Abstract

Skeletal muscle interstitium is crucial for regulation of blood flow, passage of substances from capillaries to myocytes and muscle regeneration. We show here, probably, for the first time, the presence of telocytes (TCs), a peculiar type of interstitial (stromal) cells, in rat, mouse and human skeletal muscle. TC features include (as already described in other tissues) a small cell body and very long and thin cell prolongations—telopodes (Tps) with moniliform appearance, dichotomous branching and 3D-network distribution. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed close vicinity of Tps with nerve endings, capillaries, satellite cells and myocytes, suggesting a TC role in intercellular signalling (via shed vesicles or exosomes). In situ immunolabelling showed that skeletal muscle TCs express c-kit, caveolin-1 and secrete VEGF. The same phenotypic profile was demonstrated in cell cultures. These markers and TEM data differentiate TCs from both satellite cells (e.g. TCs are Pax7 negative) and fibroblasts (which are c-kit negative). We also described non-satellite (resident) progenitor cell niche. In culture, TCs (but not satellite cells) emerge from muscle explants and form networks suggesting a key role in muscle regeneration and repair, at least after trauma.

Keywords: telocytes, telopodes, interstitial cells, striated/skeletal muscle, satellite cells, muscle regeneration/repair, shed vesicles, non-satellite progenitor cell niche, intercellular signalling, c-kit, caveolin-1, VEGF

Introduction

Significant plasticity depending on loading and regenerative capability after mechanical injury are extensively studied features of skeletal muscle. Skeletal muscle interstitium (stroma) seems to play a crucial role in the regulation of these processes [1–4]. A subset of cells, named ‘satellite cells’, located between the basal lamina and sarcolemma is believed to be the precursor of skeletal muscle fibres, which are able to proliferate, differentiate and migrate after muscular injury [5–19]. However, the challenge of using muscle progenitor cells for skeletal muscle reconstruction in animal models or humans has not been solved to date, mainly because of scarce graft cell survival, explained by lack of adequate paracrine factors, tissue guidance and blood vessel scaffold [20–29].

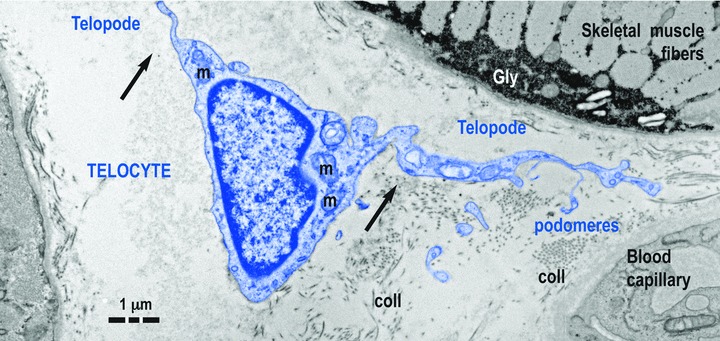

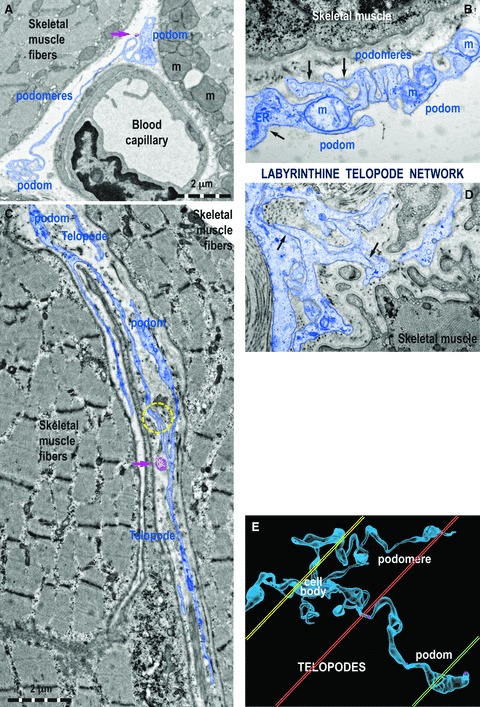

We previously demonstrated in a variety of cavitary and non-cavitary organs [30, 32] a peculiar type of interstitial cells that we named telocytes (TCs), replacing the former name Interstitial Cajal-Like Cells (ICLCs). Although both types of cells, TCs and ICLCs, initially seemed similar, in fact they are completely different, not only semantically. We have shown, by electron microscopy, the existence of TCs in epi-, myo- and endocardium, where TCs appeared in tandem with resident or migrated stem cells, forming together the so-called cardiac stem-cell niches [31, 33–40]. TCs have a small cell body and specific (unique) prolongations that we named telopodes (Tps). Tps are characterized by (a) number (1–5/cell, frequently 2 or 3); (b) length (tens up to hundreds of micrometeres); (c) moniliform aspect—an alternation of thin segments, podomeres (with calibre under 200 nm, below the resolving power of light microscopy) and dilated segments, podoms, which accommodate mitochondria, (rough) endoplasmic-reticulum and caveolae and (d) dichotomous branching pattern forming a 3D labyrinthine network. Significantly, TCs (especially Tps) release shed vesicles and exosomes, sending macromolecular signals to neighbour cells, thus modifying their transcriptional activity, eventually. TCs concept was quickly adopted by other laboratories [41–56]. Noteworthy, the microRNA expression (e.g. miR-193) clearly differentiate TCs from other stromal cells, at least in myocardium [57].

