Abstract

Data from 508 Caucasian children in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development shows that the DRD4 (but not 5-HTTLPR) polymorphism moderates the effect of child care quality (but not quantity or type) on caregiver-reported externalizing problems at 54 months and in kindergarten and teacher-reported social skills at kindergarten and first grade—but not thereafter. Only children carrying the 7-repeat allele proved susceptible to quality-of-care effects. The behavior-problem interactions proved more consistent with diathesis-stress than differential-susceptibility thinking, whereas the reverse was true of the social-skills' results. Finally, the discerned gene-X-environment interactions did not account for previously reported parallel ones involving difficult temperament in infancy.

Keywords: Child Care, DRD4, 5-HTTPLR, GXE, Diathesis Stress, Differential Susceptibility, Externalizing Behavior Problems, Social Competence

Debate has long characterized discussion of the effects of child care on children's development (Fox & Fein, 1990; Karen, 1998), though this is clearly more true regarding adverse effects of lots of time spent in child care (Belsky, 1986, 1988, 1990; Clarke-Stewart, 1989; Phillips, McCartney, Scarr, & Howes, 1987; Vandell, Belsky, Burchinal, Steinberg, & Vandergrift, 2010), perhaps particularly centers (Belsky et al., 2007), than with respect to quality of care. After all, it is not only widely believed that quality of child care is an important determinant of children's functioning, but there is long-standing evidence consistent with this claim (e.g., Howes, 1988; Peisner-Feinberg & Burchinal, 1997; Vandell, Henderson, & Wilson, 1988).

Important to appreciate, however, is that inconsistency exists within the research literature even with respect to the effects of child care quality. Perhaps most notable in this regard is the general failure of careful measurements of how attentive, responsive and stimulating caregivers were to children enrolled in the large-scale NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (SECCYD) to predict children's social adjustment after age three and before age 15, even as it consistently predicted children's cognitive-linguistic functioning and academic achievement during this developmental period (NICHD ECCRN, Belsky, Vandell, et al., 2007; 2003; Vandell, et al., 2010).

For the past decade or so, developmentalists studying the effects of diverse environmental experiences and exposures have become ever more aware that individuals may differ in whether and how they are affected by their developmental experiences; and, most importantly for the research reported herein, that this may be a function of genetics (Caspi & Moffitt, 2006). Although some have questioned the replicability of particular gene-X-environment (GXE) interactions that have appeared in the published literature (Duncan & Keller, 2011; Risch et al., 2009), it would certainly seem mistaken to throw the genetic-moderation-of-environmental-influences baby out with the bathwater (Caspi, Hariri, Holmes, Uher, & Moffitt, 2010; Karg, Burmeister, Shedden, & Sen, 2011; Rutter, Thapar, & Pickles, 2009; Uher & McGuffin, 2010). Indeed, here we take advantage of data from the NICHD SECCYD to examine for the first time whether two particular genetic factors might moderate effects of quality, quantity and type of child care on children's teacher-rated externalizing behavior problems and social skills. In so doing, we are positioned to shed some light on at least one reason why child care effects have been subject to so much debate. After all, if at least some child care effects prove to be genetically moderated, varying across studies due to the genetic make-up of samples, this could account for some of the inconsistency in the literature. To be appreciated, however, is that because the sample studied here is limited in size, is not epidemiological in character and we do not have a second sample on which to replicate any detected GXE effects, the research presented herein represents a proof-of-concept effort. While it can shed light on whether child care effects could vary as a function of children's genotype, it is not positioned to provide compelling evidence that they certainly do. Additional research will be required before such could be claimed.

The Moderation of Child Care Effects

As it turns out, there is evidence that some child care effects vary as a function of children's characteristics of individuality. Pluess and Belsky (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2009, 2010) found, upon further analyzing NICHD SECCYD data, that early temperament played a moderational role with respect to effects of quality of care; and it did so in ways consistent with some other work evaluating this possibility (Crockenberg, 2003; Phillips, Fox, & Gunnar, 2011). More specifically, children who were rated as more difficult to care for in their first six months of life, including being more negatively emotional, proved to be more affected by quality—but not quantity or type—of care than did other children, at least with respect to externalizing problems and social skills. Just as intriguing was the fact that such children were affected in a for-better-and-for-worse manner (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007). That is, children with histories of difficult temperament in infancy scored higher on behavior problems than all other children across the preschool, middle-childhood and adolescent years if they had experienced low quality care, yet lower on behavior problems than others if they had experience high quality care (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2009, 2010).

Models of Environmental Action

Such moderational effects of temperament vis-à-vis child care experiences were particularly interesting in that they proved more consistent with the differential-susceptibility hypothesis (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, et al., 2007; Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2011) than the prevailing diathesis-stress model of environmental action (Zuckerman, 1999). The long-standing and highly influential diathesis-stress framework exclusively addresses the issue of who is most susceptible to the negative effects of adverse environmental experiences and exposures (e.g., poverty, harsh parenting), essentially presuming that some are more vulnerable than others as a result of a personal characteristic (e.g., difficult temperament, risk allele). It is this conceptual framework that informed the first gene-X-environment interaction research examining the effects of maltreatment on antisocial behavior (Caspi et al., 2002) and of life event stress on depression (Caspi et al., 2003).

Notably, the diathesis-stress paradigm does not in any way address differential response to positive, supportive or enriching environmental experiences and exposures (e.g., high-quality child care, sensitive parenting); and this is where it differs from the differential-susceptibility perspective. Rather than regarding some individuals as exclusively more vulnerable than others to adversity due to some endogenous factor, the differential- susceptibility model of environmental action presumes that those most likely to be negatively affected by some adverse environmental condition are also most likely to benefit from a supportive one. Thus, whereas diathesis-stress thinking regards some as more vulnerable to adversity, differential-susceptibility thinking stipulates that those most susceptible to negative environmental influences are simultaneously most susceptible to positive ones as well. That is, they are not so much vulnerable as malleable or developmentally plastic—for better and for worse. Intriguingly, a good deal of gene-X-environment (GXE) interaction work, the focus of the current report, provides evidence consistent with differential susceptibility theorizing (Belsky et al., 2009; Belsky & Pluess, 2009; Ellis, et al., 2011).

Gene-X-Environment Interaction

In the current report, we extend examination of the potential moderating effect of child attributes with respect to the potential influence of day care (i.e., quality, quantity, and type) on teacher-rated social adjustment by focusing on children's genetic make-up. In particular, in the GXE analyses reported herein we explore the prospect that the serotonin transporter gene, 5-HTTLPR, or the DRD4 dopamine-receptor gene moderate the effect of child care experience on teacher-rated externalizing problem behavior and social skills, perhaps accounting for why quality of care in particular did not predict—as a main effect— social adjustment from just before school entry to the last year of elementary school in the NICHD SECCYD (Belsky et al., 2007). We restrict our analyses to these two polymorphisms, despite the fact that a range of VNTRs and SNPs have been genotyped on the SECCYD cohort, because they have proven most often in GXE research to function as “plasticity genes” in line with differential susceptibility rather than just “risk alleles” consistent with diathesis-stress models of environmental action (Belsky & Pluess, 2009).

There a seveveral additional reasons to focus on the DRD4 polymorphism in this study of the effects of quality, quantity and type of care on externalizing problem behavior and social skills. First, DRD4 has been linked with aggression (and antisocial behavior) in children and adolescents (Beaver et al., 2007; Oades et al., 2008; Schmidt, Fox, Rubin, Hu, & Hamer, 2002), a core component of externalizing problems which is one of the two developmental outcomes that are the focus of this inquiry and which has been the source of so much controversy with respect to day-care effects (Crockenberg, 2003; Fox & Fein, 1990; Langlois & Liben, 2003; Maccoby & Lewis, 2003). Second, the DRD4 polymorphism has been related to negative emotionality in infancy (Holmboe, Nemoda, Fearon, Sasvari-Szekely, & Johnson, 2010), thereby raising the prospect that the repeatedly chronicled and aforementioned temperament-X-child-care-quality interaction discerned by Pluess and Belsky (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2009, 2010) could be the result of a gene-X-environment (GXE) interaction involving DRD4; we evaluate this very possibility in the final analysis presented in this report.

