Abstract

Limited research has explored the influence of perceived injunctive norms for distal (e.g., typical student) and proximal (e.g., close friend and parents) referents on hooking up. The current study examined the longitudinal relationships among perceived injunctive norms, personal approval and hooking up behavior, and the moderating effects of gender in a sample of heavy drinking college students. At Time 1, participants completed web-based assessments of personal approval of hooking up and perceptions of close friend, parent, and typical student approval. Three months later, participants reported on whether they had hooked up. The results of a path analysis indicated that greater perceived friend and parent approval predicted greater personal approval. Further, greater perceived approval by close friends and parents indirectly contributed to hooking up behavior as mediated by participants’ own approval. Multigroup analyses indicated that close friend injunctive norms were a stronger predictor of student approval for males, as compared to females. While previous research has often failed to find an association between perceived injunctive norms and hooking up, the current findings suggest that this may reflect the use of distal referents. The findings underscore that perceptions of close friend and family approval may be useful predictors of hooking up behavior.

Keywords: hooking up, injunctive norms, college students, longitudinal

Hooking up encompasses a range of intimate sexual behaviors (e.g., kissing, oral sex, vaginal intercourse) between non-dating partners for whom no obligation or commitment exists (Bogle, 2008; Garcia & Reiber, 2008; Owen, Rhoades, Stanley, & Fincham, 2010; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Between 56% and 84% of U.S. college students report ever hooking up (England, Shafer, & Fogarty, 2008; Gute & Eshbaugh, 2008; Paul & Hayes, 2002; Paul, McManus, & Hayes, 2000), and approximately half of students report past year hooking up (LaBrie, Hummer, Ghaidarov, Lac, & Kenney, 2014; Owen, Fincham, & Moore, 2011; Owen et al., 2010). During this developmental period, hooking up may play an important role in facilitating sexual exploration and development of sexual identity (e.g., Stinson, 2010) and students often report positive reactions to hooking up experiences (Lewis, Granato, Blayney, Lostutter, & Kilmer, 2012; Owen et al., 2011). Nonetheless, hooking up is also associated with a range of negative outcomes, including feelings of regret and shame (Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Grello, Welsh, & Harper, 2006; Paul & Hayes, 2002), as well as unwanted sex, sexually transmitted infections, and unplanned pregnancies (Fielder, Walsh, Carey, & Carey, 2014; Kahn et al., 2000, August; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Gaining a better understanding of college students’ hookup-related perceptions and behaviors may inform psychoeducational interventions aimed at raising awareness and reducing potential harms.

Hooking up is associated with a number of personality, psychological, and contextual factors (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Fielder & Carey, 2010b; Fielder, Walsh, Carey, & Carey, 2013; LaBrie et al., 2014; Paul & Hayes, 2002). One area that has received little attention is the influence of social norms on hooking up (Fielder et al., 2013). According to the social norms approach (Berkowitz, 2004; Perkins, 2002), people’s behavior is influenced by perceptions of what other people do (i.e., descriptive norms) and think (i.e., injunctive norms). In the case of injunctive norms, perceptions of others’ approval of a behavior often shape an individual’s own attitudes, which in turn influence their own behaviors (Perkins, 1997). Therefore, perceived injunctive norms have the potential to indirectly influence people’s behavior through personal attitudes. Research suggests that people are often inaccurate in their perceptions of others and tend to overestimate how permissive their peers are toward a range of problem behaviors (Borsari & Carey, 2003; LaBrie, Hummer, Lac, & Lee, 2010; Neighbors et al., 2007). Consistent with the social norms model, college students are found to overestimate how often other students hook up and how approving their peers are toward hooking up (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Holman & Sillars, 2012; Lambert, Kahn, & Apple, 2003; Reiber & Garcia, 2010).

Misperceived injunctive norms may have important implications for hooking up behaviors. Perceiving peers to be more comfortable than they actually are with hooking up may lead students to feel that they are expected to engage in sexual behaviors or even pressure others to do so (Lambert et al., 2003). Few studies have focused on the influence of injunctive norms on hooking up behavior. Using cross-sectional data, Barriger and Velez-Blasini (2013) found that typical student injunctive norms were positively associated with personal approval of hooking up, but not students’ actual hooking up behavior. Further, after controlling for personal approval and perceptions of how frequently other students hook up, injunctive norms were only weakly negatively associated with some forms of hooking up behaviors (e.g., performing oral sex, intercourse). Similarly, a longitudinal study examining predictors of hooking up behavior found that perceptions of how approving students’ acquaintances were toward hooking up did not predict whether students hooked up, nor did it predict the frequency of hookups that involved performing oral sex, receiving oral sex, or vaginal sex (Fielder et al., 2013).

