Given the stage in life in which inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is typically diagnosed, its effect on quality of life and career path, among others, can be particularly distressing to individuals with the condition and their family members. Research investigating the impact of IBD on the quality of life and health literacy of Canadian patients has been scarce. Accordingly, this mixed-methods survey study examined factors that IBD patients consider to be important in improving quality of life.

Keywords: Crohn disease, Health literacy, Impact, Inflammatory bowel disease, Knowledge translation, Ulcerative colitis

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Despite improvements in therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), patient quality of life continues to be significantly impacted.

OBJECTIVE:

To assess the impact of IBD on patients and families with regard to leisure, relationships, mental well-being and financial security, and to evaluate the quality and availability of IBD information.

METHODS:

An online survey was advertised on the Crohn’s and Colitis Canada website, and at gastroenterology clinics at the University of Alberta Hospital (Edmonton, Alberta) and University of Calgary Hospital (Calgary, Alberta).

RESULTS:

The survey was completed by 281 IBD patients and 32 family members. Among respondents with IBD, 64% reported a significant or major impact on leisure activities, 52% a significant or major impact on interpersonal relationships, 40% a significant or major impact on financial security, and 28% a significant or major impact on planning to start a family. Patient information needs emphasized understanding disease progression (84%) and extraintestinal symptoms (82%). There was a strong interest in support systems such as health care insurance (70%) and alternative therapies (66%). The most common source of information for patients was their gastroenterologist (70%); however, most (70%) patients preferred to obtain their information from the Crohn’s and Colitis Canada website.

CONCLUSIONS:

The impact of IBD on interpersonal relationships and leisure activities was significant among IBD patients and their families. Understanding the disease, but also alternative treatment options, was of high interest. Currently, there is a discrepancy between interest in information topics and their availability. Respondents reported a strong desire to obtain information regarding disease progression, especially extraintestinal symptoms.

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Malgré les améliorations aux traitements des maladies inflammatoires de l’intestin (MII), la qualité de vie des patients continue d’être considérablement touchée.

OBJECTIF :

Évaluer les effets des MII sur les patients et leur famille en ce qui a trait aux loisirs, aux relations, au bien-être mental et à la sécurité financière, ainsi que la qualité et l’accessibilité de l’information sur les MII.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Un sondage virtuel a été annoncé dans le site Web de Crohn et Colite Canada ainsi qu’aux cliniques de gastroentérologie de l’University of Alberta Hospital d’Edmonton et de l’University of Calgary Hospital, en Alberta.

RÉSULTATS :

Dans l’ensemble, 281 patients atteints d’une MII et 32 membres de leur famille ont rempli le sondage. Les répondants atteints d’une MII ont déclaré un effet significatif ou majeur sur leurs loisirs (64 %), leurs relations interpersonnelles (52 %), leur sécurité financière (40 %) et leur planification pour fonder une famille (28 %). Ils voulaient plus d’information sur l’évolution de la maladie (84 %) et les symptômes extra-intestinaux (82 %). Ils manifestaient beaucoup d’intérêt envers les systèmes de soutien comme l’assurance médicale (70 %) et les traitements parallèles (66 %). Le gastroentérologue (70 %) était leur principale source d’information, mais la plupart (70 %) préféraient obtenir l’information dans le site Web de Crohn et Colite Canada.

CONCLUSIONS :

Les MII ont des effets significatifs sur les relations interpersonnelles et les loisirs des patients atteints d’une MII et de leur famille. Les répondants manifestaient beaucoup d’intérêt à comprendre leur maladie, mais également les possibilités de traitements parallèles. Ils constataient un écart entre leur intérêt envers les sujets d’information et leur accessibilité. Ils se disaient très désireux d’obtenir de l’information sur l’évolution de la maladie, notamment les symptômes extra-intestinaux.

The prevalence and incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) in Canada are among the highest world (1–3). Despite the improvement in therapeutic options and disease management, IBD continues to have a negative impact on the quality of life (QoL) of patients (2,4,5). This is mainly due to the symptoms of IBD during the active stage of the disease, which may include diarrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss and fatigue. However, even during periods of clinical remission, patients experience psychological distress, which impacts their QoL (6,7).

In a European study (8), 56% of IBD respondents reported that IBD had impacted their career path, and that 31% had to quit or lost their job due to IBD. Furthermore, their private life was considerably impacted – 35% of respondents indicated that living with IBD kept them from pursuing intimate relationships. However, IBD patients have reported that participation in patient organizations positively impacted their QoL. The same survey demonstrated that IBD patients request that management practices for IBD should also address struggles with everyday life, coping with symptoms in remission, such as fatigue, and raising awareness among the general population (8). European patients with IBD did not believe that their doctor was interested in the effect of IBD on their QoL (4). However, there has been a paucity of research assessing the impact of IBD on QoL in Canadian patients, or opportunities to assess the health literacy needs of persons living with IBD.

IBD is most often diagnosed in the third decade of life or earlier (9), when individuals are focusing on their personal growth, education, relationships and independence. Being affected with a chronic condition, such as IBD, especially in this critical phase of life, is emotionally challenging (10). Similarly, family members of patients play a significant role in the lives of IBD patients. Given that IBD primarily affects emerging adults, but also affects children, it highlights the importance of involving family members in the present survey.

The objective of the present study was to assess the impact of living with IBD or living with a family member suffering from IBD with regard to personal life, mental well-being, education, career choices and financial security. Furthermore, we aimed to obtain a better understanding of what information patients and their family members would like to have access to in empowering them in disease and life management, and how they perceive the availability and quality of current information, recognizing that the ultimate goal of patient care is to improve QoL.

