XELOX or FOLFOX should be considered as standard treatment options for the adjuvant management of stage III colon cancer in all age groups and in patients with comorbidities.

Keywords: age groups, capecitabine, adjuvant chemotherapy, colon cancer, comorbidity, oxaliplatin

Abstract

Background

Adjuvant oxaliplatin plus capecitabine or leucovorin/5-fluorouracil (LV/5-FU) (XELOX/FOLFOX) is the standard of care for stage III colon cancer (CC); however, there is disagreement regarding oxaliplatin benefit in patients aged >70. In most analyses, the impact of medical comorbidity (MC) has not been assessed. Efficacy and safety of adjuvant XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU were compared with respect to age and MC using pooled data from four randomized, controlled trials, selected for access to patient-level MC data and including commonly endorsed and utilized regimens.

Patients and methods

Individual data from patients with stage III CC in NSABP C-08, XELOXA, X-ACT, and AVANT were pooled, excluding bevacizumab-treated patients. Patients were grouped by treatment, MC (low versus high), or age (<70 versus ≥70), and compared for disease-free survival (DFS), overall survival (OS), and adverse events (AEs). Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression controlled for gender, T stage, and N stage.

Results

DFS benefits were shown for XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU regardless of age or MC, although benefits were modestly attenuated for patients aged ≥70. Hazard ratios were 0.68 (P < 0.0001) and 0.77 (P < 0.014) for <70 and ≥70 age groups; 0.69 (P < 0.0001) and 0.59 (P < 0.0001) for Charlson Comorbidity Index ≤1 and >1 groups; and 0.70 (P < 0.0001) and 0.58 (P < 0.0001) for National Cancer Institute Combined Index ≤1 and >1 groups. OS was also significantly improved in all groups. Grade 3/4 serious AE rates were comparable across cohorts and MC scores and higher in patients aged ≥70. Oxaliplatin-relevant grade 3/4 AEs, including neuropathy, were comparable across ages and MC scores.

Conclusions

Results further support consideration of XELOX or FOLFOX as standard treatment options for the adjuvant management of stage III CC in all age groups and in patients with comorbidities, consistent with those who were eligible for these clinical trials.

introduction

MOSAIC [1, 2], XELOXA [3, 4], and NSABP C-07 [5] showed significant improvements in disease-free survival (DFS) when oxaliplatin was added to a fluoropyrimidine for the adjuvant therapy of colon cancer (CC), regardless of whether the fluoropyrimidine was infusional leucovorin/5-fluorouracil (LV/5-FU) (FOLFOX), bolus LV/5-FU (FLOX), or oral capecitabine (Xeloda®, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland) (XELOX). MOSAIC (at a minimum of 6 years' overall follow-up in patients with stage III CC) [2] and XELOXA [4] also showed an overall survival (OS) benefit for oxaliplatin-treated patients.

Adjuvant oxaliplatin-based therapy is standard of care for stage III CC [6, 7], although reports conflict on the degree of oxaliplatin benefits in elderly patients. The ACCENT project's initial analysis of MOSAIC and NSABP C-07 showed that the oxaliplatin treatment effect was preserved in patients aged <70, but not in patients ≥70, with a significant age/treatment interaction [8]; consistent with the individual trials. NSABP C-07 demonstrated a benefit in patients aged <70, but not in those ≥70 [5]. MOSAIC reported an equivocal benefit in patients aged ≥65 [2], with the point estimate of the hazard ratio (HR) very close to unity. In contrast, XELOXA found that the oxaliplatin treatment effect was preserved (albeit attenuated) compared with younger patients, in patients aged ≥65 and those ≥70 [3, 9].

As no randomized, controlled trials directly address the impact of age on adjuvant treatment outcomes for stage III CC with oxaliplatin-based therapy, this analysis pooled individual data from patients enrolled in four randomized, controlled phase III trials evaluating LV/5-FU or capecitabine ± oxaliplatin, as adjuvant therapy for resected CC: XELOXA, AVANT, X-ACT, and NSABP C-08. Trials were selected for availability of access to complete clinical datasets, allowing the scientific questions posed to be addressed using individual patient data. Complete datasets with consistent data quality are particularly important for robust medical comorbidity (MC) assessments. We did not have access to complete MOSAIC data; hence, MOSAIC was excluded. Pooling also provides sufficient statistical power to detect differences; not possible within individual trials. Finally, all trials assessed regimens that are commonly used in practice and endorsed in practice guidelines: LV/5-FU, capecitabine, FOLFOX, and XELOX. Therefore, NSABP C-07 [5] was not included.

