Abstract

Objectives

Robotic sacrocolpopexy has been rapidly incorporated into surgical practice without comprehensive and systematically published outcome data. The aim of this study was to systematically review the current published peer-reviewed literature on robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with greater than six-month anatomic outcome data.

Methods

Studies were selected after applying predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria to a MEDLINE search. Two independent reviewers blinded to each other’s results abstracted demographic data, perioperative information and postoperative outcomes. The primary outcome assessed was anatomic success rate defined as ≤POP-Q Stage 1. A random effects model was performed for meta-analysis of selected outcomes.

Results

13 studies were selected for the systematic review. Meta-analysis yielded a combined estimated success rate of 98.6% (95%CI 97.0–100%). The combined estimated rate of mesh exposure/erosion was 4.1% (95%CI 1.4–6.9%), and the rate of reoperation for mesh revision was 1.7%. The rates of reoperation for recurrent apical and non-apical prolapse were 0.8% and 2.5% respectively. The most common surgical complication (excluding mesh erosion) was cystotomy (2.8%), followed by wound infection (2.4%).

Conclusions

The outcomes of this analysis indicate that robotic sacrocolpopexy is an effective surgical treatment for apical prolapse with high anatomic cure rate and low rate of complications.

Keywords: sacrocolpopexy, robotics, pelvic organ prolapse, mesh erosion

Introduction

The prevalence of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) is increasing with our aging population. Conservative estimates show that the number of women suffering from prolapse will increase by 46% from 3.3 million to 4.9 million over the next 40 years.1 Currently, more than 220,000 women undergo surgical management for symptomatic prolapse every year;2 and the reoperation rate is estimated at 30%.3 These statistics emphasize the importance of utilizing a highly effective, durable procedure with low morbidity while limiting cost in order to effectively surgically manage symptomatic POP.

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy (ASC), an abdominal approach to apical and anterior vaginal prolapse, is considered to be the gold standard treatment for vaginal vault prolapse. Numerous studies have shown this procedure to have high success rates (78–100%) and long-term durability.3 The procedure is associated with significantly less recurrent prolapse when compared to vaginal reconstruction procedures.4 However, many surgeons continue to perform vaginal prolapse surgery in order to avoid the increased morbidity associated with an abdominal approach, including longer operative and recovery time.5

The laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (LSC) helps to bridge the gap by maintaining surgical efficacy with low rates of operative morbidity. A recent randomized controlled trial comparing abdominal and laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy showed no significant difference in the anatomic outcomes at one year.6 Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy has been associated with less blood loss and decreased hospital stay. Complication rates including mesh erosion are low and appear similar in both procedures.7 Although the laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy is highly effective with low associated morbidity, the procedure has not been universally adopted because it requires advanced laparoscopic skills not easily accessible to the majority of gynecologic surgeons already in practice and is known to have a steep learning curve.

The potential advantages of robotic versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy lie in the “wrist” of the robotic instruments that allows more freedom of motion and the improved optics. These advantages, though unproven, may theoretically translate to easier dissection, improved visualization of the promontory, precise suture placement, and easier knot-tying with a faster learning curve. The surgeon is also less reliant on having a skilled bedside assistant compared to traditional laparoscopy. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy (RSC) has been rapidly incorporated into clinical practice without comprehensive and systematically published outcome data. The aim of this study was to systematically review the current published peer-reviewed literature on robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with greater than six-month anatomic outcome data.

Materials and Methods

Search Strategy

This study was exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University. Systematic review and meta-analysis was performed with adherence to the PRISMA guidelines.8 A PubMed and Ovid MEDLINE search was performed using the terms “robot* AND sacrocolpopexy”, “robot* AND sacral colpopexy”, “robot* AND promontofixation”, “DaVinci AND sacrocolpopexy”, “DaVinci AND sacral colpopexy”, and “DaVinci AND promontofixation”. All of the identified articles were then limited to English language and duplicates were removed. The remaining articles were eligible for abstract review. No additional peer-reviewed articles were included for review after December 2012.

