Abstract

Background

The Boston Naming Test (BNT) is a commonly used neuropsychological test of confrontation naming that aids in determining the presence and severity of dysnomia. Many short versions of the original 60-item test have been developed and are routinely administered in clinical/research settings. Because of the common need to translate similar measures within and across studies, it is important to evaluate the operating characteristics and agreement of different BNT versions.

Methods

We analyzed longitudinal data of research volunteers (n = 681) from the University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center longitudinal cohort.

Conclusions

With the notable exception of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) 15-item BNT, short forms were internally consistent and highly correlated with the full version; these measures varied by diagnosis and generally improved from normal to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to dementia. All short forms retained the ability to discriminate between normal subjects and those with dementia. The ability to discriminate between normal and MCI subjects was less strong for the short forms than the full BNT, but they exhibited similar patterns. These results have important implications for researchers designing longitudinal studies, who must consider that the statistical properties of even closely related test forms may be quite different.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease; Cognitive impairment; Cohort studies; Clinical diagnosis; Clinical neuropsychology; Dementia and neuropsychology; Design, analysis, interpretation of data; Longitudinal assessment; Mild cognitive impairment and dementia; Neuropsychiatric assessment

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by memory deficits and impairment in the ability to perform activities of daily living. Another hallmark neurological sign associated with AD is dysnomia (also known as amnesic aphasia and nominal aphasia), as reflected in word-finding and object-naming difficulty [1], which has been shown to occur even in preclinical stages of AD [2] and likely represents a loss of semantic knowledge [3]. Dysnomia is often assessed with measures of confrontation naming, a task requiring the production of a word corresponding to a visually presented stimulus. The Boston Naming Test (BNT) is one of the most frequently used measures of confrontation naming [4]. The full BNT consists of 60 black and white line drawings of various items roughly ordered by increasing difficulty. A period of 20 s is allowed for a spontaneously generated response. If no response or an incorrect response is provided, the examiner may offer semantic or phonemic cues to assist with name retrieval. The full 60-item version can be rather lengthy in terms of administration time, often making it difficult for severely impaired persons to complete the test. In clinical trials and research investigations, time is at a premium and longer assessments are often not administered [see for example 5].

The first attempt to standardize a brief measure for the diagnosis of AD was the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) neuropsychological battery [6], which included a 15-item version of the BNT (BNT-15). Items from the 60-item BNT were chosen to represent each of 3 word frequency categories equally: high, medium, and low [7]. Persons with AD have been shown to perform significantly below persons with intact cognitive functioning on each test from the CERAD battery, including the BNT-15 [8].

Since the CERAD BNT-15 has been derived, multiple short forms of the BNT have been developed and subsequently used in different studies [9--12]. Each BNT version performs differently in terms of its relationship with the 60-item BNT and its ability to discriminate between cognitively normal and impaired participants [9--11, 13]. For example, a 30-item test that was empirically derived by selecting those items with the optimal discrimination between AD and cognitively normal subjects [11] was compared with short forms comprising the 30 even-numbered (Even30) and the 30 odd-numbered (Odd30) items from the full BNT [10]. Currently, the Odd30 version is being used in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center’s Uniform Data Set (NACC UDS) administered by all Alzheimer’s Disease Centers [14]; this will be replaced by the Multilingual Naming Test (MiNT) [15] in the upcoming UDS 3.0 (anticipated fall 2014).

These short-form-version-based discrepancies motivate the current investigation. The CERAD BNT-15 has been used frequently in longitudinal studies of aging and AD (e.g.,University of Kentucky Alzheimer’s Disease Center (UK-ADC) longitudinal cohort [16], Nun Study [17], Religious Orders Study [18], Einstein Aging Study [19], Oregon Brain Aging Study [20], and Honolulu Asia Aging Study [21]), and it has just as often been replaced by other versions of the BNT during the course of the study. Adoption of alternative forms and measures during longitudinal studies is motivated by both practical (e.g., copyright issues or funding agency mandates) and scientific (e.g., more sensitive and specific measures become available) concerns. However, the use of different measures or different forms of the same measure to represent a particular construct (like multiple BNT versions or replacing the BNT with an alternative measure, as in NACC) poses difficulties when comparing results across studies or within a longitudinal study that has transitioned between versions.

In order to gauge the feasibility of aggregating data from alternate BNT forms over time, we examined performance characteristics of the BNT with the data from participants enrolled in the UK-ADC longitudinal cohort. The UK-ADC adopted the 60-item BNT in 2005, after the CERAD BNT-15 had been administered previously from 1989 to 2005 [16]. To determine the ability of each BNT short form to discriminate between cognitively normal and impaired participants, the diagnostic accuracy of each 15-item and 30-item form was examined in groups of individuals classified as having normal cognitive functioning, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or dementia. For the purposes of replicating previous analyses within a large and longitudinally followed sample, the current analysis also includes correlations between each short form and the full 60-item BNT. Internal consistencies of each short form are also reported.

