Abstract

Objective

To develop and validate a patient-reported outcome measure for women with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB)

Study Design

Prospective cohort and cross-sectional studies

Setting

Outpatient women’s health facility

Population or Sample

Women ages 18 and 55 years with and without self-reported HMB

Methods

Utilising data from patients and clinicians, we developed a patient-reported outcome measure for HMB; the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire (MBQ). Participants in the validation studies completed demographic and general health questionnaires and either (1) bleeding and quality of life data collected daily on handheld computers and the MBQ after one month or (2) the MBQ at enrollment only. A subset of women also completed the SF-36 generic quality of life questionnaire. We performed psychometric analyses of the MBQ to assess its internal consistency as well as its content and concurrent validity and ability to discriminate between women with and without HMB.

Main Outcome Measures

Psychometric properties of the questionnaire

Results

Overall, 182 women participated in the MBQ validation studies. We found that the MBQ domains were internally consistent (Cronbach’s alpha =0.87–0.94). There was excellent correlation between daily bleeding-related symptom data and the MBQ completed at one month (rho >0.7 for all domains). We found low to moderate correlation between the MBQ scores and SF-36 scores (rho= −0.15 to −0.45). The MBQ clearly discriminated between women with and without HMB (mean MBQ score=10.6 versus 30.8, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

The MBQ is a valid patient-reported outcome measure for HMB that has the potential to improve the evaluation of women with self-reported HMB in research and clinical practice.

Keywords: abnormal uterine bleeding, AUB, heavy menstrual bleeding, patient-reported outcome measures, quality of life, psychometric, validity

INTRODUCTION

Up to 30% of women suffer from heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) at some point in their lives.1–3 Women who report HMB suffer diminished quality of life secondary to their symptoms, scoring lower than their counterparts without heavy bleeding on validated health-related quality of life questionnaires. Although objectively measured menstrual blood loss has been used in many studies as the “gold standard” for evaluating women reporting HMB, measured blood loss does not provide a comprehensive picture of the patient experience with bleeding.2, 4, 5 Recent research in the area of HMB has recognized the importance of measuring “patient experience” as an outcome,6 and the National Institute of Clinical Excellence from the UK suggests that any intervention for HMB should aim to improve quality of life rather than focusing on menstrual blood loss.7 Similarly, a working group from National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) in the United States has suggested that studies on reproductive health measure patient-centered quality of life for all clinical trials.8, 9

Several studies have recommended using a menstrual bleeding-specific quality of life instrument, though no one instrument has been considered “standard” for use across all studies on treatment of HMB.6, 10, 11 To address this lack of one standard and widely accepted validated measure for bleeding-related quality of life, we aimed to independently develop and validate a patient-reported outcome instrument: for research and clinical care of women with HMB. The objectives of this study were to develop and validate a comprehensive patient-reported outcome (PRO) instrument for HMB, the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire (MBQ).

METHODS

Validation of the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire (MBQ) involved a pilot study and two other studies that involved prospective electronic daily diary data collection and cross-sectional data collection. These studies were approved by our institutional IRB.

