Abstract

Objective

To compare grating (resolution) visual acuity at 6 years of age in eyes that received early treatment (ET) for high-risk prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) versus eyes that were managed conventionally (CM).

Methods

In a randomized clinical trial, infants with bilateral, high-risk prethreshold ROP (N=317) had one eye treated early at high-risk prethreshold disease and the other eye managed conventionally, and treated if ROP progressed to threshold severity. For asymmetric cases (N=84), the high-risk prethreshold eye was randomized to either ET or CM.

Main Outcome Measures

Grating visual acuity measured at 6 years of age by masked testers using Teller acuity cards.

Results

Monocular grating acuity results were obtained from 317 (86%) of 370 surviving children. Analysis of grating acuity results for all subjects with high-risk prethreshold ROP showed no statistically significant overall benefit for early treatment (18.1% vs 22.8% unfavorable outcome, P=0.08). When the 6-year grating acuity results were analyzed according to a clinical algorithm (high-risk Type 1 and high-risk Type 2 prethreshold ROP), a benefit was seen in Type 1 eyes (16.4% vs 25.2%, P=0.004) that were treated early, but not in Type 2 eyes (21.3% vs 15.9%, P=0.29).

Conclusion

Early treatment for eyes with Type 1 ROP improved grating acuity outcomes but early treatment for eyes with Type 2 ROP did not.

Application to Clinical Medicine

Type I eyes should be treated early; however, based on acuity results at age 6 years, Type 2 eyes should be cautiously monitored for progression to Type 1 ROP.

Trial Registration

The Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity (ETROP) Study determined that eyes with high-risk prethreshold ROP1 would benefit from early peripheral retinal ablation, compared to eyes managed conventionally. Results of the study, based on assessment of recognition (letter) acuity with Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) charts2 when children reached 6 years of age, indicated a benefit of early treatment in the subset of eyes that had high-risk Type 1 ROP at the time of randomization, but not in eyes with high-risk Type 2 ROP (Table 1).3

Table 1.

Definitions.

| Plus disease | Abnormal vascular dilation and tortuosity at least equal to that of a standard photograph (2 or more quadrants must be involved) | |

| Low-risk prethreshold ROP | Prethreshold with <15% Risk of unfavorable structural outcome based on RM-ROP2 criteria | |

| High-risk prethreshold ROP | Prethreshold with ≥ 15% Risk of unfavorable structural outcome based on RM-ROP2 criteria | |

| Zone I | Zone II | |

| Prethreshold ROP | ROP any stage | Stage 2 with plus disease |

| Stage 3 without plus disease | ||

| Stage 3 with plus, but less than threshold ROP | ||

| Threshold ROP | Stage 3 in 5 contiguous or 8 total sectors with plus disease | Stage 3 in 5 contiguous or 8 total sectors with plus disease |

| Type 1 ROP | any Stage ROP with plus | Stage 2 with plus disease |

| Stage 3 without plus | Stage 3 with plus | |

| Type 2 ROP | Stage 1 or 2 without plus | Stage 3 without plus |

Although the primary ETROP outcome analysis was based on ETDRS recognition acuity at 6 years, which is the “gold standard” for visual acuity assessment, not all ETROP Study participants had neurodevelopmental skills sufficient to perform a letter acuity task. The 6-year study examination also included assessment of grating (resolution) acuity using the Teller acuity card procedure.4, 5 The purpose of the present paper is to describe the results of assessment of grating acuity at age 6 years in ETROP Study participants. Results from early-treated (ET) versus conventionally-managed (CM) eyes are compared for all study eyes (i.e., all eyes that had high-risk prethreshold ROP), for eyes with Type 1 ROP and for eyes with Type 2 ROP.

Methods

Study Participants

Between October 1, 2000 and September 30, 2002, 401 infants developed high-risk prethreshold ROP and entered the randomized trial. Entry into the study was based on the presence of prethreshold ROP and a risk of blindness greater than or equal to 15% (high risk) as determined by a risk model (RM-ROP2) that was developed from an analysis of data from the CRYO-ROP Study1. High-risk prethreshold ROP was present in both eyes of 317 infants; these infants had one eye randomized to ET (at high-risk prethreshold ROP) and the other eye managed conventionally, with treatment if ROP reached threshold severity. If high-risk prethreshold ROP developed in only one eye and the fellow eye had less than severe or no ROP the high-risk eye was randomized to ET or to CM. This occurred in 84 infants. Details of the design of the ETROP Study6 and details of the model used to calculate whether an infant had high-risk ROP1 have been published.

Study protocols were approved by the review boards of all participating institutions, and parents provided written informed consent for participation in the extended follow-up study to allow vision measurements through 6 years of age.

