Abstract

Macrophages derive from human embryonic and fetal stem cells and from human bone marrow-derived blood monocytes. They play a major homeostatic role in tissue remodeling and maintenance facilitated by apoptotic “eat me” opsonins like CRP, serum amyloid P, C1q, C3b, IgM, ficolin, and surfactant proteins. Three subsets of monocytes, classic, intermediate, and nonclassic, are mobilized and transmigrate to tissues. Implant-derived wear particles opsonized by danger signals regulate macrophage priming, polarization (M1, M2, M17, and Mreg), and activation. CD14+ monocytes in healthy controls and CD16+ monocytes in inflammation differentiate/polarize to foreign body giant cells/osteoclasts or inflammatory dendritic cells (infDC). These danger signal opsonins can be pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs/MAMPs), but in aseptic loosening, usually are damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Danger signal-opsonized particles elicit “particle disease” and aseptic loosening. They provide soluble and cell membrane-bound co-stimulatory signals that can lead to cell-mediated immune reactions to metal ions. Metal-on-metal implant failure has disclosed that quite like Ni2+, its neighbor in the periodic table Co2+ can directly activate toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) as a lipopolysaccharide-mimic. “Ion disease” concept needs to be incorporated into the “particle disease” concept, due to the toxic, immune, and inflammatory potential of metal ions.

Keywords: monocyte, macrophage, dendritic cell, polarization, activation

I. INTRODUCTION

Interactions between implant-derived wear particles and macrophages are considered to be the key events in aseptic loosening.1 With regard to implant design and loosening, much attention has been paid to the role of properties of the particles in this interaction. Less attention has been paid to the effect of tuning of the monocyte/macrophages. Histiocytes are seeded to peripheral tissues during the embryonic and fetal period, and are in part self-replenished in situ in peripheral tissues. Maintenance of tissue macrophages is only in part based on monocytopoiesis in bone marrow, from where monocytes can be mobilized and, via blood, be recruited to peripheral tissues. “Resting” homeostatic macrophages actively handle a huge amount of cells, tissue, and implant debris from patients with joint replacements, phagocytosing “eat me”-type apoptotic opsonin-coated waste. This triggers production of anti-inflammatory and repair factors, which probably explains the satisfactory long-term implant survival in the great majority of the patients.

The harmful effects of “third body wear” in the implant articulation are well recognized. Over 105 polyethylene particles are formed in metal-on-polyethylene (MoP) joints and up to 100 times more metal particles are formed in metal-on-metal (MoM) joints at each step taken with the prosthetic joint.2,3 The “third body wear”-mediated damage of peri-implant tissues and fluids in macro- and micromotion has been rarely discussed.4 It is proposed that the combined effect of biomechanical loading and third body wear damage of tissues leads to the formation, exposure, and release of tissue-derived danger signals, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). Coating of the wear particle surface with danger signal opsonins (instead of apoptotic opsonins) could pave the way for the formation of “angry” macrophages.5 In septic loosening, microbe-derived pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs/MAMPs) could similarly overtake the role of the soothing apoptotic “eat me” opsonins and mark wear particles with “hate me” signals instead. This might initiate pro-inflammatory and harmful priming, polarization, and activation of macrophages in peri-implantitis.

Somewhat surprisingly, experience with resurfacing MoM and large-diameter head MoM total hip replacement (THR) implants has disclosed that metal ions seem to have significant direct toxic and inflammatory effects, especially cobalt ions.6 Cobalt ions can, quite like lipopolysaccharide (LPS), directly activate toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) positive cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). These new modes of action on innate immunity can explain some of the adverse reactions against metal debris (ARMD), which cannot easily be explained only by cell-mediated, delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions mediated by T cells and acquired immunity.7 This justifies the introduction of a new term, “ion disease,” which complements our understanding of the effects of “particle disease” in implant loosening. The outcome of peri-implant reactions is largely, in an unknown way, affected by participation of rather heterogeneous and plastic cells of the innate immune system, such as classical, intermediate, and nonclassical circulating monocytes, and their polarization to M1, M2, M17, Mreg, and other macrophage subtypes, in addition to the nonconventional differentiation (polarization) to monocyte-derived DCs/inflammatory DCs or foreign body giant cells/osteoclasts. This is discussed in the light of currently available information.

II. FORMATION OF MONOCYTE/MACROPHAGES FROM EMBRYONIC STEM AND LIVER CELLS AND HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELLS

Primitive myeloid precursors form during the embryonic development from human embryonic stem and liver cells and colonize the human brain to form macrophage-like microglial cells, where they are self-renewing as a result of local proliferation.8 It was recognized relatively early that the fetal liver also plays a role in the production of monocytes, which give rise to epidermal Langerhans cells, DCs with a migratory potential, replenishing themselves by local proliferation under homeostatic conditions.9,10 During severe inflammation, Langerhans cells can be replenished by bone marrow-derived monocytes that on resolution of the inflammation may be ultimately again outcompeted by Langerhans cells of fetal origin.11,12 Early embryonic monocytes and macrophage precursors appear to participate much more widely to the seeding and, later, to local maintenance of adult tissue macrophages than has been previously recognized.13 These early embryonic and fetal monocytes are not classical CD14++CD16− monocytes, but proliferating CD14lowCD16− precursors, which can produce non-proliferating and more mature CD14+CD16+ monocytes, which overlap with adult nonclassical monocytes. Compared to adult blood monocytes, they seem to be involved in anti-inflammatory functions, scavenging, tissue remodeling, and angiogenesis. Macrophages derived from embryonic stem and liver cells might include alveolar macrophages of the lung, sinusoidal lining cells in the spleen, Kuppfer’s cells of the liver, and more or less many other tissue histiocytes in noninflamed healthy tissues.

According to the conventional view, monocytes in the adult bone marrow are formed by stepwise differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors in colony forming units (CFUs) with steps being taken at each decision point driven by one or more, and as yet incompletely known, colony stimulating factor (CSF)-type growth and differentiation factors and by the dynamic niche and colony forming unit-like micro-milieus. During each developmental stage, these cells display a different phenotype defined by characteristics like cytokines, surface receptors, and transcription factors.

Long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells (LT-HSCs) maintain stemness and reside in the endosteal niches maintained by spindle-shaped N-cadherin+ (and CD45−) osteoblastic SNO cells and CXCL12-abundant reticular CAR cells. CXCL12 is also known as stem cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1). In a multistep process, driven first in part by stem cell factor (SCF, also known as c-KIT ligand), CD34+pluripotent endosteal LT-HSC produce, by asymmetric cell divisions, pluripotent and differentiation committed short-term HSCs (ST-HSC). They reside in the perivascular niche maintained by nestin+ mesenchymal stem cells (NES+ MSCs), CAR cells, sinusoidal endothelial cells (SECs), and adventitial reticular cells (ARC), close to outlet to blood. These ST-HSCs soon mature via multipotent progenitors (MPPs) to common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), which form granulocyte, erythrocyte, monocyte, and megakaryocyte-CFUs (CFU-GEMM). Under the influence of multi-CSF (= interleukin-3/IL-3), granulocyte-macrophage CSF (GM-CSF), and other myeloid CSFs, CMPs differentiate further to a new and more restricted lineage consisting of granulocyte and macrophage progenitors (GMPs) forming granulocyte macrophage CFUs (CFU-GM). GM-CSF and macrophage-CSF (M-CSF or CSF-1) drive GMP to proliferate and form macrophage CFUs (CFU-M). Under the influence of M-CSF, cells in these units differentiate to and survive as monoblasts, promonocytes, early monocytes, and monocytes.14 Monoblasts are in some texts called macrophage-dendritic cell precursors (MDPs). Human bone marrow releases three different types of monocytes.