Instrument Development

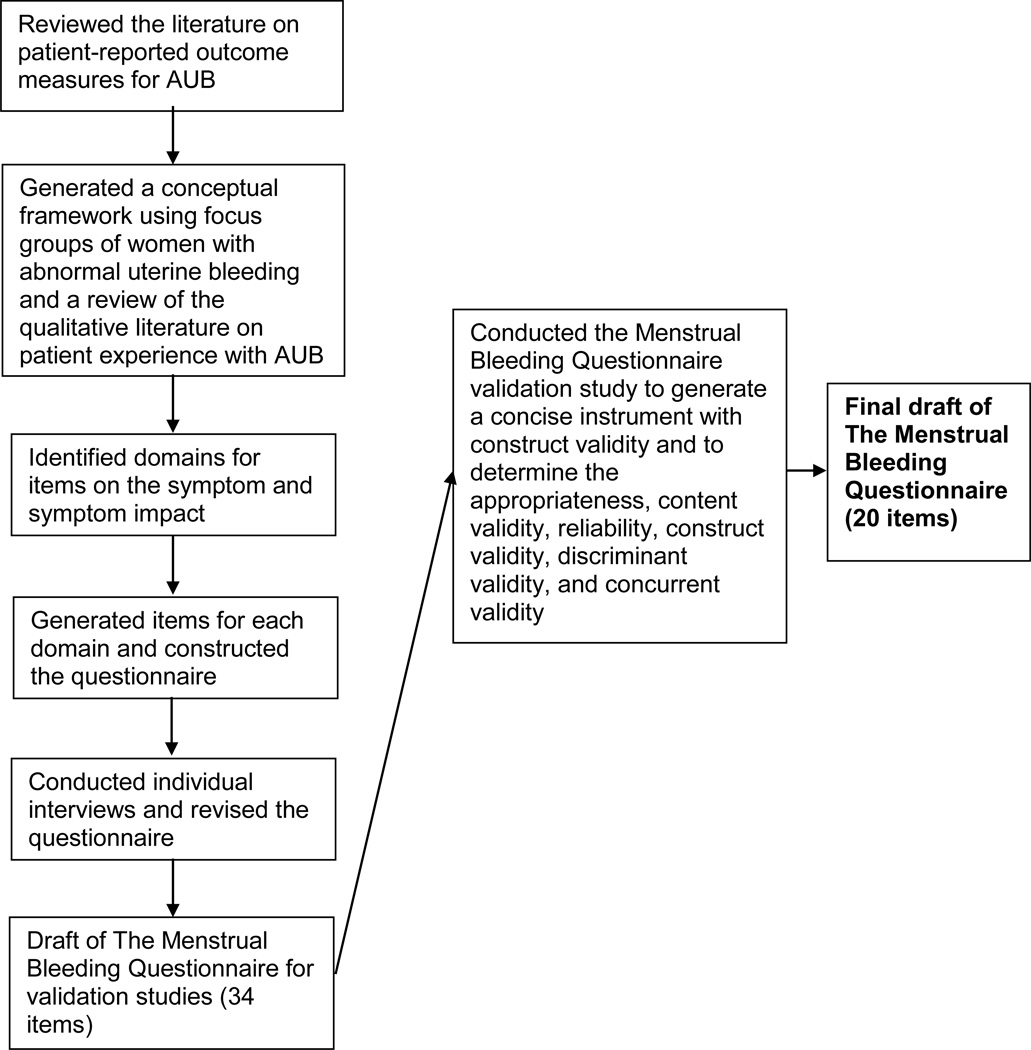

We developed the MBQ, which covered a recall period of one month, using information obtained from an extensive literature review,10 patient focus group sessions,12 a national survey of U.S. gynaecologists,13 and expert review (content and patient-reported outcomes).

In the focus group sessions, we found that inability to contain menstrual flow was a key issue influencing quality of life in women with HMB, which was associated with fear about bleeding through clothes when others may notice and avoidance behaviour surrounding menses such as changing plans and missing work.12 We generated a conceptual framework summarizing these themes, which was incorporated into the MBQ. The content of the questions and the response options were generated based on the discussions with women in our focus group work. The questions and corresponding numeric score assigned to each response is shown in Appendix S1 along with specific instructions for questionnaire scoring. The first version of the questionnaire contained 34 items and addressed whether or not the woman had any bleeding in the previous month (1 item), the amount of bleeding (11 items), bleeding regularity or predictability (5 items), pain (1 item), and bleeding-related quality of life (16 items). (Figure 2) Bleeding-related quality of life items incorporated how bleeding or anxiety related to bleeding affected work, social activities, or family activities. A range of three to six response options were available for each question and covered how often the respondent experienced different symptoms or events, such as bleeding through clothes in public or changing social plans because of concerns about bleeding. The number of questions in each domain reflected the level of importance assigned to these domains by women involved in the focus groups.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram for the development and validation of the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire

Validation study participants and methods

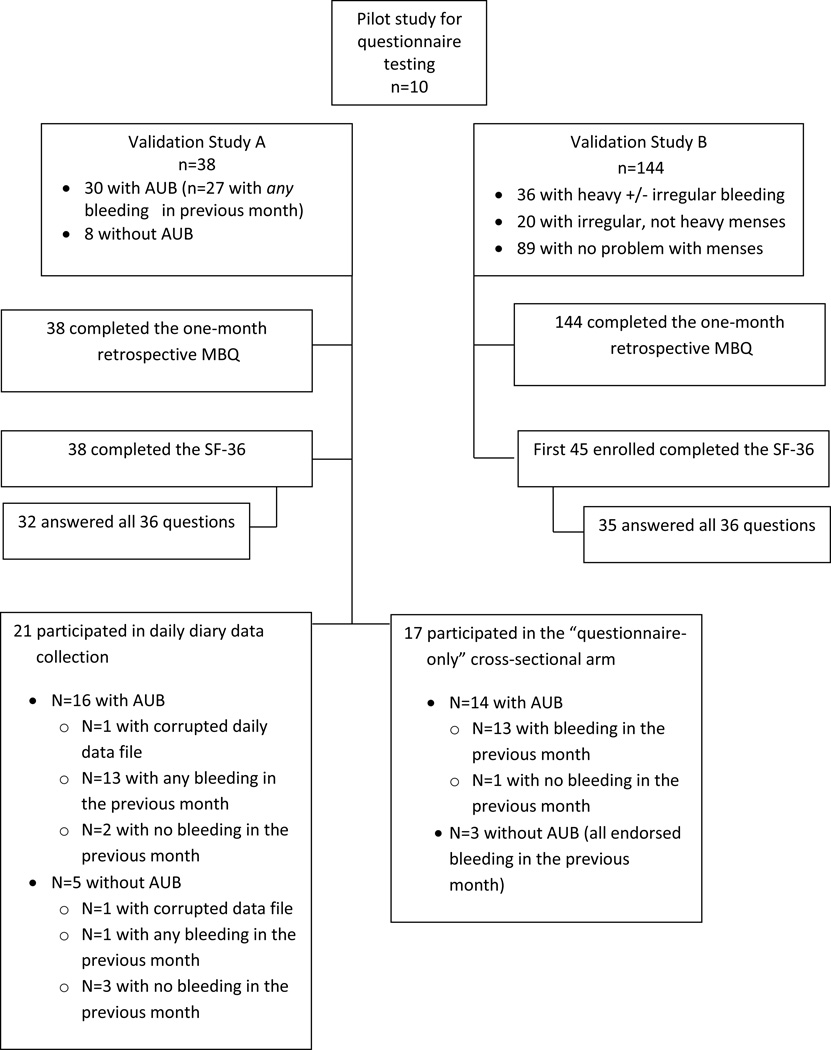

We validated the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire using three studies. Throughout the remainder of the manuscript, we refer to these studies as the pilot study, Validation Study A, and Validation Study B. We first performed a pilot study to evaluate the comprehension of questions and response options and the comprehensiveness of the questionnaire as a whole. Validation Study A included a prospective daily data collection arm and a cross-sectional questionnaire-only arm (for women who could not comply with daily data collection) to assess the validity of the questionnaire and whether or not the one-month retrospective MBQ reflected the day-to-day experiences of respondents. Validation Study B was a cross-sectional study to test whether or not the MBQ could discriminate between women with and without HMB. For all studies, non-pregnant women were included if they were between ages 18 and 55 years, and were able to read and write in English, and able to give informed consent.

In the pilot study, recruitment was restricted to women who reported abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) over the previous six months defined as experiencing prolonged (> 8 days), irregular, or heavy menses on average). For Validation Study A and Validation Study B, we recruited women with and without self-reported AUB. Women were recruited from an outpatient women’s health clinic. Women presenting for non-pregnancy related visits and between the ages of 18 and 55 years were approached by a research assistant and screened for participation in the study. Women in the pilot testing study and Validation Study A signed informed consent to participate in the study. Women in Validation Study B were informed about the study and instructed that their informed consent was implied by their completion and return of the questionnaire.

For the pilot testing, we recruited who then completed all questionnaires involved in the study. Following their completion of study instruments, we conducted individual interviews with participants to elicit opinions about, and comprehension of, the questions and the questionnaire as a whole. Specifically, we asked participants to address whether or not any questions were difficult to understand and what important questions may be missing and should be added. We made minor revisions to study instruments in response to comments received during these interviews.

For Validation Study A, participants were eligible for the prospective daily data collection arm of the study if they stated that they could participate in daily diary data collection for the next one month and did not plan to have a hysterectomy during that time period. For the purposes of assessing recall bias, we took a subset of MBQ questions and reframed them to be administered daily (25 items with a recall period of one day) and weekly (28 items with a recall period of one week). Eligible participants were consented and completed these electronic daily and weekly bleeding questionnaires on handheld computers for one month. Participants received detailed instructions on how to use the handheld computers, which captured the date and time the data were entered into the device. At one-month follow-up, all participants completed the one month recall MBQ and the SF-36. We used the daily diary data to evaluate the appropriateness and the content validity of the one-month recall questionnaire. Otherwise eligible participants who did not feel that they could participate in the daily data collection study were consented for a questionnaire-only arm of the study and completed the one-month recall MBQ and the SF-36 at the time of enrollment.14 The SF-36 is a 36 item survey that includes physical health and mental health component questions that are grouped into eight total domains. The SF-36 has been used as a general health related quality of life measure in several studies on HMB.10, 11

Validation Study B was a cross-sectional study where participants were required to complete a demographic and general health questionnaire and a one-month recall MBQ. Additionally, the first 45 participants enrolled were given the SF-36 to complete. Women with and without self-reported problems with HMB were included in this arm of the study. We used the data from this population to determine the construct validity and whether or not the one-month recall MBQ could discriminate between women with and without self-reported HMB.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses of demographic and general health data were performed by Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. All analyses were performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Scores were calculated for each domain and then summed to obtain the total score. Prior to scoring, we recoded responses such that a higher value for each item indicated worse symptoms/lower quality of life. Items were rescaled with zero as the lowest response value. Not applicable responses were omitted from score calculations. For respondents who were not currently employed, we imputed responses for work-related quality of life questions from similarly worded family-related quality of life questions. To accommodate missing responses, each domain-specific score was computed from the mean of non-missing responses multiplied by the total number of items in the domain.

