Introduction

The ability to undergo sexual development is ubiquitous throughout eukaryotes. However, the pervasiveness of sexual reproduction is a conundrum in evolution. Sex has intrinsic disadvantages due to associated costs, which include the two-fold cost of sex: two individuals are required to produce progeny, whereas asexual modes of propagation require only a single parent. Other costs involve 1) a diluted transmission of parental genes to the progeny and 2) time and resources it takes to locate a mating partner [1]. Does this say that sex is entirely detrimental? No, in fact, the Red queen hypothesis supports that the benefits of sex, which include adaptation to changes in the environment, tolerance of deleterious mutations, and avoidance of pathogens, are just sufficient to outweigh the costs [2-4].

Sharing a common ancestor with animals as a member of the opisthokont clade of eukaryotes, fungi serve as exemplary models to elucidate the genetics of sex and the evolution of sex determinants and sex chromosomes. Saccharomyces cerevisiae has provided insights to understand mating partner recognition, pheromone responses, and sex-specific transcription factors. In addition, extensive studies on the genetics of sex have been conducted in other ascomycetes and basidiomycetes (dikarya). Although the studies of the dikarya have advanced our understanding of the evolution and the genetics of sex, there are some disadvantages to this more phylogenetically narrow prism; for example, in the fungal kingdom, ascomycetes and basidiomycetes are diverged phyla that are distinctly related from the early divergence point between animals and fungi. Zygomycetes and chytridiomycetes are early diverged fungi, albeit both are polyphyletic [5-7]. Therefore, the early diverged fungi may be uniquely situated to provide novel insights to understand the evolution of the genetics of sex and reveal features that are shared between animals and fungi. However, compared to the dikarya lineages, zygomycetes and chytridiomycetes have received less attention from mycologists. Here, we review the sex locus of the Mucorales that belong to the zygomycetes and the implications of the discovery and features of the sex loci for models on the evolution of sex chromosomes.

Sex and the Mucorales

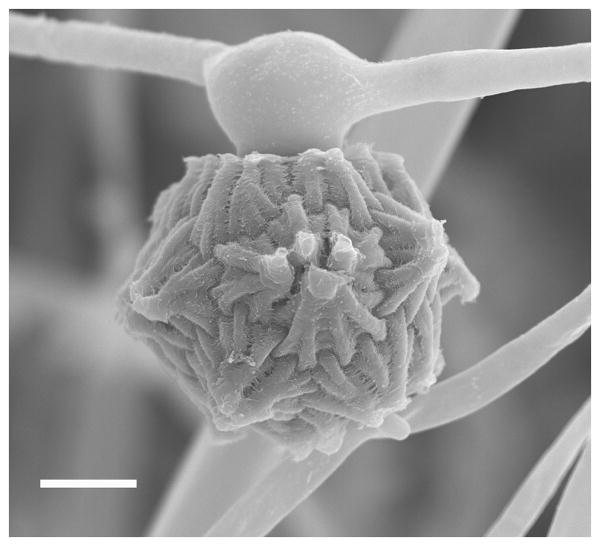

The Mucorales belong to the Zygomycota and the term zygomycetes was named based on their sexual spores, the zygospores, which are large, overt, and macroscopic compared to spores of the dikarya. During the formation of zygospores, two compatible mating type hyphae fuse and form a zygote, which appears similar to the scales of a balance [in Greek, zygos, meaning a balance scale] (Fig. 1) (reviewed in [8]). The zygospores have a prolonged period of dormancy (a month to years) before germinating to produce meiospores. This long period of spore dormancy renders these species less facile genetic model systems. The zygospores germinate to form a single aerial hypha with a sporangium at the apex, which is morphologically similar to the asexual sporangia. The sexual sporangium harbors the meiospores (reviewed in [9]).

Figure 1.

Scanning electron microscopic image of a zygospore of Mucor circinelloides. A zygospore was formed when the strains NRRL3631(+) and CBS277.49(-) were co-cultured on YPD media for 2 weeks at room temperature in the dark. Scale= 10 μm.