The impact of noncancer-related comorbidity was also investigated [by Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) or National Cancer Institute Combined Index (NCI)], which influences long-term survival after definitive surgical treatment of early-stage CC [10, 11] and may be age-related. Although ACCENT assessed age's influence on the benefits of oxaliplatin, comorbidity data were not available, potentially confounding results in patients aged >70.

A comprehensive analysis of these related factors using a large patient dataset is therefore provided.

methods

study design and patients

Individual study designs have been reported previously [3, 12–15]. Patients with stage II CC (322 from NSABP C-08, 584 from AVANT) were excluded to allow comparison of the standards of care for stage III CC. TNM status was recorded and this was used to define stage III CC as being any T, and N1 or N2 [16].

Bevacizumab-treated patients were excluded because of lack of efficacy, to reduce both heterogeneity among analytic cohorts and potential confounding effects associated with bevacizumab treatment, and to be reflective of current clinical practice as outlined by treatment guidelines [3, 6, 15]. Also, complete MC data were not collected for NSABP C-08, so comorbidity indices could not be calculated for these patients.

Individual treatment groups, and those contributing to the analyses, are summarized in supplementary Figure S1.

Oxaliplatin's effect was evaluated by comparing outcomes between the XELOX/FOLFOX (XELOX, FOLFOX-4, or mFOLFOX-6) and LV/5-FU monotherapy groups. Capecitabine and LV/5-FU were not pooled to avoid potential confounding effects of efficacy differences when given as monotherapies [12]. Subgroups were stratified to compare XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU, MC score [adapted CCI and NCI low (≤1) versus high (>1)], and age (<70 versus ≥70 years).

The primary end point was DFS: time from study entry date to date of first event; recurrence (relapse), new CC occurrence, or death due to any cause. OS (time from study entry to date of death, irrespective of cause) was a secondary end point. Patients who did not have an event at the time of trial database cutoff were censored at the date they were last known to be event-free.

Safety was a secondary end point. AEs were monitored during treatment and for 28 days after the last dose of study medication, encoded according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 13.1, and graded as mild, moderate, severe, or life-threatening/fatal (grades 1–4). Multiple instances of the same AE in one individual were summarized as a single event at the greatest severity observed. Serious AE rates were also analyzed but were not flagged in NSABP C-08 [AEs were classed as serious here if they were fatal or if submitted to the Adverse Event Expedited Reporting System (AdEERS)].

statistical analysis

Analyses were carried out using SAS 8.2.

All medical conditions, active and inactive, were entered onto the medical history case report form for screening prior to the patient receiving study regimen. The recorded conditions were matched to the 13 comorbidities identified by the NCI and CCI methods. For calculating the NCI and CCI scores, the weights assigned to the 13 comorbidities (supplementary Table S1) were summed for those conditions that were present for the patient to create a total score.

Efficacy was evaluated according to assigned treatment. Safety was evaluated in the safety population (all entered patients who received at least one dose of capecitabine, 5-FU, or oxaliplatin on-study).

Cox regression estimated HRs for DFS and OS with associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and tested their differences from 1 (the null value) using the Wald test in each subgroup. Kaplan–Meier analyses were also carried out for each subgroup. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression tested for independent effects of age and of MC on oxaliplatin benefit, controlling for gender, T stage (T1–2 or T3–4), and N stage (N1 or N2).

Multivariable Cox regression also tested for oxaliplatin by age and oxaliplatin by MC interactions in separate models, controlling for the above covariables plus baseline Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status.

results

patients

The intent-to-treat population comprised 4819 patients: 1921 received LV/5-FU and 2898 received XELOX/FOLFOX (supplementary Figure S1). Distribution of ‘MC’ and ‘age’ across cohorts for LV/5-FU or XELOX/FOLFOX were, respectively: CCI ≤1, 1586 and 1588; CCI >1, 335 and 309; NCI ≤1, 1564 and 1567; NCI >1, 357 and 330; age <70 years, 1497 and 2418; and age ≥70 years, 424 and 480.

Patient demographics/disease characteristics were in general well balanced, except number of lymph nodes examined (Table 1), which was not available for X-ACT. Sensitivity analyses were, therefore, carried out in patients with ≤12 and >12 nodes examined.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and disease characteristics (intention-to-treat population)

| Characteristic | LV/5-FU (n = 1921) | XELOX/FOLFOX (n = 2898) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) [17] | ||

| Median | 62.0 | 59.0 |

| Range | 22–82 | 19–85 |

| Sex, n (%) [17] | ||

| Female | 890 (46) | 1374 (47) |

| Male | 1031 (54) | 1524 (53) |

| Race, n (%) [17] | ||

| Asian/Pacific | ||

| Islander | 134 (7) | 298 (10) |

| Black | 30 (2) | 97 (3) |

| Caucasian/white | 1734 (90) | 2447 (84) |

| Hispanic | 14 (1) | 32 (1) |

| Other | 9 (<1) | 24 (1) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) [17] | ||

