Abstract

Using Community-Based and tribal Participatory Research (CBPR/TPR) approaches, an academic-tribal partnership between the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute and the Suquamish and Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribes developed a culturally grounded social skills intervention to promote increased cultural belonging and prevent substance abuse among tribal youth. Participation in the intervention, which used the Canoe Journey as a metaphor for life, was associated with increased hope, optimism, and self-efficacy and with reduced substance use, as well as with higher levels of cultural identity and knowledge about alcohol and drugs among high school-age tribal youth. These results provide preliminary support for the intervention curricula in promoting positive youth development, an optimistic future orientation, and the reduction of substance use among Native youth.

INTRODUCTION

American Indian and Alaska Native (AI/AN) people demonstrate resilience, strength, and endurance despite centuries of postcolonial efforts to eradicate and assimilate them. Resulting health disparities and health inequality are critical issues for AI/AN tribes and communities. Comprising only 1.7% of the overall population, AI/ANs suffer alarming rates of health disparities, resulting in a life expectancy that is 4.2 years less than that of the U.S. all races population (Indian Health Service, 2015; Norris, Vines, & Hoeffel, 2012). A recent report from the Institute of Medicine (2012) stated that AI/ANs, as a group, saw the fewest advances toward achieving Healthy People 2010 objectives.

Among the disparities experienced by many AI/ANs is substance abuse and its related negative health and social consequences (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2010; Whitesell, Beals, Big Crow, Mitchell, & Novins, 2012), which has led the Indian Health Service to call alcohol and substance abuse the number-one health problem among AIs. Of particular concern is substance use and abuse among AI/AN youth. Older data indicate that alcohol and substance abuse by AI/AN youth in some communities has reached alarming rates (Beauvais, 1992). AI/AN youth also were found to begin alcohol/drug use at an earlier age, to have a higher frequency and quantity of consumption, and to have disproportionately higher levels of associated negative consequences (Beauvais, 1996; Hawkins, Cummins, & Marlatt, 2004; Moran & Reaman, 2002). More recent data indicate that, while past month alcohol use was similar between AI/AN youth and the national average (17.5% vs. 16.0%, respectively), AI/AN youth past month marijuana use (13.8% vs. 6%, respectively) and nonmedical use of prescription drugs such as opiate pain medication (6.1% vs. 3.3%, respectively) were nearly twice the national average (Beauvais, Jumper-Thurman, Helm, Plested, & Burnside, 2004; SAMHSA, 2011).

Given its prevalence, the prevention of substance abuse among AI/AN youth is critical to avoid associated negative consequences such as suicide, comorbid mental health disorders, school dropout, delinquency, reduced academic performance, diabetes, injuries, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder, poverty, cancer, and heart disease (Gray & Nye, 2001; Whitbeck, Johnson, Hoyt, & Walls, 2006; Whitbeck, Walls, & Welch, 2012). As such, developing interventions for the prevention and treatment of substance abuse is a high priority for most AI/AN communities, in particular because of the relatively young age of many AI/ANs—their median age is 29 years, versus 37.2 years for the population as a whole (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011).

More recently, there has been increased focus on the role of historical trauma as a contributing factor to substance abuse and mental health challenges among AI/ANs. Removal of AI/AN children to boarding schools, theft of land, disruption of culture, loss of language and traditional practices, and the resulting grief has been associated with increased vulnerability to mental health and substance abuse issues for AI/ANs (Brave Heart & DeBruyn, 1998; Duran, Duran, Brave Heart, & Yellow Horse-Davis, 1998; Struthers & Lowe, 2003; Walters & Simoni, 2002). However, there is increasing evidence that cultural identity (i.e., one’s sense of belonging to an ethnic group, defined by cultural heritage; shared values, traditions, and practices; and often language; Phinney & Ong, 2007), cultural continuity (i.e., the transmission of core cultural beliefs, values, and traditions across generations), and feeling connected to one’s tribe and community are important for preventing substance abuse, suicide, and other significant behavioral health issues, and that community-based and culturally grounded programs may be the most effective prevention strategy (Gone & Calf Looking, 2011; Hawkins et al., 2004; Lane & Simmons, 2011; Lowe, Liang, Riggs, & Henson, 2012; Moran & Reaman, 2002; Thomas, Donovan, & Sigo, 2010).

Addressing substance-related health disparities and health inequality in Indian Country is even more pressing given the lack of adequate, let alone effective and culturally appropriate, services available to AI/ANs (Gone & Trimble, 2012). Current services and evidence-based practices (EBPs), most of which have been developed with and for the majority population, are often viewed with distrust by AI/AN communities (Cross, Friesen, & Maher, 2007; Gone & Alcantara, 2007; Lane & Simmons, 2011; Larios, Wright, Jernstrom, Lebron, & Sorensen, 2011; Lowe, Riggs, & Henson, 2011; Wexler, 2011), and there is little evidence that they are effective for AI/ANs (Gone, 2007; Lowe et al, 2011; 2012). Many AI/AN communities have also come to view research with suspicion and mistrust (Christopher, Watts, McCormick, & Young, 2008; Lowe et al., 2011).

Community-based and Tribal Participatory Research (CBPR/TPR) approaches have begun to address this research gap, with AI/AN communities participating as collaborators and co-researchers in the identification of issues of concern, strengths to address these issues, and desired outcomes; the analysis and interpretation of data; and the effective dissemination of findings (Ball & Janyst, 2008; Baydala et al., 2009; Burhansstipanov, Christopher, & Schumacher, 2005; Christopher et al., 2008; 2011; Cochran et al., 2008; Fisher & Ball, 2003; 2005; Holkup, Tripp-Reimer, Salois, & Weinert, 2004; LaVeaux & Christopher, 2009; Michell, 2009; Thomas, Rosa, Forcehimes, & Donovan, 2011). Community-driven, culturally grounded prevention interventions, derived from the beliefs and values of a given tibe or culture, appear to be more acceptable and potentially more effective for AI/AN youth than EBPs developed with non-Native populations (Gone & Calf Looking, 2011; Hawkins et al., 2004; Lane & Simons, 2011; Lowe et al., 2012; Moran & Reaman, 2002; Nebelkopf et al., 2011; Okamoto, Helm, Pel, McClain, Hill, & Hayashida, 2014).

Therefore, it is critical that efforts to reduce substance use and prevent substance abuse with AI/AN youth be implemented in partnership with AI/AN communities, incorporate local expertise and knowledge, build on strengths and resources within the communities, and integrate unique cultural practices (Brown, Baldwin, & Walsh, 2012). It is also important to recognize that the unique cultural characteristics and traditions of the more than 560 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. may limit the generalizability of interventions across tribes, requiring community-informed and tribal-specific adaptations (Gone & Trimble, 2012; Trimble & Beauvais, 2001; Whitesell, Kaufman, et al., 2012).

In this article, we describe the CBPR/TPR process involved in a university-tribal partnership that led to the development of a community-informed, culturally grounded intervention to promote a sense of cultural belonging and to prevent substance abuse among tribal youth. The transfer of the process to a second tribal community, to demonstrate replicability of the development and adaptation process and generalizability of the intervention, is also described. Finally, we present the results of an initial evaluation of the intervention’s impact.

THE HEALING OF THE CANOE PROJECT

CBPR/TPR Process and Intervention Development

The Healing of the Canoe project (HOC; http://healingofthecanoe.org) is a collaboration among the Suquamish Tribe, the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, and the University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute (ADAI). Both tribes have given their permission to be named in this article, and both are sovereign, reservation-based tribes in the Pacific Northwest with enrollments of approximately 1,100 and 1,200, respectively (although fewer than half of the enrolled members live on each reservation).

The collaborative partnership was initiated by the Suquamish Tribe, when the Director of its Wellness Program approached ADAI asking if it would be possible to work together to address the community’s increasing concern about alcohol and drug use among its youth. Members of the ADAI research staff, one of whom is AN, began meeting regularly with the Wellness Program staff, tribal leaders and Elders, and the Suquamish Cultural Co-Operative (the body designated by the Tribal Council to ensure that all programs introduced into the community are consistent with tribal sovereignty, culture, and values).