III. HOMEOSTATIC MACROPHAGES

In tissue, classical inflammatory monocytes die if they are not supported by their survival factor M-CSF; however it may be that the homeostatic M0 macrophages are, to a large extent, seeded already during the embryonic and fetal stage and renew locally via proliferation. The local micro-milieu further shapes the proliferation, differentiation, and maturation of colonizing monocytes to heterogeneous local homeostatic tissue macrophages, which is one prominent example of the plasticity of the macrophages.

Local homeostatic tissue macrophages are necessary to tissue remodeling and renewal and exert anti-inflammatory functions.15 Homeostatic macrophages (and other efferocytic cells) take up daily a huge number of apoptotic bodies and other debris that expose phosphatidylserine as a result of membrane phospholipid flipping. They are formed from 50–70 × 109 cells undergoing programmed cell death each day. This type of phagocytosis is called efferocytosis and occurs via the phosphatidyl serine receptors of the homeostatic macrophages. In response to contact with and internalization of apoptotic cells and bodies, homeostatic macrophages produce anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and repair products, such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β).16 It has been estimated that the whole human body contains 10 × 1012 cells. If so, it would take only 200 days to renew 10 × 1012 cells at a 50 × 109 cells/day apoptotic rate.

Apoptotic cell rests are formed as a result of condensation and fragmentation of nuclei (pyknosis and karyorrhexis) and of cytoplasm (condensation and blebbing of apoptotic bodies). During the process, the apoptotic cellular rests start to expose various structures, which may also bind soluble “eat me” pattern recognizing receptors/proteins (sPRRs or sPRP) or opsonins, like CRP, serum amyloid P, C1q, C3b, IgM, MBL, ficolin and some surfactant proteins.17 Late apoptotic cells may also release “find me” signals, which facilitate the contact between apoptotic rests and homeostatic macrophages. This contrasts with the “detach” and “do not eat me” molecules such as CD31 and CD47 expressed on the surface of intact cells.18

Red blood cells flow 300–400 km during their 100- to120-day-long lifetime, meaning that sinusoidal lining cells of the spleen handle 3 kg hemoglobin and iron each year. In addition to this debris come platelets, inhaled dust, and debris derived from remodeling, degenerating, or injured tissues, which all need to be handled.

Homeostatic macrophage probably also participate in the maintenance of the commensal microbial flora of the human body. The total number of bacterial cells in the human body has been estimated to be 100 × 1012. Thus, “the human body” is an ecosystem composed of almost 90% of bacterial cells and containing only 10% eukaryotic human cells.19 This homeostatic function of the human macrophages has received too little attention.

IV. MOBILIZATION OF ADULT MONOCYTES FROM BONE MARROW TO BLOOD

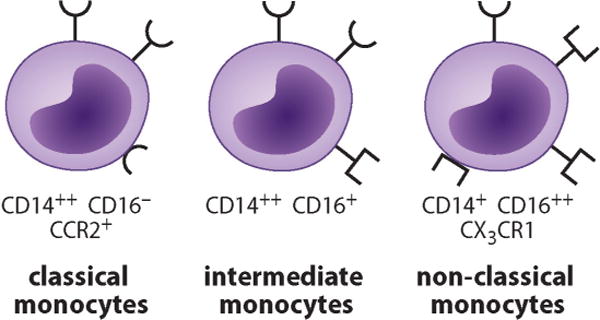

In the resting human body, 5 × 109 monocytes egress to blood each day to form 1–10% of the circulating peripheral blood leukocytes; 85% of the peripheral blood monocytes are CD14++(~100-fold above the isotype control) and CD16− classical monocytes (Fig. 1). CD14 is a lipopolysaccharide co-receptor and in its soluble form sCD14 a soluble pattern-recognizing protein opsonizing apoptotic cells. Egress of these classical bone marrow monocytes to blood is greatly enhanced via danger-associated molecular patterns (either pathogen-associated molecular patterns or endogenous alarmins), which stimulate TLR positive peripheral tissue cells to produce CCL2, which then triggers monocyte exit to blood.20 These somewhat immature classical “inflammatory” CD14++ and CD16− monocytes are characterized by CCR2-type chemokine receptors and are thus effectively mobilized by CCL2 (= macrophage chemotactic peptide-1 or MCP-1) and MCP-3.21 Because of the local production of M-CSF in inflamed tissues, a high proportion of the M-CSFR+ (= CSF-1R) proliferative and anti-apoptotic classical monocytes survive and proliferate in tissue, which further increases their numbers.

FIG. 1.

At present, monocytes in peripheral blood are classified to three subsets. The major subset is formed by classical monocytes that are defined to be strongly CD14 positive but CD16 negative. They are characterized by CCR2-type chemokine receptors. Intermediate monocytes are defined by their strong CD14 positivity, but also low CD16 positivity. They also express a large majority of genes and surface markers at intermediate levels compared to classical and nonclassical monocytes (not shown). Finally, nonclassical monocytes have relatively low CD14 expression but strong CD16 expression. They also express strongly CX3CR1-type chemokine receptors.

If classical inflammatory monocytes are allowed to mature for a longer time in bone marrow, they form CD14++CD16+ (~10-fold above the isotype control) intermediate monocytes and finally even more mature CD14+CD16++ nonclassical monocytes (Fig. 1), together termed CD16 monocytes. CD16 is an FcγRIII involved in phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized particles. CX3CR1 and other chemokine receptors are expressed by intermediate monocytes, which form ~5% of all monocytes, and in particular by nonclassical monocytes, which form ~10% of all blood monocytes.22 Nonclassical monocytes have an anti-proliferative, pro-apoptotic phenotype. CX3CR1+ monocytes are mobilized by the soluble form of their chemokine ligand fractalkine (CX3CL1), which forms their major mobilization pathway from the bone marrow.