Here we present, unequivocally, visual evidence for the presence of TCs within the skeletal muscle interstitial spaces of mammals (humans and rodents). We suggest that TCs might be key players in skeletal muscle regeneration/repair.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Rat skeletal muscle samples were obtained from three 6-month-old Wistar rat quadriceps femoral muscle. Mouse skeletal muscle samples were obtained from 4-month-old C57 black mice. Human skeletal muscle samples were obtained from two patients undergoing quadriceps muscle biopsy for diagnosis, and muscle pathology was ruled out. This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the “Victor Babeş” National Institute of Pathology, Bucharest, according to generally accepted international standards.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

TEM was performed on small (1 mm3) tissue fragments, processed according to routine Epon-embedding procedure, as we previously described [33, 35]. About 60-nm-thin sections were examined with a Morgagni 286 transmission microscope (FEI Company, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at 60 kV. Digital electron micrographs were recorded with a MegaView III CCD using iTEM-SIS software (Olympus, Soft Imaging System GmbH, Münster, Germany). TCs and Tps were digitally coloured in blue on TEM images using Adobe© Photoshop CS3 to highlight them.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

The histological stains and immunohistochemistry were performed on cryosections. The skeletal muscle specimen was frozen in isopentan in liquid nitrogen and cut at a thickness of 7 mm using a Thermo Scientific cryostat. A routine histological vital staining was performed with methylene blue 1% for 1.5–2 min. Immunohistochemical studies were performed on tissue pre-incubated with BSA 3% in PBS, 1 hr at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were: anti-c-Kit polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:100; Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-vimentin monoclonal mouse antibody (1:50; DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), anti-caveolin-1 mouse monoclonal antibody (1:250; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and anti-VEGF (1:75; Santa-Cruz). After 1-hr incubation, at room temperature, immunoreactivity was detected with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, after peroxidase blocking. The chromogen/substrate used was DAB. Control tissues were prepared in the same way, omitting the primary antibody. Striated muscle sections were examined with a Nikon Eclipse TE 300 microscope.

Cell cultures

Adult C57 black mice were first treated with 1000 U/kg heparin and subsequently sacrificed by cervical dislocation.

Mouse thigh was dissected under the stereomicroscope and the entire medial package was transferred in transport medium and processed for cell cultures.

To obtain cell cultures highly enriched in interstitial cells from mice skeletal muscle, the samples were mechanically minced into small pieces of about 1 mm3. We used fragments of explants (cross-cut fragments of skeletal muscle) to see what type of cells emerge in the medium. Tissue fragments were first incubated in 0.05% trypsin/0.02% EDTA (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany) at 37°C for 5 min. and then placed in 35 cm2 Petri dishes and left to adhere. After 5 min., the explants were covered with DMEM/F12 culture medium supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum and 100 U/ml penicillin—100 mg/ml streptomycin (all from Sigma-Aldrich).

After 10 days, the migrated cells were detached from the culture vessel and replated on glass cover slips for immunolabelling.

Immunofluorescence of cultured cells

Cells grown on cover slips were fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 10 min., washed in PBS, then incubated in PBS containing 2% bovine serum albumin for another 10 min. Afterwards, the cells were permeabilized with 0.075% saponin for 10 min. (all reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich). Incubation with the primary antibodies was performed over night, at 4°C, using rabbit anti-c-kit and goat anti-vimentin (both from Santa-Cruz, 1:100). After three serial rinses, the primary antibodies were detected with secondary anti-rabbit or anti-goat antibodies conjugated to AlexaFluor 488, both from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Finally, the nuclei were counterstained with 1 mg/ml DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich).

Samples were examined under a Nikon TE300 microscope equipped with a Nikon DX1 camera, Nikon PlanApo 100× objectives, and the appropriate fluorescence filters.

Vital staining of cultured cells

Cells grown on cover slips were labelled with MitoTracker Green FM (Molecular Probes), vital chemical marker for mitochondria. Cells were incubated with 100 nM MitoTracker Green FM in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum and 100 U/ml penicillin—100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were washed and examined by fluorescence microscopy (450–490 nm excitation light, 520 nm barrier filter; Nikon TE300 microscope).