Mucorales fungi were first studied as a model for fungal sexual reproduction more than a century ago. For example, heterothallism was first described in a Rhizopus species [10], where hyphal fusion during mating only occurs between two different thalli [from Greek, thallos, meaning a twig]; in contrast, formation of zygospores from a single thallus was referred to as homothallism, first defined for the zygomycete Syzygites megalocarpus [10]. Both terms were then adapted to describe cross-fertility (or opposite-sex mating) and self-fertility in fungi, respectively. Indeed, the first report of sex in fungi was in the Mucoralean species S. megalocarpus in 1820, and early in the 1900s this fungus represented the first homothallic fungal species in the establishment of the terms homothallic and heterothallic [10, 11]. In heterothallic Mucoralean fungi, two mating types are required to complete sexual reproduction. The mating types, plus (+) and minus (-), were assigned arbitrarily in R. nigricans and the designation of mating type in other Mucoralean fungi was based on pairing with the tester (+)/(-) strains of R. nigricans (reviewed in [9]). The two mating types are likely indistinguishable in morphology (isogametic) [7, 10].

Burgeff characterized the first fungal mating pheromone as trisporic acid from Mucor mucedo [12]. Unlike peptide pheromones found in ascomycetes and basidiomycetes, trisporic acid is a volatile organic C18 compound produced from β-carotene [8, 13]. Interestingly, it is thought that trisporic acid can trigger mating in all Mucoralean fungi and Mortierella [9, 14, 15]. Multiple enzymatic steps are required to produce trisporic acids and both mating types must be present in proximity to complete this synthetic process. In both mating types, β-carotene is cleaved into retinol to β-C18-ketone, which is then converted into 4-dihydrotrisporin. From this point, each mating type has a separate pathway to produce trisporic acid [8, 16, 17].

In the (+) mating type, an enzyme converts 4-dihydrotrisporin into 4-dihydromethyl trisporate, which then has to be transferred to the (-) mating type [8]. The 4-dihydromethyl trisporate is then converted into methyltrisporate by 4-dihydromethyltrisporate dehydrogenase (TDH). TDH activity increases only in the sexually stimulated (-) mating type but not in the vegetative (-) mating type, or in the (+) mating type regardless of sexual activation [18]. The (-) mating type cells ultimately produce trisporic acid from methyltrisporate. On the other hand, 4-dihydrotrisporin in the (-) mating type is converted into trisporin and trisporol, both of which have to be transferred to the mating partner. In the (+) mating type cells, the trisporol is then converted into the final product, trisporic acid. The key difference between the (+) and (-) mating type partners during trisporic acid production is the fate of 4-dihydrotrisporin: which is converted into 4-dihydromethyl trisporate in (+) and trisporin in (-) [19]. The 4-dihydrotrisporin-dehydrogenase is a key enzyme, which mediates the conversion of 4-dihydrosporin into trisporin in the (-) mating type cells. Wetzel et al found that the activity of 4-dihydrotrisporin-dehydrogenase is highly upregulated in only the (-) mating type [20].

It is interesting that the two mating types need to cooperate to complete the synthesis of trisporic acid, in which intermediate products must be interchanged. Analogy is also found in the pathway of mating hormone synthesis in the plant pathogens Phytophthora species, where the alpha2 hormone produced by the A2 mating type is transferred to the A1 mating type and serves as a precursor to produce the alpha1 hormone [21]. Convergent evolution may result in an analogous mating pheromone synthetic pathway in the two distantly related lineages [22].