We performed several different analyses of the data to determine the appropriateness, content validity, construct validity, concurrent validity and to assess floor and ceiling effects of the MBQ. In view of the variation in heaviness, regularity and impact on quality of life of monthly menstrual bleeding we did not assess test-retest reliability as a measure of instrument quality. For item reduction, we focused on item-domain relationships within the MBQ. We calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients to summarize each item-domain relationship and standardized Cronbach’s alpha as a measure of internal consistency among all items in a domain. Our goal was to retain the questions that correlated most highly with domain-specific (heaviness, pain, quality of life) and total score. Once we completed the item reduction process, we re-assessed the internal consistency among the items in the domains of the revised questionnaire.

To determine whether or not one-month recall of menstrual symptoms and quality of life as captured by the MBQ accurately captured daily and weekly experiences with symptoms and quality of life (appropriateness, content validity), we used data collected in the prospective electronic daily data collection arm of Validation Study A. For the evaluation of correlations between daily score and monthly score and weekly score and monthly score, we first summated the scores on all daily questionnaires and all weekly questionnaires completed by the participant. We then generated an average daily score and an average weekly score for the participant and calculated the correlation between these average scores and the one-month MBQ score. We did this to determine if the one-month retrospective questionnaire accurately summarized the experiences participants prospectively catalogued over the month. We calculated Spearman rank correlations for domain and total scores between (1) daily data and the monthly MBQ and (2) weekly data and the monthly MBQ. To evaluate the concurrent validity of the MBQ, we used data from both the participants who were given the SF-36 and completed all 36 items (32 of 38 participants in Validation Study A and 35 of 45 participants in Validation Study B) We used the SF-36 as the “gold standard” because it has been used previously and validated for studies on HMB. We tested for concurrent validity (a measure of how well a particular test correlates with a previously validated measure) rather than convergent validity because the MBQ measures condition-specific constructs that we think are different from the constructs in the SF-36.15 We compared the domain and total scores obtained with the MBQ to SF-36 norms-based domain and component scores.

Heavy menstrual bleeding is a subjective complaint and incorporates a spectrum of symptoms such that a similar amount of bleeding may be a problem for one woman but not another. Therefore, we assessed the ability of the MBQ to distinguish between women with and without a reported problem with HMB, using data from Validation Study B. We hypothesized that if designed properly, the MBQ would be scored higher among women who identify HMB as a problem than women who also have the symptom (menstrual bleeding) but do not identify their bleeding as a problem. Based on their responses to the demographic and general health questionnaire, women were classified as having no problem with their menstrual bleeding, menstrual bleeding that was irregular only, or menstrual bleeding that was heavy (+/− irregular). We compared these three groups of women in terms of total scores and domain scores from the MBQ to determine if the questionnaire could discriminate between women with and without reported problems with their uterine bleeding.

To inform our sample size calculations for correlation testing, we set α=0.05 and β=0.20. In order to detect a strong correlation (r=0.7) between item and domain scores and between MBQ and SF-36 scores, we needed a total of 25 participants to complete the MBQ and the SF-36. To determine whether or not the MBQ could discriminate between women with and without heavy bleeding, we needed a total of 126 participants to provide complete data on the MBQ in order to detect a 0.5 standard deviation difference in overall MBQ scores..

RESULTS

Overall, 192 women participated in the MBQ validation studies; 10 were involved with the pilot study, 38 were enrolled in Validation Study A, and 144 were enrolled in Validation Study B. (Figure 1). Of the women in Validation Study A and Validation Study B, the mean age of study participants was 32 years (18–53 years), and 35.8% were white non-Hispanic (n=63), 13.1% were white Hispanic (n= 23), 18.2% were black non-Hispanic (n=32), and 3.4% were black Hispanic (n= 6). (Table 1) The majority of participants had at least a 12th grade education (82.2%). Overall, 60.3% (n=70) of participants reported experiencing irregular menstrual bleeding and 53% (n=62) reported experiencing HMB.

Figure 1.