METHODS

Recruitment

A mixed-methods (quantitative/qualitative) survey was developed through conversations with two focus groups consisting of doctors from the Alberta Inflammatory Bowel Disease Consortium, representatives from Crohn’s and Colitis Canada (CCC), patients living with IBD and their family members. The survey was hosted on SurveyMonkey (USA) from February 2013 until February 2014, and recruitment of participants occurred via the CCC website and through pamphlets in the gastroenterology outpatient clinics at the University of Alberta Hospital (Edmonton, Alberta) and University of Calgary (Calgary, Alberta). Individuals were informed about the nature of the study and provided digital informed consent. All responses were collected anonymously.

Questionnaire

The survey was structured in three parts: demographic information including details regarding their disease; the impact of IBD on their lives; and health literacy/information needs. The content of the survey was developed by a knowledge translation advisory committee consisting of youth and adult patients with IBD, family members of patients, representatives of the CCC, a knowledge translation specialist, and an adult and a pediatric gastroenterologist. The complete questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1. In the latter part of the survey, IBD patients were asked to indicate which type of information they would like to have access to, and how they rate the availability and quality of current information. A total of 16 options in four major categories were provided. The first category was information regarding the primary clinical aspects of IBD, such as understanding disease progression, differentiating symptom remission from clinical remission, and the risks and side effects of pharmaceuticals. The second category was information regarding secondary clinical aspects of IBD such as extraintestinal symptoms, mental health and sexual health. The third category was about diet, exercise, alternative therapies and mental well-being; the fourth category focused on health care and work-life-related topics.

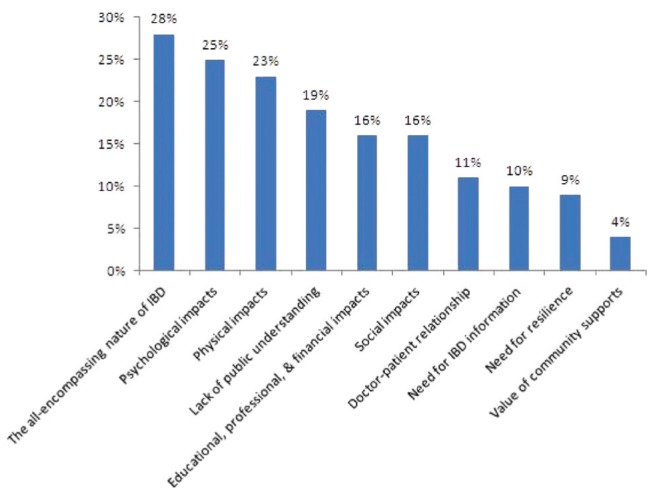

Open-ended questions were also included to provide respondents the opportunity express the impacts of IBD that were not specifically asked in the quantitative questions. A total of 159 respondents took the opportunity to provide this additional information. The responses were reviewed for content and categorized into 10 common themes. Each individual response was given a thematic tag corresponding to these themes and could receive multiple tags. Because each of the 159 individual responses could be tagged for multiple themes, 255 thematic responses were recorded.

Included in the survey were all respondents who provided digital informed consent for their anonymous information to be included in the data analysis and publically reported, and who completed the survey. Individuals who only completed the demographic information before exiting the survey were excluded because they did not respond to the key survey questions regarding impact of living with IBD. The study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corporation, USA); P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Differences in age between ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn disease (CD) respondents was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t test. Differences in sex between UC and CD respondents were assessed using a χ2 test on contingency tables.

RESULTS

Respondent demographics

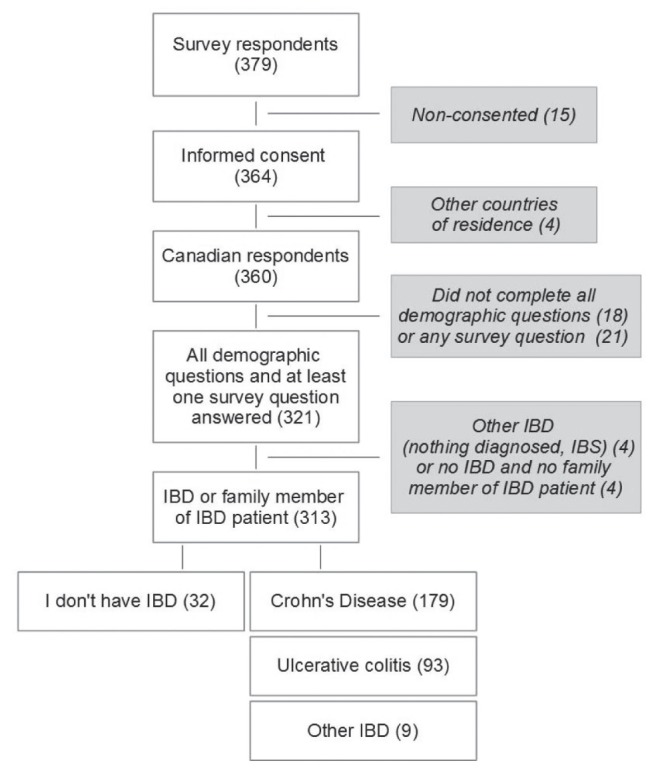

A total of 313 respondents were included in the analysis: 281 were affected with IBD and 32 were family members of IBD patients (Figure 1). Of the individuals with IBD, 62% had CD, 32% had UC and 6% were IBD unclassified. The majority (77%) of respondents were female, and 99% of respondents were from Canada, including Ontario (43%), Alberta (25%), Atlantic provinces (11%) and British Columbia (10%). Most respondents resided in urban settings (73%).

