Abstract

The aim of this prospective phase II trial was to determine the safety and efficacy of a nonmyeloablative (NMA) conditioning program incorporating peri-transplant-rituximab in patients with CD20+ B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (B-NHL) receiving an allogeneic stem cell transplant (allo-SCT). Fifty-one adult B-NHL patients, with a median age of 54 years, were treated with cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and 200 cGy of total body irradiation (TBI). Rituximab 375 mg/m2 was given on d-8 and in 4 weekly doses beginning d+21. Equine anti-thymocyte globulin (eATG) was given to recipients of volunteer unrelated donor grafts. Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporine and mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus, sirolimus and methotrexate in 8 and 43 patients respectively. Thirty-three patients received grafts from unrelated donors and 18 received grafts from matched related donors. All patients engrafted. Full donor chimerism in bone marrow and peripheral T cells was seen in 92% and 89% of patients respectively at 3 months post-allo-SCT. The cumulative incidence (CI) of grade II-IV acute GVHD (aGVHD) at 6-months was 25% (95% CI: 13-38%) and grade III-IV was 11% (95% CI: 2-20%). The 2-year CI of chronic GVHD (cGVHD) was 29% (95% CI: 15-44%). The 2-year event-free (EFS) and overall (OS) survival for all patients was 72% (95% CI: 59-85%) and 78% (95% CI: 66-90%) respectively. The 2-year EFS for chemosensitive patients was 84% (95% CI: 72- 96%) compared to 30% (95% CI: 2 - 58%) for chemorefractory patients pre-allo-SCT (p<0.001). This NMA regimen, with peri-transplant rituximab, is safe and effective in patients with B-NHL.

Introduction

Despite recent advances, most notably integration of anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (1-4); patients with indolent histology B-NHL and those with aggressive histology B-NHL who have failed high-dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation (HDT-ASCT), are considered incurable with combination chemotherapy alone. While HDT-ASCT remains the standard of care for relapsed and refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) (5), a recent large multi-center prospective study presented data wherein the majority of patients either fail to undergo, or relapse following HDT-ASCT by intent-to-treat analysis (6). Additionally, while HDT-ASCT has provided prolonged remissions for patients with mantle-cell lymphoma (MCL) (7, 8) and follicular lymphoma (FL) (9), it is still considered non-curative and concerns of additive toxicity, including myelodysplasia, remain (10).

Previously, allo-SCT with myeloablative conditioning (MAC) had demonstrated favorable NHL disease control at the expense of prohibitively high transplant-related mortality (TRM) (11, 12). More recently, reduced-intensity (RIC) and NMA conditioned allo-SCT has offered favorable NHL control, attributable to graft-versus-lymphoma (GVL) effect (13, 14) and reduced TRM (15-23). This has permitted extension of allo-SCT to older and more comorbid patients. M.D. Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) have previously introduced monoclonal antibody therapy with rituximab in patients with FL undergoing a NMA allo-SCT, predominately from matched siblings, preceded by chemotherapy only conditioning of fludarabine and cyclophosphamide with encouraging progression-free survival (19). Herein, we present results of a phase II study investigating the integration of rituximab peri-allo-SCT from HLA-matched related and unrelated donors following NMA conditioning with low-dose total body irradiation (TBI) for patients with B-NHL.

Patients and Methods

This was a single center, prospective phase II clinical trial MSKCC Internal Review Board #06-150. All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with federal, local, and institutional guidelines. Rituximab was provided by Genentech, Inc.

Study Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the efficacy of this regimen according to EFS at 1 year post-allo-SCT in patients with B- NHL. EFS was defined as the time from day of transplant to death from any cause, disease progression (POD) beyond the pre-allo-SCT disease staging or the last follow-up. The secondary objectives included safety endpoints of: toxicity, engraftment, aGVHD, cGVHD, TRM, opportunistic infections, and OS.

Patient Eligibility

Eligible patients were 18-70 years of age, had relapsed or primary refractory B-NHL and/or ineligible for a MAC allo-SCT secondary to either: physician choice, advanced age, poor performance status, end-organ insufficiency, significant comorbidities, or recent HDT-ASCT. Patients were also required to have a: creatinine clearance ≥ 50 cc/minute, total bilirubin < 2.5 mg/dL in the absence of Gilbert's syndrome or congenital hyperbilirubinemia, AST and ALT ≤ 3× upper limit of normal, resting left ventricular ejection fraction of ≥ 40%, adjusted diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide ≥ 50%, albumin ≥ 2.5 mg/dL and a Karnofsky performance status ≥ 70%. Enrollment required histologic verification of CD20+ B-NHL on biopsy within one year of allo-SCT. There was no limit to number of prior lines of therapy. Key exclusion criteria included: active, uncontrolled infection, seropositivity for HIV, hepatitis B core antibody or hepatitis C and prior allo-SCT. Patients with aggressive histology BNHL by WHO criteria were required to demonstrate chemosensitivity, either complete (CR, CRu) or partial (PR) remission, to salvage therapy as determined by International Working Group Criteria (24) prior to allo-SCT. They had to be ineligible to proceed to HDT-ASCT because of either: disease involving bone marrow, inability to successfully harvest ≥ 2 × 106 CD34+ stem cells/kg or physician decision. Patients with indolent histology B-NHL, including chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), had to have previously failed at least one line of combination chemotherapy, though chemosensitivity was not required. Patients with MCL were eligible in CR or PR if primary histology was either blastoid histology or p53 expressing on immunohistochemistry. Chemosensitivity was assessed per standard criteria for B-NHL (24) as well as additional criteria for CLL/SLL (25) prior to allo-SCT. The hematopoietic comorbidity index (HCT-CI) (26) was retrospectively determined for each patient. Patients required a fully matched or single HLA allele disparate related or unrelated donor at 10-loci (HLA-A, HLA-B, HLA-C, HLA-DRβ or HLA-DQ). The trial is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00425802).

