Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) play a crucial role in the regulation of gene expression through remodeling of chromatin structures. However, the molecular mechanisms involved in this event remain unknown. In this study, we sought to examine whether HDAC inhibition-mediated protective effects involved HDAC4 sumoylation, degradation, and the proteasome pathway. Isolated neonatal mouse ventricular myocytes (NMVM) and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts were subjected to 48 h of hypoxia (H) (1% O2) and 2 h of reoxygenation (R). Treatment of cardiomyocytes with trichostatin A (TSA) attenuated H/R-elicited injury, as indicated by a reduction of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) leakage, an increase in cell viability, and decrease in apoptotic positive cardiomyocytes. MG132, a potent proteasome pathway inhibitor, abrogated TSA-induced protective effects, which was associated with the accumulation of ubiquitinated HDAC4.NMVMtransduced with adenoviral HDAC4 led to an exaggeration of H/R-induced injury. TSA treatment resulted in a decrease in HDAC4 in cardiomyocytes infected with adenoviral HDAC4, and HDAC4-induced injury was attenuated by TSA. HDAC inhibition resulted in a significant reduction in reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R, which was attenuated by blockade of the proteasome pathway. Cardiomyoblasts carrying wild type and sumoylation mutation (K559R) were established to examine effects of HDAC4 sumoylation and ubiquitination on H/R injury. Disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation brought about HDAC4 accumulation and impairment of HDAC4 ubiquitination in association with enhanced susceptibility of cardiomyoblasts to H/R. Taken together, these results demonstrated that HDAC inhibition stimulates proteasome dependent degradation of HDAC4, which is associated with HDAC4 sumoylation to induce these protective effects.

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are enzymes that affect gene expression through its influence on chromatin-modification by controlling the acetylation of the core histones. The acetylation and deacetylation of histones play a significant role in the regulation of gene transcription in many cell types. Histone acetylation is mediated by histone acetyl transferase. The resulting modification in the structure of chromatin leads to nucleosomal relaxation and altered transcriptional activation. The reverse reaction is mediated by histone deacetylase, which induces deacetylation, chromatin condensation, and transcriptional repression. (Kuo and Allis, 1998; Wang et al., 2014)

Since the identification of HDAC 1 (named HD 1) (Hassig et al., 1998), 18 HDACs have been described in mammals and are divided into three distinct classes based on their primary homology to three Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Verdin et al., 2003). Class IHDACs consist of HDACs 1, 2, 3, and 8, which are predominantly nuclear proteins and ubiquitously expressed. Class II HDACs are further divided into two subclasses, including IIa (HDACs 4, 5, 7 and 9) and IIb (HDACs 6 and 10). HDAC4 and HDAC5 are found at high levels in the heart, brain, and skeletal muscles (Fischle et al., 1999; Grozinger et al., 1999; Wang et al., 1999). Class III HDACs were identified on the basis of sequence similarity with Sir, a yeast transcriptional repressor that requires the cofactor NDA+ for its deacetylase activity. HDAC inhibitors have shown efficacy as anti-cancer reagents in preclinical studies and clinical trials and are emerging as an exciting strategy for targeting cancer (Vigushin and Coombes, 2004; West and Johnstone, 2014).

Recent evidences have revealed the important role of HDACs in cardiac hypertrophy and skeletal myogenesi (Antos et al., 2003; Kee et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2006; Granger et al., 2008; Haberland et al., 2009). Our observations established that HDAC inhibition functions as one of the most important approaches to preventing myocardial injury (Zhao et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2010; Zhang, et al., 2012a; Zhang, et al., 2012b; Zhao et al., 2013). Treatment involving HDAC inhibitors has currently been approved to be a promising clinical anticancer approach (Butler et al., 2002; Komatsu et al., 2006). Pharmacological inhibition of HDACs induced endogenous myocardial regeneration via enhanced cardiac stem cell proliferation and differentiation in the heart (Zhang, et al., 2012a; Zhang, et al., 2012b). HDAC4 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation are regulated by phosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK3β) (Cernotta et al., 2011). Likewise, HDAC4 was found to be recognized by SUMO-1 at a single lysine residue (lysine559) that is modified by SUMO-2 chains in vivo (Tatham et al., 2001). We have recently demonstrated that HDAC inhibition increased the resistance of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in response to oxidant stress and promoted cardiogenesis through a proteasome-dependent pathway (Chen et al., 2011). However, whether HDAC inhibition elicits post-modification of specific HDACs to facilitate protective effects is not investigated. In the present study, we use isolated neonatal mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts to gain insight into the mechanisms by which HDAC inhibition induces protective effects through HDAC4 ubiquitination and sumoylation. Our study demonstrated that HDAC inhibition activates ubiquitination-dependent proteasomal degradation of HDAC4 through sumoylation to achieve cellular protection.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and antibodies

Trichostatin A, MG132, G418, poly-L-Lysine, polyclonal rabbit ubiquitin, α-sarcomeric actinin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, MO). 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) was obtained from Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). Primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies including HDAC1, HDAC3, HDAC4, HDAC6, caspase 3, β-actin were obtained from Cell Signaling Tm (Beverly, MA). HDAC10, glutathione (GSH), superoxide dismutases (SOD 1), polyclonal SUMO-1 primary antibody were obtained from Santa Cruz biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Micro BCA protein assay kit and SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL). Adenoviral-HDAC4 and adenoviral-GFP were purchased from Vector BioLabs, Inc (Philadelphia, PA).

