Abstract

Coenzyme Q (Q or ubiquinone) is a redox-active polyisoprenylated benzoquinone lipid essential for electron and proton transport in the mitochondrial respiratory chain. The aromatic ring 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HB) is commonly depicted as the sole aromatic ring precursor in Q biosynthesis despite the recent finding that para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) also serves as a ring precursor in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Q biosynthesis. In this study, we employed aromatic 13C6-ring-labeled compounds including 13C6-4HB, 13C6-pABA, 13C6-resveratrol, and 13C6-coumarate to investigate the role of these small molecules as aromatic ring precursors in Q biosynthesis in Escherichia coli, S. cerevisiae, and human and mouse cells. In contrast to S. cerevisiae, neither E. coli nor the mammalian cells tested were able to form 13C6-Q when cultured in the presence of 13C6-pABA. However, E. coli cells treated with 13C6-pABA generated 13C6-ring-labeled forms of 3-octaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid, 2-octaprenyl-aniline, and 3-octaprenyl-2-aminophenol, suggesting UbiA, UbiD, UbiX, and UbiI are capable of using pABA or pABA-derived intermediates as substrates. E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and human and mouse cells cultured in the presence of 13C6-resveratrol or 13C6-coumarate were able to synthesize 13C6-Q. Future evaluation of the physiological and pharmacological responses to dietary polyphenols should consider their metabolism to Q.

Keywords: antioxidants, isoprenoids, lipids/chemistry, mass spectrometry, mitochondria, ubiquinone, plant polyphenols, stilbene

Coenzyme Q (Q or ubiquinone) is a polyisoprenylated benzoquinone lipid essential for electron and proton transport in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and in the plasma membrane of Escherichia coli (1, 2). The hydroquinone or reduced form [coenzyme QH2 or ubiquinol (QH2)] functions as a chain-terminating lipid antioxidant and as a coantioxidant to recycle vitamin E (3). Q is also involved in many other metabolic processes, including fatty acid β-oxidation, sulfide oxidization, disulfide bond formation, and pyrimidine metabolism (4–7). Q is composed of a fully substituted benzoquinone ring that is attached to a polyisoprenyl tail with a variable number of isoprenyl units (six for Saccharomyces cerevisiae, eight for E. coli, nine for mouse, and ten for human, hence Q10).

Most cells rely on de novo synthesis for sufficient amounts of Q, although brown adipose tissue was recently discovered to rely on uptake of exogenously supplied Q (8). In baker’s yeast, S. cerevisiae, at least 13 gene products, Coq1-Coq11, Arh1, and Yah1 (9–14) are essential for Q biosynthesis. The Coq1 polypeptide synthesizes the polyisoprenyl tail and Coq2 attaches the tail to the aromatic ring (Fig. 1). The other Coq polypeptides catalyze ring modifications including O-methylation (Coq3), C-methylation (Coq5), hydroxylation (Coq6 and Coq7), and the function of Coq6 requires ferredoxin (Yah1) and ferredoxin reductase (Arh1) (9). The roles of Coq4, Coq8, Coq9, Coq10, and Coq11 have not yet been determined, although they are all required for efficient yeast Q biosynthesis. Schemes of Q biosynthesis generally depict 4-hydroxybenzoic acid (4HB) as the biosynthetic aromatic ring precursor of Q (4). 4HB is considered to derive from chorismate in yeast and from phenylalanine or tyrosine in animal cells (15–17). Yeast can also use para-aminobenzoic acid (pABA) as an alternate ring precursor in the biosynthesis of Q (9, 18). This finding was surprising because pABA is a well-known precursor of folate, which is synthesized de novo by many microorganisms and folate is a vitamin for humans. A biosynthetic scheme was reported recently including proposed steps for the conversion of pABA to Q6 in S. cerevisiae (19).

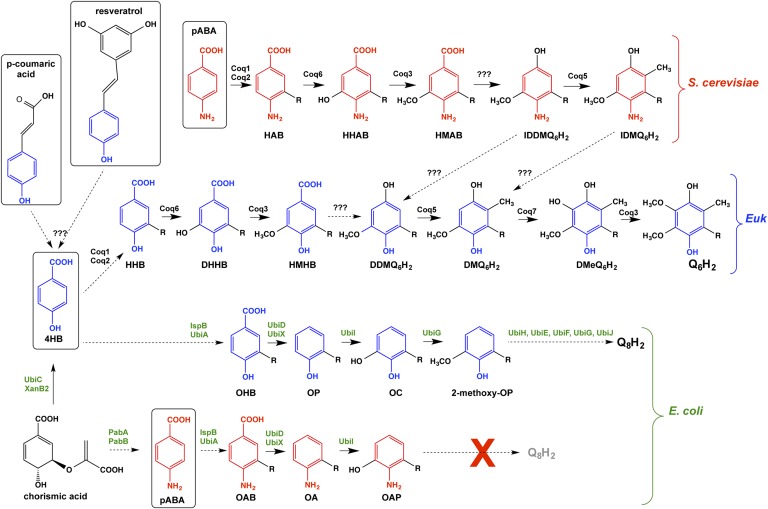

Fig. 1.

Schemes of Q biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae, other eukaryotes, and E. coli. In S. cerevisiae, Coq1 synthesizes the hexaprenyl diphosphate tail, and Coq2 adds the hexaprenyl tail (denoted as “R”) to either 4HB or to pABA, forming 3-hexaprenyl-4HB (HHB) or 3-hexaprenyl 4-aminobenzoic acid (HAB). Coq6 adds the first hydroxyl group to the C5 position of the aromatic ring, forming either 3-hexaprenyl-4,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHHB) or 3-hexaprenyl-5-hydroxy-4-aminobenzoic acid (HHAB). An undetermined enzyme catalyzes the decarboxylation step, forming demethyl-demethoxy Q6 (DDMQ6) or imino-demethyl-demethoxy-Q6 (IDDMQ6). Coq5 catalyzes the C-methylation at the C2 position of the aromatic ring, producing either demethoxy-Q6 (DMQ6) or imino-demethoxy-Q6 (IDMQ6). The 4HB and pABA branches are proposed to converge at the steps designated by the dotted arrows. Coq7 adds the second OH group to the C6 position, generating demethyl-Q6 (DmeQ6), followed by the second O-methylation catalyzed by Coq3 to synthesize Q6. Coq4, Coq9, Coq10, and Coq11 are required for efficient Q6 biosynthesis, but their function is yet to be determined. Human and mouse cells (depicted as “Euk”) produce Q10 and Q9 via steps similar to those shown for S. cerevisiae. E. coli proteins responsible for Q8 biosynthesis are designated with green text. UbiC converts chorismate to 4HB. IspB synthesizes the octaprenyl diphosphate tail and UbiA adds the octaprenyl tail (denoted as “R”) to the 4HB or pABA to form 3-octaprenyl-4HB (OHB) or OAB. UbiD and/or UbiX catalyze the decarboxylation of the aromatic ring forming OP or OA. UbiI adds the first hydroxyl to the ring to form octaprenylcatechol (OC) or 2-amino-3-octaprenylphenol (OAP). The pABA branch of the pathway stops at this step, while UbiG O-methylates OC to form 2-methoxy-OP. Additional ring modifications catalyzed by UbiH, UbiE, UbiF, and UbiG form the final product Q8H2. UbiB and UbiJ are required for Q8 biosynthesis, but their function is yet to be determined. Boxed compounds designate the aromatic ring precursors tested in this study.

The biosynthesis of Q8 in E. coli requires IspB (which synthesizes the octaprenyl diphosphate tail precursor) (20) and 11 Ubi polypeptides (UbiA–UbiJ and UbiX; Fig. 1) (21). UbiC carries out the first committed step in the biosynthesis of Q8, the conversion of chorismate to 4HB (22). UbiA adds the octaprenyl tail to the 4HB ring, followed by the decarboxylation catalyzed by UbiD and UbiX. UbiI adds the first hydroxyl group at the C5 position, followed by O-methylation catalyzed by UbiG, the homolog of yeast Coq3. Additional ring modifications catalyzed by UbiH, UbiE, UbiF, and UbiG generate the final product of Q8. UbiB, an atypical protein kinase similar to Coq8, and UbiJ play essential, but unknown, functions in E. coli Q8 biosynthesis (21).