A third and perhaps more important reason for focusing on the DRD4 polymorphism in this inquiry is that Dutch investigators have found that it moderates the effect of quality of parenting on externalizing behavior problems in both observational research (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2006) and intervention work (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, Pijlman, Mesman, & Juffer, 2008). Specifically, children carrying the 7-repeat allele proved more susceptible to parenting effects than did children not carrying this version of the gene; and they did so in a manner consistent with differential susceptibility. Because the measurements of quality of child care in the NICHD Study tap much the same caregiving behavior of child care providers as did the measures of parenting examined in these Dutch studies, it certainly is conceivable that this same polymorphism might moderate the effects of child care quality—and perhaps quantity and type of care as well—on externalizing behavior problems and social skills. This possibility would seem further buttressed by the fact that a 10-study meta-analysis revealed that variation in genes related to dopamine signaling in the brain influence children's sensitivity to both sensitive or responsive and harsh or unresponsive parenting (Bakermans-Kranenburg & van IJzendoorn, 2011).

Reasons for focusing on the serotonin transporter gene, 5-HTTPLR, as a possible moderator of child care effects in this report are much the same as those highlighted in the case of DRD4. It, too, has been specifically implicated in moderating effects of parenting on child development (e.g., Barry, Kochanska, & Philibert, 2008) and has been found to be related to negative emotionality (Auerbach et al., 1999), even moderating the effect of prenatal stress on negative emotionality in infancy (Pluess et al., 2011). In fact, a recent meta-analysis of GXE studies involving children under 18 years of age reveals 5-HTTLPR to operate as a “plasticity gene”—with carriers of short alleles disproportionately benefiting from supportive environmental conditions while also being most adversely affected by negative contextual conditions more than others (van IJzendoorn, Belsky, & Bakermans-Kranenburg, submitted).

Current Study

In sum, in this work we address, for the first time, whether effects of day care are genetically moderated, by focusing on two particular polymorphisms, DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR, and social adjustment as measured by repeated teacher reports of externalizing behavior problems and social skills across the middle-childhood years. It should be noted that the current study involves a smaller sample than used in most analyses of NICHD SECCYD data due to the fact that not all children provided DNA. Although this makes precise comparison with other NICHD SECCYD reports difficult, it is not unusual for parents to turn down the opportunity for genetic data to be collected on their children.

We further seek to determine whether any detected GXE effects prove consistent with diathesis-stress or differential-susceptibility theorizing. Additionally, we endeavor to determine whether conclusions that only quantity and type of child care, not quality of care, predict social adjustment, at least during the period from just before or at time of school entry to the end of the elementary school years, need to be modified as a result of the detection of GXE interaction involving quality of care. In so doing, we extend prior work showing that at least one child attribute, early difficult temperament, moderates the effect of child care quality on externalizing problems and social skills. Indeed, we additionally seek to determine, to our knowledge for the first time, whether a previously documented moderational effect of a feature of temperament is independent of genetic moderation that might be discerned in this inquiry. In view of the fact that previously cited research chronicles links between DRD4 and 5HTTLPR and negative emotionality (Auerbach, et al., 1999; Holmboe, et al., 2010) there are certainly grounds for predicting that a GXE effect involving one or both of these polymorphisms could account for a parallel moderational effect involving difficult temperament.

Finally, given the availability of repeated measurements of our dependent variables from just before or during the kindergarten year through sixth grade, we seek to determine whether GXE effects prove to be time limited or endure. General developmental thinking presupposes that the greater the time between when a developmental experience or exposure occurs and when its hypothesized effect is measured, the weaker will any effect of the former be on the latter. We can see no reason why this would not apply to a genetically moderated effects of early experience, in this case child care experience. Thus, we not only seek to determine whether DRD4 moderates the effect of child care around the transition to school, but whether it continues to do so through the elementary-school years. We do this by determining whether the child care-related GXE interactions under investigation predict the slope—or change—in the outcomes studied from initial time of measurement just before school entry (behavior problems) or in kindergarten (social skills) to about 12 years of age; and, if so, we then evaluate child care-related GXE effects on social functioning at subsequent measurement occasions. With the exception of two very recent studies (Petersen et al., 2012; Sulik et al., 2011), virtually all GXE work to date has focused exclusively on outcomes measured at one point in time. Thus, it is impossible to determine whether detected GXE effects dissipate, strengthen or remain unchanged over time. Unless the possibility that GXE effects change over time is evaluated, the enduring nature of any discerned GXE effect cannot be known.

Method

Participants

Families were recruited through hospital visits to mothers shortly after the birth of a child in 1991 in 10 locations in the U.S. During selected 24-hour intervals, all women giving birth (n = 8,986) were screened for eligibility. From that group, 1,364 families completed a home interview when the infant was 1-month old and became study participants. DNA (buccal cell swabs) was collected when children were 15 years old. Details of the sampling plan can be found in NICHD ECCRN (2005a).

Only children of Caucasian ethnicity were included in the present study to avoid confounding effects of ethnic differences in gene frequency. Genetic data was available for 516 of the 1097 Caucasian children. Of the 516 children with genetic data, 8 were excluded from the analysis sample due to having no outcome data, resulting in a final sample of 508 children. Children excluded, relative to those included, came from households with lower income-to-needs ratios (2.93 vs. 3.89) and with less educated (13.96 vs. 14.70 years) and more depressed (10.27 vs. 9.23) mothers, who were more likely to be single parents (20.80% vs. 9.35%) and who provided lower quality parenting (-.16 vs. .18). Excluded children were rated as having a more difficult temperament in infancy (3.21 vs. 3.13), experienced a lower proportion of center child care prior to starting school (.19% vs. .23%), had more externalizing behavior problems at every assessment from kindergarten (50.30 vs. 49.05) through sixth grade (51.05 vs. 49.32), and less social skills at every assessment from kindergarten (102.31 vs. 104.81) through sixth grade (101.23 vs. 104.50). Characteristics of the final sample and means of all variables are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Variables | N | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal education at 1 month [years] | 508 | 14.70 (2.39) |

| Income to needs ratio (across 54 months) | 507 | 3.89 (2.70) |

| Maternal depression (across 54 months) | 508 | 9.23 (6.18) |

| Parenting quality (across 54 months) | 505 | .18 (.58) |

| Partner presence (across 54 months) | 508 | 90.65 (23.16) |

| Child temperament at 6 months | 499 | 3.13 (.40) |

| Child care quality (across 54 months) | 464 | 2.82 (.24) |

| Child care hours (across 54 months) | 502 | 25.89 (16.07) |

| Center child care (across 54 months) | 495 | .23 (.28) |

| Child gender | ||

| Boy | 251 | 49.4% |

| Girls | 257 | 50.6% |

| Child DRD4 | ||

| DRD4-7R present | 135 | 26.6% |

| DRD4-7R absent | 373 | 73.4% |

| Child 5-HTTLPR | ||

| l/l | 143 | 28.1% |

| l/s | 255 | 50.2% |

| s/s | 110 | 21.7% |

| Child externalizing behavior at 54 months | 354 | 49.75 (9.53) |

| Child externalizing behavior at KG | 465 | 49.05 (8.53) |

| Child externalizing behavior at G1 | 471 | 49.76 (8.32) |

| Child externalizing behavior at G2 | 451 | 49.50 (8.26) |

| Child externalizing behavior at G3 | 471 | 50.40 (8.37) |

| Child externalizing behavior at G4 | 454 | 49.18 (8.21) |

| Child externalizing behavior at G5 | 464 | 49.78 (8.27) |

| Child externalizing behavior at G6 | 439 | 49.32 (8.91) |

| Child social skills at KG | 458 | 104.81 (13.61) |

| Child social skills at G1 | 467 | 105.06 (13.06) |

| Child social skills at G2 | 449 | 106.86 (13.45) |

| Child social skills at G3 | 467 | 103.84 (13.41) |

| Child social skills at G4 | 453 | 104.16 (13.16) |

| Child social skills at G5 | 464 | 104.23 (13.73) |

| Child social skills at G6 | 430 | 104.50 (14.08) |

Measures

With the exception of DRD4, 5HTTLPR and difficult temperament, most measures described are very similar to those used in Belsky, Vandell et al.'s (2007) first evaluation of longer-term child care effects in the NICHD Study. Additional information about procedures and measures are provided in Manuals of Operation of the study, located at http://www.nichd.nih.gov/research/supported/seccyd.cfm.

