Abstract

There are significant discrepancies regarding use of the term “dieting.” Common definitions of dieting include behavior modifications arguably moderate (e.g., increasing vegetable consumption), those considered more extreme (e.g., fasting), and more ambiguous behaviors (e.g., reducing carbohydrates). Adding to confusion are findings demonstrating that many individuals endorsing dieting do not actually reduce caloric intake. (1) Thus, “dieting” refers to behaviors ranging from moderate to extreme, attempts to reduce intake without objective caloric decrease, and caloric reductions without associated distress. Unfortunately, existing measures collapse together these widely discrepant experiences. As a result, there is poor coordination between the eating disorder and obesity fields in terms of dieting recommendations. Some suggest that dieting contributes to development of disordered eating and obesity; others argue that dieting is necessary for reducing excess weight and health risk.

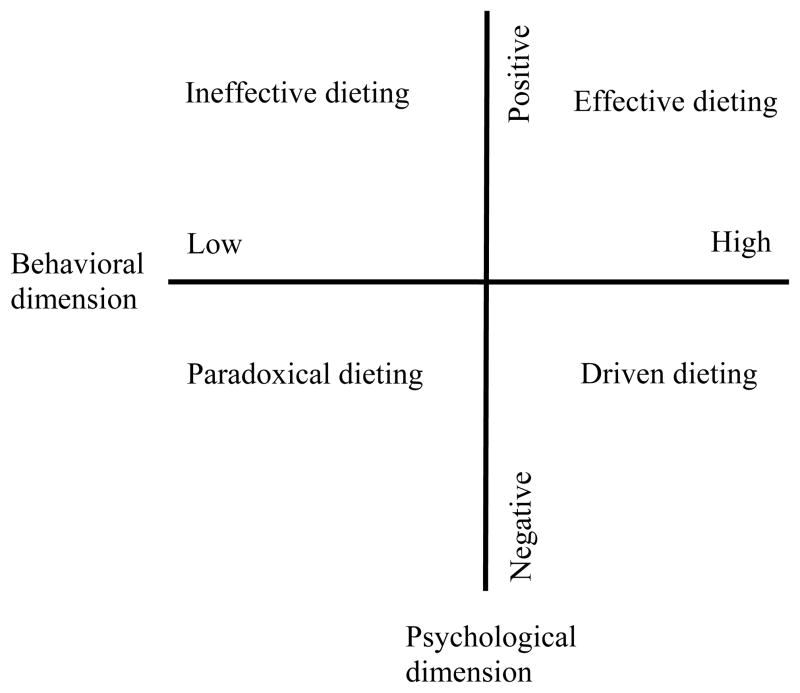

Without clearly defined dieting constructs, neither the eating disorders nor obesity fields can progress towards effective prediction, prevention, or treatment. We propose a novel classification scheme, the “Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm”, which improves upon existing models by differentiating the behavioral and psychological dimensions associated with discrepant dieting experiences and categorizing the interactions between these domains. This model is intended to categorize individuals that endorse dieting, independent of dieting goals. At present, this model is only meant to describe dieting patterns associated with different outcomes, rather than to suggest causal relationships between these patterns and eating disorder and obesity risk. Below we describe this paradigm and provide directions for research.

Dieting Dimensions

The Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm classifies individuals along two separate dimensions: a behavioral dimension and a psychological dimension (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphic representation of the Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm for understanding dieting phenomena

Behavioral Dimension

The behavioral dimension captures all dietary behaviors expected to produce caloric reductions sufficient to alter body shape and/or weight, including both moderate behaviors (e.g., limiting portions) and more extreme dieting behaviors (e.g., fasting). Individuals differ in types of dieting behavior as well as the frequency and duration of dieting, with some engaging in dieting behavior briefly or infrequently and others chronically dieting. Therefore, the behavioral dimension of dieting ranges from low to high according to the likelihood that the type, frequency, and duration of dieting behavior are sufficient to produce weight changes. Table 1 presents examples of behaviors captured within this dimension.

Table 1.

