Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a large family of small non-coding RNAs which negatively control gene expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. The number of miRNAs identified is growing rapidly and approximately one-third is expressed in the brain where they have been shown to affect neuronal differentiation, synaptosomal complex localization and synapse plasticity, all functions thought to be disrupted in schizophrenia. Here we investigated the expression of 667 miRNAs (miRBase v.13) in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia (SZ, N=35) and bipolar disorder (BP, N=35) using a real-time PCR-based Taqman Low Density Array (TLDA). After extensive QC steps, 441 miRNAs were included in the final analyses. At a FDR of 10%, 22 miRNAs were identified as being differentially expressed between cases and controls, 7 dysregulated in SZ and 15 in BP. Using in silico target gene prediction programs, the 22miRNAs were found to target brain specific genes contained within networks overrepresented for neurodevelopment, behavior, and SZ and BP disease development.

In an initial attempt to corroborate some of these predictions, we investigated the extent of correlation between the expressions of hsa-mir-34a, -132 and -212 and their predicted gene targets. mRNA expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD) and metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) was measured in the SMRI sample. Hsa-miR-132 and -212 were negatively correlated with TH (p=0.0001 and 0.0017) and with PGD (p=0.0054 and 0.017, respectively).

Keywords: MiRNA, Schizophrenia, Bipolar, Gene, Expression, TLDA

1. Introduction

Both schizophrenia (SZ, MIM 181500) and bipolar disorder (BP, MIM 125480) are common and debilitating psychiatric illnesses with a lifetime prevalence of 0.5–1% and 0.8–2.6% respectively. The etiology of SZ and BP is currently unknown, however in conjunction with environmental and developmental factors (Jablensky et al., 1992; Kendler et al., 1994; Kendler and Diehl, 1993), consistent evidence for a substantial genetic component (Kato et al., 2005) has been shown, with some shared between both diseases (Berrettini, 2003; Purcell et al., 2009a).

Protein-coding genes have long been the focus of research in disease genetics, but efforts to identify replicable protein-coding risk loci in SZ (Shi et al., 2009a; Stefansson et al., 2009b) and BP (Sklar et al., 2008) remain elusive. Current GWAS studies have also been unable to establish a uniform set of protein-coding genes exhibiting a clear etiology in disease (Purcell et al., 2009b; Shi et al., 2009b; Stefansson et al., 2009a). Additionally, genetic association does not appear to reflect DNA variants with any obvious effect on protein structure (Bray, 2008) for several of the best supported SZ susceptibility genes identified to date (e.g. DTNBP1 and NRG1).

MiRNAs are a large family of small non-coding RNAs which negatively control gene expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Lai, 2002). Most miRNAs are processed from a Pol II transcript called a primary miRNA (pri-miRNA), which is further processed to a smaller hairpin-like structure called a precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA). The terminal loop of the pre-miRNA is then cleaved, generating a miRNA/miRNA* duplex and one strand is preferentially loaded into the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC) (Filipowicz et al., 2008) leading to mRNA degradation and/or translational repression. MiRNAs control mRNA stability and translation by binding to sequence motifs in the 3′-UTR of target mRNAs (Valencia-Sanchez et al., 2006). This binding does not require complete complementarity except for nucleotides 2–8 (the “seed region”) at the miRNA's 5′ end. Although the majority of miRNA/ mRNA interactions require perfect complementarity at the seed region, there are some exceptions to this rule, which complicates miRNA target predictions (Lai, 2004).

Microarray studies have revealed that individual miRNAs can affect the expression of multiple genes (Krichevsky et al., 2006), suggesting that miRNAs can have pleiotropic effects on cellular processes. A growing number of miRNAs are discovered every year (Griffiths-Jones et al., 2006) and approximately one-third is expressed in the brain (Sempere et al., 2004) where they have been shown to be involved in maintaining brain function (Fiore et al., 2008). In vitro studies demonstrate that miRNAs are localized to the synaptosomal complex (Lugli et al., 2005) where they affect neuronal differentiation (Vo et al., 2005) and modulate synapse plasticity (Schratt et al., 2006), both of which have been implicated in SZ and BP (Eastwood and Harrison, 2001; Vawter et al., 2002). Thus, miRNAs are likely candidates in neurodegenerative disorders (Kuss and Chen, 2008) and recent studies have attempted to evaluate the impact of miRNAs in SZ etiology at both genetic (Rogaev, 2005; Hansen et al., 2007; Burmistrova et al., 2007) and expression (Burmistrova et al., 2007; Beveridge et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2007) levels.

Postmortem brain tissue has been successfully used to identify transcriptional dysregulation of candidate genes in SZ and BP (Harrison and Weinberger, 2005). Here, we evaluated the expression of 667 miRNAs in the postmortem prefrontal cortex of patients with SZ and BP disorder.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Postmortem brain tissue

The Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI) provided 200 mg of postmortem brain tissue from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, Brodmann's area 46) (Torrey et al., 2000). The sample demographics are described in Suppl. Table 1. Exclusion criteria included: (1) brain pathology, (2) history of pre-existing CNS disease, (3) poor RNA quality, (4) IQ<70, (5) age<30 and (6) substance abuse within one year of death.

2.2. RNA isolation and quantification

Total RNA containing the small RNA fraction was isolated from 100 mg of tissue using the miRvana-Paris Kit (Ambion, Austin, Texas) following manufacturer's recommendations. RNA quality and concentration were measured on the 21000 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). Average RNA integrity number (RIN) was 7.2. The tissue for one BP sample was not received and 1 CON sample gave poor RNA quality, both of which were excluded from further analyses.

2.3. MiRNA reverse transcription

cDNA synthesis for TLDA was performed according to manufacturer's recommendation (ABI). Briefly, RNA was reverse transcribed using the MicroRNA reverse transcription kit (ABI) in combination with the stem-loop Megaplex primer pool (ABI). 3 µl of total RNA (33.3 ng/µl) was combined with 0.8 µl RT primer mix (10×), 0.8 µl RT buffer (10×), 1.5 µl MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase (10 U/µl), 0.2 µl dNTPs with dTTP (0.5 mM each), 0.9 µl MgCl2 (3 mM) and 0.1 µl RNase inhibitor (0.25 U/µl) in a total reaction volume of 7.5 µl. Reactions were run on an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Westbury, NY) in a 384-well plate for 40 cycles at 16 °C for 2 min, 42 °C for 1 min, 50 °C for 1 s, and 85 °C for 5 min.

cDNA synthesis for the single tube miRNA reactions was performed using the TaqMan MicroRNA reverse transcription kit (ABI). 10 ng of RNA (2 ng/µl) was combined with 3.0 µl 5× RT primer, 0.15 µl 100 mM dNTPs, 1.0 µl MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase (50 U/µl), 1.5 µl 10× RT buffer and 0.19 µl RNase inhibitor (20 U/µl) in a total reaction volume of 15 µl. Reactions were run on an Eppendorf Mastercycler (Eppendorf) in a 96-well plate for 40 cycles at 16 °C for 30 min, 42 °C for 30 min and 85 °C for 5 min.