Methods

Participants

The participants were research volunteers in the UK-ADC longitudinal cohort, a study of older adults established in 1985 [16, 22]. The University of Kentucky’s Institutional Review Board approved all research activities. The cohort used in this report included 681 people aged ≥60 years who had been enrolled in the UK-ADC cohort between 1989 and 2010 and had been administered the full 60-item BNT at least once. Since the 60-item BNT has not been implemented until 2005, those enrolled prior to 2005 do not have data from the 60-item BNT at their baseline assessment. Accordingly, baseline data for our analytical purposes were defined as the first available administration of the 60-item BNT. Of the 681 participants with 60-item BNT data, 270 completed the 60-item BNT at their first visit. The analytical baseline data of the remaining 411 participants were collected on follow-up visits.

Clinical Cognitive Diagnosis

Diagnosis was determined by a clinical consensus involving a team of neurologists and neuropsychologists in accordance with the NACC UDS protocol (Form D1: Clinical Diagnosis – Cognitive Status and Dementia) [23].

Boston Naming Test

The BNT was administered following the instructions provided as part of a standard neuropsychological battery of tests [14]. All subjects began with item 1 and proceeded until item 60 in ascending order. Each item was scored ‘1’ if correctly answered within 20 s with or without a stimulus cue and ‘0’ otherwise. The test was discontinued if 6 consecutive items were named incorrectly, regardless of whether or not stimulus cues were given.

Items included in each BNT short version are listed in Appendix 1. Mack et al. [10] created four 15-item short versions by assigning the 60 items to 4 sets based on order (Mack15.1–15.4). The 4 Mack 15-item versions were also combined into two 30-item versions: Mack 30A (Mack15.1 plus Mack15.2) and Mack 30B (Mack15.3 plus Mack15.4) [24]. Williams et al. [11] selected those 30 items (Williams30) demonstrating the largest mean differences between AD patients and normal controls. Lansing et al. [9] used a stepwise discriminant analysis to empirically derive a new gender-neutral 15-item short form (Lansing15) with maximum discriminability between 325 AD patients and 719 normal controls. Saxton et al. [12] developed two 30-item short forms of equivalent difficulty by dividing the 60 items based on the performance of community-dwelling adults aged ≥65 (Saxton30.A and Saxton30.B). In addition to these versions, we evaluated Odd30 (currently used in NACC), Even30, and the CERAD BNT-15. Each shortened version was constructed from the full 60-item BNT.

Statistical Analysis

Means among the shortened versions (by diagnostic group) were compared with Tukey’s honestly significant difference post hoc test using repeated measures analysis of variance. Correlations were examined between each of the shortened versions and the full 60-item BNT using the Spearman rank order correlation coefficient. Cronbach’s α coefficient was obtained to assess internal consistency for all BNT versions. Coefficients ≥0.7 were regarded as indicating acceptable levels of validity and reliability [25]. For each of the 2 types of diagnosed cognitive impairment (MCI and dementia), we used logistic regression models to predict impairment versus normal cognition separately with scores from each BNT version. For each prediction, both an unadjusted model and one adjusted for age, gender, years of education, and dichotomized race (white or others) were employed. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUC) statistic was used to evaluate diagnostic accuracy. Confidence intervals for the AUC were constructed using 2,000 bootstrap replicates. All statistical analyses were carried out with R version 3.0.2 [26].

Results

The characteristics of the 681 individuals during their first administration of the 60-item BNT are shown in table 1. Of the 681 individuals, 432 (63.4%) were women; 632 (92.8%) were white. At the time of their first 60-item BNT assessment, the participants’ mean age was 75.9 years (range 60–97). The participants had a mean 15.8 years of education (range 5–28). 506 (74.3%) were diagnosed as cognitively normal, 105 (15.4%) with MCI, and 70 (10.3%) with dementia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 681 individuals when the 60-item BNT was first administered

| Characteristics | |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Men | 249 (36.6) |

| Women | 432 (63.4) |

| Mean age ± SD, years | 75.9 ± 7.5 |

| Mean numbers of years of education ± SD | 15.8 ± 2.8 |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 632 (92.8) |

| Others | 49 (7.2) |

|

| |

| Type of diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Normal | 506 (74.3) |

