Abstract

Gingival hyperpigmentation is a major esthetic concern for many people. Although it is not a medical problem, many people complain of dark gums as unesthetic. Gingival depigmentation is a periodontal plastic surgical procedure, whereby the hyperpigmentation is removed or reduced by various techniques. For depigmentation of gingival, different treatment modalities have been reported, such as scalpel, cryosurgery, electrosurgery, lasers, etc., this article compares the management of three cases with scalpel and cryosurgery and also highlights the relevance of cryosurgery.

Keywords: Cryosurgery, electro surgery, gingiva, lasers, melanin, pathologic, physiologic, pigmentation

Introduction

Gingival melanin pigmentation occurs in all races.[1] Melanin, a brown pigment, is the most common natural pigment contributing to endogenous pigmentation of gingiva and also the gingiva is the most predominant site of pigmentation on the mucosa. Melanin pigmentation is the result of melanin granules produced by melanoblasts intertwined between epithelial cells at the basal layer of gingival epithelium.[2]

In some populations, gingival hyperpigmentation is seen as a genetic trait irrespective of age and gender; hence it is termed physiologic or racial gingival pigmentation.[1,3] The degree of melanin pigmentation varies from one individual to another, which is mainly due to the melanoblastic activity.[4] Gingival melanin pigmentation is symmetric and persistent which does not alter the normal gingival architecture. Also, gingival melanosis is frequently encountered among dark-skinned ethnic groups, as well as in medical conditions such as Addison's syndrome, Peutz-Jegher's syndrome, and Von Recklinghausen's disease (neurofibromatosis).[5]

Earlier studies have shown that no significant difference exists in the density of distribution of melanocytes between light-skinned and dark-skinned, and black individuals. However, melanocytes of dark-skinned and black individuals are uniformly highly reactive than in light-skinned individuals.[6]

Gingival depigmentation is a periodontal plastic surgical procedure whereby the hyperpigmentation is removed or reduced by various techniques. The patient demand for improved esthetics is the first and foremost indication for depigmentation. Various depigmentation techniques have been employed. Selection of the technique should be based on clinical experiences and individual preferences. One of the first and still popular techniques to be employed is the surgical removal of undesirable pigmentation using scalpels.[7] There is only limited information in the literature on the depigmentation using surgical techniques. The procedure essentially involves surgical removal of gingival epithelium along with a layer of the underlying connective tissue and allowing the denuded connective tissue to heal by secondary intention. The new epithelium that forms is devoid of melanin pigmentation.[7]

Methods aimed at removing the pigment layer:[7]

Surgical method of de-pigmentation.

Scalpel surgical technique

Cryosurgery

Electrosurgery

-

Lasers.

- Neodymium; aluminum-Yttrium-Garnet (Nd-YAG) laser

- Erbium-YAG lasers

- Carbon-di-oxide CO2 laser.

Chemical methods of de-pigmentation.

Methods aimed at masking the pigmented gingiva with grafts from less pigmented area.

Free gingival graft

Acellular dermal matrix allograft.

This article demonstrates a comparative evaluation of managing gingival pigmentation using scalpel and cryosurgery techniques with 1-month follow-up.

Case Reports

Case 1

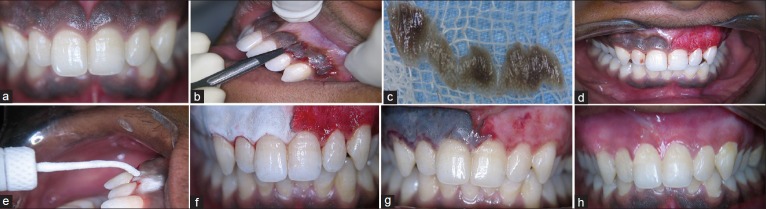

A 23-year-old male patient visited the Department of Periodontology, complaining of dark gums. History revealed that it was present since childhood suggestive of physiological melanin pigmentation [Figure 1a]. Patient was systemically healthy without any habits. Patient's oral hygiene was good. Patient was explained about the treatment options available and the possibility of repigmentation after certain period. Phase I therapy was carried out during the initial visit. A split mouth approach comparing scalpel technique with that of cryosurgery was planned. Local infiltration of lignocaine was administered. At the maxillary left anterior region from central incisor to canine (anterior esthetic segment), a conventional/traditional technique was used, wherein a #15 blade is used for depigmentation [Figure 1b–d].

Figure 1.