Participants in the MBQ validation Studies

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the validation study population (n=182)

| N* (column %) | |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean (Range) | 32.0 (18.0 – 53.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White, non-Hispanic | 63 (35.8) |

| White, Hispanic | 23 (13.1) |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 32 (18.2) |

| Black, Hispanic | 6 (3.4) |

| Other | 59 (33.5) |

| First language spoken | |

| English | 131 (72.4) |

| Spanish | 54 (29.8) |

| Other | 18 (9.9) |

| Education | |

| Less than HS | 32 (17.8) |

| 12th grade/GED | 50 (27.8) |

| Some college | 62 (34.4) |

| Completed 4 year degree | 36 (20.0) |

| Irregular periods now | |

| No | 46 (39.7) |

| Yes | 70 (60.3) |

| Duration of irregular periods | |

| Never | 58 (32.4) |

| <1 year | 38 (21.2) |

| 1–2 years | 17 (9.5) |

| >2 years | 66 (36.9) |

| Heavy periods now | |

| No | 55 (47.0) |

| Yes | 62 (53.0) |

| Duration of heavy periods | |

| Never | 45 (25.3) |

| <1 year | 50 (28.1) |

| 1–2 years | 16 (9.0) |

| >2 years | 67 (37.6) |

N may total to less than 182 secondary to missing data on the item

Item reduction

For item reduction, we analyzed data from the 27 participants in Validation Study A who reported AUB and reported having any bleeding during the month of data collection. Items were removed (1) if they duplicated another item in the questionnaire; or (2) if the item-domain Spearman rank correlation was <0.4 and the standardized Cronbach alpha after deleting the item was either the same or increased. Based on these rules, we removed three questions from the heaviness domain, two questions from the irregularity domain, and eight questions from the quality of life domain. (Figure 2) Table 2 includes the number of items remaining in each domain after item reduction, the total possible score, the internal consistency of the domain and the range of item to domain correlations. After the item reduction, each domain had good to excellent internal consistency (0.87–0.94) and good to excellent item-domain correlation (0.53–0.92).

Table 2.

Summary of the domain scores, internal consistency of the domains, and ranges of item-domain correlations within each questionnaire domain after item-reduction

| Domain | Number of items |

Total possible score |

Internal Consistency |

Range of item- domain correlation |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom | Heaviness | 8 | 29 | 0.87 | 0.53–0.92 |

| Pain | 1 | 3 | ---- | ---- | |

| Symptom Impact | Quality of Life | 8 | 37 | 0.94 | 0.69–0.82 |

Content validity

To assess whether or not the one-month retrospective MBQ accurately captured the woman’s daily and weekly experience with menstrual bleeding over the previous month, we analysed data from the 13 participants in Validation Study A who participated in the prospective daily data collection arm and reported AUB and reported any menstrual bleeding in the previous month. These women recorded data on a mean of 29 days (range 17–41 days) and the proportion of days with a survey completed was 86.2% (SD 12.3%). For bleeding heaviness, there was excellent correlation between the daily score and the one month score (rho=0.83, 95% CI 0.52–0.95) and the weekly score and one month score (rho 0.80, 95% CI 0.39–0.95). The pain domain scores correlated well for the daily and monthly (rho=0.7, 95%CI 0.25–0.9) and weekly and monthly (rho=0.92, 95% CI 0.72–0.98) scores. For the quality of life domain, there was excellent correlation between daily and monthly (rho=0.82, 95% CI 0.49–0.95) and weekly and monthly (rho=0.88, 95% CI: 0.64–0.96) scores. Finally, for the irregularity questions, we found excellent correlation between the weekly and the monthly scores (rho 0.89, 95% CI 0.67–0.97). An assessment of the symptom irregularity could not be assessed on a daily interval.

Concurrent Validity

We used concurrent validity to assess how the MBQ scores correlated with a commonly used validated quality of life measure, the SF-36. To evaluate the concurrent validity of the MBQ, we used data from the 67 participants enrolled Validation Study A or Validation Study B who were assigned to complete both the MBQ and the SF-36 and completed all the SF-36 items. (Table 3) The MBQ had a moderate correlation with the SF-36 bodily pain subscale (rho = −0.45, p=0.0001) and small correlation with the SF-36 Physical Component Score (PCS) (rho = −0.27, p=0.03), the SF-36 Energy subscale (rho = −0.15, p=0.2), and the SF-36 Mental Component Score (MCS) (rho −0.27, p=0.03).

Table 3.