Child care Characteristics

Nonfamilial child care was defined as regular care by anyone other than the mother, father or grandparents—including nannies (whether in home or out of home), family day-care providers, and centers. Three aspects of child care experiences were measured.

Child care quantity

Parents reported children's hours of routine nonfamilial care during phone and personal interviews conducted at 3- or 4-month intervals from age 1-54 months, as well as the type(s) of child care used. The hours spent in all settings were summed for each of 17 intervals or “epochs” and parameterized on an hours-per-week basis. Individual measures of level and rate of change in quantity of care were computed as the individual intercepts and slopes from an unconditional HLM analysis of these 17 repeated measures. Following NICHD ECCRN (2003) , age was centered at the measurement midpoint, 27 months, so the estimated intercept reflected that child's hours-per-week at 27 months of age.

Child care type

For each measurement epoch, each of the child's care arrangements was classified as center, child care home (any home-based care outside the child's own home except care by grandparents), in-home care (any caregiver in the child's own home except father or grandparent), grandparent care, or father care. The proportion of epochs in which the child received care in a center for at least 10 hours per week was used to represent type of care.

Child care quality

Multiple observational assessments using the Observational Record of the Caregiving Environment (ORCE) were conducted in the primary child care arrangement at ages 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months to evaluate how sensitive, responsive, stimulating, positive and non-negative and non-intrusive caregiving proved to be; for measurement details, see NICHD ECCRN (2002). As with quantity, individual measures of level and change in quality (i.e., slope) were estimated with an unconditional HLM analysis (NICHD ECCRN, 2003).

Covariates

Early childhood

Following Belsky, Vandell et al. (2007), measures of maternal, child, and family characteristics during infancy and early childhood were collected and used as controls for possible selection bias: child gender, maternal education (years of schooling at time of child's birth); the proportion of (five measurement) epochs through 54 months in which the mother reported a husband/partner was present; family income through 54 months calculated as the mean income-to-needs ratio; and the mean of maternal depressive symptoms assessed by the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scales reported by the mother at 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months. These early childhood covariates were included in the reported HLM analyses as time-invariant controls.

Difficult temperament

Temperament was assessed by maternal report at 6 months using an adapted version of the Infant Temperament Questionnaire (Carey & McDevitt, 1978). Items were designed to capture approach, activity, intensity, mood, and adaptability. An overall summary of “difficultness” was calculated with higher values reflecting higher negative emotionality.

Parenting Quality 6-54 Months

Parenting quality was assessed by (1) maternal sensitivity in semi-structured play and (2) observation at home:

-

(1)

Maternal Sensitivity: Mother-child interactions were videotaped in semi-structured 15-minute observations at 6, 15, 24, 36, and 54 months, with interactional tasks enabling evaluation of age-appropriate qualities of maternal behavior. Videotapes were coded at a central location by raters blind to other information about the families. Inter-coder reliability was determined by assigning two coders to 19-20% of the tapes randomly drawn at each assessment period. Inter-coder reliability was calculated as the intra-class correlation coefficient. Reliability for the composite scores used in the current report exceeded .83 at every age. At 6, 15, and 24 months, composite maternal sensitivity scores were created from the sums of 3 4-point ratings (maternal sensitivity to child non-distress, intrusiveness [reversed], and positive regard). At 36 and 54 months, the maternal sensitivity composite was the sum of the three 7-point ratings of supportive presence, hostility (reversed), and respect for autonomy. Cronbach alphas exceeded .70 at every age.

-

(2)

The Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME: Caldwell & Bradley, 1984) was administered during home visits at 6, 15, 36, and 54 months. The Infant/Toddler version of the Inventory (IT-HOME), comprised of 45 was used across the first three years of life. The Early Childhood version of the Inventory (EC-HOME), comprised of 55 items, was used at 36 and 54 months. A centrally located system of training was used for data collectors at each age. Cronbach alphas for the total score at each age exceeded .77.

The HOME total and maternal sensitivity ratings were standardized and averaged at each age and then across the first 54 months to create a composite score measure of early parenting quality.

Primary-grades

Measures of family demographic and psychological characteristics also were obtained when children were in kindergarten and in 1st, 3rd, and 5th grades. Following Belsky, Vandell et al. (2007), the following were included as time-varying covariates in the HLM analyses: presence of a husband/partner in the household, income-toneeds ratio, maternal depressive symptoms and parenting quality. Composite parenting quality scores for the primary grades were created similar to parenting quality for 6-54 months (see above) by averaging standardized ratings of observed maternal sensitivity and standardized ratings of observed home environmental quality (HOME: Caldwell & Bradley, 1984) which were assessed at 54 months, 1st (only maternal sensitivity), 3rd, and 5th grade.

In addition to family-related covariates classroom quality and after-school experience during the primary grades were included as controls. Children's classroom experiences were measured using the Classroom Observation System for First Grade (Allhusen et al., 2004), for Third Grade (NICHD ECCRN, 2005b) and for Fifth Grade (NICHD ECCRN, 2004).These observations focused on the classroom as well as the specific study child and his or her classroom experiences. Three seven-point global ratings of the classroom environment were made at the end of two (1st grade) or eight (3rd & 5th grade) 44-minute observation cycles: over-control by teacher, teacher's emotional detachment, teacher's sensitivity to student needs.

Regarding after-school experience mothers were interviewed by telephone in the fall and spring of kindergarten and 1st, 3rd and 5th grades about the study children's out-of-school care. Following Belsky, Vandell et al. (2007), hours of nonparental out-of-school care arrangements (here named after-school hours) were obtained for each school year from the average across the spring and fall reports of the total hours mothers reported across all non-parental out-of-school care arrangements.

Child Outcomes

Externalizing Behavior Problems

Teachers reported on children's externalizing behavior problems (e.g., “hits others”, “disobedient at school”, “argues a lot”) repeatedly—at 54 months, kindergarten and annually in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th grades—using the Child Behavior Checklist Teacher Report Form (TRF: Achenbach, 1991). Raw scores were converted into standard T-scores, based on normative data for children of the same age.

Social Skills

Teachers reported on children's social competence and social skills (e.g., “makes friends easily”, “controls temper when arguing with other children”, “asks permission before using someone else's property” ) repeatedly using the Social Skills Questionnaire from the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS: Gresham & Elliott, 1990)— beginning at kindergarten and annually thereafter in 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th grades. For purposes of this report, raw total scores were converted into standardized scores, based on normative data for children of the same age.

Genetic Analyses

DNA was extracted from buccal cell swabs (Freeman et al., 2003). The majority of samples were genotyped twice for both DRD4 (n = 438, 86.2%) and 5-HTTLPR (n = 465, 91.5%) in order to evaluate the reliability of genotyping. If there was a discrepancy between the two assessments genotyping was repeated until the same result was found twice. We defaulted to the original genotype, however, if a sample could not be genotyped a second time or if we were unable to identify a single genotype for a given sample.