Abstract and full text review

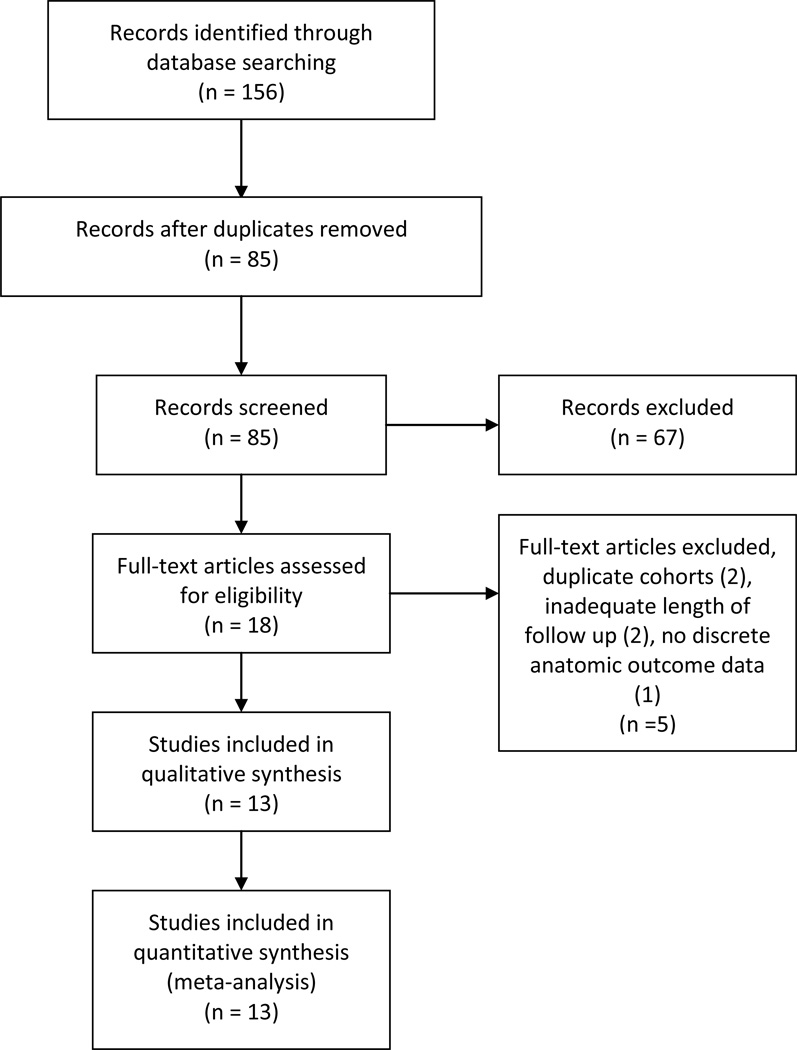

A single investigator reviewed the abstracts. Figure 1 demonstrates the study selection process. Previously determined inclusion criteria were 1) published original research, 2) studies assessing greater than six-month postoperative anatomic outcomes after robotic sacrocolpopexy, and 3) English language articles. Abstracts were eligible for full-text review if they met the inclusion criteria. Abstracts were then excluded if 1) size of study cohort was less than 15 or 2) follow up was less than 6 months. The eligible articles were independently reviewed by the first and last authors who were blinded to each other’s results. Additional articles that met inclusion criteria were identified from the references of the eligible studies and then included for full-text review. Further studies were excluded if a duplicate cohort was present or if upon full-text review they met previous exclusion criteria. In cases of duplicate patient cohorts, the most recent published data was analyzed and the earlier published study was excluded from review. The remaining articles were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis.

Figure 1. Study Selection.

Flowsheet of study selection process adapted from PRISMA guidelines.8

The two independent reviewers abstracted methodological details of each study as well as demographic, perioperative, and postoperative data. A standardized data sheet, constructed from Microsoft Excel, was used consisting of parameters to be abstracted from all studies. The risk of bias was assessed for each study. Abstracted demographic data included age, body mass index, parity, and preoperative prolapse stage/grade. Perioperative data included estimated blood loss, operative time, concomitant procedures, intraoperative complications, conversion rates, and length of hospital stay. Postoperative outcomes recorded included length of follow-up, postoperative prolapse stage/grade, postoperative complications, and reoperation rates. Subjective outcomes were also recorded including use of validated pelvic floor questionnaires, patient satisfaction scales, and postoperative dyspareunia. Strengths and limitations including potential bias and loss to follow up were also documented for each included study. The data was compiled from the selected studies and subsequently analyzed.

Our primary outcome was anatomic cure rate defined as apical prolapse less than or equal to POP-Q stage 1. We based this definition of anatomic cure on the most commonly cited definition of “cure” within the abstracted studies. When POP-Q stage was not explicitly stated, the stage was extrapolated from the measurement data.

Assessment of risk of bias

The quality of the selected articles was assessed using a risk of bias approach. The Cochrane risk-of-bias tool was used to assess randomized controlled trials with the following possible measures: low risk, high risk, or unclear risk.9 The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale was used to assess the risk of bias of the individual non-randomized observational studies. This scale was developed to assess the quality of non-randomized trials based on subject selection, comparability of the study cohort, and ascertainment of the outcome measure. The scale uses a star scoring method where one star can be awarded in each category with the exception of comparability which can receive two stars. In the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale the maximum score for comparative observational cohort studies is 9 stars. The maximum score for non-comparative observational cohort studies is 6 stars.10

Statistical methods

Weighted mean averages and weighted standard deviations were calculated for those outcomes reported as means in the selected studies including age, body mass index, length of follow up, operative time, and length of hospital stay. Simple averages were calculated for secondary outcomes reported as counts or rates, including sample size, loss to follow-up, concomitant procedures, conversion rates, and complication rates.

Meta-analysis was performed on selected objective data including the primary outcome of anatomic cure rate, rate of cystotomy, vaginal mesh erosion or exposure, and reoperation rates using a random effects model. Total reoperation rate was defined as any surgical intervention that could be causally linked to the original procedure. Rate of reoperation for prolapse included any surgical intervention to treat prolapse after the initial RSC, differentiating between apical and non-apical prolapse.