Recently, Block et al. (15) identified para-coumarate (p-coumarate) as a ring precursor of Q biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Arabidopsis converts phenylalanine to p-coumarate in the cytosol, and following transport into peroxisome, p-coumarate is ligated to CoA and the three-carbon side chain is shortened via peroxisomal β-oxidation (15). Plant peroxisomes appear to contain thiolases and CoA thioesterases that can ultimately produce 4HB from 4-hydroxybenzoyl-CoA (15). Tyrosine can also supply the ring of Q in Arabidopsis; but this must occur via a nonintersecting pathway, because Arabidopsis mutants unable to utilize phenylalanine still utilized tyrosine as a ring precursor of Q (15). Animal cells are able to hydroxylate phenylalanine to form tyrosine, and it is presumed that conversion of tyrosine to 4HB occurs via its metabolism to p-coumarate (16, 23). However, the enzymes involved in 4HB biosynthesis in either yeast or animal cells have not been identified.

The in vivo metabolism of potential ring precursors labeled with the stable isotope 13C can be determined with high sensitivity and specificity with reverse phase (RP)-HPLC-MS/MS identification and quantification. Using this approach, Block et al. (15) showed that Arabidopsis was not able to incorporate 13C6-pABA into Q. Here, we have made use of 13C6-ring-labeled forms of pABA and p-coumarate to track their metabolic fate as potential Q biosynthetic precursors in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and animal cells. Due to its structural similarity with p-coumarate, 13C6-resveratrol was also tested as a ring precursor in Q biosynthesis. In this study, we found that human and E. coli cells do not utilize pABA as an aromatic ring precursor in the synthesis of Q, while resveratrol and p-coumarate serve as ring precursors of Q in E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and human cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast growth and stable isotope labeling

The S. cerevisiae strains used are described in Table 1. YPD medium (2% glucose, 1% yeast extract, 2% peptone) was prepared as described (24). Solid plate medium included the stated components plus 2% Bacto agar. Yeast colonies from YPD plate medium were first inoculated into 250 ml flasks containing 70 ml YPD liquid medium. Following overnight incubation with shaking (250 rpm) at 30°C, yeast cells were transferred into fresh drop out dextrose (DoD) medium (18). DoD medium contained 2% dextrose, 6.8 g/l Bio101 yeast nitrogen base minus pABA minus folate with ammonium sulfate (MP Biomedicals), and 5.83 mM sodium monophosphate (pH adjusted to 6.0 with NaOH). Amino acids and nucleotides were added as described previously (18).

TABLE 1.

Genotype and source of S. cerevisiae and E. coli strains

| Strain | Genotype | Source |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| W3031B | MAT α ade2-1 his3-1,15 leu2-3,112 trp1-1 ura3-1 | R. Rothsteina |

| BY4741 | MAT a his3Δ0 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | Open Biosystems |

| E. coli | ||

| HW272 | ubiG+ zei::TnlOdTet | (52) |

| BW25113 | rrnB3 ΔlacZ4787 hsdR514 Δ(araBAD)567 Δ(rhaBAD)568 rph-1 | (27) |

| BW25113ubiC | rrnB3 ΔlacZ4787 hsdR514 Δ(araBAD)567 Δ(rhaBAD)568 rph-1 ΔubiC::kan | (27) |

| MG1655 | F− lambda− ilvG− rfb-50 rph-1 | (53) |

| MG1655ubiC | MG1655+P1/JW5713 (10), selection LB kan | F. Pierrelb |

Dr. Rodney Rothstein, Department of Human Genetics, Columbia University.

Dr. Fabien Pierrel, Laboratoire de Chimie et Biologie des Métaux, Université Grenoble.

Stable isotope-containing compounds included p-hydroxy[aromatic-13C6]benzoic acid ([13C6]4HB) from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Andover, MA); resveratrol[4-hydroxyphenyl-13C6] ([13C6]resveratrol), and p-amino[aromatic-13C6]benzoic acid ([13C6]pABA) from Sigma/ISOTEC (Miamisburg, OH). During this work, we discovered that preparations of [13C6]pABA supplied by Cambridge Isotope Laboratories were contaminated with approximately 1% [13C6]4HB. This small level of contamination confounded the initial labeling studies we performed. All studies reported here were performed with the [13C6]pABA obtained from Sigma/ISOTEC, and there was no detectable contamination with [13C6]4HB present in either the [13C6]pABA or [13C6]resveratrol (data not shown).

13C6-labeled aromatic ring precursors were added to fresh DoD medium and incubated with yeast cells (100 A600) at 30°C for 4 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation and pellets were stored at −20°C. The wet weight of each cell pellet was determined by subtracting the weight of the tube from the total weight. Protein assays (BCA assay, Thermo) were performed on yeast cell lysates (25). For 13C6-coumarate labeling, BY4741 yeast cells were incubated in 5 ml of SD-complete medium at a starting cell density of 0.1 A600 and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. The yeast cell density after incubation was approximately 6 A600.

Synthesis of p-coumaric acid [aromatic-13C6]

The synthesis was similar to the method described by Robbins and Schmidt (26), with the following modifications. To a flame-dried flask (25 ml) was added 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde [aromatic-13C6] (50 mg), malonic acid (75 mg), piperidine (5 μl), and pyridine (1 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred under argon at 92°C. The reaction was monitored through thin layer chromatography on 0.25 mm SiliCycle silica gel plates and visualized under UV light and with permanganate or 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine staining. Upon completion (12 h), the mixture was sequentially added to 10 ml water, neutralized to pH 7–8, and then washed with dichloromethane. The aqueous solution was acidified to pH 1 and then extracted twice using ethyl acetate. The combined organic extract was concentrated in vacuo and purified through flash column chromatography. Flash column chromatography was performed with SiliCycle Silica-P Flash silica gel (60 Å pore size, 40–63 μm) and 50% ethyl acetate in hexanes as mobile phase, to furnish an off-white solid (58 mg, 87% yield). A portion was further purified by semi-preparative RP-HPLC (Waters Sunfire C18, 10 × 250 mm, 5 μm) using the following gradient elution (solvent A: water + 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), solvent B: acetonitrile + 0.1% TFA, flow rate 6.0 ml/min): 0–2 min 10% B; 2–20 min linear 10→45% B; 20–22 min linear 45–10% B; 22–25 min 10% B. Fractions were pooled, concentrated in vacuo, and the aqueous remainder was lyophilized to give a white powder (11.8 mg). RP-HPLC analysis indicated >99% purity at 210 and 254 nm, and no detectable 4HB (Waters Sunfire C18, 4.6 × 250 mm, 5 μM; solvents A/B as above, flow rate 1.00 ml/min) using the following gradient elution: 0–1 min 10% B; 1–20 min linear 10–100% B; 20–25 min 100% B; 25–27 min linear 100–10% B; 27–30 min 10% B.

NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Avance-500 spectrometer, calibrated to residual acetone-d6 as the internal reference (2.05 ppm for 1H NMR; 29.9 and 206.7 ppm for 13C NMR). 1H NMR spectral data are reported in terms of chemical shift (δ, parts per million), multiplicity, coupling constant (hertz), and integration. 13C NMR spectral data are reported in terms of chemical shift (δ, parts per million), multiplicity, and coupling constant (hertz). The following abbreviations indicate the multiplicities: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; m, multiplet; br, broad. 1H NMR (500 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 9.40 (br s, 1H), 7.70–7.65 (m, 1H), 7.63–7.57 (m, 1H), 7.39–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.05–7.02 (m, 1H), 6.71–6.69 (m, 1H), 6.32 (dd, J = 5.2, 16.1 Hz, 1H) (supplementary Fig. 1A); 13C NMR (125 MHz, acetone-d6) δ 159.5 (dt, J = 64.8, 8.6 Hz), 129.9 (tt, J = 58.8, 4.4 Hz), 125.9 (dt, J = 58.0, 9.2 Hz), 115.6 (dt, J = 64.6, 4.1 Hz) (supplementary Fig. 1B). GC-MS data were recorded using an Agilent 6890-5975 GC mass spectrometer equipped with an autosampler and an HP5 column; the sample was dissolved in ethanol. GC-MS (EI+) calculated for 13C612C3H8O3 M+, m/z 170.1, found 170.1.