Assessment of Grating Acuity

A tester who was masked to the treatment history and ocular status of each eye assessed each child’s monocular grating acuity with the Teller acuity card procedure,4, 5, 7–9 using the Teller Acuity Cards II (Stereo Optical, Co., Inc, Chicago, IL). The luminance of the cards was ≥ 10 cd/m2. Test distance was 84 cm, but could be reduced to 55 cm, 38 cm, 19 cm, or 9.5 cm for a child with low vision. Testing was usually conducted with a Teller acuity card stage (Vistech Consultants, Inc., Dayton, Ohio), which provided a uniform field in which to present the cards. However, the stage was not used with children who had poor vision, when a close test distance was needed, and with children who had nystagmus, for whom the tester used vertical presentation of the cards to allow easier detection of the grating lines.8 The right eye was tested first, followed by testing of the left eye. All eyes were tested with corrective lenses prescribed to meet study protocol criteria3. Assessment of grating acuity was performed prior to cycloplegia.

The tester, who was masked to the location of the grating on each card, presented the acuity cards sequentially, starting with a card containing a coarse (2.4 cycles/cm) grating. The tester used the child’s eye and head movements and/or the child’s pointing behavior in response to repeated presentations of each card to decide whether the child could discriminate the location of the grating on the card. If the child did not give evidence of seeing the initial (2.4 cycles/cm) grating, the tester continued testing with a card containing a coarser grating. The tester proceeded to cards containing finer and finer gratings until the child no longer gave evidence of being able to resolve the grating.4, 5 Based on the child’s responses, the tester determined the highest spatial frequency (finest grating) that the child could resolve, which was recorded as the grating acuity score for that eye.

Children who could not resolve the coarsest standard acuity card grating (0.32 cycle/cm) were tested with the Low Vision (LV) card, which has 2.2-cm-wide black-and-white stripes filling one side of the card. The tester was permitted to present the LV card at any distance, orientation, or location in the child’s visual field, to determine whether the child had pattern vision in that eye.

Children were exempted from the visual acuity examination but not from data analysis if both an ETROP Study-certified examiner and a parent agreed that both eyes had only light perception (LP) or worse vision, and the child had bilateral retinal detachments, phthisis bulbi, or bilateral enucleations.

Data Analysis

Data were included only if treatment for any amblyopia (judged by the examining ophthalmologist) had been prescribed for at least 4 weeks prior to the acuity test, and if refractive error(measured by cycloplegic retinoscopy) had been measured and corrected within three months of the acuity test. Correction was required for myopia ≥ 1.00 diopter (D); hyperopia ≥ 4.00 D; or astigmatism ≥ 1.50 D; and for anisometropia ≥ 1.50 D spherical equivalent or cylinder.

Grating acuity results were categorized and presented as normal (13 cycles/degree or better), below normal (worse than 13 cycles/degree and better than or equal to 6.4 cycles/degree or better), poor (measurable acuity worse than 6.4 cycles/degree), or blind/low vision (only the ability to detect the 2.2-cm-wide stripes on the LV Teller acuity card at any distance and at any location in the visual field, LP only, or no light perception (NLP)). Furthermore, acuity results in the normal and below normal categories were classified as “favorable” outcomes, and acuity results in the poor and blind/low vision categories were classified as “unfavorable” outcomes.

For statistical analysis, an adaptation of the Mantel-Haenszel chi-square procedure for matched pairs was used.10 This method allows data from children with bilateral disease to be combined with data from children with asymmetric disease. When analyzing only symmetrical disease, the paired eyes were analyzed using McNamara’s test for matched pairs.

Results

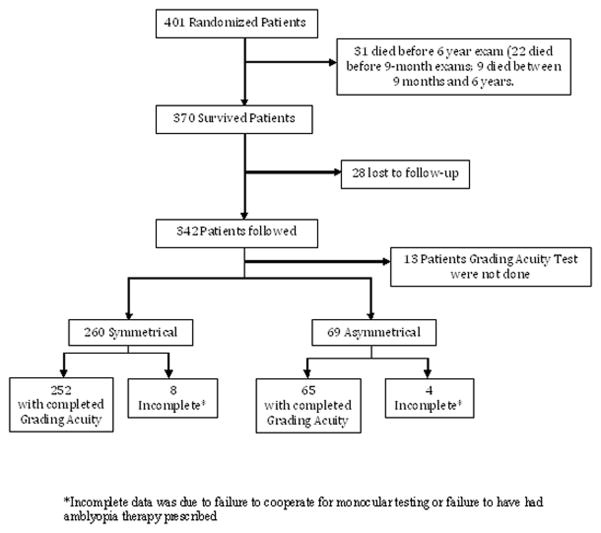

Of the 401 randomized infants, 370 survived until age 6 years (Figure 1), and 329 (88.9%) either had grating acuity assessed (n=317) or were exempted from acuity assessment due to bilateral blindness (n=12). Total of 329 children were included in the data analysis. Of these, 260 children had symmetric (bilateral) disease, and 69 children had asymmetric disease. Grating acuity data were incomplete for 8 children with symmetric disease, and 4 children with asymmetric disease.

