Abstract

The need for parenting and relationship strengthening programs is important among low-income minority parents where the burden of relational and parental stressors contributes to relationship dissolution. We examine these stressors among young parents. Data were collected from four focus groups (N = 35) with young parents. Data were audio-recorded and transcribed. Inductive coding was used to generate themes and codes, and analysis was completed using NVivo. Relationship and parenting challenges, values, and areas of need were the three major themes that emerged. Women's relationship challenges were family interference and unbalanced parenting, and men reported feeling disrespected and having limited finances. Common relationship challenges for women and men were family interference and unbalanced parenting. Both genders valued trust, communication, and honesty in relationships. Areas of need for women and men included: improving communication and understanding the impact of negative relationships on current relationships. Parenting challenges for women were unbalanced parenting, child safety, and feeling unprepared to parent; men reported limited finances. Both genders valued quality time with child to instill family morals. Areas of need for women and men included learning child discipline techniques and increasing knowledge about child development. Finally, women and men have relationship and parenting similarities and differences. Young parents are interested in learning how to improve relationships and co-parent to reduce relationship distress, which could reduce risk behaviors and improve child outcomes.

Keywords: Family Relations, Parenting, Gender

Becoming a parent is a cause of stress and transition for adolescents and young adults. Young couples are still developing their romantic relationships and interpersonal skills when they need to focus on childrearing, leading to increased stress and conflict in their relationships (Cox, Paley, Payne, & Burchinal, 1999; Florsheim et al., 2003). Young, low-income couples face a number of challenges. Young mothers are more susceptible to the adverse effects of low levels of social support than older mothers (Gonzalez, Jones, & Parent, 2014). For young fathers, a desire to provide material support for their children is often difficult (Rhein et al., 1997). While the challenges for young mothers are well established, literature pertaining to young, low-income fathers largely discusses challenges to father involvement, rather than their actual experiences as a parent and partner.

Furthermore, the relationship challenges that young, often unmarried, parents face can affect their parenting and children. Unmarried mothers were more likely to report not trusting their partner, instances of domestic violence, relationship dissolution, and partner turnover than married mothers (Dush, 2011; Kershaw et al., 2014). In a previous study, we found that 50% of relationships between young parents ended by 15 months postpartum, with dissolution rates highest from 9 to 15 months postpartum (Kershaw et al., 2010). We need to better understand what is happening between young parenting couples during the postpartum period that is placing them at risk for relationship dissolution. Little is known about the relationship and parenting challenges that young parents go through that may exacerbate relationship conflict and dissolution.

Becoming a parent during adolescence and young adulthood has been linked to a variety of adverse consequences for both mother and child, including higher sexually transmitted disease risk, child behavioral problems, and less mental health stability (Akinbami, Schoendorf, & Kiely, 2000; Ickovics, Niccolai, Lewis, Kershaw, & Ethier, 2003; Kershaw et al., 2003; Niccolai, Ethier, Kershaw, Lewis, & Ickovics, 2003). Strong relationships may be protective against some of these adverse consequences. Research suggests that strong relationships among young parents have positive effects on the well-being of the mother and child (Ackerman, Brown, D'Eramo, & Izard, 2002; Cutrona, Hessling, Bacon, & Russell, 1998; Gavin et al., 2002; Gee & Rhodes, 1999; Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 1997; Milan et al., 2004). A positive relationship between the father and mother has been demonstrated to have positive effects for the child, including better psychosocial adjustment and cognitive development, and decreased behavioral problems (Cutrona et al., 1998; Hetherington & Stanley-Hagan, 1997).

The need for parenting and relationship strengthening programs is particularly important among low-income minority populations. Socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and gender roles can make the navigation of parenthood particularly challenging for young couples. In low-income couples, mothers' parenting stress is impacted by the amount of financial and caregiving support they receive from fathers; the support of fathers, however, is affected by the status of the couple's romantic relationship (Ryan, Tolani, & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). For young fathers, feelings of being unable to provide for their children and a lack of understanding of how to be a father are frequent challenges (Fleck, Hudson, Abbott, & Reisbig, 2013; Rhein et al., 1997). Young couples can also be affected by historical and societal norms that have devalued the importance of African American fathers (Lu et al., 2010); this is exemplified by low-income mothers' desire for the father of their child to be a co-parent, while simultaneously believing the father's involvement is not necessary (Kershaw et al., 2014). In addition, a review by Edin and Reed suggests that children from previous relationships can also pose challenges to the stability of a current relationship and that young, unmarried mothers often cite serious reasons for relationship dissolution, including partner violence and infidelity (Edin & Reed, 2005).

Researchers have explored gender-based differences in views about relationships (Eyre, Flythe, Hoffman, & Fraser, 2012) and parenting. Men and women cite different reasons for engaging in relationships. Women are more likely to view sexual and relationship satisfaction as linked, while men view them independently (Mark, Janssen, & Milhausen, 2011). Young women are more likely to place greater emphasis and sense of self-worth on the status of a current relationship, while young men are more likely to find the quality of a current relationship to be of greater importance (Baker & McNulty, 2011; Simon & Barrett, 2010), and to cite the need to feel supported as a requirement in a relationship (Mark et al., 2011).

Gender-based differences are also present for parenting challenges. Men report more situations of parenting failure due to their perceived ineffective parenting approaches and less child care self-efficacy than women (Hudson, Elek, & Fleck, 2001; Lansford et al., 2011). Men also more frequently associate parenting interest and ability with financial security (Barret & Robinson, 1990; Rhein et al., 1997). Women are likely to view the lack of caregiving abilities of the child's father as a challenge to parenting (Ryan et al., 2009) as well as general conflicts with the child's father and relatives (Wayland & Rawlins, 1997). Identifying gender differences in views about relationships and parenting among young minority parents could help researchers gain insight into the factors that lead to relationship conflict and dissolution.

