Abstract

Purpose

To quantitatively map cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) and oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) in human brains using quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) and arterial spin labeling measured cerebral blood flow (CBF) before and after caffeine vasoconstriction.

Methods

Using the multiecho 3D gradient echo sequence and an oral bolus of 200 mg caffeine, whole brain CMRO2 and OEF were mapped at 3mm isotropic resolution on 13 healthy subjects. The QSM based CMRO2 was compared with an based CMRO2 to analyze the regional consistency within cortical gray matter (CGM) with the scaling in the method set to provide same total CMRO2 as the QSM method for each subject.

Results

Compared to pre-caffeine, susceptibility increased (5.1±1.1ppb, p<0.01) and CBF decreased (−23.6±6.7ml/100g/min, p<0.01) at 25min post-caffeine in CGM. This corresponded to a CMRO2 of 153.0±26.4µmol/100g/min with an OEF of 33.9±9.6% and 54.5±13.2% (p<0.01) pre- and post- caffeine respectively at CGM, and a CMRO2 of 58.0±26.6µmol/100g/min at white matter. CMRO2 from both QSM and based methods showed good regional consistency (p>0.05), but quantitation of based CMRO2 required an additional scaling factor.

Conclusion

QSM can be used with perfusion measurements pre- and post- caffeine vascoconstriction to map CMRO2 and OEF.

Keywords: Quantitative, CMRO2, OEF, QSM

INTRODUCTION

The cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) and the oxygen extraction fraction (OEF) are important markers for assessing neuronal viability in ischemic stroke when hypoperfusion leads to a compensatory OEF increase to maintain oxygen metabolism before the onset of brain tissue infarction (1–3). Positron emission tomography (PET) using 15O has been used to map CMRO2, but its feasibility as a clinical tool is severely limited by the short half-life (123 sec) of 15O (4) and sparse availability compared to other imaging modalities like MRI.

When oxygen is released from arterial blood to brain tissue, the weakly diamagnetic oxyhemoglobin (oHb) turns into to the strongly paramagnetic deoxyhemoglobin (dHb) in the draining veins (5). MRI is very sensitive to this change in magnetic susceptibility. Changes in R2 (estimated from spin echo data) and (estimated from gradient echo (GRE) data) by the magnetic field of dHb have been used to estimate dHb concentration ([dHb]) (6–11). As is more sensitive than R2 (12), is more commonly used (13–15). However, images are contaminated by blooming artifacts and are highly dependent on imaging parameters including field strength, echo time, voxel size, and object orientation (6,16), making it difficult to quantitatively map [dHb].

Because [dHb] is linearly related to blood magnetic susceptibility that is independent of imaging parameters (17,18), quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM) derived from the magnitude and phase of the GRE signal (19–35) has the potential for quantitative [dHb] measurements. QSM may provide an advantage over the previous approaches by eliminating the blood vessel geometry dependence in estimating [dHb] in veins only (36–40). Here, we demonstrate the feasibility of CMRO2 mapping using QSM and cerebral perfusion measurements.

THEORY

According to mass conservation, we have,

| [1] |

Here CBF is the volumetric cerebral blood flow rate, and [dHb]v and [dHb]a are [dHb] in the draining veins and supplying arteries respectively. The factor 4 accounts for the four oxygen molecules in one oHb, each bound to one of four hemes. CBF can be measured using a quantitative perfusion technique such as arterial spin labeling (ASL) (41). The arterial dHb concentration can be written as [dHb]a = (1 − SaO2) [Hb] with arterial oxygen saturation SaO2 = 0.97 and hemoglobin concentration [Hb] = 2.48µmol/ml for healthy subjects (see Appendix). [dHb]v can be derived using QSM in the following manner by carefully accounting for contributions from various components in blood and non-blood tissue weighted by the respective volume fractions, though the dominant contributions are from venous dHb and tissue ferritin.

The voxel susceptibility, χ, in QSM is linearly proportional to [dHb]v,

| [2] |

Here CBVv = 0.5CBV is the venous blood volume fraction in a voxel assuming blood deoxygenates linearly (10). ψHb = 0.12 is the volume fraction of Hb within blood (see Appendix). XdHb = 10765ppb and XoHb = −813ppb are the volume susceptibilities of pure dHb and oHb respectively (see Appendix). The first term in the right hand side of Eq.2 reflects the susceptibility contribution from venous dHb relative to oxygenated blood. The second term χo in Eq.2 reflects susceptibility contributions from non-blood tissue sources (such as ferritin) χt, pure oxygenated blood Xba, and arterial deoxyhemoglobin:

| [3] |

with CBVa = 1 − CBVv = 0.5CBV, and Xba = ψHb · XoHb + (1 − ψHb)Xp = −131ppb is the volume susceptibility for pure oxygenated blood (Xp = −37.7ppb is blood plasma volume susceptibility) (18,39,42).

With susceptibility (χ) and perfusion (CBV and CBF) measurements, Eqs.1&2 form an equation with two unknowns (CMRO2and χo):

| [4] |

To determine CMRO2, it is necessary to correct for χt, which is independent of blood. This can be achieved using measurements at two different brain perfusion states that have the same CMRO2, such as before and after vasoconstriction in a caffeine challenge (43–45). It is reasonable to assume the non-blood contribution (1 − CBV)χt to susceptibility in a voxel to be the same between the two states. Then Eq.4 leads to

| [5] |

where Δ denotes the difference between the two measurements (see Appendix for a detailed derivation of Eq.5 from Eq.4).