Neonatal cardiomyocytes isolation and cell culture

All animal procedures were approved by the IACUC in accordance with NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals. Neonatal mouse ventricular cardiomyocytes were isolated from 1–3 day old FVB mice using a Worthington neonatal cardiomyocyte isolation system (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Lakewood, NJ) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Ventricles were finely minced and pre-digested with trypsin at 4°C overnight. Further digestion was performed the following day with collagenase IV. Cell suspensions were triturated, filtered, centrifuged, and re-suspended in culture medium. Cells were pre-plated in a T-75 culture dish at 37°C for 1.5 h to deplete the fibroblasts before seeded into culture plates. Cardiomyocytes were plated overnight in medium containing Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 10 mM glutamine. For adenoviral infection, cardiomyocytes were infected with adenoviruses including adenoviral HDAC 4 (ad-HDAC4) or adenoviral GFP (ad-GFP) at multiplicity of infection (MOI) between 10 and 100 (optimized by protein expression level of the transgene) and incubated for 48 h in serum free medium supplemented with 1% ITS (BD Biosciences). Ad-HDAC4, a CMV-driven human HDAC4 (Reference sequence BC039904) was generated from Vector BioLabs, Inc (Catalog 1435, Philadelphia, PA). H9c2 cardiomyoblasts were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). Cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Generation of the stably transfected H9c2 cardiomyoblasts

pcDNA-3.1-HDAC4-wild type (Wt) and pcDNA3.1-HDAC4-K559R plasmids were generous gifts from Dr. Ronald T. Hay (University of St. Andrews, UK). All constructs were confirmed by sequencing. For stable cell lines, H9c2 cardiomyoblasts were transfected with plasmids encoding pcDNA-3.1-HDAC4-wild type and/or pcDNA3.1-HDAC4-K559R plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Forty-eight hours after transfection, G418 (500 µg/ml, EMD Biosciences) was added to the culture medium. Clones were selected after two weeks. Stable transfectants were maintained in regular DMEM medium with G418 containing 100 µg/ml of G418.

Hypoxia/reoxygenation protocol

An in vitro H/R performed according to methodology with modifications (Tong et al., 2013). In brief, when myocytes or cardiomyoblasts grow to approximately 70~80% of confluence, cells were pre-starved using DMEM supplemented with 1% FBS for 2 h then were pretreated with or without MG132 (0.2 µmol/L) for 2 h prior to the administration of TSA. Pharmacologic treatments were then conducted by administration of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) as vehicle and TSA (20 nmol/L) during H/R. Following treatments, cells were subjected to either normoxia or hypoxia in a hypoxic chamber filled with low O2 gas containing 1% O2, 5% CO2 and 94% N2 for 48 h followed by 2 h of reoxygenation. After H/R, cells were harvested for the examination of cell survival, western blot analysis and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Cell viability and cytotoxicity Assay

Following H/R, injury index was assessed by measuring LDH release in the supernatants, which is described in the previous section (Zhao et al., 2010). Following treatments as outlined in the H/R protocol, culture medium was collected and centrifuged, cytotoxicity was determined using a CytoTox 96® non-radioactive cytotoxicity assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The assessment of viabilities of cells was based upon the description and the principle of reduction of 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) into blue formazan pigments in viable cells (Zhao et al., 2010). At the end of the experiment, the medium was removed and the cells washed with PBS. MTT (0.01 g/ml) was dissolved in PBS, and 500 µl of MTT buffer was added to each well. Cells were subsequently incubated for 4 h at 37°C. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and 1 ml of HCl isopropanol Triton (1% HCl in isopropanol; 0.1% Triton X-100; 50:1) was added to each well and incubated for 5 min. The suspension was then centrifuged at 16,000g for 2 min. The optical density was determined spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 550 nm and the values expressed as percentages of normoxia control values.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated dUTP nick end labeling assay (TUNEL)

Cardiomyocytes and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts were grown on coverslips precoated with poly-L-Lysine, (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and then were washed with PBS three times then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 after treatments. Apoptosis was detected with TUNEL labeling using an in situ cell death detection kit from Roche following the manufacturer’s instructions (Tseng et al., 2010). After TUNEL labeling, anti-α-scarcomeric actinin antibody was used to identify cardiomyocytes. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, and the TUNEL positive cells were observed using confocal laser scanning microscopy LSM 700 (Carl Zeiss). The percentages of apoptotic positive cells were determined.