E. coli growth and stable isotope labeling

E. coli strains are described in Table 1. The BW25113 ΔubiC::kan mutant strain was obtained from the Keio collection (27). Phage P1 was used to transduce the mutation into the MG1655 strain, yielding MG1655ubiC. The replacement of the chromosomal ubiC gene by the kan gene was checked by PCR amplification. Cells were inoculated in 100 ml of Luria broth (LB) for 16 h at 37°C. Cells (50 A600) from each sample were collected by centrifugation, and the collected pellets were resuspended in fresh LB medium in the presence of either 10 μg/ml of 13C6-4HB, 13C6-pABA, or 13C6-resveratrol, and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Incubations with vehicle control contained an equivalent volume of ethanol (in all conditions the final ethanol concentration was 0.2%). Cells were collected by centrifugation after 4 h and stored at −20°C for LC-MS/MS lipid analyses. For 13C6-coumarate labeling, HW272, HW25113, MG1655, and MG1655ubiC were inoculated in 5 ml of LB for 16 h at 37°C (MG1655ubiC was incubated in LB with 50 μg/ml kanamycin). Cells were diluted to 0.2 A600 in fresh media with 15 μg/ml of 13C6-coumarate and incubated for 24 h. Cells were pelleted for lipid extraction and LC-MS/MS analyses.

Animal cell culture and stable isotope labeling

U251 human glioma and 3T3 mouse fibroblast cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco). U87 human glioma cells were cultured in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Gibco). Human embryonic kidney 293T cells were cultured in DMEM with 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco). All cells were passaged in the stated media supplemented with 10% FBS (Omega Scientific) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (10,000 U/ml) (Life Technologies). Equal numbers of cells were plated approximately 12 h prior to treatment experiments. During treatment with stable isotope-labeled compounds, cells were cultured with 1% FBS, unless otherwise stated. Cells were cultured with the designated stable isotope-labeled compound for 24 h, then washed with PBS [137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM KH2PO4 (pH 7.4)], and released from the culture dish with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco). Aliquots of the released cells were stained with Trypan blue and the number of cells counted with the Cellometer Auto T4 (Nexcelom Bioscience); aliquots (5%) were also removed for determination of protein content (BCA assay; Thermo). The remaining cells in the suspension were collected by centrifugation. Cell pellets were stored at −20°C.

Lipid extraction

Cell pellets were thawed on ice and then suspended in 1.2 ml of methanol followed by 1.8 ml of petroleum ether. Q4 was added as an internal standard for the determination of Q6 content in yeast lipid extracts. Diethoxy-Q10 (28) was used as an internal standard for determination of Q9 and Q10 in mammalian cell lipid extracts and Q8 in E. coli cell lipid extracts. Samples were vortexed for 45 s, then the upper layer was removed to a new tube, and another 1.8 ml of petroleum ether was added to the lower phase and the sample was vortexed again for 45 s. The upper layer was again removed and combined with the previous organic phase. The combined organic phase was dried under a stream of nitrogen gas and resuspended in 200 μl of ethanol (USP; Aaper Alcohol and Chemical Co., Shelbyville, KY).

RP-HPLC-MS/MS

The RP-HPLC-MS/MS analyses were performed as previously described for determination of Q6 in yeast lipid extracts (11, 18) and determination of Q9 and Q10 in mammalian lipid extracts (28, 29). Briefly, a 4000 QTRAP linear MS/MS spectrometer from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA) was used. Applied Biosystem software, Analyst version 1.4.2, was used for data acquisition and processing. A binary HPLC solvent delivery system was used with either a Luna phenyl-hexyl column (particle size 5 μm, 100 × 4.60 mm; Phenomenex) for yeast cell lipid extracts or a Luna phenyl-hexyl column (particle size 3 μm, 50 × 2.00 mm; Phenomenex) for mammalian and bacteria cell lipid extracts. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (methanol:isopropanol, 95:5, with 2.5 mM ammonium formate) and solvent B (isopropanol, 2.5 mM ammonium formate). For separation of yeast quinones, the percentage of solvent B increased linearly from 0 to 5% over 6 min, and the flow rate increased from 600 to 800 μl/min. The flow rate and mobile phase were linearly changed back to initial condition by 7 min. For separation of bacteria and mammalian quinones, the percentage of solvent B for the first 1.5 min was 0%, and increased linearly to 10% by 2 min. The percentage of solvent B remained unchanged for the next min and decreased linearly back to 0% by 6 min. A constant flow rate of 800 μl/min was used. All samples were analyzed in multiple reaction monitoring mode; multiple reaction monitoring transitions were as follows: m/z 591/197.1 (Q6); m/z 610/197.1 (Q6H2 with ammonium adduct); m/z 597/203.1 (13C6-Q6); m/z 616/203.1 (13C6-Q6H2 with ammonium adduct); m/z 636/106 [2-octaprenyl-aniline (OA)]; m/z 637/107 [2-octaprenyl phenol (OP)]; m/z 642/112 (13C6-OA); m/z 643/113 (13C6-OP); m/z 652/122 [2-amino-3-octaprenylphenol (OAP)]; m/z 658/128 (13C6-OAP); m/z 682/150 (OAB); m/z 688/156 (13C6-OAB); m/z 727/197.1 (Q8); m/z 733/203.1 (13C6-Q8); m/z 746/197.1 (Q8H2 with ammonium adduct); m/z 750/203.1 (13C6-Q8H2 with ammonium adduct); m/z 880.7/197.0 (Q10 with ammonium adduct); m/z 882.7/197.0 (Q10H2 with ammonium adduct); m/z 886.7/203.0 (13C6-Q10 with ammonium adduct); m/z 888.7/203 (13C6-Q10H2 with ammonium adduct); m/z 812.6/197 (Q9 with ammonium adduct); m/z 455.6/197.1 (Q4); m/z 908.7/225.1 (diethoxy-Q10 with ammonium adduct); and m/z 910.7/225.1 (diethoxy-Q10H2 with ammonium adduct).