Case II: Preoperative (a) case I: Preoperative, (b) depigmentation using scalpel technique, (c) excised specimen, (d) immediate postoperative, (e) depigmentation using cryosurgery technique, (f) the frozen site thawed spontaneously within 1 min, (g) ghosting effect (2nd day), (h) postoperative 4 weeks follow-up

At the right counterpart, cryosurgery technique was used for depigmentation [Figure 1e–g]. There was absolutely no bleeding during the procedure. Postoperative instructions were given to the patient, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory in the form of diclofenac sodium was given thrice daily for 3 days. Patient was recalled after 1-week for re-evaluation. Wound healed uneventfully on both the sides.

Patient experienced pain on the scalpel treated site for 3 days postoperatively.

After 1-week, the pack was removed, and the surgical area was examined. On 1-month postoperative follow-up, the healing was uneventful without any postsurgical complications. The gingiva appeared pink, healthy, and firm giving a normal appearance [Figure 1h]. The patient was very impressed with such a pleasing esthetic outcome. Depigmentation was not carried out for mandibular anterior region because they were of no esthetic concern for the patient.

Case 2

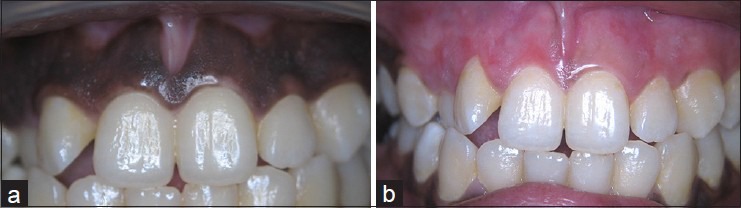

An 18-year-old female had a chief complaint of black gingiva [Figure 2a]. The procedures were performed with the same method as described in the previous case. The wound healed well after 2 weeks. No pain or bleeding complications were found. The gingiva became pink and healthy within 4 weeks [Figure 2b].

Figure 2.

(a) Case II: Preoperative, (b) case II: Postoperative 4 weeks follow-up

Case 3

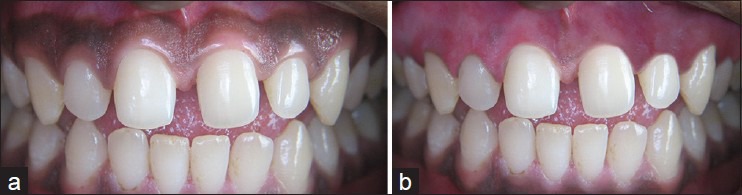

A 21-year-old female had a chief complaint of black gingiva [Figure 3a]. The procedures were performed with the same method as in the previous case. The wound healed well after 4 weeks. No pain or bleeding complications were found. The gingiva became pink and healthy within 4 weeks [Figure 3b].

Figure 3.

(a) Case III: Preoperative, (b) postoperative 4 weeks follow-up

Results

In all the above three cases, no postoperative pain, hemorrhage, infection or scarring occurred in any of the sites on the first and subsequent visits. The healing was uneventful. The patient's acceptance of the procedure was good, and the results were excellent, as perceived by the patient. The follow up period showed no repigmentation.

Discussion

Scalpel surgical technique

One of the first, and still popular, techniques to be employed was the surgical removal of undesirable pigmentation using scalpels. The procedure essentially involves surgical removal of gingival epithelium along with a layer of the underlying connective tissue and allowing the denuded connective tissue to heal by secondary intention. The new epithelium that forms is devoid of melanin pigmentation.[7]

An attempt was made to remove gingival pigmentation surgically on the maxillary left quadrant of the patient. In this particular case, the scalpel method of depigmentation gave satisfactory results from both clinical and patients point of view. However, scalpel surgery causes unpleasant bleeding during and after the operation, and it is necessary to cover the surgical site with periodontal dressing for 7–10 days. The area healed completely in 10 days with normal appearance of gingival. We found that the scalpel technique was relatively simple and versatile and that it required minimum time and effort.

Cryosurgery technique

Cryosurgery is that branch of therapeutics that makes use of local freezing for the controlled destruction or removal of living tissues.