Multiple programs to help young, low-income parents develop skills and improve relationships have been implemented with varying degrees of success (McHale, Waller, & Pearson, 2012; Petch, Halford, Creedy, & Gamble, 2012; Wilde & Doherty, 2013). The Building Strong Families Project focused on relationship strengthening during the transition to parenthood and was aimed specifically at unmarried, low-income couples enrolled at eight different sites (Wood, Moore, Clarkwest, Killewald, & Monahan, 2012). At 36 months' follow-up, the Building Strong Families Project had no effect on the quality of couple's relationships, nor did it improve the likelihood that they would stay together. However, at one center, there were significant improvements in relationship stability and the likelihood that a child would still be living with both parents by age 3 (Wood et al., 2012). The Supporting Father Involvement study, which was tested with a sample of mostly low-income parents and compared a couple's program to a program aimed solely at fathers, found that the program that involved both members of a couple yielded lower levels of parenting stress and better parenting satisfaction outcomes than the fathers-only program, while both successfully increased fathers' engagement with their children (Cowan, Cowan, Pruett, Pruett, & Wong, 2009).

The Strong Couples–Strong Children program sought to increase relationship quality among low-income, unmarried parents, with a specific emphasis on the role of fathers. The program was successful in improving relationship satisfaction and communication skills (Charles, Jones, & Guo, 2013). The Supporting Healthy Marriage program was unique in that it sought to enroll parenting couples who were already married. Positive effects, although small, were seen for marital relationships and individual psychological functioning (Hsueh et al., 2012).

In a meta-analysis of marriage and relationship education programs with a focus on low-income couples, 15 programs targeting low-income couples were identified. The authors found that the programs yielded modest positive results in the areas of relationship quality, commitment, and communication skills. However, it was noted that only three of these programs were rigorously evaluated with a control group, one being the Supporting Father Involvement study (Cowan et al., 2009).

Despite the many programs, the noted challenges suggest that to improve relationship and parenting for low-income minority parents, programs should be geared toward building secure relationship attachments and intimacy. A program that includes factors shown to promote strong relationship functioning and stability is extremely important for young parents experiencing increased relational stress (Johnson & Greenberg, 1994).

If we are able to improve the relationships of young parents, we have the possibility of not only improving their parenting but also improving the overall well-being of men, women, and children. To do this, we need to better understand factors that contribute to stable and unstable relationships in young parents. Furthermore, we need to understand how relationship and parenting challenges and values may differ between men and women to create programs that have maximum impact on young fathers, mothers, and children.

In this study, our goal was to understand gender similarities and differences about relationships and parenting among young parents and how we could use the information for future intervention development. This study adds to the literature by taking a qualitative understanding of relationship and parenting challenges of young parents, and how those challenges may differ by gender. The purpose of this qualitative formative study was to gather data on relationship and parenting challenges, values, and areas of need among young, poor, mostly minority parents. We also examined the influence of gender across challenges, values, and needs. To avoid participant leading, we did not focus on specific challenges (e.g., finances) for young parenting men and women identified in the literature so as to ascertain authentic perspectives. Instead, we posed broadly framed questions pertaining to relationships and parenting and recognized that participants' responses may be unique to their gender and life experiences. We report our findings from this initial development stage of a couple-based behavioral intervention.

Method

Study Procedures

For this study, we conducted four focus groups. Participants were recruited from a former longitudinal observational study of young pregnant couples (Kershaw, Arnold, Gordon, Magriples, & Niccolai, 2012) and from a local community agency providing services to low-income families. Staff contacted potential participants and posted flyers at the participating local agency. Interested clients contacted staff members for further information about the study.

The focus groups were led by an experienced male and female group facilitator from the community agency. Each facilitator led two groups. All four focus groups were audio-recorded using a digital recorder; and the recording lasted approximately 90 minutes. The participants received a $30 incentive for their participation at the end of the group. Procedures for the focus groups were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Participants

Inclusion criteria included: female age 14–25 years; male age 14 and older; have a child 0–5 years old; heterosexual; and English-speaking. The focus groups varied in composition and consisted of a couples group (males and females were both the biological parents of a child and were in a romantic relationship), a mixed-gender group (where members of the opposite gender were not a couple and did not know each other), a female-only group, and a male-only group. The purpose for the varied group compositions was to gather a diverse perspective on romantic relationships and parenting. We conducted two groups with mixed genders to provide males and females an opportunity to understand and augment the opinion of the opposite gender. We also conducted two same-gender groups to provide an opportunity for men and women to speak freely in a way they might not in the presence of the opposite gender. The purpose of this strategy was to provide variety in relationship and parenting contexts (e.g., single mothers, single fathers, intact biological parents) so we could gain multiple perspectives on relationship and parenting challenges for different relationship types. For instance, individuals who are no longer with the father or mother of the baby provide unique insight into factors that may relate to relationship dissolution that intact couples might not yet have. However, it should be noted that we did not purposively sample by different parenting configurations, and we did not get detailed data to identify how many of each configuration were in each focus group. So we probably did not have equal numbers across parenting configurations, may not have represented all types of parenting configurations, and are unable to compare themes across parenting configurations. Our sampling strategy was merely to promote variety and diversity across and within groups.

The focus groups were conducted over the course of 3 months. Research staff began recruitment approximately 2 weeks prior to the facilitation of each group. The research staff and staff from the local agency recruited according to the inclusion criteria above. Because some individuals completed the recruitment screening form incorrectly and research staff did not detect screening errors, four females over age 25 were admitted into the study. All participants were informed during recruitment of the type of group that they would participate (i.e., couple, mixed-gender, and male- and female-only). Potential participants had to be a in a romantic relationship with one another to participate in the couple focus group and meet the gender specification for the male- and female-only focus groups. For the mixed-gender group, participants who arrived to the focus group with their romantic partner were permitted to remain in the group together. However, when we conducted the gender-specific focus groups, all participants who arrived with their romantic partner were separated into their respective gender group.

