Abstract

Purpose

Limited resection is an increasingly utilized option for treatment of clinical stage IA lung adenocarcinoma (ADC) ≤2 cm (T1aN0M0), yet there are no validated predictive factors for postoperative recurrence. We investigated the prognostic value of preoperative consolidation/tumor (C/T) ratio [on computed tomography (CT) scan] and maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) on 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography (PET) scan.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 962 consecutive patients who underwent limited resection for lung cancer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering between 2000 and 2008. Patients with available CT and PET scans were included in the analysis. C/T ratio of 25 % (in accordance with the Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201) and SUVmax of 2.2 (cohort median) were used as cutoffs. Cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR) was assessed.

Results

A total of 181 patients met the study inclusion criteria. Patients with a low C/T ratio (n = 15) had a significantly lower 5-year recurrence rate compared with patients with a high C/T ratio (n = 166) (5-year CIR, 0 vs. 33 %; p = 0.015), as did patients with low SUVmax (n = 86) compared with patients with high SUVmax (n = 95; 5-year CIR, 18 vs. 40 %; p = 0.002). Furthermore, within the high C/T ratio group, SUVmax further stratified risk of recurrence [5-year CIR, 22 % (low) vs. 40 % (high); p = 0.018].

Conclusions

With the expected increase in diagnoses of small lung ADC as a result of more widespread use of CT screening, C/T ratio and SUVmax are widely available markers that can be used to stratify the risk of recurrence among cT1aN0M0 patients after limited resection.

Keywords: Small lung adenocarcinoma, Limited resection, Positron emission tomography, SUVmax, Consolidation/tumor ratio

Lung cancer remains the most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States.1 Approximately 80 % of lung cancer patients are diagnosed with primary non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), of which the most common histologic subtype is adenocarcinoma (ADC).2,3 Recent improvements in imaging technologies and the widespread use of computed tomography (CT) screening have increased the probability of detecting small-sized, early-stage lung ADC (lung nodules that usually present in the periphery of the lung before onset of symptoms).4–6 Lobectomy with hilar and mediastinal lymph node dissection is currently the standard oncologic resection for operable NSCLC.7 Alternatively, with the aim of preserving pulmonary function, others have advocated for limited resection for low-grade malignancy lung cancers, especially ADCs, including ground-glass opacity (GGO).8 Areas of GGO on chest CT imaging often present as lepidic-predominant ADC, typified by lepidic growth along alveoli, without invasive areas.9–11 Previous studies have implied that the ratio of GGO component to solid component may be linked to the grade of the ADC malignancy.12–15 Furthermore, these studies have implied that the GGO/solid ratio is related to ADC aggressiveness and, consequently, to the risk of nodal involvement.12,16 However, a recent, large, phase II study demonstrated that preoperative radiographic findings on CT cannot accurately diagnose the pathologic invasiveness of small lung ADCs.17 Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) has become an integral part of NSCLC evaluation.18,19 Small-scale studies have demonstrated the role of FDG-PET/CT in assessing the biological status of cancers, but these investigations require confirmation in larger and more homogeneous cohorts.20–22 The ability to preoperatively distinguish biologically aggressive tumors from indolent tumors is highly desirable, and it may help surgeons to choose the most appropriate resection.

The purpose of this study was to assess the correlation between preoperative C/T ratio and SUVmax and postoperative recurrence in a cohort of early-stage lung ADC (≤2 cm) patients treated with limited resection.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