Figure 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. Respondents who did not give their digital consent, who lived in countries other than Canada or who skipped the survey questions were excluded. The included study population consisted of 313 individuals, of whom 32 are family members of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients, and 281 are affected with Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis or IBD unclassified. IBS Irritable bowel syndrome

CD patients were younger at onset and diagnosis than UC patients (Table 1). Individuals with UC experienced a shorter interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis. The age distribution at IBD diagnosis was different in the subgroups of CD and UC, with a larger proportion of UC respondents being diagnosed while being between 20 and 29 years of age compared with CD (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Age and sex distribution of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) respondents

| Crohn disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Total respondents* | 179 (65) | 93 (34) |

| Male | 41 (23) | 24 (26) |

| Female | 138 (77) | 69 (74) |

| Age at onset, years | ||

| 0–19 | 14 (8) | 3 (3) |

| 20–29 | 38 (21) | 32 (34)† |

| 30–39 | 56 (31) | 23 (25) |

| 40–49 | 37 (21) | 18 (19) |

| 50–59 | 27 (15) | 14 (15) |

| 60–69 | 7 (4) | 3 (3) |

| Age at onset, years, mean (95% CI) | 20.6 (19.0–22.2) | 26.6 (24.3–29.0)† |

| Age at diagnosis, years, mean (95% CI) | 26.5 (24.8–28.1) | 29.4 (27.0–31.9)† |

| Interval, diagnosis–onset, years, mean (95% CI) | 5.9 (4.8–6.9) | 2.9 (2.0–3.7)‡ |

Data presented as n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Individuals with IBD unclassified were not included in this analysis. Different from Crohn disease at

P<0.05;

P<0.001

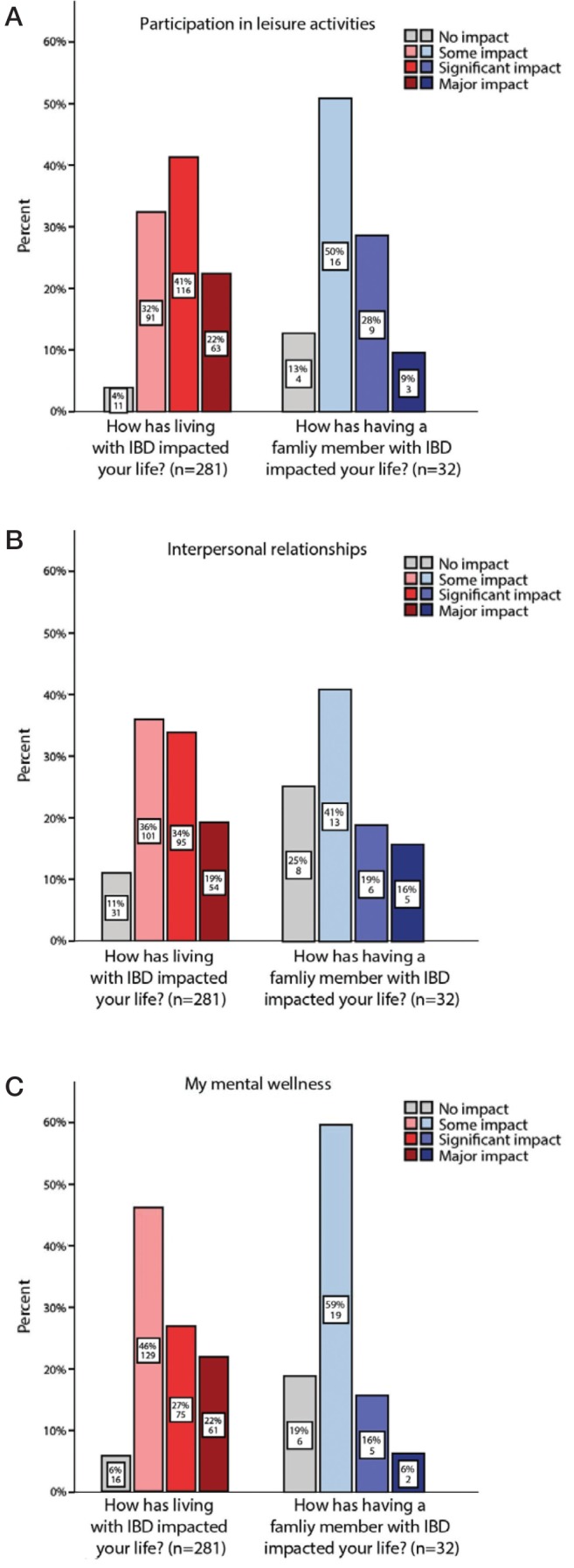

Impact of IBD

In the majority of aspects, >70% of respondents indicated that IBD or living with a family member who has IBD impacted their lives. The most impacted aspects were participation in leisure activities, interpersonal relationships with friends, family and intimate partners, and mental well-being (Figure 2; Table 2).

Figure 2).

Three most relevant topics (A, B, C) of the impact of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) on the lives of IBD patients and family members were assessed (no impact to major impact)

TABLE 2.

Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on 179 Crohn disease (CD) and 93 ulcerative colitis (UC) patients

| No impact | Some impact | Significant impact | Major impact | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| CD | UC | CD | UC | CD | UC | CD | UC | |

| Participation in leisure activities | 9 (5) | 2 (2) | 60 (34) | 30 (32) | 68 (38) | 43 (46) | 45 (20) | 18 (19) |

| Interpersonal relationships | 19 (11) | 12 (13) | 64 (36) | 35 (38) | 54 (30) | 35 (38) | 42 (24) | 11 (12)* |

| Mental well-being | 9 (5) | 7 (8) | 80 (45) | 44 (47) | 46 (26) | 26 (28) | 44 (25) | 16 (17) |

| Obtaining advanced education | 54 (30) | 30 (32) | 74 (41) | 35 (38) | 31 (17) | 15 (16) | 20 (11) | 13 (14) |

| Pursuing the career of my choice | 44 (25) | 19 (20) | 58 (32) | 37 (40) | 42 (24) | 20 (22) | 35 (20) | 17 (18) |

| Financial burden | 34 (19) | 16 (17) | 74 (41) | 40 (43) | 32 (18) | 23 (25) | 39 (22) | 14 (15) |

| Plans to have children | 82 (46) | 51 (55) | 43 (24) | 18 (19) | 25 (14) | 13 (14) | 29 (16) | 11 (12) |

Data presented as n (%).

