Abstract

It is recommended that for effective utilization of spent hen meat, it should be converted into value added or shelf stable meat products. Since we are lacking in cold chain facilities, therefore there is imperative need to develop shelf stable meat products. The present study was envisaged with the objective to develop dehydrated chicken meat rings utilizing spent hen meat with different extenders. A basic formulation and processing conditions were standardized for dehydrated chicken meat rings. Extenders such as rice flour, barnyard millet flour and texturized soy granule powder at 5, 10 and 15 % levels were incorporated separately replacing the lean meat in pre standardized dehydrated chicken meat ring formulation. On the basis of physico-chemical properties and sensory scores optimum level of incorporation was adjudged as 10 %, 10 % and 5 % for rice flour, barnyard millet flour and texturized soy granule powder respectively. Products with optimum level of extenders were analysed for physico-chemical and sensory attributes. It was found that a good quality dehydrated chicken meat rings can be prepared by utilizing spent hen meat at 90 % level, potato starch 3 % and refined wheat flour 7 % along with spices, condiments, common salt and STPP. Addition of an optimum level of different extenders such as rice flour (10 %), barnyard millet flour (10 %) and TSGP (5 %) separately replacing lean meat in the formulation can give acceptable quality of the product. Rice flour was found to be the best among the three extenders studied as per the sensory evaluation.

Keywords: Spent hen, Dehydrated meat rings, Extenders, Sensory evaluation, Physico-chemical characteristics

Introduction

India has a chicken population of about 613 million (FAO 2009), which contributes immensely to country’s economy through egg and broiler production. India stands fifth in the world in chicken meat production with a figure of 0.68 million tonnes (FAO 2009). Due to cost competitiveness, nutritional quality, universal availability and absence of religious taboos, the chicken meat occupies important components of Indian non- vegetarian diet.

As a result of tremendous growth in layer industry, the spent hen availability has increased many folds in the preceding years. Although it is a good protein source, spent hens have minimal economic values. Because of higher collagen content, the spent hen meat is very tough in comparison to those of broilers and roasters and so is not well accepted by the consumers. It has been utilized primarily for chicken soups and emulsified products. Therefore, additional usages need to be developed to increase the value of the spent hen meat.

Due to the intrinsic properties of fresh meat like relatively high water activity, slightly acidic pH and the availability of carbohydrate (glycogen) and proteins, it becomes a good substrate for microbial growth and consequently a highly perishable commodity. The shelf life of meat products is limited by enzymatic and microbiological spoilage. Their high perishability causes their storage and marketing demanding considerable amount of energy input, in terms of refrigeration and freezing, which is costly and scanty in India and other developing countries.

Shelf life of meat and meat products can be enhanced by applying various preservation methods. Drying is one of the oldest methods of food preservation and is a very important aspect of food processing (Vadivambal and Jayas 2007). It can be defined as a simultaneous heat and mass transfer operation in which water activity of material is lowered by removal of water to a certain level so that microbial spoilage is avoided. Dried food products are preferred as they require less storage space, no cold chain facility, are easy to transport and useful in natural disasters such as cyclones, floods and earthquakes. Dried meat and meat products may play an important role in providing protein rich food to under nourished people in underdeveloped and developing nations. Drying of meat has been practised since time immemorial. Drying of meat under sun is still followed in many places of India and many underdeveloped countries. But it is a time consuming process and exposes meat to contamination from air, which contains aerosolized microbes, especially moulds and spores. This contamination can be avoided by drying meat in mechanical dryers. Sharp (1953) proposed that the term ‘dehydrated’ be used to denote drying carried out under technically controlled conditions independent of external climatic conditions. Convective drying of food products is extensively employed as a preservation technique. Oven drying is the simplest way to dry foods. It is also faster than the sun drying or using a food dryer. Dried, desiccated or low moisture foods are those that generally do not contain more than 25 % moisture and have a aw between 0.00 and 0.60. These are the traditional dried foods. Another group of shelf stable foods are those that contain moisture between 15 and 50 % and aw between 0.60 and 0.85, known as the intermediate moisture foods (Jay et al.2005).

Increasing interest is being shown in partial replacement of meat systems with extenders/binders/fillers in order to minimize the product cost while improving or at least maintaining nutritional and sensory qualities of end products that consumers expect. Cereals, millets and non meat proteins added to meat products as extenders improve yield, texture, palatability and reduce the cost of production.

Research studies have been conducted on dried/shelf stable ready to eat meat products but not much on dehydrated chicken meat products that could be rehydrated and used after cooking. In view of the above facts, the present research study was planned with the objective to develop and evaluate dehydrated ready to cook (RTC) meat rings from spent hen meat using different extenders. This product may be consumed as a snack/breakfast item after rehydration and steam cooking and also in curry.

Materials and methods

Spent hen meat

Dressed broiler spent hens (more than 50 weeks old) were obtained from Central Avian Research Institute (CARI), Izatnagar, and these were deboned manually in the experimental abattoir of Livestock Products Technology (LPT) Division of Indian Veterinary Research Institute (IVRI), Izatnagar for use in preparation of dehydrated chicken meat rings. All separable fat, fascia and connective tissue, were trimmed off and lean meat was packed in polyethylene bags, and frozen at −20 °C till further use.