DRD4 was identified using a modified assay based on methods developed by Sander et al. (1997) and modified by Anchordoquy et al., (2003): 1 × Taq Gold Buffer, 2.25 mM final concentration of MgCl2, 10% DMSO, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.1 mM deazo GTP, 0.75 uM primers, 40 ng of DNA and 1 U of Taq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) in a volume of 12 microliters. The primer sequences were: 5’-6-FAM-GCGAC TACGTGGTCTACTCG-3’ and reverse, 5’-AGGACCCTCATGGCCTTG-3’. The amplification procedure was as described by Anchordoquy et al (2003). One microliter was removed and placed in a 96 well plate and 10 microliters of formamide containing LIZ-500 standard (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). The plate was run using a Fragment Analysis protocol in the 3730XL DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA). Fragments were analyzed using Genemapper software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) with PCR products of (in bp): 379, 427, 475 (43), 523, 571, 619 (73), 667, 715, 763, and 811. DRD4 was coded as individuals carrying one or more 7-repeat allele versus all others. Agreement between first and second genotyping was 86.5% (κ = .63, p < .001). For the 13.5% where the two rounds of genotyping proved discrepant, a third round was conducted which determined what genotype these discrepant cases would be assigned. The DRD4 7-repeat allele was present in 26.6% of the final sample.

5-HTTLPR was identified using a modified assay based on the method of Lesch et al. (1996) and Anchordoquy et al (2003): 1 x Taq Gold Buffer, 1.8 mM final concentration of MgCl2, 10% DMSO, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.1 mM deazo GTP, 0.6 uM primers, 40 ng of DNA and 1 U of Taq Gold (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) in a volume of 15 microliters. The primer sequences were: forward, 5’-VIC- GGCGTTGCCGCTCTGAATGC-3’ and reverse, 5’-GAGGGACTGAGCTGGACAACCAC-3’. The same amplification protocol was used as for DRD4 (see above). Fragments were analyzed using Genemapper software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City CA) with PCR products of 484 or 528 bp. Agreement between first and second genotyping was 83.7% (κ = .74, p < .001). For the 16.3% where the two rounds of genotyping proved discrepant, a third round was conducted which determined what genotype these discrepant cases would be assigned. Genotype distribution in the final sample (l/l: 28.1%; l/s: 50.2%; s/s: 21.7%) conformed to the Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (p = .98).

Data Analysis Plan

Data analysis focused on testing the moderating effect of DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR on the long-term associations between child care experiences during the first 4.5 years and children's externalizing behavior from that age through spring of 6th grade and children's social skills from kindergarten through spring of 6th grade. An analytic strategy similar to that used Belsky, Vandell et al. (2007) and Pluess and Belsky (2010) was implemented. Hierarchical linear models (HLM: Bryk & Raudenbush, 2002; Singer & Willett, 2003) were fitted to estimate individual and group linear and quadratic growth curves. The models included family and child care or school experiences measured during both the preschool (i.e., 0 – 54 months) and primary-school years (i.e., 54 months – 6th grade) as covariates, as well as child DRD4, 5-HTTLPR and the 2-way interactions involving each polymorphism and each of the three child care variables (i.e., quality, quantity or hours and center-care experience). Separate models were run to test each possible 2-way interaction term between each gene and each child care variable on both outcomes of interest, yielding a total of 12 separate models. Individual intercepts and linear slopes with respect to age were estimated as correlated random effects for each child. In the interest of space, reporting of results focuses exclusively upon the interactions between DRD4 and early-child care experiences, that is, those effects which extend previous findings (Belsky, Vandell, et al., 2007; Pluess & Belsky, 2010), are of primary interest here, and proved statistically significant.

Several modelling decisions were made. First, age was centered at 54 months for externalizing problems and at kindergarten for social skills, as these were the initial occasions at which the problem-behavior and social-skills measures which were repeatedly administered were obtained. Perhaps noteworthy, then, is the fact that these first measurements of the two constructs were provided by different respondents—child care caregivers at 54 months in the case of behavior problems and kindergarten teachers in the case of social skills. The initial interaction-effect coefficients to be presented indicate whether the GXE interactions of interest were related to (a) behavior problems at the age of 54 months or social skills at kindergarten and (b) change—or slope—of externalizing behavior from 54 months to 6th grade or of social skills from kindergarten to 6th grade. If any interaction term predicted the slope, the initial analysis was re-run repeatedly after changing the intercept age so that the changing nature over time of the interaction between the polymorphism and child care factor in question could be illuminated.

Whenever GXE interactions predicting an intercept proved significant, we conducted a “regions of significance” analysis, following Kochanska and associates (2011), to evaluate whether the significant interaction proved more consistent with a diathesis-stress or differential-susceptibility model of environmental action. The region of significance defines the specific values of a child care feature (i.e., quality, quantity, type) at which the slope between a particular polymorphism and externalizing problems moves from significance to non-significance and/or vice-versa (Aiken & West, 1991; Hayes & Matthes, 2009; Preacher, Curran, & Bauer, 2006). If and when evidence emerged from the regions-of-significance analysis that the data conformed to a differential-susceptibility model of environmental action, we doubled checked this conclusion by implementing a series of additional and more demanding analytic steps recently outlined by Roisman and associates (2012) for evaluating the nature of the interaction detected.

Missing data occurred in the included sample (n = 508) due to attrition and failure to complete all assessments, as follows with respect to the primary child care predictors and child-development outcomes: quality of care (8.7%), hours of care (1.2%), center-care experience (2.6%), externalizing behavior (7.3% to 30.3%, representing lowest and highest at any one time across repeated measurement occasions), and social skills (8.1% to 15.4%). Missing data also occurred in primary-grade covariates, as follows: parenting quality (.6% to 5.9%), maternal depression (1.0% to 6.9%), income (3.0% to 8.7%), partner presence (0.2% to 5.5%), classroom quality (3.7% to 20.9%), and after school activities (1.6% to 5.3%). Missing data of the included sample were imputed with multiple imputation (Schafer, 1997) using all available data (N = 1364). Test statistics and regression coefficients were averaged across five imputed datasets. When analyses were run with only cases with complete data, results did not differ from those derived from the imputed data sets. For the simple-slopes and regions-of-significance follow-up analyses, intercepts for externalizing behavior and social skills were estimated by means of HLM analyses. These intercepts were then averaged across the five imputed data sets. The level of significance for all analyses was set at α = .05.

Results

Four sets of results are presented, the first preliminary, provides simple descriptive statistics on the measurements included in this report, while illuminating the most important bivariate relations among variables; the second primary, addressing the interactions of interest between DRD4 or 5-HTTLPR and child care experiences in the prediction of children's externalizing behavior and social skills over time; the third, follow-up analyses illuminating the form of significant interactions; and a fourth set evaluating whether the detected gene-x-environment interactions remained significant when a previously chronicled interaction involving child care and difficult temperament was taken into account (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2009, 2010).

Preliminary Analysis: Descriptive Statistics and Unadjusted Associations

Table 1 presents the means and SDs of the variables of primary interest. With respect to the intercorrelation of these measurements, perhaps what is most important to note is that DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR were not significantly associated with child care predictors nor the child-development outcome variables except as follows: DRD4 with 6th-grade externalizing behavior (r = -.10, p < .05) and 5-HTTLPR with 5th-grade externalizing behavior (r = -.09, p < .05) and social skills (r = .10, p < .05). Given the lack of significant associations between genes and outcomes at all other assessment points, the data appear to fulfil the criteria of independence of the moderator variable (i.e., DRD4, 5-HTTLPR) from the environment (i.e. child care) and outcome (i.e., externalizing problems, social skills), thereby generally meeting criteria for testing differential susceptibility (Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, et al., 2007). Externalizing behavior and social skills were significantly and negatively associated at all assessments (range r: -.13 to -.60, p < .01).