V. NONCLASSICAL, INTERMEDIATE, AND CLASSICAL MONOCYTES

CCR2+CD14++ classical inflammatory monocytes are marginalized close to post-capillary venous endothelial cells.22 Relatively rapidly, within 8–16 h, they develop the initial leukocyte-endothelial cell contact and start to tether and then roll rapidly at a 40 μm/s rate, which is 100- to 1000-fold faster than crawling. This is based on expression of L-selectin by inflammatory monocytes, which enables rapid and dynamic binding and detachment cycles to carbohydrate ligands on the wall of the endothelium, together with monocyte Int α4β1 (VLA-4, very late activation antigen) and endothelial cell VCAM-1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, CD106) interactions. CCL2/MCP-type chemokine ligands bind to CCR2, which activates leukocyte integrins and signal transduction leading to arrest, adhesion post-adhesion strengthening, and finally crawling along the endothelium using Int αLβ2 (LFA-1/leukocyte functional antigen-1; CD11a/CD18) and Int αMβ2 (Mac1, CF3, CD11b/CD18) and their ligands, such as ICAMs (intercellular adhesion molecules). Finally, transmigration through and detachment from the endothelium to tissues ensue. This allows effective recruitment of inflammatory monocytes to peri-implant tissues.23 Because of the local production of M-CSF in inflamed tissues, a high proportion of the M-CSFR+ (= CSF-1R) proliferative and anti-apoptotic classical monocytes survive and proliferate in tissue, which effectively further increases their numbers. Classical inflammatory monocytes have the broadest range of sensing receptors and diverse capacities to produce a wide range of chemokines and cytokines such as IL-6, IL-8, and G-CSF but also participate in tissue repair and to produce IL-10.24 In peri-implant infections, apparently other leukocytes, such as PMNs and T and B lymphocytes, are also recruited. If metal ions form a significant source of irritation, lymphocytes and eosinophils are effectively recruited to peri-implant tissues.25

It is not known at what stage the CD14++CD16+ intermediate monocytes migrate from the blood to tissues. They have an intermediate expression of 87% of genes and surface markers expressed by nonclassical and classical monocytes. There is a tentative developmental maturation of classical monocytes to intermediate and further to nonclassical monocytes. It might be that the intermediate monocytes use both nonclassical and classical strategies for transmigration. Intermediate monocytes have high expression of major histocompatibility class II (MHC II) and co-stimulatory CD40 molecules, and thus a well-developed antigen presenting potential.

The nonclassical CX3CR1+CD14+CD16++ monocytes are also called resident monocytes because they stay for one to three days in the circulation. They are not freely circulating “floating” cells passively carried by the bloodstream, but attach to resting endothelium inside arteries, capillaries, postcapillary venules, and veins, where they crawl along and against the mainstream blood flow. This occurs slowly at a speed of 4–20 μm/min, in complicated surveillance paths forming loops, hairpins, waves, and various mixed movement patterns. CX3CR1+ resident monocytes are first attracted to the transmembrane form of the endothelial chemokine fractalkine (CX3CL1), which then activates the leukocyte IntαLβ2 (= CD11a/CD18 = LFA-1). Crawling along the epithelial surface seems to be dependent on IntαLβ2 and requires a well-organized and strong cytoskeleton.26

Although extravasation of resident or patrolling nonclassical CD14+CD16++ monocytes is rare in a resting state, on endothelial injury they transmigrate at a very early stage through the damaged endothelium to tissues. This so-called early inflammation is followed by invasion of polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMNs), and thereafter, an acute-to-chronic shift occurs by invasion of CCR2+ CD14++ inflammatory monocytes.27 Due to their location, resident monocytes can respond to an endothelial and tissue insult in only 1–2 h by transmigration. They produce tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) more effectively than other monocytes, especially in response to LPS. This early phase of inflammation prepares endothelial adhesion molecules to subsequent recruitment of PMNs. By 8 h after the infectious insult, resident monocytes cease to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and initiate repair.26

Continuation of the host response depends then on the strength of the noxious stimulus and the outcome of the initial host defense response. After the very rapid resident monocyte response and the acute IL-8-dominated and PMN-rich response, neutrophils start to function as a source of soluble interleukin-6 receptor type A (sIL-6RA). This binds to locally produced IL-6. The soluble complex formed trans-signals to the IL-6RB+ endothelial cells change their adhesion molecule profile so that neutrophil recruitment decreases and recruitment of inflammatory monocytes takes over during the chronic, mononuclear cell-rich phase of the host response.28 If IL-6 binds to cell surface IL-16RA, two IL-6RB (gp 130) chains are rapidly recruited to activate the downstream signaling in some cells like hepatocytes, monocytes, neutrophils, and some T and B cells. However, in most cells a soluble IL-6/IL-6RA complex stimulates IL-6 receptor negative cells if they contain the signaling IL-6RB chain, which are rapidly recruited and signaling is initiated. Such signaling is known as trans-signaling.

VI. MACROPHAGE PRIMING

Low concentrations of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) from, e.g., natural killer T cells (NKT cells) can prime homeostatic macrophages. Homodimeric IFN-γ binds to two ligand binding IFN-γR α-chains, which engage two signaling IFN-γR β-chains and the associated Janus kinases JAK1 and JAK2, respectively. They phosphorylate, bind, and activate a signal transducer and activator of transcription-1α. STAT1α detaches from the activation complex and translocates as a homodimeric gamma-interferon activating factor GAF to the nucleus, where it binds to gamma activated site GAS initiating transcription. Primed macrophages are not activated but they are tuned to respond to subthreshold stimuli and with an enhanced signal-response ratio to suprathreshold stimuli. We have speculated that the low background level of IFN-γ production by, e.g., NKT cells and Th1 T cells could prime macrophages to very strong responses against subsequent second stimuli, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or endogenous danger signals (alarmins, for example, low molecular weight hyaluronan or biglycan) in diseases like RA or implant loosening.29 Similar synergism might work between IL-17 and TNF-α.30

VII. M1, M2, M17, AND MREG POLARIZATION

Polarization is not simply macrophage activation but exclusive selection of a differentiation path among several possible options. The term polarization has been borrowed from immunology, which due to the diversity and volatility of macrophage phenotypes may not be quite appropriate. Th0 cells are polarized to Th1 cells by IFN-γ and IL-12. Typically, polarizing cytokines are initially provided by cells of the innate immune system, such as NKT cells and macrophages.31 Later on, Th1 cells produce IFN-γ in ample quantities, thus consolidating their own polarization. Th1 cells participate in host defense against intracellular pathogens. Alternatively, Th0 cells are polarized to Th2 cells by IL-4 and IL-13 derived from innate mast cells and basophils.32 This polarization is consolidated by Th2 cell-mediated production of IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13. Th2 cells participate in host defense against extracellular pathogens and allergens. IL-6, TGF-β, and IL-23 polarize Th0 cells to Th17 cells, which however produce IL-17 and IL-22 and fight extracellular pathogens such as Candida, in particular in various epithelial structures. IL-10 and TGF-β polarize Th0 cells to Treg cells, which produce immunosuppressive IL-10 and TGF-β.

Addition of TNF-α to IFN-γ primed macrophages or exposure of homeostatic M0 macrophages to larger and directly pro-inflammatory doses of IFN-γ or TNF-α and LPS drives them in vitro to a classically polarized state with a strong inflammatory effector cell potential, to M1 macrophages. Innate immune cells form a transient source of, e.g., IFN-γ and TNF-α leading to a rapid and transient M1 polarization. Long-term maintenance of M1 macrophages requires IFN-γ and IL-12 production by Th1 cells of the adaptive immune system. M1 macrophages produce chemokines, such as CCL2-4 and CXCL8-11, which augment the pro-inflammatory host potential by attracting Th1 cells via chemotaxis. They produce distinct pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23. M1 polarized cells are characterized by intracellular machineries enabling an effective intracellular microbicidal activity, e.g., via induction of iNOS, which produces reactive nitrogen species and L-citrulline from arginine. Finally, M1 macrophages increase their cell surface MHC II and co-stimulatory CD80 and CD86 markers, augmenting their potential to present antigens in cell-mediated immune responses.