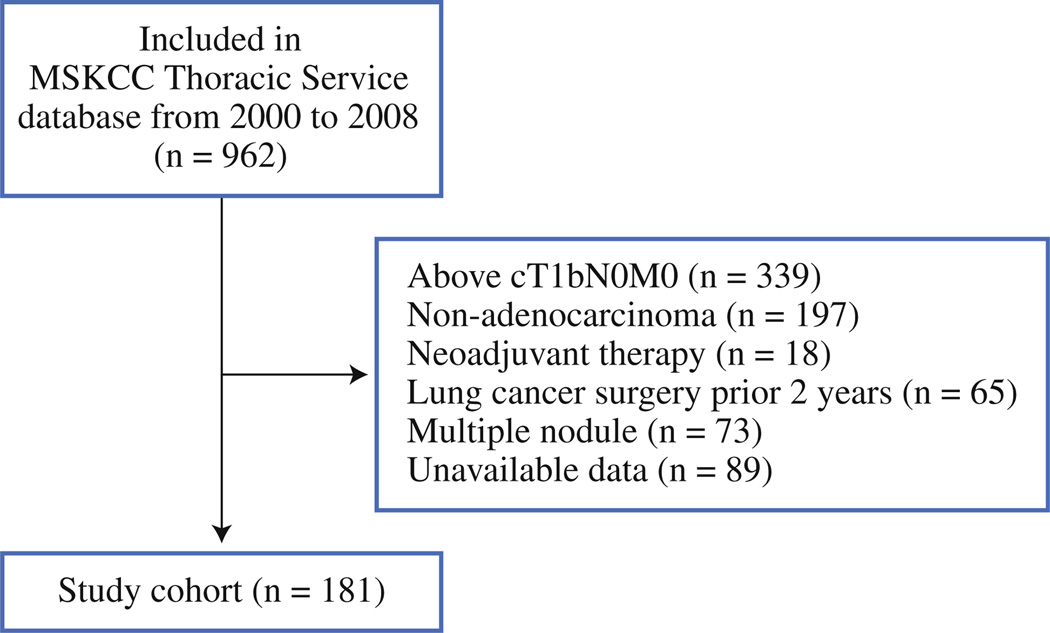

Following approval by the institutional review board at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC), we performed a retrospective review of 962 consecutive lung ADC patients who underwent limited resection for a lung nodule between January 2000 and December 2008. Medical records and a prospectively maintained database were reviewed to determine clinical variables. Exclusion criteria are listed in Fig. 1. Histologic diagnoses were based on the 2004 World Health Organization criteria for lung ADC.23 Pathologic stage (as defined in the 7th edition of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification24) was determined by review of pathology reports. Patient medical records were reviewed to determine the clinical rationale for limited resection. In this investigation, limited resection was defined as either wedge resection or anatomical segmentectomy.

FIG. 1.

Study cohort flow chart. In total, 962 patients with clinical T1aN0M0 lung adenocarcinoma who underwent limited resection were identified from 2000 to 2008. After exclusion, 181 patients were included in the analysis

Radiologic Evaluation of the Tumor

Tumor shadow images with size analysis were acquired by CT scan from the supraclavicular region through the adrenal glands. Axial CT scans for each patient were interpreted by two authors (J.N. and A.J.B.), who also measured tumor dimensions. Using the lung window setting, the radiologists confirmed the maximum tumor diameter and estimated the GGO and consolidation extent within the tumor.

Definition of Consolidation/Tumor (C/T) Ratio

To determine whether radiologic tumor density could serve as a predictor of tumor aggressiveness, we investigated C/T ratio. C/T ratio was defined as the proportion of the maximum consolidation (C) diameter divided by the maximum tumor (T) diameter. The maximum tumor diameter, the consolidation diameter, and the presence and extent of consolidation or GGO component in the tumor were determined digitally on the basis of the findings of CT scan of the lung window. The consolidation component was defined as an area of increased opacification that completely obscured underlying vascular markings. GGO was defined as an area of a slight, homogeneous increase in density that did not obscure underlying vascular markings. In statistical analyses using C/T ratio, a cutoff value of 25 % was used for correlation with postoperative recurrence and survival in our study cohort, on the basis of results obtained by the Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201 investigation.25