Different from Crohn disease at P<0.05

Other aspects, such as education, career pursuits, family planning and the financial burden of IBD, had a significant, but lower impact on respondents’ lives (Table 2). Impact ratings were similar when comparing respondents diagnosed with CD and UC except for the impact of IBD on interpersonal relationships, which was rated as majorly impacted by 24% and 12% of CD and UC respondents, respectively. Among the latter categories, pursuing the career of their choice and financial burden were considered to be somewhat, significantly or majorly impacted by IBD in 78% and 82% of CD and UC patients, respectively.

The most common open-ended response (28% of respondents) was that IBD is all-encompassing – that is, it impacts all aspects of life including physical, social, financial and others. The next most common responses were to comment on the psychological impact of living with IBD (25%), the physical impact of living with IBD (23%) and the difficulties raised by a lack of public understanding of the disease (19%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3).

Knowledge translation topics relevant to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Answers to open-ended questions were assigned to 10 topics and responses were counted. A combination of multiple topics in one answer was possible (n=159)

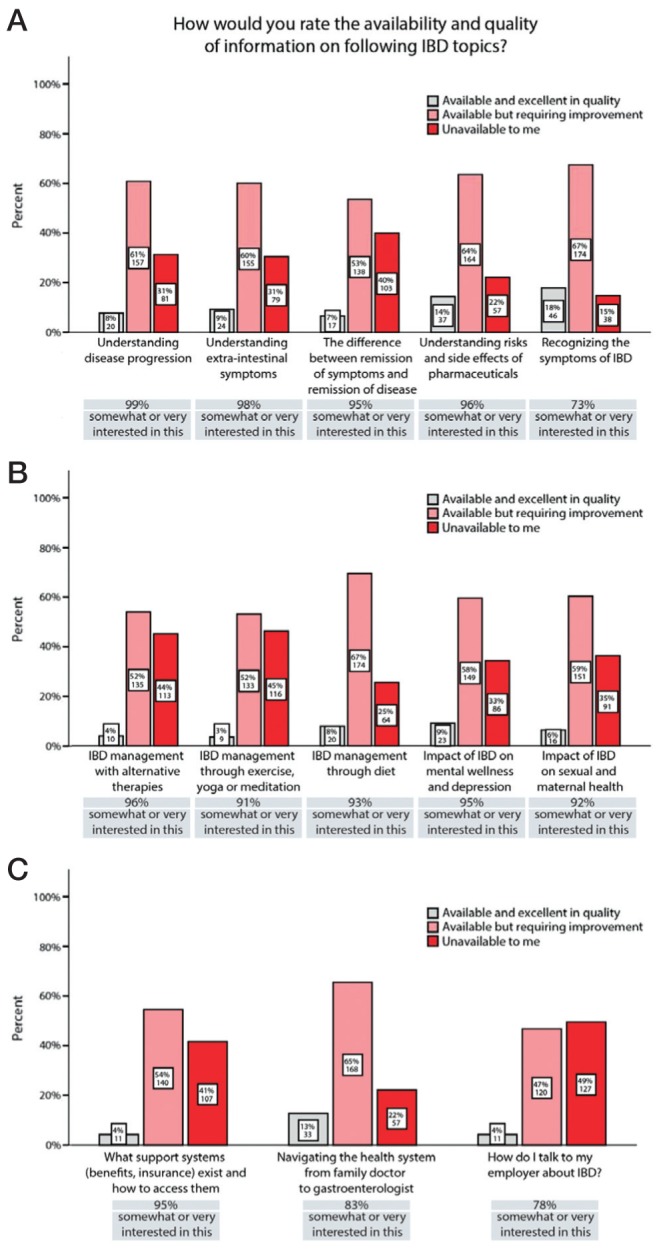

Information needs and quality – IBD patients

Knowing more about disease progression and what to expect in the years ahead was rated to be very interesting by 84%, and somewhat interesting by 15% of respondents (Figure 4A). A similar picture was observed for information regarding extraintestinal symptoms (82% very interested; however, 31% reported difficulty in finding that information) and recognizing the difference between remission of symptoms and remission of disease (75% very interested; however, 40% reported difficulty finding that information).

Figure 4).

Quality and availability of information and level of interest in 281 Canadian inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients. Quality and availability of information on medical (A), management of IBD (B) and health care-related topics (C) was assessed, in addition to the level of interest in these topics. Percentages of responses ‘somewhat interested’ and ‘very interested’ were cumulated to provide an overall picture of the level of interest

Respondents reported a strong interest in information regarding the impact of IBD on mental well-being (66% very interested), the management of IBD with nonconventional therapies such as alternative medicine (66% very interested; however, 44% reported difficulty in finding that information), yoga and meditation (53% very interested; however, 45% reported difficulty in finding that information), and dietary management of symptoms (66% very interested; however, 25% reported difficulty in finding that information) (Figure 4B).

Information needs concerning health care and support systems and employment were variable, with the most sought after information being about support systems (ie, benefits, insurance coverage), which was rated to be very interesting by 70% of respondents (Figure 4C).

Respondents also had the opportunity to provide open-ended comments regarding their information needs. Of 61 responses, 38 repeated subjects that were available in the multiple-choice format. Of the 23 original responses, the most common original response was the request for up-to-date information regarding the latest research in IBD causes and treatments (19 respondents). Representative comments included:

Access to the most up to date research and medical understanding of how Crohn’s disease works; and

How is the microbiome involved, and how can [IBD] be treated though manipulating [the microbiome] instead of immune suppression.