Sex locus of the Mucorales

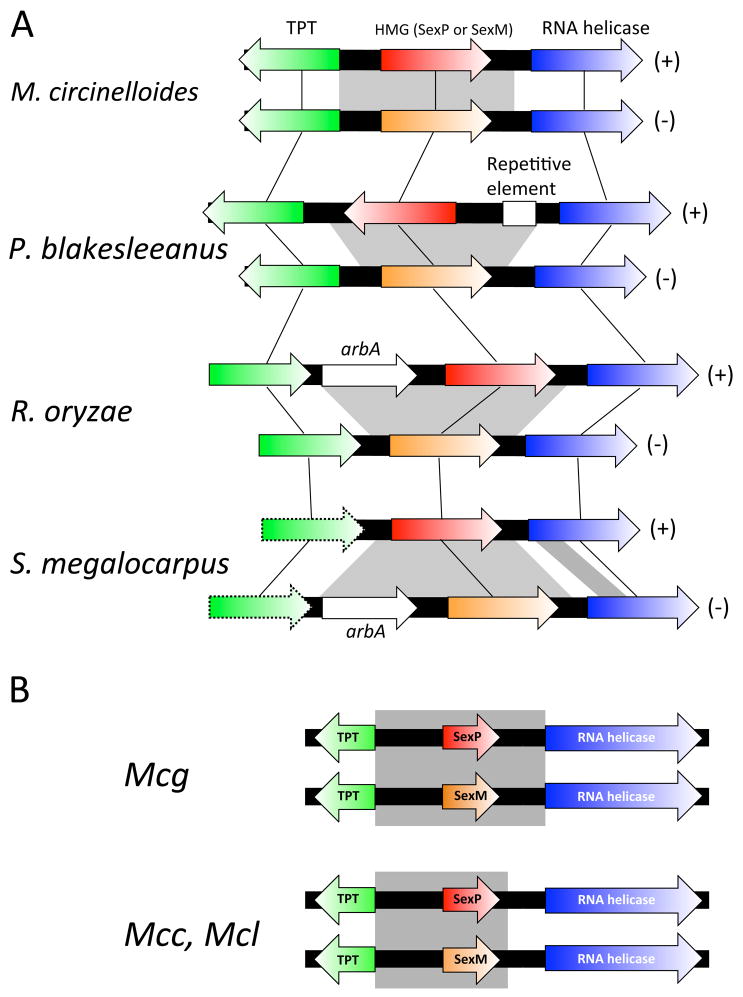

Sexual reproduction is governed by a small region of the genome, called the mating type (MAT) or sex locus in fungi. The MAT locus of a single species comprises two (or more) distinct alleles or idiomorphs and in general encodes key transcription factors, including homeodomain or high-mobility group (HMG) proteins. The sex locus of the Mucorales was first identified in Phycomyces blakesleeanus [23]. Unlike MAT loci in the dikarya, which typically include two or more genes, and in some cases multiple genes in a genomic region spanning >100 kb, the P. blakesleeanus sex locus comprises a single HMG gene. Each mating type encodes an allelic HMG gene, sexP for the (+) and sexM for the (-) mating types, respectively. Both sex genes are flanked by a putative triose phosphate transporter gene (tptA) and RNA helicase gene (rnhA), forming a unique syntenic TPT/HMG/RNA helicase gene cluster (Fig. 2). The study by Idnurm et al. found that the sexP and sexM loci segregate 1:1 following mating, and progeny encoding sexP only mate with isolates with sexM [23]. In addition, sexMΔ mutants of Mucor circinelloides are sterile in any combination of mating with (+) and (-) mating type strains [24]. These results further support that the single HMG gene sex locus controls sexual development in Mucorales.

Figure 2.

sex loci of Mucorales fungi. The sex loci from four different Mucorales fungi are depicted. The (+) sex loci encode sexP gene; (-) sex loci encode the sexM gene, both of which are flanked by conserved tptA and rnhA genes. Noteworthy features are 1) the direction of transcription of the sexP and sexM genes differs in each species; 2) the presence of a repetitive element in the P. blakesleeanus (+) sex locus; 3) the presence of an additional ORF (arbA, encoding an ankyrin-RCC1-BTB-POZ domain protein) in the R. oryzae (+) and S. megalocarpus (-) sex loci; and 4) a partial gene inversion in the rnhA gene of S. megalocarpus. The tptA gene in S. megalocarpus has yet to be sequenced (indicated by dotted outline). Grey boxes indicate the sex locus and gene sizes are not to scale. (B) The sex locus of M. circinelloides f. griseocyanus (Mcg) includes the promoters of the tptA and rnhA genes but the sex loci of M. circinelloides f. circinelloides (Mcc) and M. circinelloides f. lusitanicus (Mcl) include the promoter of the tptA gene but not of the rnhA gene. Grey boxes indicate the sex locus.