Technique of FDG-PET

All patients were evaluated by PET scan, and the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was recorded. PET scans were performed at multiple locations; 86 of the 181 included patients (48 %) underwent PET scan at MSKCC. For PET scans performed at MSKCC, patients received 10–15 mCi (370–555 MBq) of FDG intravenously, after fasting for a minimum of 6 h. Before injection, plasma glucose was measured and was <200 mg/dL in all patients. Approximately 60–90 min after injection, PET torso images were acquired using GE Advance (GE Medical Systems, Waukesha, WI) or EXACT HR plus (Siemens/CTI, Knoxville, TN) PET scanners. Beginning in November 2001, images also were acquired using a hybrid PET/CT imaging system (either Discovery LS [GE Medical Systems] or Biograph [Siemens/CTI]). The Discovery LS system incorporates Advance PET, and the Bio-graph incorporates HR plus PET. For PET/CT, a low-dose CT scan was acquired before PET scan, for attenuation correction of PET images and for anatomic localization of PET abnormalities. Each PET image was reconstructed using iterative algorithms, both with and without attenuation correction. All PET images were reviewed by experienced nuclear medicine physicians. FDG uptake was quantified by calculating SUVmax, using PET region-of-interest analysis, as follows:

We performed subgroup analysis of the cohort who had near-uniform data for time from FDG injection to image acquisition and for plasma glucose level before injection, with images obtained on MSKCC PET scanners. All FDG-PET studies were acquired on PET scanners, including Advance PET, Discovery STE, Discovery ST, Discovery LS (all GE Medical Systems), or Biograph.

Clinical Follow-up and Outcomes

The primary endpoint of our study was postoperative recurrence, as verified by biopsy. All patients were evaluated postoperatively with chest X-ray, chest CT scan, and PET scan, when clinically indicated, in addition to periodic clinical follow-up, in accordance with National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.26 Chest CT imaging was performed every 4–6 months for the initial 2 years postresection and then yearly after that. If patients were symptomatic, appropriate, standard-of-care testing was performed. Recurrences were classified in accordance with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Workforce recommendations.27

Statistics Analysis

Associations between clinicopathologic variables and histologic findings were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon test for continuous variables. Time-to-event endpoints were analyzed using competing risks analysis. Without competing risks analysis, simply censoring patients at the time of death would lead to a biased probability of recurrence (as estimated by the standard Kaplan– Meier method). Instead, the risk of recurrence [defined as the cumulative incidence of recurrence (CIR)] was estimated using a cumulative incidence function, which accounted for death without recurrence as a competing event. Patients were censored if they were alive and without a documented recurrence at the time of the most recent follow-up. Differences in CIR between groups were assessed using the methods of Gray.28 All tests for statistical significance were two-tailed and used a 5 % level of significance. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (version 2.14.1; R Development Core Team, 2011), including the “survival” and “cmprsk” packages.