Inflammatory doses of IL-4 drive M2 polarization to alternatively activated healing macrophages, which are also engaged in helminthic infestations. IL-4 and IL-13 can be transiently derived from innate mast cells and basophils, but long-term consolidation of an M2 phenotype requires production of these polarizing cytokines by Th2 cells. M2 polarization is associated with suppressed production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, intracellular killing, and antigen presentation. M2 macrophages secrete chemokines like CCL17, CCL18, CCL22, and CCL24, which recruit Th2 cells, basophils, and eosinophils.33 They also produce moderate levels of IL-10. Membrane receptors with scavenger function are upregulated, together with a variety of molecules implicated in tissue regeneration, wound healing, granuloma formation, and immunity against large parasites.34 Induction of arginase 1 in M2 polarization leads to production of L-ornithine utilized to produce polyamine and proline used for collagen synthesis.35 By producing and organizing components of extracellular matrix, M2 macrophages can seal extracellular pathogens by fibrosis. A type 2 environment favors IgG1 production in the presence of IFN-γ. IgE and IgG4 production is favored by IL-4 and or IgA production by IL-5 in allergies and expulsion reactions.

The M17 macrophage concept is relatively new.36 Macrophages induced by corticosteroids or by M-CSF and IL-10, when treated with IL-17, become resistant to apoptosis, which enables efficient clearance of apoptotic cellular rests. Apoptotic cells, IL-10, corticosteroids, TGF-β, and immune complexes, when used for stimulation together with TLR agonists, initiate deactivation29 or Mreg polarization,31 which is maintained by IL-10 produced by Treg cells. Regulatory macrophages exert regulatory anti-inflammatory effects.

In this context, it is interesting that classical and novel polarizing cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-4, GM-CSF, and IL-17A, are low in peri-implant tissues compared to control osteoarthritic synovial membrane. In contrast, there is a significant upregulation of M-CSF, CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, IL-8, IL-10, TRAP, and cathepsin K, but downregulation of OPG. These findings suggest that monocyte recruitment and osteoclast formation are prominent and that factors other than the classical polarizing cytokines drive aseptic loosening.37

VIII. MACROPHAGE ACTIVATION

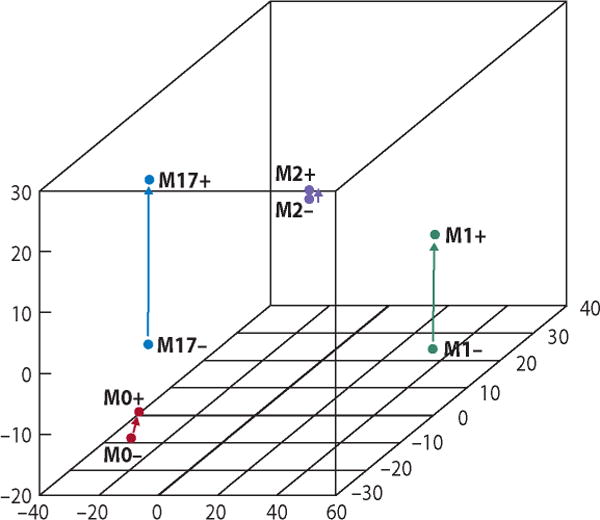

Polarized macrophages are activated according to their polarization state by phagocytosis of particulate matter. Effects of phagocytosis on polarized macrophages are regulated by eventual apoptotic (see above), nonimmune (apoptotic signals, C-reactive protein, serum amyloid P, mannan, fibronectin, vitronectin, danger signals, etc.) and immune (immunoglobulin, complement) opsonins (“eat me” signals) coating the surface of the particles. M0, M1, and M2 polarized macrophages are differently activated in response to LPS-free TiO2 particles (Fig. 2).38 In the host response to implant-derived wear debris or pathogens, one major factor is the phenotype of the macrophages engaged in these host responses.

FIG. 2.

Macrophage polarization affects their response to a subsequent particle-mediated activation. In this experiment, M0 macrophages were produced from human peripheral blood monocytes by stimulation with macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF). M1, M2, and M17 macrophages were produced from M0 macrophages by further stimulation of M0 macrophages with interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-4 (IL-4), and interleukin-17 (IL-17), respectively. 3D scaling image shows separation of these polarization states from each other. Furthermore, the type and intensity of their responses to a subsequent stimulation with phagocytosable TiO2 particles was dependent on their polarization state.

IX. DIFFERENTIATION (POLARIZATION) TO MULTINUCLEAR GIANT CELLS

If macrophage polarization is coherently considered as cellular plasticity providing the macrophage-derived polarized cells with unique abilities and reaction patterns, also formation of multinuclear giant cells should be considered as a form of macrophage polarization.39

Bone around joint implants is remodeled or resorbed by bone multicellular units (BMUs) undergoing activation-reversal-formation (ARF) cycles in bone remodeling compartments (BRCs). Implantation- and microfracture-induced damage of osteocytes, forming over 95% of bone cells, probably acts as the sensory element and initiates the formation, regulates the number, and determines the direction of movement of the BMUs. BMUs in osteons in cortical bone and in hemi-osteons in trabecular bone contain bone resorbing osteoclasts and bone forming osteoblasts in the cutting and closing cones, respectively.

TNF-α and IL-1β induce receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) on immature mesenchymal bone stromal cells.40 In the presence of M-CSF, RANKL drives RANK+ and CD14+ osteoclast precursors in healthy controls to osteoclasts, i.e., to fuse to multinuclear cells,41,42 if a soluble decoy receptor osteoprotegerin does not neutralize it.43 However, in arthritis, osteoclasts may form from CD16+ monocytes or GM-CSF and IL-4 induced immature DCs that also express CD16.44 The same may apply to aseptic loosening.45 Osteoclasts express integrin β3 subunit, calcitonin receptor, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), and cathepsin K, and are able to resorb bone. Bone resorbing osteoclasts are formed in contact with peri-implant bone and foreign body giant cells with wear debris.

