Abstract

Research on affect and self-esteem in social anxiety disorder (SAD) has focused on trait or average levels, but we know little about the dynamic patterns of these experiences in the daily lives of people with SAD. We asked 40 adults with SAD and 39 matched healthy controls to provide end-of-day reports on their affect and self-esteem over two weeks. Compared to healthy adults, participants with SAD exhibited greater instability of negative affect and self-esteem, though the self-esteem effect was driven by mean level differences. The SAD group also demonstrated a higher probability of acute changes in negative affect and self-esteem (i.e., from one assessment period to the next), as well as difficulty maintaining positive states and improving negative states (i.e., dysfunctional self-regulation). Our findings provide insights on the phenomenology of SAD, with particular attention to the temporal dependency, magnitude of change, and directional patterns of psychological experiences in everyday life.

Keywords: social anxiety, emotion, self-esteem, emotional control, individual differences

People with generalized social anxiety disorder (SAD) experience significant impairment in quality of life and, specifically, in the social domain (Wittchen & Beloch, 1996). This condition is marked by pervasive fears of being evaluated by others and avoidance of social situations that may lead to scrutiny or rejection (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Ample research has shown that people with SAD experience elevated levels of negative affect (NA; e.g., Watson, Clark, & Carey, 1988), attenuated positive affect (PA; Kashdan, 2007), and low self-esteem (SE; e.g., Leary, Kowalski, & Campbell, 1988), but we know little about the quality and patterns of affective and SE fluctuations in their daily lives. In the current study, we investigated whether affective or SE instability plays a role in the phenomenology of SAD.

All people experience some variability in their affect and self-esteem, as fluctuations in emotions (Keltner & Kring, 1998) and self-esteem (Leary & Downs, 1995) are integral to effectively navigating social relationships. For example, a decrease in self-esteem alerts us to the likelihood that we might make a negative impression on others, which could lead to rejection (Leary, Haupt, Strausser, & Chokel, 1998). However, some people are prone to affective instability (frequent and/or severe shifts in affect) or self-esteem instability (frequent and/or severe shifts in self-views). Excessive fluctuation in self-esteem may represent dysfunction in mechanisms aimed at maintaining a degree of stability in these psychological states (e.g., Carver & Scheier, 2001; Tesser, 1988). Examining the temporal patterns of psychological states in SAD may provide crucial information about underlying regulatory functioning in this condition.

Since frequent, unpredictable emotional changes tend to be distressing (Craske, Brown, Meadows, & Barlow, 1995), it is not surprising that people with affective instability are at greater risk for developing disorders (Koenigsberg, 2010). Excessive affective instability has been found in patients with borderline personality disorder (e.g., Ebner-Priemer et al., 2007), major depressive disorder (e.g., Thompson et al., 2012), and bulimia nervosa (Anestis et al., 2010). The deleterious effects of instability are not limited to NA fluctuations. Instability of PA has been linked to psychological symptoms (e.g., Gruber, Kogan, Quoidbach, & Mauss, 2013). Only two studies have investigated mood instability in anxiety disorders using experience-sampling methodology (ESM; Larson & Csikszentmihalyi, 1983), each suggesting that patients with anxiety disorders experience greater NA instability (Bowen, Baetz, Hawkes, & Bowen, 2006; Bowen, Clark, & Baetz, 2004). However, these studies made no comparisons between anxiety disorder diagnoses, used one-item affect scales, and failed to address mean affect ratings as a covariate (see Kashdan, Uswatte, Steger, & Julian, 2006).

For people with generalized SAD, affective instability might be particularly important, because their source of intense distress (i.e., social interaction) is ubiquitous in daily life. The affective profile of SAD is distinct from other anxiety disorders, with amplified levels of NA accompanied by deficient PA (e.g., T. A. Brown, 2007; Hughes et al., 2006) that cannot be attributed to comorbidity with depressive disorders (Kashdan, 2007). Notably, ESM studies (e.g., Kashdan, Julian, Merritt, & Uswatte, 2006; Kashdan & Steger, 2006) that support these global self-report findings have used samples with analogue problems instead of SAD diagnoses. To date, researchers have ignored instability, which may clarify whether PA deficits reflect consistently dampened PA experiences (PA generally low, with little improvement) or greater PA instability (high PA but short lived and infrequent). In the present study, we investigated the level and stability of PA and NA in healthy adults and those with SAD diagnoses.

Dominant models of SAD highlight the role of emotional reactivity, in part due to biased processing of social situations (Clark & Wells, 1995; Rapee & Heimberg, 1997). Consequently, we expected the SAD group to display greater NA instability in daily life. Considering prior studies that found no differences in PA instability in anxiety disorders (e.g., Bowen et al., 2006) and stable, low PA levels over three months in socially anxious people (Kashdan & Breen, 2008), we expected no group differences in PA instability. In analyses controlling for average levels of affect, we addressed the parsimonious explanation that any effects might be a function of stable emotional disturbances.

Although no studies to date have used ESM to study self-esteem experiences in people with SAD over time, several dominant models of SAD (Clark & Wells, 1995; Moscovitch, 2009) describe the role of low and, specifically, unstable self-esteem in the phenomenology of SAD. In particular, Clark and Wells (1995) suggested that instability of self-esteem might distinguish SAD from the stable, low self-esteem in people with depression. Related research provides preliminary evidence that self-esteem instability is worthy of investigation in people with SAD. First, on global and implicit measures, socially anxious people tend to have less-certain self-concepts, i.e., they report being less confident in and take longer in describing their personality traits (Stopa, Brown, Luke, & Hirsch, 2010; Wilson & Rapee, 2006). Second, ESM research has shown that high self-esteem variability predicted greater focus on threatening aspects of social interactions (Waschull & Kernis, 1996), greater social anxiety (Kernis, Grannemann, & Barclay, 1992), more social avoidance, and fewer social interaction (Oosterwegel, Field, Hart, & Anderson, 2001)—all features commonly seen in patients with SAD (Leary et al., 1988).

In addition to studying instability, researchers can examine the quality of changes in reported experiences, particularly their amplitude and direction. The likelihood of acute changes in affect (i.e., large shifts in amplitude from one occasion to the next) and the patterns of direction of shifts (i.e., shifting toward more positive or more negative valence) have been of particular interest to researchers studying borderline personality disorder (e.g., Ebner-Priemer et al., 2007; Trull et al., 2008). Little consideration has been given to acute changes and directional shifts in other psychological disorders. Based on theories of hyper-reactivity and emotion regulation deficits in SAD, we expected to find a higher probability of acute changes in NA and self-esteem (but not PA), and a dysfunctional pattern of affect shifts in participants with SAD.

Although affect changes from positive to negative states tend to be distressing (Craske et al., 1995), the ability to shift from negative states to positive states may be a sign of effective emotion regulation. A growing body of literature supports emotion regulation difficulties as a feature and possible maintenance factor of SAD (e.g., Goldin, Manber, Hakimi, Canli, & Gross, 2009; Kashdan & Steger, 2006). In particular, people with SAD tend to overuse the emotion regulation strategies of avoidance and suppression, which tend to be ineffective for altering negative emotions (Campbell-Sills, Barlow, Brown, & Hofmann, 2006) and contribute to deficits in positive experiences (Farmer & Kashdan, 2012; Kashdan & Steger, 2006). Rigid reliance on pushing emotions away and having difficulty using more adaptive strategies (e.g., Werner, Goldin, Ball, Heimberg, & Gross, 2011) suggest that people with SAD may have difficulty reducing negative affect. Consequently, we expected participants with SAD to experience smaller positive shifts (i.e., toward more positive valence) when in negatively valenced states.