2.4. MiRNA expression detection

Prior to detecting miRNA expression, the cDNA for the TLDA array was pre-amplified following ABI's recommendations, allowing for increased detection sensitivity while preserving the miRNA (Cogswell et al., 2008b; Mestdagh et al., 2008; Tang et al., 2006) expression profile (Suppl. Fig. 1). The reactions were diluted with 75 µl of 0.1× TBE and stored at −20 °C. 9 µl of product and 450 µl of TaqMan PCR Master Mix, was combined with 441 µl nuclease free water, mixed and centrifuged for 30 s. 100 µl was loaded into each port of the appropriate 384 well TLDA array, centrifuged twice at 1200 rpm in a Sorvall Legend centrifuge (Thermo Scientific, USA), and sealed with a micro-fluidic card staker (ABI). The arrays were run on the 7900HT Real-Time PCR System according to manufacturer's protocol. Raw Cq values (RDML guidelines, http://www.rdml.org (Lefever et al., 2009)) were calculated using the SDS software v.2.3 with automatic baseline settings at a threshold of 0.2.

The single tube miRNA expressions were detected using TaqMan chemistry according to the manufacturer's protocol (ABI). 1.33 µl of cDNA (diluted 1:15) was combined with 1.0 µl 20× TaqMan MicroRNA assay and 10.0 µl 2× TaqMan Universal PCR MasterMix, No AmpErase UNG in a final volume of 20 µl. The reactions were run in triplicate in a 384-well plate on the 7900HT Real-Time PCR System according to manufacturer's recommendations (ABI).

2.5. MiRNA PCR expression normalization

Under our experimental conditions, the three reference genes contained on the A and B TLDA arrays did not maintain a consistent ratio across samples (Suppl. Fig. 2). Therefore, we normalized our data using the median polish procedure (Bolstad et al., 2003), a method similar to that employed by others to evaluate global miRNA expression (Abu-Elneel et al., 2008). A more detailed description of the method is given in the Supplementary (S2a) material.

2.6. Quality control (QC)

Potential technical artifacts, such as plate effects (Sundberg et al., 2006), were evaluated by plotting the sample profile correlations which were invariant under this normalization. Two bands of low correlations were observed, which we interpreted as plate effects independent of diagnosis (Suppl. Fig. 3). Samples falling within these bands were excluded from further analyses as they also clustered separately from the main group (Suppl. Fig. 4). Thus, the final sample was reduced to 29 SZ, 27 BP and 31 CONT.

2.7. Gene expression

mRNA samples (300 ng) were reverse transcribed into cDNA using the high capacity cDNA Kit from ABI following the manufacturer's instructions. TH, PGD and GRM3 gene expressions were measured by Taqman chemistry on the 7900HT instrument according to the manufacturer's recommendation and normalized against the IPO8 reference control using the 2−ΔΔCt algorithm.

2.8. Statistical methods

The primary analyses were conducted using the rlm function in the R open-source statistical language (www.r-project.org) and the exploratory analyses were conducted using Robust Multiple Regression with Huber's method as implemented in the NCSS (http://www.ncss.com) software package. MiRNA variance was estimated using an F-test with corrected degrees of freedom and the Spearman (ρ) coefficient was used to estimate correlations of miRNA expressions. Correction for multiple testing was accomplished using the Benjamini–Hochberg (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) False Discovery Rate (FDR) at 10%. A complete list of p-values and respective q-values for the entire miRNA data set is provided as well (Suppl. Table. 2). The significantly expressed SZ and BP miRNAs were correlated using Spearman ρ coefficient.

The single tube miRNA expression data were log transformed or raised to the power of 1/3 (Suppl. Table 3) to approximate a normal distribution and analyzed within a multiple regression framework with disease as the main factor and pH and sex included as covariates. Gene targets for the differentially expressed miRNAs were predicted in house by the miRanda algorithm (Enright et al., 2004) (V.3) using default parameters. For the correlation analysis, the expression of miRNAs and their respective gene targets were normalized and log transformed or raised to the power of 1/3 (Suppl. Table 4). The expression values were fitted into an analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA) model with pH, age, RIN, sex and disease status as covariates. The effect of these potential covariates was regressed out and the residuals were then correlated using the Pearson product moment.

3. Results

3.1. Overall performance

Each individual in the SMRI sample was evaluated for the expression of 667 miRNAs. Of these, 226 miRNAs were excluded from further analyses due to lack of amplification, very low expression (Cq>35), or poor amplification efficiency across samples (missing expression values ≥80%). 441 miRNAs were included in all subsequent analyses (Suppl. Table 5) and based on their average expression were arbitrarily classified as highly (Cq 14–20), moderately (Cq 21–26), or low (Cq 27–34) expressed (Suppl. Table 6). Being a global miRNA evaluation, it is reasonable to expect that not all miRNAs are brain expressed.

3.2. SMRI demographics

Together with disease status, the SMRI provided additional information regarding potential confounders described in Supplementary S2b. Upon inspection, only PMI, RI and antipsychotics showed deviation from a normal distribution, which were log transformed to approximate normality. In our analyses, none of the covariates showed consistent effects on miRNA expression. When fitting a regression model to a small sample size, the number of estimated parameters cannot be large, therefore in all analyses, only sex and pH were included as technical covariates.