X. POLARIZATION TO MONOCYTE-DERIVED MYELOID DENDRITIC CELLS

MHC II+ and MHC I+ but lineage negative (negative for CD3 T-cell, CD19/20 B-cell, and CD56 NK-cell markers) DCs are necessary for antigen-specific activation of naive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Whereas other APCs are typically sensitive to micromolar concentrations of antigens, macropinocytosis and receptor-mediated endocytosis make antigen capture by DCs so effective that even nanomolar to picomolar concentrations of antigen can suffice to elicit T-cell responses.46 Immature myeloid DC-like cells (monocyte-derived MoDCs) are produced from blood monocytes in vitro using GM-CSF and IL-4. Reverse-migrating veiled cell-type DCs of afferent lymph are produced from human blood monocytes in endothelial cell/collagen matrix culture, particularly if stimulated with phagocytosis.47 Monocytes that are injected subcutaneously to phagocytose particulate antigen become DCs migrating via afferent lymphatics to the paracortical T-cell areas in the draining lymph nodes.48 Nonclassic and intermediate CD16+ monocytes have the greatest propensity to develop to migratory MoDCs.49 Some “interstitital” DCs in tissues and lymph nodes may arise from classical CD14+ monocytes, with CD14 being lost and CD209 (DC-SIGN) induced upon DC maturation.50,51 Inflammatory DCs (infDCs) from inflammatory synovial or ascites fluids are derived from human monocytes and are reminiscent of in vitro produced MoDCs rather than conventional DCs although this study could not address their origin from classical, intermediate, and/or nonclassical monocytes.52 The professional antigen-presenting DCs express MHC II/peptide complex at 10- to 100-fold higher amounts than other antigen-presenting cells, such as macrophage and B cells, so that also antigen presentation by DCs is very effective.53

Although blood monocytes and blood DCs form distinct cellular subsets, their functional relationship in immuno- and tolerogenic immune responses is unclear. Committed “dendritic cells” or pre-DCs in blood are derived from hematopoietic progenitors. Blood myeloid DCs derive from macrophage and dendritic cell precursor (MDP), which stimulated by fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand FLT3L differentiate first to common dendritic cell precursor (CDP) and then to pre-DCs, which enter the bloodstream. Plasmacytoid DCs are perhaps also derived from CDP or from common lymphoid progenitor (CLP). Pre-DCs are in blood round cells in transit to lymphoid tissue, with a potential to develop to professional antigen surveilling, capturing, processing, and presenting cells (APCs). They form only ~1% of blood cells and are divided into three populations. Under homeostatic conditions, all three pre-DC subsets pass from blood to lymphoid organs (spleen and lymph nodes) via high endothelial venules (HEVs). In lymphoid tissue, they are lymphoid tissue-resident classic (conventional) DCs. Under inflammatory conditions, they may pass to peripheral tissue, probably via HEV-like vessels. Blood myeloid pre-DCs contain myeloid markers (CD13, CD33), lack monocyte markers (CD14, CD16), and are either CD1c+ or CD141+. CD1c (BDCA-1) is involved in the presentation of glycolipid antigens of mycobacteria, but these mDC1 are best known for their capacity to stimulate naive CD4+ T cells. CD141+ (BDCA-3) mDC2 are characterized by TLR3, which recognizes ds-RNA leading to IFN-λ production and cross-presentation of, e.g., viral antigens to cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. CD303+ plasmacytoid DCs lack myeloid markers and are TLR7+ and TLR9+ natural type I interferon-producing cells. CD303 is blood dendritic cell antigen 2 (BDCA-2), a type II Ca2+-dependent (C-type) lectin.

Peripheral nonlymphoid tissues such as skin, lung, and intestine contain sentinels known as migratory DCs, which are also of hematopoietic origin. It was already mentioned above that Langerhans cells of the skin are derived early during development from a progenitor in the fetal liver. They sample their environment and migrate then to their draining lymph nodes (secondary lymphatic tissue) via afferent lymphatic vessels to induce either tolerogenic or immunogenic host immune responses. Migratory DCs are mobile cells compared to rather sessile macrophages, which do not usually migrate out from their tissue of residence.

In interface tissue around loose implants, 1–2 % of local leukocytes are DCs, probably mostly the above-mentioned CD14+ monocyte-derived inflDC because at least CD209+ (DC-SIGN) DCs have been described in peri-implantitis.51,54 This is supported by the findings that demonstrate that CD14+ CD16+ monocytes are increased in periprosthetic tissues in aseptic loosening compared to mechanical loosening, stable implants, or osteoarthritis.45 Indeed, GM-CSF-produced moDCs initiate a two-stage response on contact with oxidized polyethylene wear debris. Oxidized PE stimulates MHCII, IL-12, pro-IL1β, and pro-IL-18 production, probably via direct stimulation of TLR1/2 on the DC surface. Due to phagocytosis of indigestible PE and subsequent phagolysosomal damage, cathepsins released into cytosol activate the NALP3 (or cryopyrin) inflammasome. This activates, via caspase-1 (interleukin-1 converting enzyme/ICE), pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, which are released in their active form. These events contribute to periprosthetic inflammation, osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, and ultimately aseptic osteolysis.55

XI. FROM DANGER SIGNALS TO ION DISEASE

Aseptic loosening with osteolysis was first called “cement disease” due to the effects of fragmented bone cement; because non-cemented metal-on-PE implants associated with polyethylene wear also lead to a similar type of osteolysis (sometimes without loosening), the name was converted later to “particle disease.”56–58 As discussed above, the homeostatic macrophages around implants should have a very high capacity to capture and contain implant-derived debris and respond by production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, without causing any inflammation. Indeed, most prosthetic joints serve several decades without loosening. In some patients, wear debris leads to “particle disease,” which is a chronic inflammatory and foreign body reaction. It may be that the particles per se or coated by apoptotic “eat me” opsonins are innocent, but if they are instead coated by opsonizing danger signal “patterns” from damaged tissues, they might lead to chronic foreign body inflammation. “Pattern” is used here to emphasize the broad receptor binding capacity of the pattern recognizing receptors, which contrasts to the specific perfect fit lock-and-key antigen-to-immune receptor binding.

Danger-associated molecular patterns can be exogenous pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or actually microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) because our normal flora also contains patterns similar to those found in pathogens. Such patterns might reach peri-implant tissues by direct contamination or bacteremia. Microbes might easily colonize the abiotic implant surface and form dormant biofilms.59,60 These would not necessarily lead to an overt infection, but might form a continuous local source of PAMPs/MAMPs. Such microbial danger signals do not need to be components of living whole microbes because, for example, lipopolysaccharide in periodontitis is released into the circulation in relation to the area of the affected periodontital tissue.61

Another major class of danger-associated molecular patterns are endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs or alarmins). Their formation might be increased by the “third body wear”-mediated damage, i.e., not of the implant, but of peri-implant tissues. DAMPs are components of the extracellular matrix or cells, which are exposed, released, or denatured and recognized as signs of local tissue damage, alarming the cells via pattern recognizing danger receptors to some type of host response. Such a host response probably leads to remodeling and repair in the short run, but if the release of DAMPs continues for a long time, this host response might lead to chronic inflammation. These DAMPs include oxidized LDL (low density lipoprotein), SAA (serum amyloid A), vercican, biglycan, low molecular weight hyaluronan, tenascin C, various heat shock proteins, HMGB1 (high mobility group box 1), neutrophil elastase, lactoferrin, and heparin sulphate, to mention some of the potential ligands.62

Detection of danger signal receptors belonging to the TLR family and recognition also of endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns as their potential ligands has stimulated new ideas concerning innate immunity, auto-inflammation and auto-inflammatory diseases. TLRs are primarily either cell membrane-bound (TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR6) or endosomal (TLR3, TLR7, TLR8, TLR9). The former are able to recognize exposed microbial surface patterns (structures) such as lipopeptides, lipoteichoic acid, flagellin, peptidoglycans, or LPS, whereas the latter recognize internal and hidden microbial structures derived from genetically important double- or single-stranded DNA and RNA patterns. Other newly discovered pattern recognizing receptors are cytosolic NLR (NOD/nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors), RLR (RIG/retinoid acid inducible gene-I-like receptors), AIM2 (absent in melanoma-2) receptors, and numerous other new intracellular nucleic acid receptors (sensors). Furthermore, PRRs also comprise Ca2+-dependent C-type lectins (mannose receptors and asialoglycoprotein receptors).