RESULTS

Clinical Data

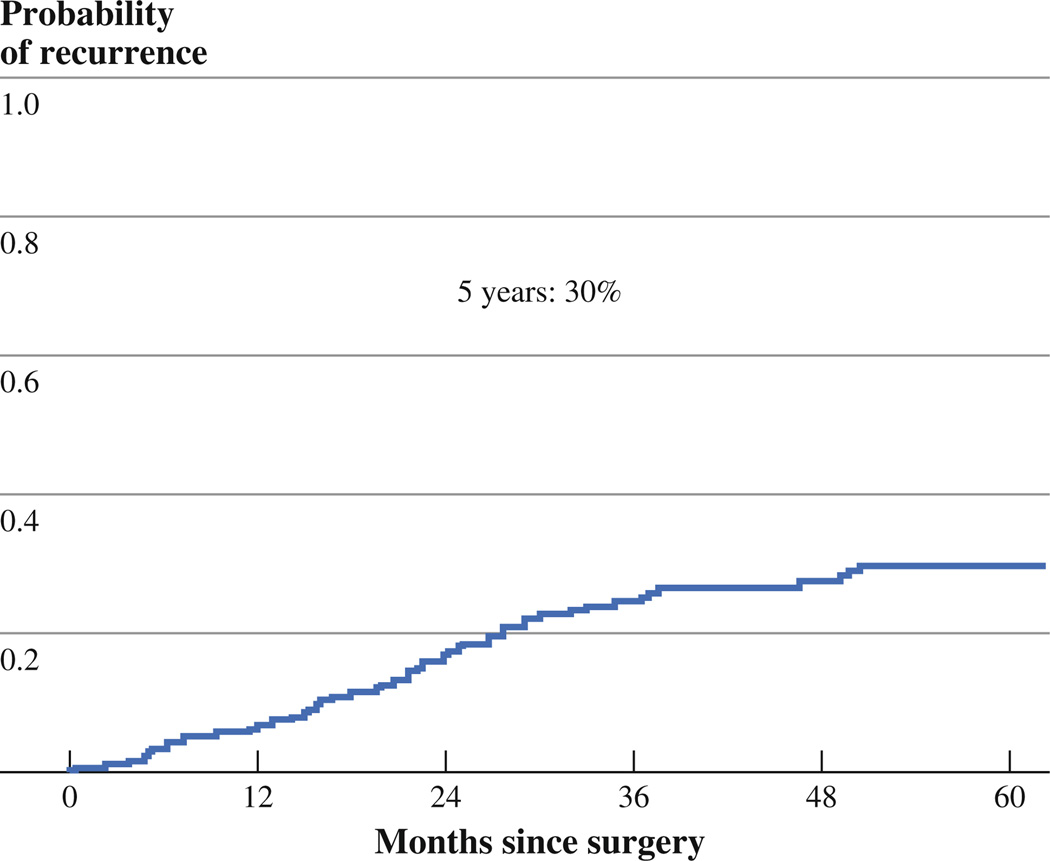

Clinicopathologic variables are listed in Table 1. A total of 181 patients were included in the study (Fig. 1): 155 (86 %) stage IA, 19 (10 %) stage IB, 6 (3 %) stage II (by reason of N1 station), and 1 (1 %) stage III (by reason of N2 station). Seven patients (3.9 %) with T1a tumors had lymph node metastasis. There were no statistically significant differences observed in patient characteristics, such as age, sex, smoking status, tumor location, and pathologic stage; there were, however, statistically significant differences detected in surgical procedure performed, tumor size by CT, and pathologic tumor size. The median follow-up was 37 months (range 0.3–134 months); the 5-year CIR was 30 % (Fig. 2).

TABLE 1.

Correlation between clinical characteristics and CT scan findings and SUVmax

| Characteristic | Total, N (%) | C/T <25 % N (%) |

C/T ≥25 % N (%) |

p Value | SUVmax <2.2 N (%) |

SUVmax ≥2.2 N (%) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 181 | 15 (8) | 166 (92) | 86 (48) | 95 (52) | ||

| Age, yr, median (range) | 70 (29–89) | 0.369 | 0.277 | ||||

| <65 | 54 (30) | 6 (11) | 48 (89) | 29 (54) | 25 (46) | ||

| ≥65 | 127 (70) | 9 (7) | 118 (93) | 57 (45) | 70 (55) | ||

| Sex | 0.241 | 0.757 | |||||

| Female | 120 (66) | 12 (10) | 108 (90) | 58 (48) | 62 (52) | ||

| Male | 61 (34) | 3 (5) | 58 (95) | 28 (46) | 33 (54) | ||

| Smoking history | 0.941 | 0.957 | |||||

| Never | 22 (12) | 2 (9) | 20 (91) | 10 (45) | 12 (55) | ||

| Former | 139 (77) | 11 (8) | 128 (92) | 66 (47) | 73 (53) | ||

| Current | 20 (11) | 2 (10) | 18 (90) | 10 (50) | 10 (50) | ||

| Tumor location | 0.418 | 0.291 | |||||

| RUL | 44 (24) | 5 (11) | 39 (89) | 24 (55) | 20 (45) | ||

| RML | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (100) | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | ||