Results

Electron microscopy

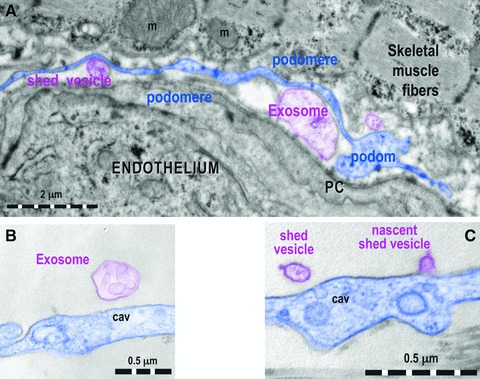

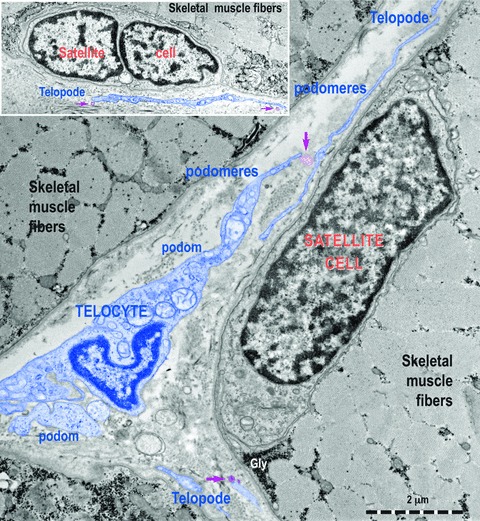

Electron microscopy showed that TCs (Figs 1–7) were present in skeletal muscle interstitium in both human (Figs 1–7) and rat (Figs 2–3) specimens. TCs formed a labyrinthine system as a result of overlapping Tps (Fig. 3C and D) and were organized in a network alongside the striated muscle cells and vascular system (Figs 1, 2 and 3A). The shape of TCs was either triangular (Fig. 1) or spindle (Fig. 2A and C), depending on the number of visible Tps (embedded in the 60-nm-thick section; Fig. 3E). The Tps had a narrow emergence from the cellular body (Figs 1 and 2B) and were extremely long (45–90 μm) and sinuous (Figs 2C and 3B). The moniliform aspect of Tps was because of the uneven calibre (Figs 1–3) and the irregular alternation of podomeres, thin (40–100 nm) segments, with podoms, dilatations (150–500 nm) containing mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and caveolae (Figs 1, 3, 5 and 6). This typical aspect enable the recognition of segments of Tps, which appeared separated from TCs cellular body as a result of specimen sectioning (Figs 2A, 3C and E and 6). TCs often extended their Tps between small folds in the periphery of muscle-striated cells (Fig. 3C and D). Shed vesicles and exosomes were found in the vicinity of Tps (Figs 2, 3 and 5). Tps were interconnected by different types of junctions: manubria adhaerentia (Fig. 4A), puncta adhaerentia (Fig. 4B) and small electron dense structures (Fig. 4). Electron microscopy of striated muscle showed as well that TCs are often located in the close vicinity of satellite cells (Fig. 6), striated cells with regenerative features (Fig. 6, inset) or even putative progenitor cells (Figs 7 and 8). Notably, such cells were located in between adult skeletal muscle cells in contrast to satellite cells, which are enclosed by muscle fibres basal lamina (Fig. 6).

Fig 1.

Telocyte (TC) in human skeletal muscle interstitium: two striated fibres and a blood capillary (transmission electron microscopy). Cellular body of TC (digitally coloured in blue) has a thin layer of cytoplasm with few mitochondria (m) around nucleus. Telopodes (Tps) have a narrow emergence (arrows) from cellular body. Tps have a sinuous trajectory, podomeres (extremely thin segments, below the resolving power of light microscopy) and podoms (dilated portions). coll: collagen fibres.

Fig 2.

Human TC (A, B) and rat TC (C) in skeletal muscle interstitum. Shed vesicles (purple, arrows) can be seen in the vicinity of telopodes. Tps are characteristic thin cellular prolongations that increase telocytes length (A: 45 μm, B: –61 μm). Tps show podomeres (about 40 nm thickness) alternating with podoms (dilations of about 400 nm wide). N: nucleus.

Fig 3.

Ultrastructural features of Tps in rat (A) and human (B–D) striated muscle. (A) One Tp in between a blood capillary and two striated muscle fibres (m, mitochondria). (B) Details of a podom, which accommodates mitochondria (m), endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and caveolae (black arrows). (C, D) Tps with bifurcations and a labyrinthine configuration among striated muscle cells. The yellow circle (C) and black arrows (D) indicate close contacts between Tps of different TC. (E) Computer simulation of a 3D representation of a TC outside the tissular environment. Note that various sections (coloured in yellow, orange and green) contain different segments of Tps.

Fig 5.