| 0 | 1100 (57) | 2338 (81) |

| 1 | 336 (17) | 551 (19) |

| Unknown | 485 (25) | 9 (<1) |

| Stage, n (%) [17] | ||

| IIIA | 156 (8) | 297 (10) |

| IIIB | 1146 (60) | 1505 (52) |

| IIIC | 619 (32) | 1093 (38) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 3 (<1) |

| Primary tumor classification, n (%) [17] | ||

| T0 | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| T1 | 36 (2) | 101 (3) |

| T2 | 161 (8) | 263 (9) |

| T3 | 1442 (75) | 2124 (73) |

| T4 | 282 (15) | 407 (14) |

| Tis | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Regional lymph nodes classification, n (%) [17] | ||

| N1 | 1302 (68) | 1805 (62) |

| N2 | 619 (32) | 1093 (38) |

| Number of lymph nodes examined, n (%) [17] | ||

| ≤12 | 456 (24) | 1131 (39) |

| >12 | 483 (25) | 1757 (61) |

| Unknown | 982 (51) | 10 (<1) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 1565 (81) | 1568 (83) |

| 1 | 21 (1) | 20 (1) |

| 2 | 279 (15) | 265 (14) |

| 3 | 18 (1) | 8 (<1) |

| 4 | 32 (2) | 30 (2) |

| 5 | 3 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| 6 | 2 (<1) | 2 (<1) |

| 7 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) |

| 8 | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1001 (35) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | ||

| ≤1 | 1586 (83) | 1588 (84) |

| >1 | 335 (17) | 309 (16) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1001 (35) |

| NCI Combined Index, n (%) | ||

| ≤1 | 1564 (81) | 1567 (83) |

| >1 | 357 (19) | 330 (17) |

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1001 (35) |

[17] Reprinted from The Lancet Oncology, 15, Schmoll HJ, Twelves C, Sun W, O'Connell MJ, Cartwright T, McKenna E, Saif MW, Lee S, Yothers G, Haller D, Effect of adjuvant capecitabine or fluorouracil, with or without oxaliplatin, on survival outcomes in stage III colon cancer and the effect of oxaliplatin on post-relapse survival: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from four randomised controlled trials, 1470–2045, Copyright (2014), with permission from Elsevier.

5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FOLFOX, leucovorin, fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin; LV, leucovorin; NCI, National Cancer Institute; Tis, carcinoma in situ; XELOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.

Median duration of follow-up was 36 months in NSABP C-08, 50 months in AVANT, 83 months in XELOXA, and 74 months in X-ACT.