| MCI | 105 (15.4) |

| Nonamnestic MCI | 8 |

| Amnestic MCI | 97 |

| Dementia | 70 (10.3) |

| Probable AD | 59 |

| Possible AD | 4 |

| Vascular dementia | 3 |

| Dementia with Lewy bodies | 1 |

| Progressive supranuclear palsy | 1 |

| Parkinson’s disease dementia | 1 |

| Dementia of unknown etiology | 1 |

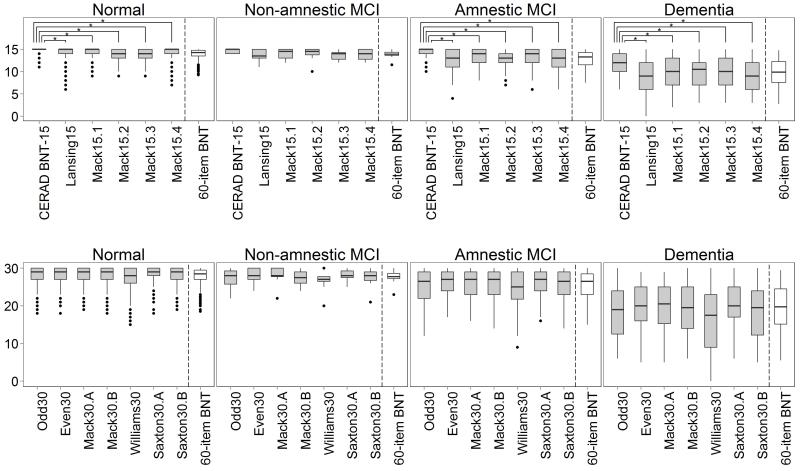

Figure 1 shows the boxplots of the short versions within each diagnostic category. To compare between the full and short versions, the total score of the 60-item BNT was divided by 4 for the 15-item short versions and by 2 for the 30-item short versions. Except for the CERAD BNT-15, the patterns of the various 15-item scores reflect that of the 60-item BNT. The mean of the CERAD BNT-15 was significantly higher than that of other 15-item versions in every type of diagnosis (all Tukey’s honestly significant difference test p values <0.001). Meanwhile, the patterns of the 30-item score means reflected that of the 60-item BNT score except for Williams30. The mean of Williams30 was more likely to be lower than that of other 30-item versions in those with cognitive impairment (Appendix 2).

Fig. 1.

Boxplots of the 15-item short forms (a) and the 30-item short forms (b) of the BNT for each type of diagnosis. * p < 0.001.

Again, other than the CERAD BNT-15 (r = 0.689), Spearman’s correlation coefficients between each of the short versions and the 60-item BNT were high in all diagnostic groups, ranging from 0.823 to 0.971. The correlations between the CERAD BNT-15 and the 60-item BNT were significantly lower than those of other short versions (p = 0.004) even by type of diagnosis (table 2). The 60-item BNT had a high Cronbach’s α coefficient when all data were used and when restricted to each diagnostic group (α between 0.839 and 0.958). The CERAD BNT-15 had markedly lower Cronbach’s α coefficients in the cognitively normal group (α = 0.386) compared with the other versions. The α in the normal group (between 0.507 and 0.782, excluding the CERAD BNT-15 and the 60-item BNT) trended lower than in the MCI (between 0.667 and 0.880) and dementia groups (between 0.831 and 0.944), likely a result of a ceiling effect for these individuals.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients (r) between each of the short forms of the BNT and the full 60-item version and Cronbach’s α of all versions

| Version | All |

Normal |

MCI |

Dementia |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | α | r | α | r | α | r | α | |