Sources of information

The majority of respondents indicated that they obtain their information from their gastroenterologist (72% CD, 73% UC) (Table 3). The Internet was reported to be a major source of information, with 56% (CD) and 58% (UC) reporting using the Internet in general for IBD information, and 54% (CD) and 57% (UC) specifically relying on the CCC website. More than one-third stated that they also seek information from other patients with IBD (38% CD, 37% UC).

TABLE 3.

Current and desired sources of information for inflammatory bowel disease patients

| Crohn disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Current sources of information | ||

| Gastroenterologist | 128 (67) | 68 (69) |

| Other online sources | 101 (53) | 54 (55) |

| Crohn’s and Colitis Canada website | 97 (51) | 53 (54) |

| Other people with | 68 (36) | 34 (34) |

| Family doctor | 39 (21) | 28 (28) |

| Crohn’s and Colitis Canada-sponsored events | 23 (12) | 10 (10) |

| Other health care professionals | 29 (11) | 12 (12) |

| Preferred sources of information | ||

| Crohn’s and Colitis Canada website | 122 (64) | 72 (73) |

| Information mailed to me | 97 (51) | 40 (40) |

| Pamphlets at my doctor’s office | 63 (33) | 45 (45) |

| Smartphone applications | 66 (35) | 32 (32) |

Data presented as n (%)

When asked how individuals would like access to further information on IBD, the majority would prefer the CCC website (68% CD, 77% UC) and information being mailed to their homes (54% CD, 43% UC) (Table 3).

Eighty-one open-ended responses were collected, of which 63 were coded to larger themes that emerged from the survey. The most common response (n=28) was to emphasize the need for more information on IBD, and the role that doctors need to play in sharing that information with patients. A related theme was the need to better educate the general public about IBD (n=7) and the frustration of having an uneducated public being unsympathetic to the challenges of living with IBD. Another theme was to comment on the importance of IBD support services (n=8), and the need for additional services in rural areas or specific municipalities. The services provided by the CCC were generally commended (n=6), although some suggestions to improve services were made.

DISCUSSION

The present survey evaluated the impact of IBD on career development, family planning and psychological factors. We also included open-ended questions to offer participants a chance to comment on their struggles. The final part of the questionnaire was designed to assess the current perception of the quality of information available to patients and families. This will enable support organizations (ie, CCC) and physicians to improve current information regarding management, nutrition and other aspects of living with IBD. The CCC and the Alberta IBD Consortium have worked consistently toward providing a reliable source of information for IBD patients in Canada and internationally. Comprised of an expert committee that regularly updates and adapts guidelines according to the latest research, the CCC is constantly trying to improve QoL for patients. In this endeavour, the current survey was designed to shed light on the more personal aspects and struggles of patients.

In the survey, the mean age of diagnosis was 26.5 years (CD) and 29.4 years (UC). The mean age of diagnosis coincides with the age group considered to be the most computer literate.

In a Canadian study analyzing the accessibility and usage of Internet (11), young adults had the highest reported percentage of having “ever used Internet”. With respect to electronic health literacy, also termed eHealth literacy, age and socioeconomic factors play an important role, with younger respondents and individuals with higher socioeconomic status showing better eHealth literacy (12).

The selection of respondents was biased by the fact that the survey was advertised on the CCC website, and that it was only available as an online survey. Furthermore, we only targeted tertiary IBD clinics in Calgary and Edmonton. Patients and family members who browse for IBD-related information or specifically seek information on the CCC website are more likely to experience a higher impact of IBD on their lives compared with patients who are coping well. However, this limitation was considered to be justified in the study design because a major objective was to inform the future delivery of IBD information to persons who are actively engaging with patient organizations and seeking information online. The willingness to complete a survey can also be suspected to be higher in patients who struggle with IBD. Also, the online survey likely excluded less computer-literate individuals and individuals without Internet access at home. This may have resulted in a slight under-representation of the elderly and rural populations. A Canadian study investigating Internet access from different perspectives (11) reported that 80% of urban versus 70% of rural citizens have ever used the Internet.

Regarding QoL, IBD patients generally score lower on this metric compared with the general population (13). Parents of children suffering from IBD also report a lower QoL score compared with parents of healthy children (14). From what we found with our Canadian survey, the impairment of social activities and interactions is one important aspect that contributes to low QoL scores. Participation in leisure activities, interpersonal relationships and mental well-being were considered by IBD patients and their family members to be most impacted by the disease. These findings are similar to a German study that found the general life satisfaction of IBD patients was most compromised in aspects of health, leisure time and interpersonal relationships (15). When combining ‘major’ and ‘significant’ impact, the impact of IBD with regard to interpersonal relationships was similar in UC and CD patients, which is in contrast to the German study, which showed a higher perceived burden in UC patients (15). However, the tendency that CD patients appear to rate the impact of IBD on their lives higher than UC patients is supported by the findings that some CD patients may experience more pronounced psychological morbidity (16). In contrast to leisure and relationships, family planning, career decisions and finances were reported by IBD patients and family members as having a significant but lower impact, which is similar to the findings reported by Janke et al (15). This information is especially important for family doctors, gastroenterologists and patient organizations because it enables them to incorporate these topics into their advice to patients.

One concern that respondents voiced in the open-ended section was travel to unknown locations and the anxiety associated with finding a washroom. Several smartphone applications (eg, ‘SitOrSquat’, ‘Toilet Finder’, ‘Where to Wee’ and ‘Bathroom Scout’) that allow users to find washrooms in the area are available, and are tools that would be very helpful when going to unknown locations, especially rural areas within Canada. Additionally, the CCC ‘GoHere’ decal program is recruiting businesses, making a washroom available for emergencies and has an app available for download (since December 2014). These tools are based on the submissions of users; clearly, the promotion and knowledge of the existence of these websites are very important. To address the significant impact of IBD on relationships with friends and sexual partners, raising public awareness may increase the chance of patients being able to speak openly about the disease and to be met with more understanding.