Figure 1.

Algorithm (flow chart) for randomized infants.

*Incomplete data was due to failure to cooperate for monocular testing or failure to have had amblyopia therapy prescribed

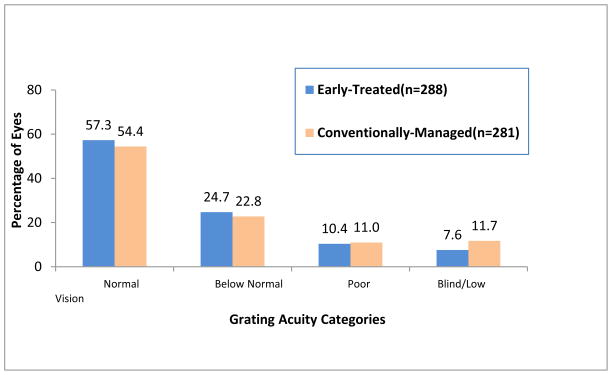

The proportion of randomized eyes with unfavorable grating acuity at age 6 years is shown in Table 2. Overall, 18.1% of ET high-risk prethreshold eyes and 22.8% of CM eyes had unfavorable outcomes, a difference that did not reach statistical significance (P=0.08). Within-subject comparisons in the children with bilateral disease showed that there were 30 children with favorable outcomes in their ET eyes and unfavorable outcomes in their CM eyes (discordant pairs), and 17 children with unfavorable outcomes in ET eyes and favorable outcomes in CM eyes. This difference approaches but does not reach statistical significance (P=0.06). Figure 2 provides the distribution of 6-year grating acuity outcomes by treatment assignment, for randomized eyes.

Table 2.

Six-year grating acuity outcome for randomized patients*

| Eyes Treated at High-Risk Prethreshold | Conventionally Managed Eyes | χ2 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral | 252**(18.3) | 252**(23.4) | 3.60 | 0.06@ |

| Asymmetric | 36^ (16.7) | 29^^(17.2) | 0.01 | 0.95 |

| Total | 288 (18.1) | 281 (22.8) | 3.09 | 0.08 |

Data are presented as number (percent unfavorable) unless otherwise indicated.

Less than 260 because of inability to perform Teller acuity test.

Less than 38 because of inability to perform Teller acuity test.

Less than 31 because of inability to perform Teller acuity test.

Based on discordant pairs (30 infants with favorable outcomes in earlier-treated eyes and unfavorable outcomes in conventionally managed eyes; 17 infants with unfavorable outcomes in earlier-treated eyes and favorable outcomes in conventionally managed eyes).

Figure 2.

Distribution of grating acuity outcomes for randomized eyes by treatment assignment. Normal = ≥ 13 cycles/degree; Below Normal = <13 cycles/degree to ≥ 6.4 cycles/degree; Poor = measurable acuity <6.4 cycles/degree; Blind/Low Vision = can detect only the 2.2-cm-wide stripes on the Low Vision Teller acuity card at any distance and at any location in the visual field, light percepti on only, or no light perception. Visual acuities in the Poor and Blind/Low Vision categories were classified as unfavorable outcomes.