Cryosurgery

The effect of low temperature on living tissues has been the subject of fascinating studies since Robert Boyle reported almost 300 years ago that cells were killed by freezing. The biologic effect of physical factors such as cold behaves like ionizing radiation and the maximum lethal effect is obtained when they are applied to cells undergoing mitosis. Most vital tissues freeze at approximately −2°C, Ultra low temperature (below −20°C) results in total cell death.[8]

The cryogens

Cryogen is a substance used for cryosurgery. Over the years, several cryogens have been used. They include the following. Cryogen effective temperature: Salt ice −20°C, CO2 slush −20°C, fluorocarbons (Freons) −30°C, nitrous oxide −75°C, CO2 snow −79°C, liquid nitrogen −20°C (Swab) −196°C (Spray), tetrafluoroethane (TFE) −20°C to −40°C.[9]

A colorless, nonchlorofluorocarbon, nonflammable gas, 1, 1, 1, 2 TFE is usually used as a coolant or refrigerating systems and electronic circuits. There are human and animal toxicology studies evaluating the safety of TFE.[10,11]

Cryosurgical procedure

The dose of cryogen and the choice of delivery method depend on the size, tissue type, and depth of the lesion. The area of the body on which the lesion is located, and the required depth of freeze also should be considered. Additional patient factors to consider includes the thickness of the epidermis and underlying structures, the water content of the skin, and local blood flow.[12]

Dipstick method

Spray technique

Cryoprobe technique.

Spray technique using spray tip

This is also known as open-spray technique. The hand held or table top cryosurgical unit filled with liquid nitrogen is used, select a spray tip that sprays within the border of the lesion. For single short freeze, no local anesthesia is required. But if the lesion is large and requires more freeze time, then 1% lignocaine is given. The spray tip is held 1 cm away from the lesion, and a steady spray of liquid nitrogen is directed at the center of the lesion. Freeze time commences once the solid ice has formed over the entire area. The lesion is allowed to thaw slowly that is, come back to room temperature. Thaw time is usually double of freeze time.

Cryoprobe technique

In this technique, liquid nitrogen is circulated so as to cool the tip of the cryoprobe, which is to be applied to the lesion. Hence, freezing occurs by conduction. This technique is slower than spray technique. The depth of penetration of the ice ball is difficult to estimate, and prolonged freezing could cause excessive tissue destruction.[13]

The shelf life of liquid nitrogen is not adequate for storage for long periods due to its faster rate of evaporation even in a closed container. Discomfort like stinging, burning sensation or pain (on prolonged freezing) is experienced during the procedure.

Clinical changes following cryosurgery

The tissue freezes solid taking on the appearance of a ball of ice. Thawing occurred in 15–20 s with progression from the periphery to the center of the ice ball. At 12 h an elevated white fluid filled blister appeared which increased in size slightly up to 24 h. The roof of the blister area consisted of a white membrane, outlined by an indistinct red halo. At 48 h the blister ruptured, exposing a smooth underlying surface. At the periphery, the ragged blister membrane remains discernible. Repair and reepithelization take place deep to the slough, which separates off after leaving a clean surface.[14]

In 1970 Mayer et al.[8] conducted a clinical study to evaluate the histological reaction of clinically normal gingiva to freezing. They observed unusual multinucleated giant cells in the epithelium near the periphery of the frozen area after 12 h. They also found that surface repair was completed between 24 and 48 h of injury.

Tal et al.[12] selectively treated epithelium on gingival flap surface by ultra low temperature for 5 s using a gas expansion cryoprobe cooled to −81°C. The authors concluded that the low cryodose can effectively destroy oral gingival epithelium without causing significant morphologic damage to the underlying lamina propria.

In a 2–5 years clinical observation by Tal et al.[12] after superficial cryosurgical treatment of moderate to heavy pigmented gingival in seven nonsmoking patients, the sites were exposed to a gas expansion cryoprobe cooled to −81°C for 10 s. Patients did not report side effects, nor did they require additional treatment during the 5 years period after surgery.

In a simple and effective cryosurgical technique to eliminate the pigmentation Yeh[15] in subjects of abnormal deposition of melanin in gingiva in 20 patients with dark gingiva were treated by direct application of liquid nitrogen with a cotton swab for 20–30 s. The treated gingiva appeared normal within 1–2 weeks after one or two cryosurgical treatments, the acceptance of the treatment was excellent. This was a simple, bloodless cryosurgery for the depigmentation of gingiva, requiring no local anesthesia or sophisticated equipment.

Arikan and Gürkan[16] used TFE cooled cotton swab application in the cryosurgical depigmentation of gingiva. He concluded that TFE may be used as an off-label product with minor complications in melanin depigmentation of gingiva. Sheetra et al.[14] performed gingival cryosurgery in segments in the maxillary anteriors, each segment measuring ~ 5 mm × ~5 mm was exposed to a gas expansion cryoprobe using nitrous oxide, and the cryoprobe was cooled to −70°C to − 90°C for 30 s. Immediately after removal of the cryogenic probe, the tissue was frozen solid, taking on the appearance of a ball of ice. Thawing occurred in 15–20 s with progression from the periphery to the center of the ice ball. 30 min after freezing, the tissue area was indiscernible from adjacent gingiva.

