Abstract

Freeze-quenching nitrogenase during turnover with N2 traps an S = ½ intermediate that was shown by ENDOR and EPR spectroscopy to contain N2 or a reduction product bound to the active-site molybdenum-iron cofactor (FeMo-co). To identify this intermediate (termed here EG), we turned to a quench-cryoannealing relaxation protocol. The trapped state is allowed to relax to the resting E0 state in frozen medium at a temperature below the melting temperature; relaxation is monitored by periodically cooling the sample to cryogenic temperature for EPR analysis. During −50°C cryoannealing of EG prepared under turnover conditions in which the concentrations of N2 and H2 ([H2], [N2]) are systematically and independently varied, the rate of decay of EG is accelerated by increasing [H2] and slowed by increasing [N2] in the frozen reaction mixture; correspondingly, the accumulation of EG is greater with low [H2] and/or high [N2]. The influence of these diatomics identifies EG as the key catalytic intermediate formed by reductive elimination (re) of H2 with concomitant N2 binding, a state in which FeMo-co binds the components of diazene (an N-N moiety, perhaps N2 and two [e−/H+] or diazene itself). This identification combines with an earlier study to demonstrate that nitrogenase is activated for N2 binding and reduction through the thermodynamically and kinetically reversible reductive-elimination/oxidative-addition exchange of N2 and H2, with an implied limiting stoichiometry of eight electrons/protons for the reduction of N2 to two NH3.

Introduction

Biological nitrogen fixation — the reduction of N2 to two NH3 molecules — is primarily catalyzed by the Mo-dependent nitrogenase. This enzyme comprises an electron-delivery Fe protein and MoFe protein, a dimer of dimers that contains two copies of the active site FeMo-cofactor (FeMo-co).1,2 A suggested limiting stoichiometry for nitrogen fixation,3

| (1) |

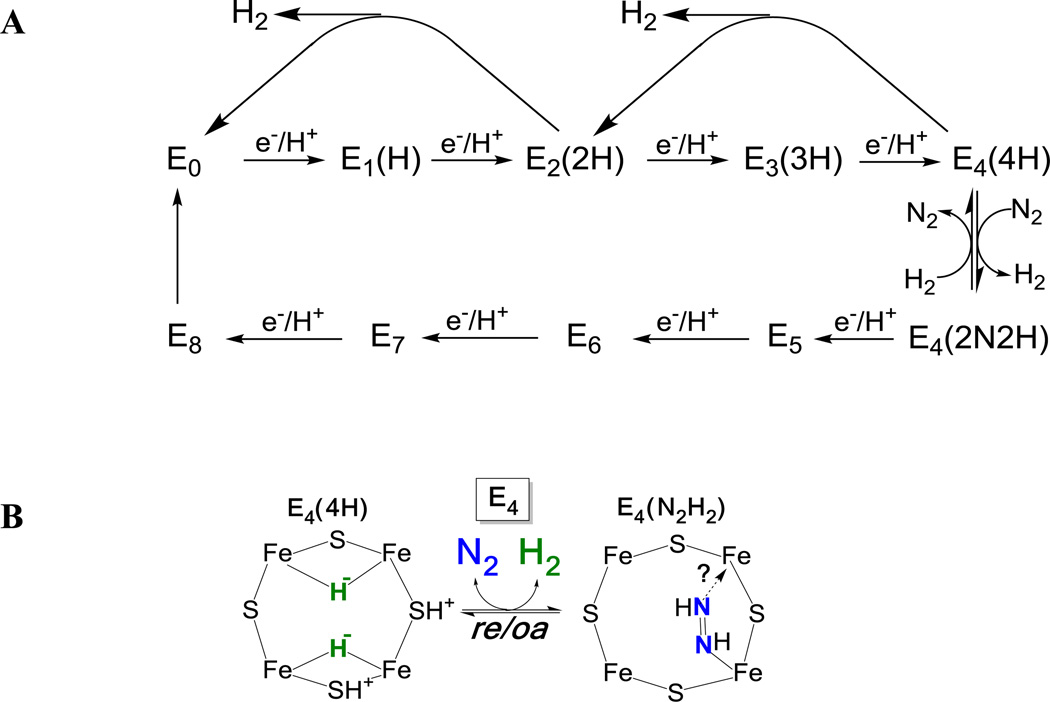

incorporates an obligatory formation of one mole of H2 per mole of N2 reduced, and thus a puzzling requirement for two reducing equivalents and four ATP beyond the chemical requirement for N2 reduction.1,2 This stoichiometry is embodied in a kinetic framework for nitrogenase function provided by the Lowe-Thorneley (LT) model,1,2,4 which describes transformations among catalytic intermediates (denoted En) where n is the number of electrons and protons (n = 0 – 8) delivered to one half of the MoFe protein (Figure 1A). In this model, N2 reduction requires activation of the MoFe protein to the pivotal E4(4H) state (see the kinetic scheme of Figure 1, where the legend explains notation), in which ENDOR has shown FeMo-co to have accumulated four reducing equivalents stored in the form of two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides,5–7 presumably with two protons bound to sulfides of FeMo-co (Figure 1B, left).5,7–9 We recently proposed8, 10 and subsequently provided experimental evidence11 that nitrogenase is activated for N2 binding and reduction through reductive elimination (re)12–15 of the two bridging hydrides of E4(4H) to form H2 (Figure 1B), thereby experimentally supporting the stoichiometry of eq 1.

Figure 1.