The categories that respondents were most interested in included medical and well-being topics. The disease progression and the uncertainty on what to expect in the years ahead was rated to be very interesting by 83% of respondents. This is a particularly difficult question to answer because the efficacy of drugs has such high variability and may change in an individual over time. Although surgery rates have decreased (17–19) and the need for surgery can be delayed in individuals by improved therapy with biologicals (20), the course of the disease over the years remains highly unpredictable. The evolving concept of tailored, ‘personalized’ management of IBD and treating the disease to an objective target are high in the priority of information needs of patients, and clinicians are beginning to realize that the personalized treatment approach can lead to higher remission rates and shorter initial disease duration (21). However, information regarding these very complex relationships and recent developments are yet to be made available to IBD patients.

Other very important areas of interest were mental well-being, alternative therapies and dietary management. These topics reflect the need of patients to better understand the management of their disease and to be presented with alternatives for, or ways to augment, standard therapy. This need may arise from several circumstances such as the lack of efficacy under standard therapy, the costs associated with therapy or the experience of side effects. It has also been reported that patients are more likely to turn to alternative medicine when they experienced longer disease duration and when they were feeling out of control (22). Patients who are interested in a holistic approach to the management of IBD that takes alternative medicine, exercise, diet and mental health into consideration should be offered reliable information from their doctors, which can help them to make an educated decision. According to a Canadian survey (23), 70% of patients indicated that they have talked to their physician about complementary and alternative medicine. On the other hand, 65% of gastroenterologists state that they do not have formal training in complementary and alternative medicine and 55% do not have a systematic approach to discussing these topics (24). Interestingly, alternative medicine and exercise were topics that also scored among the lowest in quality and availability of information; the information need, therefore, appears not to be met appropriately.

Generally, the quality and availability of information was only rated excellent by a minority of respondents, and approximately one-half indicated that improvements are required. How to communicate with employers and schools regarding IBD appears to be an under-represented topic according to the respondents, in which 48% and 53%, respectively, mentioned that this type of information is unavailable to them. The communication with employers and schools is important to patients because of the stigma associated with IBD. In a recent European study (25), 60% of IBD patients felt stressed about taking sick leave from work due to IBD, and 24% have experienced unfair comments about their performance at work from colleagues or superiors. This additional burden could be mitigated by open communication and increased awareness, helping the general population and employers better understand the impact of IBD on their colleagues and employees.

One observation made was that the perceived availability and quality of information as stated by respondents did not always correlate with the amount of information found, for example, on the CCC web-site. Some topics, such as information on drugs, sexual health and nutrition, are covered in brochures available online or by mail, but this did not appear to fully satisfy the surveyed population. Taking this into consideration, the currently available information may need to be revisited and updated to match the needs of patients, focusing on the quality and clarity of information. This is especially true given that our respondents were individuals who were active in seeking information on IBD and, thus, may have a higher health literacy than patients who do not interact with organizations such as CCC. On a similar note, we found that topics that were rated high on the priority of information needs tended to score low on quality and availability; in other words, the information sought most was perceived to be not available or of unsatisfactory quality.

Regarding the sources that individuals seek for information on IBD, it becomes clear that the gastroenterologist and online sources are most often sought, and most respondents chose at least two sources of information from the given options. These findings are similar to those reported in a survey of IBD patients with longstanding disease (26), in which respondents favoured medical specialists (ie, gastroenterologists) as the primary source of information. The fact that the gastroenterologist is consulted by the majority of CD and UC patients (67% and 69%, respectively) is a favourable outcome and emphasizes the important role of specialized physicians to provide information. Other online sources are also popular among all subgroups of individuals. The CCC website is ranked third among the information sources and, interestingly, is also consulted by many non-IBD individuals (54%). Other people with IBD appear to be a valuable source of information for at least one-third of the respondents, and this exchange of information may be of most value for the mental well-being of many patients. This result should encourage the ongoing efforts of patient organizations to host events in which patients with IBD and their families can meet one another.

Several limitations should be considered. The survey was conducted in English and, thus, our findings under-represent IBD patients living in Quebec. The participants of the survey were mostly women (78%). The sex gap in participation in online surveys is an effect that was observed in surveys of IBD patients (27) but also other health-related topics (28), which may be explained by more pronounced information-seeking behaviour in women (29) and willingness to talk about health issues (30). The responses were largely descriptive in nature and did not control for potential confounders (eg, socioeconomic status).

In the information age, the Internet provides an overwhelming amount of information, but this can also cause confusion in patients as to what information is reliable. Having access to discussion forums supported by professional organizations around the world and exchanging experiences may help the patient feel more supported in some ways. On the other hand, however, may also leave the patient with more insecurity regarding their disease management.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the respondents for participating in this survey, and Crohn’s and Colitis Canada for making the survey available.