efficacy

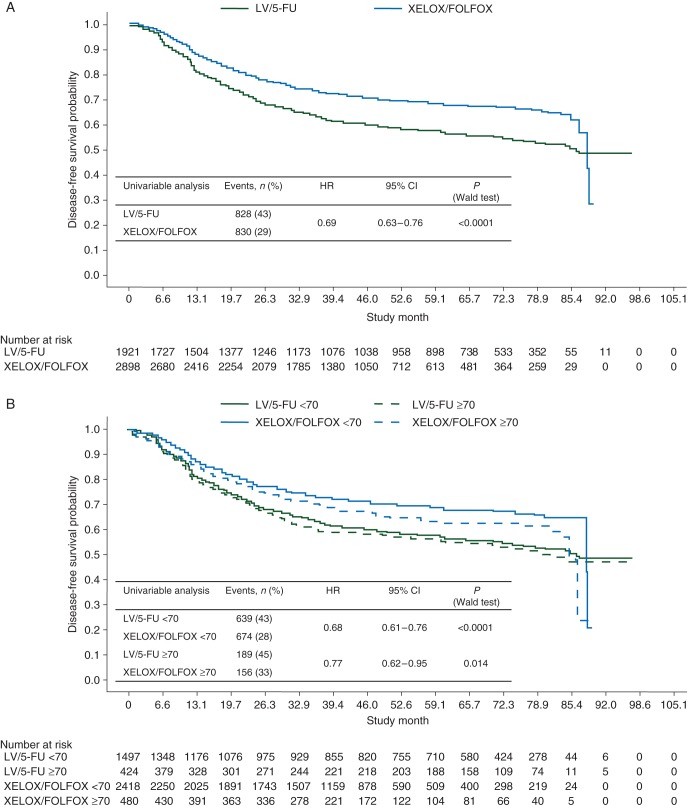

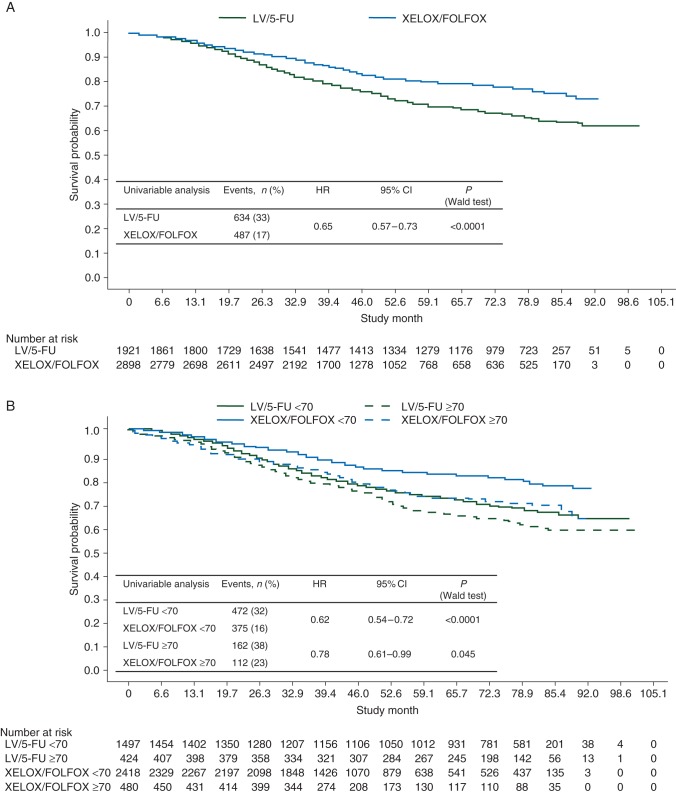

A DFS benefit was shown for oxaliplatin, independent of age or MC (Figure 1). Significantly fewer patients experienced an event with XELOX/FOLFOX. A significant oxaliplatin treatment benefit was seen in both age cohorts, but was modestly attenuated in patients aged ≥70. MC did not appear to impact the oxaliplatin benefit. The HR of XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU was consistent in patients with ≤12 and >12 lymph nodes examined [HR, 0.73 (95% CI 0.61–0.87; P = 0.0005) and HR, 0.78 (95% CI 0.66–0.92; P = 0.0036), respectively].

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots of disease-free survival (A) for the intention-to-treat population, (B) by age (<70 versus ≥70 years), (C) by Charlson Comorbidity Index (≤1 versus >1), and (D) by National Cancer Institute Combined Index (≤1 versus >1). 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; FOLFOX, leucovorin, 5-fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin; LV, leucovorin; XELOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.

