Abstract

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in all racial and ethnic groups. Although CRC screening is very cost-effective, screening rates are low among most ethnic groups, including Asian Americans. Given the high use of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) among Chinese Americans one potentially useful approach to promote CRC screening in these communities could involve TCM providers in outreach efforts.

Methods

A two-phase study was conducted. The perceived suitability of TCM providers in CRC prevention was explored in Phase 1. Guided by Phase 1 findings, in Phase 2, a 38-page integrative educational flipchart was developed and tested. Focus groups and observations were conducted with TCM providers (acupuncturists and herbalists) and with limited English proficient Chinese American immigrants living in San Francisco, California.

Results

In Phase 1, the role of TCM providers as CRC screening educators was deemed acceptable by both providers and community members, although some providers had reservations about engaging in CRC outreach activities due to lack of expertise. The majority of providers were not aware of regular CRC screening as a preventive measure, and most were not up-to-date in their own screening. In Phase 2, the integrative CRC education flipchart was perceived as culturally appropriate based on stakeholder input and feedback.

Conclusion

This study shows that TCM providers have the potential to be a valuable and culturally appropriate community resource for providing information on CRC screening. It suggests a potential role for traditional healers as change agents in the immigrant community health network.

Keywords: Chinese American, Colorectal Cancer, Preventive Screening, Public Health Education, Integrative Medicine

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, after heart disease [1]. Among Asian Americans, however, it remains the leading cause of death [2,3]. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer among men and women in all racial and ethnic groups [4]. Although CRC screening is a very cost-effective resource, screening rates are low among most ethnic groups, including Asian Americans [5–6]. One potentially useful and culturally appropriate approach to promote CRC screening in ethnic communities could be to involve traditional healers in outreach.

Chinese Americans constitute the largest Asian American population in both the United States and in California [7–8]. Use of Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) by Chinese Americans is relatively high. The 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) found that 4.1% of adults had used acupuncture at some time [9], and that Asian American females were significantly more likely to have used acupuncture within the previous year compared with other groups [10]. A national telephone survey of 804 Chinese American women reported that 41% used TCM [11]. A survey of 3,258 Chinese and Vietnamese Americans reported TCM use by 66% of the respondents [12]. Nearly all of 198 Chinese immigrants in 2 community clinics in San Francisco reported TCM use during the previous year, mostly for fatigue, pain, and prevention. Self-medication with herbal medicines was the norm (43% reporting weekly use), with another 23% using herbs prescribed by a TCM provider, and 14% receiving acupuncture treatment [13].

Since many Chinese Americans consult TCM providers, engaging those providers in health promotion may represent a significant opportunity to improve health in the community. The TCM providers have established social networks, share language and cultural beliefs with community members, and are seen as credible health experts. Numerous studies outside of the United States have examined the integration of traditional healers into public health efforts and found beneficial changes in the attitudes and behaviors of both traditional providers and the community members receiving outreach from them. Representative studies found positive outcomes related to birthing practices, sanitation and hygiene, HIV care, water treatment, oral rehydration therapy, and nutrition education [14–18].

Although there is an increasing use of traditional healing methods, like acupuncture, in integrative medical practice in the US [19–21], there is very limited research on the use of traditional healers in community-based public health outreach. One study reported on a hepatitis B virus education program with TCM providers in California. Over 1,000 providers participated, and their understanding of hepatitis B increased significantly after the training. This study suggests that traditional providers are interested in contemporary community public health issues [22].

Thus, this study was conducted to explore an understudied concept of incorporating traditional healers in community public health education. The goal was to gain greater understanding of whether TCM providers would be interested in participating in a CRC screening program and to examine culturally appropriate ways to include them in public health outreach efforts.

METHODS

The study was conducted in two Phases. Phase 1 was to determine if TCM providers would be interested in providing a CRC screening education program to their clients and if their clients would view TCM providers as appropriate channels of such biomedical-oriented preventive information. Phase 2 focused on the development of a CRC education flipchart that integrated traditional and biomedical concepts suitable for use by TCM providers.