People with SAD may also have a harder time maintaining high PA states. Prior research found that socially anxious people tend to suppress positive emotions more frequently in daily life than less anxious peers (Farmer & Kashdan, 2012). This strategy is in conflict with more adaptive emotion regulation strategies that intensify and prolong positive experiences (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2006). Thus, people with SAD may more rapidly shift to relatively negative affect states after the rare days on which they experience predominantly positive valence. Consistent with this idea, we expected SAD participants to experience more negative shifts (i.e., toward more negative valence) after being in positively valenced states. Understanding emotional dysregulation patterns in the daily lives of people with SAD may offer insights into the source of functional impairment in this population.

In the present investigation, we used a two-week daily diary ESM to examine affective and self-esteem instability in people with generalized SAD compared to healthy adults. To capture instability, a measure must incorporate the amplitude, frequency, and temporal dependency of changes in experiences over time (Larsen, 1987). One such measure is the mean squared successive differences (MSSD; von Neumann, Kent, Bellinson, & Hart, 1941), calculated by aggregating the degree of fluctuation between each time point and the time point immediately preceding it. Variations of this approach that further improve the measurement include correcting for missing data and varying durations between assessments (Jahng, Wood, & Trull, 2008). MSSD and its variations have been applied to the study of affective instability in a number of clinical populations for which labile affect has been theoretically or clinically problematic (e.g., Anestis et al., 2010; Bowen et al., 2006).

In the present study, we used a two-week daily diary ESM to investigate the temporal dynamics of affect and self-esteem in people with generalized SAD compared to healthy adults. We hypothesized that the SAD group would experience (a) lower mean levels of PA and self-esteem, and higher mean levels of NA; (b) greater NA and self-esteem instability, but no differences in PA instability; (c) higher probability of acute changes in NA and self-esteem, but not PA; and (d) more negative shifts from positively valenced affect and less positive shifts from more negatively valenced affect. To test specificity, we examined whether group differences remained after accounting for differences in mean intensity levels and the presence of comorbid depressive and anxiety conditions. Additionally, we explored the relationship of instability measures with each other and with global measures of symptom severity and well-being.

Method

Participants

Our sample included 86 adults (53 females) from the Northern Virginia community, of whom 43 participants were diagnosed with social anxiety disorder (SAD), generalized subtype, and 43 (50.0%) were a healthy control (HC) group with no psychiatric disorders. All participants spoke English fluently and were familiar with computers. Participants with SAD were excluded from the study if they presented with psychotic symptoms or substance misuse, but other comorbid disorders were allowed. We excluded seven participants from analyses because they did not provide at least three daily diary entries after the initial screening. This led to a final sample of 40 participants with generalized SAD diagnoses (25 women) and 39 HC participants (26 women), with an average age of 28.86 (SD = 8.76). Of our sample, 54.4% identified themselves as Caucasian/White, 19.0% as African American/Black, 12.7% as Hispanic/Latino, 5.1% as Asian/Asian-American, and 8.9% as “Other”. As for relationship status, 62.1% of the sample was single, 16.1% was married, 11.5% was cohabitating, 4.6% was divorced or separated, and 4.6% listed another relationship status. As for education level, 6.8% of our sample had completed high school or less, 32.2% had finished some college, 6.8% completed an Associate’s degree or professional school, 31% held a Bachelor’s degree, and 8% had completed at least some graduate study. Groups did not differ in age, t(77) = 0.52, p = .60, d = 0.12, gender, χ2(1) = 0.15, p = .70, d = 0.09, ethnicity, χ2(4) = 2.73, p = .60, relationship status, χ2(4) = 5.23, p = .27, or education, χ2(4) = 3.09, p = .54. Notably, one participant in the HC group did not respond to questions on relationship or education status.

We evaluated participants for the presence of comorbid Axis I psychological conditions using a clinical interview (described below). In the SAD group, 18 people met criteria for a comorbid anxiety disorder (ANX, 45%). Specifically, 11 qualified for a specific phobia, six for post-traumatic stress disorder, three for generalized anxiety disorder, two for obsessive-compulsive disorder, and one person for a panic disorder diagnosis. In addition, seven people in the SAD group met criteria for a current major depressive disorder episode or dysthymic disorder (DEP, 17.5%), and one participant met criteria for bipolar disorder. Notably, 42.5% of the SAD group had no comorbid diagnoses, and 25% were taking prescribed psychotropic medications. Treatment (binary coded for presence/absence) was not significantly related to any of the instability or compliance measures (all ps > .35). The average age of SAD onset was 12.46 years (SD = 4.22).

Procedure

We recruited potential participants using online advertisements and flyers (e.g., on bulletin boards) in the community urging interested persons to call our laboratory for information. Following a brief verbal informed consent procedure, trained research assistants conducted a structured phone screen with potential participants, assessing for social anxiety, generalized anxiety, depression symptoms, functional impairment, suicidality, and psychotic symptoms. If participants endorsed suicidal ideation, we provided referrals to local providers or emergency services as needed. If potential participants showed evidence of social anxiety fears that extended beyond public speaking situations (or endorsed no psychological symptoms for the healthy control group), the research assistant scheduled them for an initial assessment.

During the initial face-to-face session (conducted with 122 potential participants), participants provided informed consent and completed self-report questionnaires, including demographic questions and trait measures. Doctoral-level students in clinical psychology assessed for anxiety, mood, substance use, eating, and psychotic disorders with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002). In addition, the SCID was supplemented with the SAD module of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM–IV: Lifetime Version (Di Nardo, Brown, & Barlow, 1994). To be eligible for the generalized SAD group, participants had to endorse more than two feared social situations (beyond performance settings) and this condition had to be the primary or most severe diagnosis if other comorbid psychiatric conditions were present. To ensure inter-rater reliability for SAD diagnoses, 45 randomly chosen recorded interviews were rated by multiple researchers, resulting in excellent agreement (Cohen’s κ = .87).

Participants who qualified for the study received a 1.5-hr introductory session on the full protocol, which included practice with the self-initiated recording of daily social interactions, random prompts, and end-of-day records. The only data used in the present study were from the end-of-day records, for which participants were provided a de-identified code for making online daily diary entries each evening for the following 14 days. We chose 14 days as a time long enough to capture variability in daily life (i.e., by encapsulating every day of the week twice) without burdening participants. Participants were instructed to complete each daily entry between 6:00 P.M. on the day in question up to 11:59 A.M. of the following day to minimize memory bias. We excluded entries provided outside this period from analyses.

Two days into the experience-sampling data collection, we contacted participants to answer questions or troubleshoot any problems with logging into the questionnaire server or completing entries. Following this contact, researchers sent multiple reminder e-mails each week that emphasized compliance, confidentiality, and data coding details (i.e., time-and-date stamped entries). We also used an incentive structure to maximize compliance, such that participants received a minimum payment of $165 and could earn up to $50 in bonus money (50¢ for each completed end-of-day record and random prompt response, and $10 bonus for each uninterrupted week of reports). Prior research has used similar procedures to minimize missing data (e.g., Bardone, Krahn, Goodman, & Searles, 2000). Moreover, experience-sampling measures were kept brief to maintain participant motivation and maximize responses without sacrificing reliability or validity (Nezlek, 2012). At the end of the data collection, participants were debriefed, asking about any problems with data entry or data inaccuracies.