OEF is defined as the oxygen concentration difference between artery and vein scaled by the arterial oxygen concentration (4 * SaO2 [Hb] = 4 * 0.97[Hb]) can then be determined as

| [6] |

METHODS

The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board. Healthy volunteers were recruited (n=13, 13 males, mean age 35 ± 9.5 years) for brain MRI on a 3T scanner (HDxt, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) using an 8-channel receive head coil. All subjects were instructed to avoid caffeine or alcohol intake 24 hours prior to MRI.

Data Acquisition

Given its well-described ability to safely cause measurable reductions in CBF within 30 minutes upon administration (45), a bolus of caffeine (~200 mg caffeine in black coffee) was administered orally through a flexible plastic tube to minimize head motion. MRI was performed before and 25 min after the oral administration of the caffeine challenge, using a protocol consisting of an anatomical T2 weighted 2D fast spin echo (FSE) sequence, a 3D FSE ASL sequence to measure CBF, and a 3D spoiled GRE sequence to measure magnitude and phase, from which QSM maps were calculated using dipole inversion algorithm (19,21). The total scan time was approximately 60 min (consisting of 15 min scan before caffeine administration to 45 min after).

The T2 weighted axial 2D FSE parameters were: 82 ms TE, 4250 ms TR, 22 cm FOV, 0.46 × 0.46 mm2 in-plane resolution, 3mm slice thickness, 46 slices, 23 echo train length (ETL), 2 signal averages, and 5 min scan time.

The 3D FSE ASL sequence parameters were: 1500 ms labeling period, 1525 ms post-label delay, spiral sampling of 8 interleaves with 512 readout points per leaf, 62.5 kHz readout bandwidth, 1 ETL, 3 mm isotropic resolution and identical volume coverage as the T2 weighted sequence, 10.5 ms TE, 4796 ms TR, 3 signal averages, and 6 min scan time. maps (ml/100g/min) were generated from the ASL data using the FuncTool software package (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA).

The 3D spoiled GRE sequence parameters included: 11 equally spaced echoes, 4.4 ms first TE, 4.9 ms echo spacing, 58.5 ms TR, 0.46 mm in-plane resolution, 3 mm slice thickness, and identical volume coverage as the T2 weighted sequence, 62.5 kHz readout bandwidth, 15° flip angle, and 7 min scan time. The pulse sequence was flow-compensated in the readout (anterior-posterior) direction.

Image Processing

QSM maps were calculated from GRE magnitude and phase data. A Gauss-Newton nonlinear estimation of the field map was performed (33), followed by unwrapping (46) and background field removal using a projection onto dipole fields method (47) to obtain the local field map, from which tissue susceptibility was computed using the Morphology Enabled Dipole Inversion (MEDI) algorithm (20,33). maps were generated from GRE magnitude data via voxel-by-voxel fitting using auto-regression on linear operations (ARLO) monoexponential fitting algorithm (48). Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of QSM and maps were estimated as the ratio of mean over standard deviation of values measured in the caudate nucleus.

Grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) masks were created using the FSL FAST algorithm on pre-caffeine CBF images covering the supratentorial brain parenchyma from the vertex to the superior aspect of the cerebellum (49). These masks were visually confirmed by a board-certified attending neuroradiologist (A.G.) for anatomical accuracy. The cortical GM mask was further segmented by the same neuroradiologist into six vascular territories (VT, left and right anterior cerebral artery (ACA), middle cerebral artery (MCA) and posterior cerebral artery (PCA)) (Fig.1). For this feasibility study, pre-caffeine CBV was estimated from CBF based on the linear regression equations derived from 15O steady-state inhalation PET (50): CBV = (0.227CBF − 7.27)/100 within the GM mask, and CBV = (0.0316CBF + 1.9447)/100 within the WM mask. Post-caffeine CBV was estimated from pre-caffeine CBV using Grubb’s exponent of α = 0.38 (51) for both masks. CMRO2 maps of GM and WM were then calculated from pre- and post-caffeine QSM and CBF/CBV measurements by solving Eq.4 using a conjugate gradient method. The resulting maps were combined to obtain the final CMRO2 maps of the whole brain. OEF maps were then calculated using Eq.8. Gaussian smoothing (2.1 mm kernel) was used to reduce noise in the CMRO2 and OEF maps.

Figure 1.

Example of GM and WM masks on a mid-brain slice. The GM mask is segmented into six regions corresponding to different vascular territories as shown. The masks cover the supratentorial brain parenchyma from the vertex to the superior aspect of the cerebellum.

All images were co-registered and interpolated to the resolution of the maps using the FSL FLIRT algorithm (52,53). QSM values were referenced to the susceptibility of water (defined in this study as the mean susceptibility of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the lateral ventricles).