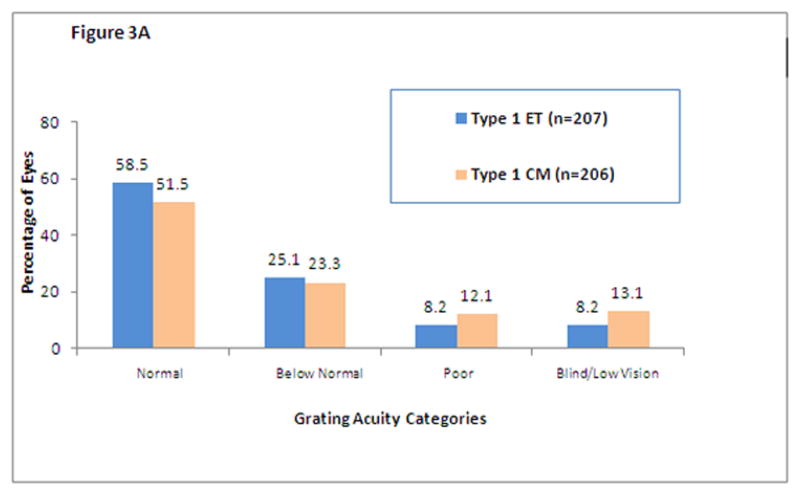

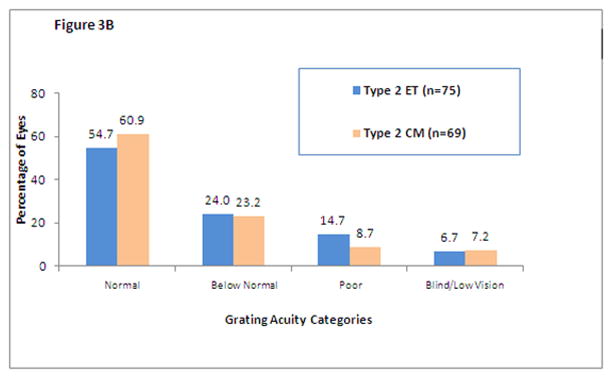

Analysis of the grating acuity data using Type 1 and Type 2 categories, as proposed in the initial ETROP results publication,11 is shown in Table 3 for eyes that were high risk based on the RM-ROP2 algorithm.(1) Type 1 high-risk prethreshold eyes that were treated early had a significantly lower rate of unfavorable outcomes (16.4%) than did Type 1 eyes that were managed conventionally (25.2%) (P=0.004). In contrast, Type 2 eyes that were high-risk showed a higher, but not statistically different, percentage of unfavorable outcomes in ET eyes (21.3%) than in CM eyes (15.9%) (P=0.29).

Table 3.

Six-year Grating Acuity Outcome for Randomized Patients by High-Risk Prethreshold ROP

| ROP | No. of Eyes (% Unfavorable) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ET Eyes | CM Eyes | ||

| Type 1 | 207 (16.4) | 206 (25.2) | .004 |

| Type 2 | 75 (21.3) | 69 (15.9) | .29 |

Abbreviations: CM, conventional management; ET, early treatment (treated at high-risk prethreshold).

Figure 3 shows the distribution of grating acuity scores for eyes that had high-risk prethreshold ROP. Results are shown for ET and CM Type 1 eyes (Figure 3A) and Type 2 eyes (Figure 3B). The data clearly indicate that there is a benefit of early treatment in Type 1 eyes but not in Type 2 eyes.

Figure 3.

Distribution of grating acuity outcomes for randomized eyes with Type 1(Figure 3A) and Type 2 (Figure 3B) ROP by treatment assignments (early treatment (ET) or conventional management (CM)). Normal = ≥ 13 cycles/degree; Below Normal = <13 cycles/degree to ≥ 6.4 cycles/degree; Poor = measurable acuity <6.4 cycles/degree; Blind/Low Vision = can detect only the 2.2-cm-wide stripes on the Low Vision Teller acuity card at any distance and at any location in the visual field, light perception only, or no light perception. Visual acuities in the Poor and Blind/Low Vision categories were classified as unfavorable outcomes.

Table 4 presents the discordant pairs for grating acuity outcome at 6 years for subgroups of children with bilateral high-risk prethreshold ROP by ICROP category, RM-ROP2 risk, and Type1/Type2 disease. The greatest benefit for early treatment was seen in eyes with Zone I, stage 3, with or without plus disease. The benefit of early treatment was observed for all risk categories, but was most pronounced in children with 30% to <45% risk for unfavorable outcome. This analysis also shows a significant benefit of early treatment for eyes with Type 1 disease, but not for eyes with Type 2 disease.

Table 4.

Grating Acuity at 6 Years for Children Who Had Bilateral High-Risk Prethreshold ROP by ICROP Category, RM-ROP2 Risk, and ROP status

| Both Eyes | No. (% Unfavorable) | Discordant Pairs, No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET Eyes | CM Eyes | Aa | Bb | |

| ICROP classification | ||||

| ZI S3 +/− | 23 (8.7) | 23 (52.2) | 10 | 0 |

| ZI S1/2 + | 7 (57.1) | 7 (42.9) | 0 | 1 |

| ZI S1/2 − | 63 (22.2) | 63 (17.5) | 5 | 8 |

| ZII S3 + | 97 (13.4) | 97 (18.6) | 10 | 5 |

| ZII S3 − | 3 (0.0) | 3 (0.0) | 0 | 0 |

| ZII S2 + | 31 (22.6) | 31 (29.0) | 3 | 1 |

| RM-ROP2 risk, rate of favorable outcome, % | ||||

| 0.15 to <0.30 | 94 (17.0) | 94 (20.2) | 10 | 7 |

| 0.30 to <0.45 | 69 (13.0) | 69 (23.2) | 10 | 3 |

| ≥0.45 | 68 (23.5) | 68 (29.4) | 9 | 5 |

| ROP Status | ||||

| Type 1 | 180 (16.7) | 180 (26.1) | 25 | 8 |

| Type 2 | 66 (21.2) | 66 (16.7) | 5 | 8 |

Abbreviations: CM, conventional management; ET, early treatment (treated at high-risk prethreshold); ICROP, International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ROP); RM-ROP2, risk model of ROP. S, stage; ZI/II, zone I/II; +/− indicates that plus may or may not be present ; + indicates presence of plus disease, ;− indicates the absence of plus disease,.