RESULTS

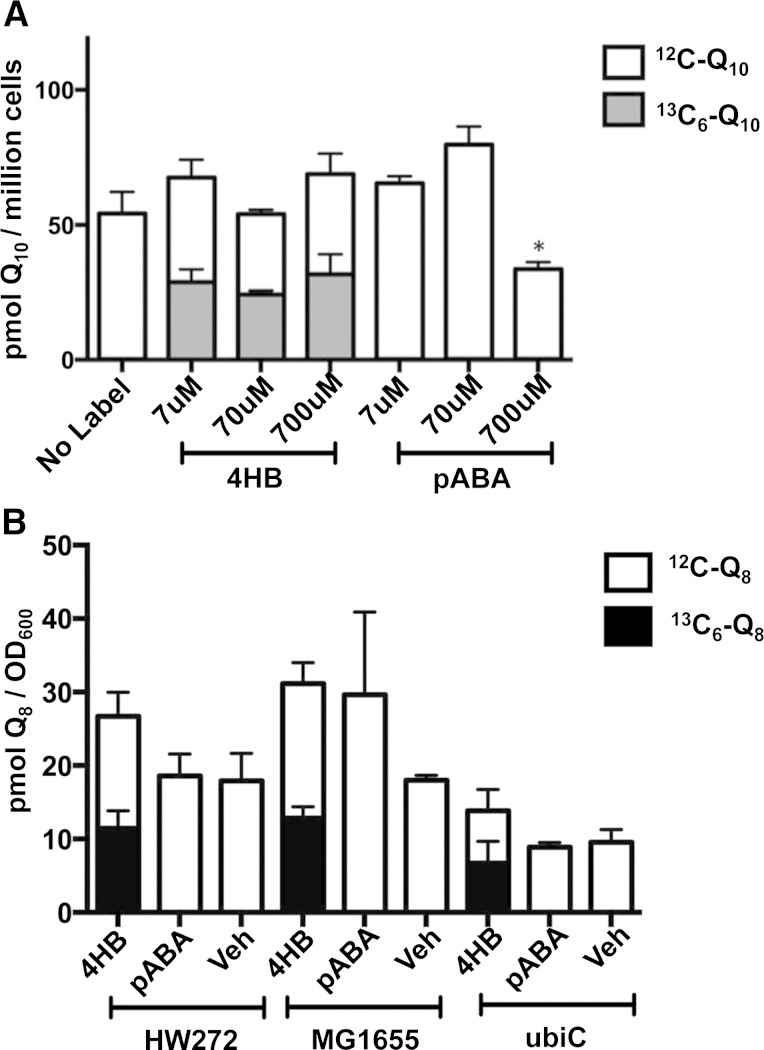

pABA is a demonstrated ring precursor of Q biosynthesis in the yeast S. cerevisiae (9, 18), but is not utilized as a ring precursor of Q biosynthesis in Arabidopsis (15). To investigate whether pABA may serve as a ring precursor of Q biosynthesis in mammalian cells, human U251 cells were cultured in the presence of 7, 70, or 700 μM of either 13C6-4HB or 13C6-pABA for 24 h prior to RP-HPLC-MS/MS analysis of Q content (Fig. 2A). U251 cells readily converted 13C6-4HB to 13C6-Q10, however, incubations with 13C6-pABA produced no detectable 13C6-Q10 (Fig. 2A, supplementary Fig. 2). Treatments of U251 cells with various 13C6-4HB concentrations did not alter the total Q10 content; however incubation with 700 μM 13C6-pABA resulted in significantly lower total Q10 content in mammalian cells (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

pABA is not utilized as an aromatic ring precursor to Q in mammalian or E. coli cells. A: Human glioblastoma (U251) cells were cultured and processed as described in the Materials and Methods. The plots show the total Q10 content detected by RP-HPLC-MS/MS under designated precursor conditions. The gray bar of each column represents 13C6-Q10, while the white bar represents 12C-Q10. Error bars represent standard deviation with n = 4. Cells were treated with the designated concentrations of either 13C6-4HB or 13C6-pABA. U251 cells incubated with 700 μM of 13C6-pABA had a significantly lower amount of total Q (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). B: HW272, MG1655, and MG1655ubiC E. coli cells were cultured and processed as described in the Materials and Methods section. The plots show total Q8 content detected by RP-HPLC-MS/MS under designated conditions. The black bar of each column represents 13C6-Q8, while the white bar represents 12C-Q8. Error bars represent SD with n = 4. Only E. coli cells treated with 13C6-4HB had detectable 13C6-Q8. Ethanol was used as vehicle control (Veh).

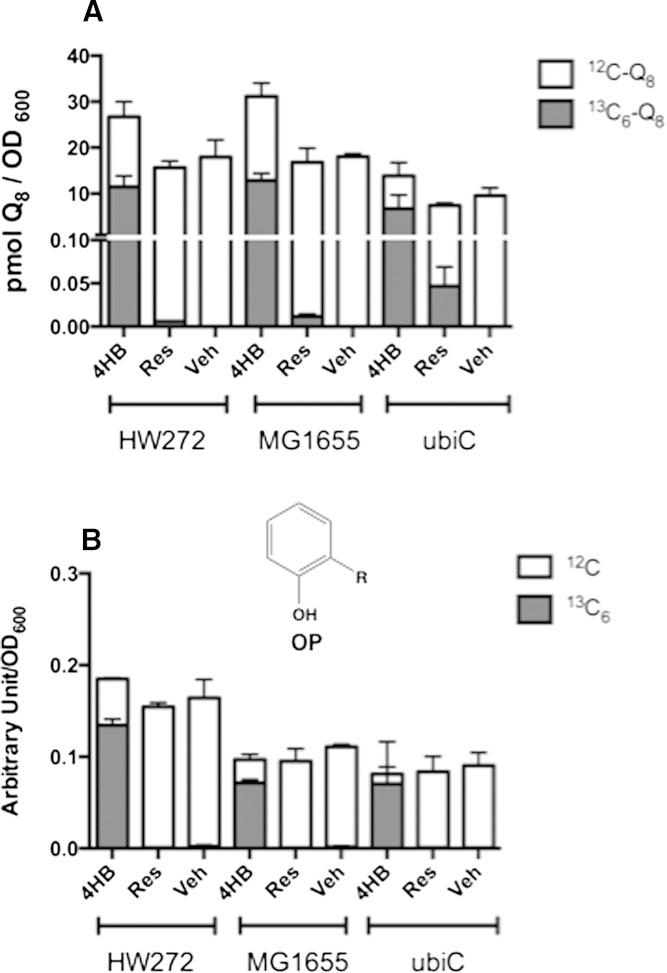

To examine whether pABA is utilized as a ring precursor in E. coli Q8 biosynthesis, 13C6-pABA or 13C6-4HB was added to cultures of the designated E. coli strains. HW272 and MG1655 are wild-type strains, while MG1655ubiC contains a deletion of the ubiC gene encoding chorismate pyruvate lyase (Table 1). Each E. coli strain was cultured in LB medium with aromatic ring precursors added to a final concentration of 10 μg/ml (Fig. 2B). Each of the E. coli strains incubated in the presence of 10 μg/ml 13C6-4HB accumulated significant amounts of 13C6-Q8. No incorporation of 13C6-pABA into 13C6-Q8 was detected with the wild-type strains. Interestingly, the E. coli ubiC mutant was also unable to use pABA to synthesize Q8. This result suggests that pABA is not utilized, even under conditions of impaired 4HB synthesis.

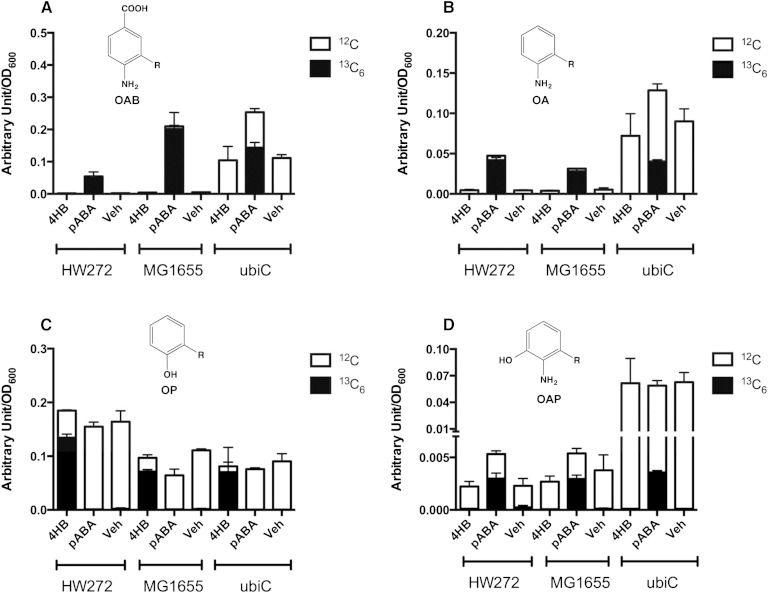

Detection of various polyprenylated derivatives of 13C6-pABA indicated that the E. coli strains tested were able to take up this ring. For example, 13C6-3-octaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid (OAB) indicated that 13C6-pABA-treated E. coli cells successfully absorbed 13C6-pABA from the medium and performed the ring prenyltransferase step catalyzed by UbiA (30) (Fig. 3A). 13C6-OA (Fig. 3B) was also readily detected in lipid extracts of the 13C6-pABA-treated E. coli cells. Notably, the ubiC mutant accumulated significantly more aniline-containing intermediates (Fig. 3A, B), even in the absence of pABA addition, presumably due to a deficiency in 4HB synthesis. The product 13C6-OAP (Fig. 3D) was also observed in 13C6-pABA-treated E. coli cells and is probably due to UbiI, which catalyzes the first hydroxylation step in Q8 biosynthesis (31). The ubiC mutant accumulated 10 times more 12C-OAP than HW272 or MG1655, a finding independent of the supplied 13C6-pABA, suggesting that OAP might be a “dead-end” product. 13C6-OAB, 13C6-OA, or 13C6-OAP were not detected in either the13C6-4HB-treated or control E. coli cells (Fig. 3A, B, D). 13C6-OP was detected only in 13C6-4HB-treated cells (Fig. 3C). These results suggest that although pABA is prenylated and can be further modified by UbiD, UbiX, and UbiI, E. coli may not be able to process the aniline-containing ring intermediates to later intermediates or to Q8.