(A) One Tp (digitally blue coloured) positioned in between a capillary endothelium and striated muscle cell releases shed vesicles and exosomes (digitally purple coloured). PC: pericyte. Higher magnifications of podoms that show an exosome (B) and a nascent shed vesicle (C), in both cases digitally purple coloured. cav: caveolae.

Fig 4.

Tps are connected by different types of junctions: manubria adhaerentia (A, arrows) or puncta adhaerentia minima (B, encircled). Note the extreme calibre of at least some portions of podomeres: comparable with collagen fibres (A) and, also, with cross-cut thick and thin myo-filaments (B). coll: collagen fibres; m: mitochondria.

Fig 6.

Transmission electron micrographs show TC with Tps, podoms and podomeres in between muscle fibres. Note the typical appearance of satellite cells. TC (digitally blue coloured) are positioned in the close vicinity of satellite cells. Two ultrastructural features are remarkable: the close spatial relationships of Tps with satellite cells and the fact that these Tps release shed vesicles (purple arrows). This may indicate that a transfer of chemical information flow from TC to satellite cells.

Fig 7.

Electron micrographs of human skeletal muscle show a TC (blue coloured), which extends its Tps indicated by red arrows around a striated cell, in fact a (putative) progenitor cell. Note: the tandem TC—progenitor cell making a non-satellite (resident) progenitor stem cell niche. Inset: Higher magnification of the progenitor cell shows incompletely differentiated features: unorganized myofilaments (mf), glycogen deposits (Gly), prominent Golgi complex (G). N: nucleus; nc: nucleolus.

Fig 8.

A higher magnification of a field that suggests a non-satellite (resident) progenitor cell. No satellite cells are seen. The sarcomeres are formed. Z: Z lines; mf: myofilaments (thick and thin).

Immunohistochemistry

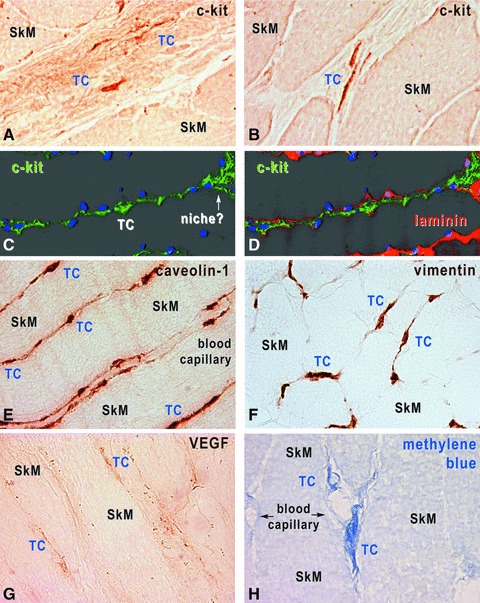

In skeletal muscle interstitium, TCs became apparent with a short exposure of cryosections to methylene blue staining (Fig. 9), as we reported for other tissues. Immunostaining for proteins typically expressed by TCs (c-kit, caveolin-1, vimentin and VEGF) revealed individual interstitial cells, with long and thin cell processes in a network distribution (Tps), both in human (Fig. 9) and rat (data not shown) muscle specimens. The location of cells with TC phenotype was restricted to perimysium and endomysium, their cell prolongations being in contact with blood vessels and nerve endings (Fig. 9), as seen in more detail with TEM. No obvious differences of immunostaining pattern or TC distribution were found in human and rat skeletal muscles examined.

Fig 9.

Human skeletal muscle, immunohistochemistry with HRP conjugated antibodies on cryosections (A, B, E, H) and immunofluorescence-confocal microscopy (C, D). TCs are located within interstitium, and express c-kit (A–D), caveolin-1 (E), vimentin (F) and VEGF (G). TCs were also revealed by methylene blue vital staining (H). In C and D, TCs are identified by c-kit expression (green), the basal lamina by laminin expression (red) and nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Original magnification 1000×.

Cell explants

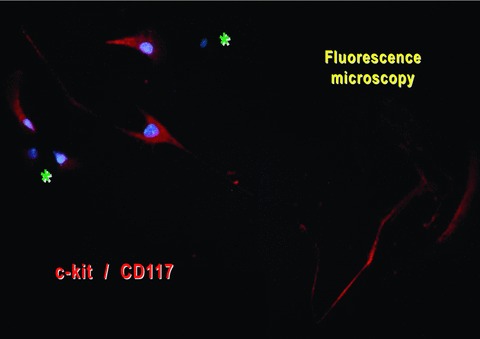

When a small piece of muscle was placed in a Petri dish, after 3 days, spindle-shaped cells emerged from the explant and started to build an extensive cellular network around the original tissue fragment (Fig. 10). Most of the migrated explant cells corresponded to TC morphological profile, with long, thin and moniliform Tps (Fig. 10). Indeed, these cells appeared c-kit positive (Fig. 11).