Treatment and Source of Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Rituximab at 375 mg/m2 was administered day −8 or −7 prior to allo-SCT, given the sensitizing effect of rituximab on B-NHL to cytotoxic chemotherapy (27, 28). Cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg was administered for one dose on day −6 followed by fludarabine at 25 mg/m2 was administered intravenously daily from day −6 to day −2. One dose of TBI at 200 cGy was delivered on day −1. Equine ATG 30 mg/kg was given intravenously daily on day −3 and day −2 to recipients of HLA-matched unrelated or HLA-single allele disparate allografts. Post-allo-SCT patients received rituximab 375 mg/m2 weekly for 4 doses beginning day +21 +/−2 days. The rationale of administration and timing of post-allo-SCT rituximab included both B-NHL progression-free survival benefit in chemotherapy-only programs (29, 30), as well as the kinetics of cellular effector elements, such as NK cells, (31) serving as potential mediators of antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) (32) toward the goal of providing enhanced B-NHL disease control. Peripheral blood hematopoietic stem cells from healthy donors were collected using G-CSF 10 mcg/kg daily for at least 5 days with a targeted CD34+ cell dose of 5 × 106/kg of recipient body weight.

GVHD Prophylaxis and Supportive Care

GVHD prophylaxis initially consisted of cyclosporine-A (CsA) and Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) as previously described (33). GVHD prophylaxis was changed to tacrolimus, sirolimus, and mini-methotrexate at 5 mg/m2 for three doses (tac/siro/mmtx) (34) after 2 of the first 8 patients on protocol experienced severe grade III-IV acute GVHD. Patients were managed clinically according to MSKCC standard guidelines including antimicrobial prophylaxis. Monitoring of CMV reactivation in peripheral blood initially by CMV pp65 antigenemia assay, and later by CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (beginning in November 2011), was performed regularly through day +100 when either the patient or donor was CMV seropositive. Pre-emptive therapy was instituted in patients with documented CMV viremia per institutional standard.

Assessment of efficacy

To assess efficacy as measured by OS and EFS disease restaging per previously aforementioned methods was performed per protocol at day +100, 6 months, 12 months, 18 months, 24 months and yearly thereafter. Cause of death was attributed to B-NHL in cases of POD following allo-SCT (35).

Assessment of safety

Adverse events attributable to the preparative regimen and the allo-SCT such as graft failure/engraftment, GVHD, and opportunistic infections were monitored prospectively. Nonhematologic toxicity within the first 30 days was graded according to common terminology criteria for adverse events (CTCAE) v4.0. Delayed-onset neutropenia (DON) following rituximab therapy was retrospectively collected and analyzed. Neutrophil engraftment was defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) >500/μL on 3 consecutive measurements. Platelet recovery was defined as 3 consecutive measurements of >20,000/μL unsupported by transfusion. Donor/host chimerism was routinely performed at 1, 3 and 6 months from bone marrow and peripheral blood cell subsets for the first year post transplantation using short-tandem repeat (STR) amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the presence of fluorescently-labeled primers (Promega Kit). Mixed chimerism was defined as <90% donor in bone marrow or peripheral blood. aGVHD was graded based upon IBMTR criteria (36), wherein grade A=I, B=II, C=III and D=IV in this manuscript henceforth. cGVHD was based upon NIH criteria (37). TRM was all cases of death without POD. Attribution to TRM was assessed by previously published criteria (35). Utilization of total-parenteral nutrition (TPN) and patient controlled analgesia (PCA) were used as surrogates to estimate mucositis severity.

Statistical analysis

This study was designed as two single-arm phase II trials to explore the efficacy of the drug regimen and allo-SCT for patients receiving related or unrelated grafts. Both were designed to differentiate between an unpromising 1-year EFS of 50%, based upon historic controls, and a promising EFS of 72%. With a type 1 error of 10% and a power of 89%, the target accrual was 30 patients in each cohort for a total sample size of 60. If at least 19 out of the 30 patients remain alive and event-free at 1-year, the treatment regimen would be considered promising for further investigation. This manuscript presents the results as of February 2013. EFS and OS at 1 year and 2 years were estimated using Kaplan-Meier (KM) method. The log-rank test was used to compare EFS or OS between different groups. Other efficacy and safety endpoints were evaluated using competing risk analysis. Death was a competing risk for POD, death due to non-transplant related causes was a competing risk for TRM, and death or progression was a competing risk for aGVHD and cGVHD. Gray's test was used to compare the outcome with competing risks between different groups (38).