Real time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from H9c2 cardiomyoblasts after treatment with Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). cDNA was synthesized from 5 µg of total RNA. The reverse transcribed cDNA (5 µl) was amplified to a final volume of 50 µl by PCR under standard conditions. Real-time PCR experiments were performed on a mastercycler realplex4 (Eppendorf North America) system using qPCR Kit master mix (Kapabiosystems, Boston). The reaction condition was the following: 95°C for 2 min, then 95°C 15 sec, 60°C 20 sec, 72°C 20 sec for 40 cycles in 20 µl per reaction volume. Primer sequences for HDAC4 used in these studies are as follows: Forward: 5-CTG CAA GTG GCC CCT ACA G-3, Reverse: 5-CTG CTC ATG TTG ACG CTG GA-3. GAPDH was used as the internal control: Forward: 5-ACC ACA GTCCATGCCATCAC-3; Reverse: 5-TCCACCACCCTGTTG CTG TA-3.

Western blot

Cells lysates were harvested in RIPA buffer containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktails. Protein measurement was performed using Micro BCA Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) to determine protein concentration. Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane for 2 h at 100 Volts. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in 1× Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h. The blots were incubated with respective primary antibodies (1:1,000 dilution) for 2 h and visualized by incubation with anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000 dilution) for 1 h. The immunoblots were developed with the ECL chemiluminescence detection reagent (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Pittsburgh, PA). The densitometric measurements were performed to evaluate the protein levels.

Immunoprecipitation

Cells were lysed in cold RIPA buffer at the end of experiments and protein was separated by centrifugation at 4°C. Then protein was incubated with the indicated primary antibodies (HDAC4 or IgG) at 4°C overnight with gentle rotation. On the following day, the EZView Red Protein A affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was pre-washed with cold RIPA buffer three times, beads were then added to lysate plus antibody mix and further incubated for 2 h at 4°C. After incubation, samples were washed with RIPA buffer three times, and proteins were eluted with 4× loading buffer by boiling at 100°C for 5 min and subjected to SDS–PAGE. The resolved proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes, immunoblotted with specific antibodies, and developed with ECL chemiluminescence detection reagent as described above.

Data analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SE. Differences among the groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the Bonferroni correction. A probability of P < 0.05 was considered to be a significant difference.

Results

HDAC inhibition protects cardiomyocytes against Hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) through a proteome dependent pathway

The protective effect of TSA was examined by the determination of cell viabilities in Figure 1A and C. MTT assay demonstrated the marked decrease in cell viability (69 ± 2% in NMVM and 45 ± 3% in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, vs normoxia control, respectively) in response to H/R. However, TSA treatment resulted in a remarkable improvement in cell viability, increasing the survival rate to 96 ± 8% and 85 ± 5% in NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, respectively. As shown in Figure 1B and D, there were significant increases in LDH leakage after H/R compared to normoxia controls in both NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts (190 ± 27% in NMVM and 166 ± 11% in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts vs. normoxia control, respectively). Increased LDH leakage was attenuated by TSA treatment in NMVM (107 ± 10% vs. normoxia control) and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts (128 ± 7% vs. normoxia control), suggesting that inhibition of HDAC protects cardiomyocytes against H/R injury. Furthermore, we used trypan blue staining to assess cell viability in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. As shown in Supplemental Figure 1, there were abundant trypan blue positively stained (35 ± 6%) myocytes observed in response to H/R, but TSA treatment reduced cell death, indicating the prevention of H/R-induced cellular damages induced by HDAC inhibition.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of preoteasome pathway diminishes the protective effects of TSA in NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R). The detailed description of H/R protocol is described in the Methods. A: Cell viabilities of NMVM exposed to H/R; B: LDH release of NMVM exposed to H/R; C: Cell viabilities of H9c2 cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R. D: LDH release of H9c2 cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R; The values represent Mean ± SE of three independent experiments for for H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, and of four independent experiments for cardiomyocytes) *P < 0.001 vs. Normoxia (N); #P < 0.001 vs. hypoxia/reoxygenation (H); +P < 0.001 vs. H/R + TSA; N: normoxia; H/R: hypoxia/reoxygenation; TSA: trichostatin A.

To investigate whether TSA-elicited protective effect in cardiomyocytes is proteasome-dependent, we included MG132, a selective proteasome pathway inhibitor. As shown in Figure 1B and D, treatment of MG132 abolished the reduction of cell death and increase in cell viabilities induced by TSA. In NMVM, LDH leakage increased from 107 ± 10% in TSA to 179 ± 7% in TSA + MG132 (P < 0.05). Likewise, the reduction of LDH leakage in TSA-treated group was also abrogated by MG132 in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts (P < 0.05). On the other hand, MG132 attenuated the cell survival rates induced by TSA in both NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts in response to H/R (P < 0.05) (Figure 1 A, C and Supplemental Figure 1).

HDAC inhibition mitigates HDAC4-inudced detrimental effects via proteasome pathway

In order to examine whether HDAC inhibition attenuates HDAC4-elicited cellular injuries in association with the proteasome pathway, we infected cardiomyoctes with adenoviral-HDAC4. As shown in Figure 2A and B, transduction ofHDAC4 increased LDH leakages and reduced cell viabilities in cardiomyocytes exposed to H/R. TSA treatment diminished the detrimental effects induced by transduction of HDAC4. However, counter-effects of TSA on HDAC4-induced cellular injury in transduced cardiomyocytes were abrogated by MG132 treatment, indicating that HDAC inhibition mitigated HDAC4-induced cellular injury through the proteasome pathway.