Barriger and colleagues noted that the limited effects of injunctive norms on hooking up behaviors observed in past research may reflect the use of distal social referents (e.g., “typical student”) rather than proximal referents (e.g., close friends or parents). Based on Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954) and Social Impact Theory (Latane, 1981), proximal referents may be more relevant, salient, and important to a student’s sense of identity (Lewis & Neighbors, 2006) and therefore have a greater impact on students’ behavior. Indeed, research examining alcohol risk suggests that perceived norms for close friends (Cox & Bates, 2011; Korcuska & Thombs, 2003; LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2010) and parents (Neighbors et al., 2008) are more strongly associated with behaviors than perceived norms for the more distal typical student referent. Consistent with this research, Holman and Sillars (2012) found that a combined measure of perceived descriptive and injunctive norms for close friends predicted students’ own approval of and participation in hookups. Assessing multiple types of norms as one variable, however, limits inferences about the importance of proximal injunctive norms for hooking up behavior. Further, the influence of perceived descriptive norms may be less sensitive to the use of proximal referents than injunctive norms (Neighbors et al., 2008). Additional research is needed to determine the comparative effects of distal and proximal injunctive norms on students’ hooking up approval and behaviors, including the influence of perceived approval of both close friends and parents.

Current research examining the relationship between perceived norms and hooking up behaviors (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Fielder et al., 2013) have yet to explore the potential moderating effect of participant sex. Research has suggested that females are generally less approving of hooking up and feel less comfortable engaging in a range of hooking up behaviors compared to males (Allison & Risman, 2013; Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Lambert et al., 2003). This may in part reflect the continuing, although diminishing, sexual double standards whereby females are more likely to be negatively judged for hooking up, while males may be praised or socially rewarded (Allison & Risman, 2013; Bradshaw, Kahn, & Saville, 2010). Indeed, females are more likely to feel less satisfied and experience more negative emotions after a hookup (Grello et al., 2006; Owen et al., 2010; Paul & Hayes, 2002; Shukusky & Wade, 2012), while males may experience more benefits (Bradshaw et al., 2010).

While positive attitudes towards hooking up predict greater hooking up behavior for both males and females (Owen et al., 2010), it is not clear whether sex moderates the influence of injunctive norms on hooking up attitudes and behaviors. Research examining perceived alcohol norms indicates that, compared to females, males are more influenced by the perceived approval of peers than parents (Cail & LaBrie, 2010) and are less dependent on parents for approval and support (Lapsley, Rice, & Shadid, 1989). Therefore, we might expect perceived injunctive norms for parents to be more influential for females than males.

In the current study, we aimed to extend previous research by using longitudinal data to explore the relationships among perceived injunctive norms for distal and proximal referents and students’ hooking up attitudes and behaviors, as well as the possible moderating effect of sex. Although experimental designs are necessary to establish causality, in comparison to cross-sectional data, a longitudinal design provides a useful approach for making inferences about the direction of influence of perceived norms and approval on hooking up behavior. We hypothesized that proximal (e.g., close friend and parent) rather than the more general “typical student” injunctive norms would be stronger predictors of students’ hooking up attitudes and behaviors. Further, based on alcohol norm research, we expected perceived parental approval to be a stronger predictor of student attitudes and behaviors for female as compared to male students. Finally, based on the social norms model (Perkins, 2002), we predicted that the influence of injunctive norms on hooking up behavior would be mediated by students’ personal attitudes toward hooking up.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate students from three US universities taking part in a larger alcohol intervention study during the 2012–2013 academic year. The sites were a large public university in the Northwest enrolling 30,000 students, a private West Coast university with an enrollment of approximately 6,000 students, and a large public university in the South with nearly 40,000 students. The design and protocol were approved by the institutional review board of each participating university, and the registrar’s office on each campus provided a random list of enrolled students (N = 9,524). These students were sent an email invitation to participate in the study and a link to an online informed consent statement. Participants who provided informed consent were immediately directed to an online survey. A total of 2,123 (22.3%) students completed measures assessing their attitudes toward hooking up and normative beliefs (T1). Of these participants, 606 (28.5%) met the larger alcohol study criteria (i.e., males who reported consuming 5 or more drinks on one occasion in the past three months, and females who reported consuming 4 or more drinks per drinking occasion) and were eligible to receive an additional survey three months after T1 data collection (T2). Participants received $25 for completing each survey, with the exception of one site that increased the baseline incentive to $50 based on prior recruitment rates and incentives used in previous trials. Participants who were ineligible to take part in the longitudinal study were less likely to report hooking up at T1 (χ2 (1, N = 2,156) = 238.83, p < .001), had less approving attitudes toward hooking up (M = 3.06, t(2,121) = 5.13, p < .001), and perceived their close friends to be less approving of hooking up (M = 3.74, t(2,123) = 17.38, p < .001) in comparison to heavy drinkers who were eligible to participate.