There were a total of 35 (17 female and 18 male) focus group participants. Fifty-four percent were Black, 34% Hispanic, and 12% White. The mean age was 23 for females and 24 for males. Age was unknown for 6% of females and males. The couples focus group consisted of four heterosexual couples with a mean age of 18 years for females and 20 years for males. Participant racial composition for the couples group consisted of four Blacks and four Hispanics. Four males and three females comprised the mixed-gender focus group, and participants' mean age was 20 years for females and 22 years for males. This group included five Hispanic and two White participants. The gender-specific focus groups consisted of 10 females and 10 males with a mean age of 25 and 27 years, respectively. The racial composition data for the gender-specific groups were incomplete. One Black male and three Black females participated in the gender-specific groups; the racial background for nine male and seven female participants was not reported. All participants resided in the New Haven metropolitan area. Participants recruited from the former longitudinal study had an average household annual income of $17,500 for men and $12,500 for women. Participants recruited through the local community agency had an average household annual income of $10,000 and received public assistance such as the Women, Infants, and Children program, food stamps, and cash assistance. We unfortunately did not collect specific data from these participants on their current employment status. More description of the sample and focus groups is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Description of Participant Relationship, Co-parenting, and Cohabiting Status.

| Focus Group | Men | Women | In Romantic Relationship/Co-parents | No. of couples present at focus group | Cohabiting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed Gender | 4 | 3 | 6 (85.7%) | 1 | 4 |

| Men | 10 | 0 | 3 UNK: 7 | N/A | 3 UNK: 7 |

| Women | 0 | 10 | 5 UNK: 5 | N/A | 3 UNK: 6 |

| Couples | 4 | 4 | 8 (100%) | 4 | 0 |

| Totals | 18 | 17 | 22 (62.9%)* 12 UNK: (34.3%) | 5 | 10 (28.6%)* 13 UNK: (37.1%) |

UNK = Unknown. We did not ask the mixed-gender, men-only, and women-only groups if they were in romantic relationships and co-parenting with the mother/father of the child, nor did we ask whether they were cohabiting. The values (3, 3, 5, 3) considered known in these cells were based on relationship and cohabiting status reported in a previous participant data file from which a portion of participants were recruited.

Individuals not included in the total number and percentage of participants.

Measures

The research team developed an interview schedule for the focus groups. The interview schedule consisted of 29 questions and 19 of these questions pertained to relationships and parenting: relationship challenges and values (11 questions); parenting challenges and values (4); and relationship and parenting areas of need (4). Relationship questions posed to the groups included defining ideal relationships, argument triggers, communication, influences on relationships, and ways to improve relationships. Questions pertaining to parenting included defining ideal parenting characteristics, their main parenting stressors, and parenting topics they would like to learn more about.

Data Analysis

All focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were checked against the audio files for accuracy. We used the grounded theory framework (Hsueh et al., 2012) to content analysis and employed the constant comparative method (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The project investigators read the transcripts line by line to generate themes and codes using the open coding approach (Padgett, 1998). They used keywords in the text to generate major categories and codes and discussed the themes that emerged. Investigators then used the axial coding approach to group themes into thematic categories (Padgett, 1998). The thematic categories and codes were used to create a coding tree to provide structure for coding the data. The investigators reconciled the coding tree by reviewing and comparing each large theme and corresponding codes derived from the data. The data were coded using the reconciled coding tree in NVivo 8 (QSR International Pty Ltd., Burlington, MA, USA), qualitative data management software. Research assistants, who served as coders, selected several transcripts to check for inter-rater reliability. Any discrepancies in coding were discussed until a consensus was reached between the two coders. Once all transcripts were coded, a coding comparison query was conducted as a final check for inter-rater reliability—coding comparisons for the focus groups were within 94% to 100%. Matrix coding queries were conducted to assess the frequency with which codes were referenced in the data. These queries were used to identify the most frequently occurring responses made by participants. Matrix coding queries were also conducted stratified by gender to assess gender differences in response to focus group questions.