For group A, ET eyes had a favorable outcome and CM eyes had an unfavorable outcome.

For group B, ET eyes had an unfavorable outcome and CM eyes had a favorable outcome.

Discussion

The results of grating acuity assessment of early treated versus conventionally managed eyes with high-risk prethreshold ROP at age 6 years in the ETROP Study are consistent with the results of ETDRS recognition acuity assessment at 6 years,3 indicating a clear benefit for early treatment in eyes with Type 1 high-risk prethreshold ROP, but not in eyes with Type 2 high-risk prethreshold ROP. In eyes with Type 1 ROP, the rate of unfavorable grating acuity outcomes (i.e., grating acuity <6.4 cycles/deg) was 16.4% in early-treated eyes compared to 25.2% in conventionally-managed eyes (P=0.004). In contrast, the rate of unfavorable outcomes in eyes with Type 2 high-risk prethreshold ROP was greater in early-treated compared with conventionally-managed eyes (21.3% vs 15.9%)

The original design of the ETROP Study involved randomization of high-risk prethreshold eyes to either early treatment or conventional management. The study showed a clear benefit for early treatment of high-risk prethreshold eyes3. We also identified in 2003 that eyes could be segregated into 2 types according to the International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ICROP) characteristics. Eyes with Type 1 characteristics should be treated early and eyes with Type 2 characteristics could be observed, and treated if progression to Type 1 occurred (see Table 1). The majority of Type 2 eyes have ROP that regresses and does not require treatment. The results for grating acuity at age 6 years support these earlier recommendations. The results for grating acuity also are consistent with those reported for ETDRS acuity (optotype acuity) at age 6 years. However, the grating acuity results differ from the grating acuity results at age 9 months when a statistically significant difference was noted between ET and CM eyes. This is most likely due to dramatic visual development that occurs in the young child and ability to detect more subtle differences at the older age.

The present report has strengths and limitations. The first strength is that grating acuity data could be obtained from nearly all study eyes. There were only 10 (3.4%) of 298 early-treated and 10 (3.4%) of 291 conventionally-managed eyes for which grating acuity score was not available. A second strength of the present study is the masking of the visual acuity testers to the treatment status and the current retinal status of each eye. A final strength is the high follow-up rate (92.4%), 6 years after their enrollment in the study, for the 370 surviving study participants. A disadvantage of assessment of grating acuity is that in certain conditions that reduce optotype acuity (e.g., amblyopia,12 age-related maculopathy,13 and retinal residua of ROP14 ), grating acuity results may underestimate the loss in optotype acuity.

In conclusion, the grating acuity results at 6 years of age in children enrolled in the ETROP Study shows an enduring benefit for early treatment for most eyes with ROP. However, this benefit is present only for eyes with Type 1 disease. On the one hand, looking at all eyes in the study, early treatment did not reach statistical significance when grating acuity was assessed, but when eyes were distinguished by Type 1 or 2 characteristics, Type 1 eyes showed a significant benefit for grating acuity outcome, but Type 2 eyes did not. This finding supports the findings of the ETDRS acuity outcome results3, making careful observation and identification of ICROP characteristics even more important as one contemplates whether laser ablation should be performed.

Acknowledgments

Supported by Cooperative Agreements (5U10 EY12471 and 5U10 EY12472) with the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Bethesda, Maryland.

ETROP STUDY INVESTIGATORS

Writing Committee: Chair: Velma Dobson, PhD; Graham Quinn, MD, MSCE; C. Gail Summers, MD; Robert J. Hardy, PhD; Betty Tung, MS.; William V. Good, MD.

Stanford Center (Palo Alto, CA). Lucille Packard Children’s Hospital, Stanford University. Principal Investigator: Ashima Madan, MD; Study Center Coordinators: M. Bethany Ball, BS; Judith Y. Hall, RNC; Coinvestigator: William V. Good, M.D.

San Francisco Center (San Francisco, CA). California Pacific Medical Center, Oakland Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Francisco Medical Center. Principal Investigator: William V. Good, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Judith Gancasz; Coinvestigators: David Durand, MD; Terri Slagle, MD; Gordon Smith, MD.