(A) Simplified LT kinetic scheme highlighting correlated electron/proton delivery in eight steps, with inclusion of some of the possible pathways for decay by H2 release; although N2 binds at either the E3 or E4 levels, only the E4 state is reactive, so the pathway through the E4 state is emphasized. For states under discussion in this report, parentheses added to the En notation to denote the stoichiometry of H/N bound to FeMo-co. When the molecular species corresponding to this stoichiometry is specified, it is noted; for example, E4(2N2H) might have N2 or N2H2 bound, and would be notated as E4(N2,2H) and E4(N2H2). (B) The reductive-elimination (re) mechanism for H2 release upon N2 (blue) binding to E4(4H) and its reverse, oxidative-addition (oa) of H2 with loss of N2 (eq 4) visualized as occurring on the FE2,3,6,7 face of FeMo-co. The binding modes of the hydrides of E4(4H) and the components of diazene in E4(2N2H) are arbitrary.

As part of the development of the re mechanism we used advanced paramagnetic techniques to characterize two nitrogenous En intermediates that are associated with states in the LT scheme subsequent to N2 binding, n ≥ 4 (Figure 1), and that are common to turnover of remodeled nitrogenase with N2H2, Me-N2H, N2H4, NO2−, and H2NOH. One is a non-Kramers (S ≥ 2) state, denoted H, that is assigned as E7, with bound [-NH2]; the second is a Kramers (S = ½) state, denoted I, assigned as E8, with bound NH3.8, 10,16 During turnover of wild-type nitrogenase with N2 an additional intermediate state with S = ½ was trapped, but not identified.17–19 With a half-integer spin, like the E0 resting state, this state must differs from E0 by the accumulation of the delivery of an n = even number of [e−/H+] to FeMo-co, This state, herein denoted as EG, must further correspond to an En state formed subsequent to binding N2, n = 4, 6, or 8, because it gives 15N ENDOR signals when trapped using 15N2 substrate. The previous assignment of I as E8, a product (NH3)-bound state,8, 10 implies an assignment of EG to E4 or E6. The notation, EG, in fact was adopted because if the states of Figure 1A were to be labeled sequentially by letters beginning with E0 = A, then E4 would be E and E6 would be G.

Because of the relatively low accumulation of EG in freeze-quenched samples, to date neither ENDOR measurements nor the use HYSCORE, as successfully applied to intermediate I,20 have yielded an assignment of EG. To identify EG, we therefore here turn to a quench-cryoannealing relaxation protocol developed to determine the reduction level, n, of an EPR-active freeze-trapped En intermediate state.6 The trapped state is allowed to relax to the resting E0 state in frozen medium, at temperatures T ≤ −20°C, well below the melting temperature of the buffered samples, T ~ 0°C. Keeping the sample frozen prevents any additional accumulation of reducing equivalents, because binding of reduced Fe protein to and release of oxidized protein from the MoFe protein both are abolished in a frozen solid. As recently confirmed,21 the frozen intermediate can relax towards the resting state only through steps that release a stable species from FeMo-co. The En states formed prior to N2 binding lose two equivalents per relaxation step by releasing H2: E2(2H) relaxes to E0 with loss of H2; E3(3H) can relax to E1(1H) by loss of H2, but as there is no center available to accept a single electron, E1(1H) cannot further relax to E0;21 E4 is a special case with multiple substates (Figure 1B), which will be discussed. States formed subsequent to N2 binding/reaction, n ≥ 4, would relax through release of a stable form of reduced substrate. As the defining example of this approach, the freeze-trapped S = ½ intermediate shown by ENDOR spectroscopy to exhibit two [Fe-H-Fe] bridging hydrides5,7 was identified as E4(4H) by its relaxation to the resting state E0 through the release of a total of four reducing equivalents in a two-step process, each step releasing H2 (two equivalents), with formation of E2(2H) in the first step (Figure 1A).6

Application of this quench-cryoannealing relaxation protocol to EG identifies its En turnover state as one in which the N-N bond is intact. Most importantly, the results combine with our earlier study11 to directly demonstrate that nitrogenase activation occurs as a thermodynamically and kinetically reductive-elimination/oxidative-addition exchange of N2 and H2 at the E4 reduction level, as represented by Figure 1B.

Materials and Methods

General procedures

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals, and were used without further purification. Hydrogen, argon, and dinitrogen gases were purchased from Air Liquide America Specialty Gases LLC (Plumsteadville, PA). The argon and dinitrogen gases were passed through an activated copper-catalyst to get rid of contamination of oxygen before use. Azotobacter vinelandii strains DJ995 (wild type MoFe protein) and DJ884 (wild type Fe protein) were grown and nitrogenase proteins were expressed and purified as previously described.22 Both proteins were greater than 95% pure as confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis using Coomassie blue staining, and were fully active, as discussed in SI. Proteins and buffers were handled anaerobically in septum-sealed serum vials under an inert atmosphere (argon or dinitrogen) or on a Schlenk vacuum line. All transfers of gases and liquids were done with Hamilton gastight syringes.

Preparation of Cryoannealing samples

Samples were prepared by adding Fe protein and MoFe protein to a solution containing a MgATP regeneration system, such that the final concentrations were 13 mM ATP, 15mM MgCl2, 20 mM phosphocreatine, 2.0 mg/mL bovine serum albumin, and 0.3 mg/mL phosphocreatine kinase (200 mM MOPS buffer at pH 7.3 with 50mM dithionite). MoFe protein was added first to a final concentration of ~50 µM; reaction was then initiated by the addition of Fe protein to a final concentration of ~75 µM. After 20–25 sec incubation at room temperature, ~300 µL of the reaction mixture (total volume ~ 400 µL) was transferred into 4-mm calibrated quartz EPR tubes and rapidly frozen in a hexane slurry before being stored in liquid nitrogen for EPR analysis. When effects of ammonium ion were studied, reaction mixtures contained a final ammonium chloride concentration of 0.2 mM.