CMRO2 was also estimated using a calibrated fMRI approach based on (13–15). The difference in between pre- and post- caffeine challenge can be used to estimate the dHb component of in a voxel during pre-caffeine state () according to the following equation with Grubb’s α = 0.38 and an empirical β = 1.5 (54).

| [7] |

Then the relationship between and pre-caffeine venous dHb concentration [dHb]v,pre is given as follow (7,8,11,54,55):

| [8] |

Combining Eqs.7&8 with Eq.1 and using [dHb]a ≈ 0 and , we have

| [9] |

This based CMRO2 method requires the scaling factor A to be measured separately with an additional measurement at a different brain state (13–15). For this feasibility study, the regional consistency of CMRO2 maps within cortical GM ROIs (Fig.1) derived from QSM and based methods was compared under the assumption that their global averages or total CMRO2 were the same for each subject, which allowed A to be determined from the QSM data without further experiment.

Statistical Analysis

For each ROI, the mean and standard deviation of QSM, CBF, OEF, and CMRO2 values as well as the corresponding left/right (L/R) hemisphere ratio were measured for both the QSM based and based method. Paired-sample t-tests were performed to assess the differences in QSM, , CBF, and OEF in the GM ROIs before and after the caffeine challenge across the subjects. PET studies have shown that CMRO2 and OEF maps are homogeneous in GM across the brain and exhibit left-right symmetry in healthy subjects (50,56). Paired-sample t-tests were performed to compare CMRO2 in the VT ROIs between QSM based and based method to analyze their consistency. To analyze the symmetry of the images, analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the significance of differences in L/R hemisphere ratio of CMRO2 and OEF among the VT ROIs. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. All data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation.

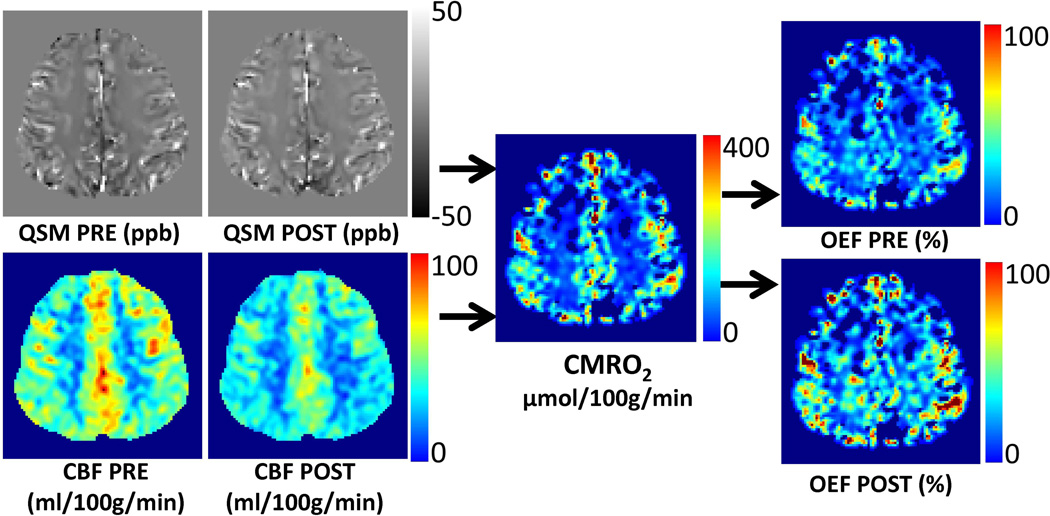

RESULTS

All scans were completed successfully. The average GM volume for each vascular territory was 125.8 ± 17.7 mL (ACA, both left and right), 254.0 ± 25.4 mL (MCA), and 79.7 ± 14.2 mL (PCA) (n=13). Figure 2 shows an example of pre- and post-caffeine QSM and CBF maps and the calculated CMRO2 and OEF maps. QSM and maps have similar SNR (6.2 ± 1.9 vs. 7.2 ± 1.6, p>0.05). Figure 3 shows OEF and CMRO2 maps across the brain volume, illustrating good GM and white matter contrast in reasonable agreement with T2 weighted images. Compared to the pre-caffeine values, a statistically significant increase in QSM (5.1 ± 1.1 ppb, p<0.01), (1.5 ± 0.3 s−1, p<0.01), and decrease in CBF (−23.6 ± 6.7 ml/100g/min, p<0.01) were measured in the global cortical GM ROI at 25 min post-caffeine. Consistent with the decrease in CBF after the caffeine challenge, OBF significantly increased from 33.9 ± 9.6% to 54.5 ± 13.2% (p<0.01) at 25 min post-caffeine. The mean CMRO2 in the global cortical GM ROI calculated using QSM were 153.0 ± 26.4 µmol/100g/min. The mean CMRO2, and pre- and post-caffeine OEF measured in the WM were 58.0 ± 26.6 µmol/100g/min, 26.3 ± 11.7% and 45.0 ± 18.7%, respectively.

Figure 2.

An example of QSM and CBF maps acquired pre- and post-caffeine and the derived CMRO2 and OEF maps in a healthy subject (subject 12).

Figure 3.

An example of volumetric pre- and post-caffeine OEF and CMRO2 maps using the QSM-based method, and T2 weighted images of a healthy subject (subject 7). The locations of the slices are marked on the scout images shown on the right.