| RLL | 42 (23) | 1 (2) | 41 (98) | 24 (57) | 18 (43) | ||

| LUL | 52 (29) | 4 (8) | 48 (92) | 21 (40) | 31 (60) | ||

| LLL | 39 (22) | 5 (13) | 34 (87) | 16 (41) | 23 (59) | ||

| Surgical procedure | 0.317 | 0.010a | |||||

| Wedge resection | 124 (69) | 12 (10) | 112 (90) | 67 (54) | 57 (46) | ||

| Segmentectomy | 57 (31) | 3 (5) | 54 (95) | 19 (33) | 38 (67) | ||

| CT tumor size, mm, mean (range) | 1.4 (0.4–2.0) | 0.573 | 0.011a | ||||

| 0–10 | 38 (21) | 4 (11) | 34 (89) | 25 (66) | 13 (34) | ||

| 11–20 | 143 (79) | 11 (8) | 132 (92) | 61 (43) | 82 (57) | ||

| Pathologic tumor size, mm, mean (range) | 1.2 (0.4–5.0) | 0.002a | 0.0001a | ||||

| 1–10 | 53 (29) | 10 (19) | 43 (81) | 37 (70) | 16 (30) | ||

| 11–20 | 111 (61) | 3 (3) | 108 (97) | 40 (36) | 71 (64) | ||

| 21–50 | 17 (10) | 2 (12) | 15 (88) | 9 (53) | 8 (47) | ||

| SUVmax, median (range) | 2.2 (0.6–16) | 0.0001a | |||||

| <2.2 | 86 (48) | 15 (17) | 71 (83) | ||||

| ≥2.2 | 95 (52) | 0 (0) | 95 (100) | ||||

| Pathologic stage | 0.433 | 0.121 | |||||

| IA | 155 (86) | 15 (10) | 140 (90) | 78 (50) | 77 (50) | ||

| IB | 19 (10) | 0 (0) | 19 (100) | 6 (32) | 13 (68) | ||

| II | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 1 (17) | 5 (83) | ||

| III | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) |

CT computed tomography, C/T consolidation/tumor, LLL left lower lobe, LUL left upper lobe, RLL right lower lobe, RML right middle lobe, RUL right upper lobe, SUVmax maximum standardized uptake value

Statistically significant (p < 0.05)

FIG. 2.

5-year recurrence-free probability in the study cohort

Association Between C/T Ratio and Recurrence

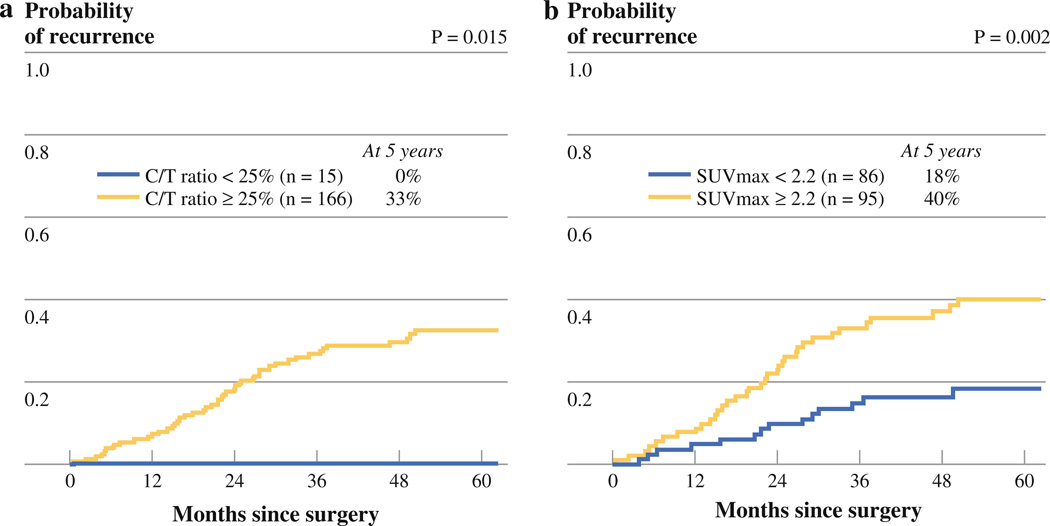

The patients were classified into two groups by C/T ratio, as previously reported: low C/T ratio (<25 %) and high C/T ratio (≥25 %).25 Of the 181 patients eligible for analysis, 15 patients had a low C/T ratio, and 166 patients had a high C/T ratio. As shown in Fig. 3a, patients with a low C/T ratio had a significantly lower CIR compared with patients with a high C/T ratio (5-year CIR, 0 vs. 33 %; p = 0.015).