Danger signaling regulates inflammation. At present, there is much focus on how danger signaling leads to robust production of various chemo- and cytokines and cell surface molecules, which are pro-inflammatory but also provide co-stimulation for adaptive immune responses. Thus, in the human body this system has a dual function. The auto-inflammatory component of the response seems to be a broad-based rapid and robust, but soon downregulated, and rather uniform first line innate-inflammatory host response. Under homeostatic conditions it also seems to be able to maintain the epithelial barrier function and the commensals on human skin and mucous membranes. This auto-inflammatory response also provides the co-stimulation (by convention “signal two”), which is necessary for antigen presentation (“signal one”) to be able to lead to antigen-specific adaptive immune responses.

As outlined above, the effects of various apoptotic “eat me” and “find me” opsonins were emphasized. With regard to “particle disease,” opsonizing “hate me” danger signals probably play a pathogenic role. Danger signals are recognized by various pattern recognizing receptors, in particular TLRs. They usually activate the cell via a Myd88-dependent pathway although TLR3, which is only TLR using the TRIF-dependent pathway, may naturally also be relevant. TLR4 is the only TLR that uses both MyD88 and TRIF signaling. Aseptic loosening may start as a biomechanical process, leading to implant wear, stress, and strain associated with implant loading and fluid pressure waves (pressure theory of loosening), in particular in non-optimally implanted (e.g., surgical issues) or otherwise strained (e.g., obesity) joint prosthesis. Increased implant loading will increase the particle burden and the volume and extent of the effective joint space around a loosened implant via which the particles produced at implant surfaces can spread also elsewhere around an implant.63 In particular, such biomechanical loading and wear debris can together at the implant-host interface cause “third body tissue wear” and damage. This leads to release, production, and exposure of extracellular matrix- and cell-derived danger signals. These signals can then opsonize wear particles for recognition by TLRs (and other pattern recognizing receptors), leading to inflammatory responses against the wear particles. This opsonization with danger signals could be an alternative to the apoptotic opsonization/opsonins and non-inflammatory handling of implant-derived wear particles.

Recent clinical problems with metal-on-metal hip resurfacing and total hip replacements that use large-diameter heads are caused by adverse reactions to metal debris (ARMD), many of which relate to metal ions rather than metal particles. These pathological reactions are related to the special wear mode of metal implants and particles, namely, their electrochemical corrosion in the human body fluids.64 One of the many consequences of the relatively loosely bound and nondirectional electron clouds in metallic bonds around the atomic metal cores is detachment of outer shell valence electrons and dissolution of metal ions in at least eight different modes of corrosion.65

Ion-related complications have been traditionally associated with delayed cell-mediated hypersensitivity reactions against metal ion hapten-modified self-peptide in a complex with the MCH II on the antigen-presenting surface of professional APC/DCs. These modified-self epitopes are then recognized as non-self by the highly accurate (specific) T-cell receptors in, e.g., cobalt-specific contact hypersensitivity. This first happens in T-cell-dependent areas of secondary lymphatic tissues, e.g., in local lymph nodes. Lymphocyte recirculation from blood via HEV to and through the lymph node and then via the efferent lymphatic vessels back to blood facilitates both the sensitization (immune detection) and the dissemination of the already acquired immune memory, e.g., after metal sensitization to peri-implant tissues. ALVALs (aseptic lymphocyte-dominated vasculitis-associated lesions) or LYDIAs (lymphocyte-dominated immunological answers) could represent these types of delayed cell-mediated hypersensitivity responses.25

Metal ions could also bind to intact or partially degraded proteins and alter their proteolytic or oxidative cleavage pattern (degradation) so that the “business as usual” immunodominant and tolerogenic antigenic determinants are replaced by cryptic and immunogenic determinants. A third option is chemical or conformational cobalt ion-mediated modulation of the 3D structure of the self-MHC II (“tissue type” antigens) as is seen in hard metal disease. Such metal hapten-altered HLA-DP-type MHC II molecules would be considered by T cells as alloantigens and be “rejected.” Finally, at least Ni+ ions can directly cross-link HLA-DRβ chain and complementarity-determining regions of the T-cell receptor α-chain. This can lead to peptide-independent polyclonal T-cell activation as is seen in staphylococcal superantigen-mediated T-cell responses.66

In spite of evidence of the potential role of metal hypersensitivity in aseptic loosening, these types of reactions are probably rather rare. Therefore, other mechanisms should be sought. Cobalt has at higher concentrations even direct systemic neurotoxic effects such as blindness, deafness, peripheral neuropath, y and cognitive decline.6 Similarly, cobalt cardiomyopathy is a well-recognized systemic toxic effect. Toxic effects in general are directly dose dependent, suggesting that local toxicity should be particularly likely and could explain phenomena like cellular and tissue necrosis and fluid collections in peri-implant tissues.

An exciting new hypothesis has been opened by findings that demonstrate direct effects of cobalt ions on TLR4 as LPS mimics. This phenomenon was first detected for Ni2+ ions. This explains why mice, unlike humans, require co-administration of adjuvant to generate cell-mediated hypersensitivity to Ni2+. Nickel ions can directly activate human TLR4 but not mouse TLR4.67 Similar to Ni2+, Co2+ also has direct irritant capacity. It was then further noticed that, according to the periodic table of the elements, Co2+ should have similar chemical reactivity to that of Ni2+, which was also reported to be the case.68,69 This may have important implications for peri-implantitis and implant loosening, in particular for MoM implants, both resurfacing and large-diameter head THR.7 In contrast to Co2+, LPS-mediated sTLR4 binding and dimerization requires MD2. Therefore, sTLR4 does not inhibit LPS-dependent cell membrane-mediated TLR4 responses. Co2+ binds soluble MD2-free TLR4 and causes its dimerization. Therefore, sTLR4 exerts competitive inhibition of Co2+-driven activation of cell membrane TLR4.70 Thus, it seems necessary that metal ions and “ion disease” need to be incorporated into the “particle disease” concept, due to their toxic, immune, and inflammatory potential.

XII. SUMMARY

Our understanding of important concepts related to orthopedic implant osseointegration, loosening, and periprosthetic osteolysis has matured to encompass complex biological, chemical, immunological, material, and biomechanical phenomena. Further research will undoubtedly advance our knowledge in these areas, with the hope of improving patient outcomes after joint replacement procedures.