To prepare unstirred samples with a selected N2 partial pressure under normal conditions, N2 (or Ar) gas was added to an argon (or N2)-filled 9.4-mL assay vial with a 500 µL Eppendorf tube inside. The final pressure in all vials was 1 atm. When the stirring effect was studied, the assay vial contained a small magnetic stirring bar, the final volume of liquid phase was doubled to 0.8 mL, and the reaction mixture was stirred to equilibrate the gas and liquid phases. To study the effect of gas flushing in addition to stirring, the gas mixture with the chosen N2 partial pressure in a 60-mL syringe was flushed through the headspace of the reaction vial from a syringe inserted through the water-sealed septum and ventilated through a second water-sealed small syringe attached through the septum; a total volume of 30 mL of gas mixture was flushed through the reaction vial prior to freezing. The NH3, H2 and N2 concentrations in frozen samples prepared with the two protocols, unstirred and stirred, were estimated as described in SI (Figures S1–S3).

Cryoannealing EPR methods

The cryoannealing protocol has been described.6, 21 It involves multiple steps in which a freeze-quenched sample at liquid nitrogen temperature is rapidly warmed to the annealing temperature by immersion in a methanol bath held at that temperature, annealed at that temperature for a fixed time, then quench-cooled back to 77 K by immersion into liquid nitrogen. CW X-band EPR is then collected on an ESP 300 Bruker spectrometer equipped with Oxford ESR 900 cryostat.

A freeze-trapped intermediate, En, typically decays with a distribution of rate constants, which can be described with a stretched exponential function, eq 2,23

| (2) |

where τ is the average decay time and 0 ≤ m ≤ 1 reflects the breadth of the distribution, with m decreasing as the breadth of the distribution increases.24 In formulating the differential equations of a multi-step process, the distribution of rate constants that characterizes a stretched exponential decay is manifest as a time-dependent rate constant, k(t).6, 24

Results and Discussion

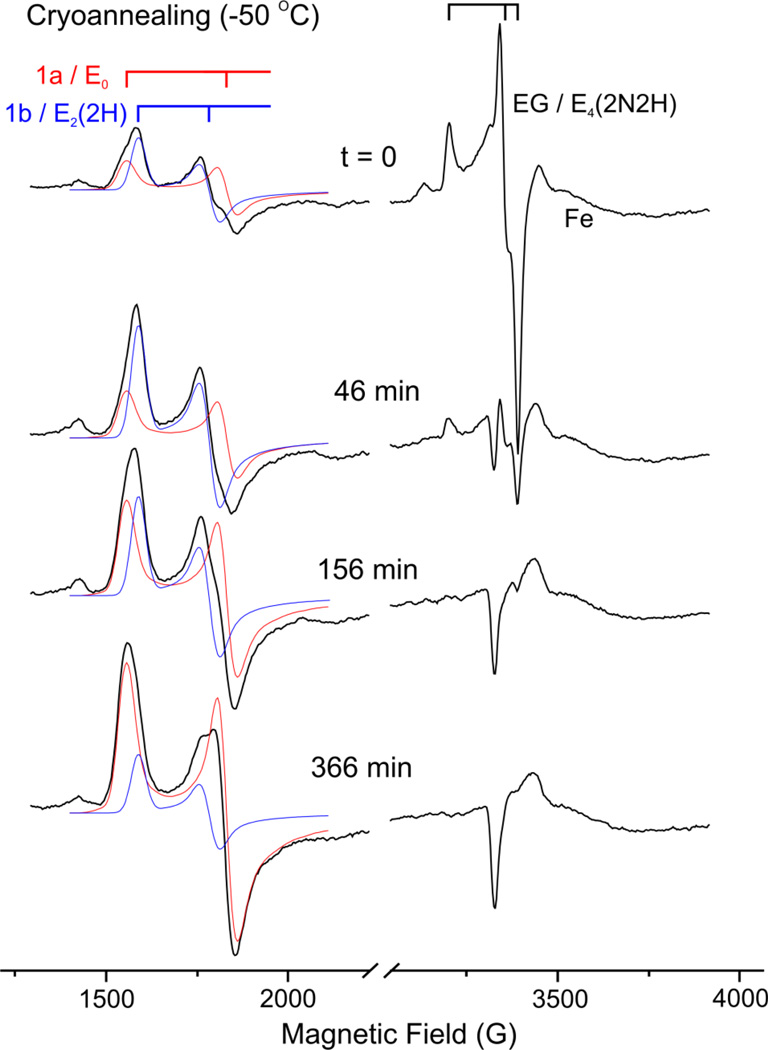

Figure 2 (t = 0) presents the EPR spectrum of nitrogenase quench-frozen during steady-state turnover (ca. 25 sec after mixing) under an N2 partial pressure (P(N2)) of 0.05 atm. At low fields it shows the g1/g2 features of S = 3/2 signals, and is decomposed as previously described21 (also see legend to Figure 3) into a contribution from the E0 resting-state FeMo-co (signal denoted 1a), and a larger contribution from the E2(2H) intermediate (denoted 1b).6, 21 The g-2 region is dominated by the spectrum for the S = ½ EG intermediate, g = [2.08, 1.99, 1.97].

Figure 2.