Person-Level Measures

Social anxiety

The 20-item Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, 1998) measured tendencies to fear and avoid social interactions due to concerns about being scrutinized by other people. Participants responded to statements using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all characteristic of me) to 4 (extremely characteristic of me), with higher scores on this scale representing greater social anxiety. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity across clinical, community, and student samples (E. J. Brown et al., 1997; Heimberg, Mueller, Holt, Hope, & Liebowitz, 1993; Mattick & Clarke, 1998). Notably, removing the three reverse scored items has been shown to slightly improve reliability and validity in prior work (Rodebaugh et al., 2011; Rodebaugh, Woods, & Heimberg, 2007). Thus, we used the 17-item SIAS-Straightforward (SIAS-S) scores for subsequent analyses for a more reliable and valid measure. Notably, in our study, the 17- and 20-item versions had identical internal consistency (α = .97) and correlated at .99, p < .001.

Depression

We assessed for the severity of depressive symptoms using the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory–Second Edition (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996). Participants responded to items on a scale from 0 to 3 to describe their experiences over the prior 2-week period, such that higher scores represented greater depressive symptoms. In prior research, this measure has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity, including the ability to differentiate people with and without mood disorder diagnoses (Beck et al., 1996; Sprinkle et al., 2002). Our sample had acceptable internal reliability (α = .93).

Daily Measures

Daily affect

Each evening, participants described their affective experience on that particular day with 12 items. Using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very slightly/not at all) to 5 (extremely), participants rated how much the following adjectives described them “today”. Negative affect items were anxious, angry, sluggish, sad, irritable, and distressed. Positive affect items were content, relaxed, enthusiastic, joyful, proud, and interested. These adjectives reflect items from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1994) that sample both high and low energy emotions in the circumplex model of emotions (Barrett, 1998); similar items have been used in prior experience sampling research (e.g., Nezlek & Kuppens, 2008). We calculated reliability of the scales by creating a series of three-level unconditional models with items nested within days, and days nested within people (Nezlek, 2007). In these analyses, the reliability of the Level 1 intercept is functionally equivalent to a Cronbach’s alpha, adjusted for differences between days and people. Given that reliability was acceptable for positive (α = .89) and negative (α = .81) affect items, these were averaged for each day to create positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) daily scores.

Daily Self-Esteem

We assessed participants’ self-esteem on the day in question with a 2-item measure. On a 7-point scale from 1 (very uncharacteristic of me today) to 7 (very characteristic of me today), participants responded to two items: “I felt I had good qualities” and “I felt satisfied with myself”. This scale has been used in prior experience-sampling research (e.g., Kashdan, Weeks, & Savostyanova, 2011), and our sample demonstrated acceptable reliability (α = .90), calculated as described above. We averaged items to create a daily self-esteem score for each end-of-day entry.

Data Analysis

Given that our daily diary data involved multiple assessments over many days, not all participants provided an equal number of entries across the assessment period. To account for the unbalanced data contributions of each participant, we used multilevel modeling to estimate mean levels of affect and self-esteem, as well as to investigate group differences in variability, instability, and affect changes. We set the statistical significance level of the p-value to .05, adjusted with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons to minimize Type I error (Ludbrook, 1998).

Mean levels

First, we examined group differences in PA, NA, and self-esteem using two-level models with each measurement for each participant (at Level 1) as the outcome, predicted by SAD diagnostic status (at Level 2).

Instability1

We investigated instability by calculating the fluctuations of affect and self-esteem over time using squared successive differences (SSDs). Similar to the mean squared successive differences (MSSD) statistic suggested by Jahng and colleagues (2008), we computed the difference from each measurement to the next (squared, so that larger changes are weighted more). Given the possible influence of missing data inflating changes, we divided SSDs by the number of days elapsed since the prior measurement. Notably, our results were similar with and without this time adjustment. Given that participants contributed different numbers of entries to the calculation of the instability, and given that SSD scores follow a gamma distribution, we estimated MSSDs using generalized multilevel modeling with log link. In these two-level models, adjusted SSDs were modeled as outcomes predicted by SAD diagnostic group at Level 2. Covariates (e.g., mean levels, gender, comorbid diagnoses) were added to the models to test for specificity of results. Although there are currently no accepted guidelines for reporting effect sizes in multilevel models, we reported Cohen’s d values derived from t-ratios and degrees of freedom for an estimate of the magnitude of our effects (Rosenthal, Rosnow, & Rubin, 2000). Cohen (1988) defined medium effect sizes at d = .5 and large effect sizes at d = .8.

Acute changes

We sought to investigate whether people with SAD experience more frequent extreme affect or self-esteem shifts. Following Trull et al. (2008), we characterized acute changes as those that equaled or exceeded the value for the 90th percentile of SSDs (defined as above) across all participants in the study2. We then used logistic (binomial) multilevel models to compare the probability of acute changes between diagnostic groups. Acute changes at each measurement occasion (1 = occurred, 0 = not occurred) were modeled as the outcome at Level 1, with SAD diagnostic group as a Level 2 predictor. Similarly, covariates were added to the models to test for specificity.

Affect shift patterns

To understand the direction of affective shifts, we computed a single index of affect valence to capture the continuum of affective experiences from negative to positive by subtracting the NA score from the PA score for each data point (resulting in a range of −4 to 4). Researchers have used this aggregating method to account for the inverse correlation between PA and NA over the course of brief time intervals (Green, Salovey, & Truax, 1999). PA and NA correlated at -.829 (p < .001) in our sample. Given the high collinearity between valence and PA (r = .942, p < .001, d = 5.61), and between valence and NA (r = -.854, p < .001, d = 3.28), we used this index only to test hypotheses regarding affect shifts on the positive to negative affect continuum.

We calculated successive differences of valence (adjusted for time as above but not squared to preserve direction) and categorized each change based on the affect valence of its initial time point. Specifically, if the initial measurement in the shift was positive (i.e., PA – NA > 0 on that occasion), the shift was grouped with other shifts from positive valence, and if the initial measurement was negatively valenced (i.e., PA – NA ≤ 0), it was grouped with other shifts from negative valence. Effectively, we separately characterized the magnitude and direction of changes participants experienced from days they had primarily positive (or negative) affect. Notably, participants had unequal numbers of days contributing to these categories (38 HC vs. 39 SAD for positive, but 11 HC vs. 36 SAD for negative). Thus, we compared groups using multilevel modeling, which is robust for unbalanced observations across participants, since it allows relative contribution of each participant to vary. In these models, changes for each category were modeled as outcomes, with SAD diagnostic group included as a Level 2 predictor. As previously, covariates were added to the models in tests of specificity.

Associations of instability with well-being

To address the phenomenology of unstable affect and self-esteem, we analyzed relationships of the estimated MSSD variables (estimated intercepts from multilevel analyses) with each other and with person-level measures. To explore whether instability measures predict global levels of social anxiety or depression, we used hierarchical linear regressions, where we controlled for mean levels in the first step, then added instability in the second step, and then a Mean Level × Instability effect. Predictors were standardized prior to creating interaction terms.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Overall, our sample demonstrated good compliance. During the experience-sampling data collection, participants provided an average of 12.19 end-of-day entries (SD = 3.67), for a total of 963 days of data. There were no differences between the SAD and control groups in the number of days reported (t = 0.92, SE = 0.83, p = .92, Cohen’s d = 0.09). Not surprisingly, SAD and control groups significantly differed on the person-level measures, with higher scores on the SIAS-S (d = 4.74) and BDI (d = 1.72). Table 1 lists the descriptive statistics of the measures by group. Notably, the means for our SAD group on the SIAS-S were commensurate with average scores of clients in treatment for SAD (M = 43.93, SD = 11.84) and substantially higher than scores of community samples of adults (M = 16.30, SD = 12.48; Rodebaugh et al., 2011).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Between Group Differences for Daily Affect and Self-Esteem

| Group differences |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | SAD groupa | HC groupb | β | t-ratio | p-value |

| SIAS-S | 43.57 (8.86) | 8.09 (5.99) | 0.91 | 20.80 | < .001 |

| BDI-II | 17.00 (10.88) | 3.15 (3.60) | 0.65 | 7.55 | < .001 |

| Mean Valence | 0.36 (0.15) | 1.87 (0.13) | −0.76 | −7.80 | < .001 |

| Mean PA | 2.33 (0.10) | 3.29 (0.09) | −0.48 | −7.11 | < .001 |

| Mean NA | 1.97 (0.07) | 1.42 (0.06) | 0.28 | 6.01 | < .001 |

| Mean SEc | 4.00 (0.21) | 5.43 (0.13) | −0.72 | −5.83 | < .001 |

| PA acute changes | 0.16 (0.06) | 0.12 (0.06) | 0.13 | 0.95 | .347 |

| NA acute changes | 0.17 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.55 | 3.21 | .002 |

| SE acute changesc | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.48 | 3.06 | .004 |