Participant Inclusion Criteria and Recruitment

The study was conducted in San Francisco, California, home to one of the largest Chinese American communities in the United States. Phase 1 participants included 14 TCM providers and 14 TCM clients. Two focus groups were conducted with providers (7 each) and two with clients (7 each). The group size of 7 participants, a typical size for community focus groups, was chosen to be large enough to include a diversity of opinions but small enough to provide opportunity for all members to participate in the discussions and exchange ideas.

TCM providers were recruited through local Chinese acupuncturist and herbalist professional associations. Eligibility requirements for TCM providers were having at least 10 years of experience of serving the Chinese American community. The response rate for TCM providers was 70% and the most common reason for nonparticipation was time conflict. TCM clients were recruited through advertisement in a local Chinese newspaper or through recommendations from TCM providers. Eligibility requirements for TCM clients were that they were Chinese Americans, aged 50 years or older, who spoke Chinese (Cantonese or Mandarin), and reported receiving health advice or health care from TCM providers during the past 12 months.

The Phase 2 participants were aged 50 and older and included 7 TCM clients (who reported using TCM for health care purposes during the past 12 months) and 7 non-clients (never or no use of TCM within 12 months). They were all recruited from advertisements in a local Chinese newspaper. The response rate for TCM clients was not available since they were recruited through the newspaper. Participants were unique in all Phase I and II focus groups, there was no commingling.

Procedures and Data Analysis

In Phase 1, two focus groups were conducted with TCM providers in October 2008 and January 2010 to explore provider perspectives on cancer and cancer prevention, especially CRC screening. One group consisted of 7 acupuncturists and the other had 7 herbalists. Three of these TCM providers (2 acupuncturists and 1 herbalist) were also selected for ethnographic observation in their places of business to assess whether their worksites and work schedules were appropriate for CRC educational activities. These 3 providers were observed by a team member who was a bilingual anthropologist trained in TCM. Two additional focus groups were conducted with TCM clients in March 2010. The purpose was to assess client CRC beliefs and their attitudes about the suitability of TCM providers as CRC educators.

During Phase 2, an educational flipchart and a training program on CRC screening and prevention were developed for TCM providers. Experts in TCM, biomedicine, psychology, public health, and health education with Asian American populations developed the flipchart and training program. Findings from Phase 1 were used to guide the development of the materials and additional input was obtained from two other TCM providers. In January 2012 the completed flipchart was reviewed by two focus groups. Each group was comprised of 7 individuals and included both TCM clients and non-clients. All Phase I and II focus groups were conducted in Chinese and audiotaped for verification purposes, but not transcribed. A note-taker also took detailed notes during each meeting.

Findings from focus groups and ethnographic observations were analyzed using thematic analysis of content related to provider and client attitudes and beliefs about CRC preventive screening, TCM beliefs and practices, and thoughts on cancer etiology specifically. The intent was to work with both lay and expert community members to gain a more culturally representative understanding of CRC, its prevention, and the role of prevention messaging from an integrative medical perspective. Table 1 provides examples of the key questions used to guide discussions with the focus groups.

Table 1.

Sample focus group questions

| Phase 1: Focus group questions for TCM providers |

|

I. General questions for TCM providers regarding work and health perspectives What’s your weekly working schedule? How many customers do you have every day? |

|

II. Feasibility of participating in the LHW project If you advise your customers to look into cancer prevention tests using Western medicine, such as the FOBT or colonoscopy test, would they accept your advice? Do you think they would like to receive this type of information from you? Why or why not? |

|

III. TCM providers’ opinions on cancer and colon cancer prevention Have you heard of a Fecal Occult Blood Test (also known as an FOBT), or a colonoscopy test, or other colon cancer screening tests? |

| Phase 1: Focus group questions for TCM clients |

|

I. Client views on health and healthcare, treatment and prevention When you don’t feel well, what kind of self-care remedies do you use? Over-the-counter from the western drugstore, Chinese herbs from local herb shop, or other? |

|

II. Client views on cancer prevention and colon cancer prevention Have you heard or ever done any of these tests: Fecal Occult Blood Test (also known as an FOBT), colonoscopy test, or other colon cancer screening tests? |