A series of studies identified the sex loci in other Mucorales fungi, including M. circinelloides, M. mucedo, R. oryzae, and S. megalocarpus [24-28]. In all cases, the sex loci encode allelic HMG genes: sexP for (+) mating type and sexM for (-) mating type. Interestingly, the two sex genes are differentially regulated: the promoter of the sexP genes in four known Mucorales fungi includes a CCAAT box that is not found in the promoter of the sexM genes [28]. Indeed, sexM is expressed exclusively during mating, whereas sexP is expressed during both vegetative growth and mating. These expression patterns of the two sex gene are concordant across P. blakesleeanus, M. mucedo, and M. circinelloides [23, 28]. Interestingly the SexM protein contains a nuclear localization signal sequence and is localized to nuclei [28]; the localization of SexP has not yet been established. In M. mucedo and M. circinelloides, when the mating pheromone trisporic acid is supplemented during vegetative growth, sexM is expressed at a higher level, which coincides with its expression pattern during mating [28](Lee and Heitman unpublished data). This observation provides a connection between the sex locus and trisporic acid. However, the sex locus and the genes involved in trisporic acid synthesis are unlinked [28] and a direct connection between the sex locus and trisporic acid production is yet to be addressed.

HMG gene(s) may be a sex determinant and function during mating in another basal fungal lineage, the Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF). Rhizophagus irregularis is a plant-associated AMF and its genome encodes at least 76 HMG domain proteins, which were identified based on transcript expression analysis [29]. Subsequent analysis revealed that the genome of R. irregularis encodes 146 HMG gene copies [30]. The AMF have long been known as an asexual fungal lineage; however, the presence of multiple HMG genes in the AMF genome may suggest that bona fide sexual development occurs in this fungal lineage and that the HMGs serve as a sex determinant and play roles in mating. The ascomycete Podospora anserina encodes 12 HMG protein genes, 11 of which are sex determinants or are involved in sexual reproduction [31], suggesting that the HMG genes can be functionally specialized or have been adapted during mating in the fungal lineage, which further supports that the presence of HMG genes can imply the presence of sexual development in the AMF lineage.

Although the RNA helicase gene rnhA flanking the sex genes is highly conserved between the two mating types, there is some evidence that the sex locus can expand to include the rnhA gene (see below). This may indicate that the RnhA helicase functions during mating in the Mucorales, especially in meiotic silencing, which can involve a suppression of expression of unpaired DNAs during mating. In Neurospora crassa SAD-3 is a putative RNA helicase that is a homolog of RnhA. SAD-3 plays a role in meiotic silencing [32]. Schizosaccharomyces pombe Hrr1 is also an RNA helicase homolog and required for RNAi-induced heterochromatin formation [33]. Both SAD-1 and Hrr1 are known to interact with an RNA-directed RNA polymerase and Argonaute [32, 33]. It will be exciting in future studies to explore novel functions of RnhA in transcriptional regulation and/or mating in the Mucorales.

Evolution of the sex locus – what can we learn from the Mucorales

The architecture surrounding the sex locus is characterized as a synteny of genes for TPT/HMG/RNA helicase and the genomes of currently known Mucoralean fungi harbor this synteny. However, the details of the organization of this synteny varies across species (Fig. 2A): 1) for example, in P. blakesleeanus, the sexP and sexM genes are divergently transcribed, whereas they are convergently transcribed in M. circinelloides, M. mucedo, R. oryzae, and S. megalocarpus; 2) the arbA gene is incorporated between the sexP and tptA genes in R. oryzae or between sexM and tptA in S. megalocarpus; 3) a repetitive element is found in the sex locus of the (+) mating type of P. blakesleeanus; and 4) partially divergent rnhA genes are flanked by the sexM and sexP genes in S. megalocarpus. In addition, a comparison of the sex locus within the M. circinelloides subspecies complex revealed that the border of the sex locus spans the promoter of the tptA gene in M. circinelloides f. griseocyanus; on the other hand, the tptA promoter is not part of the sex locus in M. circinelloides f. lusitanicus or M. circinelloides f. circinelloides (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the rnhA gene that flanks the sex locus in S. megalocarpus is adjacent to a glutathione oxidoreductase gene (glrA) that is divergent in the two mating type alleles, in which the (-) sex locus associated glrA is a pseudogene lacking the first 676 bp in the first exon, whereas the (+) sex locus associated glrA gene is intact [27]. Thus, the evolutionary trajectory of the sex locus has been punctuated by gene gain/loss, erosion or expansion of its borders, gene inversions, and invasions by repetitive elements.