3.3. Detection of differentially expressed miRNAs in SZ and BP cases

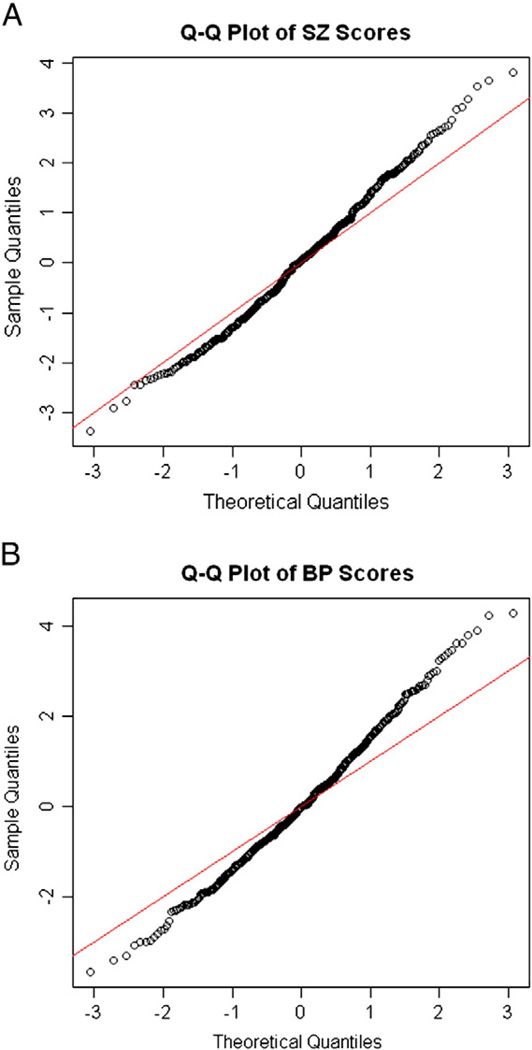

Our main objective was to evaluate expression differences between SZ and BP cases and controls for all known human miRNAs using the TLDA high throughput real-time qPCR approach. The T-score distribution from the linear model showed deviation from the expected normal distribution (Fig. 1), and after controlling the FDR at 10%, 22 miRNAs were identified as significantly dysregulated in SZ and BP (Table 1). Notably, hsa-miR-7, -212 and -132, which were previously reported to be dysregulated in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with SZ and schizoaffective disorder (Perkins et al., 2007), were also dysregulated in our sample.

Fig. 1.

Q–Q plots of the T-scores distribution within the SZ group. 1B. Q–Q plots of the T-scores distribution within the BP group. T-scores are obtained from the linear model.

Table 1.

Significantly expressed miRNAs in the SZ and BP groups compared to controls at FDR of 10%. The miRNAs highlighted in the SZ group were reported in previous studies. See text for more details. The negative values of the T-scores reflect up- or down-regulation of specific miRNA expression.

| Status | MiRNA | Aver. Cq | β(i) | SE | T-value | P-value | Q-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SZ | hsa-miR-34a | 21.82 | 0.385 | 0.093 | 4.12 | 0.00004 | 0.018 |

| SZ | hsa-miR-132* | 29.14 | 0.364 | 0.092 | 3.98 | 0.00016 | 0.024 |

| SZ | hsa-miR-132 | 17.47 | 0.212 | 0.053 | 3.97 | 0.00016 | 0.024 |

| SZ | hsa-miR-212 | 23.04 | 0.232 | 0.064 | 3.65 | 0.00047 | 0.048 |

| SZ | hsa-miR-544 | 31.35 | 0.839 | 0.243 | 3.46 | 0.00054 | 0.048 |

| SZ | hsa-miR-7 | 23.1 | 0.241 | 0.069 | 3.50 | 0.00078 | 0.054 |

| SZ | hsa-miR-154* | 26.31 | 0.511 | 0.153 | 3.33 | 0.00086 | 0.054 |

| BP | hsa-miR-504 | 24 | 0.710 | 0.169 | 4.19 | 0.00003 | 0.007 |

| BP | hsa-miR-454* | 30.53 | −0.925 | 0.226 | −4.10 | 0.00004 | 0.007 |

| BP | hsa-miR-29a | 17.64 | −0.297 | 0.073 | −4.07 | 0.00005 | 0.007 |

| BP | hsa-miR-520c-3p | 30.11 | −0.617 | 0.165 | −3.75 | 0.00018 | 0.020 |

| BP | hsa-miR-140-3p | 25.14 | −0.473 | 0.137 | −3.47 | 0.00053 | 0.047 |

| BP | hsa-miR-145* | 26.6 | 0.572 | 0.171 | 3.35 | 0.00080 | 0.052 |

| BP | hsa-miR-767-5p | 26.87 | −0.329 | 0.100 | −3.29 | 0.00102 | 0.052 |

| BP | hsa-miR-22* | 23.19 | 0.465 | 0.142 | 3.27 | 0.00106 | 0.052 |

| BP | hsa-miR-145 | 17.83 | 0.571 | 0.183 | 3.13 | 0.00177 | 0.066 |

| BP | hsa-miR-874 | 21.9 | −0.391 | 0.125 | −3.12 | 0.00181 | 0.066 |

| BP | hsa-miR-133b | 24.98 | 0.359 | 0.116 | 3.11 | 0.00190 | 0.066 |

| BP | hsa-miR-154* | 26.31 | 0.501 | 0.162 | 3.10 | 0.00195 | 0.066 |

| BP | hsa-miR-32 | 29.18 | −0.724 | 0.235 | −3.08 | 0.00209 | 0.066 |

| BP | hsa-miR-573 | 29.03 | −0.939 | 0.308 | −3.05 | 0.00227 | 0.067 |

| BP | hsa-miR-889 | 24.83 | 0.433 | 0.147 | 2.95 | 0.00321 | 0.089 |

3.4. SZ cases

Seven miRNAs were differentially expressed in the SZ group. Of these, hsa-miR-34a, located on chromosome 1 (1p36.22), was the most significantly differentially expressed (p=0.00004) and in contrast to a previous study showing high expression (Lim et al., 2005), this miRNA was moderately expressed (average Cq=21.8). Hsa-miR-132 and -132* are processed from the same precursor and together with hsa-miR-212, forma cluster located on the reverse strand of chromosome 17 (17p13.3). Hsa-mir-132 and -212 were previously reported to be expressed in brain and our data confirm this observation (Lu et al., 2005). Hsa-miR-132 was highly expressed (average Cq=17.5) and hsa-mir-212 was moderately expressed at an (average Cq of 23). Both miRNAs were highly correlated (Spearman's ρ=0.87), supporting previous observations for coordinated expression of clustered miRNAs (Lee and Kim, 2004; Lee et al., 2004; Sempere et al., 2004). Hsa-miR-132* however, was expressed at a lower level (average Cq=27.18) and was less correlated with hsa-miR-132 (Spearman's ρ=0.65) and hsa-miR-212 (ρ=0.47). Hsa-miR-7 consists of three members located on three chromosomes; hsa-miR-7-1 (9q21.32), hsa-miR-7-2 (15q21.6) and hsa-miR-7-3 (19p13.3). The hsa-miR-7 family showed moderate expression (average Cq=23.1), but since the mature sequence of these three miRNAs is identical, individual expression of each member could not be separated. Finally, hsa-miR-544 was low (Cq=31.35) and hsa-miR-154* was moderately (Cq=26.31) expressed. Hsa-miR-154* was the only miRNA showing expression differences in both SZ and BP.

3.5. BP cases

In the BP group, 15 miRNAs were observed to be differentially expressed. Seven were over-expressed and 8 were under-expressed (Table 1). The over-expressed miRNAs were all moderately to highly expressed and showed significant correlation with each other (Table 2A). In contrast, the under-expressed miRNAs were moderately to low expressed and did not show any significant inter-correlations (Table 2B). Of all correlated miRNAs, only two are known to cluster together, hsa-miR-154* and -889 on chr.14 (14q32.2). However in contrast to the clustered miRNAs observed in the SZ group, hsa-miR-154* and -889 were only modestly correlated with each other (Spearman's ρ=0.35).