Figure 2.

HDAC4 overexpression-induced injury is mediated by the preoteasome pathway in NMVM exposed to H/R. A: Cell viabilities of NMVM transduced with adenoviral HDAC4. B: LDH leakages of NMVM transduced with adenoviral HDAC4. *P < 0.001 vs. N + ad-GFP; #P < 0.001 vs. H/R + ad-GFP; +P 003C; 0.001 vs. H/R + ad-HDAC4; &P < 0.001 vs. H/R + ad-HDAC4 + TSA. Values represent Mean ± SE of three independent experiments; H/R: hypoxia/reoxygenation; N: normoxia; TSA: trichostatin A; ad-HDAC4: adenoviral HDAC4.

Blockade of proteasome pathway attenuates TSA-induced anti-apoptotic effects

The effects of proteasome pathway in association with the anti-apoptotic effect of TSA were estimated in NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. As demonstrated in Figure 3A, C and D, TSA treatment shows the fewer apoptotic nuclei, which was abrogated by MG132. Quantitative analysis demonstrated that there was a significant amount of TUNEL-positive nuclei (43 ± 6% in NMVM, 77 ± 5% in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts) in response to H/R as compared to the normoxic control (N + Vehicle, Figure 3B, E). In TSA-treated group, apoptotic-positive cells were reduced in both NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts (14 ± 2% and 53 ± 2%, respectively, P < 0.05) as compared to the hypoxia/reoxygenation group (H/R + Vehicle). There was no significant difference between TSA + MG132 and H/R groups (H/R + Vehicle). Caspase-3 was examined by western blots to further estimate and confirm apoptosis. As shown in Figure 4 A and B, active caspase-3 was absent in normoxia, but an increase in active caspase-3 was observed in response to H/R. TSA treatment reduced active caspase-3 signals. However, the pretreatment of cells with MG132 mitigated TSA-induced reduction of the cleaved caspase-3.

Figure 3.

Blockade of proteasome pathway attenuates anti-apoptotic effect of TSA in NMVM and H9c2 cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R. Representative images of TUNEL staining of NMVM in A; Blue: DAPI labeled nuclei; Green: FITC-labeled apoptotic nuclei, Red: Cy3 labeled α-sarcomeric actinin, scale bar = 50 µm; B: TUNEL-positive nuclei in NMVM; C: High magnification of stained NMVM, scale bar = 15µm; D: TUNEL-positive nuclei in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, E: Quantification of TUNEL-positive nuclei *P < 0.0001 vs. N + Vehicle; #P < 0.001 vs. H/R + Vehicle; +P < 0.05 vs. H/R + TSA. Values represent Mean ± SE of five independent experiments; H/R: hypoxia/reoxygenation; TSA: trichostatin A.

Figure 4.

Anti-apoptotic effects of TSA are attenuated by MG132 in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R. A: Representative image of Western blot in H9c2 cells; B: Densitometric analysis of active casepase-3; *P < 0.01 vs. N + Vehicle; #P < 0.0001 vs. H/R + Vehicle; +P < 0.001 vs. H/R + TSA. Values represent Mean + SE of four independent experiments; H/R: hypoxia/reoxygenation; N: normoxia; TSA: trichostatin A.

Inhibition of HDACs decreased ROS production and increased anti-oxidant enzymes

Superoxide production in cardiomyobasts was measured in the different treatments. As shown in Supplementary Figure 2A, production of ROS increased significantly in cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R, but the magnitude of ROS release was attenuated following HDAC inhibition. However, HDAC inhibition-induced ROS reduction was abolished by blockade of the proteasome pathway. On the other hand, the contents of GSH and SOD1 were examined. As shown in Supplementary Figures 2B and C, HDAC inhibition remarkably increased both GSH and SOD1 levels in cardiomyoblasts exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation, but the increased GSH and SOD1 levels following HDAC inhibition were attenuated by inhibiting the proteasome pathway.