| CERAD BNT-15 | 0.689 | 0.758 | 0.593 | 0.386 | 0.735 | 0.612 | 0.871 | 0.797 |

| Lansing15 | 0.831 | 0.866 | 0.733 | 0.637 | 0.885 | 0.779 | 0.936 | 0.889 |

| Mack15.1 | 0.823 | 0.827 | 0.726 | 0.525 | 0.900 | 0.689 | 0.940 | 0.856 |

| Mack15.2 | 0.843 | 0.775 | 0.783 | 0.507 | 0.850 | 0.667 | 0.934 | 0.831 |

| Mack15.3 | 0.838 | 0.799 | 0.785 | 0.522 | 0.834 | 0.716 | 0.948 | 0.846 |

| Mack15.4 | 0.862 | 0.840 | 0.773 | 0.661 | 0.927 | 0.782 | 0.957 | 0.852 |

|

| ||||||||

| Odd30 | 0.936 | 0.905 | 0.899 | 0.738 | 0.961 | 0.863 | 0.986 | 0.922 |

| Even30 | 0.930 | 0.889 | 0.898 | 0.692 | 0.937 | 0.818 | 0.969 | 0.916 |

| Mack30.A | 0.933 | 0.892 | 0.900 | 0.686 | 0.954 | 0.816 | 0.980 | 0.915 |

| Mack30.B | 0.945 | 0.902 | 0.914 | 0.748 | 0.965 | 0.854 | 0.986 | 0.921 |

| Williams30 | 0.971 | 0.925 | 0.955 | 0.782 | 0.979 | 0.880 | 0.986 | 0.944 |

| Saxton30.A | 0.932 | 0.891 | 0.890 | 0.702 | 0.957 | 0.842 | 0.977 | 0.914 |

| Saxton30.B | 0.948 | 0.903 | 0.921 | 0.726 | 0.958 | 0.841 | 0.987 | 0.923 |

|

| ||||||||

| 60-item BNT | – | 0.947 | – | 0.839 | – | 0.915 | – | 0.958 |

Tables 3 and 4 show the AUCs for each BNT version based on BNT alone (unadjusted) and with adjustment for age, gender, years of education, and race, respectively. Compared with other versions, the CERAD BNT-15 demonstrated a poorer ability to discriminate between cognitively normal participants and participants with MCI and dementia, with unadjusted AUCs of 0.580 (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.526--0.634) and 0.852 (95% CI 0.798--0.906), respectively. These AUCs improved when logistic regression models were adjusted for age, gender, years of education, and race; however, the CERAD BNT-15 still had lower AUCs than the other versions. While not statistically significantly different from the other high-performing short forms, the Mack15.4 had the greatest nominal ability to discriminate between cognitively normal participants and those with MCI, with an unadjusted AUC of 0.703 (95% CI 0.645--0.761) and adjusted AUC of 0.782 (95% CI 0.733--0.831). Similarly, the Even30 had the best ability to discriminate participants with dementia from participants with normal cognitive function, with an unadjusted AUC of 0.930 (95% CI 0.899--0.961) and an adjusted AUC of 0.940 (95% CI 0.911--0.969).

Table 3.

AUCs by type of diagnosis (vs. normal) using an unadjusted model

| Version | MCI (95% CI) | Dementia (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| CERAD BNT-15 | 0.580 (0.526–0.634) | 0.852 (0.798–0.906) |

| Lansing15 | 0.689 (0.631–0.747) | 0.915 (0.876–0.953) |

| Mack15.1 | 0.668 (0.609–0.727) | 0.917 (0.882–0.953) |

| Mack15.2 | 0.657 (0.598–0.717) | 0.894 (0.852–0.936) |

| Mack15.3 | 0.627 (0.567–0.686) | 0.887 (0.842–0.933) |

| Mack15.4 | 0.703 (0.645–0.761) | 0.914 (0.875–0.953) |

|

| ||

| Odd30 | 0.700 (0.642–0.759) | 0.911 (0.870–0.952) |

| Even30 | 0.663 (0.601–0.725) | 0.930 (0.899–0.961) |

| Mack30.A | 0.679 (0.618–0.740) | 0.927 (0.895–0.959) |

| Mack30.B | 0.692 (0.632–0.752) | 0.916 (0.875–0.957) |

| Williams30 | 0.681 (0.620–0.742) | 0.922 (0.885–0.959) |

| Saxton30.A | 0.692 (0.632–0.752) | 0.919 (0.882–0.957) |

| Saxton30.B | 0.680 (0.621–0.740) | 0.923 (0.887–0.960) |

|

| ||

| 60-item BNT | 0.694 (0.633–0.754) | 0.929 (0.894–0.963) |

Table 4.

AUCs by type of diagnosis (vs. normal) using a logistic regression model adjusted for age, gender, years of education, and race

| Version | MCI (95% CI) | Dementia (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| CERAD BNT-15 | 0.733 (0.680–0.786) | 0.885 (0.836–0.935) |

| Lansing15 | 0.768 (0.717–0.818) | 0.930 (0.895–0.964) |

| Mack15.1 | 0.763 (0.711–0.815) | 0.923 (0.887–0.958) |

| Mack15.2 | 0.760 (0.713–0.807) | 0.914 (0.879–0.950) |

| Mack15.3 | 0.734 (0.682–0.785) | 0.902 (0.860–0.943) |

| Mack15.4 | 0.782 (0.733–0.831) | 0.933 (0.900–0.966) |

|

| ||

| Odd30 | 0.776 (0.726–0.826) | 0.921 (0.884–0.959) |

| Even30 | 0.761 (0.712–0.811) | 0.940 (0.911–0.969) |

| Mack30.A | 0.770 (0.722–0.818) | 0.936 (0.907–0.966) |

| Mack30.B | 0.772 (0.723–0.820) | 0.930 (0.895–0.966) |

| Williams30 | 0.772 (0.724–0.821) | 0.932 (0.896–0.967) |

| Saxton30.A | 0.778 (0.730–0.825) | 0.932 (0.898–0.966) |

| Saxton30.B | 0.766 (0.716–0.816) | 0.933 (0.900–0.965) |

|

| ||

| 60-item BNT | 0.776 (0.727–0.824) | 0.939 (0.907–0.970) |

Discussion

The BNT has multiple forms, each with its own properties regarding the actual construct that is being measured and the ability to aid in discriminating cognitive functioning. The current study evaluated the internal consistency and correlations between six 15-item short versions, seven 30-item short versions, and the full 60-item version of the BNT in participants from the UK-ADC longitudinal cohort. The diagnostic accuracy of each of the short forms was also evaluated across 3 clinical cognitive diagnoses. Four key findings arose from the analyses, which underscore the importance of measure selection.