Primary Analyses

For the primary analyses predicting, first, externalizing behavior and, second, social skills, we ran hierarchical linear models across the multiple assessment points. Variables included child DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR, child care quality intercept (estimated quality of care at 27 months, reflecting the midpoint between 6 and 54 months), the hours-per-week intercept (estimated from HLM analyses in which the intercept was set at 27 months), proportion of 3-4 month epochs in center-based child care for at least 10 hours per week, six preschool time-invariant covariates (child gender, infant temperament at 6 months, maternal education at month 1, mean income-to-needs ratio between 1 and 54 months, mean parentingquality between 6 and 54 months, mean maternal depressive symptoms between 6 and 54 months), and five concurrent time-varying covariates from 54 months through 6th grade (income-to-needs ratio, parenting quality, maternal depression, observed school classroom quality, and hours-per-week of after-school care (set to 0 for 54 months). The model was run once including only the covariates, child care variables, and the two polymorphisms, all as main effects, and then again with 2-way interactions involving DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR with each of the three child care variables (i.e. six separate models for each outcome). Because 5-HTTLPR did not significantly predict the intercept or slope of either externalizing behavior or social skills, whether as a main effect or in interaction with any of the child care variables, reporting below pertaining to genetic findings is restricted to those involving DRD4; Tables 2 and 3 present results for externalizing problems and social skills, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of Hierarchical Linear Model Predicting Behavior Problems (N = 508)

| Behavior problems intercept centered at 54M | Behavior problems slope | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | B | B | |

| Step 1 | |||

| Maternal education at 1 month | .06 | −.04 | |

| Income to needs ratio (across 54 months) | .18 | −.05 | |

| Maternal depression (across 54 months) | −.03 | < −.01 | |

| Parenting quality (across 54 months) | −2.63** | .03 | |

| Partner presence (across 54 months) | −.05** | < .01 | |

| Child temperament at 6 months | −.17 | −.18 | |

| Child gender (1=male; 2=female) | −.02 | .02 | |

| Child care quality (across 54 months) | .02 | .37 | |

| Child care hours (across 54 months) | .08** | −.01** | |

| Center child care (across 54 months) | 4.00** | −.28 | |

| Child DRD4 (0=7R absent; 1=7R present) | .59 | −.21 | |

| Child 5-HTTLPR (0=l/l; 1=l/s; 2=s/s) | −.15 | −.18 | |

| Step 2 | |||

| DRD4 X child care quality | −6.23* | .96# | |

| DRD4 X child care hours | .07 | −.02* | |

| DRD4 X center child care | 2.66 | −.97* |

Note. The model included the following time variant covariates from 54 months through 6th grade which are not displayed in the table: income to needs ratio, maternal depression, parenting quality, partner presence, classroom quality, after school activities. The displayed coefficients of the variables at step1 represent the values before inclusion of interaction terms at step2.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Summary of Hierarchical Linear Model Predicting Social Skills (N = 508)

| Social skills intercept centered at kindergarten | Social skills slope | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variables | B | B | |

| Step 1 | |||

| Maternal education at 1 month | .49# | −.04 | |

| Income to needs ratio (across 54 months) | −.15 | .08 | |

| Maternal depression (across 54 months) | .03 | < .01 | |

| Parenting quality (across 54 months) | 3.60* | .03 | |

| Partner presence (across 54 months) | .06* | < .01 | |

| Child temperament at 6 Months | .81 | .15 | |

| Child gender (1=Male; 2=Female) | 1.34 | −.40# | |

| Child care quality (across 54 months) | 1.85 | −.12 | |

| Child care hours (across 54 months) | −.04 | .01 | |

| Center child care (across 54 months) | −3.25 | .73 | |

| Child DRD4 (0=7R absent; 1=7R present) | −.46 | .18 | |

| Child 5-HTTLPR (0=l/l; 1=l/s; 2=s/s) | −.02 | .13 | |

| Step 2 | |||

| DRD4 X child care quality | 10.67* | −2.48* | |

| DRD4 X Child Care Hours | −.01 | <.02 | |

| DRD4 X Center Child Care | 5.45 | −.82 |

Note. The model included the following time variant covariates from Kindergarten through 6th grade which are not displayed in the table: income to needs ratio, maternal depression, parenting quality, partner presence, classroom quality, after school activities. The displayed coefficients of the variables at step1 represent the values before inclusion of interaction terms at step2.

p < .10.

p < .05.

** p < .01.

Externalizing Behavior

With regard to main effects, findings displayed in Table 2 indicate that externalizing problems at 54 months were significantly greater when parenting quality across the early years was lower, when children lived in a single-parent home (i.e., less partner presence), when children were exposed to higher proportions of center care, and when they spent more hours in child care irrespective of type of care. The amount of time spent in child care also significantly predicted the decline in externalizing behavior across the primary grade years. None of the time variant primary-grade covariates significantly predicted the intercept or slope of externalizing behavior problems except after-school experience, which predicted both the intercept (B = -.06, 95% CI of B = -.12 to -.003, p = .04) and the slope (B = .03, 95% CI of B = .01 to .05, p < .01). Notably, neither DRD4 nor child care quality significantly predicted problem behavior (intercept or slope) as main effects.

DRD4 and child care quality did interact, however, to significantly predict externalizing behavior centered at 54 months (B = -6.23, 95% CI of B = -12.26 to -.21, p = .04) and to marginally predict the slope of externalizing behavior across the eight assessment points (B = .96, 95% CI of B = -.11 to 2.03, p = .08). The latter result was followed up below to determine whether the GXE in question remained significant at times of measurement after age 54 months. The slope of externalizing problems was also significantly predicted by interactions involving DRD4 and child care hours (B = -.02, 95% CI of B = -.04 to -.003, p = .02) and child care type (B = -.97, 95% CI of B = -1.88 to -.06, p = .04); but because follow-up analyses never revealed significant relations between these interactions and externalizing intercepts at any of the ages of measurement, in the interests of space details of such analyses are not reported.

Social Skills

Results pertaining to main effects indicated that social skills at kindergarten were significantly greater when parenting quality across the early years was higher and when children did not live in a single-parent home (i.e., more partner presence). None of the time variant primary-grades’ covariates significantly predicted the intercept or slope of social skills except after-school experience which predicted the slope (B = -.04, 95% CI of B = -.08 to -.005, p = .02). Notably, neither DRD4 nor any of the child care variables predicted the social skills intercept at kindergarten as main effects.

DRD4 and child care quality did interact, however, to predict social skills centered at kindergarten (B = 10.67, 95% CI of B = 1.23 to 20.11, p = .03) and the slope of social skills across the eight assessment points (B = -2.48, 95% CI of B = -4.52 to -.44, p = .02). The latter result was followed up below to determine whether the GXE in question remained significant at times of measurement after kindergarten.

Secondary and Tertiary Analyses: Form and Timing of GXE Interaction

Two sets of follow-up analyses were carried out to illuminate the significant DRD4-X-child care-quality interactions, one pertaining to the form of the interaction and the other to its potentially changing nature over time.

