Abstract

The 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification emphasizes the prognostic significance of histologic subtypes. However, one limitation of this classification is that the highest percentage of patients (~40%) is classified as acinar predominant tumors, and these patients display a spectrum of favorable and unfavorable clinical behaviors. We investigated whether the cribriform pattern can further stratify prognosis by histologic subtype. Tumor slides from 1038 patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma (1995–2009) were reviewed. Tumors were classified according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification. The percentage of cribriform pattern was recorded, and the cribriform predominant subtype was considered as a subtype for analysis. The log-rank test was used to analyze the association between histologic variables and recurrence-free probability. The 5-year recurrence-free probability for patients with cribriform predominant tumors (n=46) wasa 70%. The recurrence-free probability for patients with cribriform predominant tumors was significantly lower than that for patients with acinar (5-year recurrence-free probability, 87%; P=0.002) or papillary predominant tumors (83%; P=0.020) but was comparable to that for patients with micropapillary (P=0.34) or solid predominant tumors (P=0.56). The recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥10% cribriform pattern tumors (n=214) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 73%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern tumors (n=824; 84%; P<0.001). In multivariate analysis, patients with acinar predominant tumors with ≥10% cribriform pattern remained at significantly increased risk of recurrence, compared with those with <10% cribriform pattern (P=0.042). Cribriform predominant tumors should be considered a distinct subtype with a high risk of recurrence, and presence (≥10%) of the cribriform pattern is an independent predictor of recurrence, identifying a poor prognostic subset of acinar predominant tumors. Our findings highlight the important prognostic value of comprehensive histologic subtyping and recording the percentage of each histologic pattern, according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification with the addition of the cribriform subtype.

Keywords: lung adenocarcinoma, cribriform, histologic subtype, recurrence

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide.1, 2 In most countries, adenocarcinoma is the most common histologic type of lung cancer.3 Accumulating evidence suggests that the architectural pattern of lung adenocarcinoma can be used to stratify tumors with respect to prognosis.4–8 The newly proposed International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), American Thoracic Society (ATS), and European Respiratory Society (ERS) international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma emphasizes the prognostic significance of the predominant histologic subtype in lung adenocarcinoma,9 a finding that has been validated in independent cohorts.10–12 For stage I tumors, histologic subtyping can be used to stratify patients into three prognostic groups (low, intermediate, and high architectural grade).6, 10, 13

In the 2011 IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma, acinar pattern is defined as glandular structures that are round to oval shaped, with a central luminal space surrounded by tumor cells; cribriform arrangements are also regarded as a pattern of acinar adenocarcinoma.9 The word cribriform is derived from the Latin cribrum (for “sieve”) and is used to describe tumors characterized by evenly spaced “back-to-back” glands lacking intervening stroma. The cribriform pattern has been well-recognized in various tumors, including adenoid cystic adenocarcinoma of the salivary gland,14, 15 lung,16, 17 and breast.18, 19 In addition, the cribriform arrangement has been recognized as a pattern of conventional adenocarcinoma in various organs.20–27 To our knowledge, however, the prognostic significance of the cribriform pattern for lung adenocarcinoma has not been established.

In this study, we determined (1) whether presence of the cribriform pattern correlates with higher risk of recurrence; (2) whether the cribriform predominant subtype can be used to further stratify prognosis, in addition to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification; and (3) whether the cribriform pattern correlates with cliniopathologic factors in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. As we addressed these questions, we considered whether the cribriform pattern should be added as a new subtype of lung adenocarcinoma.

Materials and methods

Patients

This retrospective study was approved by the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Institutional Review Board (WA0269-08). We reviewed all patients with pathologically confirmed stage I solitary lung adenocarcinoma who underwent surgical resection at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center between 1995 and 2009. Tumor slides were available for histologic evaluation from 1038 patients. Clinical data were collected from the prospectively maintained Thoracic Surgery Service lung adenocarcinoma database. Disease stage was assigned on the basis of the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging Manual.28 Subsets of the cases in this study have been previously published in manuscripts focused on architectural grading,6 histologic classification,10 nuclear grading,29 and immune microenvironment in lung adenocarcinoma.30

Histologic evaluation

All available hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides were reviewed by two pathologists (K.K. and W.D.T.) who were blinded to the patients’ clinical outcomes, using an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with a standard 22-mm diameter eyepiece. Each tumor was reviewed using comprehensive histologic subtyping, and the percentage of each histologic component was recorded in 5% increments.9 The predominant pattern was defined as the morphologic subtype present in the greatest proportion. Tumors were classified, according to the original IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, as adenocarcinoma in situ; minimally invasive adenocarcinoma; and invasive adenocarcinoma, which was further subdivided into lepidic predominant, acinar predominant, papillary predominant, micropapillary predominant, and solid predominant. Variants included invasive mucinous and colloid predominant adenocarcinoma.9 Tumors were graded using an architectural approach, on the basis of predominant subtype, as (1) low grade (adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, or lepidic predominant), (2) intermediate grade (papillary or acinar predominant), and (3) high grade (micropapillary predominant, solid predominant, invasive mucinous, or colloid predominant).6, 10, 13

The cribriform pattern was defined by invasive back-to-back fused tumor glands with poorly formed glandular spaces lacking intervening stroma or invasive tumor nests of tumors cells that produce glandular lumina without solid components, which is similar to the definition of the cribriform pattern in Gleason score 4 for prostatic carcinoma and of invasive cribriform carcinoma of the breast.23, 24, 26 The percentage of cribriform component was also recorded in 5% increments. Tumors were re-classified based on predominant patterns, like the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, with the addition of the cribriform subtype.

Nuclear features were examined with a high-power field (HPF) of ×400 magnification (0.237-mm2 field of view). Nuclear atypia was identified in the area with the highest degree of atypia and was graded as follows: (1) mild: nuclei were uniform in size and shape; (2) moderate: nuclei were of intermediate size and had slight irregularity; and (3) severe: nuclei were enlarged to varying degrees, with some nuclei at least twice as large as others.4, 29, 31–33 Mitoses were evaluated at 50 HPFs in areas with the highest mitotic activity and were counted as the average number of mitotic figures per 10 HPFs.4, 34–36 According to the mitotic count, tumors were classified as follows: (1) low: 0–1 mitotic figures per 10 HPFs; (2) intermediate: 2–4 mitotic figures per 10 HPFs; or (3) high: ≥5 mitotic figures per 10 HPFs.29, 33

The following histologic factors were also investigated: (1) visceral pleural invasion, which was classified as absent (PL0) or present (PL1 and PL2)28; (2) lymphatic and vascular invasion; and (3) necrosis.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

In brief, 4 lm-thick sections from the microarray blocks which we constructed in our previous studies were deparaffinized.30, 36 Antigen retrieval was conducted using citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The standard avidin-biotinperoxidase complex was used for immunostaining of anti–TTF-1 antibody (SPT24 [Novocastra Laboratories], diluted at 1:50) and anti–ALK antibody (clone 5A4 [Adcam], diluted at 1:30). Sections were stained using a Ventana Discovery XT automated immunohistochemical stainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, Ariz), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. For TTF-1 immunostaining, normal lung tissues were stained as positive controls in parallel with the study tissues. For ALK immunostaining, lung adenocarcinoma tissues, in which ALK rearrangement were detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), were stained as positive controls in parallel with the study tissues.