|

III. Client views on Chinese medicine doctors as cancer prevention educators If your Chinese medicine doctor were to suggest that you look into biomedical cancer prevention tests, such as the FOBT or colonoscopy test, would you accept the advice? Would you like to receive this type of information from him/her? Why or why not? |

| Phase 2: Focus group questions on the integrative flipchart |

|

I. Flipchart appearance What did you like, the message, graphics/pictures, layout, wording, other? |

|

II. Flipchart messaging What was the overall message of the flip chart? |

|

III. Flipchart impact What do you think about colon cancer screening now that you have seen the flip chart? |

RESULTS

Phase 1: TCM Providers as CRC Screening Educators – Provider Perspective

TCM Provider Demographics

All 14 TCM providers were first generation immigrants from either Mainland China or Hong Kong with ages ranging from 40–72 years (median age = 54). Three of the acupuncturists were female, while the herbalists were all male. All of the acupuncturists had a college degree in TCM either from Mainland China or America, five herbalists had a college degree in TCM from Mainland China and two herbalists from Hong Kong were trained through mentorship. The majority (n=9) worked in San Francisco’s Chinatown. The acupuncturists reported seeing from 2–10 clients per day depending on where they practiced, while the herbalists reported seeing 20–30 clients per day.

TCM Provider Cancer Beliefs

All of the TCM providers emphasized that TCM had many advantages in treating chronic and serious diseases including cancers. TCM providers stated that there was no single cause of cancer. For example, in TCM theory the causes of cancer include toxins, emotional stress, and stagnation of qi and blood. For CRC, the TCM providers suggested a variety of causes including lifestyle, weak body (deficient qi), poor diet, and stress from work. Although somewhat vague, this kind of explanation was described as making sense to clients and as less threatening than the explanations given in biomedicine. As one provider said, “It’s easy to be understood and less scary to talk about cancer in TCM language.” Of note, only 6 out of 14 TCM providers (43%) had themselves used any of the recommended CRC screening tests, and only two of them were up to date. Both the herbalists and acupuncturists held similar beliefs based on TCM theory about the causes of cancer.

TCM Provider Attitudes Regarding Educating Patients About CRC Screening

Providers reported that offering health advice or education to their patients was common, including information on both presenting complaints as well as prevention concepts. Most of the advice was based on the patients’ individual needs in relation to their specific health problems. None of the TCM providers had ever mentioned CRC screening tests to their patients, such as fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) or colonoscopy. They were also not familiar with the concept of CRC screening as a preventive measure. Two of the providers stated that colonoscopy was useful for CRC diagnosis. For example, a male acupuncturist who had worked for more than 20 years in the Bay Area said “If they have an illness related with colon for a long time and difficult to cure, I will suggest them to do a colonoscopy.” A similar statement was made by an herbalist. In addition, some herbalists stated that they were too busy with their routine work to offer this kind of health advice. They also stated that they did not have the position or authority to give biomedical advice. A male herbalist said, “ I don’t have a reason to tell my patients about these tests,” and “If they don’t have any symptoms, why should I tell them to do colonoscopy? It’s a tough examination.”

When asked what they would think if they were asked to promote CRC screening with patients, the responses varied. Most acupuncturists reported that they would not mind delivering screening information if they were asked. A male acupuncturist said, “Patients like to learn more. If they have time and want to listen, I can talk about it.” In contrast, herbalists had more concerns. One herbalist remarked, “If I tell them (about CRC screening), patients would think that they already got a serious problem. They will be scared. Even if I explain that this is prevention, they won’t believe me and still think it’s a serious issue.”

Both acupuncturists and herbalists preferred an indirect approach for promoting CRC screening, such as putting a brochure or poster about CRC screening in their clinics or stores. They also expressed some reluctance to offer a formal class on the topic. One female acupuncturist said, “I think public education is better than us, such as Chinese newspaper or TV programs.” A male herbalist commented, “It seems strange if we lecture CRC to our patients. But it’s okay to give brochures or put up a poster about CRC screening in my store.”