Results

Fifty-one consecutive patients transplanted on this clinical trial from March 2007 to September 2012 were included in this analysis. All patients had been previously exposed to rituximab. The median time from diagnosis to allo-SCT was 55 months (range 4-234 months). Of the 10 patients with DLBCL, 5 of them were transformed from previous indolent B-NHL (1 CLL, 2 FL, 1 Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia (WM) and 1 marginal zone lymphoma). Notably, the median HCT-CI was 1. Full patient demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics: 51 patients.

| Median Age | 54 years (range 33-67) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Median Time from Diagnosis to Allo-SCT | 55 months (range 4-234) |

|

| |

| Histology | |

| NHL | 30 pts (59%) |

| DLBCL | 10 pts |

| FL | 14 pts |

| MCL | 4 pts |

| Other | 2 pts |

| CLL/SLL | 21 pts (41%) |

|

| |

| WHO Histologic Subtypes | |

| Indolent | 41 pts (80%) |

| Aggressive | 10 pts (20%) |

|

| |

| HCT-Cl | 1 (median) |

| 0-5 (range) | |

|

| |

| Prior Therapies | 2 (range 1-5) |

|

| |

| Prior Auto Transplant | 9 pts (18%) |

|

| |

| Disease Status at BMT | |

| CR | 22 pts (43%) |

| PR | 17 pts (33%) |

| SD | 11 pts (22%) |

| PD | 1 pt (2%) |

|

| |

| Graft | |

| Related | 18 pts (35%) |

| Unrelated | 33 pts (65%) |

| MUD | 28 pts |

| MMUD | 5 pts |

|

| |

| GVHD Prophylaxis | |

| CSA/MMF | 8 |

| Tacro/Siro/MTX | 43 |

Allo-SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CR, complete remission; CSA, cyclosporine-A; DLBCL, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; FL, follicular lymphoma; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation comorbidity index; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MMUD, mismatched unrelated donor; MTX, methotrexate; MUD, matched unrelated donor; PD, progression of disease; PR, partial remission; SD, stable disease; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma, siro: sirolimus; WHO, world health organization

Forty-five of the 51 patients completed all 4 post-allo SCT doses of rituximab. The treating physicians' rationale for not completing 4 doses in the 6 patients included: cytopenias (2), early severe GVHD (1), early death (1), poor performance status (1) and a suspicious brain lesion (1).

Efficacy

EFS and OS

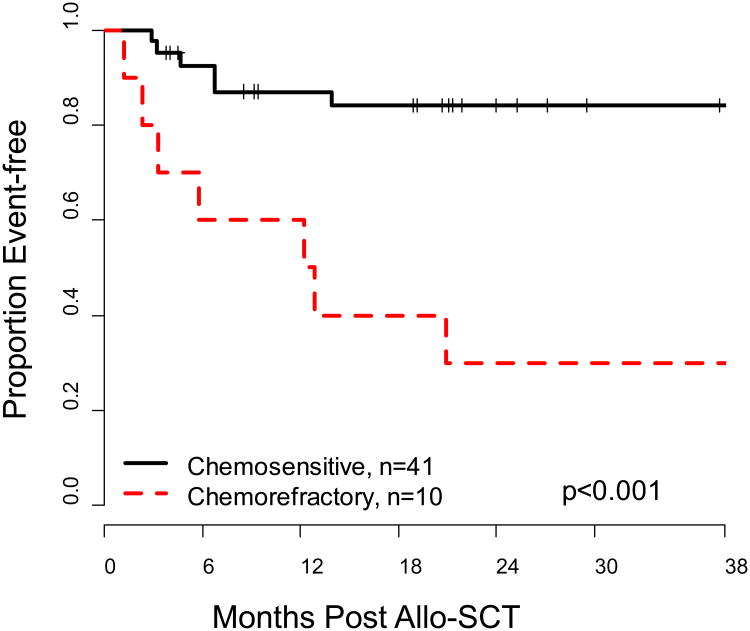

With a median followup of 38 months (range: 4-69 months) the overall one-year EFS of 82% (95% CI: 71-93%). In the unrelated arm, the primary end-point was successfully met with a 77% EFS at one-year (95% CI: 64– 94%). With 18 patients in the related arm, the current EFS is 89% (95%CI: 76 – 100%). The 1-year OS of the entire group was 90% (95%CI: 81-98%). The 2-year OS and EFS were 78% (95% CI: 66-90%) and 72% (95% CI: 59-85%) respectively (Figure 1). Of the pre-allo-SCT factors analyzed including: B-NHL histology, donor source, number of prior therapies, previous ASCT and HCT-CI, only chemosensitivity demonstrated significant prognostic impact. EFS of chemosensitive patients was 84% (95% CI: 72% - 96%) at 2 years compared to 30% (95% CI: 2- 58%) in chemorefractory patients (p<0.001) (Figure 2); which translated into an OS benefit in chemosensitive patients of 86% (95%CI: 74 - 97%) at 2 years compared to chemorefractory patients of 50% (95%CI: 19-81%) (p=0.009).