The staining intensity of TTF-1 (nuclear staining) and ALK (cytoplasmic staining) was scored as 0 (no expression), 1 (mild), 2 (intermediate), or 3 (strong) in each tumor core as our recent publication,36 and the average intensity score for the tumor cores was considered to be the TTF-1 and ALK expression for each patient. TTF-1 expression was dichotomized into negative (score of 0) versus positive (score of >0) as we recently reported.36 ALK expression was dichotomized into negative (score of 0–1) versus positive (score of >1), according to the reported correlations between ALK protein expression determined by immunohistochemistry and ALK rearrangement determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization.37–39

Mutations analyses

EGFR (Epidermal growth factor receptor) exon 19 deletion and exon 21 L858R mutation was detected through a polymerase chain reaction-based assay, as previously described.40 KRAS exon 2 mutation was detected through direct sequencing.41

Statistical analysis

Associations between variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test (for categorical variables) and the Wilcoxon test (for continuous variables). We used recurrence-free probability—defined as the time from surgery to recurrence—as the primary endpoint. Patient recurrence data were censored at the date of death or of the last follow-up if no recurrence was recorded. Recurrence-free probability was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method, and nonparametric group comparisons were performed using the log-rank test. Multivariate analyses were performed using Cox proportional hazards regression. All P values were based on two-tailed statistical analysis, and P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (R Development Core Team; 2010) software, including the “survival” package.

Results

Association between patient clinicopathologic characteristics and recurrence

The clinicopathologic factors for all 1038 patients are listed in Table 1. The median age of patients was 69 years (range, 23–96 years). Most patients were women (62%), and most had stage IA disease (70%). With regard to surgical procedure, 77% underwent lobectomy, and 23% underwent sublobar resection (segmentectomy [n=76] and wedge resection [n=166]). Only fourteen (1%) patients received adjuvant chemotherapy. Visceral pleural invasion was observed in 17% of patients, lymphatic invasion in 32%, vascular invasion in 25%, and necrosis in 16%.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics and their association with recurrence

| Total | N | (%) | 5-yr recurrence- free probability |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 1038 | (100) | 82% | |

| Age | 0.88 | |||

| ≤65 | 378 | (36) | 81% | |

| >65 | 660 | (64) | 82% | |

| Gender | 0.002 | |||

| Female | 646 | (62) | 86% | |

| Male | 392 | (38) | 75% | |

| Smoking status | 0.17 | |||

| Never | 176 | (17) | 85% | |

| Former/current | 862 | (83) | 81% | |

| Laterality | 0.51 | |||

| Right | 611 | (59) | 83% | |

| Left | 427 | (41) | 80% | |

| Surgical procedure | <0.001 | |||

| Lobectomy | 796 | (77) | 85% | |

| Sublobar resection | 242 | (23) | 71% | |

| Stage | < 0.001 | |||

| IA | 731 | (70) | 86% | |

| IB | 307 | (30) | 72% | |

| Pleural invasion | <0.001 | |||

| Absence | 866 | (83) | 84% | |

| Presence | 172 | (17) | 70% | |

| Lymphatic invasion | <0.001 | |||

| Absence | 707 | (68) | 87% | |

| Presence | 331 | (32) | 71% | |

| Vascular invasion | <0.001 | |||

| Absence | 778 | (75) | 86% | |

| Presence | 260 | (25) | 70% | |

| Necrosis | <0.001 | |||

| Absence | 869 | (84) | 86% | |

| Presence | 169 | (16) | 64% | |

| Nuclear atypia | <0.001 | |||

| Mild | 451 | (43) | 86% | |

| Moderate | 360 | (35) | 83% | |

| Severe | 227 | (22) | 73% | |

| Mitosis | <0.001 | |||

| Low | 522 | (50) | 89% | |

| Intermediate | 216 | (21) | 80% | |

| High | 300 | (29) | 71% |

Significant p-values are shown in bold.

During the study period, 14% of patients (n=144) experienced a recurrence, and 15% (n=151) died from other causes without a recurrence. The median follow-up period for patients who did not experience a recurrence was 37.4 months (range, 0.3–160.0 months). In univariate analysis, male sex (P=0.002), sublobar resection (P<0.001), higher stage (P<0.001), pleural invasion (P<0.001), lymphatic invasion (P<0.001), vascular invasion (P<0.001), necrosis (P<0.001), greater nuclear atypia (P<0.001), and higher mitotic count (P<0.001) were associated with lower recurrence-free probability (Table 1).