The ethnographic observations, by comparison, showed that TCM providers actually used more biomedical information in their practices than they indicated in focus group meetings. For example, in one clinic observation the male acupuncturist drew a diagram of the kidneys and stated that the kidneys were involved in blood circulation and that the adrenal gland provided energy. Yet they usually gave more detailed explanations from a TCM perspective. The TCM clients were very attentive to what the providers said about their conditions, treatment strategies, and daily lifestyle suggestions. They often eagerly engaged in the discussion of the causes of their ailments and what they should do to avoid other complications. The atmosphere was generally friendly and relaxed.

Phase 1: TCM Providers as CRC Screening Educators -- Client Perspective

TCM Client Demographics

The 14 TCM clients’ ages ranged from 50–68 years (median age = 57), with equal numbers of males and females. All were first generation immigrants from Mainland China with diverse educational backgrounds. Most (n = 13) lived in the city of San Francisco and had limited English proficiency.

TCM Client Traditional Medicine Use and Beliefs

Use of TCM, especially herbal preparations, was reported to be the first level of care employed by all of the clients. The local herbalists are a fixture in the community and provide readily accessible and affordable consultations and advice. Although herbs were not covered by any health insurance, all 14 clients reported that when they did not feel well, or had signs of getting sick, that they always took herbal products first, either through self-prescribing or consulting with a TCM provider at an herb store. Because acupuncture was more expensive than herbs, they would typically see acupuncturists when the service was covered by insurance or when they believed the condition was better treated by acupuncture. They usually selected their TCM providers based on years in practice (the more years of practice the better) and recommendations from friends. One female participant said, “I have known the herbalist for many years and he took care of my whole family.” In addition, half of the participants claimed that they had some basic knowledge about Chinese herbs and often treated themselves with herbs or medicinal foods at home. They reported that taking Chinese medicine was not only for treating illness but also for restoring the balance of the whole body.

TCM Client Cancer Beliefs

TCM client participants viewed the main causes of cancer to be polluted air and water, poor diet, stress, and a weak body, sometimes described as deficient qi (vital life force). The majority thought that cancer was preventable and that its prevention was not very different from preventing general illness. When asked specifically how to prevent colon cancer, most clients listed healthy diet, regular bowel movement, and positive emotion as the most effective methods. A female client emphasized, “Food is most important. Eating balanced food with regular bowel movement is the key to prevent colon cancer.” One male client stated, “Cancer is unpredictable and nothing could guarantee preventing cancer.” Most of the clients were not familiar with the concept of CRC screening as a preventive measure. Although 10 (71%) had been screened using either fecal occult blood tests (FOBT) or colonoscopy, only one mentioned that colonoscopy was a preventive measure against colon cancer.

TCM Client Attitudes Toward TCM Providers Offering CRC Screening Education

In general, TCM clients stated that they would like to hear health advice from TCM providers including biomedical perspectives on cancer prevention. One male participant stated, “Of course we want to know more about cancer prevention regardless of whether it’s Chinese or Western medicine.” When asked from whom they would like to learn about CRC screening, the order was Western medicine doctors, TCM providers, family members, and friends. When asked how they would feel about receiving CRC screening advice from a TCM provider, one male participant said that he would listen to the acupuncturist about CRC screening after the provider felt his pulse, because he knew then that the advice would be based on his condition. A female herbalist client stated that if a TCM provider suggested CRC screening to her it would suggest that there was something likely wrong with her colon.

Phase 2: Development and Evaluation of an Integrative CRC Screening Educational Flipchart

Flipchart Development

The focus group and observational findings showed that there was some willingness among both TCM clients and providers to have TCM providers deliver messages about CRC screening, although the providers had some reservations related to patient interpretation of the message. Both providers and clients held similar beliefs about cancer etiology and prevention and a misunderstanding of a key role of CRC screening tests as a preventive measure rather than just diagnostic. These findings provided support for the development of a culturally appropriate CRC screening educational resource. A previously evaluated 44-page CRC flipchart designed to be delivered by lay health workers [23] was determined to be a suitable starting platform for the TCM CRC education resource. Although biomedically-oriented it had been developed with significant community input and had been well received by diverse audiences.