Table 2.

| A | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation matrix of miRNAs over-expressed in the BP group. Spearman's p coefficients in bold are statistically significant at p<0.05. | |||||||

| Variables | hsa-miR-504 | hsa-miR-145 | hsa-miR-145* | hsa-miR-22* | hsa-miR-133b | hsa-miR-154* | hsa-miR-889 |

| hsa-miR-504 | 1 | 0.420 | 0.503 | 0.608 | 0.512 | 0.611 | 0.633 |

| hsa-miR-145 | 0.420 | 1 | 0.840 | 0.427 | 0.550 | 0.230 | 0.276 |

| hsa-miR-145* | 0.503 | 0.840 | 1 | 0.493 | 0.451 | 0.397 | 0.364 |

| hsa-miR-22* | 0.608 | 0.427 | 0.493 | 1 | 0.344 | 0.554 | 0.550 |

| hsa-miR-133b | 0.512 | 0.550 | 0.451 | 0.344 | 1 | 0.141 | 0.485 |

| hsa-miR-154* | 0.611 | 0.230 | 0.397 | 0.554 | 0.141 | 1 | 0.355 |

| hsa-miR-889 | 0.633 | 0.276 | 0.364 | 0.550 | 0.485 | 0.355 | 1 |

| B | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation matrix of miRNAs under-expressed in BP group. Spearman's p coefficients in bold are statistically significant at p<0.05. | ||||||||

| Variables | hsa-miR-140-3p | hsa-miR-29a | hsa-miR-32 | hsa-miR-874 | hsa-miR-454* | hsa-miR-520c-3p | hsa-miR-573 | hsa-miR-767-5p |

| hsa-miR-140-3p | 1 | 0.127 | 0.288 | 0.062 | 0.392 | 0.051 | −0.067 | −0.057 |

| hsa-miR-29a | 0.127 | 1 | 0.163 | 0.017 | 0.244 | 0.165 | −0.067 | 0.245 |

| hsa-miR-32 | 0.288 | 0.163 | 1 | 0.012 | 0.296 | −0.226 | −0.079 | −0.077 |

| hsa-miR-874 | 0.062 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 1 | −0.057 | 0.160 | 0.194 | 0.207 |

| hsa-miR-454* | 0.392 | 0.244 | 0.296 | −0.057 | 1 | −0.335 | −0.328 | 0.076 |

| hsa-miR-520c-3p | 0.051 | 0.165 | −0.226 | 0.160 | −0.335 | 1 | 0.403 | −0.149 |

| hsa-miR-573 | −0.067 | −0.067 | −0.079 | 0.194 | −0.328 | 0.403 | 1 | −0.171 |

| hsa-miR-767-5p | −0.057 | 0.245 | −0.077 | 0.207 | 0.076 | −0.149 | −0.171 | 1 |

3.6. TLDA validation

All 22 miRNAs differentially expressed from the TLDA approach were validated in single tube real-time PCR reactions. One miRNA, hsa-miR-573, was not amplified and therefore excluded from the validation analyses. The remaining 21 miRNA expressions were normalized by the 2−ΔΔCt approach using RNU48 as an endogenous control. Nine miRNAs were successfully validated, 5 in SZ and 4 in BP (Suppl. Table 7). Interestingly, 3 of the SZ specific miRNAs were also significantly expressed in the BP group and 2 of the BP specific miRNAs were also significantly expressed in the SZ group. This observation is not surprising considering the proposed common etiology between SZ and BP disorders (Berrettini, 2003; Purcell et al., 2009a). The discrepancy between the multiplex and singly validated miRNA data could be explained by biological (heterogeneity) or technical (PCR conditions or pre-amplification) differences. Additional expression studies will be needed to address such issues. However, many of the validated miRNAs reported here have also been previously reported in other studies using different platforms and/ or samples.

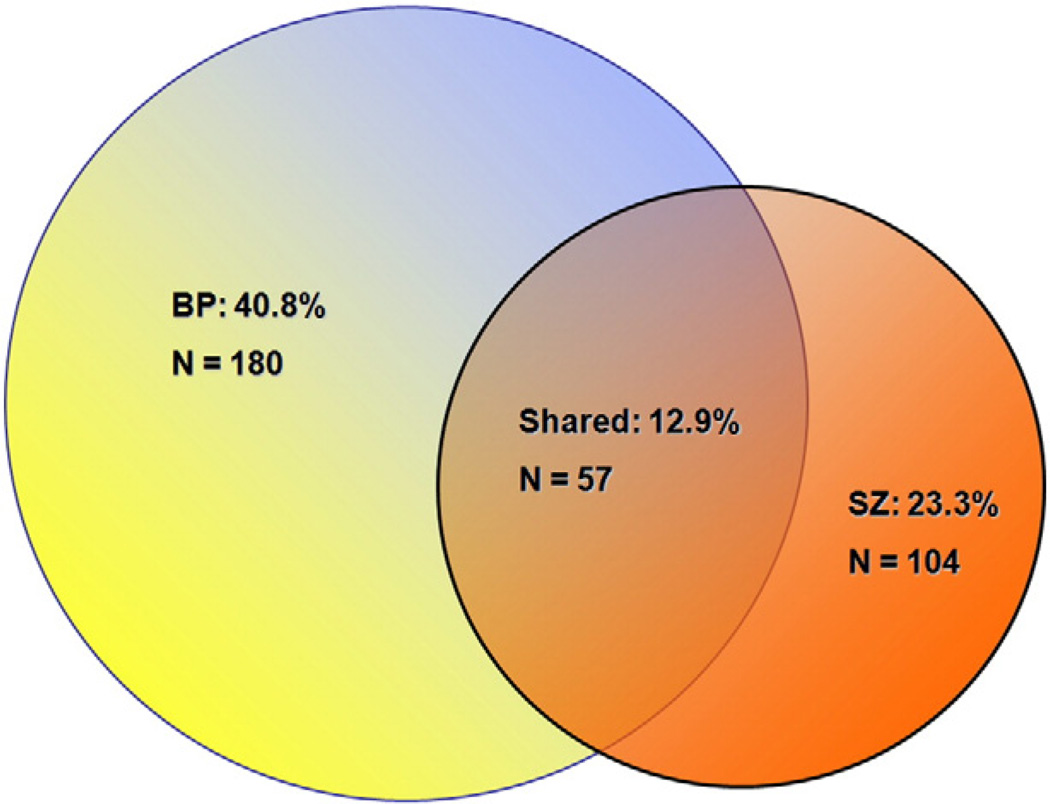

3.7. Analysis of miRNA variances

Although miRNAs tend to be dysregulated among individuals with SZ or BP, a limited number of miRNAs (22/441 or 5%) demonstrated a consistent direction of altered expression, e.g. the same miRNA following a similar direction of expression. This is not surprising considering the multigenic etiology of SZ and BP. Moreover, when miRNA variances between groups were compared, many of the miRNAs showing significant variance differences (Suppl. Table 8) were present in both disease groups (Fig. 2), thereby supporting the shared genetic risk in SZ and BP that others have observed (Berrettini, 2003; Purcell et al., 2009a).