Figure 4 compares CMRO2 maps obtained from two other subjects using QSM-based and -based methods. The mean in the global cortical GM ROI was 1.9 ± 0.8 s−1. Table 1 shows the CMRO2 measured within VT ROIs of QSM based and based methods, demonstrating good agreement within all vascular territories (all differences were statistically non-significant). Table 2 shows the L/R hemisphere ratio of CMRO2 and OEF measured within the VT ROIs. Both the QSM and method show statistically comparable L/R hemisphere ratio values among vascular territories ranging from 0.92 to 1.07, indicating good hemispheric symmetry. (ANOVA, p > 0.05).

Figure 4.

Examples of QSM- and R2* -based CMRO2 maps of two representative subjects (subject 1 and 4). The locations of the slices are marked on the scout images.

Table 1.

QSM and based CMRO2 measurements within cortical GM regions associated with different vascular territories (µmol/100g/min, mean ± std). All differences between the two methods were statistically non-significant (p>0.05).

| QSM based | based | |

|---|---|---|

| ACA_Left | 175.5 ± 33.4 | 166.2 ± 29.9 |

| ACA_Right | 174.1 ± 33.6 | 160.6 ± 29.5 |

| MCA_Left | 149.3 ± 27.1 | 153.2 ± 42.1 |

| MCA_Right | 154.8 ± 37.7 | 144.8 ± 33.6 |

| PCA_Left | 143.9 ± 38.0 | 159.1 ± 39.8 |

| PCA_Right | 140.8 ± 32.8 | 157.0 ± 38.3 |

Table 2.

L/R hemisphere ratio of QSM and based CMRO2 and OEF values measured within cortical GM regions. No statistical significance has been found (p>0.05) among vascular territory within each method.

| OEF Pre-Caffeine | OEF Post-Caffeine | CMRO2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QSM based | R2* based | QSM based | R2* based | QSM based | R2* based | |

| ACA | 0.99 ± 0.12 | 1.00 ± 0.13 | 0.99 ± 0.13 | 1.02 ± 0.15 | 1.03 ± 0.21 | 1.04 ± 0.15 |

| MCA | 0.99 ± 0.25 | 0.99 ± 0.23 | 0.97 ± 0.24 | 0.97 ± 0.26 | 1.00 ± 0.22 | 1.07 ± 0.23 |

| PCA | 0.94 ± 0.13 | 0.96 ± 0.19 | 0.92 ± 0.13 | 0.92 ± 0.15 | 1.03 ± 0.15 | 1.03 ± 0.23 |

DISCUSSION

Our preliminary results demonstrate the in vivo feasibility of 3D CMRO2 brain mapping using the recently developed QSM and quantitative perfusion. The QSM based CMRO2 of 153.0 ± 26.4 µmol/100g/min in cortical GM agrees well with values reported in the MRI and PET literature (13–15,50,56). The QSM based CMRO2 is consistent with the based CMRO2 (our mean of 1.9 ± 0.8 s−1 is in agreement with values in calibrated fMRI literature (13,57–60)). Using measurements at two different brain states (pre- and post- caffeine challenge here), the QSM based CMRO2 method can provide absolute quantitation while the based CMRO2 method relies on the additional measurement of a scaling factor.

The model for blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal (Eqs.7&8) have been used extensively to study neural function and oxygen metabolism in calibrated fMRI (13–15,55,61). For quantitation of venous dHb concentration [dHb]v required for CMRO2, the model determines [dHb]v up to a constant A (Eqs.7&8), which is a disadvantage compared to the absolute quantitation of [dHb]v by the QSM based method (Eq.2). This may be explained by the underlying physics for and QSM. QSM solves the field to susceptibility source inverse problem based on Maxwell’s equation (21) using the phase of the gradient echo data. Magnetic susceptibility has a well-defined quantitative relationship with [dHb]v (Eq.2). On the other hand, is the decay rate of gradient echo magnitude signal and may be approximated as the variance of the field in a voxel (6,34,62). Its relationship with [dHb]v is empirical and depends on a scaling factor that requires additional information to be determined (8,11,55). The calculation of the field variance requires input of detailed field pattern in a voxel that is not known, which is the fundamental cause of this indeterminacy of the model. Measurements at a third brain state can estimate this scaling factor, which is why 3 brain states (normoxic, hyperoxic and hypercapnia) have been used in based CMRO2 mapping (13–15). Additionally, the empirical parameter β~1.5 may be spatially varying (63), as β~1 for voxels containing larger vessels (6) and β~2 for voxels containing capillaries (7,61). This may explain the greater difference between QSM and based CMRO2 measurements in regions with large vessels such as the posterior region near the large sagittal sinus (PCA in Table 1). Furthermore, Eqs.7&8 may not properly account for the ferritin (non-heme iron) contribution to , possibly causing overestimation of CMRO2 in the basal ganglia area with known high ferritin concentration (Fig.4c). Besides requiring fewer drug challenges, QSM based CMRO2 offer other potential benefits such as reduced blooming artifacts near the air-tissue interface and improved robustness against changes in scanning parameters (64).

The voxel size used in this work was chosen mainly based on scan time and SNR considerations. In general, SNR is dictated by scan time, which in this study was kept comparable to that used in routine MRI (6 min for 3D ASL (65) and 7 min for QSM (66)) with the aim to prevent head motion and also to keep the total experiment time under 1 hour. As a result, the achievable spatial resolution for the ASL scan was 3 mm isotropic, which is lower than that of the QSM scan (0.5×0.5×3 mm3). The derived CMRO2 and OEF maps therefore also have a 3 mm isotropic resolution, although due to the very small change in the observable MR signal between the two brain states we found that reliable quantitative analysis can be performed only with region-based (instead of voxel-based) measurements. This is a limitation of the current work and solutions for SNR improvement require further investigation.