First, the CERAD BNT-15 was likely to generate a higher absolute score than the other 15-item versions within each type of cognitive diagnosis, while Williams30 was likely to generate a lower score than the other 30-item versions, as previously described [9]. Our results are also consistent with Lansing et al. [9] in that both studies found that normal controls and demented patients scored significantly higher in the CERAD BNT-15 than in the 4 Mack15-item versions and the Lansing 15-item version. The CERAD BNT-15 is composed of 10 items of the first half and only 5 of the second half of the 60 BNT items, which generally increase in difficulty. This is an important point that likely explains the inability of the CERAD BNT-15 to discriminate between cognitively normal persons and those with MCI [27] as well as its poor performance relative to the other short forms. If the majority of the test items are easy, persons with very mild impairment are not likely to miss them. Items of greater difficulty pose a more significant challenge that is necessary to make finer discriminations between cognitively normal persons and those with MCI or early AD. It is also important to note that if the CERAD BNT-15 is used clinically to aid in staging AD severity, patients’ semantic ability will likely be overestimated.

Second, except for the CERAD BNT-15, high correlations were found between the results of the full 60-item BNT and all short versions. Mack15.4, among the 15-item short versions, and Williams30, among the 30-item versions, showed relatively high correlations with the full version and demonstrated consistency across the types of clinical diagnosis. In contrast, the CERAD BNT-15 had a poor correlation with the 60-item BNT (below 0.7) in cognitively normal subjects. Although correlations between the CERAD BNT-15 and the 60-item BNT were acceptable in the MCI (r = 0.73) and dementia (r = 0.87) groups, the CERAD BNT-15 still displayed the lowest correlation with the 60-item BNT among all of the short forms. Again, the fact that the item structure for the CERAD 15-item version does not appear comparable to the other short forms may have played a role in this finding.

Third, as expected, the full 60-item BNT had the highest Cronbach’s α (internal consistency) because it is sensitive to the number of items. Even with this consideration, the CERAD BNT-15 showed markedly low internal consistency in the normal group (α = 0.386), while all other short forms were at or above 0.507. Williams30 had a good internal consistency across the diagnoses compared with the other 30-item versions. All short forms were reliable within the MCI and dementia groups.

Lastly, according to the investigation of the AUCs, the CERAD BNT-15 had a poor diagnostic accuracy between cognitively normal participants and participants with MCI compared with the other versions. Although the accuracy improved when adjusted for age, gender, years of education, and race (26.4% improvement for MCI), the diagnostic accuracy (normal vs. MCI) among all short forms was poor. Nevertheless, the CERAD BNT-15 discriminated between cognitively normal participants and participants with dementia approximately as well as the other short versions. Our results are generally consistent with other findings in this regard. Given that the CERAD BNT-15 is composed of a much easier item set, most participants without advanced cognitive impairment (i.e., cognitively normal and MCI) will not miss many items. Cognitive decline to dementia is a process that occurs over many years, and subtle cognitive impairments will only be revealed when a person’s limits are sufficiently tested with more challenging items.

Also of note, the AUC of the 60-item BNT was only 0.694 (without covariate adjustment) when discriminating between cognitively normal participants and those with MCI; when covariate adjustment was added, it improved to 0.776. This is not surprising given that MCI presents in a variety of different ways, not all of which include deficits in confrontation naming. For future research endeavors, it will be important to recognize the variability in MCI cognitive presentations and underlying etiologies. Ideally, persons with MCI would not be aggregated into one group but would be separated by the type of MCI[28--31] or suspected etiology. Here, we aggregated 8 nonamnestic and 97 amnestic MCI subjects due to the relatively low number of nonamnestic individuals. When examining each MCI subset separately (data not shown), discriminating between nonamnestic MCI and cognitively normal subjects was more difficult, and the estimated confidence intervals for the corresponding AUCs were approximately 3 times the width. Results using only amnestic MCI participants were similar to those with aggregated MCI subjects.

All short BNT versions were able to discriminate well between cognitively normal participants and those with dementia, with covariate adjustments improving the discrimination ability. The short forms performed well compared to the full 60-item BNT for discriminating between cognitively normal participants and those with MCI; however, the capacity for discriminating MCI against normal cognition was noticeably weaker. For the purposes of clinical use, Mack15.4 performed well relative to the other forms while taking into account ease of administration. In particular, Mack15.4 obtained the highest AUC for discriminating between normal and MCI subjects in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, outperforming even the full 60-item BNT. It also performed well regarding discrimination between normal and dementia diagnoses and had the greatest separation between amnestic and nonamnestic MCI means (data not shown) among the 15-item tests. It must be reiterated, however, that confidence intervals for AUC overlap considerably between these short forms so that care must be taken when assessing best performance.