Fig. 2.

A Venn diagram showing the number of disease specific and shared miRNAs with significant variances for the two diagnostic groups.

3.8. Exploratory analyses

Exploratory analyses were performed to test changes in miRNA expression for disease duration (Dean et al., 2007), smoking (Zammit et al., 2003), suicide (Pompili et al., 2007), and antipsychotic treatment as these traits were previously shown to affect expression of SZ candidate genes. The only significant effect was observed for hsa-miR-193b* (p=0.00002) when suicide was analyzed in interaction with disease. Antipsychotic treatment did not show any systematic effect on miRNA expression with hsa-miR-218-2* (p=0.000012) expression affected in the BP group only. A probable explanation is that in the SMRI sample, antipsychotic treatment is reported as a generalized measure (fluphenazine equivalents). Since different drugs have different (if not opposing) affects on miRNA expression, the individual drug effect is likely to be confounded.

3.9. In silico analyses

Using miRanda (John et al., 2004) we identified 3171 predicted gene targets for the 5 validated miRNAs differentially expressed in the SZ group and 2666 predicted gene targets for the 4 validated miRNAs differentially expressed in the BP group (Suppl. Table 9A and 9B). The nature of these gene targets was then evaluated using the IPA web tool. In IPA, our gene dataset was used as the reference set to minimize experimental or literature bias. The most enriched functional group of genes amongst the differentially expressed miRNA targets (Suppl. Fig. 5A and 5B) were genes forming networks related to nervous system function and disease, including SZ and BP.

In an initial attempt to corroborate some of these predictions, we investigated the extent of correlation between the expressions of hsa-mir-34a, -132 and -212 and their predicted gene targets. We focused on these miRNAs because they were highly significant in our study and previous reports implicated the min SZ and autism. Based on miRanda and IPA, three disease relevant gene targets for hsa-miR-34a, -132 and -212 were tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) and phosphogluconate dehydrogenase (PGD). We measured the mRNA expression of TH, GRM3 and PGD in the SMRI postmortem sample and correlated these with their respective miRNAs: hsa-miR-34a with TH and PGD; hsa-miR-132 with TH and GRM3; and hsa-miR-212 with TH and GRM3. Since miRNAs primarily act to negatively regulate gene expression, miRNA over-expression should lead to downregulation of their gene targets (Wang and Wang, 2006) resulting in a negative correlation. Hsa-miR-34a did not show significant correlations with its predicted target genes. However, hsa-miR-132 was negatively correlated with TH, r= −0.41 (p=0.0001) and PGD, r=−0.29 (p=0.0054) and hsa-miR-212 with TH r=−0.35, (p=0.0017) and PGD r=−0.22, (p=0.017), respectively (Suppl. Fig. 6). Although PGD was not computationally predicted to be targeted by these two miRNAs, this observation reflects previous experimental studies demonstrating physical interaction between miRNA and genes that are not bioinformatically predicted as miRNA targets (Beitzinger et al., 2007).

4. Discussion

MiRNAs have key roles in regulating gene expression and brain development, and thus are likely genetic factors contributing to the etiology of psychiatric disorders. In this study, we conducted an evaluation of miRNA expression in postmortem tissues from SZ and BP cases. Of the 441 miRNAs analyzed, we identified 7 to be differentially expressed in SZ and 15 to be differentially expressed in BP, which constitutes ~5% of miRNAs studied. Similar observations were made in other studies of SZ (Perkins et al., 2007) and autistic (Abu-Elneel et al., 2008) cases. Although few miRNAs showed consistent unidirectional expression differences between cases and controls, we observed a large number of miRNAs with significant variance differences in SZ and BP, many of which were shared by both disease groups. Thus we, as others (Abu-Elneel et al., 2008; Perkins et al., 2005), argue that the development of SZ and BP is likely to reflect two classes of miRNAs: the first class consisting of miRNAs showing consistent unilateral expression across all cases in the disease groups, and the second class showing much greater individual variability of expression.

Several studies have attempted to address differential expression of miRNAs in the etiology of SZ. Perkins et al. (2007) were the first to evaluate miRNA expression in a postmortem brain sample consisting of 13 individuals with SZ and 2 individuals with schizoaffective disorder. They identified 16 miRNAs dysregulated in cases, two of which, hsa-miR-7 and -212, were also differentially expressed in our study. In two separate studies, Beveridge et al. (2008; 2009) observed 26 differentially expressed miRNAs in the DLPFC of SZ cases, including hsa-miR-7. In a fourth study of autistic cases (Abu-Elneel et al., 2008), 28 miRNAs were shown to be dysregulated across 9 autistic samples, including hsa-miR-7 and -132.

In addition to being dysregulated in SZ and autistic cases, hsa-miR-7 has been shown to be involved in the development of Parkinson's disorder by repressing the expression of alpha synuclein (α-Syn), a protein that accumulates in the nigral dopaminergic neurons (Junn et al., 2009). Hsa-miR-7 was also shown to be involved in the development of glioblastoma by repressing the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene and the AKT1 signaling pathway (Kefas et al., 2008). The repressing effect of hsa-miR-7 on AKT1 is noteworthy since AKT1 has been shown to be associated with BP (Toyota et al., 2003) and with SZ across multiple populations (Bajestan et al., 2006; Emamian et al., 2004; Ikeda et al., 2004; Schwab et al., 2005; Thiselton et al., 2008).

Hsa-miR-132 and -212 expressions have been reported to be dysregulated in Alzheimer's disease (Cogswell et al., 2008a), suggesting a broader impact of these miRNAs on diseases of brain development. The predicted hsa-miR-132 and miR-132* gene targets interact with genes known to be involved in SZ (GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and Dopamine receptor 1 (DRD1)). GRIN1, GRIN2A, and GRIN2B encode different subunits of the NMDA receptor, the dysfunction of which is a major etiological hypothesis of SZ pathophysiology (Javitt, 2007). BDNF mRNA levels have been shown to be significantly reduced in the DLPFC of schizophrenics (Weickert et al., 2003). DRD1 is thought to have a role in the regulation of cognitive functions in the DLPFC (Missale et al., 2006) and is also thought to be involved in the action of the atypical antipsychotic clozapine used in the treatment of schizophrenia (Stone et al., 2007).