Concurrent with this initial development work, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) issued a call for applications focusing on the use of CBPR approaches to address health disparities. The Suquamish Tribe and ADAI researchers jointly decided to apply for a grant to support the development of a culturally grounded substance abuse prevention program. Consistent with principles of CBPR and TPR, tribal- and university-based personnel shared responsibility in a variety of areas, including the grant application process, the proposed project leadership, and the research team membership. We were fortunate to have been selected as one of 25 grantees funded as part of NIMHD’s CBPR initiative. The HOC team worked with community members to develop an intervention that blends cognitive-behavioral life skills with culturally grounded, tribal-specific teachings, practices, and values that targeted both the prevention of substance use/abuse and the promotion of cultural identity and belonging among tribal youth.

This article focuses on the first two phases of the project. Phase I involved partnership development, needs and resources assessment, intervention development, and feasibility piloting with the Suquamish Tribe (Lonczak et al., 2013; Thomas et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2009). Phase II extended the partnership to the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe to replicate the development process, and involved an evaluation of the intervention in the two communities.

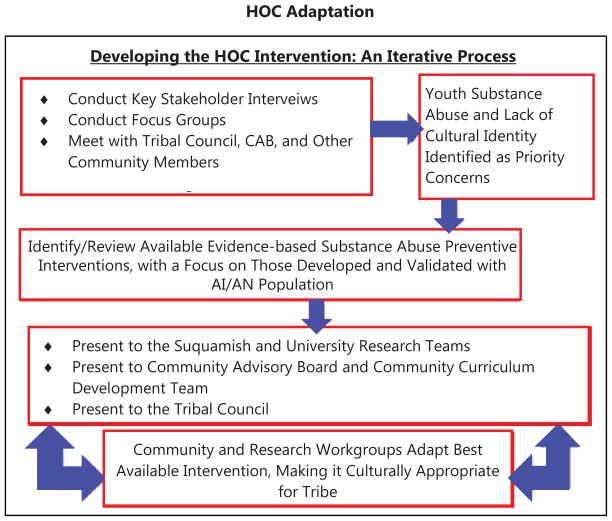

Figure 1 provides a relational mapping of the different organizations, both tribal and university, and the research teams involved in the HOC project across its first two phases.

Figure 1.

Developed by Qualitative Research Team, Research for Improved Health Study, Center for Participatory Research, University of New Mexico, 2013; used with permission

METHODS

Tribal and University Review

Procedures for all phases of the research were reviewed and approved by each tribe’s Community Advisory Board (CAB) and Tribal Council.

Before Phase I project activities began, the Suquamish Tribal Council passed a resolution to permit the research to proceed, and both the Tribe and the University of Washington developed, negotiated, and accepted a memorandum of understanding and a data ownership, sharing, and dissemination ageement. The University of Washington Human Subjects Division also reviewed and approved all activities for the ethical conduct of research. To partcipate in the research, youth provided assent and their parents/guardians provided consent.

HOC: Phase I

Phase I was a 3-year planning and development period (June 2005-June2008). The NIMHD grant guidelines specified that, during this phase, a CBPR approach would be used to (1) establish a university-community working partnership, with a focus on community engagement, (2) conduct a community needs and resources assessment, (3) identify and prioritize health disparities, (4) specify a disorder to address through CBPR development of appropriate intervention(s), and (5) develop and pilot community-based intervention(s).

Needs and Resources Assessment with the Suquamish Tribe

Consistent with these expectations, the ADAI and Suquamish research team used CBPR/TPR approaches to engage the community and conduct a community readiness, needs, and resources assessment. Guided by the Cultural Co-Operative, which serves as the project’s CAB in Suquamish, tribal research team members conducted interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with service providers, Elders, youth, and other community members (Thomas et al., 2009; Thomas et al., 2010). The team used a modification of the community readiness assessment developed by the Colorado State University Tri-Ethnic Research Center (Jumper-Thurman, Plested, Edwards, Foley, & Burnside, 2004).

Two primary concerns emerged from the community assessment: (1) prevention of youth substance abuse and (2) the importance of cultural identity, meaning, and tribal/community belonging among youth. The community viewed substance abuse as being directly related to the lack of cultural connectedness among the youth. The greatest resources in the community to deal with these issues were identified as tribal Elders; tribal youth; and Suquamish tribal traditions, values, beliefs, teachings, practices and stories. Given these findings and context, the key stakeholders, focus group members, and CAB members felt that the community concern about youth substance abuse should be addressed using a process that strengthened youths’ connection to their tribe and community, especially to extended family; specific mentors; and cultural activities, traditions, and values, all of which are believed to promote cultural identity (Caldwell et al., 2005; Edwards, 2003; Schweigman, Soto, Wright, & Unger, 2011). In addition, it would be important to build community connections, increase community support systems, and promote culture. These are all key components and core competencies of positive youth development and have been incorporated into other culturally grounded, community-informed approaches to minimize the risk of substance abuse and mental health problems and to promote wellness among AI/AN and other ethnic minority youth (Cross et al., 2011; Haegerich & Tolan, 2008; Hawkins et al., 2004; Kenyon & Hanson, 2012; Lam, Lau, Law, & Poon, 2011; Lowe et al., 2012; Smokowski, Evans, Cotter, & Webber, 2014).

Intervention Development and Piloting with the Suquamish Tribe

Both tribal- and university-based team members gathered information about EBPs and promising prevention interventions that could be adapted to meet the identified needs. The Canoe Journey/Life’s Journey curriculum (Hawkins & La Marr, 2012; LaMarr & Marlatt, 2005; Marlatt et al., 2003), developed by University of Washington colleagues and the Seattle Indian Health Board for use with inter-tribal urban AI/AN youth, was selected as a model. It is an 8-session curriculum designed to help urban Native youth identify and utilize healthy and appropriate social, interpersonal, and intrapersonal life skills and lifestyle choices to prevent the initiation of substance use, promote abstinence, and reduce the risk of harm and the potential for developing an addiction. The curriculum, which was designed to be adaptable to other communities, is culturally grounded. It is based on the Canoe Journey, a major factor in cultural revitalization among Pacific Northwest coastal tribes (Hawkins & La Marr, 2012; Johnson, 2012; Lane & Simmons, 2011; Neel, 1995). The seagoing canoe represents the traditional means of transportation, commerce/trade, fishing, and social gathering among Pacific Northwest tribes. The modern-day Canoe Journey, which began in 1989 with the “Paddle to Seattle” from Suquamish, has become an annual event, often drawing over 100 canoes. The journey includes stops at tribal communities along the way to dance, drum, sing, and share stories until arriving at a final hosting community, where there is a weeklong potlatch or celebration. The journey honors ancestors, embraces Indigenous values and traditions, and “teaches the community traditional cultural ways of being” (Hawkins & La Marr, 2012, p. 238). As an alcohol-and drug-free event, the journey also offers participants an opportunity for “healing and recovery of culture, traditional knowledge, and spirituality” (Washington Indian Gaming Association, 2014).