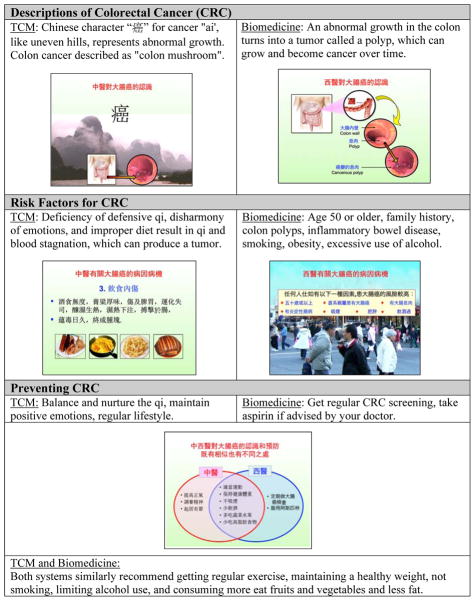

Based on the original CRC flipchart, an integrated (TCM and biomedical) version was created with input from a bicultural and bilingual team, including an acupuncturist and herbalist from the Phase 1 focus groups. The flipchart contained information on the similarities and differences between TCM and biomedical views of colon cancer, including causes, the role of CRC screening, and cross-cultural views of prevention, including excerpts from traditional Chinese classics on health and longevity. The flipchart showed that there were similarities as well as differences between the two medicines in terms of CRC explanation and prevention. A major goal of the flipchart was to show the relationship between the two medicines, the important role of prevention in both worldviews, and the wisdom of taking the best of what both of them had to offer. Figure 1 is a summary of key integrative CRC concepts with representative Chinese pages from the flipchart.

Figure 1.

Sample pages, integrative CRC screening educational flipchart

Focus Group Participant Demographics

Preliminary evaluation of the flipchart was done using two 7-member focus groups comprised of both TCM clients and non-clients (n=14). Participants’ ages ranged from 50–78 years (median age = 62), with 6 males and 8 females. All were first generation immigrants from Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan with limited English proficiency and diverse educational backgrounds.

Preliminary Evaluation of the Integrative CRC Screening Educational Flipchart

After viewing the flipchart, the majority of focus group participants said that screening for CRC was important because biomedical testing was more precise and reliable for detecting abnormalities. They stated that a combined TCM-biomedical approach was best for the prevention of colon cancer because each had its own strength. One female non-TCM user participant stated that, “The two medicines are complementary to each other...this is the best way.” None of the participants thought it was contradictory or confusing to have the two medical perspectives presented together. Comments included, “The ideas are natural and make sense,” and that the flipchart was “easy to understand.”

DISCUSSION

Acceptance of TCM Providers as CRC Screening Educators

Based on focus group discussions and provider observations, it was clear that TCM providers and clients were open to having TCM providers communicate messages about biomedical approaches to health and CRC prevention. TCM providers were already engaged in preventive education with their clients, sharing TCM ideas on healthy diets and positive emotion, and some biomedical information as well. The inclusion of biomedical information is actually not unusual among TCM providers who received formal training in Mainland China since 1949. Under the Chinese State’s policy of modernization of TCM and developing integration of TCM and Western medicine, the curriculum of TCM colleges included instruction in western biomedical concepts and some basic procedures [24]. Although some TCM providers in the United States may have been trained in Hong Kong where there was no formal training in biomedicine before 1997, a significant proportion of TCM providers in this study had attended a TCM college in Mainland China and thus were likely to have been exposed to biomedical concepts in their training.

Clients also expressed support for the integrative flipchart, for example, saying that the “two medicines are complementary to each other.” Indeed, most Chinese immigrants, especially those from Mainland China, are very familiar with this integrative approach, given the fact that the provision of integrative medicine (TCM & Western medicine) has been common in Mainland Chinese hospitals and various health care service centers for decades [25, 26]. In addition, medical anthropologist studying healthcare utilization in China have observed that patients in China tend to retain significant control of their disease management in terms of deciding whether to use traditional or modern methods [27]. Positive feedback about the CRC flipchart and its integrative CRC prevention message reflects this integrative view.