Histologic features of the cribriform pattern

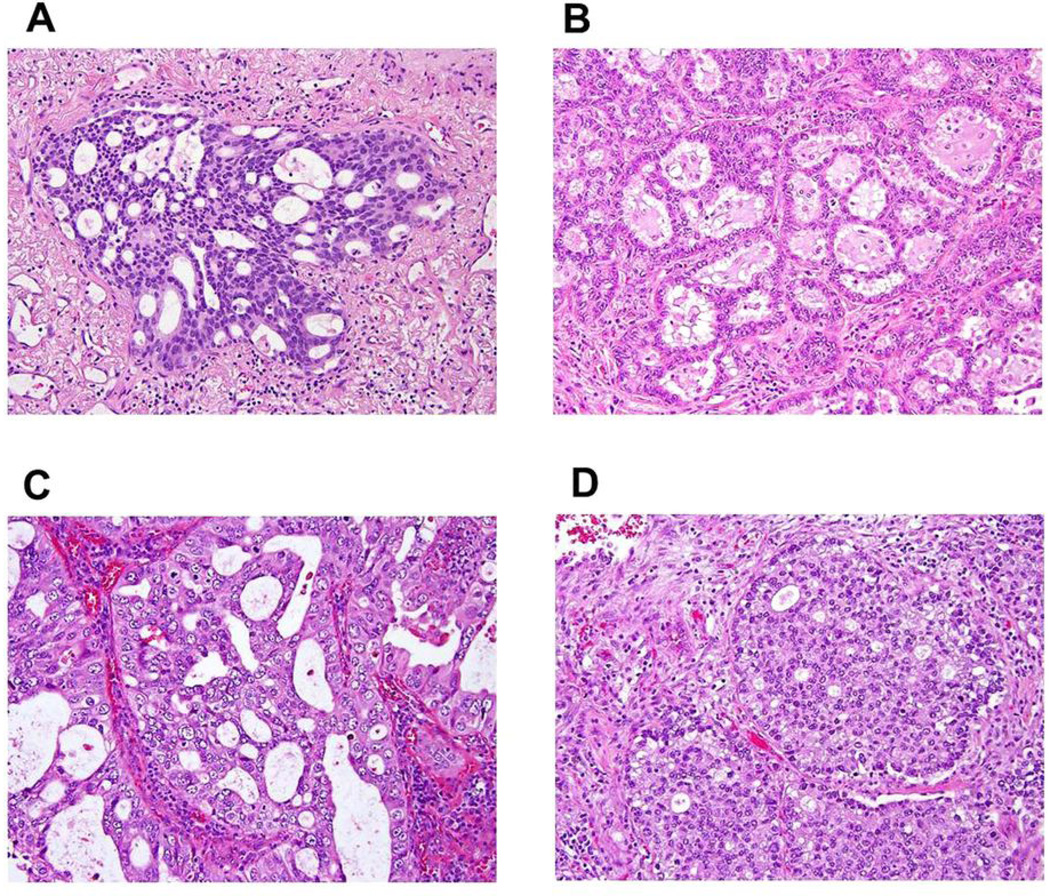

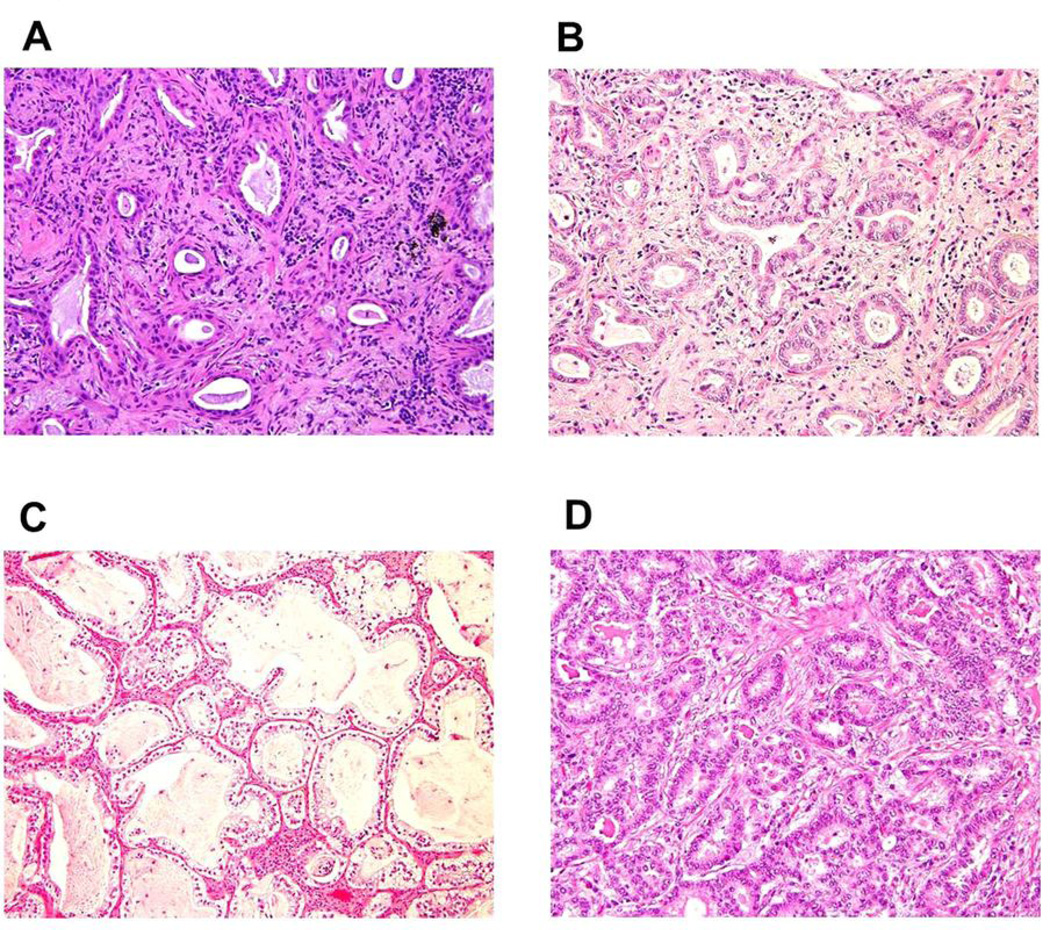

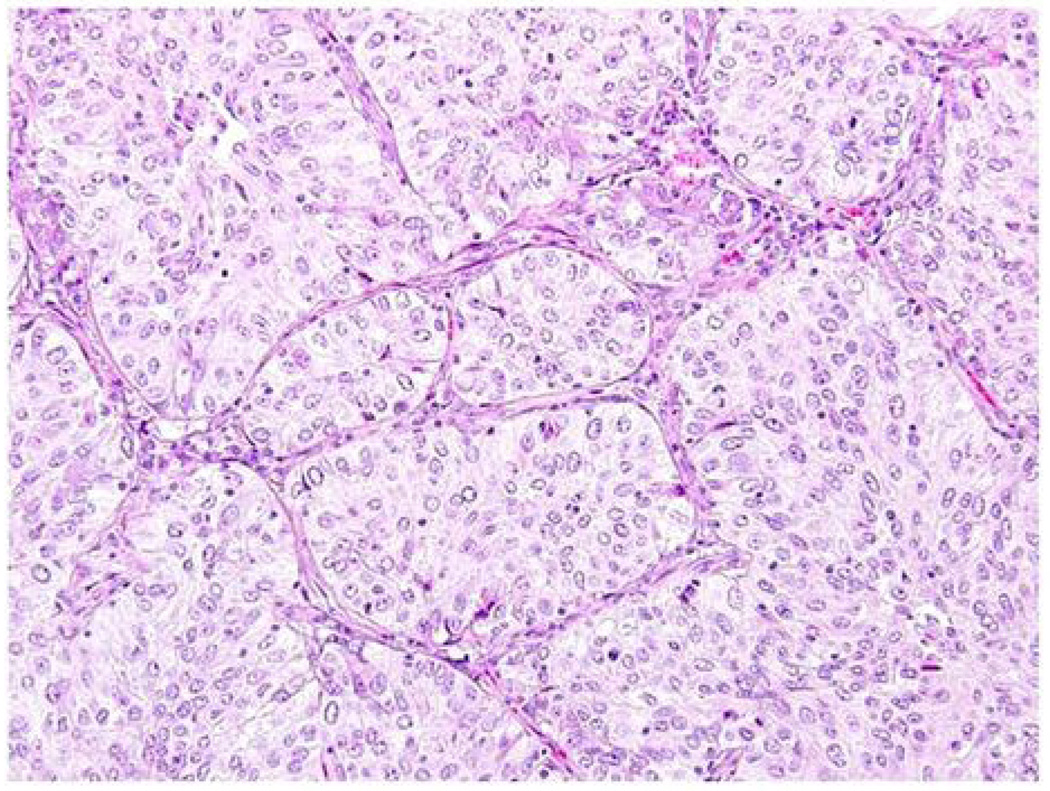

Cribriform pattern tumors had invasive fused tumor glands with back-to-back, poorly formed glandular spaces lacking intervening stroma or invasive tumor nests that produce small glandular lumina without solid components (Figure 1A–C). These tumors sometimes have a “cookie-cutter” pattern of gland-like spaces (Figure 1D). In contrast, the usual acinar pattern had well-defined individual tumor glands with well-formed glandular lumina (Figure 2A–D). Solid pattern tumors had invasive solid tumor nests without glandular space (Figure 3). The cribriform pattern was present in 25% of all tumors (n=262); among tumors with cribriform pattern, the average percentage of cribriform component was 21% (median, 18%; range, 5%–80%). Table 2 presents the numbers of cases of each predominant histologic subtype classified according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, as well as with the cribriform pattern as an additional subtype. With the cribriform pattern added as a subtype, tumors were identified in the following numbers: 46 (4%) cribriform predominant, 2 (0.2%) adenocarcinoma in situ, 34 (3%) minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, 106 (10%) lepidic predominant, 356 (34%) acinar predominant, 242 (23%) papillary predominant, 60 (6%) micropapillary predominant, 139 (13%) solid predominant, 44 (4%) invasive mucinous, and 9 (1%) colloid predominant. After the addition of the cribriform subtype, 46 (11%) of the acinar predominant tumors (according to the original IASLC/ATS/ERS classification; n=411) were reclassified as cribriform predominant, 3 (0.7%) were reclassified as lepidic predominant, 3 (0.7%) were reclassified as papillary predominant, and 3 (0.7%) were reclassified as solid predominant.

Figure 1. Cribriform pattern in lung adenocarcinoma.

(A) Invasive tumor nests with poorly-formed, small to intermediate-sized glandular spaces lacking intervening stroma. (B) Invasive fused tumor glands of intermediate-sized glandular spaces with extracellular mucin, lacking intervening stroma or having very thin stroma in limited areas between glandular spaces. (C) Invasive tumor nests with poorly-formed, intermediate-sized glandular spaces with back-to-back formations. (D) Invasive tumor nests with a few poorly-formed, small-sized glandular spaces with “cookie-cutter” patterns.

Figure 2. Acinar pattern in lung adenocarcinoma.