Fig 10.

Phase contrast microscopy of mouse skeletal muscle explant culture (day 7). (A) TCs emerge from a muscle tissue fragment and (B) form a cellular network starting from explant. (A, B) original magnification: 40×. (C) TCs with typical morphology, small cell body and telopodes with characteristic ‘beads-on-a-string’ conformation. (D) TCs appear interconnected by their telopodes. (C, D) original magnification: 200×.

Fig 11.

Mouse-striated muscle primary cell culture (day 8). Immunofluorescent labelling for c-kit shows the presence of positive cells (red) with a typical aspect of TC (very long and thin moniliform prolongations). Nuclei were counterstained blue with DAPI. There are also c-kit/CD117-negative cells (asterisks).

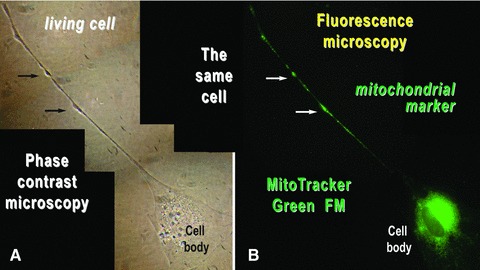

The dilations along Tps, called podoms, accommodate many mitochondria as shown by fluorescent labelling of living cells with the lipophylic, selective dye MitoTracker Green FM, which is concentrated by active mitochondria (Fig. 12).

Fig 12.

Mouse skeletal muscle in cell culture. The same cell was analysed by (A) phase contrast microscopy and (B) fluorescence microscopy after labelling the mitochondria of living cells with MitoTracker Green FM. Mitochondria are concentrated around the cell nucleus and within the podoms (arrows). Photographic reconstruction; original magnification: 1000×.

Such cells strongly expressed c-kit both on cell body and Tps (Fig. 11) and had mitochondria concentrated around the cell nucleus and within the podoms (Fig. 12). These cultured cells were all Pax-7 negative (data not shown).

Discussion

The components of skeletal muscle interstitium take part in regulation of blood flow and metabolism, myocyte plasticity and regeneration [60]. Considering that both tissue formation and myocyte adaptation are guided by refined cell contacts and molecular interactions [61], a continuous interplay between connective tissue and skeletal muscle seems to take place from embryonic development, through adult life, to ageing. Here we produced evidence that TCs are located in the interstitium of mouse, rat and human skeletal muscle. TCs might regulate a variety of physiological processes in muscle tissue.

TC characteristics and identification

We previously described TCs in a variety of cavitary (heart, stomach and intestine, gallbladder, uterus and Fallopian tube) and non-cavitary organs (lungs and pleura, exocrine pancreas, mammary gland and placenta) [38]. TCs are characterized by a small (∼10 μm) cell body, with scarce cytoplasm, and by typical thin and long (up to hundreds of μm) cell prolongations (Tps), with moniliform aspect, branching and organization in a labyrinthine system, features that can be observed with TEM. TCs constantly express different protein markers, such as c-kit, caveolin-1, CD34, vimentin and VEGF [30], which make them identifiable by immunohistochemistry.

Fibroblasts differ from TCs because of their short (range of micrometers) cell processes with thick emergence from the cell body and to a different phenotype (c-kit negative) [30]. Although fibroblasts have as main function the generation of collagen, a basic component of the connective tissue matrix, TCs link up different cell types by their long cell processes, being able to carry signals over long distances. Satellite cells cannot be mistaken as TCs because they are located between the sarcolemma and the surrounding basal lamina of the muscle fibres and have no cell prolongations [14, 62]. TCs are placed in the endomysium and perimysium and send their Tps over long distances. However, TCs in cultures were c-kit positive and Pax-7 negative, finding which clearly distinguishes them from both fibroblasts and stem cells.

TC network and contacts

By TEM, we were able to identify in the interstitium, among striated muscle fibres, typical very long and thin Tps, with moniliform appearance, in close vicinity of capillaries, nerve endings, satellite cells or even cells with regenerative aspects. We also showed that Tps are able to form cellular junctions, which suggest that TCs are organized in a 3D interstitial network. TCs followed the same arrangement pattern in cell cultures, where they formed in vitro networks after a remarkable migration from tissue explants. This peculiar migrating capacity, which differentiates TCs from other skeletal muscle tissue cell types, might be of importance for guidance of progenitor cells in muscle development and repair processes.

The muscle tissue immunohistochemistry experiments confirmed the presence of cells expressing typical TC protein markers, such as c-kit, caveolin-1 and vimentin [38], in the muscle interstitium. Even though both quiescent and activated satellite cells might express caveolin-1 as well [63], their clear different location, adherent to the sarcolemma, avoids the confusion with TCs.