Notes. Tabulated data depict means (with standard deviations) for self-report measures, and estimated group means (with standard errors) for experience sampling data derived from multilevel models. Acute changes reflect probabilities of shifts ≥ 90th percentile in magnitude. SAD = social anxiety disorder; HC = healthy control; SIAS-S = Social Interaction Anxiety Scale-Straightforward; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; PA = positive affect; NA = negative affect; SE = self-esteem.

n = 40.

n = 39.

Statistics based on 78 participants due to missing data.

Do People with SAD Differ in Mean Level or Variability of Daily Experiences?

Consistent with our first hypothesis (a), the SAD group had lower levels of daily PA and self-esteem, and higher levels of daily NA on average. Group status explained 30.7%, 40.1%, and 34.1% in between-person variance (R2) in PA, NA, and self-esteem, respectively (ds = 1.62, 1.37, and 1.34, respectively). Additionally, the SAD group had lower average levels of affect valence, with group status explaining 45.6% of variance in valence (d = 1.78). Table 1 lists the estimated means by group.

Do People with SAD Have More Unstable Daily Experiences?

Since variability does not capture the frequency or extremity of fluctuations, we computed SSDs of PA, NA, and self-esteem ratings, as described above. Consistent with hypotheses (b), SAD diagnosis predicted significantly more unstable NA (R2 = .15, d = 0.66) and self-esteem (R2 = .12, d = 0.93), but not PA (R2 = .02, d = 0.28) without any covariates. We then tested whether these differences were significant when controlling for mean levels (age and gender were entered as covariates initially and removed if not significant). Table 2 describes multilevel analyses of group differences in SSDs.

Table 2.

Multilevel Models Predicting the Instability of Daily Affect and Self-Esteem

| Outcome | df | β | SE | t-ratio | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily PA SSD | |||||

| Intercept | 1, 77 | −0.67 | 0.10 | −6.86 | < .001 |

| SAD | 0.12 | 0.10 | 1.24 | .221 | |

| Intercept | 4,74 | −0.73 | 0.08 | −8.67 | < .001 |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −3.72 | .001 | |

| SAD | 0.11 | 0.13 | 0.86 | .391 | |

| Mean PA | −0.01 | 0.12 | −0.07 | .949 | |

| SAD × Mean PA | 0.35 | 0.12 | 3.00 | .004 | |

| Daily NA SSD | |||||

| Intercept | 1, 77 | −0.85 | 0.14 | −6.27 | < .001 |

| SAD | 0.40 | 0.14 | 2.91 | .005 | |

| Intercept | 3, 75 | −1.20 | 0.08 | −15.44 | < .001 |

| SAD | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.65 | .516 | |

| Mean NA | 1.00 | 0.08 | 12.03 | < .001 | |

| SAD × Mean NA | −0.38 | 0.08 | −4.63 | < .001 | |

| Daily Self-Esteem SSD | |||||

| Intercept | 1, 76 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 5.40 | < .001 |

| SAD | 0.36 | 0.09 | 4.03 | < .001 | |

| Intercept | 3, 74 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 4.90 | < .001 |

| SAD | 0.13 | 0.10 | 1.37 | .174 | |

| Mean Self-Esteem | −0.49 | 0.13 | −3.71 | .001 | |

| SAD × Mean Self-Esteem | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.76 | .083 |

Notes.Group differences were tested by generalized linear models with log link. Only diagnostic group contrast was entered in first models for each construct. Gender, age, group contrast, mean levels, and interaction of group and mean level were initially entered in the second models; gender and/or age were removed if non-significant. NA = negative affect; PA = positive affect; SAD = Social Anxiety Disorder Diagnosis (contrast coded); SSD = squared successive differences.

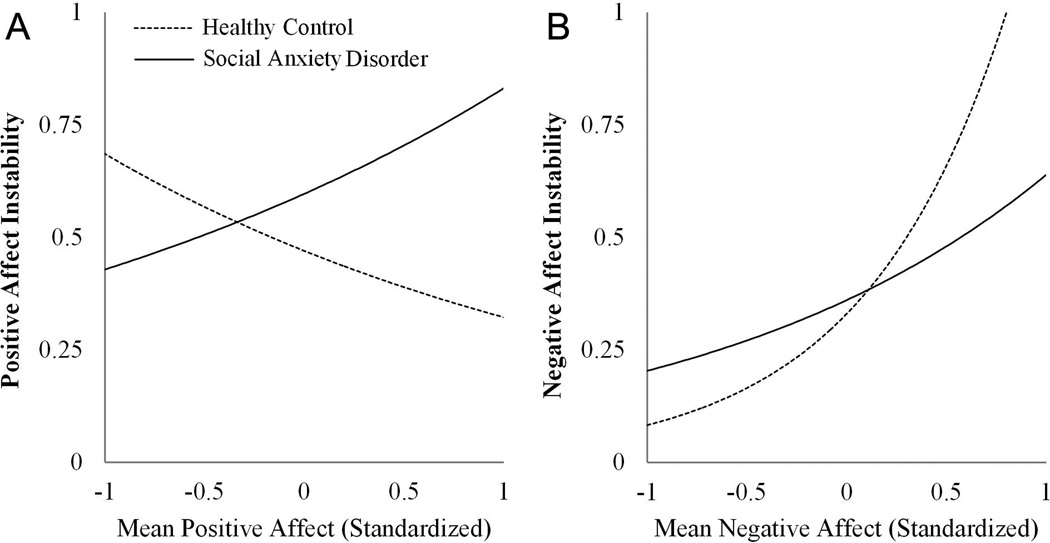

We found a significant SAD × Mean PA interaction (d = 0.70) in predicting PA instability; we probed this effect by computing parameter estimates separately by group and plotting exponentiated function values for each group (Ai & Norton, 2003). Figure 1 (a) demonstrates that higher mean PA predicted greater PA instability for people with SAD (b = .35, p = .009) but slightly less PA instability for controls (b = -.43, p = .055). This result suggests that, among people with SAD, those who experienced more PA on average displayed greater PA fluctuation (i.e., intermittent high PA days), while among controls, those with higher mean PA tended to have more stable PA experiences. Age was also a significant predictor, such that older participants displayed more stable PA (d = 0.70). SAD (d = 0.20) and mean PA (d = 0.02) were not significant main effects in this final model, which altogether explained 21.2% of between-person variance in PA instability.

Figure 1. Effect of Diagnostic Group × Mean Daily Affect on Affective Instability.

Notes. These graphs demonstrate the differential effect of mean affect level on affect instability (squared successive deviations) for people with and without social anxiety disorder based on the fitted values from multilevel models. The x-axes represent the standardized mean levels (shown from −1 SD to +1 SD) for negative affect (a) and positive affect (b). All individual effects are significantly different from zero (p < .05).