Selected EPR spectra collected during the time course for −50°C cryoannealing of a sample freeze-trapped under P(N2) = 0.05 atm, and showing the decompositions of the S = 3/2 spectra in the low-field g1g2 region into contributions from 1a (g = [4.32, 3.66, 2.01], red) and 1b (g = [4.21, 3.76, ~1.97], blue). At early time the g-2 region is dominated by EG, as indicated. The indicated signal from the reduced 4Fe/4S cluster of Fe protein is greatly distorted at this temperature, but it is clear that its intensity does not change with annealing. EPR conditions: temperature, 3.8 K; microwave frequency, 9.36 GHz; microwave power, 0.5 mW; modulation amplitude, 13 G; time constant, 160 ms; field sweep speed, 38 G/s.

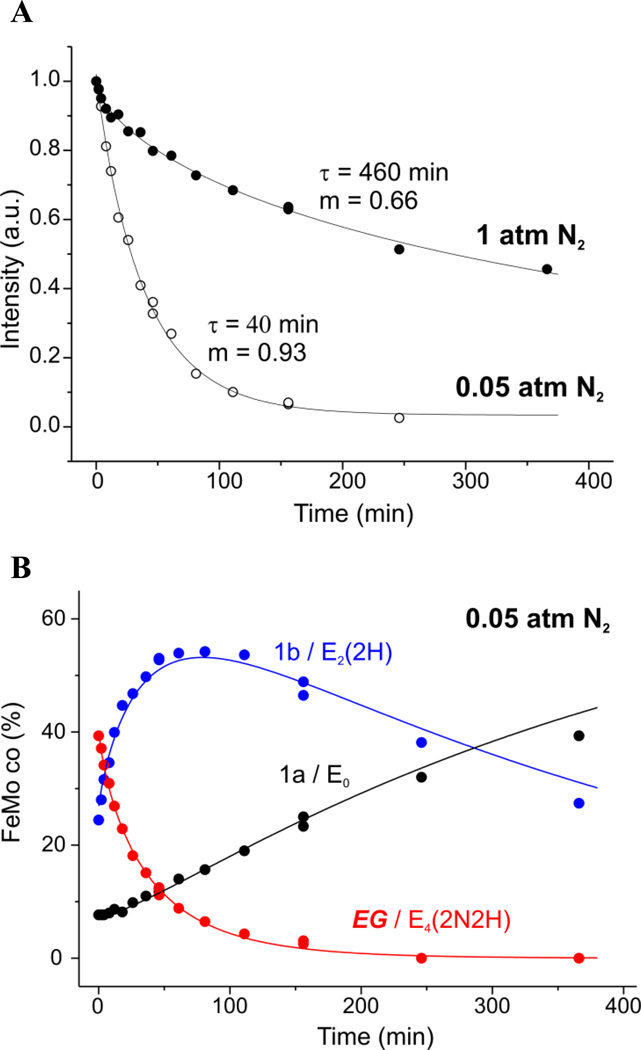

Figure 3.

(A) Decay of intermediate EG freeze-trapped during turnover of nitrogenase under P(N2) = 0.05 (open circles; see Figure 2) and 1 atm (solid circles) observed during cryoannealing at −50 °C. Plotted are intensities of g1 feature of the S = ½ EPR signal, shown after normalization to the maximum (zero-time) signal and fitted with a stretched exponential decay function, eq 2. EPR conditions: as for Figure 2, except for field sweep speed of 20 G/s. (B) Progress curves for the three EPR-active species, EG, 1a, and 1b, observed during cryoannealing of EG freeze-trapped under P(N2) = 0.05 atm. Fits to kinetic scheme (eq 3) as previously described; parameters of k1 for EG stretched-exponential decay presented in 3A; rate of the second step of eq 3, k2 = 0.0023 min−1.6, 21 Intensities for the resting state (black) and E2 state (blue) obtained with the previously described21 procedure of deconvolution and quantitation of corresponding S = 3/2 EPR signals 1a and 1b (see Figure 2). Intensities for the EG intermediate (red) taken from Figure 3A and converted to concentration units by scaling to the two-step kinetic scheme for decay, eq 3. EPR conditions: as for Figure 3A, except for field sweep speed of 38 G/s for 1a and 1b signals detection.

Figure 2 further shows representative spectra collected during −50 °C cryoannealing of the freeze-trapped sample; the EG decay at higher annealing temperatures, (e.g., −20 °C) was too rapid to monitor conveniently. As shown, the annealing leads to progressive loss of the EG signal and increase in the E0 signal, plus a rise then fall of the E2 signal.

Figure 3A presents the progress curves for −50 °C cryoannealing of samples trapped during steady-state turnover both under (P(N2)) of 0.05 and 1 atm. As is commonly the case in cryoannealing,6, 23 the decay of EG formed under a partial pressure of P(N2) = 1 atm is best described with a stretched exponential,24 eq 2, indicating that there is a distribution of rate constants associated with an ensemble of slightly differing conformations of the intermediate trapped in the frozen solution. The decay at this temperature is slow, with an average decay time of τ = 460 min and a ‘stretch’ constant, m = 0.66. Strikingly, when EG is trapped during turnover under an atmosphere of only P(N2) = 0.05 atm, the decay dramatically speeds up: the average decay time decreases more than twelve-fold, to τ = 40 min; moreover, the decay becomes nearly exponential, m = 0.93.