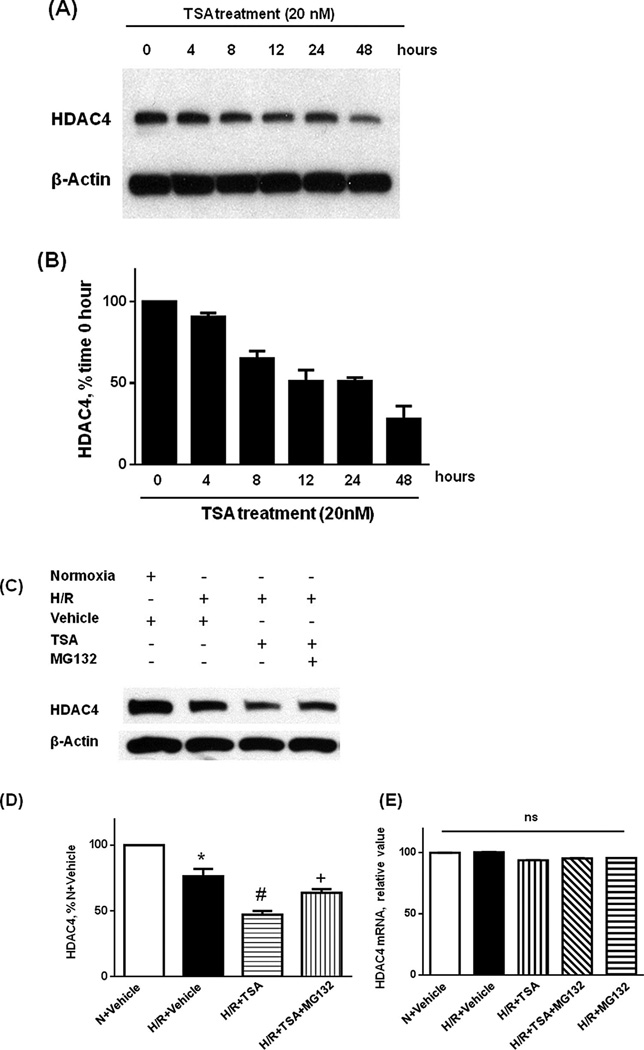

Inhibition of HDAC by TSA promoted HDAC4 degradation

Since we demonstrated that TSA-induced protective effects were mitigated by blockade of the proteasome pathway, we then attempted to determine the effect of TSA on the HDAC4 protein levels. As shown in Figure 5A and B, the time-course analysis demonstrated that TSA treatment resulted in a gradual reduction of HDAC4 protein at 0, 4, 8, 12, 24, and 48 h. HDAC protein expression was further examined in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts in response to H/R. Figure 5C and D confirm that TSA treatment caused the reduction of HDAC4 in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts in response to H/R, whereas administration of MG132 prevented the reduction of HDAC4 caused by TSA. We further analyzed mRNA expression of HDAC4 in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts treated with TSA. Quantitative PCR analysis shows that there was no statistical difference in RNA expression between groups (Figure 5E). We also examined the protein levels of other HDAC isoforms including HDAC1, HDAC3, HDAC6, and HDAC10. As shown in Supplemental Figure 3, the contents of HDAC1, HDAC3, HDAC6, and HDAC10 did not demonstrate detectable changes following TSA treatments. Accordingly, HDAC1, HDAC3, HDAC6, and HDAC10 did not show differences following the cells exposed to inhibition of proteasome pathway (not shown).

Figure 5.

TSA treatment enhances HDAC4 protein degradation. A: Western blot showing HDAC4 degradation in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts; B: Quantification of HDAC4 protein levels following TSA treatment at 0, 4, 8, 12, 24 hours, C: TSA-induced reduction of HDAC4 was attenuated by MG132; D: Quantification of HDAC4 proteins after TSA and MG132 treatments; E: Real time-PCR detection of HDAC4 mRNA after TSA and MG123 treatments. *P < 0.01 vs. N + Vehicle; #P < 0.001 vs. H/R + Vehicle; +P < 0.001 vs. H/R + TSA. Values represent Mean ± SE of three independent experiments; There is no change in HDAC4 mRNA; TSA: trichostatin A.

TSA elicits poly-ubiquitination-mediated HDAC4 degradation

To further determine the mechanisms underlying TSA-induced degradation of HDAC4, an immunoprecipitation assay was performed to examine if HDAC4 reduction was ubiquitination-dependent. The extracts from TSA-treated cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-HDAC4 antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-poly-ubiquitin antibody. Poly-ubiquitinated HDAC4 was observed after TSA treatment. In addition, as shown in Figure 6A and B, TSA treatment led to an increases in poly-ubiquitinated HDAC4 in response to H/R. Blockade of proteasome pathway with MG132 significantly increased the accumulation of ubiquitinated HDAC4. These data suggest that TSA treatment promotes HDAC4 ubiquitination in both normoxia and H/R.

Figure 6.

HDAC inhibition induces HDAC4 ubiquitination and degradation. A: Immunoprecipitation showing that TSA-induced HDAC4 ubiquitination in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts exposed to H/R; B: Densitometric analysis of ubiquitinated HDAC4; #P < 0.001 vs. H/R + Vehicle; +P < 0.001 vs. H/R + TSA. Values represent Mean ± SE of three independent experiments. IP: immunoprecipitation; IB: immunoblot; IgG: Immunoglobulin G.

HDAC4 sumoylation-mediated ubiquitination controls cell survivals

To see whether HDAC4 sumoylation was associated with ubiquitination of HDAC4, we established stable H9c2 cardiomyoblasts expressing wild-type HDAC4 and/or HDAC4-(K559R)SUMO mutant. As shown in Figure 7A and B, the immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated less ubiquitinated-HDAC4 in the cells with disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation as compared to the cells transfected with wild type HDAC4, suggesting a direct correlation of HDAC4 sumoylation with ubiquitination. To further detect the role of HDAC4 sumoylation in the regulation of hypoxic response, we analyzed cell viabilities and cyototocixity in HDAC4 sumolyation-mutant H9c2 cardiomyoblasts. As shown in Figure 8, disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation further reduced the cell viability (Figure 8A) and augmented LDH leakage (Figure 8B). Treatment of cells with TSA attenuated increased LDH level in wild type group, but not in HDAC4 sumoylation-mutant H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, suggesting that HDAC4 sumoylation is closely related to TSA-induced survival. Figure 9 showed that TSA treatment induced a reduction of HDAC4 accumulation in the cytosol, but disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation attenuated the effects of TSA on cytosolic HDAC4, suggesting that sumoylation of HDAC4 may modulate the subcelluar distribution of HDAC4.