In this work, several physiological parameters such as arterial oxygenation saturation level (SaO2) and total hemoglobin concentration (ψHb = 0.12) were assumed fixed for all subjects (see Appendix). In clinical practice, these parameters can be measured for each individual subject using highly automated devices: SaO2 be obtained through pulse oximetry (67), and ψHb can be measured directly using hemoximetry or estimated from hematocrit measurement. In healthy subjects, SaO2 and ψHb can range from 0.95 to 0.99 and 0.096 to 0.14 (68). Within these ranges, error propagation analysis showed a worst-case deviation of 11% from CMRO2 obtained in GM with fixed SaO2 and ψHb values, which suggests that our method is fairly robust against changes in these physiological parameters.

While previous works have reported similar OEF over the whole brain (69,70), we found that OEFs were slightly lower in WM than in GM (26.3 ±11.7% vs. 33.9 ± 9.6% pre-caffeine, and 45.0 ± 18.7% vs. 54.5 ± 13.2% post-caffeine, p<0.05). The observed discrepancy between WM and GM regions may be attributed to the challenges associated with accurately mapping the relationship between CBF and CBV in each region, which was derived empirically from normative PET data (50). A separate measurement of CBV may be performed using a dynamic susceptibility contrast, or a dynamic QSM method (71) and extracellular contrast agents that clear rapidly before the administration of caffeine, unless it is performed as the last scan.

In this work, CSF was used to provide the reference value for brain parenchymal susceptibility. To overcome the effect of CSF flow, our GRE pulse sequence was flow-compensated in the readout (anterior-posterior) direction. When compared to a fully compensated pulse sequence (72) in three of our subjects, we found that the difference in susceptibility of the CSF (measured in lateral ventricles) was relatively small (4.1 ± 3.7 ppb, p>0.05). Further work is needed to study the effect of CSF flow on QSM and CMRO2 accuracy.

Caffeine administration has been shown to have no significant change in CMRO2 (45). Other CMRO2-invariant brain challenges may include hypercapnia and hyperoxia, which may have risks and discomforts associated with the prolonged (>10min) continuous inhalation of high concentration CO2 and O2 necessary for the data acquisition. In addition, this feasibility study lacks the second challenge for estimating coefficient in calibrated BOLD. Further work is warranted to compare the proposed QSM-based with the existing based methods that include the additional hyperoxia or hypercapnia challenges.

CONCLUSION

Quantitative susceptibility mapping can be used in conjunction with cerebral perfusion measurements before and after a vasoconstricting caffeine challenge to map cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen consumption and oxygen extraction fraction.

Acknowledgments

Funding information:NIH grants R01EB013443, R01NS072370 and R43EB015293.

APPENDIX

Here we provide detailed derivation of Eq. 5 from Eq. 4 and estimation of parameters related to blood.

Derivation of Eq. 5 from Eq. 4

Eq. 4 is

| [4] |

Moving χ − χoto the left side, we have:

| [4a] |

Equation 4a applies to each of the two brain states (pre- and post-caffeine), the difference of which can be written as:

| [4b] |

By rearranging Eq.4b, we arrive at Eq.5:

| [5] |

Calculation of hemoglobin molar concentration in blood [Hb]

The hemoglobin molar concentration in blood [Hb] = 2.48 µmol/ml, is estimated from the Hematrocrit Hct = 0.47 (68), Hb mass concentration in a RBC (0.34 g/ml), and the molar mass of dHb MHb = 64450 × 10−6g/µmol (73)

Calculation of hemoglobin volume fraction in blood in blood ψHb

The hemoglobin volume fraction in blood ψHb = 0.12 is estimated from [Hb] MHb, and Hb concentration in pure aggregate (ρHb = 1.335g/ml) (74).

Calculation of oxyhemoglobin XoHb and deoxyHemoglobin XdHb volume susceptibility

The volume susceptibility of oxyhemoglobins XoHb relative to water is estimated from the reported mass susceptibility of globin relative to vacuum, −4π (0.587 × 10−6 mL/g) (4π for conversion from cgs to si) (74,75) as,

where − 9035 ppb is the volume susceptibility of water with respect to vacuum (76).

The volume susceptibility of oxyhemoglobins XdHb relative to water is estimated by adding to XoHb a paramagnetic term of 5.25 µB (Bohr magneton µB = 9.274 × 10−24 J/T) per heme (77,78) according to (18,34,79),

where NA = 6.02 × 1023 mol−1 is the Avogadro number, µ0 = 4π × 10−7 Tm/A is the magnetic permeability in vacuum, KB = 1.38 × 10−23 J/K is the Boltzman constant, and T = 310 K is the human body temperature.