When we included mean intensity of daily NA as a covariate in predicting NA instability, we also found a significant interaction effect of SAD × Mean NA (d = 1.07). Figure 1 (b) demonstrates that people who experienced higher mean levels of NA tended to have more unstable NA, but controls demonstrated a steeper effect (b = 1.32, p < .001) than the SAD group (b = .62, p < .001). Mean NA (d = 2.78), but not SAD (d = 0.15), also had a significant main effect. The full model explained 67.5% of between person variance in NA instability.

When including average self-esteem levels as a covariate in predicting self-esteem instability, SAD was no longer significant (d = 0.32). A main effect of mean self-esteem was significant (d = 0.86), suggesting that people with higher self-esteem had more stable self-esteem. Additionally, there was a marginal nonsignificant SAD x Mean Self-Esteem interaction (d = 0.41, p = .083, uncorrected). Tentative decomposition of the effect suggested that healthy controls had a stronger negative relationship of mean level and instability (b = −0.72, p = .007) than SAD participants (b = −.25, p = .023). The final model explained 22% of the between-person variance in self-esteem instability. Overall, these results suggest that people with SAD have more unstable SE, but this difference is a function of having lower self-esteem levels.

Are These Differences Due to Comorbid Conditions?

To address the possibility that SAD instability findings3 may be due to comorbid conditions, we ran additional analyses including binary variables for comorbid depression disorders (DEP; 1 = present, 0 = absent) and comorbid anxiety disorders (ANX; 1 = present, 0 = absent). The SAD x Mean Level interactions remained significant for NA instability (d = 0.90, p < .001) and PA instability (d = 0.60, p = .014). Notably, DEP significantly predicted more stable NA (β = −.83, SE = .23, p = .001, d = 0.85) but not PA (β = −.42, SE = .26, p = .11, d = 0.38). ANX did not significantly predict PA instability (β = .34, SE = .22, p = .13, d = 0.36) or NA instability (β = .33, SE = 0.23, p = .16, d = 0.33). Models with comorbid diagnoses explained an additional 18.5% and 2.9% of between-person variance in NA and PA instability, respectively.

Do People with SAD Experience More Acute Shifts in Daily Experiences?

Consistent with our hypothesis (c), SAD participants experienced more extreme shifts (magnitude > 90th percentile) in NA and self-esteem, but not PA. Table 1 lists estimated mean probabilities and group differences in experiencing acute shifts. Specifically, SAD predicted a greater likelihood of acute changes in NA (R2 = .13, d = 0.73) and self-esteem (R2 = .12, d = 0.70), but not PA (R2 = .01, d = 0.22). These differences remained significant (ps < .01, ds > 0.6) in follow-up tests controlling for comorbid diagnoses. ANX was marginally predictive of more likely acute changes in PA (β = .65, SE = .34, p = .061, d = 0.43), and no other covariates were significant (ps > .5). Additionally, models with comorbid diagnoses explained no additional variance (0%).

Do People with SAD Display Different Patterns of Affect Changes?

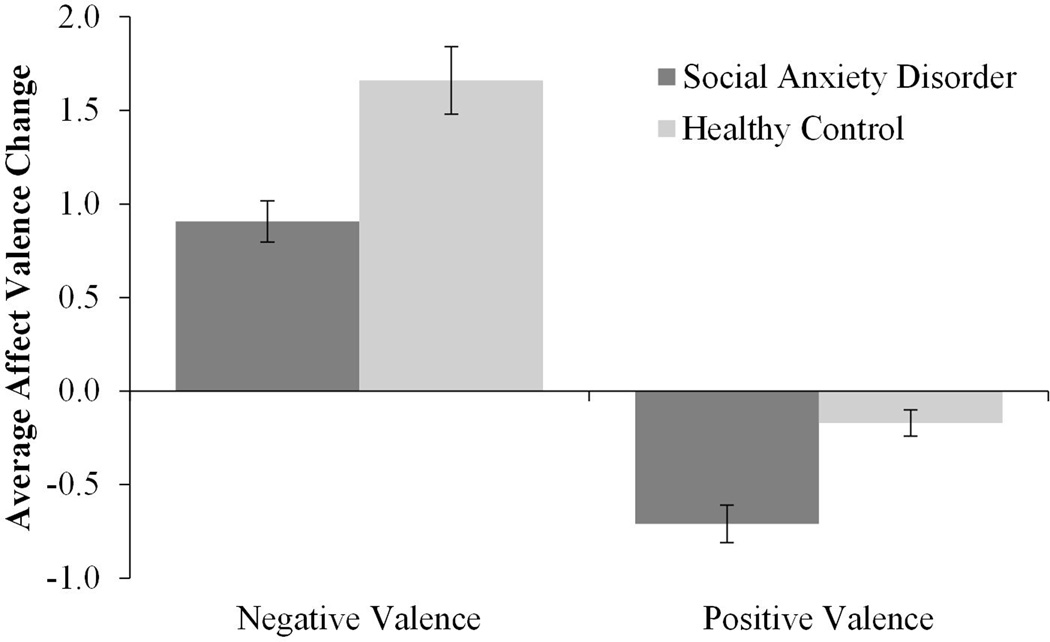

Consistent with our hypothesis, we found a dysfunctional directional pattern of affect changes in participants with SAD. SAD predicted less positive shifts in valence following days on which affect balance was predominantly negative (β = −.41, SE = .11, p = .001, R2 = .72, d = 1.04) and more negative shifts following days on which affect was predominantly positive (β = −.27, SE = .06, p < .001, R2 = .26, d = 1.0). Figure 2 depicts estimated group means in affect changes for each valence category. Follow-up analyses showed that these differences remained (ps < .004, ds > 0.7) when controlling for DEP and ANX. Additionally, MDD predicted less improvement in affect following negatively valenced days (β = −.63, SE = .15, p < .001, d = 1.25) and marginally more deterioration after positively valenced days (β = -.24, SE = .14, p < .094, d = 0.40), but no ANX effects were significant (ps > .2). Comorbid diagnoses explained an additional 29.1% of variance in changes after negative days, but no additional variance in changes after positive days.

Figure 2. Average Affect Change from Positive and Negative Valence by Diagnostic Group.

Notes. This graph shows the mean direction and intensity of affect shifts (error bars represent standard error of the mean) from days with predominantly negatively valenced affect (Positive – Negative < 0) and positively valenced affect (Positive – Negative > 0). Differences were significant at p < .01.

Does Instability Relate to Psychological Functioning?

All three instability measures were significantly positively correlated (rs > .47, ps < .001, ds > 1.0). Moreover, people who displayed unstable affect or self-esteem were more likely to display acute changes in NA, PA, and self-esteem (rs > .41, ps < .001, ds > 0.9). Those with high levels of NA experienced more instability (rs > .31, ps < .005, ds > 0.65) and more frequent acute changes (rs > .32, ps < .001, ds > 0.68) in all three measures. Those with low levels of PA and self-esteem experienced greater self-esteem instability and more NA and self-esteem acute changes (rs < −.33, ps < .003, ds > 0.7), but not other measures (ps > .5). These results suggest that instability—particularly NA and self-esteem instability—is associated with poorer daily psychological functioning.