Fig. 3.

E. coli cells produce 13C6-pABA-derived octaprenyl-products. HW272, MG1655, and MG1655ubiC cells were cultured and processed as described in the Materials and Methods. Bar plots show the total content of OAB (A), OA (B), OP (C), and OAP (D). Each bar represents mean ± SD. The black bar of each column represents the designated 13C6-labeled intermediate, while the white bar represents the 12C-intermediate. Each y axis represents the area under the peak of interest first normalized by the internal standard (diethoxy-Q10), and then by the value of OD600 of the extracted cell pellets.

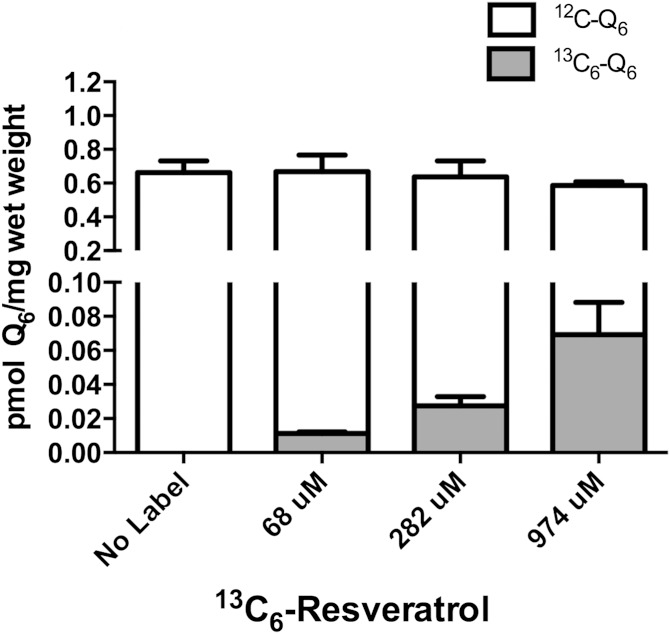

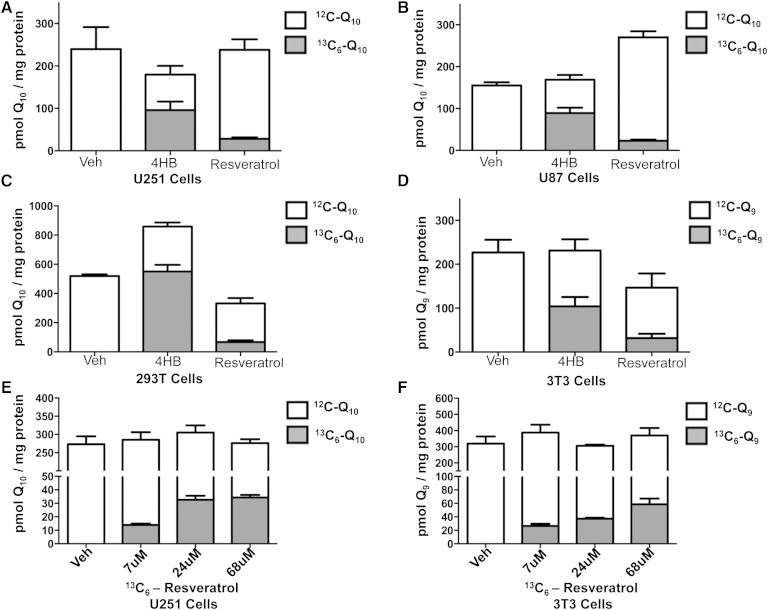

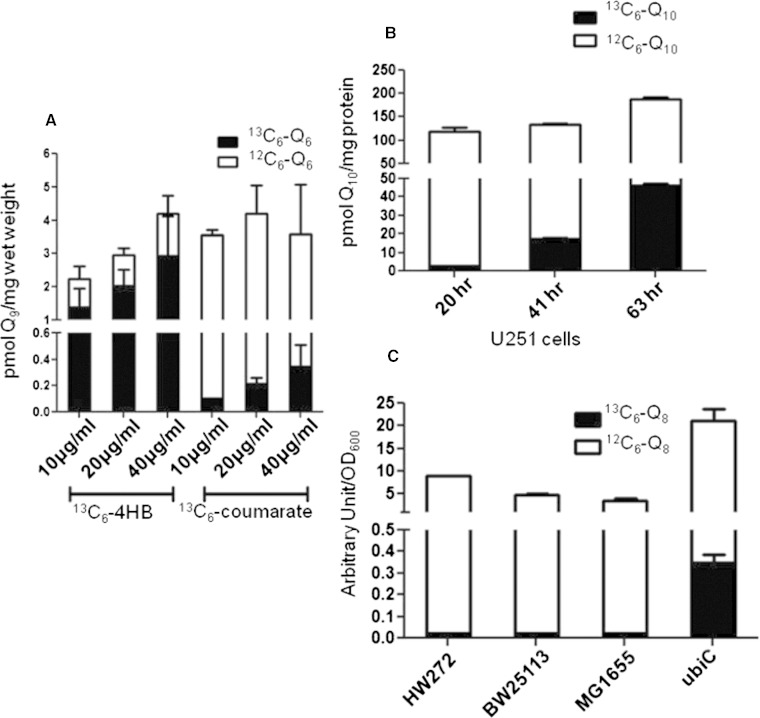

Given that S. cerevisiae can utilize either 4HB or pABA in Q6 biosynthesis, we investigated the use of other possible aromatic ring precursors. Surprisingly, wild-type yeast could use resveratrol as a ring precursor in the synthesis of Q6 (Fig. 4). W303 cells cultured in the presence of 68, 282, or 974 μM of 13C6-resveratrol showed increasing amounts of 13C6-Q6, while the ethanol control samples contained no detectable 13C6-Q6. Notably, the increased amount of resveratrol did not alter the total Q6 content. We next examined whether human or mouse cells could use resveratrol as a ring precursor to Q. The three human cell lines we examined were able to convert resveratrol to Q, as shown by the accumulation of 13C6-Q10 (Fig. 5A–C, supplementary Fig. 3A–C). 13C6-Q9 (Fig. 5D, supplementary Fig. 3D) also accumulated in mouse 3T3 fibroblasts, when cultured in the presence of 70 μM of 13C6-resveratrol. Although cells cultured with 13C6-4HB accumulated significantly more 13C6-Q10 than when cultured with 13C6-resveratrol, the incorporation of 13C6-resveratrol into 13C6-Q10 accounted for approximately 10% of the total Q10, a proportion that was much higher than that observed in wild-type yeast cells (the 13C6-Q6 was less than 1% of the total Q6). 13C6-Q10 content in U251 and 13C6-Q9 3T3 cells increased in response to the increasing concentrations of 13C6-resveratrol, while the total Q content again remained unaltered (Fig. 5E, F). Unfortunately, higher concentration (>70 μM) of resveratrol induced cell death, thus we were not able to examine the amount of 13C6-Q synthesized in the presence of higher 13C6-resveratrol concentrations.

Fig. 4.

13C6-resveratrol is a ring precursor to Q6 biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae. Yeast W3031B wild-type cells incubated with 0, 68, 282, or 974 μM of 13C6-resveratrol were cultured and analyzed as described in the Materials and Methods. The gray bar represents 13C6-Q6 and the white bar indicates 12C-Q6. Q4 was used as the internal standard.

Fig. 5.