Preliminary experiments

A series of preliminary trials was conducted to standardize the basic formulation and processing conditions the preparation of dehydrated chicken meat rings from spent hen meat. Different processes and formulations to prepare an acceptable quality ready to cook dehydrated chicken meat rings were tried and finally, the basic formulation and processing conditions/preparation methodology as mentioned under next in Results and Discussion was developed on the basis of preliminary findings.

Optimization of the levels of extenders

In this experiment, different extenders such as rice flour, barnyard millet flour and texturized soy granule (in powder form) were incorporated separately into the basic formulation of dehydrated chicken meat rings (as standardized on the basis of preliminary trials), replacing the lean meat at 5 %, 10 % and 15 % level. Products were prepared from these extended formulations and studied for physico-chemical characteristics and sensory attributes. The optimum incorporation level of each extender was adjudged on the basis of physico-chemical characteristics and sensory attributes.

Analytical procedures

Physico-chemical analysis

Product yield and dehydration ratio

Weight of the batter prepared and the weight of the dried product after drying were recorded to calculate the product yield and dehydration ratio as follows.

Rehydration ratio

Weight of few dried rings was noted. These rings were rehydrated in 1:5 volumes of water at room temperature for 30 min. The rehydrated rings were weighed after mopping the excess water on surface by tissue paper and rehydration ratio was calculated as follows.

pH

Ten grams of sample (after grinding in the home mixer for 1 min.) was blended with 50 ml of distilled water for 1 min. using an Ultra Turrax tissue homogenizer (Model T25, Janke and Kenkel, IKA Labor Technik, Germany). The pH of the homogenate was recorded by immersing a combined glass electrode of a digital pH meter (Eutech Instruments, pH Tutor).

Water activity

Water activity was measured with the help of a water activity meter (Hygrolab 3, Rotronics, Switzerland). Ground sample was taken in the sample container of the water activity meter and introduced inside the meter, closed the upper lid and pressed the button. Reading was recorded in ‘quick mode’ and noted after the beep sound. It took 5–6 min to take one reading.

Lovibond tintometer colour units

The colour of the dehydrated chicken meat rings was measured using a Lovibond Tintometer (Model F, Greenwich, U.K.). Samples were finely ground in the home mixer, taken in the sample holder and secured against the viewing aperture. The sample colour was matched by adjusting the red (a) and yellow (b) units, while keeping the blue unit fixed at 0. The corresponding colour units were recorded. The hue and chroma values were determined using the formula, (tan−1)b/a (Little 1975) and (a2 + b2)½ (Froehlich et al.1983) respectively, where a = red unit and b = yellow unit.

Thiobarbituric acid reacting substances (TBARS) number

The TBARS number of samples was determined by using the distillation method described by Tarladgis et al. (1960). The optical density was recorded at 538 nm using spectrophotometer (Beckman, DU 640 spectrophotometer). The O.D. was multiplied by the factor 7.8 and TBARS value was expressed as mg malonaldehyde/kg of sample as suggested by Koniecko (1979).

Proximate composition

Moisture, crude fat, protein and ash contents of dehydrated chicken meat rings were determined by procedures prescribed by Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC 1995) using hot air oven, Soxhlet apparatus, Kjeldhal apparatus and Muffle furnace, respectively.

Lipid profile

Preparation of lipid extract

In the present investigation the method of Folch et al. (1957) was used for extracting lipids from dehydrated samples of the chicken meat rings. Five gram of sample was taken and ground using mortar and pestle with acid washed sand and transferred quantitatively into Erlenmeyer flask with 20 volumes of solvent mixture comprising of chloroform: methanol (2:1, v/v). The contents were allowed to stand at room temperature, with occasional stirring for 6 to 8 h. The extract was filtered through Whatman filter paper No. 1 and the residue was re-extracted with 10 more volumes (ml) of the same solvent mixture for 2 hours and filtered. The filtrates were combined and evaporated to dryness in vacuo at 55–60 °C in a rotary evaporator. The process of evaporation was repeated three times. For breaking the proteolipids, dried lipid residue was dissolved in one tenth volume of the original lipid extract in chloroform: methanol: water (64:32:4, v/v/v) and evaporated to dryness in vacuo at 55 °C. This step was repeated twice and the dried lipid residue was dissolved in 100 ml chloroform: methanol (2:1), v/v). The lipid extract was then washed with one-fifth volume of 0.9 % sodium chloride solution (mixing 20 ml of normal saline and shaking vigorously) in order to remove non-lipid impurities from the lipid sample. It was then allowed to stand overnight at room temperature. The chloroform layer was collected and evaporated to dryness in vacuo at 55–60 °C and repeated the process 3–4 times. Finally volume was made to 5 ml with chloroform. After adding a drop of 0.5 % butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT in chloroform), the lipid samples were stored in glass stoppered test tubes at −20 °C till further analysis.