Figure 7.

Disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation attenuates HDAC4 ubiquitination. A: HDAC4 ubiquitination and degradation in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts, which express empty vector, wild type HDAC4 and HDAC4 K599R, respectively; B: Densitometric analysis of ubiquitinated HDAC4. *P < 0.01 vs. pcDNA-3; &P < 0.01 vs. HDAC4-WT. Values represent Mean ± SE of three independent experiments. IP: immunoprecipitation; IB: immunoblot; IgG: Immunoglobulin G; WT: wild type.

Figure 8.

Disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation attenuates TSA-elicited protective effect against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury. A: Cell viabilities (MTT) in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts expressing both WT and mutant HDAC4 exposed to H/R. B: Cell cytotoxicity in H9c2 cardiomyoblasts expressing both WT and mutant HDAC4 exposed to H/R. *P < 0.05 vs. N + pcDNA3; #P < 0.05 vs. H/R + pcDNA3; &P < 0.01 vs. N + pcDNA3; %P < 0.001 vs. H/R + HDAC4-WT. Values represents Mean ± SE of three independent experiments. N: normoxia; H/R: hypoxia/reoxygenation; TSA: trichostatin A; WT: wild type.

Figure 9.

Inhibition of the proteasome pathway attenuates TSA-induced reduction of cytosolic HDAC4. H9c2 cardiomyoblasts expressing wild type HDAC4 and/or HDAC4 K599R were stimulated with TSA as described in the Methods. The accumulation of HDAC4 in nuclei and cytosol was examined. Red: HDAC4-cMyc, Blue: DAPI. Scale bar: 20 µm.

Discussion

Salient findings

In this study, we demonstrated that: (1) HDAC inhibition increased the resistance of cardiomyocytes in response to H/R, as evidenced by an increased cell survival and reduction of cytotoxicity, and an anti-apoptotic effect; (2) The protective effect of HDAC inhibition was attenuated by the proteasome inhibitor MG132, suggesting that TSA-elicited beneficial effects against H/R were associated with the proteasomal pathway; (3) HDAC4 overexpression dramatically increased cell death and reduced cell viabilities in response to H/R, and TSA ameliorated the deleterious effects of HDAC4 in association with TSA-induced reduction of HDAC4; (4) TSA treatment resulted in a significant increase in poly-ubiquitinated HDAC4 and subsequent HDAC4 degradation; (5) disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation increases the susceptibility of cardiomyocytes to H/R injury. HDAC4 ubiquitination is reduced with disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation; and (6) HDAC inhibition attenuated the production of ROS in cardiomyoblasts exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation, which was mitigated by inhibition of proteasome pathway. Taken together, these results indicate that trichostatin A effectively elicits HDAC4 ubiquitination, which plays a critical role in the modulation of cell survivals.

HDAC inhibitors were extensively tested in many disease models to achieve their therapeutic effects. Our previous works and other observations have demonstrated that HDAC inhibitors elicited cardioprotective effects against cellular and myocardial ischemic injuries (Chen et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2007; Zhang et al. 2012a; Zhang et al., 2012b; Zhao et al., 2010; Zhao et al., 2013). In addition to cardioprotective effects on ischemic hearts, HDAC inhibitors have also exerted anti-hypertrophic effects in the hearts and other disease models (Antos et al., 2003; Hockly et al., 2003; Kee et al., 2006; Kong et al., 2006; Granger et al., 2008; Haberland et al., 2009; Marks, 2010). However, the role of specific HDAC isoforms and downstream signaling pathway following HDAC inhibition remain unclear. We observed that TSA reduced the cell death rate, showed an anti-apoptotic effect, and increased cell viabilities in myocytes in H/R. The protective effect was eliminated by MG132, indicating the involvement of the proteaosomal pathway in mediating TSA-induced beneficial effects. Although nutrition was not removed in our studies, we found that nutrition-starvation by itself in the absence of H/R could not affect cell survival as well as the content of HDAC4 protein (Supplemental Figure 4), suggesting that the presence of nutrition may not serve as the determinant factor for cell deaths and survival in our studies. However, nutrition starvation could exacerbate cellular injuries in cells exposed to H/R in relative to cells cultured with normal condition (data not shown). In addition, our data indicate that HDAC inhibition reduced the production of ROS in cardiomyoblasts exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation, which is associated with increases in anti-oxidant enzymes. The enhanced anti-oxidant capacity by HDAC inhibition is also dependent on the proteasome pathway. In line with our funding, our previous works indicated that HDAC4 was up-regulated in response to oxidant stress and genetic inhibition of HDAC4 promoted myocardial regeneration (Chen et al., 2011), implying that HDAC4 may function as a critical HDAC isoform attributable for cardioprotection and repairs. Overexpression of HDAC4 increased hypoxic-induced cell damage in NMVM, addressing the importance of HDAC4 in determining cell survivals in response to stress. TSA antagonized the detrimental effect of HDAC4 in association with the reduction of HDAC4 proteins, but not other HDACs including HDAC1, 3, 6 and 10, pointing out that TSA-elicited protection is closely related to HDAC4 reduction. In addition, the present study demonstrates that HDAC4 decreased in cardiomyocytes exposed to hypoxia/reoxygenation, which may suggest that the decrease in HDAC4 acts as a natural protection against cell death triggered by H/R.