Results

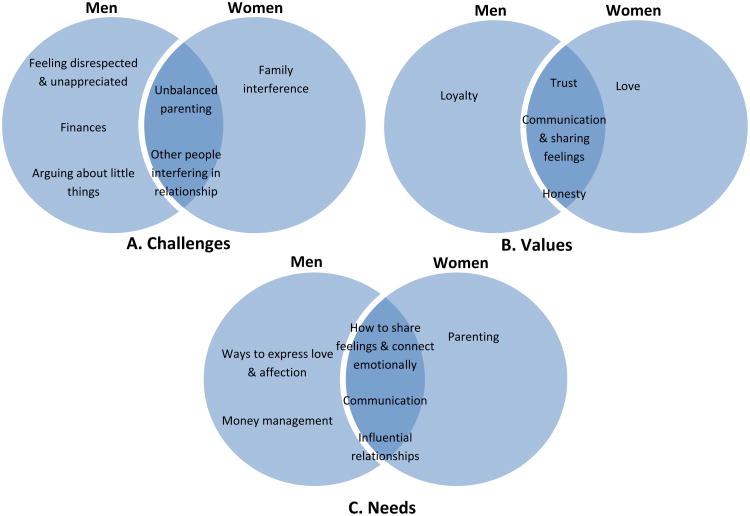

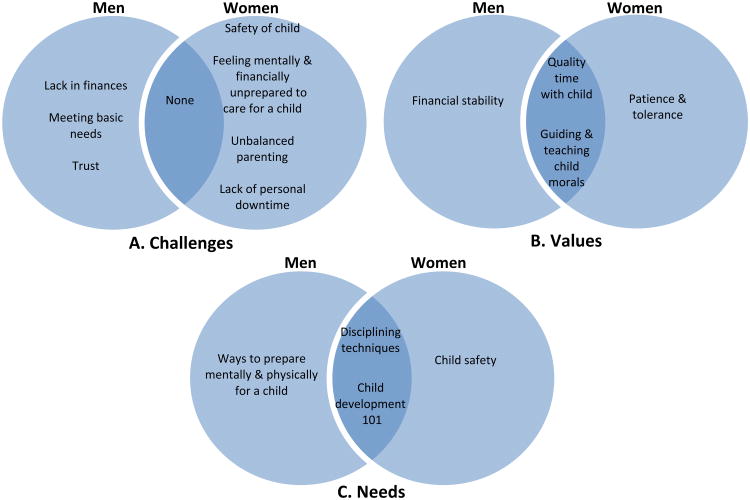

The findings fell into three themes: relationship and parenting challenges, relationship and parenting values, and relationship and parenting areas in need of development. We assessed common themes across gender, as well as themes unique to men and women. It should be noted that given the variability in the groups (e.g., male-only, female-only, mixed-gender, couples), we assessed possible differences in themes across different group types and found that the themes were fairly consistent (see Figures 1a–c and 2a–c); the only major differences were between males and females (e.g., male themes from male-only groups were consistent with male themes from mixed-gender and couples groups).

Figure 1.

Relationships.

Figure 2.

Parenting.

Relationships

Relationship challenges

For women, interference by other people was the most commonly cited relationship problem. Family interference, in particular, was the most cited interference type. One female participant described how family caused disagreements in her relationship:

With me it's not just me and my boyfriend, we get into arguments, we don't like stuff that his family does cause we live in their house. So we don't like what they do so we disagree a lot, me and him…. (Mixed-Gender Focus Group, 2011)

Another female participant reiterated how family interference adversely affected her relationship: “In my relationship, it's only about his momma. That woman is so nosy, she won't mind her business, and it ruined my relationship, basically” (Women's Focus Group, 2011). They also reported relationship interferences by other women, such as women who were in previous relationships with their partners. In addition, women identified unbalanced parenting as a relationship challenge and a trigger for arguments. For instance, a participant listed the three main unbalanced parenting issues that cause problems between she and her partner: “…mostly about the baby—who does what with the baby, who buys what for the baby, who watches the baby” (Couples Focus Group, 2012).

For men, feeling disrespected and unappreciated was the most commonly cited relationship problem. Being ignored, lied to, and cheated on constituted their feelings of being disrespected and unappreciated. Men also reported unbalanced parenting as a relationship challenge. Most unbalanced parenting issues pertained to whose responsibility it was to watch and supervise the child. One male participant stated:

Well, basically, it's whether or not you're watching the baby. I'm watching the baby … depending on time and date. If she has to do something I'd like to know before the time and place just in case I don't have nothing to do or I do have something to do cause I do support my son. (Couples Focus Group, 2012)

Men also stated that arguments about “little things” such as clothing choice, not giving their partner enough compliments, and not consistently following the customs of their home contributed to relationship challenges.

Relationship values

Women cited communication as most important in a relationship. The women explained that communication helped to reduce arguments and frustrations, helped to express love for their partner, and helped to build trust in their relationship. One participant expressed how communication was beneficial in her relationship:

Well I know I have a good relationship with the father of my child because there is not too many decisions that we make apart from each other, like we always consult each other because if that's my other half, whatever I do is going to affect him, just like whatever he does is going to affect me so we talk about virtually everything, even stuff we shouldn't talk about, we still talk about before it's done so. (Women's Focus Group, 2011)

Women also referenced trust and honesty as being important in a relationship. The importance of trust and honesty in a relationship was conveyed more often in the context of communication and confiding in their partner. For example, one participant stated:

Well, I think it's like they said, when you talk about everything that's like really really important. You don't want there to be secrets between you and the person you plan on spending your life with, or you don't want to feel like you have to hide things from them. (Women's Focus Group, 2011)

Men cited trust as most important in a relationship, followed by communication, honesty, loyalty, and sex. Trust was discussed in the context of relationship fidelity. One participant stated: “Trust is the key, without trust, there's no relationship” (Men's Focus Group, 2011). The importance of trust and fidelity was reiterated by another: “When there's trust, when you're working, you don't have to worry about what your wife is doing. When you got that trust, you don't have to worry about nothing and what she's doing back home” (Men's Focus Group, 2011). Men also cited sex as important in relationships. Sex, however, was not a frequently cited factor compared with other factors (i.e., trust, communication, honesty). Men associated more sexual episodes with increased trust in the relationship.

Regarding communication, men expressed the benefits of communicating in relationships, such as sharing feelings, understanding one another, and being “on the same page.” One male participant explained why communication was an important aspect of relationships:

Another thing, when you working toward progression in a relationship, the first thing you need to do is to identify what it is that you guys need to work on and the way to do that is through communication. So communication is everything. You gotta express yourself to your significant other or you're not gonna have that chemistry anymore because you don't have that communication so now I don't know what you're thinking and you don't know what I'm thinking. (Men's Focus Group, 2011)

Areas of relationship need

For women, communication was the most frequently cited topic. Women wanted to learn more about how to communicate with their partner so that they could share their feelings, discuss the future of their relationship, address past relationships and hurts, increase understanding between them, get their partner to open up emotionally, and avoid arguments. One participant expressed her desire to avoid arguments:

For me, how to deflect an argument or learning how not to feed into their B.S. You know they just want to argue because of something that they say … the way they say it … way their face is looking. So, how to deflect the argument and not even care. Act like them sometime, sometimes you want to argue and they know what to say to make you argue. (Women's Focus Group, 2011)

The women also wanted to learn how to avoid relationship mistakes that their parents made and to understand how these influential relationships impact their relationship with their partner. The participants frequently cited that their parents' relationships were “horrible” and involved physical abuse, drug abuse, infidelity, parental incarceration, and home instability. One participant describes her parents' abusive relationship:

Well … for one they fist fight, like fist fight still to this day. They won't leave each other and I don't know why …. why they don't just leave each other and just leave it alone … but it's horrible, they fight, they say stuff like … if words could kill they would have both been dead like years and years ago. There's no communication, and I really don't think that they like each other. I think they just love each other. (Women's Focus Group, 2011)