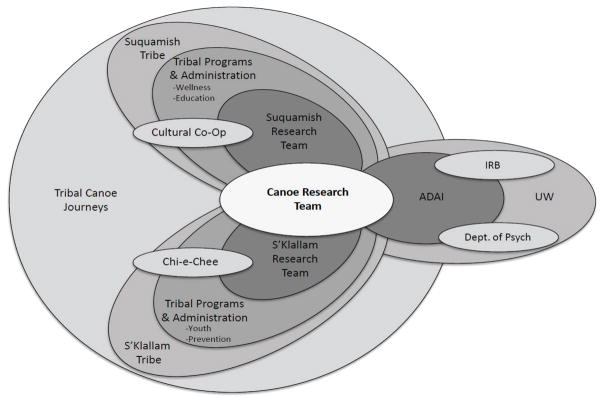

A community-based curriculum review and development group, composed of Elders, CAB members, and other community members, and facilitated by Suquamish and ADAI research team members, used principles for cultural adaptation of prevention interventions (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004) and an iterative process (Chu, Huynh, & Area’n, 2012) to adapt the original Canoe Journey/Life’s Journey curriculum to be specific to the Suquamish Tribe. The iterative process followed principles of cultural adaptation––namely, initial gathering of information about available and relevant evidence-based prevention interventions; preliminary adaptation through a back-and-forth review of information and recommended adaptations among the research teams, the Cultural Co-Operative, the curriculum development team, and the Tribal Council; preliminary adaptation pilot testing; and modification and refinement (Barrera & Castro, 2006; Chu, Huynh, & Area’n, 2012). The goal of this iterative adaptation process, depicted in Figure 2, was to preserve core evidence-based treatment components of the prevention intervention while adding cultural content to enhance tribal-specific cultural relevance (Castro, Barrera, & Martinez, 2004).

Figure 2.

HOC Adaptation

Holding Up Our Youth consists of an 11-session curriculum, attempting to prevent initiation of substance use among those not yet using and escalation among those who already have initiated use. The curriculum is culturally grounded and uses the Canoe Journey as a metaphor and teaching tool to provide Native youth the skills needed to navigate through life’s journey without being pulled off course by alcohol or drugs. It blends tribal traditions, cultural values, and Indigenous knowledge with evidence-based practices and elements of positive youth development. It includes an Honoring Ceremony in which participants are honored for their unique strengths and accomplishments. The youth, in turn, honor their mentors and important role models in oral testimony and with traditional gifts that they have made during the program. The sessions are listed in Table 1 below, and more detailed descriptions can be found at http://healingofthecanoe.org/holding-up-our-youth/. Prior to the implementation described below, we pilot tested the curriculum with Suquamish middle school and junior high school students in a tribal summer session and as an after-school program; the results (unpublished) demonstrated that the program was feasible to conduct and acceptable to youth.

Table 1.

Sessions Included in the Holding Up Our Youth Curriculum

| Session Title | Session Goals/Focus* |

|---|---|

| 1. The Four Winds/Canoe Journey as a Metaphor |

|

| 2. How am I Perceived? Media Awareness and Literacy |

|

| 3. Who am I? Beginning at the Center |

|

| 4. Community Help and Support: Help on the Journey |

|

| 5. Who Will I Become? Goal Setting |

|

| 6. Overcoming Obstacles: Solving Problems |

|

| 7. Listening |

|

| 8. Effective Communication: Expressing Thoughts and Feelings |

|

| 9. Moods and Coping with Negative Emotions |

|

| 10. Safe Journey without Alcohol/Drugs |

|

| 11. Strengthening our Community |

|

| 12. Honoring Ceremony |

|

Traditional stories, cultural activities and speakers from the community are woven throughout the sessions.

At the end of Phase I, we also asked a Native researcher with expertise in CBPR to conduct an external evaluation of the project (Randall, 2008). Qualitative data were derived from interviews with key stakeholders and focus groups with community members to assess the community engagement and curriculum development processes, as well as initial impressions of the curriculum as delivered in the pilot feasibility implementations.

HOC: Phase II

The primary aims of Phase II (July 2008-February 2013) were: (1) using CBPR methods, to work with the Suquamish Tribe to refine, implement, and evaluate the intervention developed in Phase I; and (2) to replicate the CBPR and curriculum development process with the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe (PGST) to tailor the curriculum to PGST’s traditions and culture, and to implement and evaluate the intervention in both communities.

Intervention Implementation with the Suquamish Tribe

Working with tribal communities and using a CBPR/TPR approach are not always linear processes (Lowe et al., 2011), and researchers need to be responsive and adapt to changes in the community over the course of a study. Although the initial curriculum had been developed for and piloted with middle school students, at the beginning of Phase II the Suquamish CAB wanted to shift the focus of the intervention to high school students, to coincide with the opening of a tribal high school. They invited the HOC team to teach the Holding Up Our Youth curriculum in the new high school. This shift required us to change the curriculum content slightly to be more age appropriate; in addition, it was expanded from the original 11 sessions to a year-long academic class, which met daily for 1.5 hours. The class included a mix of lectures, discussion, dialogue, multimedia, student presentations, and group activities. Guest speakers were invited as often as possible to increase the breadth and depth of exposure to Suquamish culture and traditional activities. The class was facilitated by one female and one male staff who were members of the Suquamish Tribe and research team, which was most effective with a mixed gender group. Students were able to receive class credit from both the high school and a local community college. However, after 1 year the high school closed to review and revise its overall focus and instructional approach and curriculum; thus, it was not possible to implement the intervention for a second year.

Intervention Extension to PGST

An important aspect of the Holding Up Our Youth curriculum is that, while it standardizes the core social, interpersonal, and intrapersonal skills to be delivered, it was designed to be adaptable: It has “placeholders” where other tribes/communities can insert their unique traditions, stories, values, and cultural practices. This format facilitates subsequent generalizability, dissemination, adaptation, and implementation by other tribes, and honors and protects tribal-specific cultural knowledge, which research suggests is important (Lane & Simmons, 2011; Moran & Reaman, 2002). As noted, a goal for Phase II was to replicate the CBPR community engagement and curriculum development processes with PGST. Therefore, concurrent with the implementation of the curriculum in the Suquamish high school, we began working with PGST. The transport of these processes to PGST was of particular interest because, despite their geographic proximity (10 miles by car, but 29 miles by canoe) and the fact that both are waterside communities actively involved in the Canoe Journey, Suquamish and PGST are quite different with respect to the nature of their reservations (e.g., their languages are different, and one reservation is “checker boarded,” with much of the land having been sold to non-tribal members, while the other is consolidated, with almost all of the land owned by tribal members). These differences provided an opportunity to determine the portability and generalizability of the processes, and our ability to tailor the curriculum to another tribal culture.

The PGST Tribal Council approved involvement in the project through a tribal resolution; a memorandum of understanding; and a data ownership, sharing, and dissemination agreement. The PGST research team, composed of tribal members, was guided by its CAB, the Chi-e-chee Network, which is the tribe’s Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Drugs Prevention Committee. One of the Chi-e-chee Network’s duties is to assure that all prevention projects performed by different tribal departments are culturally competent and respectful of the sovereignty and integrity of the PGST culture and traditions. Working in collaboration with the Suquamish and ADAI teams and the Chi-e-chee Network, the PGST research team conducted community readiness, needs, and resources assessments using focus groups and key stakeholder interviews. The community identified the prevention of youth substance abuse and cultural revitalization as the issues it wished to address with the curriculum.

To further adapt the Holding Up Our Youth curriculum, members of the ADAI and PGST research teams met over a number of months with a tribal curriculum revision and adaptation committee, composed of PGST Elders, Chi-e-chee members, and other community members. During this process, the PGST research team engaged the community through newsletters, community meetings, and regular reports to Chi-e-chee and the Tribal Council. The result was an adaptation that incorporated Port Gamble S’Klallam culture, traditions, values, and stories into the placeholders throughout the curriculum template, while retaining the core social skills elements and evidencebased components. It is entitled Navigating Life the S’Klallam Way. Session content parallels that found in the Holding Up Our Youth, except for the tribal-specific material and a slight reordering of the sessions. The sessions are listed in Table 2 on the next page, and more detailed descriptions can be found at http://healingofthecanoe.org/navigating-life-the-sklallam-way/.

Table 2.

Sessions Included in the Navigating Life the S’Klallam Way curriculum

| Session Title | Session Goals/Focus* |

|---|---|

| 1. The Four Seasons/Canoe Journey as a Metaphor |

|

| 2. Who am I? Beginning at the Center |

|

| 3. How am I Perceived? Media Awareness and Literacy |

|

| 4. Community Help and Support: Help on the Journey |

|

| 5. Moods and Coping with Negative Emotions |

|

| 6. Who Will I Become? Goal Setting |

|

| 7. Overcoming Obstacles: Solving Problems |

|

| 8. Listening |

|

| 9. Effective Communication: Expressing Thoughts and Feelings |

|

| 10. Safe Journey without Alcohol/Drugs |

|

| 11. Strengthening our Community |

|

| 12. Honoring Ceremony |

|

Traditional stories, cultural activities and speakers from the community are woven throughout the sessions.