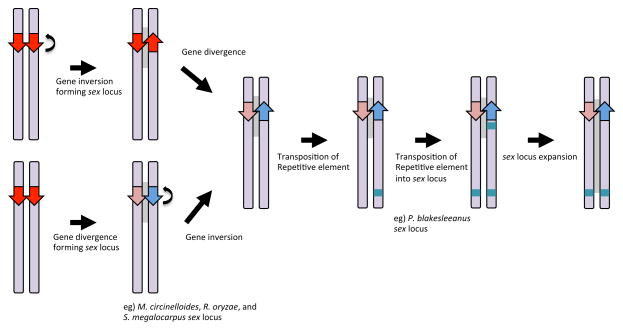

The divergent sex loci found in the Mucoralean fungi support Ohno's hypotheses on early stages and stepwise sex chromosome evolution (Fig. 3) [34]. First, a sex determinant gene arises on an autosomal chromosome. Second, one allele undergoes a gene inversion that suppresses recombination, resulting in a pair of inverted genes that then diverge. The divergently transcribed sexP and sexM genes in P. blakesleeanus provide evidence for this step. The divergent but convergently transcribed sexP and sexM genes in the other Mucorales species may represent another round of gene inversion, or an ancestral step prior to gene inversion [reviewed in [35]]. Third, integration(s) of a repetitive element on the primitive sex chromosome occurs, and the repetitive element is then transposed into one sex allele and additional inversions between the two or more repetitive elements result in expansion of the sex locus throughout a substantial area of the chromosome. These later two steps are largely supported by the findings on the structure of the sex locus of P. blakesleeanus, which harbors a repetitive element in the plus sex locus and two additional elements elsewher the same chromosome on which the sex locus resides. The expansion of the sex locus is also implicated by observations in the other Mucorales species, which include an expansion of the sex locus to include the tptA and rnhA gene promoters in M. circinelloides, a transposition of the arbA gene into the sex locus in R. oryzae and S. megalocarpus (or loss from other species/loci) and diversification of neighboring rnhA genes and a gene encoding glutathione oxidoreductase in S. megalocarpus [27].

Figure 3.

Early steps in sex chromosome evolution. The Mucorales sex locus supports the hypothesis posited by Ohno [34]: a key transcription factor for sex arises on an autosome and one allele undergoes gene inversion followed by gene divergence resulting in divergent alleles (P. blakesleeanus sex locus) (upper). A repetitive element is integrated at the sex locus and elsewhere on the same chromosome (P. blakesleeanus sex locus). The multiple copies of the repetitive element sequence provide templates for recombination and inversion and thereby facilitate the expansion of the sex locus to form a proto-sex chromosome (sex loci of P. blakesleeanus, R. oryzae, and S. megalocarpus). However, allelic sex genes in the same orientation could be an ancestral form, and therefore gene inversion might follow gene divergence (M. circinelloides sex locus) (lower).

The sex locus of the Mucorales provides novel insights to understand sex chromosome evolution, in addition to the MAT loci of the dikarya, which provide insights on partner recognition and mating regulation. Furthermore, both humans and Mucoralean fungi utilize HMG proteins as key transcription factors for sex determination, and thus HMG protein may be ancestral sex determinants.