FIG. 3.

a 5-year recurrence-free probability stratified by consolidation/tumor (C/T) ratio. b 5-year recurrence-free probability stratified by maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax)

Association Between SUVmax and Recurrence

SUVmax ranged from 0.6 to 16 (median, 2.2; mean ± SD, 2.5 ± 2.4). We categorized tumors into two cohorts based on the median SUVmax (2.2): low (<2.2; n = 86) and high (≥2.2; n = 95). High SUVmax was associated with increased risk of recurrence compared with low SUVmax (5-year CIR, 40 vs 18 %; p = 0.002; Fig. 3b).

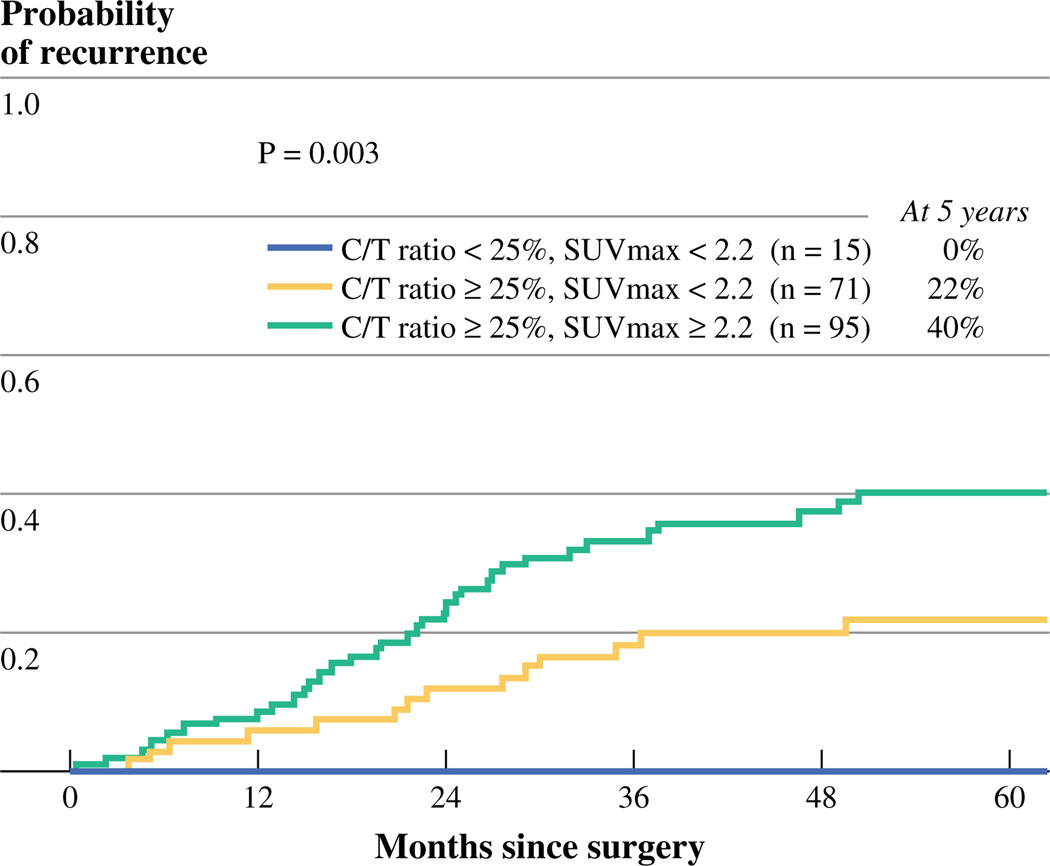

Association Between Combined C/T Ratio and SUVmax Groups and Recurrence

We next assessed the ability to further stratify patients in each C/T ratio group by SUVmax. In the low C/T group, all patients (n = 15) had SUVmax <2.2, and no recurrences were observed. In the high C/T group, SUVmax stratified two groups, with different prognosis: high SUVmax (n = 95) was associated with significantly increased risk of recurrence, compared with low SUVmax (n = 71) (5-year CIR, 40 vs. 22 %; p = 0.018). Overall, the risk of recurrence was significantly different (p = 0.003) between the three patient groups (low C/T and low SUVmax group, high C/T and low SUVmax group, high C/T and high SUVmax group) (Fig. 4). Subgroup analysis of cohorts of patients who underwent PET or PET/CT scan at MSKCC or at outside centers did not reveal any significant differences (Supplemental Table 1).

FIG. 4.

5-year recurrence-free probability stratified by combining consolidation/tumor (C/T) ratio and maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax)

DISCUSSION

Limited resection was once reserved for high-risk lung cancer patients who lacked the pulmonary reserve for formal lobectomy or who possessed multiple primary lung cancers requiring resection. Recently, the indication for limited resection has been extended to include early-stage lung cancers that are located peripherally and that demonstrate GGO predominance.29,30 With the increasing use of limited resection for early-stage lung ADC, it is important to identify the subgroup of patients who may be at increased risk for postoperative recurrence as a result of undergoing a nonanatomic resection. Herein, we have attempted to determine noninvasive modalities (C/T ratio and SUVmax) that can be used to inform and stratify a patient’s risk of recurrence.