Workshop Implementation of Intervention with Suquamish and PGST

The Suquamish team needed to develop an alternative method of delivering the curriculum following the closing of the high school; the PGST team also needed a delivery method for its newly developed curriculum. The two tribal research teams worked together to determine a format that would meet each community’s needs; a series of multiday intensive workshops to be held overnight in off-reservation retreat settings was chosen. Each team developed a series of three 2.5- to 3-day tribal-specific workshops spread over a 3-month period. Workshops for Suquamish youth used the Holding Up Our Youth curriculum, while those for PGST youth used the Navigating Life the S’Klallam Way curriculum. This new format and timeframe required yet another adaptation, but still incorporated the core elements from each of the lengthier curricula from which they were derived. The workshops were facilitated by research team staff who were members of the respective tribal communities; two of the facilitators (one from Suquamish and one from PGST) also were skippers of youth canoes involved in the annual Canoe Journey. In addition, mentors, Elders, and other community members participated as guest speakers or instructors in cultural practices. Students were given permission to miss their regular public school classes to attend the workshops.

Participants

Suquamish High School

All Suquamish high school students had the opportunity to participate in the Holding Up Our Youth intervention as part of their regular high school curriculum, and to receive high school or college credit for it, regardless of whether they opted to participate in the research component (e.g., completing assessments). While a larger number of students participated in the class across the academic year, only those for whom assent and parental consent were obtained are included here. The high school sample consisted of 8 students. There were 5 males and 3 females; 2 students were in the 10th grade and 6 were in the 12th grade. This cohort represented one-third of total student body, which fluctuated between 25–30 students during the school’s first year of operation.

Suquamish/PGST Workshops

Participants were recruited through community announcements about the workshops in monthly tribal newsletters, social networks (e.g., Facebook), fliers in youth programs (e.g., Sports and Recreation Department, Youth Council, Youth Center, Cultural Activity Workshops, Song and Dance Group, Youth Canoe Club), and personal contact. A total of 23 youth (5 males, 8 females in Suquamish; 3 males, 7 females in PGST) in 9th through 12th grade participated in the workshops. No incentives were provided for participating in the workshops.

Measures

Four target outcomes were evaluated using the same instruments in both the high school and workshop samples: (1) cultural identification and participation in cultural activities, (2) hope/optimism/self-efficacy, (3) knowledge about substance abuse, and (4) substance use. These variables were chosen by the ADAI and both tribal research teams because they represented domains that were primary targets of the intervention.

Cultural Identification and Participation in Cultural Activities

The measure of cultural identification was adapted by the research teams from measures of AI/AN identity (e.g., Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure; Phinney, 1992; Phinney & Ong, 2007), enculturation (e.g., American Indian Enculturation Scale; Winterowd, Montgomery, Stumblingbear, Harless, & Hicks, 2008; Zimmerman, Ramirez-Valles, Washienko, Walter, & Dyer, 1996, and cultural practices (e.g., Traditional Activities Scale; Stone, Whitbeck, Chen, Johnson, & Olson, 2006;). It consisted of nine items, each rated on a 4-point Likert sale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 4 (Strongly agree). We also asked youth how often they participated in a number of traditional Native cultural activities (e.g., singing/drumming, dancing, canoe pulling, fishing) on a scale from 1 (Never) to 5 (At least once per week).

Hope/Optimism/Self-efficacy

The Children’s Hope Scale (Snyder et al., 1997), known as the Questions about Your Goals Questionnaire when used with older youth, was used to assess hope, optimism, and positive expectations about the future. The six items, rated on a 6-point scale from 1 (None of the time) to 6 (All of the time), assess two components of hope/optimism: agency (e.g., the perception that one can initiate and sustain action toward a desired goal) and pathways (e.g., perceived capability to produce routes to those goals). The scale, which has demonstrated a high degree of internal consistency in use with AI/AN youth (Gowen, Bandurraga, Jivanjee, Cross, & Friesen, 2012), has been found to be related positively to self-esteem; self-efficacy; community, cultural, and individual resilience; community mindedness; conflict management; and coping, which are components of positive youth development (Cross et al., 2011; Gowen et al., 2012; Haegerich & Tolan, 2008; Snyder, 2000; Snyder et al., 1997; Sun & Shek, 2012).

Substance Use

Substance use was assessed with items from the Washington State Healthy Youth Survey (Washington State Department of Health, 2012), a measure of substance-related health risk behaviors that contribute to morbidity, mortality, and social problems among youth in Washington State. These behaviors include frequency of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use; behaviors that result in unintentional and intentional injuries (e.g., violence); and related risk and protective factors (e.g., community, school, peer and individual, family). This survey is typically administered every 2 years in 6th, 8th, 10th, and 12th grades in local school districts, and is used for local and state prevention program planning.

Substance Abuse Knowledge

The knowledge test consisted of 21 true/false items that assessed factual information about tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs of abuse (e.g., “Teenagers are too young to get addicted to alcohol or drugs,” “It takes the same amount of beer and wine to get a person drunk,” “Pain medications are safe to use even if you don’t have a prescription since they are legal drugs”). The items, developed by the ADAI research team, were based on information derived from the NIDA for Teens Drug Facts (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2011) and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Fact Sheets (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, n.d.).

Assessment Administration Schedule

These measures were administered to the high school sample at baseline (beginning of the school year), at the end of the school year (approximately 9 months after baseline), and at a follow-up assessment 4 months after the end of school. The measures were administered to the tribal-specific workshop participants at baseline (prior to the first workshop), following the last workshop (about 3 months following baseline), and at a 4-month follow-up assessment.

In addition, as part of the post-intervention assessment (at the end of the school year or at the end of the third workshop) participants responded to open-ended questions to provide qualitative feedback and their impressions of the intervention (e.g., “How would you describe your overall experience with the HOC class?” “What was your favorite/least favorite part?” “What part[s] do you think had the most positive impact on you?” “How did participating in the HOC class affect you or your family?” “Would you recommend this class to a friend?”). Participants received $25 gift cards for the baseline, post assessment, and 4-month follow-up assessment (for a total of $75 if they completed all assessments).

ANALYSES

Suquamish High School

We evaluated the high school sample by comparing the baseline versus end-of-year and 4-month follow-up assessments. An overall analysis across time points was conducted using Friedman’s Two-Way Analysis of Variance by Ranks, which is a nonparametric analog of the parametric repeated measures analysis of variance. A Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test, a nonparametric test of paired-sample repeated measures, was used to follow up significant differences on the Friedman’s test.

Suquamish/PGST Workshops

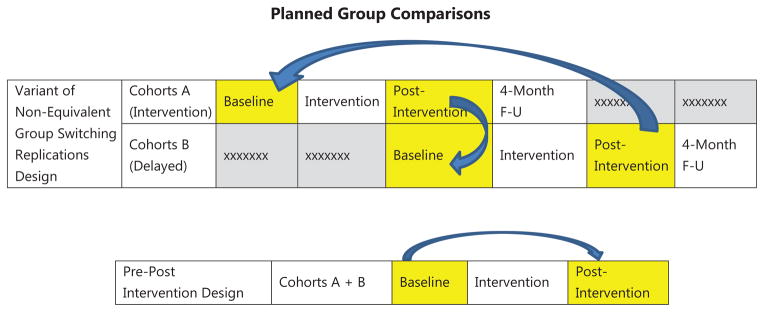

We evaluated the intensive workshops using a quasi-experimental design, a variant of the non-equivalent group, switching replication design (Trochim, 2006). This design, while not involving random assignment to conditions, is thought to be very strong with respect to internal validity. It also allowed for two independent implementations of the intervention in each tribal community, potentially enhancing external validity or generalizability. In this design, there are typically two groups, both of which receive the intervention, but in a sequential process. In the first phase of the design, both groups are assessed at baseline, but only one receives the intervention; both are then reassessed at the post-intervention point. In the second phase, the original comparison group is now provided the intervention while the original cohort serves as the control. This design is similar to a wait-list control design and might be thought of as two parallel pre-/post-treatment control designs grafted together. That is, when the treatment is replicated, the two groups switch roles—the original control group becomes the treatment group in phase 2. By the end of the study, all participants have received the treatment. Because participants in all groups eventually receive the intervention, which was a condition stipulated by our tribal CABs, it is considered to be one of the most ethically feasible quasi-experimental designs.