Challenges for TCM Providers Promoting CRC Screening

The high acceptability of the integrative flipchart indicates that having TCM providers teach their clients about preventive care using both biomedicine and TCM views is feasible and potentially effective, but challenges remain. While clients were willing to listen to TCM providers on this topic, some providers felt that it was not their role, or that they were too busy at work to conduct such training. This was confirmed during ethnographic observations, particularly with the herbalists. In addition, many of the providers had not been screened, indicating a lack of knowledge about the preventive benefits of screening, or potentially suggesting that certain traditional health beliefs presented barriers to screening. For example, both TCM providers and clients mistakenly thought that the CRC tests were useful in diagnosis, not prevention. Research on cancer screening in New York’s Chinatown among Chinese immigrants found a similar lack of understanding of screening as a preventive measure and a low rate of utilization of screening methods [28]. A study on beliefs regarding causes of CRC among a sample of Canadian Chinese immigrant women noted related misunderstandings [29].

Another challenge facing providers may be certain linguistic and cultural factors affecting understanding of CRC screening as prevention. When asked how they would feel about receiving CRC screening advice from a TCM provider, one client said that he would listen to the TCM providers about CRC screening after the provider felt his pulse, because he knew then that the advice would be based on his condition. Since pulse reading is used diagnostically, the implication of reading a pulse and then suggesting getting CRC screening could be that there is a problem. This is the basic concern the providers shared about educating their patients about CRC screening. Indeed, one of the TCM client stated that if a TCM provider advised CRC screening to her it would suggest that there was something likely wrong with her colon. Potentially contributing to this issue is that the concept of prevention, or yufang in Chinese, cannot be separated from the more traditional terms ‘maintaining health’ (baojian) or ‘cultivating life’ (yangsheng). Both TCM providers and clients shared the view that preventing illness involved lifestyle practices such as consuming medicinal soups, getting exercise, and regulating the emotions. In contrast, CRC screening and other biomedical tests may appear to be too painful or even harmful to the body to be accepted within this cultural view of prevention. Results from a New York Chinatown survey of immigrant Chinese revealed similar beliefs, that CRC screening could be harmful and even cause cancer [28].

A Potential Mutual Benefit to Providers and Clients

This study found that Chinese Americans view TCM providers as an important part of their personal health care networks. There is a bond of common language, culture and health beliefs. Use of TCM was quite high and viewed favorably. Ethnographic observations and focus group discussions found that TCM providers offered accessible, effective, and comforting health care services for many Chinese Americans. Their relationships with clients was more friendly than authoritarian.

Given the central role TCM providers play in the lives of the community in delivering healthcare services and health information, it would be valuable to include these individuals in public health campaigns for both the providers’ edification as well as for the benefit of their clients. Involving TCM providers in a CRC screening program and other community health initiatives would inform the providers of important preventive practices and as a consequence could increase their own utilization of such preventive measures. Other studies have shown a clear relationship between healthcare provider personal health practices and the messages they convey to their clients [15, 22]. Because of this, if TCM providers were educated and incorporated into broader public health education and outreach campaigns it could potentially encourage them to become more proactive advocates for screening and related programs. International studies on the use of traditional healers in community health education efforts have shown this dual benefit to be the case [14–18]. This study has shown that TCM providers are not only open to learn biomedicine-oriented health information, but also that they have the potential to effectively deliver preventive messages to their clients.

CONCLUSION

This study shows that TCM providers have the potential to be a valuable community-based and culturally relevant source of information on CRC screening using an integrative approach. This suggests a role for traditional healers as change agents in the immigrant community health network. The next step in this investigation is to implement training with a sample of TCM providers to deliver CRC education to their clients using the culturally appropriate TCM-biomedicine flipchart developed in this study. Future research is warranted to evaluate the impact of this form of community health promotion in the immigrant community.

Acknowledgments

This Study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant R01CA138778. Additional support was provided by the NCI’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities through Grant 1U54153499.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the presenter and does not reflect the official views of the NCI.