Interaction Form

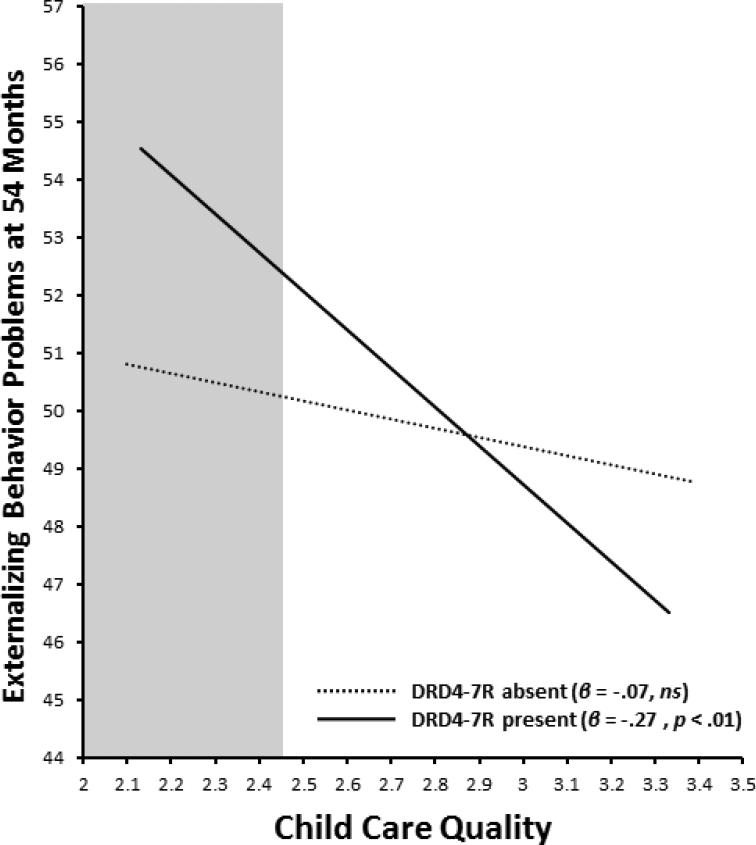

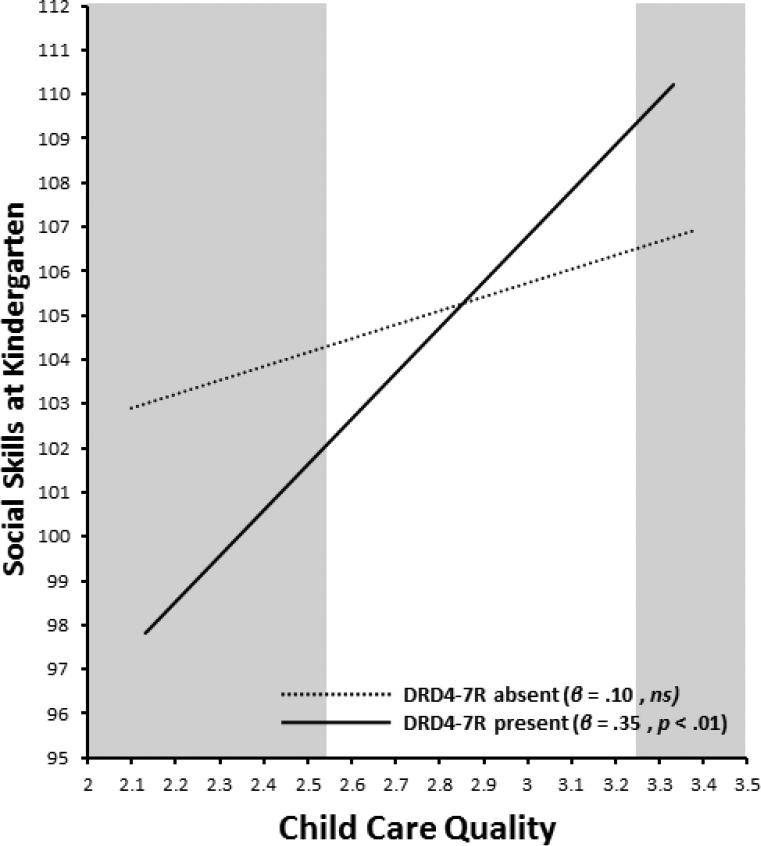

In order to interpret the significant DRD4-X-quality interaction in predicting the externalizing-behavior intercept at 54 months and the social-skills intercept at kindergarten, we plotted regression slopes of child care quality on predicted externalizing problems at 54 months and social skills at kindergarten, separately for children with and without the DRD4 7-repeat allele. Figure 1 indicates that the relation between child care-quality and externalizing problems was negative and significant in the case of children carrying the DRD4 7-repeat allele (β = -.27, p < .01), but not in the case of children without the DRD4 7- repeat (β = -.07, p = .21); and Figure 2 indicates that the relation between child care quality and social skills was positive and significant in the case of children carrying the DRD4 7-repeat allele (β = .35, p < .01), but not in the case of children without the DRD4 7-repeat (β = .10, p > .05)

Figure 1.

Child care quality by DRD4 interaction predicting teacher reported externalizing problems at 54 months. The shaded area represents the region of significance.

Figure 2.

Child care quality by DRD4 interaction predicting teacher reported social skills at Kindergarten. The shaded area represents the region of significance.

Visual inspection of Figures 1 and 2 reveal a cross-over interaction consistent with differential susceptibility in that children carrying the DRD4 7-repeat allele had the most externalizing problems when exposed to low-quality child care early in life yet the least such problems when quality was high, as well as the most social skills when quality was high and the least when quality was low. Analysis of regions of significance of the data on which Figure 1 is based, using a tool provided by Preacher et al. (2006), yielded only a lower bound of significance within the observed range of child care quality, however; that is, the slope between DRD4 and externalizing problems proved significant when child care quality was lower than 2.45 (i.e., shaded areas in Figure 1), representing 6.5% of the sample, with no significant differences emerging above this value. Analysis of the data on which Figure 2 is based, on the other hand, yielded both a lower and a higher bound of significance within the observed range of child care quality; more specifically, the slope between DRD4 and social skills proved significant when child care quality was lower than 2.53, representing 9.3% of the sample, and higher than 3.24, representing 2.2% of the sample (i.e., shaded areas in Figure 2). Consequently, the significant interaction between DRD4 and child care quality in the prediction of externalizing problems at 54 months was more consistent with a diathesis-stress model of environmental action, whereas the significant interaction between DRD4 and social skills at kindergarten was more consistent with a differential-susceptibility model.

Before confidently embracing a differential-susceptibility conclusion with respect to social skills at kindergarten, we proceeded to implement a series of additional analyses which Roisman and associates (2012) have proposed for evaluating differential susceptibility (using an internet tool: http://www.yourpersonality.net/interaction/ros2.pl). According to these additional analyses the cross-over point of the simple slopes on childcare quality was at 2.85, well within their criterion range of +/- 2 standard deviations (SD = .23) from the mean (M = 2.82). The proportion of the interaction (PoI) provides a way to express the proportion of the total interaction that is represented below and above the cross-over point, with PoI's close to .50 regarded by Roisman et al. (2012) as strong evidence differential susceptibility. PoI in the +/- 2 SD range with respect to social skills at kindergarten was .57 below and .43 above the crossover point, clearly close to the .50 criteria. The proportion affected (PA) index represents the proportion of cases that fall above the cross-over point with larger percentages suggesting stronger evidence for differential susceptibility relative to diathesis stress. PA with respect to social skills was .49. Hence, these additional analyses suggest that the interaction between child care quality and DRD4 in the prediction of social skills does reflect a differential-susceptibility rather than a diathesis-stress pattern of environmental action, consistent with the visual interpretation of the regions of significance analysis.

GXE Interaction Over Time

In order to illuminate the nature of the significant interaction between DRD4 and child care quality in predicting the slope of behavior problems and of social skills, we ran, respectively, six or seven additional HLM models, each centered at a different assessment point (externalizing: kindergarten and 1st through 6th grade; social skills: 1st through 6th grade ). After being significant at 54 months (see above), the interaction between DRD4 and child care quality in the prediction of behavior problems proved marginally significant at kindergarten (B = -5.35, 95% CI of B = -10.83 to .13, p = .06) and non-significant thereafter (B = -4.00 to .68, p > .10 for all). Similarly, after being significant at kindergarten (see above), the interaction between DRD4 and child care quality in the prediction of social skills proved marginally significant at 1st grade (B = 7.45, 95% CI of B = -.56 to 15.46, p = .07) and non-significant thereafter (B = 4.89 to -4.90, p > .10 for all). In both cases, then, the data suggest that the genetic moderation of effects of early child care quality on children's social-emotional adjustment dissipated over time.

Including Child Care-Quality-X-Difficult-Temperament Interaction

Recall that in earlier analyses of NICHD Study data we discerned significant interactions between infant temperament and child care quality in predicting behavior problems and social skills (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2009, 2010). Given the aforementioned evidence indicating that DRD4 is related to infant negative emotionality (Holmboe, et al., 2010; Ivorra et al., 2010), we sought to determine whether the DRD4-X-child care-quality interactions reported herein were a function of the previously detected temperament-X-child care-quality interaction effects. Thus, we reran the two HLM models with the significant interaction term between DRD4 and child care quality predicting (1) externalizing behavior problems at 54 months and (2) social skills at kindergarten with an additional 2-way interaction term involving difficult infant temperament and child care quality added to the model (along with the main effect of temperament). Consistent with earlier findings (Belsky & Pluess, 2012; Pluess & Belsky, 2009, 2010), the interaction between temperament and child care quality predicting the 54-month problem-behavior intercept proved significant (B = -10.68, 95% CI of B = -17.79 to -3.57, p < .01), while the GXE interaction between DRD4 and child care quality remained marginally significant (B = -5.50, 95% CI of B = -11.48 to .47, p = .07). Similarly, the interaction between temperament and child care quality predicting the kindergarten social-skills intercept proved marginally significant (B = 10.82, 95% CI of B = -1.04 to 22.69, p = .07), whereas the GXE interaction between DRD4 and child care quality remained significant (B = 9.96, 95% CI of B = .51 to 19.41, p = .04). These findings suggest that that the moderating effects of infant temperament and DRD4 vis-à-vis child care quality and its effects on problem behavior and social skills are largely, even if not entirely, independent.