(A) Simple tumor glands of tumor cells with mild nuclear atypia and desmoplastic stroma. (B) Simple tumor glands of tumor cells with moderate nuclear atypia. (C) Large, simple tumor glands with clear cytoplasm and intraglandular mucin. (D) Crowded glands mixed with simple and some complex glandular spaces but having intervening stroma in most areas between glandular spaces.

Figure 3. Solid pattern in lung adenocarcinoma.

Solid pattern composed of invasive tumor nests without glandular spaces.

Table 2.

Distribution of histologic subtypes

| Histologic subtype | IASLC/ATS/ERS classification |

Our proposal introducing cribriform as a subtype |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | |

| Adenocarcinoma in situ | 2 | (0.2) | 2 | (0.2) |

| Minimally invasive adenocarcinoma | 34 | (3) | 34 | (3) |

| Invasive adenocarcinoma | ||||

| Lepidic predominant | 103 | (10) | 106 | (10) |

| Acinar predominant | 411 | (40) | 356 | (34) |

| Cribriform predominant | Not applicable | 46 | (4) | |

| Papillary predominant | 239 | (23) | 242 | (23) |

| Micropapillary predominant | 60 | (6) | 60 | (6) |

| Solid predominant | 136 | (13) | 139 | (13) |

| Variants | ||||

| Invasive mucinous | 44 | (4) | 44 | (4) |

| Colloid predominant | 9 | (1) | 9 | (1) |

Association between histologic subtype, including cribriform pattern, and recurrence

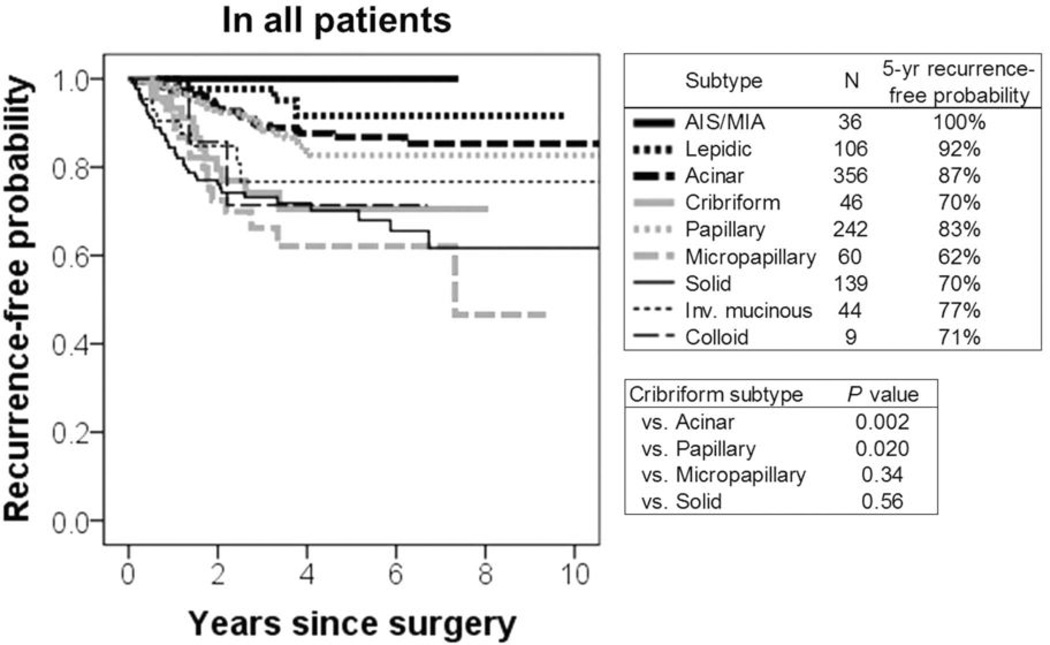

The 5-year recurrence-free probability for patients with cribriform predominant tumors (n=46) was 70%. Patients with adenocarcinoma in situ or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (n=36) experienced no recurrences (5-year recurrence-free probability, 100%). Patients with lepidic predominant tumors (n=106) had a low risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 92%). Patients with acinar (n=356) and papillary (n=242) predominant tumors had an intermediate risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 87% and 83%, respectively). Patients with micropapillary predominant (n=60), solid predominant (n=139), invasive mucinous (n=44), and colloid predominant (n=9) tumors had a high risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 62%, 70%, 77%, and 71%, respectively). The recurrence-free probability for patients with cribriform predominant tumors was significantly lower than that for patients with acinar or papillary predominant tumors (P=0.002 and P=0.020, respectively) but was comparable to that for patients with micropapillary or solid predominant tumors (P=0.34 and P=0.56, respectively) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Recurrence-free probability by use of the cribriform pattern as a subtype, in addition to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification.