To further define whether HDAC4 ubiquitination was attributed to TSA-induced HDAC4 protein reduction, we examined whether TSA could lead to initiation of HDAC4 ubiquitination. We found that the ubiquitinated HDAC4 was elevated following TSA treatment, suggesting that HDAC4 ubiquitination is associated with HDAC4 reduction. Although HDAC4 ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation are reported from the earlier observation; however, the mechanism of HDAC4 ubiquitination still remains to be clarified (Butler et al., 2002).

SUMO (small ubiquitin-like modifier) modification is the covalent attachment of SUMO to lysine residues. Analogous to ubiquination, the conjugation of SUMO proteins to lysines of targets substrates plays a critical role in modulating the activity and degradation of targeted proteins (Hannoun et al., 2010; Woo and Abe, 2010; Yeh, 2009). HDAC4 was found to be recognized by SUMO-1 at a single lysine residue (lysine559). However, HDAC4 at lysine 559 mutation displayed significantly impaired transcriptional repression and enzymatic activities relative to the wild-type HDAC4 protein (Tatham et al., 2001). Our observation showed an increase in sumoylation of HDAC4 following TSA treatment. Disruption of HDAC4 specific sumoylation at lysine 559 demonstrated an impairment of HDAC4 ubiqutination and accumulation of HDAC4 proteins, revealing that HDAC4 sumoylation mediates the ubiqutination and subsequent degradation of HDAC4. Furthermore, disruption of HDAC4 sumoylation augmented the hypoxic injury and abolished TSA-generated protective effects, suggesting HDAC4 sumoylation is critical for TSA-mediated HDAC4 ubiquitinaiton and protective effects.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that HDAC inhibition prevents cell death, increases cell survivals, and reduces the production of ROS and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes exposed to H/R. The protection against H/R was attenuated by MG132, suggesting the involvement of proteasomal pathway in this event. Pretreatment of cardiomyocytes with TSA resulted in the ubiquitination of HDAC4 and subsequent HDAC4 degradation. Overexpression of HDAC4 increased the susceptibility of cardiomyocytes to hypoxic injury. TSA treatments led to the reduction of HDAC4 and attenuated HDAC4-induced hypoxic injury. Furthermore, sumoylation of HDAC4 was increased following HDAC inhibition and was associated with HDAC4 ubiquitination. Disruption of sumoylation of HDAC4 diminished HDAC4 ubiqutination and attenuated HDAC inhibition-induced protective effects. Taken together, this is the first study to reveal that TSA produces protective effects through the proteasome pathway and HDAC4 ubiquitination. Our study also provides evidence that HDAC4 sumoylation plays a crucial role in mediating HDAC ubiquitination and brings protective effects. The studies provide new insight into understanding the molecular mechanism of HDAC inhibition and hold promise in developing specific HDAC inhibitors as new therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Contract grant sponsor: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute;

Contract grant number: R01 HL089405 and R01 HL115265.