The full 60-item BNT used in the UK-ADC permitted the exploration of comparison between multiple BNT short-form versions and revealed the pitfalls of switching measures during the course of a study, namely that data arising from such protocols must be handled with care and should not be assumed to be equivalent. Tasks involving discrimination between cognitively normal and demented individuals will be well suited for the adoption of a harmonized BNT score, e.g., simply scaling to the same maximum scores across studies. Other neuropsychological measures that have varied by cohort as well as within a cohort can be approached in a similar manner to discern the ability to develop measures that can be appropriately incorporated in meta-analytic frameworks.

This study has some limitations. A number of the participants, including those with MCI and dementia, had been exposed to the CERAD BNT-15 prior to their first administration of the 60-item BNT. It is possible that practice effects elevated the scores on the BNT with repeated longitudinal assessment [27, 32, 33]. All short-form scores were derived via the full version. This may not correspond to the actual score if only a short form was administered. Additionally, the level of education in this sample was high (average of 15.8 years). The BNT is affected by the educational level [34]; thus, our findings may be different in a less educated sample. Similarly, interstudy differences in other potential confounders (e.g., ethnicity) may limit generalizability. Finally, because the BNT is used in the clinical consensus process per NACC UDS protocol, there may be some conflation regarding the independent predictive ability for cognitive diagnosis.

In summary, these results have important implications for the ability to use a uniform measure for the BNT when examining risk factors and covariates for dysnomia across multiple cohorts. Aside from the CERAD BNT-15, the internal consistency and high correlation between the short forms and the full BNT allow the adoption of a uniform measure across disparate data sources without much loss of information. This can be achieved relatively easily, by, for example, assimilation to a common range across all BNT forms.

Acknowledgements

We are profoundly appreciative of the study participants who made this work possible as well as Drs. David Wekstein and William Markesbery (both deceased), J. Wesson Ashford and Gregory Cooper, and the UK-ADC staff. This research was partially supported by the National Institute on Aging: grants R01 AG038651, P30 AG028383, and K25 AG043546.

Appendix 1

Items Included in the Short Forms.

| Item | CERAD BNT-15 | Lansing15 | Mack15.1 | Mack15.2 | Mack15.3 | Mack15.4 | Odd30 | Even30 | Mack30.A | Mack30.B | Williams30 | Saxton30.A | Saxton30.B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bed | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 2 | Tree | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 3 | Pencil | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 4 | House | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 5 | Whistle | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 6 | Scissors | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 7 | Comb | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 8 | Flower | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 9 | Saw | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 10 | Toothbrush | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 11 | Helicopter | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 12 | Broom | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 13 | Octopus | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 14 | Mushroom | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 15 | Hanger | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 16 | Wheelchair | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 17 | Camel | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 18 | Mask | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 19 | Pretzel | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 20 | Bench | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 21 | Racquet | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 22 | Snail | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 23 | Volcano | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 24 | Seahorse | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 25 | Dart | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 26 | Canoe | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 27 | Globe | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 28 | Wreath | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 29 | Beaver | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 30 | Harmonica | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 31 | Rhinoceros | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 32 | Acorn | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 33 | Igloo | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 34 | Stilts | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 35 | Dominoes | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| 36 | Cactus | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 37 | Escalator | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 38 | Harp | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 39 | Hammock | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||

| 40 | Knocker | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 41 | Pelican | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 42 | Stethoscope | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 43 | Pyramid | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 44 | Muzzle | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 45 | Unicorn | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 46 | Funnel | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 47 | Accordion | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 48 | Noose | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 49 | Asparagus | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 50 | Compass | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 51 | Latch | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 52 | Tripod | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 53 | Scroll | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 54 | Tongs | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 55 | Sphinx | X | X | X | X | X | ||||||||

| 56 | Yoke | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 57 | Trellis | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 58 | Palette | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||

| 59 | Protractor | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| 60 | Abacus | X | X | X | X | X |

Appendix 2

Summary of BNT Short-Form Scores for Each Type of Diagnosis.