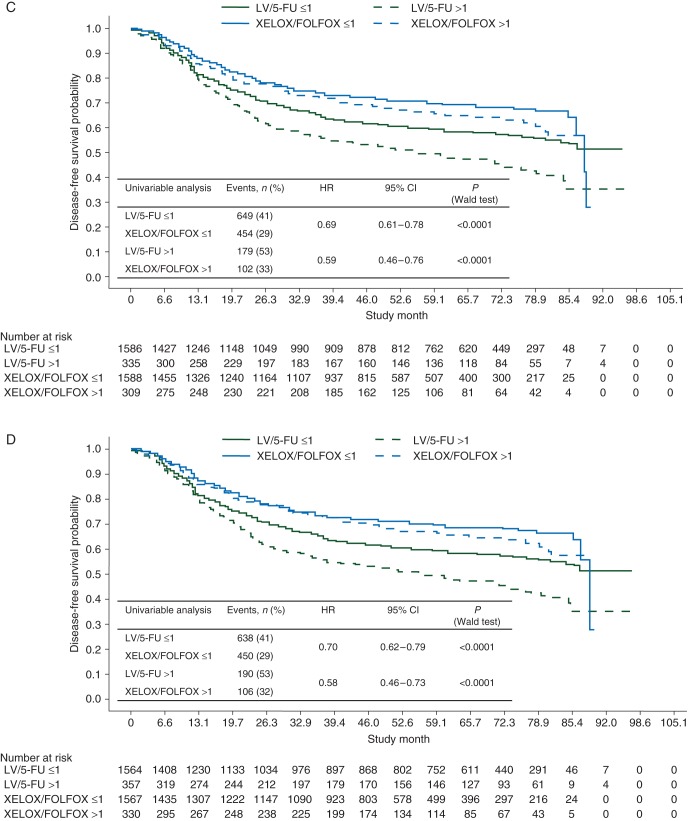

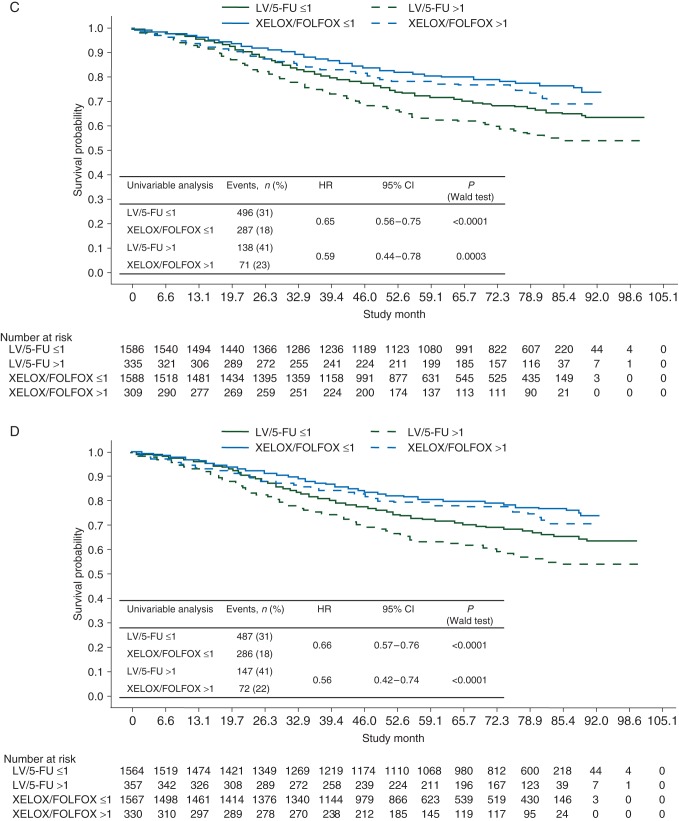

OS results were in line with DFS results (Figure 2). The HRs of XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU in patients with ≤12 and >12 lymph nodes examined were 0.76 (95% CI 0.61–0.94; P = 0.0122) and 0.72 (95% CI 0.59–0.88; P = 0.0017), respectively.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier plots of overall survival (A) for the intention-to-treat population, (B) by age (<70 versus ≥70 years), (C) by Charlson Comorbidity Index (≤1 versus >1), and (D) by National Cancer Institute Combined Index (≤1 versus >1). 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; FOLFOX, leucovorin, 5-fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin; LV, leucovorin; XELOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.

Multivariable analyses confirmed the unadjusted analyses (Table 2); however, age did not appear to impact the DFS benefit when MC was adjusted for in the same model, while age appeared to impact OS regardless of adjustment.

Table 2.

Multivariable efficacy analyses

| Effect/covariable | Disease-free survival |

Overall survival |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| Model not including CCI or NCI | ||||||

| Randomized treatment | ||||||

| XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU | 0.68 | 0.61–0.75 | <0.0001 | 0.64 | 0.57–0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (female versus male) | 0.86 | 0.78–0.95 | 0.0022 | 0.85 | 0.76–0.96 | 0.0081 |

| Age (<70 versus ≥70 years) | 0.89 | 0.79–1.00 | 0.0465 | 0.73 | 0.64–0.84 | <0.0001 |

| T stage (T1–2 versus T3–4) | 0.53 | 0.44–0.65 | <0.001 | 0.53 | 0.42–0.68 | <0.0001 |

| N stage (N1 versus N2) | 0.55 | 0.50–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.44–0.56 | <0.0001 |

| Model including CCI | ||||||

| Randomized treatment | ||||||

| XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU | 0.66 | 0.59–0.73 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.55–0.71 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (female versus male) | 0.84 | 0.76–0.94 | 0.0020 | 0.85 | 0.75–0.96 | 0.0102 |

| Age (<70 versus ≥70 years) | 0.90 | 0.79–1.02 | 0.0983 | 0.77 | 0.66–0.89 | 0.0004 |

| T stage (T1–2 versus T3–4) | 0.57 | 0.46–0.71 | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.43–0.73 | <0.0001 |

| N stage (N1 versus N2) | 0.57 | 0.51–0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.51 | 0.45–0.57 | <0.0001 |

| CCI (≤1 versus >1) | 0.79 | 0.69–0.90 | 0.0004 | 0.76 | 0.65–0.89 | 0.0005 |

| Model including NCI (NSABP C-08 excluded) | ||||||

| Randomized treatment | ||||||

| XELOX/FOLFOX versus LV/5-FU | 0.66 | 0.59–0.73 | <0.0001 | 0.62 | 0.55–0.71 | <0.0001 |