The final sample consisted of 525 heavy drinking students (54.5% female) who completed both T1 and T2 hooking up measures. Participants were 18 to 26 years old (M = 20.6 years, SD = 1.69). Overall, 38.0% of the students identified as college seniors, 28.4% as college juniors, 20.2% as sophomores, and 13.4% as college freshman. The majority of the sample identified as White (61.3%), followed by 15.8% Asian, 7.8% Multi-ethnic, 4.8% Black / African American, 1% Native American / Alaskan Native, 1% Native Hawaiian / Pacific Islander, and 8.3% identified as other. In terms of ethnic composition, 20.9% identified as Hispanic / Latino. Overall, at T1 45.9% of participants reported having hooked up within the past three months.

Measures

Hooking up injunctive norms and approval

Prior to answering questions related to hooking up, the following definition was provided: “‘Hooking up’ is defined as engaging in physically intimate behaviors ranging from kissing to sexual intercourse with someone with whom you do not have a committed relationship. ‘Hooking up’ is defined as something both people agree to (consensual), including how far they go.”

At T1, participants were asked, “How much do you think the following people approve of hooking up?” and were provided with a list of the following referent groups: your parents (parent injunctive norms), your closest friends (close friend injunctive norms), typical male / female [same-university] college student (typical student injunctive norms), and yourself (own approval). Responses were measured on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly Disapprove) to 7 (Strongly Approve). Items were adapted from a measure of alcohol-related injunctive norms and approval (Baer, 1994).

Hooking up Behavior

At both T1 and T2, participants completed an item assessing the last time they had hooked up (0 = Never to 5 = Past week). The measure was dichotomized in order to assess whether the participant had hooked up in the past three months (0 = did not hookup in the past three months, 1 = did hookup in the past three months). The three month time period reflected the gap between the T1 and T2 data collection.

Results

Analysis Plan

Prior to analyses, variables’ distributional properties were examined. Skewness and kurtosis values did not exceed an absolute value of 0.87 for any of the measures. Path analysis using the MPLUS 6.12 statistical package (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011) was undertaken to examine the associations among injunctive norms, personal approval, and hooking up behavior. As the T2 hooking up behavior variable was dichotomous (0 = not hooked up, 1 = had hooked up), a robust weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011) was employed. Injunctive norms were allowed to correlate and were specified to predict students’ hooking up approval. Hooking up approval was permitted to predict hooking behavior at follow-up. Time 1 hooking up (0 = not hooked up, 1 = had hooked up), age, and race (0 = non-white, 1 = white), were included as covariates that predicted endogenous variables (i.e., T1 student approval and T2 hooking up behavior dependent variables). The adequacy of the proposed model was evaluated with several fit indices (i.e., model Χ2 test, Comparative Fit Index [CFI], and Root Mean-Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA]).

To assess the possible moderating effect of sex, multigroup analyses were performed using MPLUS. This involved comparing a configural model, in which parameters are freely estimated, to a model in which the structural regression paths were constrained to be equal for males and females (Byrne, 2012). As WLSMV estimation was employed, Χ2 testing to compare the nested models was performed using the DIFFTEST function (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2011). Wald Χ2 tests were used to test for sex differences in regression paths and indirect effects.

Perceived and Personal Hooking Up Approval

Participants’ perceptions of typical student hooking up approval (M = 5.39, SD = 1.26) and close friend approval (M = 5.14, SD = 1.62) were significantly higher than students’ own approval (M = 4.66, SD = 1.87), t(524) = −8.84, p < .001, d = .39 and t(524) = −8.53, p < .001, d = .37, respectively. In contrast, students perceived their parents to be significantly less approving than themselves (M = 2.36, SD = 1.51), t(524) = 30.11 p < .001, d = 1.31.