Representative examples of attitudes and behaviors characteristic of each dieting dimension and category within the Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm

| Dieting category | Examples of the behavioral dimension | Examples of the psychological dimension | Case examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Driven dieting |

High on behavioral dimension

|

Negative on psychological dimension

|

John has a strict calorie limit of 1,200 calories/day, which he achieves through eating very small portions of a limited selection of foods. Throughout the day, he has difficulty concentrating because he is anticipating his next meal, yet he feels as though he never enjoys meals because he is so anxious about going over his caloric limit and remains hungry at the end of the meal. Though he has lost considerable weight, he continues to feel unhappy with his body and disappointed with his rate of weight loss. Therefore, at times skips meals or fasts in order to “speed things up”. |

| Paradoxical dieting |

Low on behavioral dimension

|

Negative on psychological dimension

|

Sarah identifies herself as a “chronic dieter”. She has attempted most popular mainstream diets and yet never seems to lose weight. She is currently attempting a new diet, and, as always, has strictly adhered to the rules of the diet for the first few weeks. However, she has not seen the drastic weight loss she has expected, and is frustrated and tired of continually feeling hungry and thinking about food. At her daughter’s birthday party, she “caves” and has a small piece of cake. Afterwards, she feels overwhelmed with guilt and thinks, “I messed up again.” For the next several weeks, she feels angry with herself for her perceived failure and disgusted with her body. She overeats, figuring, “I’ll never be able to stick to a diet anyway.” |

| Effective dieting |

High on behavioral dimension

|

Positive on psychological dimension

|

Beth has been dieting for three months. She started her diet after learning from her doctor that she had developed hypertension, but that lifestyle changes could reverse this condition. Beth is aiming for a moderate weight loss goal of 2 lbs./month and has been delighted as she has surpassed these goals. In order to lose weight, Beth cut out soft drinks and “junk” food, and has begun cooking heart-healthy meals and limiting her portions. She is generally consistent in her eating, however she recently “splurged” when eating out for her anniversary. However, she figured that one meal would not ruin her diet and resumed following her diet plan the next day. |

| Ineffective dieting |

Low on behavioral dimension

|

Positive on psychological dimension

|

Ben notices that he has gained some weight over the winter and thinks that he ought to go on a diet so to better enjoy his preferred summer activities (e.g., hiking, volleyball). Ben decides to cut down on his carbohydrate intake and try to eat more vegetables instead. Though he makes these changes to his diet, they are not enough to support weight loss. He shrugs off his lack of weight loss, stating that he is glad that he is at least eating healthier, and that he will just try to be active early in the summer in order to support his weight loss goals. |

Psychological Dimension

The psychological dimension of dieting consists of emotional, cognitive, and motivational indices that have been associated with dieting and is considered separately from the behavioral dimension of dieting. The psychological dimension is subdivided into two poles characterizing different attitudes towards dieting: a negative psychological approach and a positive psychological approach. Table 1 highlights representative characteristics of the psychological dimension.

The negative pole of the psychological dimension captures psychological approaches to dieting that have been associated with disordered eating and/or poor weight control (2, 3). We have identified three interrelated characteristics comprising the negative psychological dimension: 1) Psychological rigidity: a strict, “all or nothing” dieting mentality; 2) Perceived deprivation: the experience of eating less than desired, independent of amount consumed; and 3) Dieting preoccupation: obsessive focus on food, body shape, and weight.

The positive pole of the psychological dimension involves psychological approaches that have been associated with lower risk for disordered eating and excess weight (2, 4, 5). We have identified three characteristics that comprise the positive psychological dimension: 1) Goal-directedness: focus on working consistently towards specific dietary goals; 2) Dieting flexibility: a conscious, but moderate and accepting attitude towards dieting goals; and 3) Health-focus: prioritizing health-related goals above appearance.