Discussion

The research reported herein had multiple goals, each of which is considered in turn before turning to study limitations.

GXE Interaction and Its Form

In this first study investigating whether effects of day care on children's social adjustment across the childhood years—reflected in their externalizing problems and social skills—might be genetically moderated, evidence emerged that this was indeed the case, but only with regard to DRD4, not 5-HTTLPR, and quality of care. Recall that DRD4 and 5-HTTLPR were selected for inclusion in this research because it is these two polymorphisms for which the most GXE evidence has emerged seemingly consistent with differential susceptibility. It should be appreciated, however, that this could itself be an artefact of these two polymorphisms being among the most studied from a GXE perspective. It was somewhat surprising that no significant GXE interactions emerged in the case of 5-HTTLPR given the results of a recent meta-analysis evaluating—and documenting—such effects in the case of children under 18 years of age; indeed, it provided evidence of GXE consistent with differential susceptibility (van IJzendoorn, et al., submitted). It did not include, however, any research evaluating child care effects.

With regard to the GXE effects detected, these involved DRD4 and quality of care predicting externalizing problems at 54 months and kindergarten and social skills at kindergarten and first grade. One of the things that makes such findings noteworthy is that different respondents provided evaluations of child behavior across the years of measurement covered in this inquiry: caregivers at 54 months, kindergarten teachers during the first year of school, first-grade teachers during the second and so on and so forth through sixth grade.

The graphical plotting of the detected GXE interactions highlighting a cross-over-interaction pattern appeared more consistent with differential-susceptibility rather than diathesis-stress thinking. The regions-of-significance analysis indicated otherwise, however, in the case of externalizing problems. Recall that it was only at low levels of quality of care that differences between children with and without the 7-repeat allele manifested themselves, with those carrying the allele appearing more adversely affected by low quality care (i.e., manifesting more behavior problems), at least during the first two years that each outcome was measured, than those not carrying this allele. The fact that the regions-of-significance analysis also revealed that children carrying the 7-repeat allele who were exposed to higher quality care benefited more than other children from such supportive environments when the outcome to be explained was social skills proved consistent with the differential-susceptibility hypothesis. That is, there was evidence of both “for-better-and-for-worse” effects of child care quality on children carrying the 7-repeat allele.

Of note, however, is that the percentage of children exposed to quality of care at a level that yielded a reliable developmental benefit—as revealed by the regions-of-significance analysis (see Figure 2)—was relatively small (2.2 %), clearly raising questions about just how strong was the “for better” side of the differential-susceptibility equation in this instance. Nevertheless, when the cross-over interaction indicative of differential susceptibility was evaluated further by applying Roisman et al.'s (2012) evidentiary standards, the data continued to highlight the differential-susceptibility nature of the interaction under consideration.

Beyond Main Effects

On the basis of the findings just summarized, it would seem that prior analyses by the NICHD ECCRN of child care effects and, in particular, quality-of-care effects on social adjustment from 54 months through sixth grade failed to detect any such effects because the original of investigators only focused on main effects or effects moderated by child gender and family risk conditions (Belsky, Vandell, et al., 2007; NICHD ECCRN, 2003). Apparently—given the non-experimental nature of the NICHD Study—low quality child care does matter with respect to problem behavior and social skills around the time of the transition to school, but only for some children, not others, with the same perhaps being true of high quality care in the case of social skills. If such findings can be replicated, they would call into question the widespread presumption that poor quality of care compromises the development of most children, at least with respect to socioemotional functioning, and that good quality care yields measureable benefits in this realm of functioning for most children. But even if this proves to be the case in future work, it would not provide grounds for reducing investment in quality of child care. Not only does the NICHD Study and many others consistently find quality of care to (modestly) predict cognitive and language development (NICHD ECCRN, 2006), as well as academic achievement (Belsky, Vandell, et al., 2007; Vandell, et al., 2010), but humanitarian considerations alone dictate the provision of good quality care conditions for all children.

The Moderating Effect of Difficult Temperament

Because previous analyses of NICHD Study data indicated that quality effects on problem behavior or social skills were moderated by difficult infant temperament, with infants scoring high in negativity proving more susceptible—for better-and-for-worse—to the apparent influence of child care quality than other infants, the issue arose as to whether the GXE interactions discerned in this inquiry involving DRD4 could underlie—and account for—the parallel interactions involving temperament reported by Pluess and Belsky (2009, 2010). As it turned out, this did not prove to be the case. Recall that in the final set of analyses presented, both interactions involving quality of care proved significant or marginally so. This means that (a) infants with difficult temperaments or (2) children carrying the 7-repeat DRD4 allele are disproportionately, even exclusively, susceptible to effects of low quality care on externalizing problem behavior and social skills around the transition to school.

To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration in a single inquiry of independent interactions involving temperament and genetics with the same (or even a different) environmental factor. There would seem to be reason to question, then, any conceptual privilege granted genes over temperament (or physiology, Boyce & Ellis, 2005) when it comes to considering organismic factors that might moderate environmental effects on human development, either in diathesis-stress or differential-susceptibility terms. It should be acknowledged, nevertheless, that results pertaining to the issue of overlap between interactions between child care quality and temperament and DRD4 on which this conclusion is based might have been different had other measures of temperament, perhaps ones based on observations rather than maternal reports, been subject to analysis. Only future research will be in position to address this possibility.

Developmental Analysis

Besides focusing on the genetic moderation of child care effects and distinguishing differential-susceptibility from diathesis-stress models of environmental action, one of the strengths of the current inquiry was that it was developmental in character. Because externalizing problems and social skills were repeatedly measured—by independent evaluators (i.e., different teachers each academic year)—we were in position not just to determine whether child care effects were moderated by the child's genetic make-up at some point in time, but whether the GXE effect initially detected in problem behavior at 54 months and in social skills at kindergarten endured, dissipated or even strengthened over time. This we could do by predicting in the initial model the slope of externalizing problem over time, that is, change in externalizing problems, and then shifting the intercept predicted in subsequent rounds of analysis from 54 months to kindergarten to first grade all the way through sixth grade.

As it turned out, the GXE interactions proved significant at the initial occasion at which the outcome was measured, but not thereafter. This seems likely to have been the result of experiences—in the family, at school, and in after-school programs perhaps—that intervened between when child care experiences and later assessments of child functioning were obtained. Clearly development is not over by the time children start school.

This observation highlights the need to avoid the implicit presumption that a GXE interaction (of any kind) detected at one point in time, as is the typical practice in most GXE inquiry, necessarily endures over time. At the same time, investigators should be alert to the possibility, not discerned in this inquiry, that a failure to detect such an interaction at one point in time does not automatically imply that it could not emerge subsequently. Only by considering functioning at multiple points in time and examining GXE effects on slope or change over time in a developmental outcome of interest will it be possible to address these matters.

Study Limitations

Perhaps the two biggest limitations of the current inquiry are that it was non-experimental in nature and included only 508 of some 1364 children initially enrolled in the NICHD Study. The observational character of this investigation clearly limits any and all causal inferences that can be drawn from the findings presented. Nevertheless, language pertaining to child care “effects” was employed throughout this report for heuristic purposes. A further, yet minor, limitation is that the study did not genotype SNP rs25531and differentiate between LA and LG alleles, and thus we were not positioned to treat the LG alleles as short alleles (Hu et al., 2006). One can also wonder whether, had the genotyping proven more reliable, more evidence of GXE interactions might have emerged, especially after the initial time of outcome measurements, or whether they might have proven more consistent with differential susceptibility rather than diathesis stress. With regard to the latter, it also seems possible that greater inclusion of exceptionally high quality child care experiences might have resulted in findings more consistent with differential susceptibility.