| Gender (female versus male) | 0.85 | 0.76–0.94 | 0.0021 | 0.85 | 0.75–0.96 | 0.0108 |

| Age (<70 versus ≥70 years) | 0.90 | 0.79–1.02 | 0.1024 | 0.77 | 0.66–0.89 | 0.0004 |

| T stage (T1–2 versus T3–4) | 0.57 | 0.46–0.71 | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.43–0.73 | <0.0001 |

| N stage (N1 versus N2) | 0.57 | 0.51–0.63 | <0.0001 | 0.50 | 0.44–0.57 | <0.0001 |

| NCI (≤1 versus >1) | 0.80 | 0.70–0.91 | 0.0006 | 0.77 | 0.66–0.90 | 0.0007 |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI, confidence interval; FOLFOX, leucovorin, fluorouracil plus oxaliplatin; LV/5-FU, leucovorin/5-fluorouracil; NCI, National Cancer Institute Combined Index; NSABP, National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project; XELOX, capecitabine plus oxaliplatin.

As the HRs for DFS and OS were consistent regardless of the number of lymph nodes examined, this variable was not included in the multivariable model.

No significant oxaliplatin-by-age interaction was found (supplementary Table S2). A numerical trend for an interaction with oxaliplatin was exhibited for NCI. In comparison with patients not receiving oxaliplatin, patients aged <70 and receiving oxaliplatin did not gain an additional benefit compared to those 185 patients aged ≥70 and receiving oxaliplatin. Likewise, patients with a CCI/NCI score ≤1 and receiving oxaliplatin did not gain an additional benefit compared to those with a CCI/NCI score >1 and receiving oxaliplatin.

Analyses were repeated in the entire stage III cohorts, adjusting for bevacizumab use, and showed similar results: DFS HR 0.68 (95% CI 0.63–0.74; P < 0.0001), OS HR 0.65 (95% CI 0.58–0.72; P < 0.0001).

safety

Grade 3/4 AEs of special interest for oxaliplatin therapy are shown in Table 3. Rates were similar, overall, between CCI score and age subgroups.

Table 3.

Grade 3/4 adverse events of special interest to oxaliplatin therapy

| Adverse event, n (%) | Charlson Comorbidity Index score |

Age |

Treatment |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1 |

>1 |

<70 |

≥70 |

|||||||

| LV/5-FU (n = 1567) | Ox (n = 1567) | LV/5-FU (n = 331) | Ox (n = 305) | LV/5-FU (n = 1479) | Ox (n = 2390) | LV/5-FU (n = 419) | Ox (n = 477) | LV/5-FU (n = 1898) | Ox (n = 2867) | |

| All | 522 (33) | 845 (54) | 93 (28) | 170 (56) | 470 (32) | 1233 (52) | 145 (35) | 283 (59) | 615 (32) | 1516 (53) |

| Neutropenia | 171 (11) | 418 (27) | 24 (7) | 75 (25) | 147 (10) | 655 (27) | 48 (11) | 143 (30) | 195 (10) | 798 (28) |

| Diarrhea | 244 (16) | 229 (15) | 47 (14) | 50 (16) | 223 (15) | 270 (11) | 68 (16) | 95 (20) | 291 (15) | 365 (13) |

| Neuropathy | 1 (<1) | 225 (14) | 0 (0) | 51 (17) | 1 (<1) | 336 (14) | 0 (0) | 70 (15) | 1 (<1) | 396 (14) |

| Vomiting/nausea | 78 (5) | 120 (8) | 19 (6) | 24 (8) | 77 (5) | 161 (7) | 20 (5) | 52 (11) | 97 (5) | 213 (7) |

| Stomatitis, all | 85 (5) | 13 (<1) | 19 (6) | 2 (<1) | 79 (5) | 25 (1) | 25 (6) | 6 (1) | 104 (5) | 31 (1) |

| Hand–foot syndrome | 9 (<1) | 44 (3) | 2 (<1) | 13 (4) | 10 (<1) | 60 (3) | 1 (<1) | 10 (2) | 11 (<1) | 70 (2) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 47 (3) | 21 (1) | 6 (2) | 1 (<1) | 40 (3) | 26 (1) | 13 (3) | 5 (1) | 53 (3) | 31 (1) |

| Neutropenic fever/sepsis | 8 (<1) | 7 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 2 (<1) | 8 (<1) | 6 (<1) | 3 (<1) | 5 (1) | 11 (<1) | 11 (<1) |

| Serious adverse event, n (%) | ||||||||||

| All | 263 (17) | 304 (19) | 72 (22) | 69 (23) | 229 (16) | 319 (13) | 106 (25) | 116 (24) | 335 (18) | 435 (15) |

Patients may have experienced ≥1 adverse event.