To estimate the overall cure rate, a logistic-normal (nonlinear mixed) model was fit to the individual-specific outcome data, allowing a random effect across studies. The SAS NLMIXED procedure11 was used to fit the model via maximum likelihood. Upon obtaining the estimated logit-scale intercept and its corresponding standard error, the delta method was used to approximate the standard error of the corresponding estimated overall cure rate. This random effects model-based approach was applied directly to obtain the estimate, standard error, and approximate 95% confidence intervals with regard to the anatomic cure rate, cystotomy rate, and mesh erosion rate. However, the estimated across-study variance component was 0 when fitting this model to the remaining two outcomes (total reoperation rate and prolapse reoperation rate). Therefore, the random study effect was dropped from the model and the model was re-fit to the data. The resulting estimated rates, standard errors, and confidence intervals for these last two outcomes are equivalent to simple averages, assuming independence of the individual patient outcomes within and across studies.

Results

A total of 85 articles were identified using the search criteria after limiting to English language articles and removing duplicate studies. After abstract review, 18 articles were eligible for full-text review after inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied. Two early studies12–13 were excluded after the patient cohorts were noted to be identical to later published data14–15. Two studies16–17 were excluded after full-text review revealed mean follow up of less than 6 months. Kramer et al.18 was excluded because there was not discrete postoperative anatomic data reported in the article. After complete review, 13 studies were included in the systematic review with publication dates ranging from May 2008 to November 2012.

Details of selected studies are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The selected studies included one randomized controlled trial, five prospective cohort studies, and seven retrospective cohort studies. Within the 13 selected studies, a total of 577 patients underwent robotic assisted sacrocolpopexy. The weighted mean average patient age was 61.1±2.3 years. All of the women included in the studies had greater than or equal to POP-Q stage 2 prolapse. Of the 9 studies that reported mean follow-up, the weighted average was 26.9±17.3 months. Four studies reported follow-up using other methods. The average percentage of patients lost to follow up at 6-month time period among the 12 reporting studies was 16.6% (range 0–63.5%).

Table 1.

Study design and demographic data

| Study | Design | Brief Description | Robotic N |

N of pts w/ 6 month data |

Lost to f/u (no anatomic data >6mos) |

Mean f/u (months) |

Mean age (years) |

Mean BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benson 2010 | retrospective | Non-comparative | 33 (21 RALS, 12 SRALS) | 33 | 0 | 38.4 RALS, 20.7 SRALS | 65 RALS / 59 SRALS | NR |

| Chan 2011 | retrospective | comparative LSC vs RSC | 16 | 15 | 1 | 16 | 67.4 (SD 9.3) | NR |

| Geller 2011 | prospective | Non-comparative | 25 | 15 | 10 | 14.8 (SD 3.8) | 60.1 (SD 10.1) | 29.5 (SD 5.7) |

| Geller 2012 | retrospective | comparative ASC vs RSC | 23 | 23 | 0 | 44.2 (SD 6.4) | 61.7 (SD 10.7) | 25.4 (SD 3.9) |

| Matthews 2012 | prospective | Non-comparative | 85 | 31 | 54 | 6 month f/u=31; 6wk f/u=83 | 59 (SD 8.85) | 27.6 (SD 4.42) |

| Moreno-Sierra 2011 | prospective | Non-comparative | 31 | 31 | NR | 24.5 (range 16–33) | 65.2 (range 50–81) | NR |

| Mourik 2012 | prospective | Non-comparative | 50 | 42 | 8 | 16b (range 8–29) | 57.7 (range 36–77) | 25.8 (range 20.3–35.2) |

| Paraiso 2011 | RCT | comparative LSC vs RSC | 35 | 28 | 7 | 26/39 w/ 12 month data | 61.0 (SD 9.0) | 29 (SD 5) |

| Seror 2011 | prospective | comparative LSC vs RSC | 20 | 20 | 0 | 15 (range 10–36) | 60 (SD 11.5) | 24.7 (SD 3.5) |

| Shariati 2008 | retrospective | Non-comparative | 77 | 62 | 15 | 7 (range 0–12) | 61.3 (SD 9.9) | 26.1 (SD 3.9) |

| Shimko 2011 | retrospective | Non-comparative | 40 | 40 | 0 | 59 (range 36–84) | 67 (range 43–83) | NR |

| Shveiky 2010 | retrospective | comparative VSC with mesh vs RSC | 17 | 17 | 0 | 12.3b (range 3.2–21.2) | 55.8b (SE 9.8) | 25.4b (SE 2.6) |

| Siddiqui 2012 | retrospective | comparative ASC vs RSC | 125 | 70 | 55 | 18.3 (SD 6.7) | 59.5 (SD 9.8) | 26.6 (SD 5.7) |

| Pooled estimates | 577 | 427 | 150 | 26.9±17.3a | 61.1±2.3a | 26.8±1.7a |

– Weighted mean averages and weighted standard deviation,

- median

AR anterior repair, NR not recorded, PR posterior repair, RAH robotic total hysterectomy, RALS Robot assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, RSCH Robotic Supracervical Hysterectomy, SD standard deviation, SE standard error, SSF sacrospinous ligament fixation, SRALS Supracervical Robot assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, TVM total vaginal mesh, VSC vaginal colpopexy

Table 2.