Dieting Categories

Existing dieting models and measures capture some aspects of the psychological and behavioral dimensions of the Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm, however none has clearly differentiated these dimensions as distinct and examined their interactions. In contrast, our model is both dimensional and categorical, allowing for manifestations at different points along the behavioral and psychological axes, but also cross-classifying like individuals according placement along dieting dimension into the following categories: 1) Driven dieting (high on the behavioral dimension, negative on the psychological dimension), 2) Paradoxical dieting (low on the behavioral dimension, negative on the psychological dimension), 3) Effective dieting (high on the behavioral dimension, positive on psychological dimension), and 4) Ineffective dieting (low on the behavioral dimension, positive on the psychological dimension). Representative characteristics comprising each category are listed in Table 1.

Driven Dieting

Driven dieting involves high levels of dieting behavior and a negative psychological approach to dieting (see Figure 1). The clearest, albeit most severe, example of driven dieting can be found in anorexia nervosa, which is predicated on the presence of dieting behavior (i.e., extreme restriction) and negative psychological indices of dieting (e.g., weight and shape preoccupation). However, as Lowe and colleagues have demonstrated (6), individuals of varied weight strata suppress baseline weight through restriction. Individuals within this category may be similar to the “restrained dieters” described by Lowe’s research group (7), who exhibit elevated food cravings, while objectively and consistently engaging in dieting behavior. Prior research suggests that psychological and behavioral characteristics of driven dieting are associated with increased risk for disordered eating (8). There is also evidence that individuals in this category may be at risk of excess weight gain if restriction is relinquished; however, if restriction is persistent, excess gain is not expected (7).

Paradoxical Dieting

Paradoxical dieting involves low dieting behavior and a negative psychological approach to dieting (see Figure 1). Individuals in this category experience negative psychological indices of dieting, but do not engage in behavior sufficient to alter body shape and/or weight. Individuals engaging in paradoxical dieting may nonetheless believe they are restricting because they are eating less than they prefer given an obesity-promoting environment (1). There has been a complex history of attempting to describe the psychological and behavioral patterns characteristic of paradoxical dieting using the term “restraint”. Herman and Polivy’s (9) original conceptualization of “restraint theory” described restrained eaters as individuals with intentions to restrict eating and a tendency to overeat, perhaps resulting from cognitive efforts to control intake. Supporting this theory are prospective studies suggesting that restraint may predict development of eating disorder symptoms, but typically does not negatively correlate with intake (1). However, other studies contradict these findings, suggesting that increased restraint can support healthy weight management and reduce disordered eating (6). These discrepancies likely result from the term “restraint” also describing a range of attitudes and behaviors. For instance, researchers have found that the items comprising certain restraint scales can be broken into categories involving “rigid” and “flexible” restraint, with the former associated with more negative outcomes than the latter (2). According to the Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm, “rigid restraint” items most appropriately capture characteristics of paradoxical dieting, while “flexible restraint” items better capture characteristics of the effective dieting category (described below). Further, Lowe’s conceptualization of “chronic dieters”, characterized by ongoing attempts to diet and frequent disinhibition would subsumed within this category (7).

As indicated by the category’s description, the negative cognitive focus on dieting, coupled with inability to initiate or sustain dieting behavior, may make individuals in the paradoxical dieting category particularly susceptible binge eating and other forms of disordered eating (9). Evidence suggests that such individuals may be able to achieve short-term weight- and shape- related goals, but are ultimately at risk of excess weight gain, possibly mediated through binge eating (7).

Effective Dieting

Effective dieting involves high dieting behavior and a positive psychological approach to dieting (see Figure 1). It is expected that individuals within this category would engage in mostly moderate behaviors to reducing caloric intake (e.g., limiting energy-dense foods, increasing fruit and vegetable consumption) and that more extreme dieting behaviors (e.g., fasting) would be used sparingly by this group and for purposes less rigidly associated with appearance, as the positive psychological approach to dieting would reduce the need for resorting to extremes. However, these assumptions need to be tested.

This category would likely capture the behaviors and attitudes of dietary restraint that have been associated with successful management of weight and body shape and reductions in eating disorder symptoms (2, 6), perhaps explaining some of the discrepancies in the research on restraint. Individuals engaging in patterns characteristic of the effective dieting category have been found to experience positive weight- and shape- related outcomes without developing disordered eating patterns, and, in fact, often derive psychological benefits (e.g., reduced binge eating) from this dieting approach (2, 6).