We then used hierarchical regressions to see if instability was associated with global measures of social anxiety and depression above and beyond mean levels. We found a significant NA Mean Level × Instability interaction in predicting SIAS-S (β = −.25, t = −2.59, p = .011; d = 0.60, R2 = .38, ΔR2 = .06). Simple slopes (Aiken & West, 1991) showed that overall high NA levels predict more social anxiety, but for people who have lower mean NA (−1 SD), greater instability predicted more social anxiety symptoms (b = 5.15), and for those who have higher NA (+1 SD), greater instability predicted lower SIAS-S (b = −4.16). No other instability or interaction effects were significant (ps > .13).

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the dynamic nature of affect and self-esteem in people with SAD to offer a more nuanced understanding of how these psychological experiences fluctuate in everyday life. Compared to healthy adults, we found participants with SAD to experience unstable high NA, unstable low self-esteem, but stable low PA in their daily lives. In addition to greater instability in NA and self-esteem (though not when controlling for mean levels), participants with SAD had a higher probability of experiencing acute shifts in NA and self-esteem (but not PA) from day to day. Greater instability of NA and self-esteem may contribute to the disruptions in social relationships often reported by people with SAD, since the affect and self-esteem shifts they experience would be less meaningful and thus less useful to managing those relationships. Furthermore, people with SAD displayed a dysfunctional pattern of affective shifts in that they perseverated in negative affect states and displayed deficient maintenance of positive affect states.

Our finding that participants with SAD exhibited higher levels of NA in their naturalistic environment compared to healthy adults was consistent with daily diary findings in analogue samples (e.g., Farmer & Kashdan, 2012). Although people with higher NA levels had more unstable NA, this effect was less pronounced in people with SAD, suggesting that instability may be more prominent in this population, even at lower NA levels. Furthermore, mean level and instability of NA interacted in predicting social anxiety severity (i.e., instability predicted more severe social anxiety when mean levels were high). Confirming greater fluctuations in NA, we found that the SAD group was approximately three times more likely to experience acute shifts in NA. These results indicate that emotion difficulties in people with SAD extend beyond the experience of frequent or intense NA (e.g., anxiety). For people with SAD, experiencing unstable affect may lead them to view emotional experiences as particularly uncontrollable and thus threatening, contributing to attempts to avoid, conceal, and suppress the expression of these emotions—regulatory strategies theorized to maintain and exacerbate distress and impairment (Rapee & Heimberg, 1997).

Prior research has established a strong evidence base for positivity deficits in people with SAD (Kashdan et al., 2011), and our findings shed further light on this phenomenon. First, we confirmed prior research with analog samples that people with SAD have less intense daily PA on average. We also found that in healthy adults, experiencing more PA on average related to more stable PA, while the effect was inversed for the SAD group. This suggests that people with SAD generally experience low, stable PA, but those who do experience relatively more PA are likely to do so on intermittent and transient occasions (contributing to high PA instability). Further supporting our hypothesis that people with SAD have stable, low PA, the SAD and healthy control groups displayed no differences in rates of acute changes in PA.

Emotion regulation skills are necessary not only to down-regulate negative emotions but also to enhance or prolong positive emotions (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2006). Inability to savor and extend positive emotion states may not only limit exposure to positive experiences but also interfere with adaptive responses to stress (Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, & Tugade, 2000). Theorists suggest that people gravitate toward stable states (Carver & Scheier, 2001), which tend to be generally positive in terms of mood (Johnson & Nowak, 2002). This was true for the healthy adults in our sample, who generally tended to maintain positive affect with small affect changes from positively valenced states. Furthermore, they quickly shifted toward more positive affect after negatively valenced states. The SAD group did not display this pattern, instead experiencing more severe shifts toward negative affect from positively valenced states, and less strong positive shifts from negatively valenced states. These findings support literature on emotion regulation deficits in SAD, specifically in the greater use of down-regulating positive emotions and difficulty using strategies that effectively reduce negative emotions (e.g., Werner et al., 2011). Consequently, people with SAD may more quickly return to (more negative) baseline states after pleasant experiences. Our finding of people with SAD tending to shift more extremely toward negatively valenced affect following days with mostly positively valenced affect provides initial evidence for this possibility.

To our knowledge, this was the first study to examine daily self-esteem in people diagnosed with SAD, despite a growing body of literature and theory suggesting the role of low, unstable self-worth in this population. Our experience sampling data confirmed prior global self-report findings of low self-esteem (Baños & Guillén, 2000; Chartier, Hazen, & Stein, 1998; Izgiç, Akyüz, Doğan, & Kuğu, 2004; Leary, 2001). SAD participants also exhibited greater self-esteem instability, but this relationship was no longer evident when we took global self-esteem level into account. There is mixed evidence on whether it is necessary to control for mean levels in such analyses (Russell, Moskowitz, Zuroff, Sookman, & Paris, 2007). Providing further evidence for increased fluctuation, we found that SAD participants were three times more likely to experience acute shifts in self-esteem. Overall, these findings provide initial experience-sampling evidence that people with SAD have unstable, low self-esteem, consistent with cognitive models of the disorder (Clark & Wells, 1995; Moscovitch, 2009). Future research may address other aspects of these models by exploring how the context-dependency of self-esteem and self-esteem shifts relate to SAD and well-being.

Given the theoretical support and related empirical data, self-esteem instability may be an important marker for social anxiety symptoms. Overly variable self-esteem may reflect a miscalibrated gauge of one’s impression on others, such that instead of providing accurate information about the state of one’s relational value, people with SAD may react to small perceived depreciations in acceptance or anticipated devaluation rather than true rejection (Leary et al., 1998). In response, they may take extreme measures to avoid devaluation (e.g., with efforts to make positive impressions or by avoiding social interactions), or to avoid relational devaluation (e.g., by avoiding social interactions). Thus, variable self-esteem may serve as a possible mechanism for maintaining social anxiety symptoms. Alternatively, self-esteem instability may represent flexibility and/or destabilization of entrenched beliefs when it precedes the learning of novel associations, as in cognitive behavior therapy (e.g., Hayes, Laurenceau, Feldman, Strauss, & Cardaciotto, 2007). Notably, given that our data collection was during a random two-week segment of life (not a transition stage), the latter explanation is less likely.

To date, studies of self-esteem instability have used measures of variability (e.g., standard deviation) to capture this construct (e.g., Kashdan, Julian, et al., 2006; Kernis, Paradise, Whitaker, Wheatman, & Goldman, 2000). Self-esteem variability predicted vulnerability to depression (Kernis et al., 1998; Roberts, Kassel, & Gotlib, 1995), stress reactivity (Greenier et al., 1999), interpersonal aggression (Kernis, Grannemann, & Barclay, 1989), and impaired well-being (Kashdan, Uswatte, et al., 2006). By analyzing self-esteem instability with a measure that incorporated a temporal aspect of self-esteem fluctuations, we provided additional evidence for unstable self-esteem relating to poorer daily well-being.

It is worth noting that some prior research has suggested that instability may be adaptive when self-esteem levels are generally low, contributing to people using more adaptive coping strategies under stress (e.g., Kernis, Cornell, Sun, Berry, & Harlow, 1993). However, low self-esteem (even when variable) still increased the risk of developing depression over time, particularly when individuals experience chronic daily stress (Kernis et al., 1998). This relationship may help explain why in cases where SAD is comorbid with depression, social anxiety symptoms tend to precede depressive symptoms (Merikangas & Angst, 1995).