Perioperative Data and Postoperative Outcomes

| Study | EBL (ml) |

Total Op time (min) |

Concomitant hysterectomy |

Other concomitant procedures |

Anti- incontinence procedure rate |

Conversion rate |

LOS (days) |

Complications |

Cystotomy rate |

Mesh erosion rate |

Anatomic cure rated |

Reoperation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Benson 2010 |

RALS 50 (range 25– 150); SRALS 108 (range 50–225) |

RALS 194; SRALS 284 |

RSCH (12) | None | 0 (0%) | NR | 1.06 | SBO (2) fever (1) | 0/33 (0%) | 0/33 (0%) | 32/33 (97.0%) | SBO (2) SSF (1) |

|

Chan 2011s |

131 (SD 79.3) |

230 (SD 42) | None | paravaginal repair (15) TVT (2) Burch (1) |

3 (18.8%) | NR | 7.5 | cystotomy (2) ureteral injury (1) port site hernia (1) DVT (1) postop fever (1) |

2/16 (12.5%) | NR | 14/15 (93.3%) | port site hernia (1) TVM (1) |

|

Geller 2011 |

NR | console time RSC 133 min (SD 31); mean console time for hyst 75min (SD 22) |

RAH (21) | midurethral sling (13) |

13 (52%) | 0/25 (0%) | NR | mesh erosion (2) | 0/25 (0%) | 2/15 (13.3%) |

15/15 (100%) | PR (1) AR&PR (1) |

|

Geller 2012 |

151 (SD 111) | NR | RAH (1) RSCH (10) |

midurethral sling (14) AR (2) PR (1) |

14 (60.8%) | NR | NR | mesh erosion (2) | 0/23 (0%) | 2/23 (8.7%) | 23/23 (100%) | PR (1) |

|

Matthews 2012 |

49.9 (SD 48) | 194.8b (SD 54) | RSCH (37) | midurethral sling (39) PR (11) AR (4) perineoplasty (22) |

39 (45.9%) | 1/85 (1.2%) | 1.6 | cystotomy (4) proctotomy (2) UTI (8) PNA (1) arrhythmia (1) mesh erosion (2) |

4/85 (4.7%) | 2/31 (6.5%) | 31/31 (100%) | mesh excision (1) non- apical POP(1) |

|

Moreno- Sierra 2011 |

NR | 186 (range 150– 230) |

None | TOT (30) | 30 (96.8%) | 1/31 (3.2%) | 4.6 | cystotomy (1) vaginal injury (1) MI (1) wound infection (1) ileus (1) syncopal crisis w/ repeat surgery to release tension on posterior mesh (1) |

1/31 (3.2%) | 0/31 (0%) | 31/31 (100%) | 1 reoperation (RAL release and resuturing of posterior mesh) |

|

Mourik 2012 |

<50ml | 223b (range 103– 340) - excluded cases with concomitant procedures |

RAH (1) | BTL (7) adnexectomy (5) |

0 (0%) | 2/50 (4.0%) | 3b | ileus (1) neuropathy (1) | 0/50 (0%) | 0/42 (0%) | 42/42 (100%) | 1 vaginal sacrospinous colpopexy/trachelectomy |

|

Paraiso 2011 |

NR | 265b (SE 51) | None | anti-incontinence procedure (25) PR (10) |

25 (71.4%) | 3/35 (8.6%) | 1.5 | cystotomy (2) enterotomy (1) corneal abrasion (1) SBO (2) abscess (1) wound infection (2) UTI (5) mesh erosion (2) |

2/35 (5.7%) | 2/28 (7.1%) | 23/26 (88.4%) | NR |

|

Seror 2011 |

55 (SD 30) | 217 (SD 40.9) | None | TVT (3) TOT (3) | 6 (17.1) | 1/20 (5%) | 5.1 | UTI (1) | 0/20 (0%) | 0/20 (0%) | 19/20 (95.0%) | NR |

|

Shariati 2008 |

NR | 273 (range 205– 395) |

TVH (3) | TVT (33) PR (65) |

33 (42.9%) | 1/77 (1.3%) | 2b | cystotomy (4) presacral hemorrhage (1) blood transfusion (1) enterotomy (1) ileus (5) C. diff (2) mesh erosion (3) |

4/77 (5.2%) | 7/62 (11.2%) |

61/62 (98.4%) | mesh excision (3) |

|

Shimko 2011 |

NR | 186 (range 129– 300) |

None | autologous pubovaginal sling (1) synthetic pubovaginal sling (22) TOT (4) |

27 (67.5%) | 3/40 (7.5%) | 1.2 | port site hernia (1) wound infection (2) mesh erosion (2) |

0/40 (0%) | 2/40 (5.0%) | 40/40 (100%) | PR (2) port site hernia (1) mesh excision (2) |

|

Shveiky 2010 |

70.6b (SE 31.0) |

359.7 (SD 61.0) | RSCH (9) | midurethral sling (5) PR (10) |

5 (29.4%) | 0/17 (0%) | 1.3 | cystotomy (1) UTI (2) nerve compression (1) |

1/17 (5.9%) | 0/17 (0%) | 16/17 (94.1%) | NR |

|

Siddiqui 2012 |

90.0 (SD 89.3) |

NR | RSCH (59) RAH (2) |

midurethral sling (52) PR (10) |

52 (41.6%) | NR | NR | cystotomy (2) wound infection (6) fever (6) transfusion (1) ileus (7) PNA (2) DVT (1) mesh erosion (3) |