The limited number of research participants included in this research was mostly due to the fact that not all families agreed to contribute DNA on their child; and that two of the 10 participating research cites could not secure ethics’ approval to request DNA from study participants’ families. There was also a need, based on racial differences in gene frequencies, to keep the sample racially homogenous. Due to the consequential substantial reduction in sample size, it is difficult to be sure that the results presented herein would generalize to the original sample, to say nothing of a nationally—or internationally—representative one. Especially important in this regard is that the NICHD Study children not included in this inquiry differed from those who were included in terms of their child care experience and their social functioning.

In some sense, then, the results of this study should be regarded more as “proof of concept” rather than a basis for definitive conclusions. Results suggest that at least some child care effects may vary across children as a result of their genetic make-up. They further provide evidence that GXE effects detected at one point in time may or may not endure over time. They additionally indicate that moderational effects involving temperament or any other child characteristic should not be presumed to reflect some underlying genetic factor, at least not without evidence that the moderating effect of a temperamental factor is accounted for by the moderating effect of a genetic one.

Acknowledgements

The research described herein was supported by a cooperative agreement with the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; U10-HD25420). This paper was the result of a collaboration of the two named authors using data collected under the direction of the NICHD network authors that has been placed in the public domain. The NICHD network of authors merits our appreciation for insuring that these data were gathered and made available to all network authors and others who received permission to conduct scientific studies using them. The NICHD network authors, however, have no responsibility for how we have analyzed the data, the results we report, and the conclusions we draw. Special thanks is extended to Glenn Roisman for his herculean efforts in overseeing the genotyping of the sample.

Contributor Information

Jay Belsky, Human and Community Development University of California, Davis King Abdulaziz University Birkbeck University of London.

Michael Pluess, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London.

References

- Achenbach T. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Author; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allhusen V, Belsky J, Booth-LaForce CL, Bradley R, Brownwell CA, Burchinal M, et al. Does class size in first grade relate to children's academic and social performance or observed classroom processes? Dev Psychol. 2004;40(5):651–664. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anchordoquy HC, McGeary C, Liu L, Krauter KS, Smolen A. Genotyping of three candidate genes after whole-genome preamplification of DNA collected from buccal cells. Behavior Genetics. 2003;33(1):73–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1021007701808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auerbach J, Geller V, Lezer S, Shinwell E, Belmaker RH, Levine J, et al. Dopamine D4 receptor (D4DR) and serotonin transporter promoter (5-HTTLPR) polymorphisms in the determination of temperament in 2-month-old infants. Molecular Psychiatry. 1999;4(4):369–373. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Gene-environment interaction of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) and observed maternal insensitivity predicting externalizing behavior in preschoolers. Dev Psychobiol. 2006;48(5):406–409. doi: 10.1002/dev.20152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to rearing environment depending on dopamine-related genes: new evidence and a meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(1):39–52. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Pijlman FT, Mesman J, Juffer F. Experimental evidence for differential susceptibility: dopamine D4 receptor polymorphism (DRD4 VNTR) moderates intervention effects on toddlers' externalizing behavior in a randomized controlled trial. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(1):293–300. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RA, Kochanska G, Philibert RA. G x E interaction in the organization of attachment: mothers' responsiveness as a moderator of children's genotypes. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(12):1313–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver KM, Wright JP, DeLisi M, Walsh A, Vaughn MG, Boisvert D, et al. A gene x gene interaction between DRD2 and DRD4 is associated with conduct disorder and antisocial behavior in males. Behavioral and Brain Functions. 2007;3:30. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Infant day care: A cause for concern? Zero to Three. 1986;7(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The “effects” of infant day care reconsidered. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 1988;3:235–272. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Parental and nonparental care and children’s socioemotional development: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52:885–903. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential Susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16(6):300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Jonassaint C, Pluess M, Stanton M, Brummett B, Williams R. Vulnerability genes or plasticity genes? Molecular Psychiatry. 2009;14:746–754. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond Diathesis-Stress: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Differential susceptibility to long-term effects of quality of child care on externalizing behavior in adolescence? International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2012;36(1):2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Vandell DL, Burchinal M, Clarke-Stewart KA, McCartney K, Owen MT. Are there long-term effects of early child care? Child Dev. 2007;78(2):681–701. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Dev Psychopathol. 2005;17(2):271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell B, Bradley RH. Home observation for measurement of the environment. University of Arkansas Press; Little Rock: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Carey WB, McDevitt SC. Revision of the Infant Temperament Questionnaire. Pediatrics. 1978;61(5):735–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Hariri AR, Holmes A, Uher R, Moffitt TE. Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(5):509–527. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, McClay J, Moffitt TE, Mill J, Martin J, Craig IW, et al. Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children. Science. 2002;297(5582):851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1072290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Gene-environment interactions in psychiatry: joining forces with neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(7):583–590. doi: 10.1038/nrn1925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301(5631):386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke-Stewart KA. Infant day care. Maligned or malignant? American Psychologist. 1989;44(2):266–273. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockenberg SC. Rescuing the Baby From the Bathwater: How Gender and Temperament (May) Influence How Child Care Affects Child Development. Child Development. 2003;74(4):1034–1038. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan LE, Keller MC. A Critical Review of the First 10 Years of Candidate Gene-by-Environment Interaction Research in Psychiatry. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168(10):1041–1049. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to the environment: an evolutionary--neurodevelopmental theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23(1):7–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, Fein G, editors. Infant day care: The current debate. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman B, Smith N, Curtis C, Huckett L, Mill J, Craig IW. DNA from buccal swabs recruited by mail: evaluation of storage effects on long-term stability and suitability for multiplex polymerase chain reaction genotyping. Behavior Genetics. 2003;33(1):67–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1021055617738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham F, Elliott S. ocial skills rating system. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Matthes J. Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41(3):924–936. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.3.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmboe K, Nemoda Z, Fearon RM, Sasvari-Szekely M, Johnson MH. Dopamine D4 receptor and serotonin transporter gene effects on the longitudinal development of infant temperament. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Relations between early child care and schooling. Developmental Psychology. 1988;24:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Hu XZ, Lipsky RH, Zhu G, Akhtar LA, Taubman J, Greenberg BD, et al. Serotonin transporter promoter gain-of-function genotypes are linked to obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78(5):815–826. doi: 10.1086/503850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivorra JL, Sanjuan J, Jover M, Carot JM, Frutos R, Molto MD. Gene-environment interaction of child temperament. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31(7):545–554. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181ee4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karen R. Becoming Attached: First Relationships and How They Shape Our Capacity to Love. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Karg K, Burmeister M, Shedden K, Sen S. The serotonin transporter promoter variant (5-HTTLPR), stress, and depression meta-analysis revisited: evidence of genetic moderation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(5):444–454. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, Barry RA, Philibert RA. Children's genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children's competence: Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:605–616. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois JH, Liben LS. Child care research: An editorial perspective. Child Development. 2003;74:969–1226. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, et al. Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science. 1996;274(5292):1527–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5292.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, Lewis CC. Less day care or different day care? Child Development. 2003;74:1069–1075. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Early child care and children's development prior to school entry: Results from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. American Educational Research Journal. 2002;39(1):133–164. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Does quality of child care affect child outcomes at age 4 1/2? Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):451–469. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network COS qualitative scales and reliabilities observational ratings of the fifth grade classroom. [March 15, 2005];Child Care Data Report 571. 2004 from https://secc.rti.org/project/display.cfm?t=c&i=ccdr571.

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network . Child Care and Child Development: Results of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Guilford Press; New York: 2005a. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network A Day in Third Grade: A Large-Scale Study of Classroom Quality and Teacher and Student Behavior. The Elementary School Journal. 2005b;105(3):305–323. [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Child-care effect sizes for the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. Am Psychol. 2006;61(2):99–116. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.2.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]