Mating type and virulence

Mating between two different mating types produces progeny with a 1:1 segregation of both mating types. However, a significant mating type skew is found in pathogenic Mucor species. M. amphibiorum is a causal agent of ulcerative mycosis on platypuses in northern Tasmania in Australia. The isolates from this area mainly represent (+) mating types and, in a toad mucormycosis model, the (+) mating types were more virulent than the (-) mating types [36]. The study found that the (+) mating types of M. amphibiorum caused more severe diseases in toads by producing spherules more rapidly than the (-) mating types. A similar mating type bias was observed in a plant pathogenic Mucorales. M. piriformis causes mucor rot in pear fruit and a study revealed that (+) mating type predominates over (-) mating type in infected plants in Oregon pear orchards [37]. Interestingly, the (+) mating types produced larger lesions than the (-) mating types although both mating types can cause infections under laboratory conditions. In M. circinelloides, (-) mating type isolates tend to produce more virulent, larger spores than (+) mating type isolates, which produce less virulent, smaller spores; however, a subsequent finding suggested that the sexM gene in (-) mating type is not solely responsible for the spore size difference in that sexMΔ mutants still produce larger spores [24]. Spore size could be controlled by SexP, by other genetic loci, or by other genetic loci acting in concert with SexM as a quantitative trait. Analogy is found in the human pathogenic basidiomycete Cryptococcus neoformans, in which the α mating type predominates in clinical and environmental samples (reviewed in [35]).

In C. neoformans, unisexual reproduction explains this mating type bias [38, 39]; however, unisexual reproduction has not been described in the pathogenic Mucorales and currently there is no apparent explanation for the mating type bias in pathogenic Mucor species. Further studies are required to test if mating type is associated with virulence in the Mucorales and the modes of sex determination and sexual reproduction for other species linked animal and plant infections.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID R01 award AI50113-10 to J. H. and NIH/NIAID R21 award AI085331-02 to J. H. and S. L.