2/125 (1.6%) | 3/70 (4.3%) | 70/70 (100%) | PR (3) port site nerve entrapment (1) |

|

Pooled estimates |

82.5±21a | 230.5±19.6a |

247/577 (42.8%) |

12/380 (3.2%) |

2.4±6.4a | 2.6%c | 4.1%c | 98.6%c |

– Weighted mean averages and weighted standard deviation,

– median,

– estimates based on random effects model (see Table 5),

– Apical prolapse </= POP-Q Stage 1

AR anterior repair, NR not recorded, PR posterior repair, RAH robotic total hysterectomy, RALS Robot assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, RSCH Robotic Supracervical Hysterectomy, SD standard deviation, SE standard error, SSF sacrospinous ligament fixation, SRALS Supracervical Robot assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy, TVM total vaginal mesh, VSC vaginal colpopexy

Estimated blood loss was reported by six of the studies with a weighted average of 82.5±21 ml. Total operative time, defined as time from incision to skin closure, was reported by 9 studies. Weighted average total operative time was 235±18.8 minutes. Geller et al19 did not report total operative time but reported mean console time for the sacrocolpopexy portion as 133±31 minutes separate from the mean console time for the hysterectomy portion at 75±22 minutes. Mourik et al20 reported a median total operative time of 223 minutes (range 103–340) but excluded those patients who underwent concomitant procedures.

The majority of patients underwent concomitant procedures. Midurethral slings were the most commonly performed at a rate of 42.8%, followed by hysterectomy (26.7%) and posterior repair (18.5%). The majority of hysterectomies performed at the time of robotic sacrocolpopexy were supracervical (127/152) (83.6%). Rate of conversion to laparotomy was reported in 9 of 13 studies. The mean conversion rate was low at 3.2% (0–8.6%). The most commonly cited reason for conversion was pelvic adhesions in 5 cases. Other reasons for conversion were equipment malfunction (2) and cystotomy repair (1). The weighted mean average length of hospital stay was 2.4±6.4 days for the eight reporting studies. Two articles reported median length of stay (Table 2).20–21

Overall, complications were rare. The most common surgical complication (excluding mesh exposure/erosion) was cystotomy (2.6%), followed by wound infection (2.4%), small bowel obstruction (0.7%), enterotomy (0.3%), and port site hernia (0.3%). There were no deaths attributable to the procedure reported in any of the studies.

The one randomized controlled trial included from Paraiso et al22 was analyzed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. This study demonstrated a low risk of bias except in the area of completeness of outcome data given the loss to follow up. Based on our modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale10, the overall quality of the observational studies was good (Table 3). Of the 12 observational studies, 5 studies were comparative in nature with a mean score of 8.8 out of 9 stars (range 8–9). Seven studies were non-comparative cohort studies with a mean score of 5.7 out of 6 stars (range 5–6).

Table 3.

Risk of bias assessment*

| Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for non-randomized observational studies10 | |||||||||

| Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Totals | ||||||

| Study | Representativeness of tde exposed cohort |

Selection of tde non- exposed cohort |

Ascertainment of exposure |

Outcome not present at beginning of study |

Comparability of cohorts |

Assessment of outcome |

Was follow up long enough? |

Adequacy of follow up |

|

| Benson et al 2010 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | 6/6 |

| Chan et al 2011 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Geller et al 2011 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | - | 5/6 |

| Geller et al 2012 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Matthews et al 2012 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | - | 5/6 |

| Moreno-Sierra et al 2011 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | 6/6 |

| Mourik et al 2012 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | 6/6 |

| Seror et al 2011 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Shariati et al 2008 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | 6/6 |

| Shimko et al 2011 | * | N/A | * | * | N/A | * | * | * | 6/6 |

| Shveiky et al 2010 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | * | 9/9 |

| Siddiqui et al 2012 | * | * | * | * | ** | * | * | - | 8/9 |

| Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized studies9 | |||||||||

| Study | Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment |

Blinding of participants and personnel |

Blinding of outcome assessment |

Incomplete Outcome Data |

Selective Reporting |

Other sources of bias | ||

| Paraiso et al 2011 | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | ||

In the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale the maximum score for comparative observational cohort studies is 9 stars. The maximum score for non-comparative observational cohort studies is 6 stars.

Long-term outcomes

The primary outcome assessed was apical anatomic success rate defined as POP-Q Stage </= 1. This was reported in all 13 of the selected studies and the combined estimate yielded an overall apical anatomic cure rate of 98.6% (95%CI 97.0–100%). Table 4 lists the estimates for cure rate, cystotomy, mesh exposure/erosion, total reoperation rate and prolapse reoperation rate. Of the studies that commented on location of exposure/erosion, posterior vagina (6) was most common, followed by the apex (3) and anterior vagina (2). For 9 of the 20 mesh exposures/erosions, no location was specified. Paraiso et al22 reported that one of the 2 mesh erosions was from a suburethral sling.