Men also wanted to learn how to improve communication. Communication focused on learning how to understand one another, talk about the past, and verbally expressing love. The dialogue below highlights a discussion about the difficulties men experience in telling their partner that they love them, which was their main reason for wanting to learn how to communicate.

| Male #13 | “You know you love a female but you just don't say it.” |

| Male #16 | “Like he saying you want to tell her how much you love them but at the same time you don't want to act too mushy.” |

| Male #13 | “Yea, you gotta maintain your manhood.” |

| Male #9 | “I think it's about a lot of pride.” (Men's Focus Group, 2011) |

The men also wanted to learn how influential relationships affected their relationships and how to avoid repeating negative relationship cycles. The men reported family incidences of physical abuse, drug use, parental incarceration, infidelity, and overall spousal mistreatment. One participant describes the impact of his parents' relationship and its influence on how he chose to treat romantic partners: “I always grew up thinking I'm never going to be like him [dad] cuz my mom …. she's a good mom so I didn't want to take anybody for granted like he did” (Couples Focus Group, 2012).

Parenting

Parenting challenges

Women cited child safety and feeling unprepared to care for and raise a child as leading parenting challenges. The women focused on their child's physical safety and the fear of their child getting hurt. One participant stated:

Because they can get hurt, they can fall, fall down the stairs. Anything …. my son fell down the stairs one time and I panicked cause I didn't know what to do. I always stress about his safety, I tell him do not run up and down the stairs, don't run through the hallways, don't do this, don't do that. (Women's Focus Group, 2011)

Women also indicated that parenting was challenging because they at times felt unprepared to care for and raise a child. These feelings were attributed to becoming a mother at a young age: “I think it's a big problem when you have kids young, because usually when you have kids young, you don't think about the way you want to raise your child” (Mixed-Gender Focus Group, 2011).

Other parenting challenges for women included a lack of personal downtime due to unbalanced parenting. For example, one mother talked about the importance of being a full-time parent and how frustrations arose when parenting responsibilities were not divided evenly between her and the child's father:

I think, like what I said before, you can't be a parent when you want to be a parent, and like whenever something happened to my son or whatever, like I needed him [the baby's father] for something and if he didn't feel like doing it, he wouldn't do it … but like I have no choice, you know, like there was times that I brought him to his father's and he was like oh no … like he was right in the house, and I brought him all the way there, but he was like oh I'm busy, whatever doing shit he shouldn't be doing anyways. But you can't just choose when you want to be a parent. It's a full-time job and not a part-time job. (Mixed-Gender Focus Group, 2011)

For men, having finances to meet basic family needs was the most frequently referenced parenting challenge. This included paying bills and purchasing essential items like food and diapers. A male participant highlighted the gender differences as he explained the parental stressors he experienced as opposed to his female partner:

I think I stress about going to work and stuff, paying the bills, having enough money to buy all the things. … I think she stresses more about being there, taking care of the baby. I work like 80 hours a week, 70 hours a week just to pay the bills. (Mixed-Gender Focus Group, 2011)

Parenting values

For women, spending quality time with their child and guiding and teaching their child morals were the two most frequently cited themes. They placed emphasis on spending quality time as a way to demonstrate love and playfulness toward their child. Spending quality time was also a way to instill morals and guidance that would direct them in the “real world.” As one participant stated: “That's the point of being a parent, is to teach somebody [their child] how to do it on their own…” (Women's Focus Group, 2011). Women also cited patience and tolerance as important in parenting. This theme mostly referenced the importance of patience when disciplining their children, especially for mothers who were the primary child care providers.

For men, the most common themes that emerged were spending quality time with their child and guiding and teaching their child. For example, one male participant explained how spending time is more important than anything else: “To honor and cherish every moment you spend with him. Time is the most important you can spend with your child cause you can't get time back. Instead of spending money on your child … spend time with them” (Couples Focus Group, 2012). Men considered guiding and teaching their child as “showing them the way of life” and “teaching the child what is right and wrong.”

Areas of parenting need

For women, learning disciplining techniques was the most commonly cited parenting topic of interest. For example, one female participant mentioned discipline as something she would like to learn about because of the inconsistencies in disciplining young children: “I think for me … we discipline our kid our way … everybody disciplines their kid different but sometimes it just don't work … they just don't care” (Mixed-Gender Focus Group, 2011). The women also wanted to learn more about child safety and child development, specifically about the infant (e.g., correct positioning of baby in a crib), toddler (e.g., potty training), and teenage (e.g., managing difficult teens) stages.

For men, the most commonly cited parenting need was to learn ways to prepare mentally and physically for a child. For example, one male participant stated:

You just have to be ready for everything. Being a young parent, nothing is certain. When I first heard that she was first pregnant, being a dude … I know we all did it … I was like damn I don't want to do this … I can't do this man …. like I was thinking of ways to convince her not to have it … but then like 9 months later a little dude came out and damn you know … like you gotta be ready for everything … and to tell you the truth … you're never ready … you just gotta be open-minded. (Couples Focus Group, 2012)

In addition to learning to prepare for a child, men also wanted to learn about disciplining techniques and child development. More specifically, they wanted to learn the best ways to discipline a child that would bring behavioral correction and not cause physical harm. They also wanted to learn the proper discipline techniques to establish an authoritative role and boundary setting as a parent. Finally, men wanted to better understand child development and to be aware of things they should look for and expect as their child grows.

Discussion

Among this small sample of young parents, our findings show that, for the most part, young females and males had similar views on relationships and parenting. However, there were some differences between males and females. Males and females differed the most on factors that were challenging to relationships and parenting, and they differed the least on values central to relationships and parenting. This suggests that although males and females may have different experiences and perspectives around relationships and parenting, their core beliefs about relationships and parenting are fairly similar. The biggest difference between males and females was for parenting challenges, where no major themes were shared between males and females. As seen in Figures 1a–c, the most commonly cited relationship challenge for females was the relationship interference by others. Social interference from others such as family members and friends is associated with romantic relationship dissolution (Felmlee, Sprecher, & Bassin, 1990; Johnson & Milardo, 1984).