References

- 1.Smith JM. The evolution of sex. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stearn SC. The evolution of sex and its consequence. Basel: Birkhaeuser Verlag; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otto SP, Lenormand T. Resolving the paradox of sex and recombination. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:252–61. doi: 10.1038/nrg761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King KC, Delph LF, Jokela J, Lively CM. The geographic mosaic of sex and the Red Queen. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1438–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kwon-Chung KJ. Taxonomy of fungi causing mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis (zygomycosis) and nomenclature of the disease: molecular mycologic perspectives. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:S8–S15. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James TY, Kauff F, Schoch CL, et al. Reconstructing the early evolution of fungi using a six-gene phylogeny. Nature. 2006;443:818–22. doi: 10.1038/nature05110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schussler A, Schwarzott D, Walker C. A new fungal phylum, the Glomeromycota: phylogeny and evolution. Mycol Res. 2001;105:1413–21. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wostemeyer J, Schimek C. Trisporic acid and mating in zygomycetes. In: Heitman J, Kronstad JW, Taylor JW, Casselton LA, editors. Sex in fungi. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idnurm A, James TY, Vilgalys R. Sex in the rest: mysterious mating in the Chytridiomycota and Zygomycota. In: Heitman J, Kronstad JW, Taylor JW, Casselton LA, editors. Sex in fungi. ASM Press; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blakeslee AF. Sexual reproduction in the Mucorineae. Proc Am Acad Arts Sci. 1904;40:205–319. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrenberg CG. Syzygites, eine neue Schimmelgattung, nebst Beobachtungen uber sichtbare Bewegung in Schimmeln. Verhandl Gesamte Naturf Freunde, Berlin. 1820;1:98–109. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burgeff H. Untersuchungen über Sexualitat und Parasitismus bei Mucorineen. Verlag von Gustav Fischer; 1924. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tagua VG, Medina HR, Martin-Dominguez Rl, et al. A gene for carotene cleavage required for pheromone biosynthesis and carotene regulation in the fungus Phycomyces blakesleeanus. Fungal Genet Biol. 2012;49:398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schimek C, Wostemeyer J. Biosynthesis, extraction, purification, and analysis of trisporoid sexual communication compounds from mated cultures of Blakeslea trispora. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;898:61–74. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-918-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schimek C, Kleppe K, Saleem A-R, Voigt K, Burmester A, W√∂stemeyer J. Sexual reactions in Mortierellales are mediated by the trisporic acid system. Mycol Res. 2003;107:736–47. doi: 10.1017/s0953756203007949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ellenberger S, Schuster S, Wostemeyer J. Correlation between sequence, structure and function for trisporoid processing proteins in the model zygomycete Mucor mucedo. J Theor Biol. 2013;320:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Werner S, Schroeter A, Schimek C, Vlaic S, Wostemeyer J, S S. Model of the synthesis of trisporic acid in Mucorales showing bistability. IET Syst Biol. 2012;6:207–14. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb.2011.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schimek C, Petzold A, Schultze K, et al. 4-Dihydromethyltrisporate dehydrogenase, an enzyme of the sex hormone pathway in Mucor mucedo, is constitutively transcribed but its activity is differently regulated in (+) and (-) mating types. Fungal Genet Biol. 2005;42:804–12. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahadevan Y, Richter-Fecken M, Kaerger K, Voigt K, Boland W. Early and late trisporoids differentially regulate beta-carotene production and gene transcript levels in the Mucoralean fungi Blakeslea trispora and Mucor mucedo. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:7466–75. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02096-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wetzel J, Scheibner O, Burmester A, Schimek C, Wostemeyer J. 4-Dihydrotrisporin-dehydrogenase, an enzyme of the sex hormone pathway of Mucor mucedo: purification, cloning of the corresponding gene, and developmental expression. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:88–95. doi: 10.1128/EC.00225-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojika M, Molli SD, Kanazawa H, et al. The second Phytophthora mating hormone defines interspecies biosynthetic crosstalk. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:591–3. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SC, Ristaino JB, Heitman J. Parallels in intercellular communication in oomycete and fungal pathogens of plants and humans. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003028. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Idnurm A, Walton FJ, Floyd A, Heitman J. Identification of the sex genes in an early diverged fungus. Nature. 2008;451:193–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li CH, Cervantes M, Springer DJ, et al. Sporangiospore size dimorphism is linked to virulence of Mucor circinelloides. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002086. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee SC, Corradi N, Byrnes EJ, et al. Microsporidia evolved from ancestral sexual fungi. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1675–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gryganskyi AP, Lee SC, Litvintseva AP, et al. Structure, function, and phylogeny of the mating locus in the Rhizopus oryzae complex. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e15273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Idnurm A. Sex determination in the first-described sexual fungus. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:1485–91. doi: 10.1128/EC.05149-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wetzel J, Burmester A, Kolbe M, Wostemeyer J. The mating-related loci sexM and sexP of the zygomycetous fungus Mucor mucedo and their transcriptional regulation by trisporoid pheromones. Microbiology. 2012;158:1016–23. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.054106-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riley R, Charron P, Idnurm A, et al. Extreme diversification of the mating type–high-mobility group (MATA-HMG) gene family in a plant-associated arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. New Phytol. 2013;201:254–68. doi: 10.1111/nph.12462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tisserant E, Malbreil M, Kuo A, et al. Genome of an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus provides insight into the oldest plant symbiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:20117–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313452110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ait Benkhali J, Coppin E, Brun S, et al. A network of HMG-box transcription factors regulates sexual cycle in the fungus Podospora anserina. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammond TM, Xiao H, Boone EC, Perdue TD, Pukkila PJ, Shiu PKT. SAD-3, a putative helicase required for meiotic silencing by unpaired DNA, interacts with other components of the silencing machinery. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics. 2011;1:369–76. doi: 10.1534/g3.111.000570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motamedi MR, Verdel A, Colmenares SU, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell. 2004;119:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohno S. Sex chromosomes and sex-linked genes. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee SC, Ni M, Li W, Shertz C, Heitman J. The evolution of sex: a perspective from the fungal kingdom. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74:298–340. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00005-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stewart NJ, Munday BL. Possible differences in pathogenicity between cane toad-, frog- and platypus-derived isolates of Mucor amphibiorum, and a platypus-derived isolate of Mucor circinelloides. Med Mycol. 2005;43:127–32. doi: 10.1080/13693780410001731538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Michailides TJ, Spotts RA. Mating types of Mucor piriformis isolated from soil and pear fruit in Oregon orchards (on the life history of Mucor piriformis) Mycologia. 1986;78:766–70. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin X, Hull CM, Heitman J. Sexual reproduction between partners of the same mating type in Cryptococcus neoformans. Nature. 2005;434:1017–21. doi: 10.1038/nature03448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fraser JA, Giles SS, Wenink EC, et al. Same-sex mating and the origin of the Vancouver Island Cryptococcus gattii outbreak. Nature. 2005;437:1360–4. doi: 10.1038/nature04220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]