In this study, the 5-year CIR for patients who underwent wedge resection was higher than that for patients who underwent segmentectomy, but the difference was not significant (p = 0.33). We observed increased postoperative recurrence rates with C/T ratio ≥25 % and SUVmax ≥2.2. In our study cohort, patients with a C/T ratio ≥25 % experienced recurrence more frequently; this group was further stratified by SUVmax, identifying two discrete groups with markedly different recurrence-free survival. All patients with a C/T ratio <25 % survived without recurrence during the first 5 years, despite undergoing limited resection. In patients with a C/T ratio <25 % and in patients with SUVmax <2.2, limited resection was an adequate treatment, with disease-free survival rates nearly as high as those in similar groups of patients treated with lobectomy. This finding implies that these cutoffs may indicate a “radiologic noninvasive tumor.” Because most recurrences following limited resection are locoregional rather than distant, we performed a subgroup analysis and confirmed that C/T ratio ≥25 % and SUVmax ≥2.2 remained prognostic.

In addition to the limitations of retrospective studies, our investigation was potentially confounded by the fact that the PET scans included in our study were performed at multiple locations. Subgroup analysis found no significant differences between the MSKCC cohort and the cohort of patients who underwent scans at outside institutions.

CONCLUSIONS

This study demonstrates that C/T ratio (on CT scan) and SUVmax (on PET scan) may reflect the aggressiveness of cT1aN0M0 lung ADC. Our observations will be of use in designing future prospective clinical trials for T1aN0M0 lung ADC patients.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Joe Dycoco for his help with the lung adenocarcinoma database at the Division of Thoracic Service, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and David Sewell, for his editorial assistance.

FUNDING This work was supported, in part, by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Young Investigator Award; National Lung Cancer Partnership/LUNGevity Foundation Research Grant; American Association for Thoracic Surgery Third Edward D. Churchill Research Scholarship; William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin, the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research and the Experimental Therapeutics Center; the National Cancer Institute (Grants U54CA137788 and U54CA132378); and the U.S. Department of Defense (Grant LC110202).