As shown in Figure 2 and illustrated in 3B, decay of EG during cryoannealing leads to the appearance of the S = 3/2 signal, denoted 1b, associated with the E2(2H) intermediate.6, 21 This species in turn decays with the gradual recovery of resting state E0. As ENDOR measurements show that EG is a state that has bound N2,8, 10,16 and this state decays through E2(2H) to E0 during cryoannealing, then according to Figure 1A EG can only be E4(2N2H). According to this kinetic model, E4(2N2H) relaxes via E4(4H) and E2(2H) to resting state E0 with loss of N2 and two H2. This is described by Scheme 1, which extracts from Figure 1A those states associated with relaxation of E4(2N2H) to resting E0. Multiple repetitions of the experiment, have shown that in general low amounts of an intermediate whose EPR signal can be assigned to E4(4H) are freeze-trapped, and that little-to-no additional E4(4H) accumulates during annealing. As a result of the latter, in particular, the curves for all three observed species can be described jointly6 by the phenomenological two-step sequential kinetic scheme derived from Scheme 1 under the condition of minimal accumulation of E4(4H), eq 3;

| (3) |

This implies a steady-state approximation for the concentration of E4(2N2H), presented below; the relationship between the observed EG/E4(2N2H) decay constants, k1, k2, of eq 3, and the microscopic rate constants of Scheme 1 are derived there.

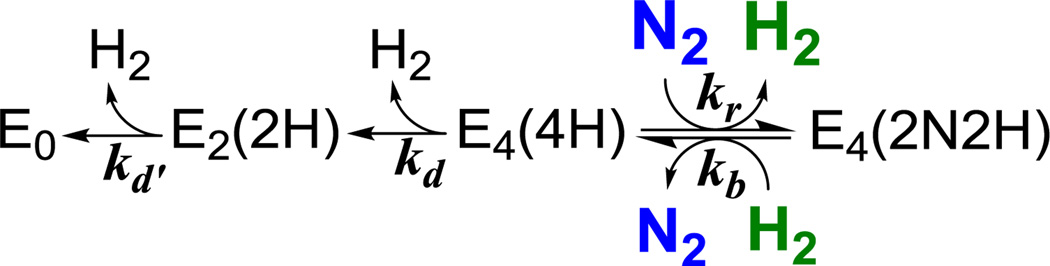

Scheme 1.

Kinetic scheme for the decay of freeze-trapped E4(2N2H) derived from Figure 1A; kr and kb are the second-order rate constants for re and its reverse; kd and kd’ are the rate constants for the irreversible10 decay of E4(4H) and E2(2H), respectively.

The progress curves for the three species, EG/E4(2N2H), 1b/E2(2H), and 1a/E0, are indeed well-fit by the kinetic relaxation scheme of eq 3, as illustrated for the sample trapped under P(N2) = 0.05 atm (Figure 3B). In agreement with this scheme, the appearance of 1b/E2(2H) follows the stretched-exponential (eq 2) associated with the decay of EG, with changes in the partial pressure P(N2) causing the sharp changes in the average decay time and stretch factor that characterize k1, as presented above. Correspondingly, 1a/E0 appears with the rate constant associated with relaxation of 1b/E2(2H). In contrast, one expects the relaxation of E2(2H) to E0 to be independent of turnover conditions,6, 21 and this is so. At both values of P(N2), the process can be described by an exponential with the same rate constant, implying that k2 = kd’ of Scheme 1.

The assignment of EG as E4(2N2H) has been tested, and confirmed, by experiments inspired by the question, why does increasing the concentration of the substrate [N2] in the frozen solution slow the decay of E4(2N2H) (Figure 3A), which led to the further questions, what are the possible influence(s) on EG decay of the turnover products, NH3 and H2? We first tested whether the NH3 product (NH4+ at pH 7.3) is the causative agent, perhaps because it binds to MoFe in the vicinity of the FeMo-co of E4(2N2H) and stabilizes the intermediate, for example by H-bonding to a partially reduced N2. As NH3 production increases with increasing P(N2) (Figure S1), such an effect would be enhanced at high P(N2), thereby decreasing the rate of decay, as observed.

To test this hypothesis, we first quantified the ammonia concentration in the samples prepared under the freeze-quench turnover conditions used for making the EPR samples in Figure 3. The total concentration of ammonia (NH4+ at pH 7.3) generated under 1 atm of N2 is about 0.15 mM; that produced under 0.05 atm of N2 is about four to five fold less (Figure S1). We then freeze trapped B during turnover under 0.05 atm of N2 in the presence of 0.2 mM of externally added NH4+, even more than the amount produced at 1 atm of N2. There is no previous report of which we are aware that suggested the presence of NH4+ alters catalysis, and we find that added NH4+ has no influence on either the intensity of the EPR signal from trapped EG or the cryoannealing kinetics of EG (not shown). Hence we discard this possibility.

An influence of the diatomics N2 and H2 on E4(2N2H) decay is implicit in our mechanistic proposal that E4(2N2H) is formed by N2 binding and H2 release through re, Figure 1B. According to this mechanism, decay of EG would occur by the reverse of the re equilibrium, (Scheme 1) and would involve reaction with the H2 formed during turnover with release of N2 to generate E4(4H). Hence, decay would be enhanced by increasing [H2]; the E4(4H) thus formed by reaction with H2 would in turn decay to E0 through the successive release of two H2. However, the E4(4H) can re-react with N2 in the frozen solution to regenerate E4(2N2H), so increasing [N2] would suppress the decay. Thus, according to this reversible-re scenario, varying the concentrations [H2] and [N2] in frozen samples would competitively modulate both the accumulation and annealing of EG.