APPENDIX 1. Questionnaire used in the present study

| 1. Demographics | |

|

| |

| Which country, province, or territory do you reside in? | United States |

| Atlantic provinces of Canada | |

| Quebec | |

| Ontario | |

| Manitoba | |

| Saskatchewan | |

| Alberta | |

| British Columbia | |

| Northwest Territories, Yukon or Nunavut | |

| Other (not in Canada or United States) | |

|

| |

| Do you live in a rural or an urban community? | Urban (within a city) |

| Rural (a small community in the country) | |

|

| |

| What is the approximate population of the community where you live? | Less than 10,000 |

| Between 10,000 and 99,999 | |

| Between 100,000 and 1,000,000 | |

| Greater than 1,000,000 | |

|

| |

| What is your gender? | Female |

| Male | |

| Transgender | |

|

| |

| What is your current age? | 0–19 |

| 20–29 | |

| 30–39 | |

| 40–49 | |

| 50–59 | |

| 60–69 | |

| 70–79 | |

| 80–89 | |

| 90–99 | |

| 100 or greater | |

|

| |

| Which of the following have you been diagnosed with? | I do not have inflammatory bowel disease |

| Crohn’s disease | |

| Ulcerative colitis | |

| Other inflammatory bowel disease | |

|

| |

| How old were you when you first experienced symptoms related to IBD? (open ended) | |

|

| |

| How old were you when you were formally diagnosed with IBD? (open ended) | |

|

| |

| 2. Quality of life – living with IBD | |

|

| |

| Please tell us about how living with IBD has impacted your life (score 0–3) | Obtaining advanced education or professional training |

| Pursuing the career of my choice | |

| Participation in leisure activities | |

| Interpersonal relationships with friends, family, and romantic partners | |

| My plans to have children | |

| My mental well-being (e.g. depression) | |

| Financial burden through expenses or lost income | |

|

| |

| What else can you tell us about living with IBD? (open ended) | |

|

| |

| Do you have one or more family members who are living with inflammatory bowel disease? | Yes |

| No | |

|

| |

| Please choose all that apply to you | I have one or more children diagnosed with Crohn’s disease |

| I have one or more children diagnosed with ulcerative colitis | |

| My spouse has been diagnosed with Crohn’s disease | |

| My spouse has been diagnosed with ulcerative colitis | |

| Other: Please Explain | |

|

| |

| Please tell us how having a family member with IBD has impacted your life (score 0–3) | Obtaining advanced education or professional training |

| Pursuing the career of my choice | |

| Participation in leisure activities | |

| Interpersonal relationships with friends and family | |

| My mental well-being (e.g. depression) | |

| Financial burden through expenses or lost income | |

|

| |

| What else can you tell us about the impact upon your life? (open ended) | |

|

| |

| 3. What information about IBD are you seeking? | |

|

| |

| What information about IBD would you like access to? (score 0–3) | Recognizing the symptoms of IBD for early detection and treatment |

| Navigating the health system from family doctor to gastroenterologist to diagnosis and treatment | |

| Understanding disease progression: What to expect in the years ahead | |

| Understanding IBD outside of the intestine – headaches, joint pains etc. | |

| The impact of IBD on mental well-being and depression | |

| The impact of IBD on sexual and maternal health | |

| The impact of IBD on childhood growth and development | |

| The difference between remission of symptoms and remission of disease | |

| Understanding risks and side-effects of pharmaceuticals | |

|

| |

| What information about IBD disease and life management would you like access to? (score 0–2) | What are the alternative (non-conventional) therapies available for IBD, and how can they support my treatment? Can IBD be managed through exercise, yoga, or meditation? |

| How can I best manage IBD through diet? | |

| What are the existing support services (eg, disability benefits, insurance coverage) and how do I access them? | |

| How do I talk to my employer about IBD? | |

| How do I talk to my child’s school about IBD? | |

| How do I support my child in transition from paediatric to adult care? | |

|

| |

| What other information would you like relating to IBD? (open ended) | |

|

| |

| 4. Communications | |

|

| |

| How would you rate the availability and quality of information on the following IBD topics? (score 0–2) | Recognizing the symptoms of IBD for early detection and treatment |

| Navigating the health system from family doctor to gastroenterologist to diagnosis and treatment | |

| Understanding disease progression: What to expect in the years ahead | |

| Understanding IBD outside of the intestine – headaches, joint pains etc. | |

| The impact of IBD on mental well-being and depression | |

| The impact of IBD on sexual and maternal health | |

| The impact of IBD on childhood growth and development | |

| The difference between remission of symptoms and remission of disease | |

| Understanding risks and side-effects of pharmaceuticals | |

|

| |

| How would you rate the availability and quality of information on the following IBD disease and life management topics? (score 0–2) | What are the alternative (non-conventional) therapies available for IBD, and how can they support my treatment? Can IBD be managed through exercise, yoga, or meditation? How can I best manage IBD through diet? |

| What are the existing support services (e.g. disability benefits, insurance coverage) and how do I access them? How do I talk to my employer about IBD? | |

| How do I talk to my child’s school about IBD? | |

| How do I support my child in transition from paediatric to adult care? | |

|

| |

| Where do you currently receive information about IBD? | From my gastroenterologist |

| From my family doctor | |

| From another healthcare professional (nurse, dietician etc.) | |

| From other people diagnosed with IBD | |

| From the CCFC website | |

| At CCFC sponsored events | |

| From other online sources | |

| Other: Please Explain | |

|

| |

| How would you like to receive information about IBD? | Pamphlets at my doctor’s office |

| Information mailed to my home | |

| Through the CCFC website | |

| Through Smart Phone Applications | |

| Other: Please Explain | |

|

| |

| 5. Other | |

|

| |

| In conclusion, is there anything else you would like to tell us (open ended) | |

Footnotes

FUNDING: This project was funded by the Alberta Inflammatory Bowel Disease Consortium, which is funded by an AHFMR Interdisciplinary Team Grant. AHFMR is now Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions.

CONTRIBUTIONS: Study concept and design: DG, HWB, SG, LAD, RP, EW, RNF and GGK. Data acquisition: DG and HWB. Analysis and interpretation of the data: HMB, HWB, SG, DG, LAD, EW, AF, RNF, SG and GGK. Statistical analysis: HMB. Drafting of the manuscript: HMB, HWB, DG and SG. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: HMB, HWB, DG, LAD, EW, AF, RNF, RP, SG and GGK. Administrative, technical or material support: DG, HWB and SG. Final approval of the manuscript: HMB, HWB, DG, LAD, RP, EW, AF, RNF, SG and GGK.