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3212-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Disclosure The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devesa SS, Bray F, Vizcaino AP, et al. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: male:female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:294–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents. IX. Lyon: IARC; 2007. IARC Scientific Publications No. 160. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Libby DM, et al. Survival of patients with stage I lung cancer detected on CT screening. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1763–1771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hocking WG, Hu P, Oken MM, et al. Lung cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:722–731. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aberle DR, Berg CD, Black WC, et al. The National Lung Screening Trial: overview and study design. Radiology. 2011;258:243–253. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginsberg RJ, Rubinstein LV. Randomized trial of lobectomy versus limited resection for T1 N0 non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Study Group. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:615–622. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00537-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okada M, Koike T, Higashiyama M, et al. Radical sublobar resection for small-sized non-small cell lung cancer: a multicenter study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:769–775. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuriyama K, Seto M, Kasugai T, et al. Ground-glass opacity on thin-section CT: value in differentiating subtypes of adenocarcinoma of the lung. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:465–469. doi: 10.2214/ajr.173.2.10430155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jang HJ, Lee KS, Kwon OJ, et al. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: focal area of ground-glass attenuation at thin-section CT as an early sign. Radiology. 1996;199:485–488. doi: 10.1148/radiology.199.2.8668800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakata M, Saeki H, Takata I, et al. Focal ground-glass opacity detected by low-dose helical CT. Chest. 2002;121:1464–1467. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, et al. Correlation between computed tomographic findings, bronchioloalveolar carcinoma component, and biologic behavior of small-sized lung adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:857–861. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakayama H, Yamada K, Saito H, et al. Sublobar resection for patients with peripheral small adenocarcinomas of the lung: surgical outcome is associated with features on computed tomographic imaging. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;84:1675–1679. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dong B, Sato M, Sakurada A, et al. Computed tomographic images reflect the biologic behavior of small lung adenocarcinoma: they correlate with cell proliferation, microvascularization, cell adhesion, degradation of extracellular matrix, and K-ras mutation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:733–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu K, Yamada K, Saito H, et al. Surgically curable peripheral lung carcinoma: correlation of thin-section CT findings with histologic prognostic factors and survival. Chest. 2005;127:871–878. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.3.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, et al. Discrepancy of computed tomographic image between lung and mediastinal windows as a prognostic implication in small lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1828–1832. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01077-4. Discussion 1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki K, Koike T, Asakawa T, et al. A prospective radiological study of thin-section computed tomography to predict pathological noninvasiveness in peripheral clinical IA lung cancer (Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201) J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:751–756. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821038ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pieterman RM, van Putten JW, Meuzelaar JJ, et al. Preoperative staging of non-small-cell lung cancer with positron-emission tomography. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:254–261. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vansteenkiste J, Fischer BM, Dooms C, et al. Positron-emission tomography in prognostic and therapeutic assessment of lung cancer: systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:531–540. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(04)01564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada M, Tauchi S, Iwanaga K, et al. Associations among bronchioloalveolar carcinoma components, positron emission tomographic and computed tomographic findings, and malignant behavior in small lung adenocarcinomas. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:1448–1454. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama H, Okumura S, Daisaki H, et al. Value of integrated positron emission tomography revised using a phantom study to evaluate malignancy grade of lung adenocarcinoma: a multicenter study. Cancer. 2010;116:3170–3177. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nomori H, Watanabe K, Ohtsuka T, et al. Fluorine 18-tagged fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic scanning to predict lymph node metastasis, invasiveness, or both, in clinical T1 N0 M0 lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:396–401. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. World Health Organization classification of tumors: pathology and genetics of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. Lyon: IARC Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, et al. The IASLC Lung Cancer Staging Project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM Classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K, Koike T, Asakawa T, et al. A prospective radiological study of thin-section computed tomography to predict pathological noninvasiveness in peripheral clinical IA lung cancer (Japan Clinical Oncology Group 0201) J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:751–756. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31821038ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ettinger DS, Akerley W, Bepler G, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:740–801. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donington J, Ferguson M, Mazzone P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians and Society of Thoracic Surgeons consensus statement for evaluation and management for high-risk patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2012;142:1620–1635. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-0790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gray RJ. A class of K-sample tests for comparing the cumulative incidence of a competing risk. Ann Stat. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Okada M, Nishio W, Sakamoto T, et al. Effect of tumor size on prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: the role of segmentectomy as a type of lesser resection. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keenan RJ, Landreneau RJ, Maley RH, Jr, et al. Segmental resection spares pulmonary function in patients with stage I lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:228–233. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.