Path Analysis

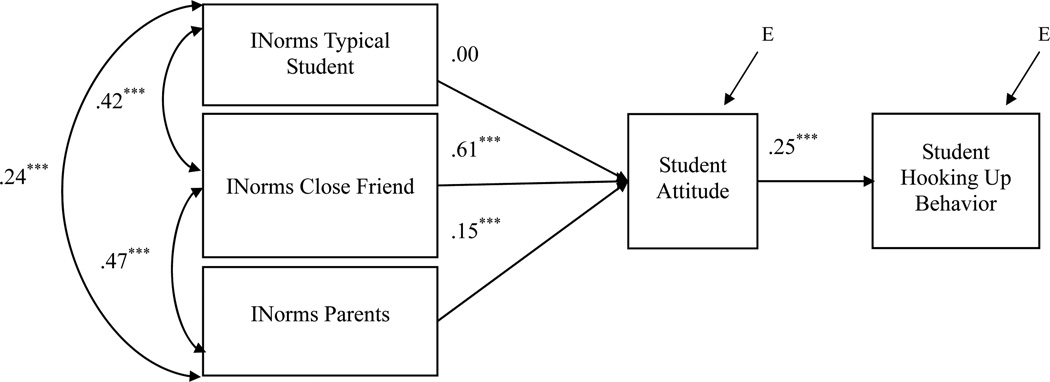

The model appeared to be a good fit to the data, Χ2 (3, N = 525) = 5.73, p = .13, CFI = .99, RMSEA = .04 (90% CI: .00, .09). The lagrange multiplier test (Chou & Bentler, 1990) indicated that the model could not be improved by incorporating any additional paths, including direct paths from injunctive norms to T2 behavior. The overall model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Path model. Standardized coefficients are presented. All paths have statistically controlled for time 1 hooking up, age and race on the endogenous variables. INorms = injunctive norms. E = predictive error. ***p < .001.

Direct Effects

Greater personal approval of hooking up was significantly predicted by greater perceived close friend and parent approval of hooking up (Figure 1). After statistically controlling for past hooking behavior, demographics and parent and close friend norms, perceptions of typical student approval did not significantly predict students’ own approval. Hooking up behavior at T2 was predicted by higher levels of T1 personal approval.

Indirect Effects

Tests of indirect effects were employed to examine whether there were significant indirect effects of T1 perceived norms on T2 hooking up behavior, mediated through student’s own approval. Greater perceived approval of hooking up by close friends (β = .15, SE = .03, p < .001) and parents (β = .04, SE = .01, p = .001) indirectly contributed to T2 hooking up behavior as significantly mediated by participants’ own approval of hooking up.

Gender Differences

T-tests were used to examine whether males and females differed in their approval of hooking up behavior and perceived injunctive norms (Table 1). Males reported greater personal approval of hooking up compared to females. In addition, males perceived their close friends, parents, and the typical student to be more approving of hooking up than female students. There was no significant difference in the proportion of females and males who reported hooking up at T2 (males = 45.2% females = 42.7%, Χ2 (1, N = 525) = 0.34, p = .56).

Table 1.

Gender Differences in Hooking Up Approval and Injunctive Norms

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t(523) | Cohen’s d |

| Perceived typical student approval | 5.82 | 1.05 | 5.03 | 1.31 | 7.55*** | 0.67 |

| Perceived close friend approval | 5.50 | 1.49 | 4.83 | 1.66 | 4.86*** | 0.42 |

| Perceived parent approval | 2.79 | 1.65 | 2.01 | 1.27 | 6.05*** | 0.53 |

| Student attitude toward hooking up | 5.10 | 1.78 | 4.34 | 1.89 | 4.38*** | 0.41 |

Note.