DISCLOSURES: Dr Becker has no relevant conflicts of interest. Mr Grigat has no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr Ghosh has served as a speaker for Merck, Schering-Plough, Centocor, Abbvie, UCB Pharma, Pfizer, Ferring, and Procter and Gamble. He has participated in ad hoc advisory board meetings for Centocor, Abbott, Merck, Schering-Plough, Proctor and Gamble, Shire, UCB Pharma, Pfizer and Millennium. He received research funding from Procter and Gamble, Merck and Schering-Plough. Gilaad Kaplan has served as a speaker for Janssen, Merck, Schering-Plough, Abbott and UCB Pharma. He has participated in advisory board meetings for Janssen, Abbott, Merck, Schering-Plough, Shire and UCB Pharma. Dr Kaplan has received research support from Abbott and Shire. Dr Dieleman has served as a speaker and consultant for Abbvie and Janssen. Dr Fedorak has served as consultant/advisory board member for Abbvie, Ferring, Janssen, Shire, VSL#3, Celltrion, Hospira, Amgen, Hoffman Roche. He has received research support from Abbvie, Alba, Bristol Myers Squibb, Centocor, GSK, Genentec, Janssen, Merck, Millennium, Novartis, Pfizer, Proctor & Gamble, Roche, VSL#3 and Celltrion. Dr Fedorak is owner/shareholder of Metabolomic Technologies Inc (www.metabolomictechnologies.ca). Ms Fernandes has no relevant conflicts of interest. Dr Panaccione has served as a speaker, a consultant and an advisory board member for Abbott Laboratories, Merck, Schering-Plough, Shire, Centocor, Elan Pharmaceuticals, and Procter and Gamble. He has served as a consultant and speaker for Astra Zeneca. He has served as a consultant and an advisory board member for Ferring and UCB. He has served as a consultant for Glaxo-Smith Kline and Bristol Meyers Squibb. He has served as a speaker for Byk Solvay, Axcan, Janssen and Prometheus. He has received research funding from Merck, Schering-Plough, Abbott Laboratories, Elan Pharmaceuticals, Procter and Gamble, Bristol Meyers Squibb and Millennium Pharmaceuticals. He has received educational support from Merck, Schering-Plough, Ferring, Axcan and Janssen. Dr Barkema has served as a speaker for Merck, Pfizer and Schering-Plough. He has participated in advisory board meetings for AbbVie, Merck and Schering-Plough.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rocchi A, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: A Canadian burden of illness review. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:811–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/984575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jelsness-Jorgensen LP, Bernklev T, Henriksen M, Torp R, Moum BA. Chronic fatigue is associated with impaired health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:106–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04498.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. e42. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. quiz e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh S, Mitchell R. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on quality of life: Results of the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2007;1:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nahon S, Lahmek P, Durance C, et al. Risk factors of anxiety and depression in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2086–91. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graff LA, Walker JR, Lix L, et al. The relationship of inflammatory bowel disease type and activity to psychological functioning and quality of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lix LM, Graff LA, Walker JR, et al. Longitudinal study of quality of life and psychological functioning for active, fluctuating, and inactive disease patterns in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1575–84. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lonnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life – discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benchimol EI, Manuel DG, Guttmann A, et al. Changing age demographics of inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study of epidemiology trends. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1761–9. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almadani SB, Adler J, Browning J, et al. Effects of inflammatory bowel disease on students’ adjustment to college. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:2055–62.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Currie LM, Ronquillo C, Dick T. Access to Internet in rural and remote Canada. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2014;201:407–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neter E, Brainin E. eHealth literacy: Extending the digital divide to the realm of health information. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e19. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pizzi LT, Weston CM, Goldfarb NI, et al. Impact of chronic conditions on quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:47–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mib.0000191670.04605.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knez R, Franciskovic T, Samarin RM, Niksic M. Parental quality of life in the framework of paediatric chronic gastrointestinal disease. Coll Antropol. 2011;35(Suppl 2):275–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janke KH, Raible A, Bauer M, et al. Questions on life satisfaction (FLZM) in inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19:343–53. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0522-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sainsbury A, Heatley RV. Review article: Psychosocial factors in the quality of life of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:499–508. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burisch J, Jess T, Martinato M, Lakatos PL. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:322–37. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negron ME, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996–1006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaplan GG, Seow CH, Ghosh S, et al. Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: A population-based time trend study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1879–87. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billiet T, Rutgeerts P, Ferrante M, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Targeting TNF-alpha for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14:75–101. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2014.858695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones J, Pena-Sanchez JN. Who should receive biologic therapy for IBD? The rationale for the application of a personalized approach. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:425–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moser G, Tillinger W, Sachs G, et al. Relationship between the use of unconventional therapies and disease-related concerns: A study of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:503–9. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilsden RJ, Verhoef MJ, Best A, Pocobelli G. Complementary and alternative medicine use by Canadian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: Results from a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1563–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallinger ZR, Nguyen GC. Practices and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: A survey of gastroenterologists. J Complement Integr Med. 2014;11:297–303. doi: 10.1515/jcim-2014-0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lonnfors S, Vermeire S, Greco M, et al. IBD and health-related quality of life – discovering the true impact. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1281–6. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong S, Walker JR, Carr R, et al. The information needs and preferences of persons with longstanding inflammatory bowel disease. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:525–31. doi: 10.1155/2012/735386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones MP, Bratten J, Keefer L. Quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome differs between subjects recruited from clinic or the internet. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2232–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cantarelli P, Debin M, Turbelin C, et al. The representativeness of a European multi-center network for influenza-like-illness participatory surveillance. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:984. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kontos E, Blake KD, Chou WY, Prestin A. Predictors of eHealth usage: Insights on the digital divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e172. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: Literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:616–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]