This research adds novel understanding to the phenomenology of SAD by taking an experience-sampling approach to investigate shifts and fluctuations of psychological states over time. Our findings build on prior SAD research that focused exclusively on global self-esteem, PA, and NA (e.g., T. A. Brown, 2007; Leary, 1983), or relied on mean daily affect levels (Kashdan & Steger, 2006). By using experience-sampling methods, we were able to examine affect and self-esteem as dynamic, contextualized constructs (see Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003; Nezlek, 2012). Additionally, asking participants to describe their experiences over the course of several weeks with online diaries with time-stamped entries minimized some of the limitations of retrospective reports (Robinson & Barrett, 2010; Scollon, Kim-Prieto, & Diener, 2003), allowing us to study affect and self-esteem shifts in their natural, spontaneous context with greater ecological validity (Csikszentmihalyi & Larson, 1987). In fact, comparing ESM data with global self-reports has shown only moderate agreement on instability and variability, and poor agreement on affect changes (Kernis et al., 1992; Solhan, Trull, Jahng, & Wood, 2009), which suggests that people have little insight into the degree of fluctuations they experience.

While our methods improved over global assessments and aggregation of assessment across time, our investigation was limited in that we did not examine the sources of day-to-day fluctuations or examine more complex sequences over time. Prior time-series research has demonstrated that self-esteem tends to covary with experienced affect (Nezlek, 2005) and experienced stressors (Greenier et al., 1999). Future studies might use multilevel growth curve modeling to examine temporal dependency of these constructs and the relationship of instability to emotional reactivity and contextual factors.

We compared a sample of participants carefully diagnosed with SAD using a well-validated clinical interview with a carefully screened healthy control group. However, 57.5% of the SAD group had at least one secondary comorbid diagnosis, consistent with epidemiological comorbidity research (Merikangas & Angst, 1995). Thus, a possible alternative explanation for our findings is that instability and dysfunctional patterns in shifts of psychological experiences are features of psychological difficulties more broadly. This point is particularly relevant in light of transdiagnostic research demonstrating shared features among commonly occurring disorders (e.g., emotion regulation; Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010). Notably, all hypothesized effects in our study remained significant after controlling for comorbid depression and anxiety disorders, providing preliminary evidence that SAD uniquely contributes to instability. Future research with clinical comparison groups (e.g., major depressive disorder) may help clarify this question.

Although our findings need replication, this research has important clinical and research implications. Specifically, we found people with SAD to experience more instability of NA and self-esteem, and tend to perseverate in NA states but have difficulty maintaining PA states. These findings suggest that clinicians should consider incorporating strategies that enhance emotion regulation skills that help to accept or more effectively manage negative emotions as well as to prolong and intensify positive emotions. Prior work on therapies employing relaxation, guided meditation, and mindfulness indicates that these techniques can prolong positive experiences and enhance quality of life (Chesney et al., 2005). Although cognitive-behavioral interventions have been particularly effective for increasing self-esteem (Emler, 2001; Goldin et al., in press), studies have yet to examine self-esteem stability as a treatment outcome. Future studies examining affective and self-esteem stability longitudinally will help to understand the development of these constructs and to clarify whether instability is a vulnerability factor, a symptom that occurs during the course of SAD, or a consequence of the disorder that persists after recovery. Moreover, assessing instability over critical transition periods (e.g., psychotherapy) may help elucidate patterns important to therapeutic change (Hayes et al., 2007).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health (R21-MH073937) and the Center of Consciousness and Transformation at George Mason University to TBK and the National Institute of Drug Abuse (1F31DA029390) to ASF.

Footnotes

We also tested for group differences in within-person variability by comparing models that assume homogenous variance vs. heterogeneous variance. All three constructs were more variable for SAD participants. Deviance tests favored heterogeneous models for daily PA (χ2 = 12.66, p = .001), daily NA (χ2 = 91.05, p < .001) and daily SE (χ2 = 71.82, p < .001).

The critical value for acute change (90th percentile) was 1.36 for PA, 1.0 for NA, and 4.0 for SE.

SE instability was not significantly predicted by either of the comorbid diagnostic predictors (ps > .3).