Correlation of the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire Score and the SF-36 Score (n=67)

| Total MBQ score (20 items) | ||

|---|---|---|

| SF-36 Domains | Spearman correlation coefficient |

p-value |

| Physical health summary score (PCS) | −0.27 | 0.03 |

| Mental health summary score (MCS) | −0.27 | 0.03 |

| Overall health | −0.22 | 0.07 |

| Physical health limits physical activity | −0.21 | 0.08 |

| Physical health limits work activity | −0.25 | 0.04 |

| Bodily pain | −0.45 | 0.0001 |

| Energy | −0.15 | 0.2 |

| Physical/emotional health limits social activity | −0.38 | 0.001 |

| Emotional problems | −0.23 | 0.06 |

| Personal/emotional problems limit daily activity | −0.33 | 0.006 |

The analysis was limited to participants who completed all SF-36 questions.

Higher SF-36 summary and domain scores indicate better physical and mental health, while higher MBQ scores indicate worse symptoms and a negative impact on quality of life.

Ability of the instrument to distinguish between women with and without a problem with heavy menstrual bleeding

We analysed the data obtained from 144 women in Validation Study B and compared scores between women who reported no problems with their menstrual period (n=88), women with problems with irregular bleeding only (n=20), and women with heavy menses that were either regular or irregular (n=36). (Table 4) For the full questionnaire, we found significant differences between the mean scores of women with no problem with their menstrual period and women with heavy menstrual periods (mean 10.6 versus 30.8 respectively, p<0.0001). Comparing women with no problem with their menstrual period to women with menses that were irregular but not heavy we found no differences in scores (mean 10.6 versus 12.7 respectively, p=0.4).

TABLE 4.

Discriminant validity of the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire

| Reported problem with uterine bleeding | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (n=88) |

Irregular only (n=20) |

Heavy +/− Irregular (n=36) |

None vs. Irregular |

None vs. Heavy |

|

| Total MBQ 20 items | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.6 (8.6) | 12.7 (9.5) | 30.8 (14.0) | 0.4 | <0.0001 |

| IQR | 4.0 – 15.5 | 4.0 – 19.5 | 23.0 – 37.5 | ||

| Bleeding heaviness 8 items | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 5.6 (4.4) | 6.2 (4.1) | 13.1 (5.7) | 0.7 | <0.0001 |

| IQR | 2.0 – 7.5 | 2.5 – 9.5 | 10.0 – 15.0 | ||

| Bleeding irregularity 3 items | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.3 (1.8) | 3.9 (1.8) | 4.4 (1.4) | 0.2 | 0.002 |

| IQR | 2.0 – 5.0 | 2.0 – 6.0 | 3.5 – 6.0 | ||

| Pain 1 items | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.8 (1.0) | 2.1 (0.8) | 0.4 | 0.004 |

| IQR | 1.0 – 2.0 | 1.0 – 2.5 | 2.0 – 3.0 | ||

| Quality of life 8 items | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (4.6) | 4.2 (5.0) | 13.3 (7.6) | 0.5 | <0.0001 |

| IQR | 0 – 6.0 | 0 – 9.0 | 7.5 – 20.0 | ||

Floor and Ceiling Effects Assessment

The final version of the MBQ had 20 items with a possible score of 0 to 75. We looked at floor and ceiling effects separately for Validation Study A and Validation Study B. In Validation Study A, no participants had either the highest or the lowest score. In Validation Study B, scores ranged from zero to 70, with only 2.8% (4/144) scoring zero on the MBQ.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) recommends that for a patient-reported outcome measure to be utilised in clinical research, it first must be validated.16 We developed and validated a patient-reported outcome measure for abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB), the Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire (MBQ), for use across studies of women experiencing AUB. We systematically validated the MBQ to ensure that it had content validity, construct validity, concurrent validity, and was able to distinguish between women with and without a problem with HMB. We determined that the MBQ was internally consistent with good item-domain correlations, reliable, and able to clearly discriminate between women with self-reported heavy menses and women with no reported problems with their menstrual periods.

Strengths and Limitations

One specific concern for patient-reported outcomes of chronic, intermittent problems such as HMB is that the “summary experience” obtained on a retrospective questionnaire may be subject to recall bias and the patient’s experience at the time she is completing the instrument. With our assessment of daily, weekly, and one-month questionnaire data we showed that recall bias was not a problem in the MBQ. Although daily data collection can be challenging due to “hoarding”, or, filling out the diaries retrospectively17, 18, we used a novel approach of having participants collect daily data on handheld computers that recorded the time of data entry. Using this method, we had excellent compliance with daily data collection and found that the MBQ responses accurately reflected daily and weekly experiences with menstrual bleeding. Additional strengths of our approach include the systematic process we used to develop the questionnaire using real input from women who have experienced HMB and validation of the questionnaire across a range of patient experiences.