According to this hypothesis, decay of E4(2N2H) is slower in samples prepared under high P(N2), Figure 3, because the E4(4H) state formed during E4(2N2H) decay undergoes enhanced regeneration back to E4(2N2H) through reaction with the high solution concentration of N2 according to Scheme 1. Indeed, the measurements of [N2] in solution, Figure S3, show that [N2] in the solution prepared at P(N2) = 1 atm is more than an order of magnitude higher than that at 0.05 atm. This in turn correlates with the more than ten-fold slower decay of EG in the sample prepared under high P(N2), consistent with the expectation E4(2N2H) decay is being suppressed by enhanced re-reaction of E4(4H) with dissolved N2 to regenerate E4(2N2H). One might imagine that the difference in decay rates of Figure 3 reflects the reaction of E4(2N2H) with differing concentrations of H2 formed during turnover under the different values of P(N2). However, experiments described in SI argue against this alternative. Although more H2 is produced during turnover under low P(N2),1,2,3 saturating concentrations of H2 are produced by the enzymatic reaction under all partial pressures of N2 used (Figure S2).

To test the reversible-re hypothesis in experiments where both [H2] and [N2] are actively varied, we complemented our standard procedures for sample preparation with the simple expedient of flushing the headspace with an N2/Ar mixture of selected P(N2) while rapidly stirring, thereby sweeping out the enzymatically produced H2 into the headspace over the reaction mixture and generating samples with low [H2], while ensuring equilibration of the reaction mixture with the selected P(N2) in the headspace gas phase. Stirred and unstirred sample pairs prepared with the same P(N2) have essentially the same [N2], but the unstirred samples have high (saturating) [H2], while the stirred samples have low [H2].

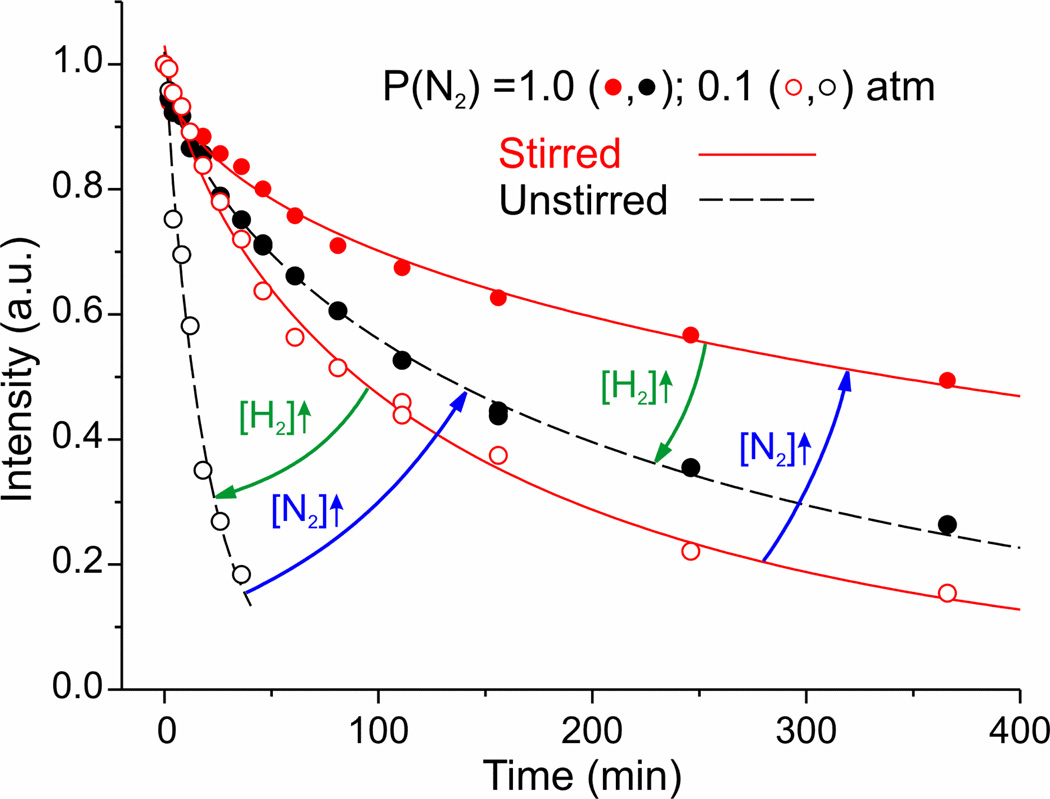

Figure 4 presents the results of −50°C cryoannealing of two stirred/unstirred pairs of samples of intermediate EG freeze-trapped during steady-state turnover. One pair was under P(N2) = 0.1 atm and 0.9 atm of Ar; the second pair was freeze-trapped under P(N2) = 1 atm. Comparison of decay curves for sample pairs with high vs low P(N2), both the stirred and the unstirred pairs, again shows that high [N2] suppresses E4(2N2H) decay, regardless of whether the solution contains high [H2] (unstirred) or low (stirred).25 Conversely, the effects of stirring on samples prepared under equal P(N2) show that the higher [H2] in the unstirred partner of a pair with identical P(N2) speeds the decay, regardless of whether [N2] is high (P(N2) = 1 atm) or low (0.1 atm).