Human and mouse cells utilize 13C6-resveratrol as a ring precursor in Q biosynthesis. U251 cells (A); U87 cells (B); 293T cells (C); and 3T3 cells (D) were cultured in medium with 1.0% FBS in the presence of either 13C6-4HB (278 μM), 13C6-resveratrol (70 μM), or ethanol as vehicle control for 24 h prior to collection. Increasing concentrations of resveratrol does not alter total Q levels in mammalian cells: U251 (E) and 3T3 (F) cells cultured in the presence of 0, 7, 24, or 68 μM 13C6-resveratrol were processed and analyzed. Collected cells were extracted and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS as described in the Materials and Methods. The gray bars represent 13C6-containing Q, and the white bars represent 12C-Q. Error bars represent SD (n = 4). Diethoxy Q10 was used as an internal standard.

E. coli also utilized resveratrol as an alternative ring precursor to Q, although to a lesser extent when compared with yeast, mouse, or human cells. HW272 and MG1655 cells cultured in LB medium in the presence of 10 μg/ml 13C6-resveratrol accumulated trace amounts of 13C6-Q8 (Fig. 6A, supplementary Fig. 4A). In comparison, 10 μg/ml of 13C6-4HB resulted in 13C6-labeling of more than two-thirds of the total Q content in the same cells. However, the E. coli ubiC mutant, with a defect in de novo synthesis of 4HB, produced significantly more 13C6-Q8 when treated with 13C6-resveratrol (Fig. 6A, supplementary Fig. 4B). 13C6-OP was detected only when E. coli strains were cultured in the presence of 13C6-4HB, and not with 13C6-resveratrol (Fig. 6B), suggesting that step(s) at which resveratrol is used as a ring precursor may not depend on its conversion to 4HB, or that the production of 4HB from resveratrol is slow compared with the step where OP is utilized.

Fig. 6.

E. coli ubiC mutant cells utilize resveratrol as a ring precursor to Q biosynthesis. Wild-type HW272, GM1655, and mutant MG1655ubiC cells were cultured in LB medium in the presence of 10 μg/ml of 13C6-4HB, 13C6-resveratrol, or ethanol as vehicle control (Veh). Collected cells were extracted and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS as described. Each bar represents mean ± SD (n = 4). The dark bar of each column represents 13C6-Q8 (A) or 13C6- OP (B), while the white bar of each column represents 12C-Q8 (A) or 12C-OP (B).

Given the structural similarity of resveratrol with p-coumarate, we tested the ability of yeast to utilize 13C6-coumarate as a ring precursor of 13C6-Q6. Yeast wild-type BY4741 cells were cultured in SD-complete medium with 7, 70, or 700 μM of either 13C6-4HB or 13C6-coumarate for 24 h (Fig. 7A). We found that while the total amount of Q6 did not change with different amounts of 13C6-coumarate, the amount of 13C6-Q6 increased with higher concentrations of 13C6-coumarate, although the incorporation was lower as compared with 13C6-4HB. U251 human cells were labeled with 7, 70, or 700 μM of either 13C6-4HB or 13C6-coumarate for 24 h (Fig. 7B). We found that more 13C6-Q10 accumulated when U251 cells were treated with increasing concentrations of 13C6-coumarate. Similar to yeast cells, U251 cells showed enhanced conversion of 13C6-4HB to Q as compared with 13C6-coumarate. Finally, we investigated the conversion of p-coumarate to Q8 in E. coli. The designated wild-type E. coli strains and the ubiC mutant were labeled with 15 μg/ml 13C6-coumarate for 24 h. 13C6-coumarate was converted to 13C6-Q8 much more efficiently in ubiC mutants than in the wild-type E. coli strains (Fig. 7C). The results show that p-coumarate is a ring precursor for Q biosynthesis in S. cerevisiae, E. coli, and human cells.

Fig. 7.

13C6-p-coumarate is a ring precursor of Q biosynthesis in yeast S. cerevisiae, human cells, and in the E. coli ubiC mutant. A: Yeast BY4741 wild-type cells were incubated in SD-complete medium with 7, 70, or 700 μM of either 13C6-4HB or 13C6-coumarate for 24 h. B: U251 cells were cultured in medium with 1% FBS in the presence of 7, 70, or 700 μM 13C6-coumarate for 24 h. C: Wild-type HW272, HW25113, GM1655, and mutant MG1655ubiC cells were cultured in LB medium in the presence of 15 μg/ml of 13C6-coumarate for 24 h. Collected cells were extracted and analyzed by RP-HPLC-MS/MS as described in the Materials and Methods. The dark bar of each column represents 13C6-Q and the white bar indicates 12C-Q. Each bar represents mean ± SD (n = 4).

DISCUSSION

Most schemes of Q biosynthesis continue to depict 4HB as the “sole” aromatic ring precursor. The finding that S. cerevisiae cells could utilize pABA as a ring precursor in Q biosynthesis was rather surprising because pABA is a crucial intermediate in folate biosynthesis (9, 18). The addition of pABA to either E. coli or human cells leads to a concentration-dependent inhibition of Q content (4, 32, 33). Another aromatic ring compound, 4-nitrobenzoic acid, inhibited Q biosynthesis in mammalian cells by competing with 4HB for Coq2 (34). While pABA does not function as a ring precursor of Q in Arabidopsis (15), it remained possible that pABA might still be utilized as a ring precursor in Q biosynthesis in human and E. coli cells. Therefore, we employed 13C6-pABA to investigate its fate in human and E. coli cells.

Treatment of cells with 13C6-pABA revealed that pABA was not an aromatic ring precursor to Q biosynthesis in either human or E. coli cells. In order to rule out the scenario that E. coli cells might utilize pABA as a ring precursor in Q biosynthesis only when the primary ring precursor 4HB is not available, we incubated ubiC mutants, which have defects in the de novo synthesis of 4HB in the presence of 13C6-pABA. However, even ubiC mutants were not able to utilize pABA for Q8 biosynthesis. Interestingly, we detected multiple nitrogen-containing intermediates that derived from 13C6-pABA. Detection of 13C6-OAB in all three strains (HW272, MG1655, and ubiC) confirmed 13C6-pABA uptake (Fig. 3A). Further modifications of the 13C6-OAB resulted in 13C6-OA and 13C6-OAP, indicating UbiA, UbiD/UbiX, and UbiI tolerated the amino ring substituent (Fig. 3B, D) (21). OAP accumulated in the ubiC mutant independent of 13C6-pABA addition, suggesting that OAP could be a dead-end product derived from endogenously produced unlabeled pABA. Neither HW272 nor MG1655 wild-type E. coli accumulated significant amounts of OAP, indicating that E. coli cells tend to process pABA through early steps in the Q biosynthetic pathway when 4HB content is low. These observations are consistent with studies that showed an E. coli mutant that lacked chorismate synthase converted pABA to OAB when cultured without addition of 4HB (33). We did not detect further downstream nitrogen-containing Q biosynthetic intermediates using targeted and limited-untargeted LC-MS/MS approaches. However, the presence of additional N-containing Q intermediates downstream of OAP cannot be ruled out.

It was shown that Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures are able to synthesize 4HB from p-coumarate (35) and A. thaliana uses p-coumarate to synthesize Q (15). Therefore, we investigated whether p-coumarate is a ring precursor for Q in different organisms. We found that yeast, E. coli, and human cells can derive Q from p-coumarate. This finding will help us understand how 4HB is generated in these organisms. In A. thaliana, p-coumarate is activated by CoA ligase and the aliphatic chain is shortened to 4HB in peroxisomes (15). Because yeast, human cell cultures, and E. coli can use p-coumarate to make Q, it is possible that these organisms derive 4HB from p-coumarate in a similar manner.

A wide spectrum of activities is attributed to stilbenoids produced by a variety of plants when under attack by pathogens (36). A stilbenoid of recent fame, resveratrol, acts as a chain-breaking antioxidant, modulates cellular antioxidant enzymes and apoptosis, and has beneficial effects on neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, eliciting metabolic responses similar to dietary restriction (37, 38). Although there is much controversy regarding the lifespan extension effects of resveratrol (39), its effects on age-associated diseases in animal models has generated considerable enthusiasm for research on its mechanism of action (40). Many questions remain regarding resveratrol biodistribution, its metabolism, and the biological effects of resveratrol metabolites (41). The beneficial health effects of resveratrol have led to vigorous research investigating its mechanisms of action.