| Version | All | Diagnosis |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| normal | MCI | dementia | |||

| CERAD BNT-15 | Mean ± SD | 14.3 ± 1.5 | 14.7 ± 0.7 | 14.2 ± 1.3 | 11.8 ± 2.8 |

| 95% CI | 14.2–14.4 | 14.6–14.7 | 13.9–14.4 | 11.1–12.4 | |

| Median (range) | 0.15 (6–15) | 0.15 (11–15) | 0.15 (10–15) | 0.12 (6–15) | |

| Lansing15 | Mean ± SD | 13.3 ± 2.7 | 14.2 ± 1.4 | 12.6 ± 2.6 | 8.6 ± 4.4 |

| 95% CI | 13.1–13.5 | 14.0–14.3 | 12.1–13.1 | 7.6–9.7 | |

| Median (range) | 0.14 (0–15) | 0.15 (6–15) | 0.13 (4–15) | 0.09 (0–15) | |

| Mack15.1 | Mean ± SD | 13.7 ± 2.2 | 14.3 ± 1.1 | 13.2 ± 2.0 | 9.6 ± 3.8 |

| 95% CI | 13.5–13.8 | 14.2–14.4 | 12.8–13.6 | 8.7–10.5 | |

| Median (range) | 15 (2–15) | 15 (9–15) | 14 (8–15) | 10 (2–15) | |

| Mack15.2 | Mean ± SD | 13.4 ± 2.1 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 12.9 ± 2.0 | 9.8 ± 3.3 |

| 95% CI | 13.2–13.5 | 13.8–14.1 | 12.5–13.3 | 9.0–10.6 | |

| Median (range) | 14 (3–15) | 14 (9–15) | 13 (7–15) | 10.5 (3–15) | |

| Mack15.3 | Mean ± SD | 13.4 ± 2.2 | 13.9 ± 1.2 | 13.1 ± 2.0 | 9.7 ± 3.5 |

| 95% CI | 13.2–13.6 | 13.9–14.1 | 12.7–13.5 | 8.8–10.5 | |

| Median (range) | 14 (3–15) | 14 (9–15) | 14 (6–15) | 10 (3–15) | |

| Mack15.4 | Mean ± SD | 13.3 ± 2.5 | 14.1 ± 1.5 | 12.3 ± 2.6 | 9.0 ± 3.5 |

| 95% CI | 13.1–13.5 | 13.9–14.2 | 11.8–12.8 | 8.1–9.8 | |

| Median (range) | 14 (3–15) | 15 (7–15) | 13 (6–15) | 9 (3–15) | |

| Odd30 | Mean ± SD | 26.7 ± 4.6 | 28.1 ± 2.3 | 25.3 ± 4.5 | 18.6 ± 7.1 |

| 95% CI | 26.4–27.0 | 27.9–28.3 | 24.4–26.2 | 16.9–20.3 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (6–30) | 29 (18–30) | 27 (12–30) | 19 (6–30) | |

| Even30 | Mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 4.1 | 28.2 ± 2.1 | 26.2 ± 3.6 | 19.5 ± 6.7 |

| 95% CI | 26.7–27.3 | 28.0–28.4 | 25.5–26.9 | 17.9–21.1 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (5–30) | 29 (18–30) | 27 (17–30) | 20 (5–29) | |

| Mack30.A | Mean ± SD | 27.0 ± 4.1 | 28.3 ± 2.1 | 26.1 ± 3.7 | 19.4 ± 6.8 |

| 95% CI | 26.6–27.3 | 28.1–28.4 | 25.4–26.8 | 17.8–21.0 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (5–30) | 29 (19–30) | 27 (16–30) | 5 (5–29) | |

| Mack30.B | Mean ± SD | 26.7 ± 4.5 | 28.1 ± 2.4 | 25.4 ± 4.3 | 18.6 ± 6.9 |

| 95% CI | 26.3–27.0 | 27.8–28.3 | 24.6–26.2 | 17.0–20.3 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (6–30) | 29 (18–30) | 27 (14–30) | 19.5 (6–30) | |

| Williams30 | Mean ± SD | 25.8 ± 5.6 | 27.5 ± 2.9 | 24.4 ± 5.3 | 15.5 ± 8.8 |

| 95% CI | 25.4–26.2 | 27.2–27.7 | 23.4–25.4 | 13.4–17.4 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (0–30) | 28 (15–30) | 25 (9–30) | 17.5 (0–30) | |

| Saxton30.A | Mean ± SD | 27.1 ± 4.1 | 28.3 ± 2.1 | 25.9 ± 3.9 | 19.8 ± 6.5 |

| 95% CI | 26.8–27.4 | 28.1–28.5 | 25.1–26.7 | 18.3–21.4 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (6–30) | 29 (18–30) | 27 (16–30) | 20 (6–30) | |