Finally, several reports have linked CNVs to the genetic risk of SZ (Kirov et al., 2008; Stefansson et al., 2008; Stone et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2008). Using a database of genomic variants (http://projects.tcag.ca/variation/), we identified 7 miRNAs from our list of dysregulated miRNAs mapping to CNV regions (Suppl. Table 10). Although none of these CNVs on chromosomes 1, 9, and 17 have been reported to be associated with SZ, a robust relationship between disease (cancer) phenotype and miRNAs located in CNVs has been established (Zhang et al., 2006), suggesting that a possible association between CNVs and miRNAs differentially expressed in SZ and BP may exist as well.

5. Conclusions

In this study we evaluated 667 miRNAs, 441 of which showed reliable expression in the SMRI postmortem brain sample. This is the largest set of miRNAs evaluated to date, hence it is not surprising that we observed a greater number of miRNAs (two-thirds) to be expressed in brain than previously reported (Sempere et al., 2004). Twenty two miRNAs were found to be differentially expressed between cases and controls, three of which, hsa-miR-7, -132, and -212 were previously reported to be dysregulated in SZ. Furthermore, in silico predicted gene targets for these miRNAs were found to be overrepresented in networks relevant to SZ and BP disorders. Going further, we observed a negative correlation between the expression of miRNAs and their predicted gene targets, providing preliminary support for our computational predictions. Thus, miRNAs are likely to contribute to disease development by modulating expression of previously identified gene candidates for SZ and BP and our study provides additional evidence for miRNA involvement in the etiology of disease. To our knowledge, we are also the first to report differentially expressed miRNAs in BP disorder.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Ricardo Pastori for his helpful comments on this manuscript.

Role of funding source

Funding for this study was provided by SMRI grant (#08R-1959) to V.I.V.; SMRI had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. Funding for A.H.K. was provided by NIMH Research Training Grant in Psychiatric and Statistical Genetics (#2T32MH020030).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.schres.2010.07.002.