By TEM, we showed evidence of shed vesicles and exosomes originating from Tps and immunohistochemistry proved that TCs express VEGF, in agreement with our previous observation in rat myocardium [59]. TCs might be involved in other signalling pathways as well, such as Wnt and Notch, involved in satellite cell fate regulation [64–66].

TCs and skeletal muscle stem cells

Muscle satellite cells constitute a reservoir of muscle progenitors, which can both self-renew and, under proper stimulation, differentiate and migrate to replace functional myocytes [1, 67]. However, a non-satellite, interstitial myogenic cell niche has been recently demonstrated as well [68], and even other cell types, such as bone marrow stem cells or pericytes, were suggested to have a myogenic potential under controlled conditions [69–71]. All muscle progenitor cells appear heterogeneous from the phenotypical point of view, depending upon their fate of recruitment or renewal [27, 58, 72–76]. In agreement with these reports, in this study we brought evidence of a non-satellite (resident) progenitor stem cell niche, where TCs and progenitor interstitial cells closely interact. We demonstrated as well that Tps are found in the vicinity of satellite cells. These intimate contacts of TCs with both types of muscle stem cells might indicate a mandatory cooperation during the recruitment and differentiation processes, as previously shown in other tissues [36].

In conclusion we report that TCs are present in the skeletal muscle interstitium and seem to connect all type of cells present in the muscular tissue. Because of their unique long-distance connection attributes, TCs might play an essential part in integrating signals for skeletal muscle fibres regulation and regeneration. TCs might support paracrine signalling with trophic factors (such as VEGF) for small vessels and scaffold guidance for progenitor (both satellite and non-satellite) cells which undergo migration and differentiation after stimulation.

Acknowledgments

This paper is supported by the Sectorial Operational Programme Human Resources Development (SOP HRD), financed from the European Social Fund and by the Romanian Government under the contract number POSDRU/89/1.5/S/64109 and by the Executive Unit for Financing Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation—Romania (UEFISCDI), Program 4 (Partnerships in Priority Domains), Grant No. 42133/2008.