The 5-year recurrence-free probability for patients with cribriform predominant tumors (n=46) was 70%. Patients with adenocarcinoma in situ or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma tumors (n=36) experienced no recurrences (5-year recurrence-free probability, 100%). Patients with lepidic predominant tumors (n=106) had a low risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 92%). Patients with acinar (n=356) and papillary (n=242) predominant tumors had an intermediate risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 87% and 83%, respectively). Patients with micropapillary predominant (n=60), solid predominant (n=139), invasive mucinous (n=44), and colloid predominant (n=9) tumors had a high risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 62%, 70%, 77%, and 71%, respectively).

When we considered cribriform pattern as solid pattern in histologic analysis, patients with solid predominant tumors (including cribriform pattern as solid pattern; n=205) remained at high risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 70%). Among this group of patients, those with tumors newly classified as solid predominant (n=69) as a result of the inclusion of the cribriform pattern in this subtype also had a high risk of recurrence (5-year recurrence-free probability, 71%).

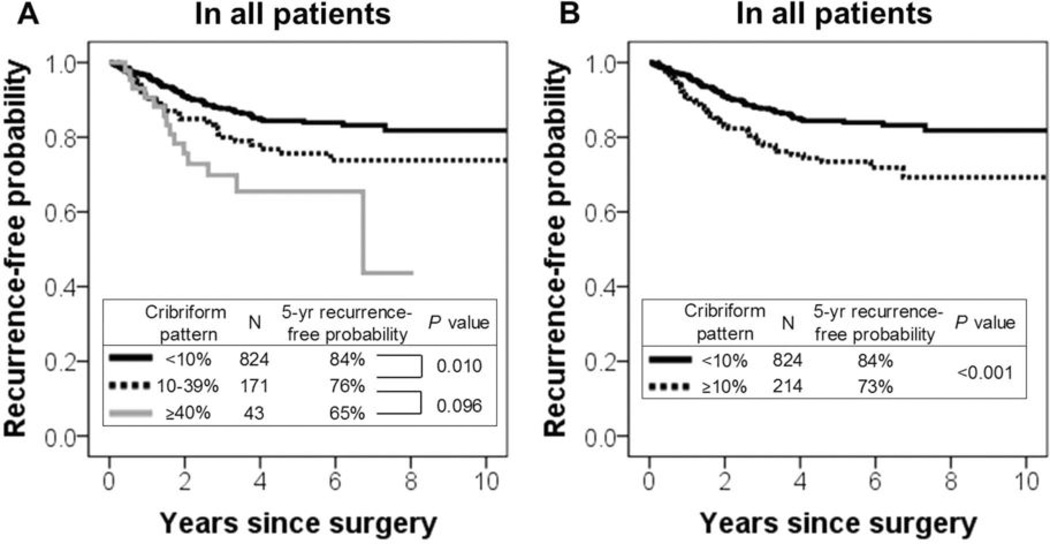

When we stratified tumors by percentage of cribriform pattern, the 5-year recurrence-free probability was 84% for 0% cribriform pattern (n=776), 87% for 5% cribriform pattern (n=48), 74% for 10% cribriform pattern (n=83), 76% for 20% cribriform pattern (n=54), 80% for 30% cribriform pattern (n=34), 67% for 40% cribriform pattern (n=16), and 64% for ≥50% cribriform pattern (n=27). We then regrouped the tumors into three groups on the basis of cribriform percentage (<10%, 10%–39%, and ≥40%). The recurrence-free probability for patients with 10%–39% cribriform pattern (n=171) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 76%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern (n=824; 5-year recurrence-free probability, 84%; P=0.010). The recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥40% cribriform pattern (n=43) was lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 65%) than that for patients with 10%–39% cribriform pattern, although the difference was not significant (P=0.096) (Figure 5A). Finally, we classified tumors into two groups on the basis of cribriform percentage (<10% and ≥10%). The recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥10% cribriform pattern tumors (n=214) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 73%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern tumors (n=824; 5-year recurrence-free probability, 84%; P<0.001) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Recurrence- free probability, by cribriform pattern percentage, in all patients.

(A) The recurrence-free probability for patients with 10%–39% cribriform pattern (n=171) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 76%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern (n=824; 5-year recurrence-free probability, 84%; P=0.010). The recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥40% cribriform pattern (n=43) was lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 65%) than that for patients with 10%–39% cribriform pattern, although the difference was not significant (P=0.096). (B) The recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥10% cribriform pattern (n=214) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 73%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern (n=824; 5-year recurrence-free probability, 84%; P<0.001).