Footnotes

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

Literature Cited

- Antos CL, McKinsey TA, Dreitz M, Hollingsworth LM, Zhang CL, Schreiber K, Rindt H, Gorczynski RJ, Olson EN. Dose-dependent blockade to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by histone deacetylase inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:28930–28937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler LM, Zhou X, Xu WS, Scher HI, Rifkind RA, Marks PA, Richon VM. The histone deacetylase inhibitor SAHA arrests cancer cell growth, up-regulates thioredoxin-binding protein-2, and down-regulates thioredoxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11700–11705. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182372299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernotta N, Clocchiatti A, Florean C, Brancolini C. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of HDAC4, a new regulator of random cell motility. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:278–289. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-07-0616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HP, Denicola M, Qin X, Zhao Y, Zhang L, Long XL, Zhuang S, Liu PY, Zhao TC. HDAC inhibition promotes cardiogenesis and the survival of embryonic stem cells through proteasome-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;112:3246–3255. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle W, Emiliani S, Hendzel MJ, Nagase T, Nomura N, Voelter W, Verdin E. A New Family of Human Histone Deacetylases Related to Saccharomyces cerevisiae HDA1p. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11713–11720. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger A, Abdullah I, Huebner F, Stout A, Wang T, Huebner T, Epstein JA, Gruber PJ. Histone deacetylase inhibition reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. FASEB J. 2008;22:3549–3560. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozinger CM, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Three proteins define a class of human histone deacetylases related to yeast Hda1p. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4868–4873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberland M, Montgomery RL, Olson EN. The many roles of histone deacetylases in development and physiology: implications for disease and therapy. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:32–42. doi: 10.1038/nrg2485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannoun Z, Greenhough S, Jaffray E, Hay RT, Hay DC. Post-translational modification by SUMO. Toxicology. 2010;278:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassig CA, Tong JK, Fleischer TC, Owa T, Grable PG, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL. A role for histone deacetylase activity in HDAC1-mediated transcriptional repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3519–3524. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockly E, Richon VM, Woodman B, Smith DL, Zhou X, Rosa E, Sathasivam K, Ghazi-Noori S, Mahal A, Lowden PA, Steffan JS, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lewis CM, Marks PA, Bates GP. Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, ameliorates motor deficits in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:2041–2046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437870100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kee HJ, Sohn IS, Nam KIl, Park JE, Qian YR, Yin Z, Ahn Y, Jeong MH, Bang YJ, Kim N, Kim JK, Kim KK, Epstein JA, Kook H. Inhibition of histone deacetylation blocks cardiac hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II infusion and aortic banding. Circulation. 2006;113:51–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.559724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Kawamata N, Takeuchi S, Yin D, Chien W, Miller CW, Koeffler HP. SAHA, a HDAC inhibitor, has profound anti-growth activity against non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2006;15:187–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong Y, Tannous P, Lu G, Berenji K, Rothermel BA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Suppression of class I and II histone deacetylases blunts pressure-overload cardiac hypertrophy. Circulation. 2006;113:2579–2588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.625467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo MH, Allis CD. Roles of histone acetyltransferases and deacetylases in gene regulation. Bioessays. 1998;20:615–626. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199808)20:8<615::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks PA. The clinical development of histone deacetylase inhibitors as targeted anticancer drugs. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19:1049–1066. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.510514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham MH, Jaffray E, Vaughan OA, Desterro JM, Botting CH, Naismith JH, Hay RT. Polymeric chains of SUMO-2 and SUMO-3 are conjugated to protein substrates by SAE1/SAE2 and Ubc9. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35368–35374. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104214200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong W, Xiong F, Li Y, Zhang L. Hypoxia inhibits cardiomyocyte proliferation in fetal rat hearts via upregulating TIMP-4. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R613–R620. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00515.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng A, Stabila J, McGonnigal B, Yano N, Yang MJ, Tseng YT, Davol PA, Lum LG, Padbury JF, Zhao TC. Effect of disruption of Akt-1 of lin(?) c-kit(+) stem cells on myocardial performance in infarcted heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;87:704–712. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin E, Dequiedt F, Kasler HG. Class II histone deacetylases: versatile regulators. Trends Genet. 2003;19:286–293. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigushin DM, Coombes RC. Targeted histone deacetylase inhibition for cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2004;4:205–218. doi: 10.2174/1568009043481560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AH, Bertos NR, Vezmar M, Pelletier N, Crosato M, Heng HH, Th’ng J, Han J, Yang XJ. HDAC4, a human histone deacetylase related to yeast HDA1, is a transcriptional corepressor. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7816–7827. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Qin G, Zhao TC. HDAC4: mechanism of regulation and biological functions. Epigenomics. 2014;6:139–150. doi: 10.2217/epi.13.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West AC, Johnstone RW. New and emerging HDAC inhibitors for cancer treatment. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:30–39. doi: 10.1172/JCI69738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo CH, Abe J. SUMO–a post-translational modification with therapeutic potential? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:146–155. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh ET. SUMOylation and De-SUMOylation: wrestling with life’s processes. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:8223–8227. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LX, Zhao Y, Cheng G, Guo TL, Chin YE, Liu PY, Zhao TC. Targeted deletion of NF-kappaB p50 diminishes the cardioprotection of histone deacetylase inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H2154–H2163. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01015.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Chen B, Zhao Y, Dubielecka PM, Wei L, Qin GJ, Chin YE, Wang Y, Zhao TC. Inhibition of histone deacetylase-induced myocardial repair is mediated by c-kit in infarcted hearts. J Biol Chem. 2012a;287:39338–39348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.379115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Xin Q, Zhao Y, Fast L, Zhuang S, Liu P, Cheng G, Zhao TC. Inhibition of histone deacetylases preserves myocardial performance and prevents cardiac remodeling through stimulation of endogenous angiomyogenesis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012b;341:285–293. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.189910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao TC, Cheng G, Zhang LX, Tseng YT, Padbury JF. Inhibition of histone deacetylases triggers pharmacologic preconditioning effects against myocardial ischemic injury. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;76:473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao TC, Zhang LX, Cheng G, Liu JT. Gp-91 mediates histone deacetylase inhibition-induced cardioprotection. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:872–880. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao TC, Du J, Zhuang S, Liu P, Zhang LX. HDAC inhibition elicits myocardial protective effect through modulation of MKK3/Akt-1. PloS ONE. 2013;8:e65474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.