Table 4.

Overall Estimated Proportions After Combining Studies

| Overall cure rate a |

Cystotomy a | Mesh erosion a |

Total reoperation rate b |

Prolapse reoperation rate b |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | 0.986 (0.008) | 0.026 (0.009) | 0.041 (0.014) | 0.066 (0.013) | 0.033 (0.009) |

| Approximate 95% CI | (0.970, 1) | (0.009, 0.044) | (0.014, 0.069) | (0.040, 0.092) | (0.014, 0.052) |

Estimated rate based on logistic-normal random effects model; SE based on delta method

Between-study variance component estimated as 0; Results reflect overall rate across studies

Ten out of 13 studies commented on reoperation following robotic sacrocolpopexy. The most common reason for reoperation was recurrent prolapse with a combined estimated rate of 3.3% (95%CI 1.4–5.2%) with the majority being posterior repairs for non-apical prolapse. The rates of reoperation for recurrent apical and non-apical prolapse were 0.8% and 2.5% respectively. Of the 8 apical recurrences after RSC, two were managed by sacrospinous ligament fixation and one with a total vaginal mesh repair.20, 23–24 The second most common reoperation following robotic assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy was mesh revision with a rate of 1.7%.

The reporting of subjective data was heterogeneous. Only five studies reported results of validated questionnaires with improvement of the scores in each cohort. Geller et al25 reported mean scores for the Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory (PFDI), Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire (PFIQ), and Pelvic Floor Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ) preoperatively and at 12-month follow up with the following respective values: 117 vs 38, 60 vs 10, and 34 vs 36. In Geller et al’s 2012 study19, average PFDI, PFIQ, and PISQ, scores were reported at 44-month mean follow up with the following values: 61.0, 19.1, and 35.1 respectively. Matthews et al26 reported that collection of validated questionnaires was ongoing at the time of publication. Mourik et al20 used a Dutch variation of the Urinary Distress Inventory and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire. In their study, they reported an 88.1% satisfaction rate and 78.6% rate of sexual activity at 6–8 weeks postoperatively. Paraiso et al22 reported average PFDI, PFIQ, and PISQ scores preoperatively and at on year (128 vs 44, 63 vs 0, 20 vs 16 respectively). Seror et al27 reported an improvement in the average PFDI score from 160 to 27 postoperatively but did not differentiate between the RSC and LSC cohort. Siddiqui et al14 reported mean scores 12 months postoperatively: Pelvic Organ Distress Inventory 10.2, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Impact Questionnaire 0.7, and PISQ 36. Seven studies reported postoperative patient satisfaction >90%; however the methods of reporting were highly variable.

Discussion

The use of robotic assisted surgery in the field of gynecology is increasing rapidly in the United States. A recently published population based analysis of greater than 250,000 patients demonstrated that the rate of robotic assisted hysterectomy increased from 0.5% to 9.5% between 2007 and 2010.28

Our review of the literature on robotic assisted sacrocolpopexy showed the majority of publications were small case series. Only in the past few years have larger prospective cohort studies and a single randomized controlled trial been published. Because of the increase in complications reported with transvaginal mesh for prolapse, it is likely that many pelvic floor surgeons are abandoning a transvaginal approach and looking for a minimally invasive approach with similarly high efficacy.29 Thus we would expect robotic assisted sacrocolpopexy to continue to increase in popularity. Because randomized controlled trials are difficult to perform when assessing surgical procedures and uncommon with new procedures and technologies, the systematic review of available data is necessary.

To our knowledge, this study is the first systematic review of robotic assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy. Our analysis demonstrates that robotic assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy is a safe and effective procedure for apical prolapse with low recurrence rates. The anatomic cure rate of 98.6% at a mean follow-up of 26.9 months mirrors that of the traditional abdominal sacrocolpopexy performed by laparotomy at medium-term follow up.3 Notably there was little variance in anatomic cure rates at or beyond six months between the studies, yielding narrow confidence intervals and suggesting our combined estimate for the anatomic cure rate is valid. Paraiso et al22 who published the only randomized controlled trial among the selected studies reported the lowest apical anatomic cure rate at 88.4%. However, the majority of their patients (72%) had advanced prolapse of POP-Q Stage 3 or 4.

Interestingly, the majority of prolapse recurrences were non-apical, and transvaginal posterior repair was the most common procedure performed for recurrent prolapse. This finding may suggest that in patients with a significant posterior compartment defect, posterior repair may be indicated at the time of RSC in order to avoid future reoperation. However, based on the studies included in this review, it is not known if posterior defects were present at the time of RSC or if they developed de novo. RSC is traditionally indicated for apical and/or anterior vaginal prolapse and therefore asymptomatic posterior defects may not have been addressed at the initial surgery. Recurrent apical prolapse was significantly less common. Of the 15 apical recurrences, the majority were managed conservatively and those who underwent reoperation were treated with vaginal apical repairs.