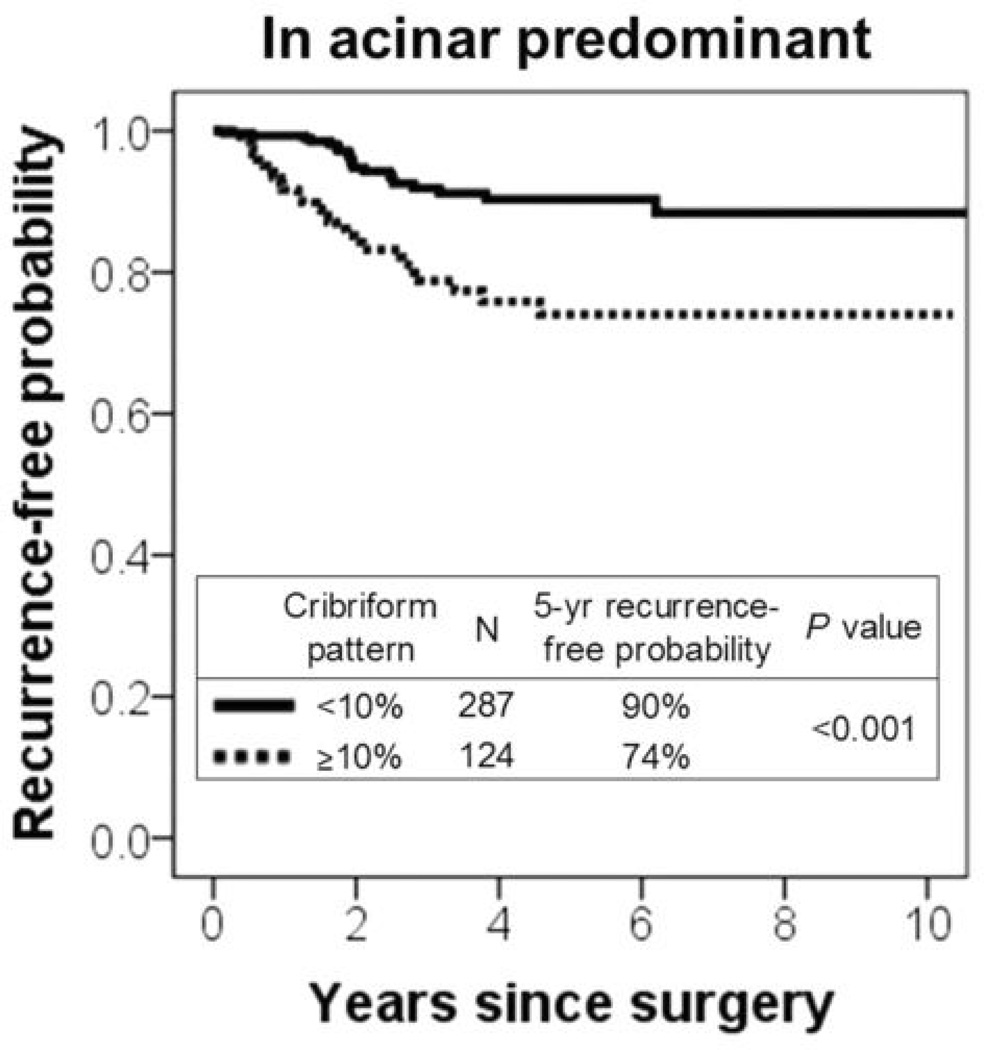

Among patients with acinar predominant tumors (according to the original IASLC/ATS/ERS classification), the recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥10% cribriform pattern tumors (n=124) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 74%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern tumors (n=287; 5-year recurrence-free probability, 90%; P<0.001) (Figure 6). The cribriform pattern (≥10%) was not identified in minimally invasive adenocarcinoma or invasive mucinous tumors. Only small numbers of tumors had a cribriform component among lepidic (1% [1/103]), micropapillary (8% [5/60]), and colloid (11% [1/9]) predominant tumors. The cribriform pattern was identified in papillary (14% [34/239]) and solid (36% [49/136]) predominant tumors. However, presence (≥10%) of the cribriform pattern did not correlate with the risk of recurrence among patients with papillary (P=0.67) or solid (P=0.94) predominant tumors.

Figure 6. Recurrence-free probability, by cribriform pattern percentage, among patients with acinar predominant tumors.

Among patients with acinar predominant tumors according to the original IASLC/ATS/ERS classification, the recurrence-free probability for patients with ≥10% cribriform pattern (n=124) was significantly lower (5-year recurrence-free probability, 74%) than that for patients with <10% cribriform pattern (n=287; 5-year recurrence-free probability, 90%; P<0.001).

When multivariate analysis was performed with tumors reclassified to include the cribriform predominant subtype (Table 3), patients with cribriform predominant tumors remained at significantly increased risk of recurrence, compared with patients with low architectural grade tumors (adenocarcinoma in situ, minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and lepidic predominant; P=0.033); however, presence of the cribriform pattern was not independently associated with the risk of recurrence, compared with intermediate architectural grade (acinar and papillary predominant; P=0.13). In addition, male sex (P=0.012), sublobar resection (P<0.001), higher stage (IB; P<0.001), lymphatic invasion (P=0.027), and necrosis (P=0.001) were independently associated with the risk of recurrence. When multivariate analysis was performed with tumors classified according to the original IASLC/ATS/ERS classification with acinar predominant tumors stratified by percentage of cribriform pattern (≥10% vs. <10%) (Table 4), patients with acinar predominant tumors with ≥10% cribriform pattern remained at significantly increased risk of recurrence, compared with those with <10% cribriform pattern (P=0.042).

Table 3.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cribriform predominant | |||

| vs. Low grade | 3.64 | 1.11–11.90 | 0.033 |

| vs. Intermediate grade | 1.65 | 0.86–3.16 | 0.13 |

| vs. High grade | 0.77 | 0.41–1.44 | 0.41 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.53 | 1.10–2.14 | 0.012 |

| Surgery (sublobar vs. lobar) | 3.23 | 2.24–4.66 | <0.001 |

| Stage (IB vs. IA) | 2.02 | 1.41–2.88 | <0.001 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 1.51 | 1.05–2.16 | 0.027 |

| Necrosis | 1.96 | 1.32–2.92 | 0.001 |

| Mitotic count | |||

| Intermediate vs. low | 1.34 | 0.82–2.18 | 0.24 |

| High vs. low | 1.53 | 0.97–2.41 | 0.065 |

Significant p-values are shown in bold.

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Table 4.

Multivariate Cox proportional hazards model

| Variable | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histologic subtype (vs. acinar predominant with <10% cribriform) |

|||

| Low grade | 0.58 | 0.20–1.72 | 0.33 |

| Papillary | 1.40 | 0.79–2.49 | 0.25 |

| Acinar predominant with ≥10% cribriform | 1.88 | 1.02–3.45 | 0.042 |

| High grade | 2.88 | 1.70–4.89 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.53 | 1.10–2.14 | 0.012 |

| Surgery (sublobar vs. lobar) | 3.23 | 2.24–4.66 | <0.001 |

| Stage (IB vs. IA) | 1.97 | 1.38–2.80 | <0.001 |

| Lymphatic invasion | 1.50 | 1.04–2.15 | 0.030 |

| Necrosis | 1.95 | 1.31–2.90 | 0.001 |

| Mitotic count | |||

| Intermediate vs. low | 1.27 | 0.77–2.07 | 0.35 |

| High vs. low | 1.46 | 0.93–2.31 | 0.10 |

Significant p-values are shown in bold.

HR, Hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval

Associations between cribriform pattern and clinicopathologic factors

Presence (≥10%) of cribriform pattern was associated with smoking history (P=0.024), higher stage (IB; P<0.001), pleural invasion (P<0.001), lymphatic invasion (P<0.001), vascular invasion (P<0.001), necrosis (P<0.001), greater nuclear atypia (P<0.001), and higher mitotic count (P<0.001).