Figure 4.

| Turnover conditions |

P(N2) = 0.1 atm | P(N2) = 1 atm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unstirred | Stirred | Unstirred | Stirred | |

| τ (min) | 19 | 142 | 224 | 667 |

| m | 0.94 | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.55 |

Examination of Figure 1 shows that these effects clearly identify EG as E4(2N2H). Considering the other En, n ≥ 4, even, states, as noted above, E8 has already been identified with intermediate I, and in any case would not respond to changes in [N2] or [H2]. Whether E6, which we have assigned as binding N2H4,8, 10 decayed by loss of N2H4 or through the release of N2H2 and H2, it would not respond to changes in [N2], and increasing [H2] would not speed its decay. Moreover, even in an alternative reaction pathway that has been discussed,8, 10 where E6 contains a moiety generated by cleavage of the N-N bond, here too its decay could not be influenced by changes in [N2] or [H2]. Instead, Figure 1 shows that the effects of the two diatomics clearly require not only that EG is E4(2N2H), but also that its decay, Figs 3, 4, is to be understood as the reverse of the re activation equilibrium,

| (4) |

which leads to the decay of E4(2N2H) through Scheme 1: the oxidative-addition reaction of E4(2N2H) with H2 and loss of N2 to form E4(4H) (kb). The competing regeneration of E4(2N2H) from E4(4H) through reaction with N2 (kr) and reductive elimination of H2, in turn competes with the irreversible relaxation of E4(4H) through loss of H2 (kd). This competition is captured by a steady-state treatment of the concentration of E4(4H) within the kinetic relaxation Scheme 1, which generates as the functional form for k1(t), the observed rate constant of E4(2N2H) relaxation according to eq 3,26

| (5a) |

In the limit of eq 5a where kd << kr[N2], the two states E4(2N2H) and E4(4H) are in an equilibrium controlled by the ratio, [H2]/[N2]; the equilibrium population decays to E2(2H) with loss of H2, with rate constant k1(t) represented by the limiting form of eq 5b,

| (5b) |

in agreement with the behavior exhibited in the present experiments, Figure 4. The rate constant k1(t) is expected to be time-dependent because the distribution of rate constants that characterizes a stretched-exponential decay in the frozen solid23 is manifest as a time-dependent rate constant;24 time-dependence of the concentrations of the diatomics during annealing of the frozen solutions would also contribute. If conditions can be established such that E4(4H) is trapped in quantities that allow kd for wild-type nitrogenase to be measured directly, then the equilibrium constant of re (Figure 1B, eq 4), (kr/kb) in Scheme 1, can be estimated from eq 5b.

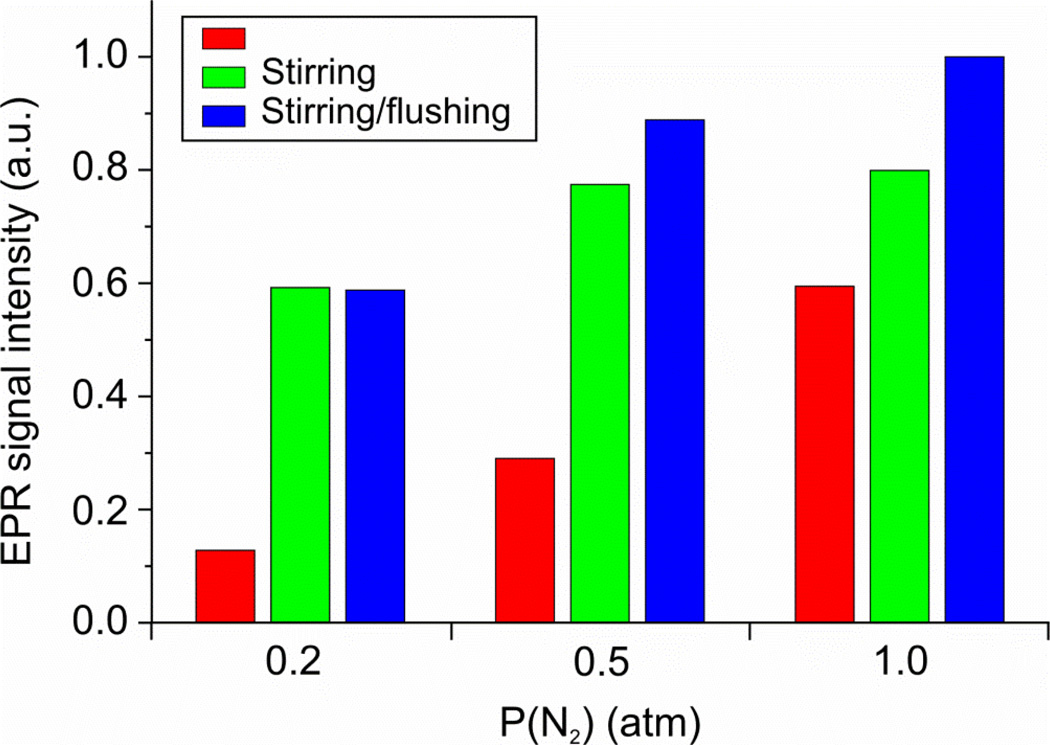

We also studied the effects of varying [H2] and [N2] on the amount of EG/E4(2N2H) trapped through the preparation of paired samples, with and without stirring/flushing, under a range of N2 partial pressures, Figure 5. At the low partial pressure of P(N2) = 0.2 atm, stirring/flushing to remove H2 increases the concentration of trapped EG by ~4–5 fold. However, as the partial pressure of N2 substrate rises, the significance of stirring/flushing drops, and by 1 atm N2 the increase is less than two-fold. The improved yield of EG by stirring/flushing effect can be easily explained by the effect of changes of [H2] and [N2] on the competition of H2 with N2 for binding to the different E4 substates, as shown in Figure 1B and eq 4. Under all partial pressures employed, a saturating level of H2 is generated in the unstirred sample (Figure S2), so the removal of H2 by stirring/flushing would have (roughly) the same influence for all samples. However, the majority of dissolved N2 is used up before freezing when P(N2) is low, but there is considerable residual N2 at the time of freezing for high P(N2) (Figure S3). Thus, the equilibration of the gaseous and solution N2 has a lesser effect at high P(N2).