Study limitations include the generalisability of our findings because the work was conducted at a single site and restricted to the English language. Additional work will be necessary to ensure that the MBQ is relevant to other languages and cultures. The questionnaire was conducted on paper rather than electronically. Further studies to evaluate electronic means of administering the MBQ and to assess the responsiveness of this instrument to change in clinical status are currently underway.

Interpretation

Development of patient-reported outcome measures for HMB is an active area of interest and investigation. Although questionnaires have been developed and used, they haven’t been used consistently across studies or become the “standard” by which menstrual bleeding-related quality of life is measured.19–22 The theoretical model we used as the foundation for our questionnaire was based on patient input and incorporates social embarrassment, fear of social embarrassment, and behavior changes to avoid embarrassment. This sets the MBQ apart from other quality of life questionnaires in terms of relevance to patients. In our focus group sessions, women expressed that social embarrassment and alteration of activities to avoid social embarrassment were dramatically affected by HMB and typical questions from available questionnaires covered these aspects in a manner that was too superficial to be meaningful.12

There is overlap between the MBQ and other available questionnaires but there are additional advantages of the MBQ compared with other bleeding specific quality of life instruments. These include the fact that the MBQ has been shown to accurately summarise the experiences participants prospectively catalogued over one month. The MBQ covers a range of symptoms, amount and regularity of bleeding as well as associated pain, and also the impact of symptoms on women’s lives and specifically on embarrassment and fear of social embarrassment based on focus group studies.

Although generic quality of life instruments, such as the Short-form-36 (SF-36) have been validated for use in studies on HMB, prior studies have suggested that completing these instruments is difficult for patients because of the intermittent nature of the symptom and the fact that the symptoms are typically not life-threatening.15, 23, 24 Not surprisingly, we found low to moderate correlation between the MBQ and the SF-36. Other studies assessing the validity of a condition-specific questionnaire, such as the Uterine Fibroids Symptoms-Quality of Life (UFS-QOL) questionnaire, against a broad health-related quality of life questionnaire such as the SF-36 generated similar findings.25 Our findings suggest that the MBQ, a condition specific patient reported outcome measure, evaluates different concepts than the SF-36. The MBQ includes questions about experiences that are relevant for generally healthy women and specific to the problem of HMB. This isn’t to suggest that validated general health questionnaires should be abandoned as an outcome measure for studies on AUB, rather that they should be used in combination with a condition-specific patient-reported outcome measure such as the MBQ.6

Conclusion

Patient reported outcomes in clinical trials provide important information for evaluating treatment effectiveness, especially for symptoms like AUB that are evaluated almost entirely by patient report. AUB has many treatment options that differ widely in terms of invasiveness and effectiveness, which is why the use of a single patient-reported outcome measure across studies could facilitate the interpretation of data on treatment effectiveness, facilitate comparison and summation of results across studies.11, 26 The development and validation of the MBQ appears to encourage its use as a patient reported outcome in future AUB research. External validation studies should be conducted to further support its use.

Acknowledgements

None

Funding

Dr. Matteson and this project were supported by a Career Development Award (K23HD057957) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Study conducted in Providence, RI

Disclosure of interests

None of the authors on this study have any relevant conflicts of interest (financial, personal, political, intellectual, or religious) to disclose.

Contribution to authorship

KAM and MAC contributed to the conception and design of the project, facilitated study conduct, planning and review of the data analyses, and drafting and revision of the submitted article. DMS contributed to the planning of the project, facilitated study conduct, and drafting and revision of the submitted article. CAR contributed to the conception and design of the project, performing the data analyses, and drafting and revision of the submitted article.

Details of ethics approval

The Menstrual Bleeding Questionnaire validation studies were approved by the Women and Infants Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB), Providence, RI, USA (IRB# 10-0073 approved August 2010 and IRB#11-0080 approved September 2011)