We thank Professor Sawa Kostin (Bad Neuheim, Germany) for his constant help and especially for confocal microscopy analysis and image processing (Fig. 9 C, D).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kuang S, Gillespie MA, Rudnicki MA. Niche regulation of muscle satellite cell self-renewal and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rennie MJ, Phillips S, Smith K. Reliability of results and interpretation of measures of 3-methylhistidine in muscle interstitium as marker of muscle proteolysis. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1380–1. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90782.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perdiguero E, Sousa-Victor P, Ballestar E, et al. Epigenetic regulation of myogenesis. Epigenetics. 2009;4:541–50. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.8.10258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison JI, Borg P, Simon A. Plasticity and recovery of skeletal muscle satellite cells during limb regeneration. FASEB J. 2010;24:750–6. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-134825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beauchamp JR, Heslop L, Yu DS, et al. Expression of CD34 and Myf5 defines the majority of quiescent adult skeletal muscle satellite cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1221–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asakura A, Komaki M, Rudnicki M. Muscle satellite cells are multipotential stem cells that exhibit myogenic, osteogenic, and adipogenic differentiation. Differentiation. 2001;68:245–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2001.680412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maier A, Zhou Z, Bornemann A. The expression profile of myogenic transcription factors in satellite cells from denervated rat muscle. Brain Pathol. 2002;12:170–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2002.tb00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukada S, Higuchi S, Segawa M, et al. Purification and cell-surface marker characterization of quiescent satellite cells from murine skeletal muscle by a novel monoclonal antibody. Exp Cell Res. 2004;296:245–55. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gopinath SD, Rando TA. Stem cell review series: aging of the skeletal muscle stem cell niche. Aging Cell. 2008;7:590–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rudnicki MA, Le Grand F, McKinnell I, et al. The molecular regulation of muscle stem cell function. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:323–31. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins CA, Gnocchi VF, White RB, et al. Integrated functions of Pax3 and Pax7 in the regulation of proliferation, cell size and myogenic differentiation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lepper C, Conway SJ, Fan CM. Adult satellite cells and embryonic muscle progenitors have distinct genetic requirements. Nature. 2009;460:627–31. doi: 10.1038/nature08209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biressi S, Rando TA. Heterogeneity in the muscle satellite cell population. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dodson MV, Hausman GJ, Guan L, et al. Skeletal muscle stem cells from animals I. Basic cell biology. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:465–74. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill R, Hitchins L, Fletcher F, et al. Sulf1A and HGF regulate satellite-cell growth. Cell Sci. 2010;123:1873–83. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ieronimakis N, Balasundaram G, Rainey S, et al. Absence of CD34 on murine skeletal muscle satellite cells marks a reversible state of activation during acute injury. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang JS, Krauss RS. Muscle stem cells in developmental and regenerative myogenesis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:243–8. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328336ea98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell KJ, Pannérec A, Cadot B, et al. Identification and characterization of a non-satellite cell muscle resident progenitor during postnatal development. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:257–66. doi: 10.1038/ncb2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ono Y, Boldrin L, Knopp P, et al. Muscle satellite cells are a functionally heterogeneous population in both somite-derived and branchiomeric muscles. Dev Biol. 2010;337:29–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bach AD, Arkudas A, Tjiawi J, et al. A new approach to tissue engineering of vascularized skeletal muscle. J Cell Mol Med. 2006;10:716–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2006.tb00431.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Polykandriotis E, Arkudas A, Euler S, et al. Prevascularisation strategies in tissue engineering. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38:217–23. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polykandriotis E, Horch RE, Arkudas A, et al. Intrinsic versus extrinsic vascularization in tissue engineering. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;585:311–26. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-34133-0_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klumpp D, Horch RE, Kneser U, et al. Engineering skeletal muscle tissue-new perspectives in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2622–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooks NE, Cadena SM, Vannier E, et al. Effects of resistance exercise combined with essential amino acid supplementation and energy deficit on markers of skeletal muscle atrophy and regeneration during bed rest and active recovery. Muscle Nerve. 2010;42:927–35. doi: 10.1002/mus.21780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polykandriotis E, Popescu LM, Horch RE. Regenerative medicine: then and now —an update of recent history into future possibilities. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2350–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01169.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi CA, Pozzobon M, De Coppi P. Advances in musculoskeletal tissue engineering: moving towards therapy. Organogenesis. 2010;6:167–72. doi: 10.4161/org.6.3.12419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sancricca C, Mirabella M, Gliubizzi C, et al. Vessel-associated stem cells from skeletal muscle: From biology to future uses in cell therapy. World J Stem Cells. 2010;2:39–49. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v2.i3.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ten Broek RW, Grefte S, Von den Hoff JW. Regulatory factors and cell populations involved in skeletal muscle regeneration. J Cell Physiol. 2010;224:7–16. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young AP, Wagers AJ. Pax3 induces differentiation of juvenile skeletal muscle stem cells without transcriptional upregulation of canonical myogenic regulatory factors. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:2632–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.061606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suciu L, Popescu LM, Gherghiceanu M, et al. Telocytes in human term placenta: morphology and phenotype. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;192:325–39. doi: 10.1159/000319467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suciu L, Nicolescu MI, Popescu LM. Cardiac telocytes: serial dynamic images in cell culture. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2687–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinescu ME, Gherghiceanu M, Suciu L, et al. Telocytes in pleura: two- and three-dimensional imaging by transmission electron microscopy. Cell Tissue Res. 2011;343:389–97. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-1095-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popescu LM, Gherghiceanu M, Manole CG, et al. Cardiac renewing: interstitial Cajal-like cells nurse cardiomyocyte progenitors in epicardial stem cell niches. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:866–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kostin S, Popescu LM. A distinct type of cell in myocardium: interstitial Cajal-like cells (ICLC) J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:295–308. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gherghiceanu M, Popescu LM. Cardiomyocyte precursors and telocytes in epicardial stem cell niche: electron microscope images. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:871–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01060.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popescu LM, Manole CG, Gherghiceanu M, et al. Telocytes in human epicardium. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2085–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01129.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gherghiceanu M, Manole CG, Popescu LM. Telocytes in endocardium: electron microscope evidence. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2330–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01133.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Popescu LM, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. TELOCYTES-a case of serendipity: the winding way from Interstitial Cells of Cajal (ICC), via Interstitial Cajal-Like Cells (ICLC) to TELOCYTES. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:729–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01059.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Popescu LM, Gherghiceanu M, Kostin S. Telocytes and heart renewing. In: Wang P, Kuo CH, Takeda N, et al., editors. Adaptation biology and medicine: Volume 6: Cell adaptations and challenges. New Delhi: Narosa; 2011. pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gherghiceanu M, Popescu LM. Heterocellular communication in the heart. Electron tomography of telocyte-myocyte junctions. J Cell Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01299.x. , in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bani D, Formigli L, Gherghiceanu M, et al. Telocytes as supporting cells for myocardial tissue organization in developing and adult heart. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2531–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01119.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kostin S. Myocardial telocytes: a specific new cellular entity. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1917–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01111.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eyden B, Curry A, Wang G. Stromal cells in the human gut show ultrastructural features of fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells but not myofibroblasts. J Cell Mol Med. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01132.x. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01132.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Winter EM, Poelmann RE. Epicardium-derived cells (EPDCs) in development, cardiac disease and repair of ischemia. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1056–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Bani D. Relationships between telocytes and cardiomyocytes during pre- and post natal life. J Cell Mol Med D. 2010;14:1061–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tommila M. Granulation tissue formation. The effect of hydroxyapatite coating of cellulose on cellular differentiation. PhD Thesis, University of Turku, Finland; 2010.