Contributor Information

Antonina S. Farmer, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

Todd B. Kashdan, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

References

- Ai C, Norton EC. Interaction terms in logit and probit models. Economics letters. 2003;80:123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldao A, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Specificity of cognitive emotion regulation strategies: A transdiagnostic examination. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(10):974–983. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anestis MD, Selby EA, Crosby RD, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Joiner TE. A comparison of retrospective self-report versus ecological momentary assessment measures of affective lability in the examination of its relationship with bulimic symptomatology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48(7):607–613. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baños RM, Guillén V. Psychometric characteristics in normal and social phobic samples for a Spanish version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Psychological reports. 2000;87:269–274. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2000.87.1.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardone AM, Krahn DD, Goodman BM, Searles JS. Using interactive voice response technology and timeline follow-back methodology in studying binge eating and drinking behavior: Different answers to different forms of the same question? Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF. Discrete emotions or dimensions? The role of valence focus and arousal focus. Cognition & Emotion. 1998;12(4):579–599. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen R, Baetz M, Hawkes J, Bowen A. Mood variability in anxiety disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2006;91:165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen R, Clark M, Baetz M. Mood swings in patients with anxiety disorders compared with normal controls. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;78:185–192. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00304-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Turovsky J, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Validation of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale across the anxiety disorders. Psychological Assessment. 1997;9:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA. Temporal course and structural relationships among dimensions of temperament and DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorder constructs. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:313–328. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow D, Brown T, Hofmann SG. Effects of suppression and acceptance on emotional responses of individuals with anxiety and mood disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1251–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. On the self-regulation of behavior. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chartier MJ, Hazen AL, Stein MB. Lifetime patterns of social phobia: A retrospective study of the course of social phobia in a nonclinical population. Depression and Anxiety. 1998;7:113–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Darbes LA, Hoerster K, Taylor JM, Chambers DB, Anderson DE. Positive emotions: Exploring the other hemisphere in behavioral medicine. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;12:50–58. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1202_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DM, Wells A. A cognitive model of social phobia. In: Heimberg Richard G, Liebowitz MR, Hope DA, Schneier FR., editors. Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. pp. 69–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Psychology Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Brown TA, Meadows EA, Barlow DH. Uncued and cued emotions and associated distress in a college sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1995;9:125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1987;175:526–536. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM–IV: Lifetime Version (ADIS-IV-L) San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ebner-Priemer UW, Kuo J, Kleindienst N, Welch SS, Reisch T, Reinhard I, … Bohus M. State affective instability in borderline personality disorder assessed by ambulatory monitoring. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:961–970. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emler N. Self-esteem: The costs and causes of low self-worth. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer AS, Kashdan TB. Social anxiety and emotion regulation in daily life: Spillover effects on positive and negative social events. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2012;41:152–162. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2012.666561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Mancuso RA, Branigan C, Tugade MM. The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion. 2000;24:237–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1010796329158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin PR, Manber T, Hakimi S, Canli T, Gross JJ. Neural bases of social anxiety disorder: Emotional reactivity and cognitive regulation during social and physical threat. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:170–180. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldin Philippe R, Jazaieri H, Ziv M, Kraemer H, Heimberg RG, Gross JJ. Changes in positive self-views mediate the effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Clinical Psychological Science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/2167702613476867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green DP, Salovey P, Truax KM. Static, dynamic, and causative bipolarity of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:856–867. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenier KD, Kernis MH, McNamara CW, Waschull SB, Berry AJ, Herlocker CE, Abend TA. Individual differences in reactivity to daily events: Examining the roles of stability and level of self-esteem. Journal of Personality. 1999;67:187–208. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Kogan A, Quoidbach J, Mauss IB. Happiness is best kept stable: Positive emotion variability is associated with poorer psychological health. Emotion. 2013;13(1):1–6. doi: 10.1037/a0030262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AM, Laurenceau J-P, Feldman G, Strauss JL, Cardaciotto L. Change is not always linear: The study of nonlinear and discontinuous patterns of change in psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:715–723. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimberg RG, Mueller GP, Holt CS, Hope DA, Liebowitz MR. Assessment of anxiety in social interaction and being observed by others: The Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and the Social Phobia Scale. Behavior Therapy. 1993;23:53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AA, Heimberg RG, Coles ME, Gibb BE, Liebowitz MR, Schneier FR. Relations of the factors of the tripartite model of anxiety and depression to types of social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1629–1641. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izgiç F, Akyüz G, Doğan O, Kuğu N. Social phobia among university students and its relation to self-esteem and body image. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;49:630–634. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahng S, Wood PK, Trull TJ. Analysis of affective instability in ecological momentary assessment: Indices using successive difference and group comparison via multilevel modeling. Psychological Methods. 2008;13:354–375. doi: 10.1037/a0014173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL, Nowak A. Dynamical patterns in bipolar depression. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2002;6(4):380–387. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB. Social anxiety spectrum and diminished positive experiences: Theoretical synthesis and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:348–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Breen WE. Social anxiety and positive emotions: A prospective examination of a self-regulatory model with tendencies to suppress or express emotions as a moderating variable. Behavior Therapy. 2008;39:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Julian T, Merritt K, Uswatte G. Social anxiety and posttraumatic stress in combat veterans: Relations to well-being and character strengths. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:561–583. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Steger MF. Expanding the topography of social anxiety: An experience-sampling assessment of positive emotions, positive events, and emotion suppression. Psychological Science. 2006;17:120–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Uswatte G, Steger MF, Julian T. Fragile self-esteem and affective instability in posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1609–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Weeks JW, Savostyanova AA. Whether, how, and when social anxiety shapes positive experiences and events: a self-regulatory framework and treatment implications. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31:786–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keltner D, Kring AM. Emotion, social function, and psychopathology. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2(3):320–342. [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Cornell DP, Sun C-R, Berry A, Harlow T. There’s more to self-esteem than whether it is high or low: The importance of stability of self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1993;65:1190–1204. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.6.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Grannemann BD, Barclay LC. Stability and level of self-esteem as predictors of anger arousal and hostility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:1013–1022. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Grannemann BD, Barclay LC. Stability of self-esteem: Assessment, correlates, and excuse making. Journal of Personality. 1992;60:621–644. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Paradise AW, Whitaker DJ, Wheatman SR, Goldman BN. Master of one’s psychological domain? not likely if one’s self-esteem is unstable. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:1297–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Kernis MH, Whisenhunt CR, Waschull SB, Greenier KD, Berry AJ, Herlocker CE, Anderson CA. Multiple facets of self-esteem and their relations to depressive symptoms. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW. Affective instability: Toward an integration of neuroscience and psychological perspectives. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2010;24:60–82. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ. The stability of mood variability: A spectral analytic approach to daily mood assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1987;52:1195–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Csikszentmihalyi M. The experience sampling method. New Directions for Methodology of Social & Behavioral Science. 1983;15:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Social anxiousness: The construct and its measurement. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1983;47:66–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4701_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. Social anxiety as an early warning system: A refinement and extension of the self-presentation theory of social anxiety. In: Hofmann SG, DiBartolo PM, editors. From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001. pp. 321–334. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Downs DL. Efficacy, agency, and self-esteem. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1995. Interpersonal functions of the self-esteem motive: The self-esteem system as a sociometer; pp. 123–144. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Haupt AL, Strausser KS, Chokel JT. Calibrating the sociometer: The relationship between interpersonal appraisals and the state self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74(5):1290–1299. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Kowalski RM, Campbell CD. Self-presentational concerns and social anxiety: The role of generalized impression expectancies. Journal of Research in Personality. 1988;22:308–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ludbrook J. Multiple comparison procedures updated. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology. 1998;25(12):1032–1037. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1998.tb02179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1998;36:455–470. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Angst J. Comorbidity and social phobia: Evidence from clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 1995;244:297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF02190407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscovitch DA. What is the core fear in social phobia? A new model to facilitate individualized case conceptualization and treatment. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2009;16:123–134. [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. Distinguishing affective and non-affective reactions to daily events. Journal of Personality. 2005;73:1539–1568. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. A multilevel framework for understanding relationships among traits, states, situations and behaviours. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21:789–810. [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB. The SAGE Library in Social and Personality Psychology Methods. London: Sage Publications; 2012. Diary methods for social and personality psychology. [Google Scholar]

- Nezlek JB, Kuppens P. Regulating positive and negative emotions in daily life. Journal of Personality. 2008;76(3):561–579. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterwegel A, Field N, Hart D, Anderson K. The relation of self-esteem variability to emotion variability, mood, personality traits, and depressive tendencies. Journal of Personality. 2001;69(5):689–708. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.695160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:741–756. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JE, Kassel JD, Gotlib IH. Level and stability of self-esteem as predictors of depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences. 1995;19:217–224. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson MD, Barrett LF. Belief and feeling in self-reports of emotion: Evidence for semantic infusion based on self-esteem. Self and Identity. 2010;9:87–111. [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Heimberg RG, Brown PJ, Fernandez KC, Blanco C, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. More reasons to be straightforward: Findings and norms for two scales relevant to social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:623–630. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodebaugh TL, Woods CM, Heimberg RG. The reverse of social anxiety is not always the opposite: The reverse-scored items of the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale do not belong. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:192–206. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal R, Rosnow RL, Rubin DB. Contrasts and effect sizes in behavioral research: A correlational approach. x. New York, NY, US: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC, Sookman D, Paris J. Stability and variability of affective experience and interpersonal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(3):578–588. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scollon CN, Kim-Prieto C, Diener E. Experience sampling: Promises and pitfalls, strengths and weaknesses. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2003;4:5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Solhan MB, Trull TJ, Jahng S, Wood PK. Clinical assessment of affective instability: Comparing EMA indices, questionnaire reports, and retrospective recall. Psychological Assessment. 2009;21:425–436. doi: 10.1037/a0016869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinkle SD, Lurie D, Insko SL, Atkinson G, Jones GL, Logan AR, Bissada NN. Criterion validity, severity cut scores, and test-retest reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in a university counseling center sample. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:381–385. [Google Scholar]

- Stopa L, Brown MA, Luke MA, Hirsch CR. Constructing a self: The role of self-structure and self-certainty in social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2010;48:955–965. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesser A. Toward a self-evaluation maintenance model of social behavior. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 21. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 181–227. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RJ, Mata J, Jaeggi SM, Buschkuehl M, Jonides J, Gotlib IH. The everyday emotional experience of adults with major depressive disorder: Examining emotional instability, inertia, and reactivity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:819–829. doi: 10.1037/a0027978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trull TJ, Solhan MB, Tragesser SL, Jahng S, Wood PK, Piasecki TM, Watson D. Affective instability: Measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:647–661. doi: 10.1037/a0012532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Regulation of positive emotions: Emotion regulation strategies that promote resilience. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;8:311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Von Neumann J, Kent RH, Bellinson HR, Hart BI. The Mean Square Successive Difference. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1941;12:153–162. [Google Scholar]

- Waschull SB, Kernis MH. Level and stability of self-esteem as predictors of children’s intrinsic motivation and reasons for anger. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA. The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. University of Iowa; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Carey G. Positive and negative affectivity and their relation to anxiety and depressive disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:346–353. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner K, Goldin P, Ball T, Heimberg R, Gross J. Assessing emotion regulation in social anxiety disorder: The emotion regulation interview. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2011;33:346–354. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JK, Rapee RM. Self-concept certainty in social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:113–136. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Beloch E. The impact of social phobia on quality of life. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;11:15–23. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]