Associations between cribriform pattern and molecular expressions (TTF-1 and ALK) or gene mutations (EGFR and KRAS)

TTF-1 negativity was more frequently observed in cribriform predominant tumors (17%) than non-cribriform predominant tumors (7%) although the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.057). Cribriform predominant tumors did not correlate with ALK expression, EGFR mutation, or KRAS mutation (data not shown).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that, in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma, (1) cribriform predominant tumors have a high risk of recurrence, similar to that for solid predominant tumors; (2) the cribriform pattern (≥10%) can be used to stratify acinar predominant tumors with respect to recurrence; (3) acinar predominant subtype with the cribriform pattern (≥10%) is an independent factor of poor prognosis that predicts recurrence; and (4) the cribriform pattern correlates with several clinicopathologic factors, including smoking history, higher stage, tumor invasiveness, greater nuclear atypia, and higher mitotic count. Our findings highilight the important prognostic value of comprehensive histologic subtyping and recording the percentage of each histologic pattern, according to the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification with the addition of the cribriform subtype. We next consider the implications of this finding for further refinement of lung adenocarcinoma subclassification.

In lung adenocarcinoma, the cribriform pattern has been reported to correlate with ALK rearrangement from Japanese cohorts.20, 21 In contrast, studies from the USA did not identify an association between the cribriform pattern and ALK rearrangement.42 In our study, there was no correlation identified between cribriform predominant tumors and ALK expression. One limitation of this finding is that ALK rearrangement has not been confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization. However, very high correlation between ALK immunohistochemistry and the ALK rearrangement has been demonstrated in recent studies.37, 38, 43 Especially, anti-ALK monoclonal antibody 5A4, which was used in our study, offered 95–100% sensitivity and specificity to identify tumors with ALK rearrangement determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization in NSCLC.37, 38, 43 In our series, regarding other molecular correlations, cribriform pattern was not associated with EGFR or KRAS mutations. TTF-1 negativity was more frequently observed in cribriform predominant tumors (17%) than non-cribriform predominant tumors (7%). This proportion of TTF-1 negativity in cribriform predominant tumors was similar to that of solid predominant tumors (14%) in our previous study, and was higher than that of acinar predominant tumors (6%).36 This finding may support that cribriform predominant tumors would be similar to solid predominant tumors rather than acinar predominant tumors for its poor prognosis as well as for its higher tendency of TTF-1 negativity.

There has also been some debate whether the cribriform pattern should be included in the acinar or the solid subtype. The prognostic utility of the cribriform pattern has not been defined for lung adenocarcinoma, although several previous studies have reported correlations between cribriform pattern and prognosis in adenocarcinoma of various organs.22–27 In prostatic adenocarcinoma, the cribriform pattern has been recognized as a higher grade pattern (Gleason score 4) than the acinar pattern, which comprises simple glandular structures (Gleason score 3).22–24 Egashira et al. reported that the presence of a cribriform structure was a significant risk factor for lymph node metastasis in invasive colon cancer.25 In breast cancer, contrarily, the cribriform pattern has been correlated with better survival, compared with invasive ductal cancer (not otherwise specified).26, 27 In our study, presence of the cribriform pattern correlated with higher risk of recurrence and was able to further stratify the prognosis for acinar predominant tumors. Furthermore, the prognosis for cribriform predominant tumors (5-year recurrence-free probability, 70%) was comparable to that for solid predominant tumors (5-year recurrence-free probability, 70%) and was significantly worse than that for acinar (5-year recurrence-free probability, 87%) and papillary (5-year recurrence-free probability, 83%) predominant tumors. One limitation of the IASLC/ATS/ERS classification is that the highest percentage of patients (approximately 40%) is classified as having acinar predominant tumors.10, 11 Thus, it would be helpful to recognize poor prognostic factors among acinar subtype tumors. In addition, our study has demonstrated that presence of the cribriform pattern can be used to stratify acinar predominant tumors, with respect to recurrence, into two groups (5-year recurrence-free probability, 74% for ≥10% cribriform pattern vs. 90% for <10% cribriform pattern). In multivariate analysis, the prognostic value of the cribriform pattern remained significant even after adjustment for clinicopathologic factors, including pathologic tumor-node-metastasis stage. With these results taken into account, the cribriform pattern should be recognized and reported in usual pathologic practice, and it should be considered a new histologic subtype of lung adenocarcinoma.

In addition to its correlation with prognosis, the cribriform pattern was associated with smoking history and higher stage. Furthermore, presence of the cribriform pattern was associated with aggressive hisologic findings: tumor invasiveness (pleural, lymphatic, and vascular invasion), greater nuclear atypia, and proliferation (mitosis). These observations demonstrate that the cribriform pattern reflects aggressive tumor biology in adenocarcinoma.

In conclusion, presence of the cribriform pattern (currently a subcategory of the acinar pattern) is an independent factor of poor prognosis, with respect to recurrence, in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. In our series, the cribriform predominant subtype occurred with the same frequency as the invasive mucinous subtype, was more common than the adenocarcinoma in situ or minimally invasive adenocarcinoma subtype, and was almost as common as the micropapillary predominant subtype. Histologic evaluation that includes consideration of the cribriform pattern may result in better prognostic stratification, compared with that achieved by use of the current IASLC/ATS/ERS classification alone, as it identifies a subset of acinar predominant tumors with poor prognosis in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Therefore, we propose that the cribriform pattern should be recorded in pathologic analysis and that it should be considered a new histologic subtype of lung adenocarcinoma, in addition to the subtypes in the current IASLC/ATS/ERS classification. Since morphologic assessment using hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides is routine clinical practice for resected lung adenocarcinoma, prognostic stratification that includes the cribriform pattern should be prospectively tested in future clinical trials, to improve the ability to identify patients with early-stage lung adenocarcinoma with an unfavorable prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joe Dycoco for his help with the lung adenocarcinoma database in the Division of Thoracic Service, Department of Surgery; and David Sewell, for his editorial assistance.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported, in part, by William H. Goodwin and Alice Goodwin, the Commonwealth Foundation for Cancer Research and the Experimental Therapeutics Center; the National Cancer Institute (grants R21CA164568, R21CA164585, U54CA137788 and U54CA132378); and the U.S. Department of Defense (grant LC110202 and PR101053).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosures

All authors affirm no actual or potential conflicts of interest, including any financial, personal, or other relationships with other people or organizations.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2011. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Devesa SS, Bray F, Vizcaino AP, Parkin DM. International lung cancer trends by histologic type: male:female differences diminishing and adenocarcinoma rates rising. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:294–299. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barletta JA, Yeap BY, Chirieac LR. Prognostic significance of grading in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2010;116:659–669. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motoi N, Szoke J, Riely GJ, et al. Lung adenocarcinoma: modification of the 2004 WHO mixed subtype to include the major histologic subtype suggests correlations between papillary and micropapillary adenocarcinoma subtypes, EGFR mutations and gene expression analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:810–827. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31815cb162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sica G, Yoshizawa A, Sima CS, et al. A grading system of lung adenocarcinomas based on histologic pattern is predictive of disease recurrence in stage I tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1155–1162. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181e4ee32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeshima AM, Tochigi N, Yoshida A, et al. Histological scoring for small lung adenocarcinomas 2 cm or less in diameter: a reliable prognostic indicator. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:333–339. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181c8cb95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi M, Morikawa A, Kawasaki M, et al. Small adenocarcinoma of the lung. Histologic characteristics and prognosis. Cancer. 1995;75:2844–2852. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950615)75:12<2844::aid-cncr2820751209>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshizawa A, Motoi N, Riely GJ, et al. Impact of proposed IASLC/ATS/ERS classification of lung adenocarcinoma: prognostic subgroups and implications for further revision of staging based on analysis of 514 stage I cases. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:653–664. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell PA, Wainer Z, Wright GM, et al. Does lung adenocarcinoma subtype predict patient survival?: A clinicopathologic study based on the new International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary lung adenocarcinoma classification. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1496–1504. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318221f701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshizawa A, Sumiyoshi S, Sonobe M, et al. Validation of the IASLC/ATS/ERS lung adenocarcinoma classification for prognosis and association with EGFR and KRAS gene mutations: analysis of 440 Japanese patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:52–61. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182769aa8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadota K, Colovos C, Suzuki K, et al. FDG-PET SUVmax combined with IASLC/ATS/ERS histologic classification improves the prognostic stratification of patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3598–3605. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2414-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freier K, Flechtenmacher C, Walch A, et al. Differential KIT expression in histological subtypes of adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland. Oral Oncology. 2005;41:934–939. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaso J, Malhotra R. Adenoid cystic carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:511–515. doi: 10.5858/2009-0527-RS.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aubry M-C, Heinrich MC, Molina J, et al. Primary adenoid cystic carcinoma of the lung. Cancer. 2007;110:2507–2510. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molina JR, Aubry MC, Lewis JE, et al. Primary salivary gland-type lung cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:2253–2259. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azoulay S, Lae M, Freneaux P, et al. KIT is highly expressed in adenoid cystic carcinoma of the breast, a basal-like carcinoma associated with a favorable outcome. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:1623–1631. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabban JT, Swain RS, Zaloudek CJ, Chase DR, Chen YY. Immunophenotypic overlap between adenoid cystic carcinoma and collagenous spherulosis of the breast: potential diagnostic pitfalls using myoepithelial markers. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1351–1357. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jokoji R, Yamasaki T, Minami S, et al. Combination of morphological feature analysis and immunohistochemistry is useful for screening of EML4-ALK-positive lung adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2010;63:1066–1070. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.081166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida A, Tsuta K, Nakamura H, et al. Comprehensive histologic analysis of ALK-rearranged lung carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1226–1234. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182233e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin MA, de La Taille A, Bagiella E, Olsson CA, O'Toole KM. Cribriform carcinoma of the prostate and cribriform prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia: incidence and clinical implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:840–848. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein JI. An Update of the Gleason Grading System. J Urol. 2010;183:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iczkowski KA, Torkko KC, Kotnis GR, et al. Digital quantification of five high-grade prostate cancer patterns, including the cribriform pattern, and their association with adverse outcome. Am J Clin Pathol. 2011;136:98–107. doi: 10.1309/AJCPZ7WBU9YXSJPE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egashira Y, Yoshida T, Hirata I, et al. Analysis of pathological risk factors for lymph node metastasis of submucosal invasive colon cancer. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:503–511. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis IO, Galea M, Broughton N, et al. Pathological prognostic factors in breast cancer. II. Histological type. Relationship with survival in a large study with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 1992;20:479–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1992.tb01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colleoni M, Rotmensz N, Maisonneuve P, et al. Outcome of special types of luminal breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1428–1436. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2009. pp. 253–270. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kadota K, Suzuki K, Kachala SS, et al. A grading system combining architectural features and mitotic count predicts recurrence in stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1117–1127. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suzuki K, Kadota K, Sima CS, et al. Clinical impact of immune microenvironment in stage I lung adenocarcinoma: tumor interleukin-12 receptor beta2 (IL-12Rbeta2), IL-7R, and stromal FoxP3/CD3 ratio are independent predictors of recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:490–498. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas JS, Kerr GR, Jack WJ, et al. Histological grading of invasive breast carcinoma - a simplification of existing methods in a large conservation series with long-term follow-up. Histopathology. 2009;55:724–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asamura H, Ando M, Matsuno Y, Shimosato Y. Histopathologic prognostic factors in resected adenocarcinomas: is nuclear DNA content prognostic? Chest. 1999;115:1018–1024. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.4.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kadota K, Suzuki K, Colovos C, et al. A nuclear grading system is a strong predictor of survival in epitheloid diffuse malignant pleural mesothelioma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:260–271. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Travis WD, Rush W, Flieder DB, et al. Survival analysis of 200 pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors with clarification of criteria for atypical carcinoid and its separation from typical carcinoid. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:934–944. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199808000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baak JP. Mitosis counting in tumors. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:683–685. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(90)90026-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kadota K, Nitadori J, Sarkaria IS, et al. Thyroid transcription factor-1 expression is an independent predictor of recurrence and correlates with the IASLC/ATS/ERS histologic classification in patients with stage I lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2013;119:931–938. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paik JH, Choi C-M, Kim H, et al. Clinicopathologic implication of ALK rearrangement in surgically resected lung cancer: A proposal of diagnostic algorithm for ALK-rearranged adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2012;76:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paik JH, Choe G, Kim H, et al. Screening of anaplastic lymphoma kinase rearrangement by immunohistochemistry in non-small cell lung cancer: correlation with fluorescence In situ hybridization. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:466–472. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31820b82e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi ES, Boland JM, Maleszewski JJ, et al. Correlation of IHC and FISH for ALK gene rearrangement in non-small cell lung carcinoma: IHC score algorithm for FISH. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:459–465. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318209edb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan Q, Pao W, Ladanyi M. Rapid polymerase chain reaction-based detection of epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations in lung adenocarcinomas. J Mol Diagn. 2005;7:396–403. doi: 10.1016/S1525-1578(10)60569-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pao W, Wang TY, Riely GJ, et al. KRAS mutations and primary resistance of lung adenocarcinomas to gefitinib or erlotinib. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishino M, Klepeis VE, Yeap BY, et al. Histologic and cytomorphologic features of ALK-rearranged lung adenocarcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1462–1472. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLeer-Florin A, Moro-Sibilot D, Melis A, et al. Dual IHC and FISH Testing for ALK Gene Rearrangement in Lung Adenocarcinomas in a Routine Practice: A French Study. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:348–354. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182381535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]