p < .001

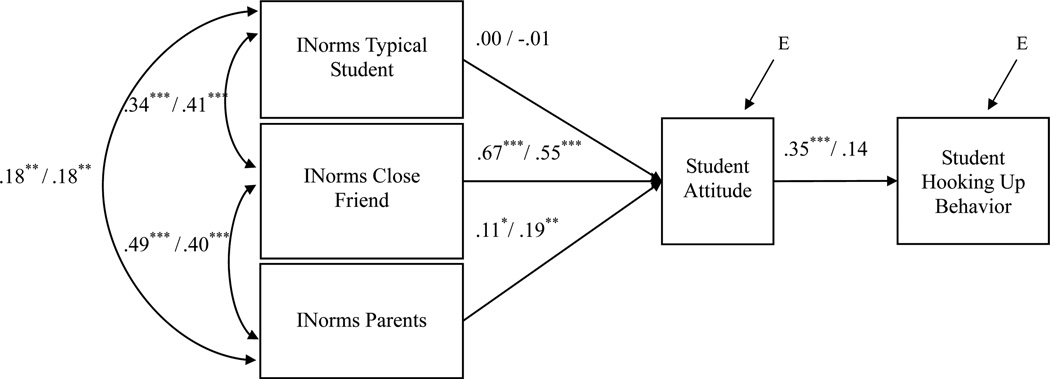

Multigroup analyses were used to examine whether sex moderated the relationship between injunctive norms and hooking up approval and behavior (Figure 2). The configural model, in which parameters were freely estimated for both sexes, provided evidence of good model fit for both males (Χ2 (3, N = 239) = 2.23) and females (Χ2 (3, N = 286) = 3.18). The chi-square difference test between the configural model and a constrained model was marginally significant (Χ2 = 17.22, p = .069), indicating that sex weakly moderated the relationship between injunctive norms and students’ attitudes and behavior. The Wald test of parameter constraints revealed significant sex differences for the associations between close friend injunctive norms and student approval, and student approval and T2 hooking up behavior. Close friend injunctive norms were a stronger predictor of student attitudes for male, as compared to female students (Wald (1) = 4.02, p = .045). Furthermore, personal approval was a stronger predictor of T2 behavior for males as compared to females (Wald (1) = 3.87, p = .049). There was also a significant sex difference in the indirect effect of T1 close friend injunctive norms on T2 hooking up behavior as mediated through student’s own approval (Wald (1) = 3.87, p = .049). Personal approval mediated the relationship between friend injunctive norms and T2 behavior for male, but not female students. No other direct or indirect paths significantly differed between males and females.

Figure 2.

Path model for males and females separately. Standardized coefficients are presented. Estimates before the slash apply to males; estimates after the slash apply to females. All paths have statistically controlled for time 1 hooking up, age and race on the endogenous variables. INorms = injunctive norms. E = predictive error. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to explore the relative influence of perceived injunctive norms on students’ hooking up behavior and attitudes as a function of reference groups, and to examine the moderating effect of gender on these relationships. Consistent with the broader injunctive norms literature (LaBrie, Hummer, Lac, et al., 2010; Neighbors et al., 2007; Neighbors et al., 2008), the findings indicate that more proximal referent groups (e.g., close friends and parents) are better predictors of student attitudes and behaviors than typical student referents. In support of the social norms model (Perkins, 2002), the influence of injunctive norms on behavior was found to be mediated by students’ own approval of hooking up. While the influence of parent norms was similar for males and females, close friend injunctive norms appeared to be a stronger predictor of students’ own attitudes for male students. These findings suggest that the lack of association between injunctive norms and hooking up outcomes observed in prior studies (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013; Fielder et al., 2013) may in part reflect the use of distal referents.

Students in the current study tended to be less approving of hookups than they perceived their peers and friends to be. This overestimation of others’ approval may influence students to become more approving themselves and increase the likelihood of students engaging in hookups. While hooking up is seen as a normative behavior that occurs during emerging adulthood (Bogle, 2008; Holman & Sillars, 2012) and is viewed as a positive experience by most students who engage in hooking up (Lewis et al., 2012; Owen et al., 2011), it is nonetheless associated with a number of negative consequences (e.g., sexual vicitimization, STIs, regret, embarrassment; Eshbaugh & Gute, 2008; Fielder et al., 2014; Grello et al., 2006; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Those interested in interventions to address problems associated with hooking up in college students might consider employing normative feedback, similar to approaches used to challenge normative beliefs about alcohol use (LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, & Pedersen, 2008; Neighbors, Larimer, & Lewis, 2004; Walters, 2000), to correct misperceptions students hold regarding others’ approval of hooking up.

Contrary to previous research demonstrating that family environment (i.e., parent divorce and parent conflict) and parent attitudes have little influence on hooking up (Fielder & Carey, 2010a; Owen et al., 2010), the current findings indicate that college students who perceive their parents to be more approving of hooking up tend to hold more approving attitudes themselves and are more likely to engage in hooking up. These results are more consistent with research demonstrating that perceived parental approval of alcohol use, for example, is positively related to college students’ own approval of alcohol (Hummer, LaBrie, & Ehret, 2013). Indeed, the current findings add to a growing body of research indicating that parents are an influential force on children’s attitudes and behaviors even after they transition to college (Abar & Turrisi, 2008; LaBrie, Hummer, Lac, Ehret, & Kenney, 2011; LaBrie & Sessoms, 2012; Turrisi & Ray, 2010).

