Malawi: A Longitudinal Study. Washington, DC: IFPRI (International Food Policy Research Institute)/Regional Network on AIDS, Livelihoods and Food Security; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Rose D, Charlton KE. Quantitative indicators from a food expenditure survey can be used to target the food insecure in South Africa. Journal of Nutrition. 2002;132:3235–42. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.11.3235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SADC FANR (South African Development Community: Food, Agriculture and Natural Resources Directorate) Towards Identifying Impacts of HIV/AIDS on Food Insecurity in Southern Africa and Implications for Response: Findings From Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. Harare: SADC FANR; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Jooste S, Pillay-Van-Wyk V, Mbelle N, Van Zyl J, Parker W, Zungu NP, Pezi S. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2008: A Turning Tide among Teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC (Human Sciences Research Council); 2009. [Google Scholar]

- StatsSA (Statistics South Africa) Measuring Poverty in South Africa. Pretoria: StatsSA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household Dietary Diversity Score (HDDS) for Measurement of Household Food Access: Indicator Guide. Washington, DC: FANTA (Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project), Academy for Education Development; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside A. Poverty and HIV/AIDS in Africa. Third World Quarterly. 2002;23:313–32. [Google Scholar]

- Yamano T, Jayne TS. Measuring the impacts of working-age adult mortality on small-scale farm households in Kenya. World Development. 2004;32:91–119. [Google Scholar]