The design and the comparisons are shown in Figure 3. In this variant of the design, Cohort A has a baseline assessment, receives the intervention over the specified time period, and has a post-intervention assessment and a 4-month follow-up. After a delay, Cohort B has a baseline assessment, receives the intervention over the specified time period, and has a post-intervention assessment and a 4-month follow-up. This design allows two sets of comparisons between those groups that have received the intervention and control groups. In addition, it is also possible to combine cohorts and compare pre-/post-intervention and 4-month follow-up scores. Given the small sample sizes and the non-normal distributional properties of scores, we conducted nonparametric analyses (Conover, 1999; De Muth, 2009; Nachar, 2008; Trochim, 2006). Analyses involving independent group comparisons used the Mann-Whitney-U statistic. For repeated measures across time, in a manner similar to that described for the tribal high school analyses, we conducted an overall analysis using Friedman’s Two-Way Analysis of Variance by Ranks, followed by post hoc Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test.

Figure 3.

Planned Group Comparisons

We hypothesized that involvement in the intervention would lead to increased levels of cultural identification and participation, hope/optimism/self-efficacy, and knowledge about substance abuse, and to lower levels of substance use. Based on directional hypotheses, 1-tailed probabilities were used against which to judge significance of differences.

RESULTS

Suquamish High School

Data were available for all 8 participants at baseline, 6 (75%) at the end of school and 7 (87.5%) at the 4-month follow-up assessment. At baseline, 50% of students reported having smoked cigarettes and having used marijuana; for those who reported prior use, the age of first use was 13.0 years and 10.5 years for tobacco and marijuana, respectively. Nearly two thirds (62.5%) of the students had consumed alcohol beyond a mere sip (e.g., drank a glass, can, or bottle of alcohol); their age of initial use was 12.2 years. One quarter of the sample had used pain pills to get high, with age of initial use being 16.5 years. Nearly two-thirds (62.5%) reported frequent/regular participation in cultural activities, with the remaining 37.5% having moderate levels of involvement (a few times per month); 71.4% indicated that they participated in such activities to the extent that they would like.

The results of the Friedman’s test indicated that there was an overall difference across time for the measures of hope/optimism/self-efficacy (X2 = 6.50, p = 0.020) and substance use (X2 = 7.43, p = 0.012). Post hoc analyses indicated that the level of hope/optimism/self-efficacy increased significantly from the beginning to the end of the school year (p = 0.021) and remained significantly higher at the 4-month follow-up compared to the beginning of the school year (p = 0.023). Substance use reduced significantly from the beginning to the end of the school year (p = 0.021); however, although it was still 26% lower at the 4-month follow up than at the beginning of school, it was no longer significantly different (p = 0.051). No differences were found on the measure of cultural identification and participation or knowledge substance abuse from the beginning of school to either the end of school or the 4-month follow-up.

Suquamish/PGST Workshops

Of the 23 participants who started the workshops, post-intervention data are available for 19 (82.6%). Of the 12 participants in the first series of workshops (Cohort A), 11 completed both the post-intervention and 4-month follow-up assessments (91.7%); of the 11 participants in the second series (Cohort B), 8 completed both post-intervention and 4-month follow-up assessments (72.7%). These rates represent an 82.6% follow-up rate at 4 months for the two cohorts combined.

In an initial analysis, we compared the two cohorts with respect to their baseline scores on the four primary measures to evaluate their comparability. There were no differences on any of these primary measures between Cohorts A and B from either community or the combined communities at baseline, indicating equivalence of participants prior to involvement in the workshops.

At baseline, over half of the combined cohorts had peviously smoked cigarettes (54.5%), while two thirds had consumed alcohol (68.2%) and used marijuana (66.7%). The ages of first use of these substances among those who had used them were 11.4, 12.1, and 13.1 years, respectively; 9.1% had used pain pills to get high. Only 39.1% of of the combined cohorts reported frequent/regular involvement in cutural activities, while an equal percentage reported low levels of involvement (once a month or less); the remaining 21.7% had moderate levels of involvement (a few times per month). Fewer than half (43.5%) of those in the combined cohorts felt that they were involved in such activities to the extent that they wanted to be.

Differences were found when those who had completed the workshop intervention (Cohort A post-intervention and Cohort B post-intervention) were compared to those who had not yet been exposed. In comparing the post-intervention assessment of Cohort A with the baseline assessment of Cohort B, Cohort A had significantly higher levels of hope/optimism/self-efficacy (Mann-Whitney-U = 20.5, Z = −2.639, p = .004, 1-tailed), and lower levels of substance use than those who had not yet received the intervention (Mann-Whitney-U = 34.5, Z = 1.71, p = .043, 1-tailed). However, neither the differences in hope/optimism/self-efficacy (U = 73.0, Z = 0.43, p = 0.333) nor those in substance use (U = 76.0, Z = 0.146) were maintained when comparing Cohort A 4-month follow-up to Cohort B baseline values. Also, there were no differences between groups with respect to cultural identity/practices when comparing Cohort A post-intervention or 4-month follow-up to Cohort B baseline values, nor were differences found between Cohort A post-intervention and Cohort B baseline values with respect to knowledge about substance abuse; however, the comparison between Cohort A 4-month follow-up and Cohort B baseline values approached significance (U = 92.5, Z = 1.63, p = 0.051).

In the second comparison within the switching replication design, the post-intervention and 4-month follow-up scores for Cohort B were compared to the baseline scores of Cohort A. Youth who had received the intervention had significantly higher levels of cultural identity/practices (Mann-Whitney-U = 26.5, Z = −1.669, p = 0.048, 1-tailed), hope/optimism/self-efficacy (Mann-Whitney-U = 7.00, Z = −3.186, p = 0.001, 1-tailed), and knowledge about substance abuse (Mann-Whitney-U = 20.0, Z = −2.198, p = 0.014, 1-tailed) compared to those who had not yet received it. The differences with resepct hope/optimism/self-efficacy (U = 84.5, Z = 2.816, p = 0.0024) and knowledge about substance abuse (U = 68.5, Z = 2.24, p = 0.013) persisted at the 4-month follow-up, while cultural involvement approached significance at the 4-month follow-up (U = 67.0, Z = 1.466, p = 0.071). While substance use was 38% lower for those who had received the intervention compared to the baseline of those who had not, this difference was not significant (p = 0.193) at post intervention or at the 4-month follow-up (p = 0.439).

The third set of analyses combined the cohorts and examined changes from baseline to post intervention and 4-month follow-up, utilizing the Friedman’s test followed by post hoc Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test. Overall, there were significant differences across time on the measures of hope/optimism/self-efficacy (X2 =7.914, p = 0.01), substance use (X2 = 6.821, p = 0.017), and knowledge about substance abuse (X2 = 4.966, p = 0.042). There was a significant increase in hope/optimism/self-efficacy (Z = −2.088, p = 0.019, 1-tailed) and a reduction in substance use (Z = −1.990, p = 0.024, 1-tailed) associated with receiving the intervention from baseline until completion of the three workshops. These differences in hope/optimism/self-efficacy (Z = −3.042, p = 0.001) and substance use (Z = −1.838, p = 0.033) remained significant at the 4-month follow-up compared to baseline. Although knowledge about drugs of abuse was not significant at post intervention (Z = −1.491, p = 0.068), it was significantly different at the 4-month follow-up (Z = −2.502, p = 0.006).