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Overall (OS) and Event-free Survival (EFS), n=51.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Event-free Survival (EFS) according to Chemosensitivity.

POD, TRM, and Donor Lymphocyte Infusions (DLI)

Of the 13 events: 7 were POD and 6 were TRM. Three patients remain alive following POD. The cumulative incidence of TRM at 1-year was 8% (95%CI: 0-16%), and at 2 years was 13% (95% CI: 3-23%). The cumulative incidence of POD at 1-year was 8% (95%CI: 0-16%), and at 2 years 13% (95% CI: 3-23%) (Figure 3). Five of the 6 transplant related deaths were attributable to GVHD. Two of the first 8 patients expired secondary to grade III and IV aGVHD while on CSA/MMF GVHD prophylaxis, at which time prophylaxis was changed to tac/siro/mmtx. Two patients received DLI within 2 years post transplant. One patient received a DLI for treatment of CMV viremia and subsequently died of complications of GVHD on day +424. Another patient received DLI for POD and subsequently died of B-NHL on day +254.

Figure 3.

(a) Cumulative-incidence of Treatment Related Mortality (TRM)

(b) Cumulative-incidence of Progression of Disease (POD)

Safety

Engraftment and chimerism

The median total nucleated cell-dose (TNC) and CD34+ cell dose were 13.2 × 108/kg (range 1.9-35.0) and 9.9 × 106/kg (range 1.1-31.7) respectively. All patients engrafted neutrophils at a median time of 15 days (range 10-25) post-allo-SCT. Median time to platelet engraftment was 12 days (range 6-40). Full donor chimerism (defined as ≥ 90% donor) was achieved in 80% and 92% of evaluable patients at 1 month and 3 months post-allo-SCT, respectively. Three patients had a mixed marrow chimerism of 75% (CLL, eventual TRM secondary to GVHD at day +382), 65% (t-WM/DLBCL POD with WM in bone marrow day +98), and 60% (CLL POD in bone marrow at day +99) at 3 months post-allo-SCT. T-cell chimerism in peripheral blood was 89%, 91% and 95% at 3, 6 and 12 months respectively.

GVHD

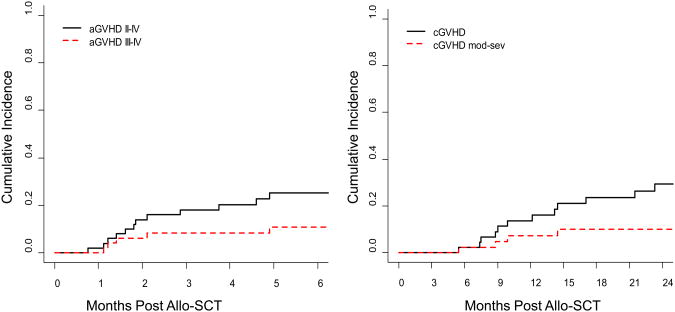

The cumulative incidence of moderate to severe grade II-IV aGVHD at 3 and 6 months post-allo SCT was 18% (95% CI: 7-29%) and 25% (95% CI: 13-38%) respectively, while the cumulative incidence of severe grade III-IV aGVHD was 8% (95% CI: 0-16%) and 11% (95% CI: 2-20%) at 3 and 6 months post-allo-SCT (Figure 4a). There was no difference in incidence, or severity, of aGVHD between related and unrelated donors. The cumulative incidence of cGVHD at 1-year and 2-years post-allo-SCT was 14% (95% CI: 3-24%) and 29% (95% CI: 15-44%), while the cumulative incidence of moderate-severe cGVHD was 7% (95%CI: 0-15%) and 10% (95% CI: 1-20%) at 1 and 2 years post-allo-SCT (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

(a) Cumulative-incidence of Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease (aGVHD)

(b) Cumulative-incidence of Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease (cGVHD)

Toxicity

One patient expired secondary to Stevens - Johnson syndrome representing the only grade 5 nonhematologic toxicity within 30 days of allo-SCT on study. Four cases of hyperglycemia (grade 3) and two cases of alanine aminotransferase elevation (grade 3) were the other grade 3-4 non-hematologic toxicities in the first 30 days post-allo-SCT. None of the patients required narcotic infusions for mucositis during their nadir. Twenty percent of patients required TPN for poor caloric intake.