Certain precautions need to be undertake including the prevention of loss of gas attributable to leakage and evaporation, and risk of accident during storage.

In the present case, the cryosurgical procedure was acceptable to the patient because it was not time-consuming. The patient was comfortable because the procedure caused minimal pain, and there was an absence of postoperative pain and hemorrhage. It is imperative to note the need to elucidate the findings of the present case by comparing it to a larger sample size of patients. Hence, additional studies of these variables, with larger sample sizes at histologic and histochemical levels to evaluate the activity and behavior of melanocytes after the cryosurgical procedures, are needed to validate the present findings.

The present case report demonstrates that the application of cryosurgery appears to be a simple, time-efficient, cost effective, and minimally invasive alternative procedure for gingival melanin depigmentation and the esthetic outcome may be maintained. Cryosurgery can be used repeatedly and safely even where surgery is contraindicated as this procedure eliminates the use of a scalpel. Therefore, cryosurgery offers a practical technique to improve patient esthetics.

Conclusion

Based on the available literature, gingival melanin pigmentation can vary depending on whether it is physiological or pathological, based on the location, color or it can be traumatic. The most important factor for determining the treatment for gingival melanin pigmentation is the type of pigmentation, patient acceptance of treatment procedure, its prevalence and its esthetic importance depending on the skin complexion of the patient.

Treatment of the melanin pigmentation using older methods like gingival abrasion, scalpel depigmentation, free gingival graft were time consuming, painful, required placement of periodontal dressings, uneven treated areas and showed results for only a short period of time than cryosurgery or lasers, which shows better results and faster outcome with minimal postoperative complications. Future shows bright outcome for the selection criteria for depigmentation in terms of cryosurgery. Both the procedures are better for depigmentation procedure whilst cryosurgery being slightly better than the scalpel technique for depigmentation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Dummett CO. Oral pigmentation. First symposium of oral pigmentation. J Periodontol. 1960;31:356–60. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciçek Y, Ertas U. The normal and pathological pigmentation of oral mucous membrane: A review. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003;4:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dummett CO, Barens G. Oromucosal pigmentation: An updated literary review. J Periodontol. 1971;42:726–36. doi: 10.1902/jop.1971.42.11.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perlmutter S, Tal H. Repigmentation of the gingiva following surgical injury. J Periodontol. 1986;57:48–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.1986.57.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1984. Text Book of Oral Pathology; pp. 89–136. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabó G, Gerald AB, Pathak MA, Fitzpatrick TB. Racial differences in the fate of melanosomes in human epidermis. Nature. 1969;222:1081–2. doi: 10.1038/2221081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roshna T, Nandakumar K. Anterior esthetic gingival depigmentation and crown lengthening: Report of a case. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:139–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayers PD, Tussing G, Wentz FM. The histological reaction of clinically normal gingiva to freezing. J Periodontol. 1971;42:346–52. doi: 10.1902/jop.1971.42.6.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop K. Treatment of unsightly oral pigmentation: A case report. Dent Update. 1994;21:236–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ellis MK, Gowans LA, Green T, Tanner RJ. Metabolic fate and disposition of 1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane (HFC134a) in rat following a single exposure by inhalation. Xenobiotica. 1993;23:719–29. doi: 10.3109/00498259309166779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Emmen HH, Hoogendijk EM, Klöpping-Ketelaars WA, Muijser H, Duistermaat E, Ravensberg JC, et al. Human safety and pharmacokinetics of the CFC alternative propellants HFC 134a (1,1,1,2-tetrafluoroethane) and HFC 227 (1,1,1,2,3,3, 3-heptafluoropropane) following whole-body exposure. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2000;32:22–35. doi: 10.1006/rtph.2000.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tal H, Landsberg J, Kozlovsky A. Cryosurgical depigmentation of the gingiva. A case report. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:614–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1987.tb01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraser J, Gill W. Observations on ultra-frozen tissue. Br J Surg. 1967;54:770–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800540907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheetra KA, Joann PG, Prabhuji MLV, Lazarus Flemingson. Cryosurgical treatment of gingival melanin pigmentation- A 30 month follow up case report. Clin Adv Perio. 2012;2:73–78. doi: 10.1902/cap.2011.100007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yeh CJ. Cryosurgical treatment of melanin-pigmented gingiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:660–3. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90199-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arikan F, Gürkan A. Cryosurgical treatment of gingival melanin pigmentation with tetrafluoroethane. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:452–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]