Qualitative Information

Qualitative data from the Phase I external evaluation key stakeholder interviews and focus groups (Randall, 2008), and from the open-ended questions asked of youth participants at post intervention, reflect the communities’ and youths’ positive appraisal of the project, as well as the perceived community- and participant-level benefits attributed to involvement. This finding is reflected in the following exemplary quotations:

Responses from adult community members:

I think that the way that they have been able to combine the culture activities with the drug and alcohol prevention information and being able to combine those two things into one class has really been instrumental. I don’t think anybody has done that really well in combining those two things.

I think that everyone benefits from it because even people who aren’t involved in Healing of the Canoe, you know, they’re still involved in the sense that the Healing of the Canoe is thinking about them. And weighing out all of these things that happen and basing it and really trying to see how it ripples throughout the rest of the community. Because I can tell you my experience, or somebody else can tell you their experience, but really it has to do with the rest of the community. And so Healing of the Canoe, definitely I think it benefits everybody that is in the surrounding area and then even farther.

Everyone has input into the project. We review the input and the kids review the input. It is a good way of doing it. Something everyone collaborated on. I saw my grandson blossom into a leader.

Responses from youth participants:

I think that going to…or having Healing of the Canoe as a class in high school definitely helped me and also made changes in some of the other kids’ lives.

It was a good learning opportunity and a great experience. Good way to learn knowledge about drugs and alcohol. The people that I got a chance to learn with we strengthened our bond over the three workshops. Gained a better friendship with the other students.

It’s very educational with culture and drugs and alcohol, expressing yourself, building a lil’ community in a lil’ class.

DISCUSSION

Community Engagement

HOC project development was predicated on an increased empirical and Indigenous knowledge evidence base suggesting that programs derived from the community and incorporating tribal-specific culture, values, and traditions are more acceptable, and may have a more positive impact, than interventions developed with majority populations (Brown et al, 2012; Hawkins et al., 2004; Kenyen & Hanson, 2012; Lowe et al., 2012; Moran & Reaman, 2002; Okamoto et al., 2014). The development process incorporated a number of key components previously noted as contributing to successful development, adaptation, and acceptance of interventions in AI/AN communities (Moran & Reaman, 2002; Trimble, 1992). These included establishing a collaborative working relationship and actively involving the communities; incorporating local tribal cultural values, customs, lifeways, and activities; and training community paraprofessionals to deliver the program. Clearly, our development process incorporated the spirit of and processes inherent in CBPR/TPR, and exemplified the principles of community engagement (Duffy et al., 2011). The curricula developed in the HOC project and evaluated in the present paper were based on these principles. They incorporate evidence-based components from standard interventions (e.g., social skills training, decision making, problem solving, emotional regulation), and were adapted to be consistent with and presented in the context of the values, culture, and traditions associated with the Canoe Journey and of the Suquamish Tribe and PGST. Such skills are important to complete the Canoe Journey successfully, as well as to navigate through life without being pulled off course by alcohol and drugs (Hawkins & La Marr, 2012).

Overall Findings

Despite the small sample sizes involved, there is support for the delivery of the expanded Holding Up Our Youth curriculum in the high school; participation was associated with increased hope/optimism/self-efficacy from baseline through the 4-month follow-up and with reduced substance use from baseline until the end of the school year. Similarly, there is support for the adapted Holding Up Our Youth and Navigating Life the S’Klallam Way curricula delivered in the workshop format. Workshop participants consistently demonstrated higher levels of hope/optimism/self-efficacy across comparisons. In at least one of the cohort analyses, participation in the curricula also was associated with higher levels of cultural identity and practices, knowledge of alcohol and drugs, and lower levels of substance use than for those youth who had not yet participated. These differences were all in the hypothesized direction. Thus, the curricula appear to have demonstrated effectiveness in addressing the primary concern identified by the communities—namely, youth substance use and abuse.

Cultural Identity and Participation in Cultural Activities

Somewhat surprisingly, we did not find consistent evidence of increased cultural identity among participants, or an increase in their cultural activities. It is possible that the measures utilized did not fully assess these constructs adequately; the addition of a more qualitative approach might have been more helpful in identifying them. A positive change was found in one of the analyses in the cohort comparisons, but not in the other, and not in the high school sample. The level of cultural activity in the high school sample at baseline was already quite high; that is, 100% of the high school youth reported moderate to high levels of participation (at least a few times per month), and over 70% indicated that they were satisfied with this level. As such, there may have been a “ceiling effect” with less probability of change among these youth. In contrast, youth who participated in the workshops were less actively involved in cultural practices at baseline. Nearly 40% of the combined cohorts reported low levels of involvement (once a month or less), with 56.5% at baseline saying that they were not participating as much as they would like. Given that the intervention demonstrated an increase in traditional activities in this group, it may be most effective among those youth who enter the program with lower levels of cultural involvement––consistent with one of the goals the communities had identified.

A community-based cultural mental health intervention for AI/AN youth and their families in the Southwest had a similar finding (Goodkind, LaNoue, Lee, Freeland, & Freund, 2012). While participants demonstrated increased cultural identity, the intervention did not lead to increased participation in traditional cultural activities. The authors suggest that, while youth may have gained cultural knowledge and interest, it may take time to translate this knowledge into practice. They also noted the importance of providing ongoing opportunities for youth to participate in traditional cultural learning and activities. Consistent with this latter point, the communities in the present study incorporated many activities to ensure that youth had opportunities to participate and to increase their interactions with other tribal members, including community events, presentations in classes by Elders and mentors, and projects that introduced students to community members and tribal programs.

Increased Hope/Optimism/Self-efficacy

The most consistent finding across all the analyses was an increase in, and maintenance of, a sense of hope/optimism/self-efficacy. Hope and optimism represent core competencies in substance abuse prevention and are components of positive youth development (Haegerich & Tolan, 2008; Lam et al., 2011). Higher levels of hope and optimism and a positive future orientation have also been found to predict lower levels of depressive symptoms, alcohol use, and heavy drinking in early adolescence and into early adulthood among Canadian Aboriginal youth (Ames, Rawana, Gentile, & Morgan, 2015; Rawana & Ames, 2012). As such, substance abuse prevention interventions should focus on increasing hope and optimism as elements of positive youth development (Lam et al., 2011).

Some researchers have suggested that substance abuse prevention programs for AI/AN youth might be more effective if they target entire communities rather than specific individuals (Hawkins et al., 2004). Although the HOC interventions focused on the individual level, community members actively participated in their development and implementation, the project was conducted in partnership with tribal agencies, tribal members were employed as research and facilitator staff, and the research team made regular presentations to the CABs and Tribal Councils and provided ongoing communication about the project in newspaper articles and community meetings. In addition, university-based team members spent (and still spend) a considerable amount of time in the communities, attending events and ceremonies and volunteering when appropriate. The project’s early Phase I university-community partnership development process was selected by representatives from federal health agencies as one of 12 case examples of the effective use of the principles of community engagement (Duffy, Aguilar-Gaxiola, McCloskey, Ziegahn, & Silberberg, 2011; Thomas et al., 2009). These efforts led to the acceptance of the research and curricula by, and the perceived impact on, the broader community. It is clear from qualitative statements from community members and youth participants that the interventions were viewed as beneficial at both the individual participant and community levels.

Study Limitations

The present study has a number of limitations. First, the study must be viewed as preliminary in nature. The results are based on a small sample derived from a yearlong high school class and a series of intensive workshops. While both tribal communities are relatively small, the sample also was restricted due to community-driven changes in the target age group and the availability of venues in which the curricula were delivered (e.g., the Suquamish tribal high school closure; it should be noted that the high school has reopened, two of the high school teachers have been trained in the delivery of the Holding Up Our Youth curriculum, and the intervention is once again being delivered as part of the school’s offerings). While the small sample size may limit statistical power and generalizability, significant changes in key outcomes still were obtained over time and across settings. The fact that differences were obtained in both the high school and the workshop samples also speaks to the flexibility and adaptability of the core curricula.