Of the 49 evaluable patients that received at least one dose of post-allo SCT rituximab, 30 patients (61%) experienced 72 episodes of grade III or IV neutropenia at a median of 10 weeks following the first dose of rituximab (range: 1 day-27 weeks). For these 72 episodes, 92 doses of filgrastim and 22 doses of pegylated filgrastim were administered at treating physicians' discretion. Of the 72 neutropenic episodes, 5 (7%) were associated with fever (Table 2). Of the remaining non-complicated neutropenic episodes, all recovered to ≤ grade II after a median of one dose of growth factor (range: 1-8). There were 2 cases of new grade III thrombocytopenia occurring at 7 and 26 weeks post-initiation of rituximab following allo-SCT without other explanation. There were 9 other cases of new grade III-IV thrombocytopenia (range 1-35 weeks post-rituximab) likely contributed by: thrombocytopenic thrombotic purpura (n=2), active bloodstream infection (n=1), cytomegalovirus infection treated with ganciclovir or valganciclovir (n=4), severe (grade III-IV) aGVHD requiring hospitalization or moderate-severe cGVHD (n=7).

Table 2. Characteristics of 5 Cases of Febrile Neutropenia Episodes following ≥ 1 dose of post-allo SCT Rituximab.

| Day Post Allo-SCT | Clinical Setting | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 45 | active CMV viremia and acute grade III gastrointestinal GVHD | recovered |

| 68 | active acute grade IV gastrointestinal GVHD | died of GVHD while neutropenic |

| 139 | acute cholecystitis | recovered |

| 141 | febrile neutropenia without source | recovered |

| 171 | iatrogenic MSSA abscess and bacteremia following a procedure | recovered |

Allo-SCT, allogeneic stem cell transplant; CMV, cytomegalovirus; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; MSSA, methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus

Immune reconstitution and Viral Opportunistic Infections

The median CD4+ count increased incrementally from 253/μL (inter-quartile range 160-343/μL) at 3 months, to 312/μL at 6 months (inter-quartile range 174-457/μL) and 333/μL at 1-year (inter-quartile 18-1317/μL).

Twenty five percent of patients at risk for CMV infection reactivated and were treated preemptively. Four of the 6 patients who required treatment had been transplanted from unrelated donors. None of the patients developed CMV end-organ disease. There was no Epstein-Barr viral reactivation.

Discussion

Herein we report results of a phase II study utilizing NMA conditioning of cyclophosphamide, fludarabine and low-dose TBI incorporating peri-allo-SCT rituximab in patients with B-NHL with a durable, 2-year EFS of 72% and OS of 78%. This is the first report of peri-allo-SCT rituximab in patients of multiple B-NHL histologies conditioned with a TBI containing NMA regimen receiving allografts from predominately unrelated donors. While the early experience with myeloablative allo-SCT generally yielded poor results secondary to prohibitively high TRM (11, 12); the widespread implementation of RIC has abrogated the risk of TRM often to <25% (13-21), translating into improved outcomes of patients with lymphoma (39). In the setting of RIC, disease-control has largely been attributed to allogeneic graft-versus-lymphoma (GVL) effects (13, 14). These results of our prospective study compare favorably to other reported RIC allo-SCT studies for B-NHL with <10% TRM and POD both at one-year post-alloSCT. Reasons for these encouraging results are likely multifactorial including: incorporation of monoclonal antibody therapy with rituximab, B-NHL disease control with TBI and potentially B-NHL active and effective GVHD prophylaxis with the addition of sirolimus.

Our data corroborates other studies (17, 20, 21, 40-42) in defining chemosensitivity as a significant prognostic factor. We observed a significantly higher 2-year EFS of 84% in chemosensitive patients compared to 30% with SD prior to allo-SCT. While the majority of the events in our chemorefractory patients were due to POD, other groups have reported an independent impact of chemosensitivity on TRM (16, 40, 43). The relatively low HCT-CI (median 1) and the limited number of previous therapies (median 2) in our cohort may have contributed to lower TRM. This observation suggests the potentially cumulative organ toxicity and immune suppression with increasing lines of therapy and/or deleterious physiologic effects of active lymphoma. Given these findings, the negative prognostic impact of chemotherapy-resistance must prompt careful consideration about additional chemotherapy regimens prior to RIC/NMA allo-SCT, especially considering the burgeoning development of highly active, and relatively non-toxic, targeted pathway inhibitors (44, 45).

The incorporation of novel, and relatively safe, anti-B-NHL activity with rituximab may afford enhanced disease-control prior to the development of GVL effects, presumed to take months following NMA allo-SCT. This intervention is not without consequence as 61% of the patients experienced grade III-IV neutropenia, mostly DON, at a median of 10 weeks post-initiation of post-allo rituximab. DON was previously reported in >50% of patients receiving rituximab post-HDT/ASCT (46); and has been described in the non-transplantation setting (47), also at a median of 10 weeks post-rituximab administration as we have reported herein. In our series, this typically was without consequence as 7% of the episodes were associated with fever, with identifiable and concurrent infection with: CMV, acute cholecystitis and abscess/bacteremia in three of the 5 cases along with severe acute GVHD complicating 2 of the 5 cases.