While previous research has suggested that parents may be a more influential referent group for females as compared to males (Cail & LaBrie, 2010), the current study suggests that perceptions of parent approval significantly contribute to student hooking up attitudes and indirectly influence hooking up behaviors for both sexes. College wellness personnel who seek to reduce the negative consequences resulting from hooking up on campuses might consider involving parents in their prevention/intervention efforts. Parent-based interventions have shown efficacy in reducing harmful drinking among college students (Ichiyama et al., 2009; Turrisi, Jaccard, Taki, Dunnam, & Grimes, 2001) and may be helpful in the hooking up domain. It is important to note again that students report positive valuations on many hooking up experiences (Lewis et al., 2012; Owen et al., 2010) and that for any harm reduction efforts to be impactful they must speak realistically to this aspect of student experience. Finally, given that overall, students perceived their parents to disapprove of hooking up, but viewed their peers as approving, future research is needed to examine how students deal with these conflicting norms. For example, parents may both directly influence student attitudes, but could also indirectly influence students by moderating the influence of peers on student behaviors (Napper, Hummer, Chithambo, & LaBrie, 2014).

While the overall model showed good fit for both males and females, close friend injunctive norms appeared to be a more important predictor of attitudes and behaviors for males than females. Further, T1 attitudes predicted T2 behaviors for males, but not females. These sex differences may reflect that females’ hooking up behaviors are influenced more strongly by contextual factors (e.g., pressure from partners or alcohol use) than males, and therefore females’ personal attitudes and close friend perceived norms are less influential for predicting future behavior. Indeed, while females were found to be less approving of hooking up than males, there was no significant gender difference in the proportion of students who reported hooking up. This may indicate that females are more likely to hook up even when they are less personally approving. Past research indicates that females are more likely than males to report that they would not have gone as far sexually during a hook up if they had not been drinking alcohol (LaBrie et al., 2014). Further, females often report feeling pressured to engage in unwanted sexual behaviors when describing their worst hooking up experiences (Paul & Hayes, 2002). Although hooking up may be more egalitarian than traditional dating (Bradshaw et al., 2010), it may be that males have more control over decision making and initiation of sexual behaviors than females. Given that females may experiences more negative outcomes as a result of hooking up (Grello et al., 2006; Owen et al., 2010; Paul & Hayes, 2002; Shukusky & Wade, 2012), future research that explicates the situational factors that predict females’ hooking up behaviors may be beneficial.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study had a number of limitations. For example, data collection relied on students’ self-reports of hooking up behavior, which may be subject to self-report biases. In addition, the sample included only college students who reported at least one heavy drinking incident in the past three months. Although examining hooking up attitudes and behaviors among drinkers is relevant given the relationship between alcohol use and hooking up (Fielder & Carey, 2010b; LaBrie et al., 2014; Olmstead, Pasley, & Fincham, 2013), participants in the current sample endorsed more lenient hookup attitudes and behaviors relative to their non-heavy drinking peers. Future studies utilizing nationally representative samples of young adults, including non-heavy drinking samples, are needed to determine if the current findings hold for broader populations.

While the current study did not explore the influence of descriptive norms, perceptions of others’ behaviors are a strong predictor of people’s behaviors (Berkowitz, 2004; Perkins, 2002) and influence students’ hookup behaviors (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013). Therefore, examining the independent influences of injunctive and descriptive norms on hooking up within one model would shed further light on the causal predictors of hookup attitudes and behaviors.

In previous studies, students have provided a variety of definitions for hooking up (Holman & Sillars, 2012; Lewis, Atkins, Blayney, Dent, & Kaysen, 2013). In the current study, students were provided with a standard definition that included a range of sexual behaviors. While using a standard definition allowed us to assess the influence of norms in a consistent way, in future studies it would be useful to explore norms for specific sexual behaviors separately. It may be that students hold a range of attitudes toward different types of hooking up behaviors and perceive their peers and parents to do so too. Further, more specific norms may be better predictors of different types of hooking up behaviors (Barriger & Vélez-Blasini, 2013). Along these lines, although the present study offers important insight into the relationship between norms and hookup behaviors, norms and attitudes were measured using broadly defined, single-item measures. This line of research would benefit from the development of validated multi-item measures of hookup norms, attitudes, and behaviors. Finally, the current study operationalized hookup behaviors as a dichotomous variable. Future studies that examine frequency of hooking up may provide a better understanding of the relationships among hookup-related injunctive norms, attitudes, and behaviors.