A second concern was the design employed in evaluating the curricula. The high school evaluation used a pre-/post design and can be faulted for lack of a non-intervention comparison group. However, given the preliminary nature of the study and the small size of the student body, this was the most feasible approach available. We employed comparison groups to evaluate the workshops in a quasi-experimental design. We considered random assignment; however, our CABs both objected. They felt that if the proposed intervention might be effective, then it should be provided to all youth. As such, we chose the non-equivalent switching replication design, which has been described as very strong with respect to internal validity, and as one of the most ethically feasible quasi-experimental designs because participants in all groups eventually receive the intervention.

A third potential limitation was the conduct of the study in two different tribal communities with curricula developed in each. However, the core elements of the two curricula were the same; what differed were the tribal-specific traditions, values, and cultural activities that were inserted into the placeholders for each session. This approach facilitates the generalizability of the curricula across tribal communities while maintaining their evidence-based components, and allows integration of cultural elements in a way that accommodates the diversity across AI/AN populations (Hawkins & La Marr, 2012; Moran & Reaman, 2002). This flexibility is important now that the project is in Phase III, a dissemination phase in which we are providing 2-day trainings to tribal communities. These trainings cover the curricula, how to assess community needs and resources, how to engage the community in the curriculum adaptation process, how to determine a metaphor that best fits the community’s context (e.g., we have trained a number of non-coastal tribes for which the canoe is not appropriate, but other types of journeys or metaphors fit), and how to tailor the curriculum with tribal-specific values, traditions, and activities to fill into the placeholders. In addition, we hold weekly technical assistance calls and/or webinars for individuals who have participated in the trainings. From February through December 2014, we trained 85 individuals from 17 tribes and five tribal organizations to adapt and implement the generic HOC curriculum template for their communities or organizations.

CONCLUSION

While acknowledging the preliminary nature of the current report, and the need for additional research with larger samples, the present findings suggest that the community-derived, culturally grounded prevention curricula represent promising practices. Integrating evidence-based components of positive youth development and tribal-specific culture, traditions, and values, the curricula have the potential of reducing substance use; increasing hope, optimism, and self-efficacy; and facilitating cultural identity. Further, it appears that a number of different delivery formats can accommodate the needs of different tribal communities. Consistent with the skills needed to successfully complete the Canoe Journey, the curricula have the potential of helping AI/AN youth stay on course as they navigate life’s journey.

Acknowledgments

The project described in this paper was supported by Grant Number R24MD001764 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, U.S. National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the National Institutes of Health. We would like to acknowledge the Suquamish Tribe, its Elders, its members, the Suquamish Cultural Co-Operative, and the Tribal Council and the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, its Elders, its members, the Chi-e-chee Network, and the Tribal Council for inviting us into their communities and being full partners in the research process. We would also like to thank and acknowledge Dr. Nina Wallerstein and the Qualitative Research Team, Research for Improved Health Study, Center for Participatory Research, University of New Mexico, for developing and providing permission to use Figure 1, Healing of the Canoe: Social Worlds.

Biographies

Dr. Donovan is Director of the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington and Professor in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA. He is Principal Investigator of the Healing of the Canoe project and the corresponding author and can be reached at ddononvan@uw.edu.

Dr. Thomas is a Research Scientist at the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington and the Indigenous Wellness Research Institute at the University of Washington School of Social Work, Seattle, WA, and currently the Director of the Suquamish Tribe Wellness Program.

Ms. Sigo is with the Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Reservation, Suquamish, WA. She is the Principal Investigator of the Suquamish component of the Healing of the Canoe project and served as one of the Facilitators. She is currently the Director of the Grants Department and member of the Tribal Council of the Suquamish Tribe.

Ms. Laura Price is with the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, Port Gamble Reservation, Little Boston, WA. She is the Principal Investigator of the Port Gamble S’Klallam component of the Healing of the Canoe project and served as one of the Facilitators. She is also the skipper of the Tribe’s Youth Canoe.

Dr. Lonczak was a Research Scientist with the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute and is currently a Research Project Coordinator, Harborview Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, at the University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA.

Mr. Nigel Lawrence is with the Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Reservation, Suquamish, WA. He served as one of the Healing of the Canoe Facilitators for the Suquamish Tribe. He is a member of the Suquamish Tribal Council and is a skipper of the Tribe’s Youth Canoe.

Ms. Ahvakana is with the Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Reservation, Suquamish, WA. She served as one of the Healing of the Canoe Facilitators for the Suquamish Tribe. She is currently the Program manager for the Suquamish Tribe’s Sports & Recreation Department.

Ms. Austin is a Research Coordinator for the Healing of the Canoe project at the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Ms. Albie Lawrence is with the Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Reservation, Suquamish, WA. She served as one of the Healing of the Canoe Facilitators for the Suquamish Tribe.

Mr. Joseph Price is with the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, Port Gamble Reservation, Little Boston, WA. He served as one of the Healing of the Canoe Facilitators for the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe. He is a Youth Services Specialist and is a member of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Canoe Family.

Ms. Purser is with the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, Port Gamble Reservation, Little Boston, WA. She served as the Healing of the Canoe Youth Specialist for the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe.

Ms. Bagley is with the Suquamish Tribe, Port Madison Reservation, Suquamish, WA. She served as the Healing of the Canoe Youth Specialist for the Suquamish Tribe She currently works as an One-on-One Aide in the Suquamish Tribe’s Early Learning Center.

References

- Ames ME, Rawana JS, Gentile P, Morgan AS. The protective role of optimism and self-esteem on depressive symptom pathways among Canadian Aboriginal youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(1):142–154. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball J, Janyst P. Enacting research ethics in partnerships with indigenous communities in Canada: “Do it in a good way. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics. 2008;3(2):33–51. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.2.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Castro FG. A heuristic framework for the cultural adaptation of interventions. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice. 2006;13(4):311–316. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=2&sid=7b6134fc-9a7c-4bad-921ab8ab9fbb826a%40sessionmgr113&hid=105. [Google Scholar]

- Baydala LT, Sewlal B, Rasmussen C, Alexis K, Fletcher F, Letendre L, Kootenay B. A culturally adapted drug and alcohol abuse prevention program for Aboriginal children and youth. Progress in Community Health Partnerships. 2009;3(1):37–46. doi: 10.1353/cpr.0.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. Trends in Indian adolescent drug and alcohol use. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1992;5(1):1–12. doi: 10.5820/AI/AN.0501.1990.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F. Trends in drug use among American Indian students and dropouts, 1975–1994. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(11):1594–1598. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.11.1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauvais F, Jumper-Thurman P, Helm H, Plested B, Burnside M. Surveillance of drug use among American Indian adolescents: Patterns over 25 years. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2004;34(6):493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brave Heart MYH, DeBruyn LM. The American Indian Holocaust: Healing historical unresolved grief. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 1998;8(2):56–78. doi: 10.5820/AI/AN.0802.1998.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown BG, Baldwin JA, Walsh ML. Putting tribal nations first: Historical trends, current needs, and future directions in substance use prevention for American Indian and Alaska Native youths. In: Camp-Yeaky C, Notaro SR, editors. Advances in education in diverse communities: Research, policy and praxis. Volume 9 - Health disparities among under-served populations: Implications for research, policy and praxis. Bingley, United Kingdom: Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2012. pp. 3–47. [Google Scholar]