LV/5-FU, leucovorin/5-fluorouracil; Ox, oxaliplatin-containing therapy, i.e. capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) or LV/5-FU plus oxaliplatin (FOLFOX).

There were fewer serious grade 3/4 AEs in patients aged <70, as expected; however, the incidences were similar when comparing regimens across cohorts.

discussion

Oxaliplatin plus capecitabine or LV/5-FU provided a significant benefit in the adjuvant treatment of stage III CC independent of age or MC. The benefit was modestly attenuated in patients aged ≥70 (similar results were found when comparing age <65 and ≥65 subgroups; data not shown). The safety profiles of XELOX/FOLFOX and LV/5-FU are similar in this setting, although patients ≥70 experienced a higher proportion of serious grade 3/4 AEs with XELOX/FOLFOX. However, the primary safety concern with oxaliplatin is neuropathy, and we showed that its incidence at grade 3/4 was not related to advancing age or MC.

The finding that the oxaliplatin benefit is maintained regardless of age is in agreement with XELOXA [3, 9], although the DFS benefit was greater in our analysis (HR in the ≥70 subgroup: 0.77 versus 0.87 in XELOXA).

Current data somewhat conflict with the initial 2009 ACCENT analysis (which did not include MC as a cofactor) [8], and NSABP C-07 [5] in which a significant age–treatment interaction was observed. The updated 2013 ACCENT analysis, which included limited individual patient data from XELOXA, reported results similar to ours, i.e. diminished DFS with oxaliplatin-based therapies in patients ≥70, with no apparent age–treatment interaction [18]. This suggests a DFS and time to recurrence (TTR) benefit for a selected subgroup of patients, particularly when the analysis was restricted to patients with stage III disease (aligned with the current observations). However, the updated ACCENT analysis did not report a significant DFS or TTR benefit of oxaliplatin-based therapy in patients ≥70, and there was a borderline significant detrimental effect on OS. By contrast, in the current analysis, a significant benefit was observed for DFS and OS in both age cohorts when adjusted for MC (although this was diminished in patients ≥70). As noted by the ACCENT authors, the results are likely to be partially related to competing causes of mortality present in older patients. They acknowledged that they did not investigate the potential impact of MC on outcomes. An independent effect of MC on treatment benefit associated with oxaliplatin-based therapies was not observed in the presented analysis. Exclusion of NSABP C-07 may also account for differing results. The rarely used FLOX regimen, evaluated in NSABP C-07, did not provide an OS benefit and was associated with a significant age–treatment interaction where patients ≥70 had worse survival versus LV/5-FU. FLOX was also associated with higher rates of severe toxicity and patients were likely to discontinue oxaliplatin early. Consequently, FLOX is not commonly used. Current analyses may be more reflective of current clinical practice as FOLFOX and XELOX are preferred regimens [6, 7].

As confirmed by recent ‘real-world’ data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry linked to Medicare claims (SEER-Medicare), the New York State Cancer Registry linked to Medicaid and Medicare claims (NYSCR), the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Outcomes Database, and the Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS), adding oxaliplatin is beneficial across diverse practice settings for patients ≥75 and <75 reported in separate analyses [19, 20], although the benefit was attenuated in patients >75 [20]. These observations are supported here. Distributions of CCI scores were also similar between these general stage III CC population cohorts (CCI ≤1: 83%–94% and 76%–89%, respectively) and in the current dataset (83%–84%). In the overall general population, 92% had a CCI score of ≤1 compared with 83% in the current dataset. Therefore, the presented findings suggest that oxaliplatin benefit is applicable to the general population of patients with stage III CC fit enough to receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

Results should be viewed with the limitations of the original data sources. There was an imbalance in the duration of follow-up and comorbidity information was not available for patients enrolled onto NSABP C-08. A narrow distribution of comorbidity scores was observed within the pool (reflecting the elderly who enter trials), although scores were consistent with those observed in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy in routine practice [19, 20]. Medical frailty was not assessed, which is a different entity from MC [21] and may be more directly associated with age. There were also a limited number of patients over the age of 75 and a low number of events to allow meaningful analyses of this subgroup. Finally, the impact of infusional versus bolus 5-FU could not be addressed directly, although data from GERCOR C96.1 showed no significant difference between these regimens in the adjuvant setting [22].