The strategy of peri-NMA allo-SCT was first reported by the group at MDACC in chemosensitive patients with multiply relapsed and refractory FL; wherein long-term follow-up has demonstrated extremely favorable and durable PFS in predominately HLA-matched sibling allo-SCT (19). These results are similar to our cohort of chemosensitive patients, uniquely across all histologies. Outcomes from these studies incorporating peri-NMA allo-SCT transplant anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies appear to compare favorably to those that do not. For example, in a study with a similar fludarabine and cyclophosphamide conditioning backbone, >30% of chemosensitive patients with indolent lymphoma histologies relapsed after RIC allo-SCT (48). In our study, the addition of TBI at 200 cGy not only provides additional immune suppression with very low incidence of mixed-chimerism for a NMA regimen, but may actually contribute to a survival benefit as has been recently reported in a large registry study of RIC allo-SCT for NHL following ASCT failure (49). Lastly, B-cell depletion with rituximab may contribute to reduced TRM and potentially improved survival by its impact on chronic GVHD (50, 51). This would need to be validated in a larger randomized prospective study.

The conditioning regimen was extremely well tolerated on this trial. Despite this, 5 of the 6 transplant-related deaths were attributable to complications of GVHD. This underscores the importance of preventing GVHD in improving OS post-NMA allo-SCT. We report a low incidence of grade II-IV (18%, 25%) and III-IV aGVHD (8%, 11%) at 3 and 6-months post-allo-SCT with the majority of patients having received tac/siro/mmtx GVHD prophylaxis. Our incidence of aGVHD is similar to the original reports for this GVHD prophylaxis regimen in RIC allo-SCT (34, 52). While the addition of sirolimus to calcineurin-inhibitors is not without risk such as dyslipidemia (53) and thrombotic microangiopathy (54); the low incidence of aGVHD (55), particularly severe aGVHD (56), as well as cGVHD (55) make it quite attractive. Moreover, based on the reported contribution of the (mTOR) pathway, which is targeted by sirolimus, to pro-survival signals in several histologic subsets of NHL (57), this immune suppressive regimen may provide added protection from progression of lymphoma (58). We observed a relatively low incidence of cGVHD of 29% at 2 years post-SCT, with the majority being mild (incidence of moderate-severe 10%). The results or our institutional experience with tac/siro/mmtx in conjunction with RIC allo-SCT across all hematologic malignancies will be reported in a forthcoming manuscript. The potential contribution of eATG (59-61) and/or rituximab in the peri-allo-SCT period (50, 51) to a reduction in cGVHD would need to be verified in a prospective randomized trial.

In conclusion, we report favorable EFS in this prospective phase II study incorporating rituximab and low-dose TBI into a NMA allo-SCT for B-NHL, especially in chemosensitive patients. In light of these findings, early referral for NMA allo-SCT should be considered in poor-risk B-NHL patients while chemosensitivity is preserved. The contributions of rituximab, sirolimus, eATG and low-dose TBI to the success of this treatment program would need to be validated in a prospective randomized trial. Potential shortfalls of this phase II study include relatively non-comorbid patients (median HCT-CI of 1) treated at a single, tertiary referral center. Lastly, given ours and other centers success introducing drugs such as rituximab and sirolimus into RIC allo-SCT regimens, future emphasis should be placed on identifying and developing targeted lymphotoxic pharmaceuticals (62) that may provide both anti-B-NHL disease activity and effective GVHD prevention which may continue to improve OS of these patients.