Chicago Center (Chicago, IL). University of Illinois at Chicago Hospital and Medical Center. Principal Investigator: Michael Shapiro, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Nydia Santiago; Coinvestigators: Rama Bhat, MD; Lawrence Kaufman, MD; Marilyn Miller, MD; David Mittelman, MD.

Indianapolis Center (Indianapolis, IN). (Indiana University School of Medicine) James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children, Indiana University Hospital, Wishard Memorial Hospital, Methodist Hospital, Community Hospitals of Indianapolis. Principal Investigator: Daniel Neely, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Elizabeth A. Hynes, RN; Coinvestigator: David Plager, MD.

Louisville Center (Louisville, KY). Kosair Children’s Hospital, University of Louisville Hospital. Principal Investigator: Charles C. Barr, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Michelle Bottorff; Greg K. Whittington, PsyS; Coinvestigators: Peggy H. Fishman, MD, Paul J. Rychwalski, MD.

New Orleans Center (New Orleans, LA). Tulane University Medical Center, Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans. Principal Investigator: Robert A. Gordon, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Deborah S. Neff, LPN; Coinvestigators: James G. Diamond, MD; William L. Gill, MD.

Baltimore G Center (Baltimore, MD). University of Maryland Medical Systems, Mercy Medical Center, Franklin Square Hospital. Principal Investigator: Mark W. Preslan, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Kevin Powdrill; Coinvestigators: Kelly A. Hutcheson, MD; Eric Jones, MD; Scott M. Steidl, MD, DMA; Joanne Marie Waeltermann, MD.

Baltimore R Center, Baltimore, MD). Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Howard County General Hospital, Greater Baltimore Medical Center, St. Joseph Medical Center. Principal Investigator: Michael X. Repka, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Jennifer A. Shepard, NNP; Pamela Donahue, PA-C, ScD; Coinvestigators: Susan W. Aucott, MD; Mary Louise Z. Collins, MD; Maureen M. Gilmore, MD; James T. Handa, MD.

Boston Center (Boston, MA). Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Children’s Hospital Boston, New England Medical Center, Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Principal Investigator: Deborah K. VanderVeen, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Theresa Mansfield, RN; Brenda MacKinnon, RNC; Coinvestigators: Cynthia H. Cole, MD, MPH; Anthony Fraioli, MD; David Hunter, MD; O’Ine McCabe, MD; Robert Petersen, MD; Mitchell Brent Strominger, MD; Orthoptists: Sarah MacKinnon, OC(C), COMT; Rhiannon Johnson, OC(C); Mariette Tyedmers, CO.

Detroit Center (Detroit, MI). William Beaumont Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Michigan, St. John’s Hospital Detroit. Principal Investigator: John Baker, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Kristi Cumming, MSN; Pat Manatrey, RN; Coinvestigators: Mary P. Bedard, MD; Renato Casabar, MD; Antonio Capone, MD; Edward O’Malley, MD; Rajesh Rao, MD; John Roarty, MD; Michael Trese, MD; George Williams, MD.

Minneapolis Center (Minneapolis, MN). Fairview University Medical Center, Children’s Health Care, Minneapolis, Hennepin County Medical Center. Principal Investigator: C. Gail Summers, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Sally Cook, BA; Ann Holleschau, BA; Molly Maxwell, RN; Coinvestigators: Stephen P. Christiansen, MD; David Brasel, MD.

St. Louis Center (St. Louis, MO). Cardinal Glennon Children’s Medical Center, St. Mary’s Health Center. Principal Investigator: Bradley V. Davitt, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Linda Breuer, LPN; Coinvestigators: Oscar Cruz, MD; William Keenan, MD; Greg Mantych, MD, Gregg Lueder, MD.

North Carolina Center (Durham, NC). Duke University Medical Center. Principal Investigator: Sharon Freedman, MD; Co-principal Investigator: David Wallace, MD, MPH; Study Center Coordinators: Lori Hutchins Parkman, RN; Sarah K. Jones; Coinvestigators: Laura Enyedi, MD; Ricki F. Goldstein, MD.

Buffalo Center (Buffalo, NY). Women’s and Children’s Hospital of Buffalo, Sisters of Charity Hospital. Principal Investigator: James D. Reynolds, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Kristine Ziemann, RN, BSN; Coinvestigators: George P. Albert, MD; Steven Awner, MD; Rita Ryan, MD.

Long Island/Westchester Center (New York). Stony Brook University Hospital, Westchester Medical Center. Principal Investigator: Pamela Ann Weber, MD; Co-principal Investigator: Marc Horowitz, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Cherylene Behrendt; Adriann Combs; Natalie Dweck, RN; Coinvestigators: Richard Koty, MD; Edmund LaGamma, MD; Maury Marmor, MD.