Females, in particular, continue to maintain and solicit support from family and friend networks while in romantic relationships, but when family and friend networks disapprove of romantic relationships, these networks become strained and may ultimately cause strain and romantic relationship dissolution (Bryan, Fitzpatrick, Crawford, & Fischer, 2001). Females may experience greater distress from social interference because compared to males supportive networks are more salient to females (Bryan et al., 2001). They are more likely to have frequent contact with family and friends (Eggebeen & Hogan, 1990), value the degree of support (Cotton, Cunningham, & Antill, 1993), make greater strides to affect parents' reaction to or approval of their romantic relationships (Leslie, Huston, & Johnson, 1986), and seek to integrate their romantic partner into their family and friend networks (Bryan et al., 2001). Thus, females may experience greater burden from negative reactions and interferences to their romantic relationships by family and friends.

For males, feeling disrespected was the most important relationship challenge (see Figure 1a). Honesty and trustworthiness are associated with respect, which help to form secure attachments for couples (Frei & Shaver, 2002). Males seek partners who can operate as helpers and be supportive of personal and relational endeavors (Frei & Shaver, 2002). The support given by his female partner may serve as an indication of respect for his role as a partner and parent.

Similar to findings in previous parenting literature, unbalanced parenting among the couples may be attributed to relational conflict. Research has shown that relational conflict may result in the father's withdrawal from the mother and from the child (Pedro, Ribeiro, & Shelton, 2012), consequently, abandoning parental responsibilities. Relational conflict is also associated with negative parenting (e.g., rejection of child, lower parental warmth, and lower supportive responses to child (Pedro et al., 2012). Conflicts around unbalanced parenting may lead to increased strain on young parenting couples and may also contribute to relationship dissolution.

Another factor important to conflict resolution is communication, which was identified by both females and males as an important area in need of development (see Figure 1c). Females were interested in learning better communication techniques to avoid arguments, and both females and males wanted to learn how to communicate their feelings and connect emotionally with their partner. Communication in romantic relationships creates closeness and intimacy between partners and is essential to overall relationship satisfaction (Montesi, Fauber, Gordon, & Heimberg, 2011). Continued open communication allows for the individual to self-disclose and to be vulnerable with his/her partner. Couples in distress may struggle with poor communication skills, which undermine effective communication and contribute to relationship dissatisfaction (Montesi et al., 2011).

Further, our results suggest that programs need to be flexible and cover some different content for men and women, something that is not typically done in many of the existing programs and may explain some of the inconsistent effects found for these parenting programs (Charles et al., 2013; Cowan et al., 2009; Wood et al., 2012). For example, the influence of external members of the couples' social network (both in terms of interference and support), and imbalanced parenting responsibilities were more important for women. These themes could be explored in gender-separated breakout groups to help women learn strategies to manage external stressors and strengthen social support systems and to help men better understand familial influences on the functioning of their relationship, and skills to equitably distribute parenting responsibilities. Similarly, we found that men felt disrespected and underappreciated. Programs could bolster communication skill components in a way that helps men learn to specifically communicate when they feel undervalued, while at the same time teaching women to communicate with their partner in a way that shows respect and appreciation.

In this study, many young parents had not been exposed to healthy relationships and most of their parents struggled with communicating effectively. As a result of their exposure to difficult family conditions, females and males were interested in learning how their parents' volatile relationships influenced their own relationships and the decisions they make as partners and parents. Many of the participants reported abuse, instability, and infidelity in their parents' relationship; as a result, many wanted to learn ways to avoid repeating generational relationship dysfunction. Research suggests that intergenerational transmission of risk is common, particularly among low-income minority populations (Kershaw et al., 2014; Meade, Kershaw, & Ickovics, 2008; Sipsma, Biello, Cole-Lewis, & Kershaw, 2010).

Further, programs can highlight how unique experiences based on ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and gender may influence their perspectives on relationships. Given the differences between genders on relationship themes, programs could incorporate components that address these differences. Our study did not elucidate differences by ethnicity, but we asked participants how different cultures may influence parenting and relationship needs, and participants felt that their primary concerns and challenges would not differ much for different races and ethnicities (data not shown).

As many of the participants stated, becoming a parent is an emotional event. Emotional and mental stressors are not uncommon among parenting couples, but as seen in other studies, stressors are often amplified among young, low-income couples (Dakin & Wampler, 2008). Cumulative psychosocial stressors can lead to relationship dissolution (Carlson, McLanahan, & England, 2004; Ryan et al., 2009) and poor child outcomes (Evans & English, 2002). Our study participants were concerned with creating a warm and nurturing home environment for their child. These young parenting couples could benefit from learning how to communicate effectively, express empathy, resolve conflicts, and compromise to overcome stressors associated with being young parents.

Overall, the participants in this study experienced many obstacles as young, low-income parents. Maintaining relationships and parenting responsibilities require knowledge and specific relational skills that are typically lacking in young parents. A study limitation is that we conducted only four focus groups and had a small sample size overall and were not able to compare our findings across different parenting configurations (e.g., single mother, biological parents). Although we made efforts to recruit a variety of parents, we did not purposively sample different parenting configurations (e.g., single mother, single father, couple with children from different relationships). Therefore, we were unable to ascertain whether themes differed across these different parenting configurations.

Further, some types of parents were not included, limiting our generalizability. Same-sex parenting partners were not identified in this study, but low-income same-sex couples may experience unique challenges that relationship strengthening programs should address. These challenges may include social acceptance of same-sex coupling and legal same-sex parenting rights (Meezan & Rauch, 2005). Also, because there was no higher income comparison group, it was unclear whether the relationship and parenting challenges, values, and needs were unique to our study sample or simply a result of being young parents. Some of the challenges stated by participants overlap with previous studies of young, low-income parents, but the qualitatively expressed relationship and parenting values and needs were especially resonant among our study participants. When the young parents vocalized their values and needs, it demonstrated a desire to maintain their relationship and to be an effective parent.