Acknowledgments

C.S. and H.C-M interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. H.C-M. and J.N.B. designed the study. C. S., L.L., J.Z., and S.M.D. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. E.B.P., M-A.P., A.A.J., J.D.G., G.K., I.C., S.G., C.H.M., and A.D.Z wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: C.S., J.N.B., L.L., J.Z., S.M.D., E.B.P., M-A.P., A.A.J., J.D.G., G.K., I.C., S.G., C.H.M., and H.C-M. have nothing to disclose. A.D.Z.: receives research funding from Genentech. Genentech provided rituximab for this study.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fisher RI, LeBlanc M, Press OW, Maloney DG, Unger JM, Miller TP. New treatment options have changed the survival of patients with follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8447–8452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keegan TH, Moy LM, Foran JM, et al. Rituximab use and survival after diffuse large B-cell or follicular lymphoma: a population-based study. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012 doi: 10.3109/10428194.2012.727415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:520–531. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robak T, Lech-Maranda E, Robak P. Rituximab plus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide or other agents in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2010;10:1529–1543. doi: 10.1586/era.10.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with salvage chemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-sensitive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1540–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512073332305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisselbrecht C, Glass B, Mounier N, et al. Salvage Regimens With Autologous Transplantation for Relapsed Large B-Cell Lymphoma in the Rituximab Era. J Clin Oncol. 2010 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geisler CH, Kolstad A, Laurell A, et al. Long-term progression-free survival of mantle cell lymphoma after intensive front-line immunochemotherapy with in vivo-purged stem cell rescue: a nonrandomized phase 2 multicenter study by the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2008;112:2687–2693. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaffel R, Hedvat CV, Teruya-Feldstein J, et al. Prognostic impact of proliferative index determined by quantitative image analysis and the International Prognostic Index in patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:133–139. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schouten HC, Qian W, Kvaloy S, et al. High-dose therapy improves progression-free survival and survival in relapsed follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: results from the randomized European CUP trial. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3918–3927. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lenz G, Dreyling M, Schiegnitz E, et al. Myeloablative radiochemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in first remission prolongs progression-free survival in follicular lymphoma: results of a prospective, randomized trial of the German Low-Grade Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 2004;104:2667–2674. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Besien K, Sobocinski KA, Rowlings PA, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for low-grade lymphoma. Blood. 1998;92:1832–1836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacher U, Klyuchnikov E, Le-Rademacher J, et al. Conditioning regimens for allotransplants for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: myeloablative or reduced intensity? Blood. 2012;120:4256–4262. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-436725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khouri IF, Keating M, Korbling M, et al. Transplant-lite: induction of graft-versus-malignancy using fludarabine-based nonablative chemotherapy and allogeneic blood progenitor-cell transplantation as treatment for lymphoid malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2817–2824. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.8.2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Besien KW, de Lima M, Giralt SA, et al. Management of lymphoma recurrence after allogeneic transplantation: the relevance of graft-versus-lymphoma effect. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1997;19:977–982. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Kampen RJ, Canals C, Schouten HC, et al. Allogeneic stem-cell transplantation as salvage therapy for patients with diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma relapsing after an autologous stem-cell transplantation: an analysis of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Registry. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1342–1348. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezvani AR, Norasetthada L, Gooley T, et al. Non-myeloablative allogeneic haematopoietic cell transplantation for relapsed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre experience. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rezvani AR, Storer B, Maris M, et al. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in relapsed, refractory, and transformed indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:211–217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.11.5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson KJ, Morris EC, Milligan D, et al. T-cell-depleted reduced-intensity transplantation followed by donor leukocyte infusions to promote graft-versus-lymphoma activity results in excellent long-term survival in patients with multiply relapsed follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3695–3700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khouri IF, McLaughlin P, Saliba RM, et al. Eight-year experience with allogeneic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular lymphoma after nonmyeloablative conditioning with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab. Blood. 2008;111:5530–5536. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dreger P, Dohner H, Ritgen M, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation provides durable disease control in poor-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia: long-term clinical and MRD results of the German CLL Study Group CLL3X trial. Blood. 2010;116:2438–2447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corradini P, Dodero A, Farina L, et al. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation following reduced-intensity conditioning can induce durable clinical and molecular remissions in relapsed lymphomas: pre-transplant disease status and histotype heavily influence outcome. Leukemia. 2007;21:2316–2323. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morris E, Thomson K, Craddock C, et al. Outcomes after alemtuzumab-containing reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation regimen for relapsed and refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2004;104:3865–3871. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cook G, Smith GM, Kirkland K, et al. Outcome following Reduced-Intensity Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation (RIC AlloSCT) for relapsed and refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL): a study of the British Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:1419–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. NCI Sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorror ML, Maris MB, Storb R, et al. Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT)-specific comorbidity index: a new tool for risk assessment before allogeneic HCT. Blood. 2005;106:2912–2919. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jazirehi AR, Huerta-Yepez S, Cheng G, Bonavida B. Rituximab (chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) inhibits the constitutive nuclear factor-{kappa}B signaling pathway in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma B-cell lines: role in sensitization to chemotherapeutic drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:264–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bonavida B. Rituximab-induced inhibition of antiapoptotic cell survival pathways: implications in chemo/immunoresistance, rituximab unresponsiveness, prognostic and novel therapeutic interventions. Oncogene. 2007;26:3629–3636. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Oers MH, Klasa R, Marcus RE, et al. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial. Blood. 2006;108:3295–3301. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forstpointner R, Unterhalt M, Dreyling M, et al. Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: Results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG) Blood. 2006;108:4003–4008. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peggs KS. Immune reconstitution following stem cell transplantation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1093–1101. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001641260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dall'Ozzo S, Tartas S, Paintaud G, et al. Rituximab-dependent cytotoxicity by natural killer cells: influence of FCGR3A polymorphism on the concentration-effect relationship. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4664–4669. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ponce DM, Sauter C, Devlin S, et al. A Novel Reduced Intensity Conditioning Regimen Induces a High Incidence of Sustained Donor-Derived Neutrophil and Platelet Engraftment after Double-Unit Cord Blood Transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alyea EP, Li S, Kim HT, et al. Sirolimus, tacrolimus, and low-dose methotrexate as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis in related and unrelated donor reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:920–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Copelan E, Casper JT, Carter SL, et al. A scheme for defining cause of death and its application in the T cell depletion trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13:1469–1476. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowlings PA, Przepiorka D, Klein JP, et al. IBMTR Severity Index for grading acute graft-versus-host disease: retrospective comparison with Glucksberg grade. Br J Haematol. 1997;97:855–864. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1997.1112925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, et al. National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:945–956. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gray RJ. A Class of K-Sample Tests for Comparing the Cumulative Incidence of a Competing The Annals of Statistics. 1988;16:1141–1154. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avivi I, Montoto S, Canals C, et al. Matched unrelated donor stem cell transplant in 131 patients with follicular lymphoma: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Br J Haematol. 2009;147:719–728. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vigouroux S, Michallet M, Porcher R, et al. Long-term outcomes after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for low-grade lymphoma: a survey by the French Society of Bone Marrow Graft Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (SFGM-TC) Haematologica. 2007;92:627–634. doi: 10.3324/haematol.10924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomson KJ, Morris EC, Bloor A, et al. Favorable long-term survival after reduced-intensity allogeneic transplantation for multiple-relapse aggressive non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:426–432. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson SP, Goldstone AH, Mackinnon S, et al. Chemoresistant or aggressive lymphoma predicts for a poor outcome following reduced-intensity allogeneic progenitor cell transplantation: an analysis from the Lymphoma Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Bone Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2002;100:4310–4316. doi: 10.1182/blood-2001-11-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pinana JL, Martino R, Gayoso J, et al. Reduced intensity conditioning HLA identical sibling donor allogeneic stem cell transplantation for patients with follicular lymphoma: long-term follow-up from two prospective multicenter trials. Haematologica. 2010;95:1176–1182. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.017608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castillo JJ, Furman M, Winer ES. CAL-101: a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase p110-delta inhibitor for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies. Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2012;21:15–22. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.640318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Advani RH, Buggy JJ, Sharman JP, et al. Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Ibrutinib (PCI-32765) Has Significant Activity in Patients With Relapsed/Refractory B-Cell Malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.7906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horwitz SM, Negrin RS, Blume KG, et al. Rituximab as adjuvant to high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2004;103:777–783. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cattaneo C, Spedini P, Casari S, et al. Delayed-onset peripheral blood cytopenia after rituximab: frequency and risk factor assessment in a consecutive series of 77 treatments. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:1013–1017. doi: 10.1080/10428190500473113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Auer RL, MacDougall F, Oakervee HE, et al. T-cell replete fludarabine/cyclophosphamide reduced intensity allogeneic stem cell transplantation for lymphoid malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2012;157:580–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Freytes CO, Zhang MJ, Carreras J, et al. Outcome of lower-intensity allogeneic transplantation in non-Hodgkin lymphoma after autologous transplantation failure. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18:1255–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.12.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arai S, Sahaf B, Narasimhan B, et al. Prophylactic rituximab after allogeneic transplantation decreases B-cell alloimmunity with low chronic GVHD incidence. Blood. 2012;119:6145–6154. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cutler C, Kim HT, Bindra B, et al. Rituximab prophylaxis prevents corticosteroid-requiring chronic GVHD after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation: results of a phase II trial. Blood. 2013 doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-495895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho VT, Aldridge J, Kim HT, et al. Comparison of Tacrolimus and Sirolimus (Tac/Sir) versus Tacrolimus, Sirolimus, and mini-methotrexate (Tac/Sir/MTX) as acute graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15:844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Griffith ML, Savani BN, Boord JB. Dyslipidemia after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: evaluation and management. Blood. 2010;116:1197–1204. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laskin BL, Goebel J, Davies SM, Jodele S. Small vessels, big trouble in the kidneys and beyond: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Blood. 2011;118:1452–1462. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-321315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pidala J, Kim J, Jim H, et al. A randomized phase II study to evaluate tacrolimus in combination with sirolimus or methotrexate after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2012;97:1882–1889. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.067140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cutler C, L BR, Nakamura R, Johnston L, Choi SW, Porter DL, Hogan WJ, Pasquini MC, MacMillan ML, Wingard JR, Waller EK, Grupp SA, McCarthy PL, Wu J, Hu Z, Carter SL, Horowitz ML, Antin JH. Tacrolimus/Sirolimus Vs. Tacrolimus/Methotrexate for Graft-Vs.-Host Disease Prophylaxis After HLA-Matched, Related Donor Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Results of Blood and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network Trial 0402. Blood. 2012;120 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schatz JH. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: results, biology, and development strategies. Current oncology reports. 2011;13:398–406. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0187-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Armand P, Gannamaneni S, Kim HT, et al. Improved survival in lymphoma patients receiving sirolimus for graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation with reduced-intensity conditioning. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5767–5774. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Socie G, Schmoor C, Bethge WA, et al. Chronic graft-versus-host disease: long-term results from a randomized trial on graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis with or without anti-T-cell globulin ATGFresenius. Blood. 2011;117:6375–6382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-329821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malard F, Cahu X, Clavert A, et al. Fludarabine, antithymocyte globulin, and very low-dose busulfan for reduced-intensity conditioning before allogeneic stem cell transplantation in patients with lymphoid malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2011;17:1698–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Soiffer RJ, Lerademacher J, Ho V, et al. Impact of immune modulation with anti-T-cell antibodies on the outcome of reduced-intensity allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2011;117:6963–6970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koreth J, Stevenson KE, Kim HT, et al. Bortezomib-Based Graft-Versus-Host Disease Prophylaxis in HLA-Mismatched Unrelated Donor Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3202–3208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]