- Burhansstipanov L, Christopher S, Schumacher SA. Lessons learned from community-based participatory research in Indian country. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 2):70–76. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004s10. Retrieved from http://moffitt.org/research--clinical-trials/cancer-control-journal/cancer-culture-and-literacy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JY, Davis JD, Du Bois B, Echo-Hawk H, Erickson JS, Goins RT, Stone JB. Culturally competent research with American Indians and Alaska Natives: Findings and recommendations of the first symposium of the work group on American Indian Research and Program Evaluation Methodology. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2005;12(1):1–21. doi: 10.5820/AI/AN.1201.2005.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro FG, Barrera M, Jr, Martinez CR., Jr The cultural adaptation of prevention interventions: Resolving tensions between fidelity and fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/B:PREV.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Saha R, Lachapelle P, Jennings D, Colclough Y, Cooper C, Webster L. Applying Indigenous community-based participatory research principles to partnership development in health disparities research. Family & Community Health. 2011;34(3):246–255. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318219606f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher S, Watts V, McCormick AK, Young S. Building and maintaining trust in a community-based participatory research partnership. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(8):1398–1406. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.125757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu JP, Huynh L, Area’n P. Cultural adaptation of evidence-based practice utilizing an iterative stakeholder process and theoretical framework: Problem solving therapy for Chinese older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2012;27:97–106. doi: 10.1002/gps.2698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran PA, Marshall CA, Garcia-Downing C, Kendall E, Cook D, McCubbin L, Gover RM. Indigenous ways of knowing: Implications for participatory research and community. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):22–27. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.093641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover WJ. Practical nonparametric statistics. 3. New York, NY: Wiley & Sons; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL, Friesen BJ, Jivanjee P, Gowen LK, Bandurraga A, Matthew C, Maher N. Defining youth success using culturally appropriate community-based participatory research methods. Best Practices in Mental Health. 2011;7(1):94–114. Retrieved from http://web.b.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=20311969-faba-44d9-84d5-754a3a83896f%40sessionmgr114&vid=4&hid=125. [Google Scholar]

- Cross TL, Friesen BJ, Maher N. Successful strategies for improving the lives of American Indian and Alaska Native youth and families. Focal Point. 2007;21(2):10–13. http://www.pathwaysrtc.pdx.edu/pdf/fpS0704.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- De Muth JE. Overview of biostatistics used in clinical research. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2009;66(1):70–81. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy R, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, McCloskey DJ, Ziegahn L, Silberberg M. Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement, editor. Principles of Community Engagment. 2. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2011. Successful examples in the field; pp. 57–89. [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Duran B, Brave Heart MYH, Yellow Horse-Davis S. Healing the American Indian soul wound. In: Danieli Y, editor. International handbook of multigenerational legacies of trauma. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. pp. 341–354. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards Y. Cultural connection and transformation: Substance abuse treatment at Friendship House. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):53–58. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. tribal participatory research: Mechanisms of a collaborative model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32(3–4):207–216. doi: 10.1023/B:AJCP.0000004742.39858.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. Balancing empiricism and local cultural knowledge in the design of prevention research. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(2 Suppl 3):iii44–iii55. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP. “We never was happy living like a Whiteman”: Mental health disparities and the postcolonial predicament in American Indian communities. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;40(3–4):290–300. doi: 10.1007/s10464-007-9136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Alcantara C. Identifying effective mental health interventions for American Indians and Alaska Natives: A review of the literature. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(4):356–363. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Calf Looking PE. American Indian culture as substance abuse treatment: Pursuing evidence for local intervention. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):291–296. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.628915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gone JP, Trimble JE. American Indian and Alaska Native mental health: Diverse persepctives on enduring disparities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2012;8:131–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodkind J, LaNoue M, Lee C, Freeland L, Freund R. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial findings from a community-based cultural mental health intervention for American Indian youth and their families. Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40(4):381–405. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen LK, Bandurraga A, Jivanjee P, Cross T, Friesen BJ. Development, testing, and use of a valid and reliable assessment tool for urban American Indian/Alaska Native youth programming using culturally appropriate methodologies. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work. 2012;21(2):77–94. doi: 10.1080/15313204.2012.673426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray N, Nye PS. American Indian and Alaska Native substance abuse: Co-morbidity and cultural issues. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2001;10(2):67–84. doi: 10.5820/AI/AN.1002.2001.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haegerich TM, Tolan PH. Core competencies and the prevention of adolescent substance use. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development. 2008;122:47–60. doi: 10.1002/cd.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Marlatt GA. Preventing substance abuse in American Indian and Alaska native youth: Promising strategies for healthier communities. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130(2):304–323. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins EH, La Marr CJ. Pulling for Native communities: Alan Marlatt and the Journeys of the Circle. Addiction Research and Theory. 2012;20(3):236–242. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2012.657282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holkup PA, Tripp-Reimer T, Salois EM, Weinert C. Community-based participatory research: An approach to intervention research with a Native American community. Advances in Nursing Science. 2004;27(3):162–175. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200407000-00002. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2774214/pdf/nihms127083.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Indian Health Service. IHS Fact Sheets: Indian Health Disparities. Rockville, MD: Author; 2015. Retreived from http://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/factsheets/disparities/ [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. How far have we come in reducing health disparities? Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2012. p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BE. Canoe journeys and cultural revival. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 2012;36(2):131–141. Retrieved from http://aisc.metapress.com/content/w241221710101249/fulltext.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Jumper-Thurman P, Plested BA, Edwards RW, Foley R, Burnside M. Community readiness: The journey to community healing. In: Nebelkopf E, Phillips M, editors. Healing and mental health for Native Americans: Speaking in red. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon DYB, Hanson JD. Incorporating traditional culture into positive youth development programs with American Indian/Alaska Native youth. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6(3):272–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00227.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CM, Lau PSY, Law BMF, Poon YH. Using positive youth development constructs to design a drug education curriculum for junior secondary students in Hong Kong. ScientificWorld. 2011;11:2339–2347. doi: 10.1100/2011/280419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMarr J, Marlatt GA. Canoe Journey Life’s Journey: A life skills manual for Native adolescents. Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing and Educational Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lane DC, Simmons J. American Indian youth substance abuse: Community-driven interventions. Mt Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2011;78(3):362–372. doi: 10.1002/msj.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larios SE, Wright S, Jernstrom A, Lebron D, Sorensen JL. Evidence-based practices, attitudes, and beliefs in substance abuse treatment programs serving American Indian and Alaska Natives: A qualitative study. American Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):355–359. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.629159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeaux D, Christopher S. Contextualizing CBPR: Key principles of CBPR meet the Indigenous research context. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2009;7(1):1–25. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2818123/pdf/nihms144307.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonczak HSV, Thomas LR, Donovan D, Austin L, Sigo RLW, Lawrence N the Suquamish Tribe. Navigating the tide together: Early collaboration between tribal and academic partners in a CBPR study. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2013;11(3):395–408. Retrieved from http://www.pimatisiwin.com/online/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/05LonczakThomas.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, Liang H, Riggs C, Henson J. Community partnership to affect substance abuse among Native American adolescents. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):450–455. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, Riggs C, Henson J. Principles for establishing trust when developing a substance abuse intervention with a Native American community. Creative Nursing. 2011;17(2):68–73. doi: 10.1891/1078-4535.17.2.68. http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1078-4535.17.2.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Larimer ME, Mail PD, Hawkins EH, Cummins LH, Blume AW, Gallion S. Journeys of the Circle: A culturally congruent life skills intervention for adolescent Indian drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(8):1327–1329. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000080345.04590.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michell H. Gathering berries in northern contexts: A Woodlands Cree metaphor for community-based research. Pimatisiwn: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 2009;7(1):65–73. Retrieved from http://www.pimatisiwin.com/uploads/July_2009/06Michell.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Moran JR, Reaman A. Critical issues for substance abuse prevention targeting American Indian youth. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2002;22(3):201–233. doi: 10.1023/A:1013665604177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nachar N. The Mann-Whitney U: A test for assessing whether two independent samples come from the same distribution. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2008;4(1):13–20. Retrieved from http://www.tqmp.org/Content/vol04-1/p013/p013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Brochures and Fact Sheets. Bethesda, MD: Author; 2011. Retrieved from http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA for Teens. Drug facts. Bethesda, MD: Author; 2011. Retrieved from http://teens.drugabuse.gov/facts/index.php. [Google Scholar]