A major strength of this study was that it was conducted with young couples and parents at risk for conflict and relationship dissolution. To our knowledge, this study is one of the first qualitative studies that have explored both relationship and parenting factors impacting low-income young couples and parents. Other qualitative studies that collected data from couples have focused on older couples and on narrower issues that impact relationships (Gibson-Davis, Edin, & McLanahan, 2005; Goff et al., 2006). Second, we focused on collecting data from minority low-income parents and couples. Most studies involving couples have focused on couples in therapeutic settings and have been conducted primarily with middle-class White couples (Christensen, Russell, Miller, & Peterson, 1998).

We found that young parents are eager to learn how to improve their romantic relationships and parenting knowledge and skills. Despite the challenges they face, there are opportunities to support parents in achieving and maintaining relational stability. Although this study was not specific to couples only, our next step was to develop a program for young parenting couples that focused on increasing knowledge and skills to reduce relational and parenting distress. Based on the focus group data and other formative research, existing literature, and principal components of emotion-focused therapy, we developed a 15-session couples intervention. The intervention focuses on strengthening parenting couples by improving couple attachment, communication, intimacy, empathy, and conflict resolution. The intervention is currently being implemented with low-income young parenting couples residing in a major northeast city, and initial process and outcome evaluations will be used to further develop and modify the intervention. We believe a program of this design will contribute greatly to improving relationship and parenting challenges and child developmental and behavioral outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Data for this paper came from a project supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R34MH094354, PI: Kershaw). Further support for this project came from the Yale Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS (5P30MH062294) and a HIV Training Grant that supported Dr. Albritton's efforts (T32MH020031). Special acknowledgements to our collaborating community partner Children's Community Programs, and a special thanks to Victoria Dancy and Timothy Brown for their dedication and commitment.

References

- Ackerman BP, Brown ED, D'Eramo KS, Izard CE. Maternal relationship instability and the school behavior of children from disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38(5):694–704. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinbami LJ, Schoendorf KC, Kiely JL. Risk of preterm birth in multiparous teenagers. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2000;154(11):1101–1107. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.154.11.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker LR, McNulty JK. Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100(5):853–873. doi: 10.1037/a0021884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barret RL, Robinson BE. The role of adolescent fathers in parenting and childrearing. Advances in Adolescent Mental Health. 1990;4:189–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan L, Fitzpatrick J, Crawford D, Fischer J. The role of network support and interference in women's perception of romantic, friend, and parental relationships. Sex Roles. 2001;45(7–8):481–499. doi: 10.1023/A:1014858613924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson M, McLanahan S, England P. Union formation in fragile families. Demography. 2004;41(2):237– 261. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles P, Jones A, Guo S. Treatment effects of a relationship strengthening intervention for economically disadvantaged new parents. Research on Social Work Practice. 2013;24(3):321–338. doi: 10.1177/1049731513497803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen LL, Russell CS, Miller RB, Peterson CM. The process of change in couples therapy: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 1998;24(2):177–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1998.tb01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Cunningham JD, Antill JK. Network structure, network support and the marital satisfaction of husbands and wives. Australian Journal of Psychology. 1993;45(3):176–181. doi: 10.1080/00049539308259136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Pruett MK, Pruett K, Wong JJ. Promoting fathers' engagement with children: Preventive interventions for low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(3):663–679. [Google Scholar]