References

- 1.Heron M. National Vital Statistics Reports. 7. Vol. 61. CDC/National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Deaths: Leading Causes for 2009. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lcod.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCracken M, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(4):190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B U.S. National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics Reports (NVSR) Deaths: Final Data for 2007. 2010;58(19) Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/nvsr.htm#vol58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2009 Incidence and Mortality Web-based Report. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute; 2013. Available at: www.cdc.gov/uscs. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maciosek MV, Solberg LI, Coffield AB, Edwards NM, Goodman MJ. Colorectal cancer screening: health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):80–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong ST, Gildengorin G, Nguyen T, Mock J. Disparities in colorectal cancer screening rates among Asian Americans and non-Latino whites. Cancer. 2005;104(12 Suppl):2940–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H. The Asian population 2010 Census Briefs. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.NICOS Chinese Health Coalition. A Study of Health Services for Chinese Residents of San Francisco County. Nicos, Rev. 2004 Apr 30;4 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. National Center for Health Statistics. Adv Data. 2004;343:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burke A, Upchurch D, Dye C, Chyu L. Acupuncture use in the United States: findings from the National Health Interview Survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2006;12(7):639–48. doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wade C, Chao MT, Kronenberg F. Medical pluralism of Chinese women living in the United States. J Immigr Minor Health. 2007;9(4):255–67. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9038-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn AC, Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Massagli MP, Clarridge BR, Phillips RS. Complementary and alternative medical therapy use among Chinese and Vietnamese Americans: prevalence, associated factors, and effects of patient–clinician communication. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):647–53. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu AP, Burke A, LeBaron S. Use of traditional medicine by immigrant Chinese patients. Family Medicine. 2007;39(3):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoff W. Traditional healers and community health. World Health Forum. 1992;13(2–3):182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furin J, Lesotho J. The role of traditional healers in community-based HIV care in rural. Community Health. 2011;36(5):849–56. doi: 10.1007/s10900-011-9385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoff W. Traditional health practitioners as primary health care workers. Trop Doct. 1997;27 (Suppl 1):52–5. doi: 10.1177/00494755970270S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mills E, Singh S, Wilson K, Peters E, Onia R, Kanfer I. The challenges of involving traditional healers in HIV/AIDS care. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17(6):360–3. doi: 10.1258/095646206777323382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Troskie TR. The importance of traditional midwives in the delivery of health care in the Republic of South Africa. Curationis. 1997;20(1):15–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson TW. Western acupuncture in a NHS general practice: anonymized 3-year patient feedback survey. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(6):555–60. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell IR, Caspi O, Schwartz GE, Grant KL, Gaudet TW, Rychener D, Maizes V, Weil A. Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: issues in the emergence of a new model for primary health care. Archives Of Internal Medicine. 2002;162(2):133–40. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiapparelli P, Allais G, Rolando S, Airola G, Borgogno P, Terzi MG, Benedetto C. Acupuncture in primary headache treatment. Neurol Sci. 2011;32 (Suppl 1S):15–8. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0548-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang ET, Lin SY, Sue E, Bergin M, Su J, So SK. Building partnerships with traditional Chinese medicine practitioners to increase hepatitis B awareness and prevention. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(10):1125–7. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen TT, Love MB, Liang C, Fung LC, Nguyen T, Wong C. A pilot study of lay health worker outreach and colorectal cancer screening among Chinese Americans. J Cancer Educ. 2007;25(3):405–12. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0064-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths SM, Chung VCH, Tang JL. Integrating Traditional Chinese Medicine: Experiences from China. Australasian Medical Journal. 2010;3(7):385–396. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu AP, Ding XR, Chen KJ. Current situation and progress in integrative medicine in China. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 2008;14 (3):234–240. doi: 10.1007/s11655-008-240-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang J, Lee HJ, Hong SP. Comparative Survey Study on Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine in China and South Korea. The American Acupuncturist. 2013;62:8–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scheid V. Chinese Medicine in Contemporary China: Plurality and Synthesis. Durham & London: Duke University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin JS, Finlay A, Tu A, Gany FM. Understanding immigrant Chinese Americans’ participation in cancer screening and clinical trials. J Community Health. 2005;30(6):451–66. doi: 10.1007/s10900-005-7280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mcwhirter JE, Todd LE, Hoffman-Goetz L. Beliefs about Causes of Colon Cancer by English-as-a Second-Language Chinese Immigrant Women to Canada. J Cancer Education. 2011;26(4):734–9. doi: 10.1007/s13187-011-0258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]