New York Center (New York, NY). New York Presbyterian Hospital, Columbia Campus, New York Presbyterian Hospital, Cornell Campus. Principal Investigator: John Flynn, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Osode Coki, RNC, BSN; Coinvestigators: Michael Chiang, MD, MPH; Steven Kane, MD; Alfred Krauss, MD; Thomas C. Lee, MD, PhD; Robert F. Lopez, MD; Richard Polin, MD.

Rochester/Syracuse Center (New York). University of Rochester Medical Center, Crouse-Irving Memorial Hospital. Principal Investigator: Dale L. Phelps, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Cassandra Horihan, MS; Jane Phillips; Coinvestigators: Gary Markowitz, MD; Walter Merriam, MD; Leon-Paul Noel, MD; Donald Tingley, MD; Matthew Gearinger, MD.

Columbus Center (Columbus, Ohio). Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Principal Investigator: Gary L. Rogers, MD; Co-principal Investigator: Don Bremer, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Rae Fellows, MEd; Sharon Klamfoth, LPN; Coinvestigators: Brian Arthur, MD; Cybil Bean Cassady, MD; Richard Golden, MD; Mary Lou McGregor, MD.

Oklahoma City Center (Oklahoma City, OK). University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center; Dean A. McGee Eye Institute. Principal Investigator: R. Michael Siatkowski, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Cheryl Harris, COA; Vanessa Yazdanipanah; Coinvestigators: Reagan H. Bradford, MD; Robert E. Leonard, MD; Mary Anne McCaffree, MD.

Portland Center (Portland, OR). Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health and Science University. Principal Investigator: David T. Wheeler, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Nancy Dolphin, RN; Coinvestigators: Earl A. Palmer, MD; Ann Stout, MD; Brian Nichols, MD; David Epley, MD.

Philadelphia Center (Philadelphia, PA). The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania Hospital. Principal Investigator: Graham E. Quinn, MD, MSCE; Study Center Coordinators: Jamie G. Koh, RN, MSN, CCRC; Marianne Letterio, RN, BSN; Coinvestigators: Soraya Abbasi, MD; Jane C. Edmond, MD; Brian J. Forbes, MD, PhD; Albert M. Maguire, MD; Monte D. Mills, MD; Eric A. Pierce, MD; Terri L. Young, MD; Stephanie Davidson, MD.

Pittsburgh Center (Pittsburgh, PA). Magee-Women’s Hospital. Principal Investigator: Kenneth Cheng, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Janice Kelchner-Cheng, RN; Judith Jones, RNC, BSN; Coinvestigators: Robert Bergren, MD; Bernard Doft, MD; Louis Lobes, MD; Karl Olsen, MD.

Charleston Center (Charleston, SC). Medical University of South Carolina. Principal Investigator: Richard A. Saunders, MD; Co-principal Investigator: Dilip Purohit, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Linda Stevens, RN; Vision Tester: Kimberly Lenhart.

Houston Center (Houston, TX). Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children’s Hospital, Texas Woman’s Hospital, Ben Taub General Hospital. Principal Investigator: David K. Coats, MD; Study Center Coordinators: Michele L. Parker, COA; Maria Castanes, MPH; Alison Brown; Coinvestigators: Jane Edmond, MD; Joseph Garcia-Prats, MD; Eric Holz, MD; W. Scott Jarriel, MD; Karen Johnson, MD; George Mandy, MD; Evelyn A. Paysee, MD; A. Melinda Rainey, MD; Paul G. Steinkuller, MD; Kimberly G. Yen, MD;.

San Antonio Center (San Antonio, TX). University of Texas Health Science Center, University Hospital, Christus Santa Rosa Children’s Hospital. Principal Investigator: John P. Stokes, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Yolanda Trigo, COT; Coinvestigators: Alice K. Gong, MD; W.A.J. van Heuven, MD.

Salt Lake City Center (Salt Lake City, UT). University of Utah Health Science Center, Primary Children’s Medical Center. Principal Investigator: Robert Hoffman, MD; Study Center Coordinator: Susan Bracken, RN; Deborah Y. Harrison, MS; Coinvestigators: Paul Bernstein, MD; Jerald King, MD; Michael Teske, MD.

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD. Program Officer: Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH (June, 2001-Present); Richard L. Mowery, PhD (October, 2000-May, 2001); Donald F. Everett, MA (September, 1999-September, 2000).

Study Headquarters: Smith-Kettlewell Eye Research Institute, San Francisco, CA. Principal Investigator: William V. Good, MD; Project Coordinator: Michelle Quintos, BA.