REFERENCES

- 1.Derdeyn CP, Videen TO, Yundt KD, Fritsch SM, Carpenter DA, Grubb RL, Powers WJ. Variability of cerebral blood volume and oxygen extraction: stages of cerebral haemodynamic impairment revisited. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2002;125(Pt 3):595–607. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, Chazen JL, Hartman M, Delgado D, Anumula N, Shao H, Mazumdar M, Segal AZ, Kamel H, Leifer D, Sanelli PC. Cerebrovascular reserve and stroke risk in patients with carotid stenosis or occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43(11):2884–2891. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.663716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta A, Baradaran H, Schweitzer AD, Kamel H, Pandya A, Delgado D, Wright D, Hurtado-Rua S, Wang Y, Sanelli PC. Oxygen extraction fraction and stroke risk in patients with carotid stenosis or occlusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJNR American journal of neuroradiology. 2014;35(2):250–255. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mintun MA, Raichle ME, Martin WR, Herscovitch P. Brain oxygen utilization measured with O-15 radiotracers and positron emission tomography. J Nucl Med. 1984;25(2):177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauling L, Coryell CD. The Magnetic Properties and Structure of Hemoglobin, Oxyhemoglobin and Carbonmonoxyhemoglobin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1936;22(4):210–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yablonskiy DA, Haacke EM. Theory of NMR signal behavior in magnetically inhomogeneous tissues: the static dephasing regime. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1994;32(6):749–763. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910320610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ellermann JM, Ugurbil K. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophys J. 1993;64(3):803–812. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boxerman JL, Bandettini PA, Kwong KK, Baker JR, Davis TL, Rosen BR, Weisskoff RM. The intravascular contribution to fMRI signal change: Monte Carlo modeling and diffusion-weighted studies in vivo. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;34(1):4–10. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu H, Ge Y. Quantitative evaluation of oxygenation in venous vessels using T2-Relaxation-Under-Spin-Tagging MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60(2):357–363. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Zijl PC, Eleff SM, Ulatowski JA, Oja JM, Ulug AM, Traystman RJ, Kauppinen RA. Quantitative assessment of blood flow, blood volume and blood oxygenation effects in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Med. 1998;4(2):159–167. doi: 10.1038/nm0298-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kennan RP, Zhong J, Gore JC. Intravascular susceptibility contrast mechanisms in tissues. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1994;31(1):9–21. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910310103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bandettini PA, Wong EC, Jesmanowicz A, Hinks RS, Hyde JS. Spin-echo and gradient-echo EPI of human brain activation using BOLD contrast: a comparative study at 1.5 T. NMR in biomedicine. 1994;7(1–2):12–20. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940070104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulte DP, Kelly M, Germuska M, Xie J, Chappell MA, Okell TW, Bright MG, Jezzard P. Quantitative measurement of cerebral physiology using respiratory-calibrated MRI. NeuroImage. 2012;60(1):582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gauthier CJ, Hoge RD. Magnetic resonance imaging of resting OEF and CMRO(2) using a generalized calibration model for hypercapnia and hyperoxia. NeuroImage. 2012;60(2):1212–1225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wise RG, Harris AD, Stone AJ, Murphy K. Measurement of OEF and absolute CMRO2: MRI-based methods using interleaved and combined hypercapnia and hyperoxia. NeuroImage. 2013;83:135–147. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Chang S, Liu T, Wang Q, Cui D, Chen X, Jin M, Wang B, Pei M, Wisnieff C, Spincemaille P, Zhang M, Wang Y. Reducing the object orientation dependence of susceptibility effects in gradient echo MRI through quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;68(5):1563–1569. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain V, Abdulmalik O, Propert KJ, Wehrli FW. Investigating the magnetic susceptibility properties of fresh human blood for noninvasive oxygen saturation quantification. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;68(3):863–867. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spees WM, Yablonskiy DA, Oswood MC, Ackerman JJ. Water proton MR properties of human blood at 1.5 Tesla: magnetic susceptibility, T(1), T(2), T*(2), and non-Lorentzian signal behavior. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2001;45(4):533–542. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu J, Liu T, de Rochefort L, Ledoux J, Khalidov I, Chen W, Tsiouris AJ, Wisnieff C, Spincemaille P, Prince MR, Wang Y. Morphology enabled dipole inversion for quantitative susceptibility mapping using structural consistency between the magnitude image and the susceptibility map. NeuroImage. 2012;59(3):2560–2568. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu T, Liu J, de Rochefort L, Spincemaille P, Khalidov I, Ledoux JR, Wang Y. Morphology enabled dipole inversion (MEDI) from a single-angle acquisition: comparison with COSMOS in human brain imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2011;66(3):777–783. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Rochefort L, Liu T, Kressler B, Liu J, Spincemaille P, Lebon V, Wu J, Wang Y. Quantitative susceptibility map reconstruction from MR phase data using bayesian regularization: validation and application to brain imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2010;63(1):194–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li W, Wu B, Liu C. Quantitative susceptibility mapping of human brain reflects spatial variation in tissue composition. NeuroImage. 2011;55(4):1645–1656. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schweser F, Deistung A, Sommer K, Reichenbach JR. Toward online reconstruction of quantitative susceptibility maps: superfast dipole inversion. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(6):1582–1594. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Rochefort L, Brown R, Prince MR, Wang Y. Quantitative MR susceptibility mapping using piece-wise constant regularized inversion of the magnetic field. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60(4):1003–1009. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kressler B, de Rochefort L, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Jiang Q, Wang Y. Nonlinear regularization for per voxel estimation of magnetic susceptibility distributions from MRI field maps. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2010;29(2):273–281. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2023787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wharton S, Bowtell R. Whole-brain susceptibility mapping at high field: a comparison of multiple- and single-orientation methods. NeuroImage. 2010;53(2):515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu B, Li W, Guidon A, Liu C. Whole brain susceptibility mapping using compressed sensing. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;67(1):137–147. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu T, Spincemaille P, de Rochefort L, Kressler B, Wang Y. Calculation of susceptibility through multiple orientation sampling (COSMOS): a method for conditioning the inverse problem from measured magnetic field map to susceptibility source image in MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61(1):196–204. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilgic B, Pfefferbaum A, Rohlfing T, Sullivan EV, Adalsteinsson E. MRI estimates of brain iron concentration in normal aging using quantitative susceptibility mapping. NeuroImage. 2012;59(3):2625–2635. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Leigh JS. Quantifying arbitrary magnetic susceptibility distributions with MR. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2004;51(5):1077–1082. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Haacke EM, Cheng NY, House MJ, Liu Q, Neelavalli J, Ogg RJ, Khan A, Ayaz M, Kirsch W, Obenaus A. Imaging iron stores in the brain using magnetic resonance imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging. 2005;23(1):1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shmueli K, de Zwart JA, van Gelderen P, Li TQ, Dodd SJ, Duyn JH. Magnetic susceptibility mapping of brain tissue in vivo using MRI phase data. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;62(6):1510–1522. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T, Wisnieff C, Lou M, Chen W, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. Nonlinear formulation of the magnetic field to source relationship for robust quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2013;69(2):467–476. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang Y. Principles of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: physics concepts, pulse sequences & biomedical applications. 2012 Oct 3; www.createspace.com/4001776. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Y, Liu T. Quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM): Decoding MRI data for a tissue magnetic biomarker. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haacke EM, Lai S, Reichenbach JR, Kuppusamy K, Hoogenraad FG, Takeichi H, Lin W. In vivo measurement of blood oxygen saturation using magnetic resonance imaging: a direct validation of the blood oxygen level-dependent concept in functional brain imaging. Human brain mapping. 1997;5(5):341–346. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:5<341::AID-HBM2>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan AP, Benner T, Bolar DS, Rosen BR, Adalsteinsson E. Phase-based regional oxygen metabolism (PROM) using MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;67(3):669–678. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li C, Langham MC, Epstein CL, Magland JF, Wu J, Gee J, Wehrli FW. Accuracy of the cylinder approximation for susceptometric measurement of intravascular oxygen saturation. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2012;67(3):808–813. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan AP, Bilgic B, Gagnon L, Witzel T, Bhat H, Rosen BR, Adalsteinsson E. Quantitative oxygenation venography from MRI phase. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;72(1):149–159. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wehrli FW, Rodgers ZB, Jain V, Langham MC, Li C, Licht DJ, Magland J. Time-resolved MRI oximetry for quantifying CMRO(2) and vascular reactivity. Academic radiology. 2014;21(2):207–214. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Detre JA, Leigh JS, Williams DS, Koretsky AP. Perfusion imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;23(1):37–45. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weisskoff RM, Kiihne S. MRI susceptometry: image-based measurement of absolute susceptibility of MR contrast agents and human blood. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1992;24(2):375–383. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910240219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lunt MJ, Ragab S, Birch AA, Schley D, Jenkinson DF. Comparison of caffeine-induced changes in cerebral blood flow and middle cerebral artery blood velocity shows that caffeine reduces middle cerebral artery diameter. Physiol Meas. 2004;25(2):467–474. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/25/2/006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cameron OG, Modell JG, Hariharan M. Caffeine and human cerebral blood flow: a positron emission tomography study. Life sciences. 1990;47(13):1141–1146. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(90)90174-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perthen JE, Lansing AE, Liau J, Liu TT, Buxton RB. Caffeine-induced uncoupling of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism: a calibrated BOLD fMRI study. NeuroImage. 2008;40(1):237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cusack R, Papadakis N. New robust 3-D phase unwrapping algorithms: application to magnetic field mapping and undistorting echoplanar images. NeuroImage. 2002;16(3 Pt 1):754–764. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu T, Khalidov I, de Rochefort L, Spincemaille P, Liu J, Tsiouris AJ, Wang Y. A novel background field removal method for MRI using projection onto dipole fields (PDF) NMR in biomedicine. 2011;24(9):1129–1136. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pei M, Nguyen TD, Thimmappa ND, Salustri C, Dong F, Cooper MA, Li J, Prince MR, Wang Y. Algorithm for fast monoexponential fitting based on Auto-Regression on Linear Operations (ARLO) of data. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25137. 10.1002/mrm.25137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE transactions on medical imaging. 2001;20(1):45–57. doi: 10.1109/42.906424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leenders KL, Perani D, Lammertsma AA, Heather JD, Buckingham P, Healy MJ, Gibbs JM, Wise RJ, Hatazawa J, Herold S, et al. Cerebral blood flow, blood volume and oxygen utilization. Normal values and effect of age. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1990;113(Pt 1):27–47. doi: 10.1093/brain/113.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grubb RL, Jr, Raichle ME, Eichling JO, Ter-Pogossian MM. The effects of changes in PaCO2 on cerebral blood volume, blood flow, and vascular mean transit time. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 1974;5(5):630–639. doi: 10.1161/01.str.5.5.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage. 2002;17(2):825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoge RD, Atkinson J, Gill B, Crelier GR, Marrett S, Pike GB. Investigation of BOLD signal dependence on cerebral blood flow and oxygen consumption: the deoxyhemoglobin dilution model. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1999;42(5):849–863. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2594(199911)42:5<849::aid-mrm4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buxton RB, Uludag K, Dubowitz DJ, Liu TT. Modeling the hemodynamic response to brain activation. NeuroImage. 2004;23(Suppl 1):S220–S233. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ito H, Kanno I, Kato C, Sasaki T, Ishii K, Ouchi Y, Iida A, Okazawa H, Hayashida K, Tsuyuguchi N, Ishii K, Kuwabara Y, Senda M. Database of normal human cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, cerebral oxygen extraction fraction and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen measured by positron emission tomography with 15O-labelled carbon dioxide or water, carbon monoxide and oxygen: a multicentre study in Japan. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;31(5):635–643. doi: 10.1007/s00259-003-1430-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ances BM, Leontiev O, Perthen JE, Liang C, Lansing AE, Buxton RB. Regional differences in the coupling of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism changes in response to activation: implications for BOLD-fMRI. NeuroImage. 2008;39(4):1510–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ances BM, Liang CL, Leontiev O, Perthen JE, Fleisher AS, Lansing AE, Buxton RB. Effects of aging on cerebral blood flow, oxygen metabolism, and blood oxygenation level dependent responses to visual stimulation. Human brain mapping. 2009;30(4):1120–1132. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bulte DP, Drescher K, Jezzard P. Comparison of hypercapnia-based calibration techniques for measurement of cerebral oxygen metabolism with MRI. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61(2):391–398. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen Y, Parrish TB. Caffeine dose effect on activation-induced BOLD and CBF responses. NeuroImage. 2009;46(3):577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Blockley NP, Griffeth VE, Simon AB, Buxton RB. A review of calibrated blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) methods for the measurement of task-induced changes in brain oxygen metabolism. NMR in biomedicine. 2013;26(8):987–1003. doi: 10.1002/nbm.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y. Quantitative Susceptibility Mapping: Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Tissue Magnetism. 2013 Jun; www.createspace.com/4346993. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Davis TL, Kwong KK, Weisskoff RM, Rosen BR. Calibrated functional MRI: mapping the dynamics of oxidative metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(4):1834–1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu T, Surapaneni K, Lou M, Cheng L, Spincemaille P, Wang Y. Cerebral microbleeds: burden assessment by using quantitative susceptibility mapping. Radiology. 2012;262(1):269–278. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong AM, Yan FX, Liu HL. Comparison of three-dimensional pseudo-continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion imaging with gradient-echo and spin-echo dynamic susceptibility contrast MRI. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI. 2014;39(2):427–433. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Langkammer C, Liu T, Khalil M, Enzinger C, Jehna M, Fuchs S, Fazekas F, Wang Y, Ropele S. Quantitative susceptibility mapping in multiple sclerosis. Radiology. 2013;267(2):551–559. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12120707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gehring H, Duembgen L, Peterlein M, Hagelberg S, Dibbelt L. Hemoximetry as the "gold standard"? Error assessment based on differences among identical blood gas analyzer devices of five manufacturers. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007;105(6 Suppl):S24–S30. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000268713.58174.cc. tables of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hoffman R, Bussel JB, Cushing MM, Giardina PJ. Hematology : basic principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2009. p. xxvii.p. 2523. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gusnard DA, Raichle ME, Raichle ME. Searching for a baseline: functional imaging and the resting human brain. Nature reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2(10):685–694. doi: 10.1038/35094500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.He X, Zhu M, Yablonskiy DA. Validation of oxygen extraction fraction measurement by qBOLD technique. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;60(4):882–888. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu B, Spincemaille P, Liu T, Prince MR, Dutruel S, Gupta A, Thimmappa ND, Wang Y. Quantification of cerebral perfusion using dynamic quantitative susceptibility mapping. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu B, Liu T, Spincemaille P, Prince M, Wang Y. Flow compensated quantitative susceptibility mapping for venous oxygenation imaging. Magnetic resonance in medicine : official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine / Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2014;72(2):438–445. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dickerson RE, Geis I. Hemoglobin : structure, function, evolution, and pathology. Menlo Park, Calif.: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co.; 1983. p. 176. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Savicki JP, Lang G, Ikeda-Saito M. Magnetic susceptibility of oxy- and carbonmonoxyhemoglobins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81(17):5417–5419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.17.5417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cerdonio M, Morante S, Torresani D, Vitale S, DeYoung A, Noble RW. Reexamination of the evidence for paramagnetism in oxy- and carbonmonoxyhemoglobins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(1):102–103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.1.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.CRC standard mathematical tables. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press; 1987. Chemical Rubber Company. p v. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pauling L. General Chemistry. Dover Publications; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pauling L, Coryell CD. The Magnetic Properties and Structure of Hemoglobin, Oxyhemoglobin and Carbonmonoxyhemoglobin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1936;22(4):210–216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.22.4.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McDermott A. Structure and dynamics of membrane proteins by magic angle spinning solid-state NMR. Annual review of biophysics. 2009;38:385–403. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.050708.133719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]