Results further support consideration of XELOX or FOLFOX as standard treatment options for the adjuvant management of stage III CC in all age groups and in patients with comorbidities, consistent with those who were eligible for these clinical trials. Indeed, recent ACCENT data suggested that among patients with CC on clinical trials who survive up to 5 years, their 3-year survival remains poorer than a matched general population [23]. But patients who received oxaliplatin, had stage II disease, remained recurrence-free, or were aged >70 years achieved similar survival rates (within 5%) to their matched peers, which should be the goal of any medical therapy [23].

funding

Genentech, Inc., funded this analysis; The NCI/NSABP designed NSABP C-08. NSABP C-08 was supported by: Public Health Service grants (U10 CA 12027, U10 CA 69651, U10-CA-37377, and U10 CA-69974) from the National Cancer Institute, Department of Health and Human Services, Sanofi-Synthelabo, Inc., and Genentech, Inc. Chugai and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd/Genentech, Inc., funded and designed AVANT. F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd funded and designed X-ACT and XELOXA.

disclosure

DGH has served as a consultant/advisor for Genentech, Inc. TCH has served as a consultant/advisor for F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. CJT has received honoraria from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd/Genentech, Inc. EFMcK is an employee of, and has stocks/stock options in, Genentech, Inc. MWS has received speaker bureau honoraria from Genentech, Inc., Sanofi-Aventis, Amgen, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. SL is an employee of Genentech, Inc. H-JS has attended advisory boards for F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi-Aventis, and Astellas, has lectured for F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, Sanofi-Aventis, and Merck AG, and has received research funding from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and Merck AG. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

Support for third-party writing assistance for this manuscript, furnished by Daniel Clyde, PhD, was provided by Genentech, Inc.

references

- 1.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 350: 2343–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3109–3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haller DG, Tabernero J, Maroun J, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin compared with fluorouracil and folinic acid as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 1465–1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmoll H-J, Tabernero J, Maroun JA, et al. Capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (XELOX) versus bolus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (5-FU/LV) as adjuvant therapy for stage III colon cancer: survival follow-up of study NO16968 (XELOXA). J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: Abstr 338. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, Allegra CJ, et al. Oxaliplatin as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: updated results of NSABP C-07 trial, including survival and subset analyses. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 3768–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer. V3.2012 2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Van Cutsem E, Oliveira J. Primary colon cancer: ESMO clinical recommendations for diagnosis, adjuvant treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2009; 20(suppl): iv49–iv50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jackson McCleary NA, Meyerhardt J, Green E, et al. Impact of older age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in >12500 patients (pts) with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT Database. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: Abstr 4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller DG, Cassidy J, Tabernero J, et al. Efficacy findings from a randomized phase III trial of capecitabine plus oxaliplatin versus bolus 5-FU/LV for stage III colon cancer (NO16968): no impact of age on disease-free survival (DFS). American Society of Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (Abstr 284), Orlando , FL, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, et al. Comorbidity and age as predictors of risk for early mortality of male and female colon carcinoma patients: a population-based study. Cancer 1998; 82: 2123–2134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hines RB, Chatla C, Bumpers HL, et al. Predictive capacity of three comorbidity indices in estimating mortality after surgery for colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 4339–4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP, et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 352: 2696–2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Gramont E, Van Cutsem E, Schmoll HJ, et al. Bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer (AVANT): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13: 1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, et al. Initial safety report of NSABP C-08: a randomized phase III study of modified FOLFOX6 with or without bevacizumab for the adjuvant treatment of patients with stage II or III colon cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3385–3390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O'Connell MJ, et al. Phase III trial assessing bevacizumab in stages II and III carcinoma of the colon: results of NSABP protocol C-08. J Clin Oncol 2011; 29: 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edge S, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmoll HJ, Twelves C, Sun W, et al. Effect of adjuvant capecitabine or fluorouracil, with or without oxaliplatin, on survival outcomes in stage III colon cancer and the effect of oxaliplatin on post-relapse survival: a pooled analysis of individual patient data from four randomised controlled trials. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 1481–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCleary NJ, Meyerhardt JA, Green E, et al. Impact of age on the efficacy of newer adjuvant therapies in patients with stage II/III colon cancer: findings from the ACCENT database. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 2600–2606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Martin CF, et al. Comparative effectiveness of oxaliplatin vs non-oxaliplatin-containing adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 211–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanoff HK, Carpenter WR, Stürmer T, et al. Effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on survival of patients with stage III colon cancer diagnosed after age 75 years. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 2624–2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, et al. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004; 59: 255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.André T, Quinaux E, Louvet C, et al. Phase III study comparing a semimonthly with a monthly regimen of fluorouracil and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for stage II and III colon cancer patients: final results of GERCOR C96.1. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 3732–3738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renfro LA, Grothey A, Kerr DJ, et al. Survival following stage II/III colon cancer (CC): accent-based comparison versus matched general population (MGP). J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: Abstr 3601. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.