References

- 1.Nich C, Takakubo Y, Pajarinen J, Ainola M, Salem A, Sillat T, Rao A, Raska M, Tamaki Y, Takagi M, Konttinen Y, Goodman SB, Gallo J. Macrophages—key cells in the response to wear debris from joint replacements. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2013;101(10):3033–45. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKellop HA, Campbell P, Park SH, Schmalzried TP, Grigoris P, Amstutz HC, Sarmiento A. The origin of submicron polyethylene wear debris in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995;311:3–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sieber HP, Rieker CB, Köttig P. Analysis of 118 second-generation metal-on-metal retrieved hip implants. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(1):46–50. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b1.9047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKellop HA. The lexicon of polyethylene wear in artificial joints. Biomaterials. 2007;28(34):5049–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakshit DS, Lim JT, Ly K, Ivashkiv LB, Nestor BJ, Sculco TP, Purdue PE. Involvement of complement receptor 3 (CR3) and scavenger receptor in macrophage responses to wear debris. J Orthop Res. 2006;24(11):2036–44. doi: 10.1002/jor.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Simonsen LO, Harbak H, Bennekou P. Cobalt metabolism and toxicology–a brief update. Sci Total Environ. 2012;432:210–5. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konttinen YT, Pajarinen J. Adverse reactions to metal-on-metal implants. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2013;9(1):5–6. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler MF, Conway SJ, Ng LG, Stanley ER, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330(6005):841–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chorro L, Sarde A, Li M, Woollard KJ, Chambon P, Malissen B, Kissenpfennig A, Barbaroux JB, Groves R, Geissmann F. Langerhans cell (LC) proliferation mediates neonatal development, homeostasis, and inflammation-associated expansion of the epidermal LC network. J Exp Med. 2009;206(13):3089–100. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeffel G, Wang Y, Greter M, See P, Teo P, Malleret B, Leboeuf M, Low D, Oller G, Almeida F, Choy SH, Grisotto M, Renia L, Conway SJ, Stanley ER, Chan JK, Ng LG, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M, Ginhoux F. Adult Langerhans cells derive predominantly from embryonic fetal liver monocytes with a minor contribution of yolk sac-derived macrophages. J Exp Med. 2012;209(6):1167–81. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagao K, Kobayashi T, Moro K, Ohyama M, Adachi T, Kitashima DY, Ueha S, Horiuchi K, Tanizaki H, Kabashima K, Kubo A, Cho YH, Clausen BE, Matsushima K, Suematsu M, Furtado GC, Lira SA, Farber JM, Udey MC, Amagai M. Stress-induced production of chemokines by hair follicles regulates the trafficking of dendritic cells in skin. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(8):744–52. doi: 10.1038/ni.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ghigo C, Mondor I, Jorquera A, Nowak J, Wienert S, Zahner SP, Clausen BE, Luche H, Malissen B, Klauschen F, Bajénoff M. Multicolor fate mapping of Langerhans cell homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1657–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sieweke MH, Allen JE. Beyond stem cells: self-renewal of differentiated macrophages. Science. 2013;342(6161):1242974. doi: 10.1126/science.1242974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boulpaep EL. Blood. In: Boron WF, Boulpaep EL, editors. Medical physiology: a cellular and molecular approach. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 448–66. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia JA, Pino PA, Mizutani M, Cardona SM, Charo IF, Ransohoff RM, Forsthuber TG, Cardona AE. Regulation of adaptive immunity by the fractalkine receptor during autoimmune inflammation. J Immunol. 2013;191(3):1063–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henson PM, Bratton DL. Antiinflammatory effects of apoptotic cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(7):2773–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI69344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Litvack ML, Palaniyar N. Soluble innate immune pattern-recognizing proteins for clearing dying cells and cellular components: implications on exacerbating or resolving inflammation. Innate Immun. 2010;16(3):191–200. doi: 10.1177/1753425910369271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grimsley C, Ravichandran KS. Cues for apoptotic cell engulfment: eat-me, don’t eat-me and come-get-me signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(12):648–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Savage DC. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:107–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):762–74. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(4):902–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wong KL, Tai JJ, Wong WC, Han H, Sem X, Yeap WH, Kourilsky P, Wong SC. Gene expression profiling reveals the defining features of the classical, intermediate, and nonclassical human monocyte subsets. Blood. 2011;118(5):e16–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-326355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gibon E, Ma T, Ren PG, Fritton K, Biswal S, Yao Z, Smith L, Goodman SB. Selective inhibition of the MCP-1-CCR2 ligand-receptor axis decreases systemic trafficking of macrophages in the presence of UHMWPE particles. J Orthop Res. 2012;30(4):547–53. doi: 10.1002/jor.21548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wynn TA, Chawla A, Pollard JW. Macrophage biology in development, homeostasis and disease. Nature. 2013;496(7446):445–55. doi: 10.1038/nature12034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willert HG, Buchhorn GH, Fayyazi A, Flury R, Windler M, Köster G, Lohmann CH. Metal-on-metal bearings and hypersensitivity in patients with artificial hip joints. A clinical and histomorphological study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(1):28–36. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.A.02039pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317(5838):666–70. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurst SM, Wilkinson TS, McLoughlin RM, Jones S, Horiuchi S, Yamamoto N, Rose-John S, Fuller GM, Topley N, Jones SA. Il-6 and its soluble receptor orchestrate a temporal switch in the pattern of leukocyte recruitment seen during acute inflammation. Immunity. 2001;14(6):705–14. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marin V, Montero-Julian FA, Grès S, Boulay V, Bongrand P, Farnarier C, Kaplanski G. The IL-6-soluble IL-6Ralpha autocrine loop of endothelial activation as an intermediate between acute and chronic inflammation: An experimental model involving thrombin. J Immunol. 2001;167(6):3435–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma J, Chen T, Mandelin J, Ceponis A, Miller NE, Hukkanen M, Ma GF, Konttinen YT. Regulation of macrophage activation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60(11):2334–46. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3020-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kouri VP, Olkkonen J, Ainola M, Li TF, Björkman L, Konttinen YT, Mandelin J. Neutrophils produce interleukin-17B in rheumatoid synovial tissue. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2014;53(1):39–47. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ket309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(12):958–69. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dyken SJ, Locksley RM. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: roles in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:317–43. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677–86. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinez FO, Helming L, Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages: an immunologic functional perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:451–83. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hesse M, Modolell M, La Flamme AC, Schito M, Fuentes JM, Cheever AW, Pearce EJ, Wynn TA. Differential regulation of nitric oxide synthase-2 and arginase-1 by type 1/type 2 cytokines in vivo: Granulomatous pathology is shaped by the pattern of L-arginine metabolism. J Immunol. 2001;167(11):6533–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.11.6533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zizzo G, Cohen PL. IL-17 stimulates differentiation of human anti-inflammatory macrophages and phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophil in response to IL-10 and glucocorticoids. J Immunol. 2013;190(10):5237–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jämsen E, Kouri V-P, Olkkonen J, Coer A, Goodman SB, Konttinen YT, Pajarinen J. Characterization of macrophage polarizing cytokines in the aseptic loosening of total hip replacement. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(9):1241–46. doi: 10.1002/jor.22658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pajarinen J, Kouri VP, Jämsen E, Li TF, Mandelin J, Konttinen YT. The response of macrophages to titanium particles is determined by macrophage polarization. Acta Biomater. 2013;9(11):9229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20(2):86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jimi E, Nakamura I, Duong LT, Ikebe T, Takahashi N, Rodan GA, Suda T. Interleukin 1 induces multinucleation and bone-resorbing activity of osteoclasts in the absence of osteoblasts/stromal cells. Exp Cell Res. 1999;247(1):84–93. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komano Y, Nanki T, Hayashida K, Taniguchi K, Miyasaka N. Identification of a human peripheral blood monocyte subset that differentiates into osteoclasts. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8(5):R152. doi: 10.1186/ar2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiu YG, Shao T, Feng C, Mensah KA, Thullen M, Schwarz EM, Ritchlin CT. CD16 (FcRgammaIII) as a potential marker of osteoclast precursors in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12(1):R14. doi: 10.1186/ar2915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR, Kelley M, Chang MS, Luthy R, Nguyen HQ, Wooden S, Bennett L, Boone T, Shimamoto G, DeRose M, Elliott R, Colombero A, Tan HL, Trail G, Sullivan J, Davy E, Bucay N, Renshaw-Gegg L, Hughes TM, Hill D, Pattison W, Campbell P, Sander S, Van G, Tarpley J, Derby P, Lee R, Boyle WJ. Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell. 1997;89(2):309–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivollier A, Mazzorana M, Tebib J, Piperno M, Aitsiselmi T, Rabourdin-Combe C, Jurdic P, Servet-Delprat C. Immature dendritic cell transdifferentiation into osteoclasts: a novel pathway sustained by the rheumatoid arthritis microenvironment. Blood. 2004;104(13):4029–37. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu W, Zhang X, Zhang C, Tang T, Ren W, Dai K. Expansion of CD14+CD16+ peripheral monocytes among patients with aseptic loosening. Inflamm Res. 2009;58(9):561–70. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0020-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sallusto F, Cella M, Danieli C, Lanzavecchia A. Dendritic cells use macropinocytosis and the mannose receptor to concentrate macromolecules in the major histocompatibility complex class II compartment – downregulation by cytokines and bacterial products. J Exp Med. 1995;182(2):389–400. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Randolph GJ, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science. 1998;282(5388):480–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Randolph GJ, Inaba K, Robbiani DF, Steinman RM, Muller WA. Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity. 1999;11(6):753–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Randolph GJ, Sanchez-Schmitz G, Liebman RM, Schäkel K. The CD16(+) (FcgammaRIII(+)) subset of human monocytes preferentially becomes migratory dendritic cells in a model tissue setting. J Exp Med. 2002;196(4):517–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bullwinkel J, Lüdemann A, Debarry J, Singh PB. Epigenotype switching at the CD14 and CD209 genes during differentiation of human monocytes to dendritic cells. Epigenetics. 2011;6(1):45–51. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.1.13314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Collin M, McGovern N, Haniffa M. Human dendritic cell subsets. Immunology. 2013;140(1):22–30. doi: 10.1111/imm.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Segura E, Touzot M, Bohineust A, Cappuccio A, Chiocchia G, Hosmalin A, Dalod M, Soumelis V, Amigorena S. Human inflammatory dendritic cells induce Th17 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2013;38(2):336–48. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inaba K, Pack M, Inaba M, Sakuta H, Isdell F, Steinman RM. High levels of a major histocompatibility complex II self peptide complex on dendritic cells from the T cell areas of lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 1997;186(5):665–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cobelli N, Scharf B, Crisi GM, Hardin J, Santambrogio L. Mediators of the inflammatory response to joint replacement devices. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(10):600–8. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maitra R, Clement CC, Scharf B, Crisi GM, Chitta S, Paget D, Purdue PE, Cobelli N, Santambrogio L. Endosomal damage and TLR2 mediated inflammasome activation by alkane particles in the generation of aseptic osteolysis. Mol Immunol. 2009;47(2–3):175–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Cement disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;225:192–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris WH. Osteolysis and particle disease in hip replacement. A review. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994;65(1):113–23. doi: 10.3109/17453679408993734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gallo J, Kamínek P, Tichá V, Riháková P, Ditmar R. Particle disease. A comprehensive theory of periprosthetic osteolysis: a review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2002;146(2):21–8. doi: 10.5507/bp.2002.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Greenfield EM, Bi Y, Ragab AA, Goldberg VM, Nalepka JL, Seabold JM. Does endotoxin contribute to aseptic loosening of orthopedic implants? J Biomed Mater Res B. 2005;72(1):179–85. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hoenders CS, Harmsen MC, van Luyn MJ. The local inflammatory environment and microorganisms in “aseptic” loosening of hip prostheses. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2008;86(1):291–301. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pussinen PJ, Vilkuna-Rautiainen T, Alfthan G, Palosuo T, Jauhiainen M, Sundvall J, Vesanen M, Mattila K, Asikainen S. Severe periodontitis enhances macrophage activation via increased serum lipopolysaccharide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24(11):2174–80. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145979.82184.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Konttinen YT, Sillat T, Barreto G, Ainola M, Nordström DC. Osteoarthritis as an autoinflammatory disease caused by chondrocyte-mediated inflammatory responses. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(3):613–6. doi: 10.1002/art.33451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schmalzried TP, Jasty M, Harris WH. Periprosthetic bone loss in total hip arthroplasty. Polyethylene wear debris and the concept of the effective joint space. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(6):849–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Virtanen S, Milosev I, Gomez-Barrena E, Trebse R, Salo J, Konttinen YT. Special modes of corrosion under physiological and simulated physiological conditions. Acta Biomater. 2008;4(3):468–76. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Konttinen YT, Milošev I, Trebše R, van der Linden R, Pieper J, Sillat T, Virtanen S, Tiainen VM. Metals for joint replacement. In: Revell P, editor. Joint replacement technology Cambridge. 2. England: Woodhead Publishing; 2014. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gamerdinger K, Moulon C, Karp DR, Van Bergen J, Koning F, Wild D, Pflugfelder U, Weltzien HU. A new type of metal recognition by human T cells: contact residues for peptide-independent bridging of T cell receptor and major histocompatibility complex by nickel. J Exp Med. 2003;197(10):1345–53. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schmidt M, Raghavan B, Müller V, Vogl T, Fejer G, Tchaptchet S, Keck S, Kalis C, Nielsen PJ, Galanos C, Roth J, Skerra A, Martin SF, Freudenberg MA, Goebeler M. Crucial role for human Toll-like receptor 4 in the development of contact allergy to nickel. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(9):814–9. doi: 10.1038/ni.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tyson-Capper AJ, Lawrence H, Holland JP, Deehan DJ, Kirby JA. Metal-on-metal hips: cobalt can induce an endotoxin-like response. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(3):460–1. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rachmawati D, Bontkes HJ, Verstege MI, Muris J, von Blomberg BM, Scheper RJ, van Hoogstraten IM. Transition metal sensing by Toll-like receptor-4: next to nickel, cobalt and palladium are potent human dendritic cell stimulators. Contact Dermatitis. 2013;68(6):331–8. doi: 10.1111/cod.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Raghavan B, Martin SF, Esser PR, Goebeler M, Schmidt M. Metal allergens nickel and cobalt facilitate TLR4 homodimerization independently of MD2. EMBO Rep. 2012;13(12):1109–15. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]