Figure 5.

Variation in the EPR amplitude of trapped intermediate EG g1 feature at various N2 partial pressures when reaction mixture is neither stirred nor flushed (red); stirred (green); stirred with the headspace of reaction vial flushed with appropriate N2/Ar mixture during turnover. EPR conditions: as described in Figure 3A.

Conclusions

EPR/ENDOR spectroscopy has shown that the S = ½ intermediate EG freeze-trapped during turnover of nitrogenase under N2 contains N2 or a reduction product bound to FeMo-co.17,18,19 This implies that the intermediate must be an En state with n = 4, 6, or 8. Cryoannealing experiments on EG prepared under turnover conditions in which the concentrations, [H2], [N2] are systematically varied demonstrate that reaction of EG with the H2 produced during turnover enhances the decay of EG and limits its accumulation, whereas reaction of N2 with E4(4H) formed during the decay process slows the observed decay of EG. In the kinetic scheme of Figure 1A there is only one such state that could be affected by H2, namely E4(2N2H), the key catalytic intermediate formed upon reductive elimination of H2 and binding of N2 (Figure 1B), whose decay involves the [H2], [N2] diatomics through the process visualized in Scheme 1. EG/E4(2N2H) is a state in which FeMo-co binds the components of diazene, which may be present as N2 and two [e−/H+] or as diazene itself, an issue to be addressed by future ENDOR measurements. Overall, however, the freeze-quench strategy nonetheless has trapped three of the five intermediate states in which N2 is involved: one of the substates of E4, E7, E8,5,7–9 leaving only E5, E6 unexamined.

Of primary importance, the present finding that decay of EG is accelerated by increasing [H2] and slowed by increasing [N2] in the frozen reaction mixture, and the resulting identification of EG as E4(2N2H) directly demonstrates that activation of nitrogenase for N2 binding and reduction involves the thermodynamically and kinetically reversible reductive-elimination/oxidative-addition (re/oa) activation equilibrium of Figure 1B and eq 4, as previously inferred,11 with its implied limiting stoichiometry of eight electrons/protons for the reduction of N2 to two NH3 (eq 1).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by the NIH (GM 111097, BMH) and the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (LCS and DRD).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Details of activity assays and of the estimation of H2 and N2 concentration in frozen EPR samples (3 figures). This information is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Citations

- 1.Burgess BK, Lowe DJ. Chem. Rev. 1996;96:2983. doi: 10.1021/cr950055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorneley RNF, Lowe DJ. Metal Ions in Biology. 1985;7:221. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson FB, Burris RH. Science. 1984;224:1095. doi: 10.1126/science.6585956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson PE, Nyborg AC, Watt GD. Biophysical Chemistry. 2001;91:281. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Dos Santos PC, Lee HI, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6231. doi: 10.1021/ja043596p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lukoyanov D, Barney BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. PNAS. 2007;104:1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610975104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lukoyanov D, Yang Z-Y, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:2526. doi: 10.1021/ja910613m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman BM, Lukoyanov D, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013;46:587. doi: 10.1021/ar300267m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doan PE, Telser J, Barney BM, Igarashi RY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:17329. doi: 10.1021/ja205304t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman BM, Lukoyanov D, Yang ZY, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:4041. doi: 10.1021/cr400641x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Z-Y, Khadka N, Lukoyanov D, Hoffman Brian M, Dean Dennis R, Seefeldt Lance C. PNAS. 2013;110:16327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315852110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crabtree RH. The Organometallic Chemistry of the Transition Metals. 5th ed. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballmann J, Munha RF, Fryzuk MD. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:1013. doi: 10.1039/b922853e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubas GJ. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4152. doi: 10.1021/cr050197j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peruzzini M, Poli R, editors. Recent Advances in Hydride Chemistry. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaw S, Lukoyanov D, Danyal K, Dean DR, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12776. doi: 10.1021/ja507123d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM, Dean DR. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2009;78:701. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070907.103812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barney BM, Lukoyanov D, Igarashi RY, Laryukhin M, Yang T-C, Dean DR, Hoffman BM, Seefeldt LC. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9094. doi: 10.1021/bi901092z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barney BM, Yang T-C, Igarashi RY, Santos PCD, Laryukhin M, Lee H-I, Hoffman BM, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14960. doi: 10.1021/ja0539342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lukoyanov D, Dikanov SA, Yang ZY, Barney BM, Samoilova RI, Narasimhulu KV, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11655. doi: 10.1021/ja2036018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukoyanov D, Yang ZY, Duval S, Danyal K, Dean DR, Seefeldt LC, Hoffman BM. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:3688. doi: 10.1021/ic500013c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christiansen J, Goodwin PJ, Lanzilotta WN, Seefeldt LC, Dean DR. Biochemistry. 1998;37:12611. doi: 10.1021/bi981165b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davydov R, Hoffman BM. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2011;507:36. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Phillips JC. Reports on Progress in Physics. 1996;59:1133. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Although [N2] is somewhat depleted in the unstirred samples relative to that of the stirred samples, the effect is minimal in this context (SI).

- 26.For completeness, we might add to k1(t) a rate constant k0(t) that is independent of diatomic concentrations and represents the possibility of ‘simple’ loss of N2 and stepwise return to ground. However, the observed control of the decay by [H2]/[N2] shows that such a process, if operative at all, cannot be making a significant contribution.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.