- 47.Zhou J, Zhang Y, Wen X, et al. Telocytes accompanying cardiomyocyte in primary culture: two- and three-dimensional culture environment. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:2641–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gevaert T, De Vos R, Everaerts W, et al. Characterization of upper lamina propria interstitial cells in bladders from patients with neurogenic detrusor overactivity and bladder pain syndrome. J Cell Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01262.x. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01262.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kostin S. Types of cardiomyocyte death and clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.049. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Radenkovic G. Two patterns of development of interstitial cells of Cajal in the human duodenum. J Cell Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01287.x. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Limana F, Capogrossi MC, Germani A. The epicardium in cardiac repair: from the stem cell view. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129:82–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Carmona IC, Bartolomé MJ, Escribano CJ. Identification of telocytes in the lamina propria of rat duodenum: transmission electron microscopy. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cantarero I, Luesma MJ, Junquera C. The primary cilium of telocytes in the vasculature: electron microscope imaging. J Cell Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01312.x. , in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Russell JL, Goetsch SC, Gaiano NR, et al. A dynamic notch injury response activates epicardium and contributes to fibrosis repair. Circ Res. 2011;108:51–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang YH, Zhang GW, Gu TX, et al. Exogenous basic fibroblast growth factor promotes cardiac stem cell-mediated myocardial regeneration after miniswine acute myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32834523f8. 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32834523f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu J, Li J, Zhang N, et al. Stem cell-based therapies in ischemic heart diseases: a focus on aspects of microcirculation and inflammation. Basic Res Cardiol. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00395-011-0168-x. 10.1007/s00395-011-0168-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cismasiu VB, Radu E, Popescu LM. R-193 expression differentiates telocytes from other stromal cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01325.x. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jankowski RJ, Haluszczak C, Trucco M, et al. Flow cytometric characterization of myogenic cell populations obtained via the preplate technique: potential for rapid isolation of muscle-derived stem cells. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:619–28. doi: 10.1089/104303401300057306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Popescu LM. Telocytes and stem cells: a tandem in cardiac regenerative medicine. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18:94. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark MG, Wallis MG, Barrett EJ, et al. Blood flow and muscle metabolism: a focus on insulin action. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;284:E241–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00408.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mathew SJ, Hansen JM, Merrell AJ, et al. Connective tissue fibroblasts and Tcf4 regulate myogenesis. Development. 2011;138:371–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.057463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zammit PS, Partridge TA, Yablonka-Reuveni Z. The skeletal muscle satellite cell: the stem cell that came in from the cold. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1177–91. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6R6995.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gnocchi VF, White RB, Ono Y, et al. Further characterisation of the molecular signature of quiescent and activated mouse muscle satellite cells. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brack AS, Conboy IM, Conboy MJ, et al. A temporal switch from notch to Wnt signaling in muscle stem cells is necessary for normal adult myogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:50–9. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuang S, Kuroda K, Le Grand F, et al. Asymmetric self-renewal and commitment of satellite stem cells in muscle. Cell. 2007;129:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsivitse S. Notch and Wnt signaling, physiological stimuli and postnatal myogenesis. Int J Biol Sci. 2010;6:268–81. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Biressi S, Rando TA. Heterogeneity in the muscle satellite cell population. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:845–54. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mitchell KJ, Pannérec A, Cadot B, et al. Identification and characterization of a non-satellite cell muscle resident progenitor during postnatal development. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:257–66. doi: 10.1038/ncb2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.LaBarge MA, Blau HM. Biological progression from adult bone marrow to mononucleate muscle stem cell to multinucleate muscle fiber in response to injury. Cell. 2002;111:589–601. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doyonnas R, LaBarge MA, Sacco A, et al. Hematopoietic contribution to skeletal muscle regeneration by myelomonocytic precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405361101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dellavalle A, Sampaolesi M, Tonlorenzi R, et al. Pericytes of human skeletal muscle are myogenic precursors distinct from satellite cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:255–67. doi: 10.1038/ncb1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee JY, Qu-Petersen Z, Cao B, et al. Clonal isolation of muscle-derived cells capable of enhancing muscle regeneration and bone healing. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:1085–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.5.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Torrente Y, Tremblay JP, Pisati F, et al. Intraarterial injection of muscle-derived CD34(+)Sca-1(+) stem cells restores dystrophin in mdx mice. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:335–48. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Asakura A, Seale P, Girgis-Gabardo A, et al. Myogenic specification of side population cells in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:123–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tamaki T, Okada Y, Uchiyama Y, et al. Skeletal muscle-derived CD34+/45− and CD34−/45− stem cells are situated hierarchically upstream of Pax7+ cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:653–67. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Waddell JN, Zhang P, Wen Y, et al. Dlk1 is necessary for proper skeletal muscle development and regeneration. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]