Footnotes

Contributors

A.H.K. and O. M. performed the experimental work. M.R., B.M., J.M. and E. G.C.J. undertook all statistical analyses and helped with their interpretation. V.W. performed the in silico analyses. VIV designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. B.P.R. and K.S.K. contributed to the final writing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Abu-Elneel K, Liu T, Gazzaniga FS, Nishimura Y, Wall DP, Geschwind DH, Lao K, Kosik KS. Heterogeneous dysregulation of microRNAs across the autism spectrum. Neurogenetics. 2008;9:153–161. doi: 10.1007/s10048-008-0133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajestan SN, Sabouri AH, Nakamura M, Takashima H, Keikhaee MR, Behdani F, Fayyazi MR, Sargolzaee MR, Bajestan MN, Sabouri Z, Khayami E, Haghighi S, Hashemi SB, Eiraku N, Tufani H, Najmabadi H, Arimura K, Sano A, Osame M. Association of AKT1 haplotype with the risk of schizophrenia in Iranian population. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:383–386. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitzinger M, Peters L, Zhu JY, Kremmer E, Meister G. Identification of human microRNA targets from isolated argonaute protein complexes. Rna Biology. 2007;4:76–84. doi: 10.4161/rna.4.2.4640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate — a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Berrettini W. Evidence for shared susceptibility in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C-Seminars in Medical Genetics. 2003;123C:59–64. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge NJ, Tooney PA, Carroll AP, Gardiner E, Bowden N, Scott RJ, Tran N, Dedova I, Cairns MJ. Dysregulation of miRNA 181b in the temporal cortex in schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1156–1168. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge NJ, Gardiner E, Carroll AP, Tooney PA, Cairns MJ. Schizophrenia is associated with an increase in cortical microRNA biogenesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2009 doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray NJ. Gene expression in the etiology of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34:412–418. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmistrova OA, Goltsov AY, Abramova LI, Kaleda VG, Orlova VA, Rogaev EI. MicroRNA in schizophrenia: genetic and expression analysis of miR-130b (22q 11) Biochemistry—Moscow. 2007;72:578–582. doi: 10.1134/s0006297907050161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell JP, Ward J, Taylor IA, Waters M, Shi YL, Cannon B, Kelnar K, Kemppainen J, Brown D, Chen C, Prinjha RK, Richardson JC, Saunders AM, Roses AD, Richards CA. Identification of miRNA changes in Alzheimer's disease brain and CSF yields putative biomarkers and insights into disease pathways. Journal of Alzheimers Disease. 2008a;14:27–41. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogswell JP, Ward J, Taylor IA, Waters M, Yunling S, Cannon B, Kelnar K, Kemppainen J, Brown D, Caifu C, Prinjha RK, Richardson JC, Saunders AM, Roses AD, Richards CA. Identification of miRNA changes in Alzheimer's disease brain and CSF yields putative biomarkers and insights into disease pathways. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease. 2008b;14:27–41. doi: 10.3233/jad-2008-14103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean B, Keriakous D, Scarr E, Thomas EA. Gene expression profiling in Brodmann's area 46 from subjects with schizophrenia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2007;41:308–320. doi: 10.1080/00048670701213245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood SL, Harrison PJ. Synaptic pathology in the anterior cingulate cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorders. A review and a Western blot study of synaptophysin, GAP-43 and the complexins. Brain Research Bulletin. 2001;55:569–578. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emamian ES, Hall D, Birnbaum MJ, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA. Convergent evidence for impaired AKT1-GSK3beta signaling in schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2004;36:131–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright AJ, John B, Gaul U, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. MicroRNA targets in drosophila. Genome Biology. 2004;5 doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of posttranscriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nature Reviews Genetics. 2008;9:102–114. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiore R, Siegel G, Schratt G. MicroRNA function in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta-Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2008;1779:471–478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. MiRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34:D140–D144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T, Olsen L, Lindow M, Jakobsen KD, Ullum H, Jonsson E, Andreassen OA, Djurovic S, Melle I, Agartz I, Hall H, Timm S, Wang AG, Werge T. Brain expressed microRNAs implicated in schizophrenia etiology. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison PJ, Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence. Mol Psychiatry. 2005;10:40–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M, Iwata N, Suzuki T, Kitajima T, Yamanouchi Y, Kinoshita Y, Inada T, Ozaki N. Association of AKT1 with schizophrenia confirmed in a Japanese population. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:698–700. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablensky A, Sartorius N, Ernberg G, Anker M, Korten A, Cooper JE, Day R, Bertelsen A. Schizophrenia – manifestations, incidence and course in different cultures – a world-health-organization 10-country study. Psychological Medicine. 1992:1–97. doi: 10.1017/s0264180100000904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC. Glutamate and schizophrenia: phencyclidine, N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors, and dopamine–glutamate interactions. Integrating the Neurobiology of Schizophrenia. 2007;78 doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78003-5. 69 -+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junn E, Lee KW, Jeong BS, Chan TW, Im JY, Mouradian MM. Repression of alpha-synuclein expression and toxicity by microRNA-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13052–13057. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906277106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Kuratomi G, Kato N. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Drugs Today (Barc) 2005;41:335–344. doi: 10.1358/dot.2005.41.5.893616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kefas B, Godlewski J, Comeau L, Li Y, Abounader R, Hawkinson M, Lee J, Fine H, Chiocca EA, Lawler S, Purow B. MicroRNA-7 inhibits the epidermal growth factor receptor and the Akt pathway and is down-regulated in glioblastoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3566–3572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Diehl SR. The genetics of schizophrenia — a current, genetic-epidemiologic perspective. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1993;19:261–285. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gruenberg AM, Kinney DK. Independent diagnoses of adoptees and relatives as defined by Dsm-Iii in the provincial and national samples of the Danish adoption study of schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:456–468. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950060020002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirov G, Gumus D, Chen W, Norton N, Georgieva L, Sari M, O'Donovan MC, Erdogan F, Owen MJ, Ropers HH, Ullmann R. Comparative genome hybridization suggests a role for NRXN1 and APBA2 in schizophrenia. Human Molecular Genetics. 2008;17:458–465. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Sonntag KC, Isacson O, Kosik KS. Specific microRNAs modulate embryonic stem cell-derived neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2006;24:857–864. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuss AW, Chen W. MicroRNAs in brain function and disease. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 2008;8:190–197. doi: 10.1007/s11910-008-0031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nature Genetics. 2002;30:363–364. doi: 10.1038/ng865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC. Predicting and validating microRNA targets. Genome Biol. 2004;5:115. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee O, Kim VN. Evidence that microRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. Cell Structure and Function. 2004;29:68. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y, Kim M, Han JJ, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. Embo Journal. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefever S, Hellemans J, Pattyn F, Przybylski DR, Taylor C, Geurts R, Untergasser A, Vandesompele J. RDML: structured language and reporting guidelines for real-time quantitative PCR data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(7):2065–2069. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, varez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, Sweet-Cordero A, Ebert BL, Mak RH, Ferrando AA, Downing JR, Jacks T, Horvitz HR, Golub TR. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugli G, Larson J, Martone ME, Jones Y, Smalheiser NR. Dicer and eIF2c are enriched at postsynaptic densities in adult mouse brain and are modified by neuronal activity in a calpain-dependent manner. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005;94:896–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestdagh P, Feys T, Bernard N, Guenther S, Chen C, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. High-throughput stem-loop RT-qPCR miRNA expression profiling using minute amounts of input RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(21):e143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Fiorentini C, Busi C, Collo G, Spano PF. The NMDA/D1 receptor complex as a new target in drug development. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2006;6:801–808. doi: 10.2174/156802606777057562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO, Jeffries C, Sullivan P. Expanding the ‘central dogma’: the regulatory role of nonprotein coding genes and implications for the genetic liability to schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2005;10:69–78. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins DO, Jeffries CD, Jarskog LF, Thomson JM, Woods K, Newman MA, Parker JS, Jin JP, Hammond SM. MicroRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Genome Biology. 