Total operative time and estimated blood loss varied widely among the studies; however, this may partially be explained by the number of concomitant procedures, surgeon experience, prior surgery, body mass index, and the complexity of the cases. The average length of stay (2.4 days) was longer than expected for a minimally invasive procedure. However, only three studies reported an average hospital stay of greater than three days. Notably, these studies were performed in Hong Kong, France, and Spain.24,27,30 Variation in healthcare management among different countries may partially account for the longer hospital stays in these studies. Many of the included studies were performed early in the surgeons’ implementation of the robotic technique which may also contribute to the longer than expected length of stay. The complication rate was overall low and consistent with reported surgical complication rates for laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy.7 Similar to operative time and blood loss, complication rates may vary based on factors such as surgeon experience, patient BMI, and previous pelvic surgery. Our analysis was not able to control for these factors. Matthews et al26 reported that in their series of 85 patients, all six visceral injuries occurred in patients with previous pelvic surgery. Three studies excluded patients with previous pelvic reconstructive surgery20,22,30 while three studies included only patients with prior hysterectomy22,24,31. The differences in the selection of patients for these studies demonstrate that selection bias is a limitation of meta-analyses and may account for our finding that RSC is associated with low complication rates.

Our estimated mesh exposure/erosion rate of 4.1% is slightly higher than the rates seen in the abdominal procedure (3.4%)3 and the laparoscopic procedure (2.7%)7 at medium-term follow up. Paraiso et al22 was the only study to specify that one of the two mesh erosions reported in their study was from a synthetic sling instead of the sacrocolpopexy mesh. However, based on the locations reported in other studies including the posterior vagina (6), apex (3) and anterior vagina (2), the majority of mesh erosions appear to be related to the sacrocolpopexy mesh.

11 of 13 studies reported use of a standard macroporous monofilament polypropylene mesh for the sacrocolpopexy. Notably, Moreno et al30 used an acellular collagen coated polypropylene mesh and reported no mesh erosions. Shariati et al21 report a technique using a porcine dermis overlay with polypropylene mesh anchored with a non-absorbable multi-filament suture which may partially explain the higher rate of mesh erosion (11.2% of patients with > 6 month follow up).. If the mesh exposure/erosion rate is truly higher in RSC, the lack of haptic feedback may be one theory to explain this finding. The lack of haptics may lead to inadvertent thinning of tissue during the vaginal dissection or deeper placement of sutures perhaps leading to higher rates of mesh or suture exposure/erosion within the vagina. Mourik et al20 was the only uterine-sparing RSC study that met inclusion criteria, and notably no mesh erosions were reported. Matthews et al26 also noted that mesh exposures/erosions only occurred in their patients who underwent robotic sacrocolpopexy in contrast with sacrocervicopexy and postulated that the cervix may provide an anatomic barrier that decreases the risk for mesh exposure/erosion. The notion that colpotomy is associated with increased rate of mesh exposure/erosion with sacrocolpopexy has been suggested by others.3

Recently published data from the extended Colpopexy and Urinary Reduction Efforts (eCARE) has provided long-term outcome data on patients after abdominal sacrocolpopexy.32 Initially designed as a randomized controlled trial to study effectiveness of concomitant Burch colposuspension at the time of abdominal sacrocolpopexy, the original study follow-up was extended to also assess long-term anatomic and symptomatic recurrence of prolapse. They report anatomic failure rates of 22% in the ASC group and 27% in the ASC with Burch colposuspension group at 7 years; however, the reoperation rate for recurrent prolapse remained low at 5%. They report an overall mesh erosion of 10.5% at 7 years after abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Notably, the type of material used was not standardized and included autologous grafts, xenografts, as well as mono- and multi-filament synthetic grafts.33 Based on this data, it is presumed that the rates of anatomic failure and mesh erosion may increase as longer term outcome data becomes available for robotic sacrocolpopexy.

In the studies there was a relatively low reporting of validated pelvic floor questionnaires. A likely explanation for this is the inclusion of retrospective studies in our review. Five of the six prospective studies discussed use of validated questionnaires in contrast to only one of seven retrospective studies. Increased use of these questionnaires would allow better assessment of subjective and patient-directed outcomes for future studies. Sexual function is an important component of reconstructive surgery and has a significant impact on quality of life.34 Only Shariati et al21 commented on postoperative dyspareunia with a rate of 9.6% at one year. Inclusion of objective and validated measurements of sexual function both before and following RSC is needed.

Limitations of our study are similar to any meta-analysis and include varying quality, selection bias, and possible publication bias within the studies. There was also significant loss to follow up with a wide variation among the studies that may introduce bias within our results. Other potential sources of error in our analysis are the differences in severity of preoperative prolapsed stage/grade, experience of the surgeon and facility with robotics and the technical portions of the procedure.

While long-term randomized controlled trials comparing robotic assisted laparoscopic to traditional laparoscopic approach are needed, the outcomes of this systematic review and meta-analysis indicate that at medium-term follow-up (> 6 months), robotic sacrocolpopexy is an effective surgical treatment for apical prolapse with high anatomic cure rate and low rate of complications.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: No funding was received for this work.

Dr. Lyles’ work was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR000454. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

The findings were presented orally at the 2012 International Urogynecology Association Scientific Meeting, September 4–8, 2012 in Brisbane, Australia.

The findings were presented in poster format at the 2012 American Urogynecologic Society Annual Scientific Meeting, October 3–6, 2012 in Chicago, Illinois.