Coordinating Center: School of Public Health, Coordinating Center for Clinical Trials, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX. Principal Investigator: Robert J. Hardy, PhD; Coinvestigators: Betty Tung, MS, ; Coordinating Center Staff: Gordon Tsai, MS.

Vision Testing Center: University of Arizona, College of Medicine, Tucson, AZ. Principal Investigator: Velma Dobson, PhD; Vision Testers: Deborah D. Hargadon, Jeffrey Wood; Coinvestigators: Graham E. Quinn, MD, Erin M. Harvey, PhD.

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee: Chair: John Connett, PhD; Members: Edward F. Donovan, MD; Argye Hillis, PhD; Jonathan M. Holmes, MD; Joseph M. Miller, MD; Carol R. Taylor, RN, CSFN, PhD; Ex-officio Members: William V. Good, MD; Robert J. Hardy, PhD; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH.

Executive Committee: Permanent Members: Chair: William V. Good, MD; Robert J. Hardy, PhD; Velma Dobson, PhD; Earl A. Palmer, MD; Dale L. Phelps, MD; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH.

Executive Committee: Elected Members: W.A.J. van Heuven, MD (2000–2001; 2004–2007); Charles Barr, MD (2001–2002); Michael Gaynon, MD (2002–2003); Michael Shapiro, MD (2003–2004); David Wallace, MD (2007–2008); Bradley V. Davitt, MD (2008-Present); Rae Fellows, MEd (2000–2001; 2006-Present); Judith Jones, RNC, BSN (2001–2002); Kristi Cumming, MSN (2002–2003); Deborah S. Neff, LPN (2003–2004); Jennifer A. Shepard, NNP (2004–2006); Nancy Dolphin, RN (2006-Present).

Editorial Committee: Chair: William V. Good, MD; Robert J. Hardy, PhD; Velma Dobson, PhD; Earl A. Palmer, MD; Dale L. Phelps, MD; Michelle Quintos, BA; Betty Tung, MS.

Footnotes

The authors have no affiliation with or financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in the paper (e.g., employment, consultancies, stock ownership, honoraria), with the exception of Velma Dobson, PhD, who has received royalties from the sale of Teller acuity cards.

References

- 1.Hardy RJ, Palmer EA, Dobson V, Summers CG, Phelps DL, Quinn GE, Good WV, Tung B. Risk analysis of prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003 Dec;121(12):1697–701. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferris FL, 3rd, Kassoff A, Bresnick GH, Bailey I. New visual acuity charts for clinical research. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982 Jul;94(1):91–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Final visual acuity results in the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jun;128(6):663–71. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teller DY, McDonald MA, Preston K, Sebris SL, Dobson V. Assessment of visual acuity in infants and children: the acuity card procedure. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1986 Dec;28(6):779–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1986.tb03932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dobson V, Quinn GE, Biglan AW, Tung B, Flynn JT, Palmer EA. Acuity card assessment of visual function in the cryotherapy for retinopathy of prematurity trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990 Sep;31(9):1702–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardy RJ, Good WV, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, Tung B. Multicenter trial of early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity: study design. Control Clin Trials. 2004 Jun;25(3):311–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Multicenter trial of cryotherapy for retinopathy of prematurity. Snellen visual acuity and structural outcome at 5 1/2 years after randomization. Cryotherapy for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996 Apr;114(4):417–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130413008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trueb L, Evans J, Hammel A, Bartholomew P, Dobson V. Assessing Visual Acuity of Visually Impaired Children Using the Teller Acuity Card Procedure. Am Orthoptic J. 1992;42:149–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hargadon DD, Wood J, Twelker JD, Harvey EM, Dobson V. Recognition acuity, grating acuity, contrast sensitivity, and visual fields in 6-year-old children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010 Jan;128(1):70–4. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy R, Davis B. American Statistical Association: 1989 Proceedings of Biopharmaceutical Section. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association; 1989. The design, analysis and monitoring of an ophthalmological clinical trial; pp. 248–53. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Early Treatment For Retinopathy Of Prematurity Cooperative G. Revised indications for the treatment of retinopathy of prematurity: results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003 Dec;121(12):1684–94. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friendly DS, Jaafar MS, Morillo DL. A comparative study of grating and recognition visual acuity testing in children with anisometropic amblyopia without strabismus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990 Sep 15;110(3):293–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White JM, Loshin DS. Grating acuity overestimates Snellen acuity in patients with age-related maculopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 1989 Nov;66(11):751–5. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198911000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dobson V, Quinn G, Tung B, et al. Comparison of Recognition and Grating Acuities in Very-Low-Birth-Weight Children With and Without Retinal Residua of Retinopathy of PRematurity. Invst Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:692–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]