REFERENCES

- 1.Nielsen/NetRatings - A global leader in Internet media and market research. http://www.nielsen-netratings.com. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallberg L, Hogdahl AM, Nilsson L, Rybo G. Menstrual blood loss--a population study. Variation at different ages and attempts to define normality. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1966;45(3):320–351. doi: 10.3109/00016346609158455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu Z, Doan QV, Blumenthal P, Dubois RW. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding. Value in Health, Published on behalf of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2007;10(3):173–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Flynn N, Britten N. Menorrhagia in general practice--disease or illness. Social science & medicine (1982) 2000 Mar;50(5):651–661. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warner PE, Critchley HO, Lumsden MA, Campbell-Brown M, Douglas A, Murray GD. Menorrhagia II: is the 80-mL blood loss criterion useful in management of complaint of menorrhagia? American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2004;190(5):1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark TJ, Khan KS, Foon R, Pattison H, Bryan S, Gupta JK. Quality of life instruments in studies of menorrhagia: a systematic review. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, & Reproductive Biology. 2002;104(2):96–104. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clinical Guidelines on Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. National Institute of Clinical Excellence. National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidice LC, Sitruk-Ware R, Bremmer WJ, Hillard P. In: The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Scientific Vision Workshop on Reproduction. NICHD, editor. Bethesda, Md: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Acquadro C, Berzon R, Dubois D, Leidy NK, Marquis P, Revicki D, et al. Incorporating the patient's perspective into drug development and communication: an ad hoc task force report of the Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Harmonization Group meeting at the Food and Drug Administration, February 16, 2001. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2003 Sep-Oct;6(5):522–531. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2003.65309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matteson KA, Boardman LA, Munro MG, Clark MA. Abnormal uterine bleeding: a review of patient-based outcome measures. Fertility and sterility. 2008 Jul 15; doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahn DD, Abed H, Sung VW, Matteson KA, Rogers RG, Morrill MY, et al. Systematic review highlights difficulty interpreting diverse clinical outcomes in abnormal uterine bleeding trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Mar;64(3):293–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matteson KA, Clark MA. Questioning our questions: do frequently asked questions adequately cover the aspects of women's lives most affected by abnormal uterine bleeding? Opinions of women with abnormal uterine bleeding participating in focus group discussions. Women & health. 2010 Mar;50(2):195–211. doi: 10.1080/03630241003705037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matteson KA, Anderson BL, Pinto SB, Lopes V, Schulkin J, Clark MA. Practice patterns and attitudes about treating abnormal uterine bleeding: a national survey of obstetricians and gynecologists. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2011 Oct;205(4):321, e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical care. 1992 Jun;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkinson C, Peto V, Coulter A. Making sense of ambiguity: evaluation in internal reliability and face validity of the SF 36 questionnaire in women presenting with menorrhagia. Quality in Health Care. 1996;5(1):9–12. doi: 10.1136/qshc.5.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothman M, Burke L, Erickson P, Leidy NK, Patrick DL, Petrie CD. Use of existing patient-reported outcome (PRO) instruments and their modification: the ISPOR Good Research Practices for Evaluating and Documenting Content Validity for the Use of Existing Instruments and Their Modification PRO Task Force Report. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2009 Nov-Dec;12(8):1075–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lauritsen K, Degl' Innocenti A, Hendel L, Praest J, Lytje MF, Clemmensen-Rotne K, Wiklund I. Symptom recording in a randomised clinical trial: paper diaries vs. electronic or telephone data capture. Control Clin Trials. 2004;26(6):585–597. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaertner J, Elsner F, Pollmann-Dahmen K, Radbruch L, Sabatowski R. Electronic pain diary: a randomized crossover study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28(3):259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bushnell DM, Martin ML, Moore KA, Richter HE, Rubin A, Patrick DL. Menorrhagia Impact Questionnaire: assessing the influence of heavy menstrual bleeding on quality of life. Current medical research and opinion. 2010 Dec;26(12):2745–2755. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.532200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Chadha YC, Flett GM, Hall MH, Russell IT. Assessment of patients with menorrhagia: how valid is a structured clinical history as a measure of health status? Quality of Life Research. 1995;4(1):33–40. doi: 10.1007/BF00434381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lamping DL, Rowe P, Clarke A, Black N, Lessof L. Development and validation of the Menorrhagia Outcomes Questionnaire. British Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 1998;105(7):766–779. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaw RW, Brickley MR, Evans L, Edwards MJ. Perceptions of women on the impact of menorrhagia on their health using multi-attribute utility assessment. BJOG. 1998;105:1155–1159. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb09968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garratt AM, Ruta DA, Abdalla MI, Russell IT. SF 36 health survey questionnaire: II. Responsiveness to changes in health status in four common clinical conditions. Quality in Health Care. 1994;3(4):186–192. doi: 10.1136/qshc.3.4.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruta DA, Garratt AM, Russell IT. Patient centred assessment of quality of life for patients with four common conditions. Quality in Health Care. 1999;8(1):22–29. doi: 10.1136/qshc.8.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spies JB, Coyne K, Guaou Guaou N, Boyle D, Skyrnarz-Murphy K, Gonzalves SM. The UFS-QOL, a new disease-specific symptom and health-related quality of life questionnaire for leiomyomata. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2002 Feb;99(2):290–300. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matteson KA, Rahn DD, Wheeler TL, 2nd, Casiano E, Siddiqui NY, Harvie HS, et al. Nonsurgical management of heavy menstrual bleeding: a systematic review. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Mar;121(3):632–643. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182839e0e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]