- Cox MJ, Paley B, Payne C, Burchinal M. The transition to parenthood: Marital conflict and withdrawal and parent-infant interactions. In: Cox M, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Conflict and cohesion in families. Mahwah, NJ: Laurence Erlbaum Associates; 1999. pp. 87–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Hessling RM, Bacon PL, Russell DW. Predictors and correlates of continuing involvement with the baby's father among adolescent mothers. Journal of Family Psychology. 1998;12(3):369–387. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.12.3.369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dakin J, Wampler R. Money doesn't buy happiness, but it helps: Marital satisfaction, psychological distress, and demographic differences between low- and middle-income clinic couples. The American Journal of Family Therapy. 2008;36(4):300–311. doi: 10.1080/01926180701647512. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dush CMK. Relationship-specific investments, family chaos, and cohabitation dissolution following a nonmarital birth. Family Relations. 2011;60(5):586–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edin K, Reed JM. Why don't they just get married? Barriers to marriage among the disadvantaged. Future of Children. 2005;15(2):117–137. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggebeen DJ, Hogan DP. Giving between generations in American families. Human Nature. 1990;1(3):211–232. doi: 10.1007/BF02733984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre SL, Flythe M, Hoffman V, Fraser AE. Primary relationship scripts among lower-income, African American young adults. Family Process. 2012;51(2):234–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felmlee D, Sprecher S, Bassin E. The dissolution of intimate-relationships—A Hazard model. Social. Psychology Quarterly. 1990;53(1):13–30. doi: 10.2307/2786866. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleck MO, Hudson DB, Abbott DA, Reisbig AM. You can't put a dollar amount on presence: Young, non-resident, low-income, African American fathers. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2013;36(3):225–240. doi: 10.3109/01460862.2013.818744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Sumida E, McCann C, Winstanley M, Fukui R, Seefeldt T, et al. The transition to parenthood among young African American and Latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(1):65–79. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.17.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frei JR, Shaver PR. Respect in close relationships: Prototype definition, self-report assessment, and initial correlates. Personal Relationships. 2002;9(2):121–139. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gavin LE, Black MM, Minor S, Abel Y, Papas MA, Bentley ME. Young, disadvantaged fathers' involvement with their infants: An ecological perspective. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(3):266–276. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00366-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee CB, Rhodes JE. Postpartum transitions in adolescent mothers' romantic and maternal relationships. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly-Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1999;45(3):512–532. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM, Edin K, McLanahan S. High hopes but even higher expectations: The retreat from marriage among low-income couples. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(5):1301–1312. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00218.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goff BS, Reisbig AM, Bole A, Scheer T, Hayes E, Archuleta KL, et al. The effects of trauma on intimate relationships: A qualitative study with clinical couples. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2006;76(4):451–460. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.76.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez M, Jones D, Parent J. Coparenting experiences in African American families: An examination of single mothers and their nonmarital coparents. Family Process. 2014;53(1):33–54. doi: 10.1111/famp.12063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington E, Stanley-Hagan, Margaret M. The effects of divorce on fathers and their children. In: Lamb MEE, editor. The role of the father in child development. 3rd. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, NJ: 1997. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh J, Alderson DP, Lundquist E, Michalopoulos C, Gubits D, Fein D, et al. The supporting healthy marriage evaluation: Early impacts on low income families. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson DB, Elek SM, Fleck CM. First-time mothers' and fathers' transition to parenthood: Infant care self-efficacy, parenting satisfaction, and infant sex. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. 2001;24(1):31–43. doi: 10.1080/014608601300035580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickovics JR, Niccolai LM, Lewis JB, Kershaw TS, Ethier KA. High postpartum rates of sexually transmitted infections among teens: Pregnancy as a window of opportunity for prevention. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2003;79(6):469–473. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MP, Milardo RM. Network interference in pair relationships: A social psychological recasting of slater theory of social regression. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984;46(4):893–899. doi: 10.2307/352537. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Greenberg LS. The heart of the matter: Perspectives on emotion in marital therapy. New York: Brunner/Mazel Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Arnold A, Gordon D, Magriples U, Niccolai L. In the heart or in the head: Relationship and cognitive influences on sexual risk among young couples. AIDS and Behavior. 2012;16(6):1522–1531. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0049-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Ethier KA, Niccolai LM, Lewis JB, Milan S, Meade C, et al. Let's stay together: Relationship dissolution and sexually transmitted diseases among parenting and non-parenting adolescents. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;33(6):454–465. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw T, Murphy A, Lewis J, Divney A, Albritton T, Magriples U, Gordon D. Family and relationship influences on parenting behaviors of young parents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;54(2):197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Lewis JB, Meade CS, Ethier KA. Short and long-term impact of adolescent pregnancy on postpartum contraceptive use: Implications for prevention of repeat pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33(5):359–368. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00138-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Bornstein MH, Dodge KA, Skinner AT, Putnick DL, Deater-Deckard K. Attributions and attitudes of mothers and fathers in the United States. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2011;11(2–3):199–213. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2011.585567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie LA, Huston TL, Johnson MP. Parental reactions to dating relationships: Do they make a difference. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48(1):57–66. doi: 10.2307/352228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Jones L, Bond MJ, Wright K, Pumpuang M, Maidenberg M, et al. Where is the F in MCH? Father involvement in African American families. Ethnicity & Disease. 2010;20(1):49–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark KP, Janssen E, Milhausen RR. Infidelity in heterosexual couples: Demographic, interpersonal, and personality-related predictors of extradyadic sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(5):971–982. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9771-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale J, Waller MR, Pearson J. Coparenting interventions for Fragile Families: What do we know and where do we need to go next? Family Process. 2012;51(3):284–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR. The intergenerational cycle of teenage motherhood: An ecological approach. Health Psychology. 2008;27(4):419–429. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.4.419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meezan W, Rauch J. Gay marriage, same-sex parenting, and America's children. Future of Children. 2005;15(2):97–115. doi: 10.1353/foc.2005.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milan S, Ickovics JR, Kershaw T, Lewis J, Meade C, Ethier K. Prevalence, course, and predictors of emotional distress in pregnant and parenting adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(2):328–340. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesi JL, Fauber RL, Gordon EA, Heimberg RG. The specific importance of communicating about sex to couples' sexual and overall relationship satisfaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2011;28(5):591–609. doi: 10.1177/0265407510386833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niccolai LM, Ethier KA, Kershaw TS, Lewis JB, Ickovics JR. Pregnant adolescents at risk: Sexual behaviors and sexually transmitted disease prevalence. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188(1):63–70. doi: 10.1067/Mob.2003.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett. Qualitative methods in social work research: Challenges and rewards. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro MF, Ribeiro T, Shelton KH. Marital satisfaction and partners' parenting practices: The mediating role of coparenting behavior. Journal of Family Psychology. 2012;26(4):509–522. doi: 10.1037/a0029121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petch J, Halford WK, Creedy DK, Gamble J. Couple relationship education at the transition to parenthood: A window of opportunity to reach high-risk couples. Family Process. 2012;51(4):498–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2012.01420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhein LM, Ginsburg KR, Schwarz DF, Pinto-Martin JA, Zhao H, Morgan AP, et al. Teen father participation in child rearing: Family perspectives. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1997;21(4):244–252. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(97)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan RM, Tolani N, Brooks-Gunn J. Relationship trajectories, parenting stress, and unwed mothers' transition to a new baby. Parenting-Science and Practice. 2009;9(1–2):160–177. doi: 10.1080/15295190802656844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Barrett AE. Nonmarital romantic relationships and mental health in early adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(2):168–182. doi: 10.1177/0022146510372343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipsma H, Biello KB, Cole-Lewis H, Kershaw T. Like father, like son: The intergenerational cycle of adolescent fatherhood. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):517–524. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.177600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wayland J, Rawlins R. African American teen mothers' perceptions of parenting. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 1997;12(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0882-5963(97)80017-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilde JL, Doherty WJ. Outcomes of an intensive couple relationship education program with fragile families. Family Process. 2013;52(3):455–464. doi: 10.1111/famp.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood RG, Moore Q, Clarkwest A, Killewald A, Monahan S. The long-term effects of building strong families: A relationship skills education program for unmarried parents. Princeton, NJ: The Building Strong Families Project; 2012. [Google Scholar]