Here we show that resveratrol serves as an aromatic ring precursor in Q biosynthesis in E. coli, yeast, and mammalian cells. Wild-type E. coli barely utilized resveratrol for Q biosynthesis; however, significant incorporation of the resveratrol ring into Q8 was observed in ubiC mutants. Preferential incorporation of alternate ring precursors in the E. coli ubiC mutant strain is presumably due to the defect in synthesis of 4HB. In contrast, approximately 10% of the total Q content in human and mouse cells harbored the ring derived from 13C6-resveratrol after 24 h of incubation. The maximum concentration of resveratrol tested was lower than either 4HB or pABA because resveratrol induced apoptotic cell death (42). Thus, we monitored cell viability in our experiments and limited the amount of resveratrol tested in order to avoid induction of cell death.

The metabolism of resveratrol responsible for its incorporation into Q has not been determined. Animals harbor two carotenoid cleaving enzymes, BCO1 and BCO2, and both are homologs of the carotenoid cleavage oxidase family (43). BCO1 is cytosolic and is responsible for cleaving β-carotene to form two molecules of retinal, while BCO2 is located in the inner mitochondrial membrane and acts on xanthophylls (44). It is tempting to speculate that BCO2, which has broader substrate specificity, might possibly cleave stilbenoids to produce two ring aldehyde products. Other family members of carotenoid cleavage enzyme in bacteria and fungi cleave resveratrol to produce 4-hydroxy-benzaldehyde and 3,5-dihydroxy-benzaldehyde (45, 46). Notably the 4′ hydroxyl group of resveratrol has been identified as crucial for antioxidant and neuroprotective effects of stilbenoids (47). It seems likely that other stilbenoids may serve as ring precursors of Q. For example, processing of piceatannol (trans-3,5,3′4′-tetrahydroxystilbene) by a fungal carotenoid cleavage oxidase family member (48), generates 3,4-dihydroxy-benzaldehyde, a ring precursor that could potentially bypass the Coq6 hydroxylase step of Q biosynthesis upon Coq2-prenylation (49).

Of the more than one hundred clinical trials testing the efficacy of resveratrol or other polyphenols (clinical trials.gov), few determine the metabolic fate of the administered supplement. When metabolism of resveratrol is studied, the focus is on aqueous soluble polar metabolites of resveratrol, including sulfated and glucuronidated conjugation products (50). The new finding that a metabolic conversion of resveratrol into Q occurs in eukaryotes shows that exogenous antioxidants may be utilized as precursors to synthesize a wholly different class of molecule. The effects of resveratrol in mimicking calorie restriction (37, 38) may be due in part to its conversion to Q, a lipid known to induce anti-inflammatory responses (51), an essential component of mitochondrial energy metabolism, and a potent lipid soluble antioxidant (4). Investigation of the pharmacological responses to diverse dietary polyphenols (e.g., curcumin) should be expanded to include this molecular fate. Further investigation on this subject will give us a better understanding on the origin of the benzenoid moiety of Q in different organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Laurent Loiseau, Frederic Barras, and Fabien Pierrel for the generous gift of the MG1655 and MG1655ubiC E. coli strains. They also thank F. Pierrel for important suggestions regarding the [13C6-pABA] labeling studies. They acknowledge the University of California at Los Angeles Molecular Instrumentation Core proteomics facility for the use of QTRAP 4000, National Institutes of Health S10RR024605 for support of mass spectrometry, and NSF CHE-1048804 for NMR measurements.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- [13C6]pABA