Conclusions

The current study extends past research by employing longitudinal data to explore how injunctive norms for three different reference groups relate to student hooking up behavior. While previous research has indicated that injunctive norms may not be an important predictor of hooking up behavior, the current study suggests that perceptions of how approving close friends and parents are toward hooking up can shape personal attitudes and thereby influence future hooking up behaviors. Furthermore, sex weakly moderated the influence of injunctive norms on hooking up attitudes and behaviors, such that males were more strongly influenced by perceived close injunctive norms than females.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants R01AA014576-09 and T32AA007459 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health. Support for Dr. Napper was provided by ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Abar C, Turrisi R. How important are parents during the college years? A longitudinal perspective of indirect influences parents yield on their college teens' alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison R, Risman BJ. A double standard for"hooking up": How far have we come toward gender equality? Social Science Research. 2013;42:1191–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms of alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1994;8:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Barriger M, Vélez-Blasini CJ. Descriptive and injunctive social norm overestimation in hooking up and their role as predictors of hook-up activity in a college student sample. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50:84–94. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2011.607928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz AD. The social norms approach: Theory, research, and annotated bibliography. 2004 Retrieved from http://www.alanberkowitz.com/articles/social_norms.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bogle K. Hooking up: Sex, dating and relationships on campus. New York, NY: New York University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:331–341. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw C, Kahn AS, Saville BK. To hook up or date: Which gender benefits? Sex Roles. 2010;62:661–669. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. London: Routledge; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cail J, LaBrie JW. Disparity between the perceived alcohol-related attitudes of parents and peers increases alcohol risk in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:135–139. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou CP, Bentler PM. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2nd ed. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1990. Model modification in covariance structure modeling. A comparison among likelihood ratio, Lagrange Multiplier, and Wald tests; pp. 115–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JM, Bates SC. Referent group proximity, social norms, and context: Alcohol use in a low-use environment. Journal of American College Health. 2011;59:252–259. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2010.502192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- England P, Shafer EF, Fogarty AC. Hooking up and forming romantic relationships on today’s college campuses. In: Kimmel M, Aronson A, editors. The Gendered Society Reader. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. pp. 531–547. [Google Scholar]

- Eshbaugh EM, Gute G. Hookups and sexual regret among college women. Journal of Social Psychology. 2008;148:77–89. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.148.1.77-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Predictors and consequences of sexual "hookups" among college students: A short-term prospective study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010a;39:1105–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9448-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Carey MP. Prevalence and characteristics of sexual hookups among first-semester female college students. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy. 2010b;36:346–359. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2010.488118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Walsh JL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Predictors of sexual hookups: A theory-based, prospective study of first-year college women. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:1425–1441. doi: 10.1007/s10508-013-0106-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielder RL, Walsh JL, Carey KB, Carey MP. Sexual hookups and adverse health outcomes: A longitudinal study of first-year college women. Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:131–144. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2013.848255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia JR, Reiber C. Hook-up behavior: A biopsychosocial perspective. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. 2008;2:192–208. [Google Scholar]

- Grello CM, Welsh DP, Harper MS. No strings attached: The nature of casual sex in college students. Journal of Sex Research. 2006;43:255–267. doi: 10.1080/00224490609552324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gute G, Eshbaugh EM. Personality as a predictor of hooking up among college students. Journal of Community Health Nurses. 2008;25:26–43. doi: 10.1080/07370010701836385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman A, Sillars A. Talk about "hooking up": The influence of college student social networks on nonrelationship sex. Health Communication. 2012;27:205–216. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2011.575540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, LaBrie JW, Ehret PJ. Do as I say, not as you perceive: Examining the roles of perceived parental knowledge and perceived parental approval in college students' alcohol-related approval and behavior. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2013;13:196–212. doi: 10.1080/15295192.2013.756356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichiyama MA, Fairlie AM, Wood MD, Turrisi R, Francis DP, Ray AE, Stanger LA. A randomized trial of a parent-based intervention on drinking behavior among incoming college freshmen. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supp. No. 2009;16:67–76. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn AS, Fricker K, Hoffman J, Lambert T, Tripp M, Childress K. Hooking up: Dangerous new dating methods?; Washington, D.C. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association.2000. Aug, [Google Scholar]