| Saxton30.B | Mean ± SD | 26.6 ± 4.6 | 28.0 ± 2.3 | 25.6 ± 4.2 | 18.2 ± 7.2 |

| 95% CI | 26.3–26.9 | 27.8–28.2 | 24.8–26.4 | 16.5–19.9 | |

| Median (range) | 28 (5–30) | 29 (19–30) | 27 (14–30) | 19.5 (5–30) | |

| 60-item BNT | Mean ± SD | 53.7 ± 8.5 | 56.3 ± 4.1 | 51.5 ± 7.8 | 38.0 ± 13.5 |

| 95% CI | 53.1–54.3 | 55.9–56.7 | 50.0–53.0 | 34.8–41.3 | |

| Median (range) | 57 (11–60) | 58 (38–60) | 54 (30–60) | 40 (11–59) | |

References

- 1.Rohrer JD, et al. Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias. Brain. 2008;131:8–38. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobs DM, et al. Neuropsychological detection and characterization of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1995;45:957–962. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.5.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hodges JR, Salmon DP, Butters N. Semantic memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease: failure of access or degraded knowledge? Neuropsychologia. 1992;30:301–314. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(92)90104-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaplan E, et al. Boston Naming Test. Lea & Febiger; Philadelphia: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmitt FA, et al. A brief instrument to assess treatment response in the patient with advanced Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:377–383. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181ac9cc1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/wnl.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fillenbaum G, Woodbury M. Typology of Alzheimer’s disease: findings from CERAD data. Aging Ment Health. 1998;2:105–127. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sotaniemi M, et al. CERAD -- neuropsychological battery in screening mild Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012;125:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lansing AE, et al. An empirically derived short form of the Boston naming test. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1999;14:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack WJ, et al. Boston Naming Test: shortened versions for use in Alzheimer’s disease. J Gerontol. 1992;47:P154–P158. doi: 10.1093/geronj/47.3.p154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams BW, Mack W, Henderson VW. Boston Naming Test in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 1989;27:1073–1079. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90186-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxton J, et al. Normative data on the Boston Naming Test and two equivalent 30-item short forms. Clin Neuropsychol. 2000;14:526–534. doi: 10.1076/clin.14.4.526.7204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graves RE, et al. Boston naming test short forms: a comparison of previous forms with new item response theory based forms. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:891–902. doi: 10.1080/13803390490510716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weintraub S, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Centers’ Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318191c7dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gollan TH, et al. Self-ratings of spoken language dominance: a Multilingual Naming Test (MINT) and preliminary norms for young and aging Spanish-English bilinguals. Biling (Camb Engl) 2012;15:594–615. doi: 10.1017/S1366728911000332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitt FA, et al. University of Kentucky Sanders-Brown healthy brain aging volunteers: donor characteristics, procedures and neuropathology. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:724–733. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riley KP, Snowdon DA, Markesbery WR. Alzheimer’s neurofibrillary pathology and the spectrum of cognitive function: findings from the Nun Study. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:567–577. doi: 10.1002/ana.10161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennett DA, et al. Overview and findings from the religious orders study. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2012;9:628–645. doi: 10.2174/156720512801322573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katz MJ, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific prevalence and incidence of mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer dementia in blacks and whites: a report from the Einstein Aging Study. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:335–343. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31823dbcfc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howieson DB, et al. Neurologic function in the optimally healthy oldest old. Neuropsychological evaluation. Neurology. 1993;43:1882–1886. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.10.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsai R, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: results from the Kerala Einstein Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:1369–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04012.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nelson PT, et al. Modeling the association between 43 different clinical and pathological variables and the severity of cognitive impairment in a large autopsy cohort of elderly persons. Brain Pathol. 2010;20:66–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beekly DL, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the Uniform Data Set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21:249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fastenau PS, Denburg NL, Mauer BA. Parallel short forms for the Boston Naming Test: psychometric properties and norms for older adults. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1998;20:828–834. doi: 10.1076/jcen.20.6.828.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terwee CB, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.R Development Core Team . A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathews M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy and practice effects in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center Uniform Data Set neuropsychological battery. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10:675–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petersen RC, et al. Mild cognitive impairment: a concept in evolution. J Intern Med. 2014;275:214–228. doi: 10.1111/joim.12190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jicha GA, et al. Clinical features of mild cognitive impairment differ in the research and tertiary clinic settings. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2008;26:187–192. doi: 10.1159/000151635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rountree SD, et al. Importance of subtle amnestic and nonamnestic deficits in mild cognitive impairment: prognosis and conversion to dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;24:476–482. doi: 10.1159/000110800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teng E, et al. Persistence of neuropsychological testing deficits in mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28:168–178. doi: 10.1159/000235732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathews M, et al. CERAD practice effects and attrition bias in a dementia prevention trial. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013;25:1115–1123. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burkhart CS, et al. Evaluation of a summary score of cognitive performance for use in trials in perioperative and critical care. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31:451–459. doi: 10.1159/000329442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Welch LW, et al. Educational and gender normative data for the Boston Naming Test in a group of older adults. Brain Lang. 1996;53:260–266. doi: 10.1006/brln.1996.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]