References

- 1.Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in U.S. Women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1278–1283. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c2ce96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JS, Waetjen LE, Subak LL, Thom DH, Van Den Eeden S, Vittinghof E. Pelvic organ prolapse surgery in the United States, 1997. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:712–716. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nygaard IE, McCreery R, Brubaker L, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy: a comprehensive review. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:805–823. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139514.90897.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iglesia CB, Hale DS, Lucente VR. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy versus transvaginal mesh for recurrent pelvic organ prolapse. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1918-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maher C, Feiner B, Baessler K, Adams EJ, Hagen S, Glazener CM. Surgical management of pelvic organ prolapse in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD004014. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004014.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman RM, Pantazis K, Thomson A, et al. A randomised controlled trial of abdominal versus laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of post-hysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: LAS study. Int Urogynecol J. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00192-012-1885-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ganatra AM, Rozet F, Sanchez-Salas R, et al. Eur Urol. Vol. 55. Switzerland: 2009. The current status of laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: a review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wells G, Shea B, O'Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 11.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/STAT 9.2User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller EJ, Siddiqui NY, Wu JM, Visco AG. Short-term outcomes of robotic sacrocolpopexy compared with abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112:1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818ce394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elliott DS, Krambeck AE, Chow GK. Long-Term Results of Robotic Assisted Laparoscopic Sacrocolpopexy for the Treatment of High Grade Vaginal Vault Prolapse. Journal of Urology. 2006;176:655–659. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siddiqui NY, Geller EJ, Visco AG. Symptomatic and anatomic 1-year outcomes after robotic and abdominal sacrocolpopexy. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;206:435.e1–435.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimko M, Umbreit E, Chow G, Elliott D. Long-term durability of robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy with a minimum of three years follow up. Journal of Urology. 2010;183:e535–e536. doi: 10.1007/s11701-011-0244-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bedaiwy MA, Abdel Rahman M, Pickett SD, Frasure H, Mahajan ST. The impact of training residents on the outcome of robotic-assisted sacrocolpopexy. Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery. 2011;17:S26. doi: 10.1155/2012/289342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Luber KM, Nager CW, Lukacz ES. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. Vol. 17. United States; 2011. Robotic-assisted and laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: comparing operative times, costs and outcomes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer BA, Whelan CM, Powell TM, Schwartz BF. Robot-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy as management for pelvic organ prolapse. J Endourol. 2009;23:655–658. doi: 10.1089/end.2008.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geller EJ, Parnell BA, Dunivan GC. Robotic vs abdominal sacrocolpopexy: 44-month pelvic floor outcomes. Urology. 2012;79:532–536. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mourik SL, Martens JE, Aktas M. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse using robot assisted laparoscopic. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165:122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shariati A, Maceda JS, Hale DS. Da Vinci assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy: Surgical technique on a cohort of 77 patients. Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery. 2008;14:163–171. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paraiso MF, Jelovsek JE, Frick A, Chen CC, Barber MD. Laparoscopic compared with robotic sacrocolpopexy for vaginal prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:1005–1013. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318231537c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson AD, Kramer BA, Wayment RO, Schwartz BF. Supracervical robotic-assisted laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ. Jsls. 2010;14:525–530. doi: 10.4293/108680810X12924466008006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan SS, Pang SM, Cheung TH, Cheung RY, Chung TK. Laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy for the treatment of vaginal vault prolapse: with or. Hong Kong Med J. 2011;17:54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geller EJ, Parnell BA, Dunivan GC. Pelvic floor function before and after robotic sacrocolpopexy: one-year outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2011.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews CA, Carroll A, Hill A, Ramakrishnan V, Gill EJ. Prospective evaluation of surgical outcomes of robot-assisted sacrocolpopexy. South Med J. 2012;105:274–278. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318254d0c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seror J, Yates DR, Seringe E, et al. Prospective comparison of short-term functional outcomes obtained after pure. World J Urol. 2012;30:393–398. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0748-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright JD, Ananth CV, Lewin SN, et al. Robotically assisted vs laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with benign gynecologic disease. JAMA. 2013;309:689–698. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.FDA Safety Communication: Update on Serious Complications Associated with Transvaginal Placement of Surgical Mesh for Pelvic Organ Prolapse. Administration FaD, ed. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00192-011-1581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreno Sierra J, Ortiz Oshiro E, Fernandez Perez C, et al. Long-term outcomes after robotic sacrocolpopexy in pelvic organ prolapse. Urol Int. 2011;86:414–418. doi: 10.1159/000323862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shveiky D, Iglesia CB, Sokol AI, Gutman RE. Robotic sacrocolpopexy versus vaginal mesh colpopexy for treatment of anterior and apical prolapse - A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Pelvic Medicine and Surgery. 2009;15:57. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nygaard I, Brubaker L, Zyczynski H, et al. Long-term outcomes following abdominal sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. JAMA. 2013;309(19):2016–2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brubaker L, Cundiff GW, Fine P, et al. Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with Burch colposuspension to reduce urinary stress incontinence. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1557–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pauls RN, Silva WA, Rooney CM, et al. Sexual function after vaginal surgery for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:622.e1–622.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]