- Korcuska JS, Thombs DL. Gender role conflict and sex-specific drinking norms: Relationships to alcohol use in undergraduate women and men. Journal of College Student Development. 2003;44:204–216. [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Ghaidarov TM, Lac A, Kenney SR. Hooking up in the college context: The event-level effects of alcohol use and partner familiarity on hookup behaviors and contentment. Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:62–73. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.714010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lac A, Ehret PJ, Kenney SR. Parents know best, but are they accurate? Parental normative misperceptions and their relationship to students' alcohol-related outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:521–529. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Lac A, Lee CM. Direct and indirect effects of injunctive norms on marijuana use: The role of reference groups. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2010;71:904–908. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2010.71.904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Pedersen ER. Live interactive group-specific normative feedback reduces misperceptions and drinking in college students: A randomized cluster trial. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:141–148. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Sessoms AE. Parents still matter: The role of parental attachment in risky drinking among college students. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2012;21:91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert TA, Kahn AS, Apple KJ. Pluralistic ignorance and hooking up. Journal of Sex Research. 2003;40:129–133. doi: 10.1080/00224490309552174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapsley DK, Rice KG, Shadid GE. Psychological separation and adjustment to college. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1989;36:286–294. [Google Scholar]

- Latane B. The psychology of social impact. American Psychologist. 1981;36:343–356. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Atkins DC, Blayney JA, Dent DV, Kaysen DL. What is hooking up? Examining definitions of hooking up in relation to behavior and normative perceptions. Journal of Sex Research. 2013;50:757–766. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.706333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Granato H, Blayney JA, Lostutter TW, Kilmer JR. Predictors of hooking up sexual behaviors and emotional reactions among U.S. college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012;41:1219–1229. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health. 2006;54:213–218. doi: 10.3200/JACH.54.4.213-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. 6th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Hummer JF, Chithambo TP, LaBrie JW. Perceived parent and peer marijuana norms: The moderating effect of parental monitoring during college. Prevention Science. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0493-z. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Larimer ME, Lewis MA. Targeting misperceptions of descriptive drinking norms: Efficacy of a computer-delivered personalized normative feedback intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:434–447. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lostutter TW, Whiteside U, Fossos N, Walker DD, Larimer ME. Injunctive norms and problem gambling among college students. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2007;23:259–273. doi: 10.1007/s10899-007-9059-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, O'Connor RM, Lewis MA, Chawla N, Lee CM, Fossos N. The relative impact of injunctive norms on college student drinking: The role of reference group. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:576–581. doi: 10.1037/a0013043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmstead S, Pasley K, Fincham FD. Hooking up and penetrative hookups: Correlates that differentiate college men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2013;42:573–583. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-9907-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Fincham FD, Moore J. Short-term prospective study of hooking up among college students. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:331–341. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9697-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Fincham FD. "Hooking up" among college students: Demographic and psychosocial correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9414-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, Hayes KA. The casualties of "casual" sex: A qualitative exploration of the phenomenology of college students' hookups. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:639–661. [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, McManus B, Hayes A. "Hookups": Characteristics and correlates of college students' spontaneous and anonymous sexual experiences. Journal of Sex Research. 2000;37:76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Designing alcohol and other drug prevention programs in higher education: Bringing theory into practice. Newton, MA: The Higher Education Center for Alcohol and Other Drug Prevention, U.S. Department of Education; 1997. College student misperceptions of alcohol and other drug use norms among peers: Exploring causes, consequences, and implications for prevention programs; pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins HW. Social norms and the prevention of alcohol misuse in collegiate contexts. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supp. No. 2002;14:164–172. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiber C, Garcia JR. Hooking up: Gender differences, evolution, and pluralistic ignorance. Evolutionary Psychology. 2010;8:390–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukusky JA, Wade T. Sex differences in hookup behavior: A replication and examination of parent-child relationship quality. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. 2012;6:494–505. [Google Scholar]

- Stinson RD. Hooking up in young adulthood: A review of factors influencing the sexual behavior of college students. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy. 2010;24:98–115. [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Jaccard J, Taki R, Dunnam H, Grimes J. Examination of the short-term efficacy of a parent intervention to reduce college student drinking tendencies. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:366–372. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turrisi R, Ray AE. Sustained parenting and college drinking in first-year students. Developmental Psychobiology. 2010;52:286–294. doi: 10.1002/dev.20434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST. In praise of feedback: An effective intervention for college students who are heavy drinkers. Clinical & Program Notes. 2000;48:235–238. doi: 10.1080/07448480009599310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]