- p-amino[aromatic-13C6]benzoic acid

- DoD

- drop out dextrose

- 4HB

- 4-hydroxybenzoic acid

- LB

- Luria broth

- OA

- 2-octaprenyl-aniline

- OAB

- 3-octaprenyl-4-aminobenzoic acid

- OAP

- 2-amino-3-octaprenylphenol

- OP

- 2-octaprenyl phenol

- pABA

- para-aminobenzoic acid

- p-coumarate

- para-coumarate

- Q

- coenzyme Q or ubiquinone

- QH2

- coenzyme QH2 or ubiquinol

- Qn

- coenzyme Q with n number of isoprene units in the polyisoprenoid tail

- RP-HPLC-MS/MS

- reverse phase-HPLC-MS/MS

- TFA

- trifluoroacetic acid

This work was supported by NSF MCB-1330803 (C.F.C.), National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM071779 (O.K.), and the Sontag Foundation (S.J.B.). NIH S10RR024605 provided support for mass spectrometry, and NSF CHE-1048804 for NMR measurements.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains supplementary data in the form of four figures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bentinger M., Tekle M., Dallner G. 2010. Coenzyme Q–biosynthesis and functions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 396: 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowicka B., Kruk J. 2010. Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1797: 1587–1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentinger M., Brismar K., Dallner G. 2007. The antioxidant role of coenzyme Q. Mitochondrion. 7(Suppl): S41–S50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turunen M., Olsson J., Dallner G. 2004. Metabolism and function of coenzyme Q. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1660: 171–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsuo Y., Nishino K., Mizuno K., Akihiro T., Toda T., Matsuo Y., Kaino T., Kawamukai M. 2013. Polypeptone induces dramatic cell lysis in ura4 deletion mutants of fission yeast. PLoS ONE. 8: e59887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inaba K. 2009. Disulfide bond formation system in Escherichia coli. J. Biochem. 146: 591–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang M., Wakitani S., Hayashi K., Miki R., Kawamukai M. 2008. High production of sulfide in coenzyme Q deficient fission yeast. Biofactors. 32: 91–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson C. M., Kazantzis M., Wang J., Venkatraman S., Goncalves R. L., Quinlan C. L., Ng R., Jastroch M., Benjamin D. I., Nie B., et al. 2015. Dependence of brown adipose tissue function on CD36-mediated coenzyme Q uptake. Cell Reports. 10: 505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pierrel F., Hamelin O., Douki T., Kieffer-Jaquinod S., Muhlenhoff U., Ozeir M., Lill R., Fontecave M. 2010. Involvement of mitochondrial ferredoxin and para-aminobenzoic acid in yeast coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 17: 449–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y., Hekimi S. 2013. Mitochondrial respiration without ubiquinone biosynthesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22: 4768–4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie L. X., Ozeir M., Tang J. Y., Chen J. Y., Jaquinod S. K., Fontecave M., Clarke C. F., Pierrel F. 2012. Overexpression of the Coq8 kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae coq null mutants allows for accumulation of diagnostic intermediates of the coenzyme Q6 biosynthetic pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 287: 23571–23581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran U. C., Clarke C. F. 2007. Endogenous synthesis of coenzyme Q in eukaryotes. Mitochondrion. 7(Suppl): S62–S71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allan C. M., Hill S., Morvaridi S., Saiki R., Johnson J. S., Liau W. S., Hirano K., Kawashima T., Ji Z., Loo J. A., et al. 2013. A conserved START domain coenzyme Q-binding polypeptide is required for efficient Q biosynthesis, respiratory electron transport, and antioxidant function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1831: 776–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allan C. M., Awad A. M., Johnson J. S., Shirasaki D. I., Wang C., Blaby-Haas C. E., Merchant S. S., Loo J. A., Clarke C. F. 2015. Identification of Coq11, a new coenzyme Q biosynthetic protein in the CoQ-synthome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 290. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block A., Widhalm J. R., Fatihi A., Cahoon R. E., Wamboldt Y., Elowsky C., Mackenzie S. A., Cahoon E. B., Chapple C., Dudareva N., et al. 2014. The origin and biosynthesis of the benzenoid moiety of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 26: 1938–1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clarke C. F. 2000. New advances in coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Protoplasma. 213: 134–147. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olson R. E., Rudney H. 1983. Biosynthesis of ubiquinone. Vitam. Horm. 40: 1–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marbois B., Xie L. X., Choi S., Hirano K., Hyman K., Clarke C. F. 2010. para-Aminobenzoic acid is a precursor in coenzyme Q6 biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 27827–27838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He C. H., Xie L. X., Allan C. M., Tran U. C., Clarke C. F. 2014. Coenzyme Q supplementation or over-expression of the yeast Coq8 putative kinase stabilizes multi-subunit Coq polypeptide complexes in yeast coq null mutants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1841: 630–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui T. Z., Kaino T., Kawamukai M. 2010. A subunit of decaprenyl diphosphate synthase stabilizes octaprenyl diphosphate synthase in Escherichia coli by forming a high-molecular weight complex. FEBS Lett. 584: 652–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aussel L., Pierrel F., Loiseau L., Lombard M., Fontecave M., Barras F. 2014. Biosynthesis and physiology of coenzyme Q in bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1837: 1004–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nichols B. P., Green J. M. 1992. Cloning and sequencing of Escherichia coli ubiC and purification of chorismate lyase. J. Bacteriol. 174: 5309–5316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson R. E., Bentley R., Aiyar A. S., Dialameh G. H., Gold P. H., Ramsey V. G., Springer C. M. 1963. Benzoate Derivatives as Intermediates in the Biosynthesis of Coenzyme Q in the Rat. J. Biol. Chem. 238: 3146–3148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke D. J., Amberg D. C., Strathern J. N. 2005. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Course Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Plainview, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yaffe M. P., Schatz G. 1984. Two nuclear mutations that block mitochondrial protein import in yeast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 81: 4819–4823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robbins R. J., Schmidt W. F. 2004. Optimized synthesis of four isotopically labeled (13C-enriched) phenolic acids via a malonic acid condensation. J. Labelled Comp. Radiopharm. 47: 797–806. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baba T., Ara T., Hasegawa M., Takai Y., Okumura Y., Baba M., Datsenko K. A., Tomita M., Wanner B. L., Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2: 2006.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falk M. J., Polyak E., Zhang Z., Peng M., King R., Maltzman J. S., Okwuego E., Horyn O., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Ostrovsky J., et al. 2011. Probucol ameliorates renal and metabolic sequelae of primary CoQ deficiency in Pdss2 mutant mice. EMBO Mol. Med. 3: 410–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gasser D. L., Winkler C. A., Peng M., An P., McKenzie L. M., Kirk G. D., Shi Y., Xie L. X., Marbois B. N., Clarke C. F., et al. 2013. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis is associated with a PDSS2 haplotype and, independently, with a decreased content of coenzyme Q10. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 305: F1228–F1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gulmezian M., Hyman K. R., Marbois B. N., Clarke C. F., Javor G. T. 2007. The role of UbiX in Escherichia coli coenzyme Q biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 467: 144–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajj Chehade M., Loiseau L., Lombard M., Pecqueur L., Ismail A., Smadja M., Golinelli-Pimpaneau B., Mellot-Draznieks C., Hamelin O., Aussel L., et al. 2013. ubiI, a new gene in Escherichia coli coenzyme Q biosynthesis, is involved in aerobic C5-hydroxylation. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 20085–20092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alam S. S., Nambudiri A. M., Rudney H. 1975. 4-Hydroxybenzoate: polyprenyl transferase and the prenylation of 4-aminobenzoate in mammalian tissues. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 171: 183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton J. A., Cox G. B. 1971. Ubiquinone biosynthesis in Escherichia coli K-12. Accumulation of an octaprenol, farnesylfarnesylgeraniol, by a multiple aromatic auxotroph. Biochem. J. 123: 435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forsman U., Sjoberg M., Turunen M., Sindelar P. J. 2010. 4-Nitrobenzoate inhibits coenzyme Q biosynthesis in mammalian cell cultures. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6: 515–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loscher R., Heide L. 1994. Biosynthesis of p-Hydroxybenzoate from p-Coumarate and p-Coumaroyl-Coenzyme A in cell-free extracts of Lithospermum erythrorhizon cell cultures. Plant Physiol. 106: 271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Likhtenshtein G. 2010. Stilbenes: Applications in Chemistry, Life Sciences and Materials Science. 1st edition. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baur J. A., Sinclair D. A. 2006. Therapeutic potential of resveratrol: the in vivo evidence. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5: 493–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timmers S., Konings E., Bilet L., Houtkooper R. H., van de Weijer T., Goossens G. H., Hoeks J., van der Krieken S., Ryu D., Kersten S., et al. 2011. Calorie restriction-like effects of 30 days of resveratrol supplementation on energy metabolism and metabolic profile in obese humans. Cell Metab. 14: 612–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burnett C., Valentini S., Cabreiro F., Goss M., Somogyvari M., Piper M. D., Hoddinott M., Sutphin G. L., Leko V., McElwee J. J., et al. 2011. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature. 477: 482–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smoliga J. M., Vang O., Baur J. A. 2012. Challenges of translating basic research into therapeutics: resveratrol as an example. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 67: 158–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vang O., Ahmad N., Baile C. A., Baur J. A., Brown K., Csiszar A., Das D. K., Delmas D., Gottfried C., Lin H. Y., et al. 2011. What is new for an old molecule? Systematic review and recommendations on the use of resveratrol. PLoS ONE. 6: e19881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jiang H., Zhang L., Kuo J., Kuo K., Gautam S. C., Groc L., Rodriguez A. I., Koubi D., Hunter T. J., Corcoran G. B., et al. 2005. Resveratrol-induced apoptotic death in human U251 glioma cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 4: 554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lobo G. P., Amengual J., Palczewski G., Babino D., von Lintig J. 2012. Mammalian carotenoid-oxygenases: key players for carotenoid function and homeostasis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1821: 78–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palczewski G., Amengual J., Hoppel C. L., von Lintig J. 2014. Evidence for compartmentalization of mammalian carotenoid metabolism. FASEB J. 28: 4457–4469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marasco E. K., Schmidt-Dannert C. 2008. Identification of bacterial carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase homologues that cleave the interphenyl alpha,beta double bond of stilbene derivatives via a monooxygenase reaction. ChemBioChem. 9: 1450–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz-Sánchez V., Estrada A. F., Limon M. C., Al-Babili S., Avalos J. 2013. The oxygenase CAO-1 of Neurospora crassa is a resveratrol cleavage enzyme. Eukaryot. Cell. 12: 1305–1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Foti Cuzzola V., Ciurleo R., Giacoppo S., Marino S., Bramanti P. 2011. Role of resveratrol and its analogues in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: focus on recent discoveries. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 10: 849–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brefort T., Scherzinger D., Limon M. C., Estrada A. F., Trautmann D., Mengel C., Avalos J., Al-Babili S. 2011. Cleavage of resveratrol in fungi: characterization of the enzyme Rco1 from Ustilago maydis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 48: 132–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ozeir M., Muhlenhoff U., Webert H., Lill R., Fontecave M., Pierrel F. 2011. Coenzyme Q biosynthesis: Coq6 is required for the C5-hydroxylation reaction and substrate analogs rescue coq6 deficiency. Chem. Biol. 18: 1134–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walle T. 2011. Bioavailability of resveratrol. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1215: 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmelzer C., Kohl C., Rimbach G., Doring F. 2011. The reduced form of coenzyme Q10 decreases the expression of lipopolysaccharide-sensitive genes in human THP-1 cells. J. Med. Food. 14: 391–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu G., Williams H. D., Zamanian M., Gibson F., Poole R. K. 1992. Isolation and characterization of Escherichia coli mutants affected in aerobic respiration: the cloning and nucleotide sequence of ubiG. Identification of an S-adenosylmethionine-binding motif in protein, RNA, and small-molecule methyltransferases. J. Gen. Microbiol. 138: 2101–2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Blattner F. R., Plunkett G., 3rd, Bloch C. A., Perna N. T., Burland V., Riley M., Collado-Vides J., Glasner J. D., Rode C. K., Mayhew G. F., et al. 1997. The complete genome sequence of Escherichia coli K-12. Science. 277: 1453–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.