2007;8 doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-2-r27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M, Amador XF, Girardi P, Harkavy-Friedman J, Harrow M, Kaplan K, Krausz M, Lester D, Meltzer HY, Modestin J, Montross LP, Mortensen PB, Munk-Jorgensen P, Nielsen J, Nordentoft M, Saarinen PI, Zisook S, Wilson ST, Tatarelli R. Suicide risk in schizophrenia: learning from the past to change the future. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2007;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009a;460:748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, Visscher PM, O'Donovan MC, Sullivan PF, Sklar P, Purcell Leader SM, Stone JL, Sullivan PF, Ruderfer DM, McQuillin A, Morris DW, O'Dushlaine CT, Corvin A, Holmans PA, O'Donovan MC, Sklar P, Wray NR, Macgregor S, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, O'Donovan MC, Visscher PM, Gurling H, Blackwood DH, Corvin A, Craddock NJ, Gill M, Hultman CM, Kirov GK, Lichtenstein P, McQuillin A, Muir WJ, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ, Pato CN, Purcell SM, Scolnick EM, St CD, Stone JL, Sullivan PF, Sklar LP, O'Donovan MC, Kirov GK, Craddock NJ, Holmans PA, Williams NM, Georgieva L, Nikolov I, Norton N, Williams H, Toncheva D, Milanova V, Owen MJ, Hultman CM, Lichtenstein P, Thelander EF, Sullivan P, Morris DW, O'Dushlaine CT, Kenny E, Quinn EM, Gill M, Corvin A, McQuillin A, Choudhury K, Datta S, Pimm J, Thirumalai S, Puri V, Krasucki R, Lawrence J, Quested D, Bass N, Gurling H, Crombie C, Fraser G, Leh KS, Walker N, St CD, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ, McGhee KA, Pickard B, Malloy P, Maclean AW, Van BM, Wray NR, Macgregor S, Visscher PM, Pato MT, Medeiros H, Middleton F, Carvalho C, Morley C, Fanous A, Conti D, Knowles JA, Paz FC, Macedo A, Helena AM, Pato CN, Stone JL, Ruderfer DM, Kirby AN, Ferreira MA, Daly MJ, Purcell SM, Sklar P, Purcell SM, Stone JL, Chambert K, Ruderfer DM, Kuruvilla F, Gabriel SB, Ardlie K, Moran JL, Daly MJ, Scolnick EM, Sklar P. Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Nature. 2009b;460(7256):748–752. doi: 10.1038/nature08185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogaev EI. Small RNAs in human brain development and disorders. Biochemistry—Moscow. 2005;70:1404–1407. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0276-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schratt GM, Tuebing F, Nigh EA, Kane CG, Sabatini ME, Kiebler M, Greenberg ME. A brain-specific microRNA regulates dendritic spine development. Nature. 2006;439:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nature04367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwab SG, Hoefgen B, Hanses C, Hassenbach MB, Albus M, Lerer B, Trixler M, Maier W, Wildenauer DB. Further evidence for association of variants in the AKT1 gene with schizophrenia in a sample of European sib-pair families. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:446–450. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sempere LF, Freemantle S, Pitha-Rowe I, Moss E, Dmitrovsky E, Ambros V. Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biology. 2004;5 doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Levinson DF, Duan J, Sanders AR, Zheng Y, Pe'er I, Dudbridge F, Holmans PA, Whittemore AS, Mowry BJ, Olincy A, Amin F, Cloninger CR, Silverman JM, Buccola NG, Byerley WF, Black DW, Crowe RR, Oksenberg JR, Mirel DB, Kendler KS, Freedman R, Gejman PV. Common variants on chromosome 6p22.1 are associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2009a;460(7256):753–757. doi: 10.1038/nature08192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, Nimgaonkar VL, McQueen MB, Faraone SV, Kirby A, de Bakker PI, Ogdie MN, Thase ME, Sachs GS, Todd-Brown K, Gabriel SB, Sougnez C, Gates C, Blumenstiel B, Defelice M, Ardlie KG, Franklin J, Muir WJ, McGhee KA, MacIntyre DJ, McLean A, VanBeck M, McQuillin A, Bass NJ, Robinson M, Lawrence J, Anjorin A, Curtis D, Scolnick EM, Daly MJ, Blackwood DH, Gurling HM, Purcell SM. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Rujescu D, Cichon S, Pietilainen OPH, Ingason A, Steinberg S, Fossdal R, Sigurdsson E, Sigmundsson T, Buizer-Voskamp JE, Hansen T, Jakobsen KD, Muglia P, Francks C, Matthews PM, Gylfason A, Halldorsson BV, Gudbjartsson D, Thorgeirsson TE, Sigurdsson A, Jonasdottir A, Jonasdottir A, Bjornsson A, Mattiasdottir S, Blondal T, Haraldsson M, Magnusdottir BB, Giegling I, Moller HJ, Hartmann A, Shianna KV, Ge DL, Need AC, Crombie C, Fraser G, Walker N, Lonnqvist J, Suvisaari J, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Paunio T, Toulopoulou T, Bramon E, Di Forti M, Murray R, Ruggeri M, Vassos E, Tosato S, Walshe M, Li T, Vasilescu C, Muhleisen TW, Wang AG, Ullum H, Djurovic S, Melle I, Olesen J, Kiemeney LA, Franke B, Sabatti C, Freimer NB, Gulcher JR, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Andreassen OA, Ophoff RA, Georgi A, Rietschel M, Werge T, Petursson H, Goldstein DB, Nothen MM, Peltonen L, Collier DA, St Clair D, Stefansson K. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455(7210):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature07229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefansson H, Ophoff RA, Steinberg S, Andreassen OA, Cichon S, Rujescu D, Werge T, Pietilainen OP, Mors O, Mortensen PB, Sigurdsson E, Gustafsson O, Nyegaard M, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Ingason A, Hansen T, Suvisaari J, Lonnqvist J, Paunio T, Borglum AD, Hartmann A, Fink-Jensen A, Nordentoft M, Hougaard D, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Bottcher Y, Olesen J, Breuer R, Moller HJ, Giegling I, Rasmussen HB, Timm S, Mattheisen M, Bitter I, Rethelyi JM, Magnusdottir BB, Sigmundsson T, Olason P, Masson G, Gulcher JR, Haraldsson M, Fossdal R, Thorgeirsson TE, Thorsteinsdottir U, Ruggeri M, Tosato S, Franke B, Strengman E, Kiemeney LA, Group Melle I, Djurovic S, Abramova L, Kaleda V, Sanjuan J, de FR, Bramon E, Vassos E, Fraser G, Ettinger U, Picchioni M, Walker N, Toulopoulou T, Need AC, Ge D, Lim YJ, Shianna KV, Freimer NB, Cantor RM, Murray R, Kong A, Golimbet V, Carracedo A, Arango C, Costas J, Jonsson EG, Terenius L, Agartz I, Petursson H, Nothen MM, Rietschel M, Matthews PM, Muglia P, Peltonen L, St CD, Goldstein DB, Stefansson K, Collier DA, Kahn RS, Linszen DH, van OJ, Wiersma D, Bruggeman R, Cahn W, de HL, Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I. Common variants conferring risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2009a;460(7256):744–747. doi: 10.1038/nature08186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JM, Morrison PD, Pilowsky LS. Glutamate and dopamine dysregulation in schizophrenia — a synthesis and selective review. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:440–452. doi: 10.1177/0269881106073126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone JL, O'Donovan MC, Gurling H, Kirov GK, Blackwood DHR, Corvin A, Craddock NJ, Gill M, Hultman CM, Lichtenstein P, McQuillin A, Pato CN, Ruderfer DM, Owen MJ, St Clair D, Sullivan PF, Sklar P, Purcell SM. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia. Nature. 2008;455:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature07239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg R, Castensson A, Jazin E. Statistical modeling in case-control real-time RT-PCR assays, for identification of differentially expressed genes in schizophrenia. Biostatistics. 2006;7:130–144. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxi045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang FC, Hajkova P, Barton SC, Lao KQ, Surani MA. MicroRNA expression profiling of single whole embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Research. 2006;34 doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiselton DL, Vladimirov VI, Kuo PH, McClay J, Wormley B, Fanous A, O'Neill FA, Walsh D, Van den Oord EJCG, Kendler KS, Riley BP. AKT1 is associated with schizophrenia across multiple symptom dimensions in the Irish study of high density schizophrenia families. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;63:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, Webster M, Knable M, Johnston N, Yolken RH. The Stanley Foundation brain collection and neuropathology consortium. Schizophrenia Research. 2000;44:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(99)00192-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyota T, Yamada K, tera-Wadleigh SD, Yoshikawa T. Analysis of a cluster of polymorphisms in AKT1 gene in bipolar pedigrees: a family-based association study. Neuroscience Letters. 2003;339:5–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01428-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Sanchez MA, Liu JD, Hannon GJ, Parker R. Control of translation and mRNA degradation by miRNAs and siRNAs. Genes & Development. 2006;20:515–524. doi: 10.1101/gad.1399806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vawter MP, Thatcher L, Usen N, Hyde TM, Kleinman JE, Freed WJ. Reduction of synapsin in the hippocampus of patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:571–578. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vo N, Klein ME, Varlamova O, Keller DM, Yamamoto T, Goodman RH, Impey S. A cAMP-response element binding protein-induced microRNA regulates neuronal morphogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:16426–16431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508448102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Wang X. Systematic identification of microRNA functions by combining target prediction and expression profiling. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1646–1652. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weickert CS, Hyde TM, Lipska BK, Herman MM, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor in prefrontal cortex of patients with schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2003;8:592–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B, Roos JL, Levy S, Van Rensburg EJ, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nature Genetics. 2008;40:880–885. doi: 10.1038/ng.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zammit S, Allebeck P, Dalman C, Lundberg I, Hemmingsson T, Lewis G. Investigating the association between cigarette smoking and schizophrenia in a cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:2216–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.12.2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Huang J, Yang N, Greshock J, Megraw MS, Giannakakis A, Liang S, Naylor TL, Barchetti A, Ward MR, Yao G, Medina A, O'brien-Jenkins A, Katsaros D, Hatzigeorgiou A, Gimotty PA, Weber BL, Coukos G. MicroRNAs exhibit high frequency genomic alterations in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9136–9141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508889103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.