Ineffective Dieting

Ineffective dieting involves having intentions to diet, and a positive psychological approach to dieting, but engaging in behaviors insufficient to alter body shape and/or weight (see Figure 1). This category captures the many non-disordered individuals struggling to initiate or maintain dieting behaviors, including the majority of overweight individuals attempting weight-loss dieting (6). Individuals with characteristics associated with ineffective dieting have been found to be unsuccessful at either altering weight and body shape or maintaining short-term alterations on these indices (6); however, they are unlikely to be at increased risk of developing disordered eating due to their positive psychological approach to dieting.

Future Directions

The first task for evaluating the utility of the Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm will be developing and testing reliable and valid methodology for assessing each dimension and category. Though existing dieting measures capture some of the aspects of this paradigm, new assessment methodology, perhaps including a behavioral component to assess the behavioral dimension, is needed to more clearly capture the concepts associated with this model. Once reliable and valid methodology for capturing these constructs is established, it will be important to examine the following: 1) Whether behavioral and psychological dieting indices can be separated into distinct dimensions and if these dimensions interact as outlined by the hypothesized categories; 2) Whether positive and negative quadrants of the psychological dimension constitute qualitatively different experiences or gradients along the same process. For instance, rigidity and goal-orientation may describe different gradients of “psychological control,” with rigidity at the extreme end and goal-orientation towards the middle, or may be separate constructs; 3) The ability of this model to identify individuals with elevated eating disorder and/or obesity risk; 4) The temporal relationships between each dieting category and outcomes related to weight and eating disorder symptoms. For instance, it may be that the patterns characteristic of each dieting category directly contribute to relative eating disorder and/or obesity risk, or that these patterns are strategies resulting from pre-existing tendencies towards certain eating- and weight- related outcomes (6); 5) How the dimensions and categories outlined interact with biological consequences of weight loss (e.g., increased metabolic efficiency).

In conclusion, the Psycho-behavioral Dieting Paradigm, a novel model for organizing attitudes and behaviors encompassed within the term “dieting,” can promote greater definitional clarity in dieting research. This can allow more productive dialogue and collaboration between eating disorder and obesity fields and may aid clinicians in identifying individuals at elevated eating disorder and/or obesity risk. Thus, this paradigm can assist in producing more coordinated and effective efforts between two major areas of public health concern.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F31MH097450. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as reflecting the views of USUHS or the U.S. Department of Defense. The authors thank Jackson Coppock and Jackie Hayes for their feedback on this manuscript.

References

- 1.Stice E, Fisher M, Lowe MR. Are dietary restraint scales valid measures of acute dietary restriction? Unobtrusive observational data suggest not. Psychol Assess. 2004;16(1):51–9. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.16.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westenhoefer J, Broeckmann P, Münch AK, Pudel V. Cognitive control of eating behaviour and the disinhibition effect. Appetite. 1994;23(1):27–41. doi: 10.1006/appe.1994.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Timmerman GM, Gregg EK. Dieting, perceived deprivation, and preoccupation with food. West J Nurs Res. 2003;25(4):405–18. doi: 10.1177/0193945903025004006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorin AA, Phelan S, Wing RR, Hill JO. Promoting long-term weight control: does dieting consistency matter? Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28(2):278–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Putterman E, Linden W. Appearance versus health: does the reason for dieting affect dieting behavior? J Behav Med. 2004;27(2):185–204. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000019851.37389.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowe MR, Timko CA. Dieting: really harmful, merely ineffective or actually helpful? Br J Nutr. 2004;92 (Suppl 1):S19–22. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witt AA, Katterman SN, Lowe MR. Assessing the three types of dieting in the Three-Factor Model of dieting. The Dieting and Weight History Questionnaire. Appetite. 2013;63:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Davies BA. Identifying dieters who will develop an eating disorder: a prospective, population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2249–55. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herman CP, Polivy J. Restrained eating. In: Stunkard AJ, editor. Obesity. Philedelphia: WB Saunders; 1980. pp. 208–25. [Google Scholar]