Assay of total lipids

Total lipids of the samples were determined gravimetrically by the method described by Bligh and Dyer (1959). One ml of aliquot of the lipid extract was pipetted into dried stainless steelplanchets with constant predetermined weights. The samples were then dried at 60 °C in a hot air oven to a constant weight. Total lipids were expressed as mg/g of sample.

Assay of total phospholipids

Total phospholipids were estimated by determining the phosphorous content of the lipid extract by converting into inorganic phosphorous. Method described by Bartlett (1959) and modified by Marinetti (1962) was used for the estimation of the phospholipids phosphorous in the present study. Twenty-five μl lipid extract and standard phosphate solution (25, 50, 75 and 100 μ1) containing 0.4 mg/5 ml Potassium dihydrogen phosphate (the standard was prepared by dissolving 0.351 g Potassium dihydrogen phosphate in 10 ml 10 N H2SO4 and made the volume to 1 l) were digested with 1 ml of 60 % perchloric acid (for digestion, sample was heated at 60–65 °C over heating mantle and the digestion was indicated by colour changes gradually from black, brick and lastly colourless). Blank was prepared with perchloric acid (1 ml) only and treated in similar fashion. After digestion, colour was developed by heating in a boiling water bath for 7 min. after the addition of 7 ml distilled water, 0.5 ml of 2.5 % ammonium molybdate (25 g Ammonium molybdate was dissolved in 400 ml of distilled water and to it, 500 ml of 10 N H2SO4 was added and the volume was made up to 1 l with distilled water) and 0.2 ml of ANS reagent (The ANS reagent was prepared by dissolving 0.5 g 1- amino2-naphthol4-sulphonic acid in 200 ml of 15 % anhydrous sodium bisulphate, followed by the addition of 1.0 g of anhydrous sodium sulphite. The solution was allowed to stand overnight and filtered. The reagent is stable for 1 week when stored at 4 °C in brown bottle). The molybdenum blue formed was measured by reading the optical density at 830 nm in Beckman DU-40 Spectrophotometer. The phospholipid content was arrived at by multiplying the inorganic phosphorous content with the factor of 25 and expressed as mg per g of sample.

Assay of total cholesterol

In the present investigation, the Tschugaeff reaction as modified by Hanel and Dam (1955) was used for the estimation of total cholesterol because of its simplicity, quickness, sensitivity, reproducibility and equimolar colour yield for esterified and free cholesterol. Fifty μ1 of lipid extract and standard cholesterol solution (25, 50, 75 and 100 μ1) containing 1 mg in 1 ml chloroform were evaporated to dryness and dissolved in 2 ml of chloroform to which 1 ml of ZnCl2 reagent (reagent was prepared by dissolving 40 g of anhydrous zinc chloride in 153 ml of glacial acetic acid at 80 °C for two and a half hours and filtered through Whatman No.1 filter paper) and 1 ml of acetyl chloride were added and heated in a water bath at 60 °C for 10 min. Blank containing only 2 ml of chloroform and 1 ml of ZnCl2 and acetyl chloride was run at the same time. The colour complex formed was measured by reading the optical density at 528 nm in a spectrophotometer and expressed as mg per g of sample.

Micro-mineral estimation

Iron, cobalt, copper, zinc and manganese contents of dehydrated chicken meat rings were estimated by Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer [Electronics Corporation of India Ltd., Hyderabad, India, and Model No. 4141].

Sensory evaluation

Sensory evaluation of chicken meat rings was conducted using an eight point descriptive scale (Keeton 1983) with slight modifications, where 8 = excellent and 1 = extremely poor. The experienced panel consisting of scientists and post graduate students of the Division of Livestock Products Technology, IVRI, Izatnagar, evaluated the samples. The panelists were briefed with the nature of the experiments without disclosing the identity of the samples and were requested to rate them on an eight point descriptive scale on the sensory evaluation pro-forma for different attributes. Meat rings after rehydration and steam cooking were served to the panelists. Water was provided to rinse the mouth between tasting of each sample. The panelists evaluated the samples for attributes such as appearance, flavour, texture, meat flavor intensity, juiciness and overall acceptability.

Statistical analysis

Data generated from various trials under each experiment were pooled and compiled and analysed by using SAS (Statistical Analysis Software) (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA). Means and standard error were computed for each parameter. The data were subjected to analysis of variance, least significant difference and Tukey test for comparing the means.

Results and discussion

Standardization of the basic formulation and processing conditions for the preparation of dehydrated chicken meat rings from spent hen meat

The basic formulation for the preparation of dehydrated chicken meat rings was standardized as given following in Table 1. The product made from basic formulation was used as control for further comparisons with extended products.

Table 1.

Basic formulation for the preparation of dehydrated chicken meat rings

| Items in main mix | Quantity (%, by weight) |

|---|---|

| Chicken meat | 90.0 |

| Refined wheat flour | 7.0 |

| Potato starch | 3.0 |

| Other additives | Quantity (g/100 g of main mix) |

| Salt | 1.0 |

| Garlic | 2.0 |

| Kashmiri mirch powder | 0.7 |

| Spice mixture | 1.5 |

Sodium tri polyphosphates (0.3 g/100 g raw meat, used in meat cooking)

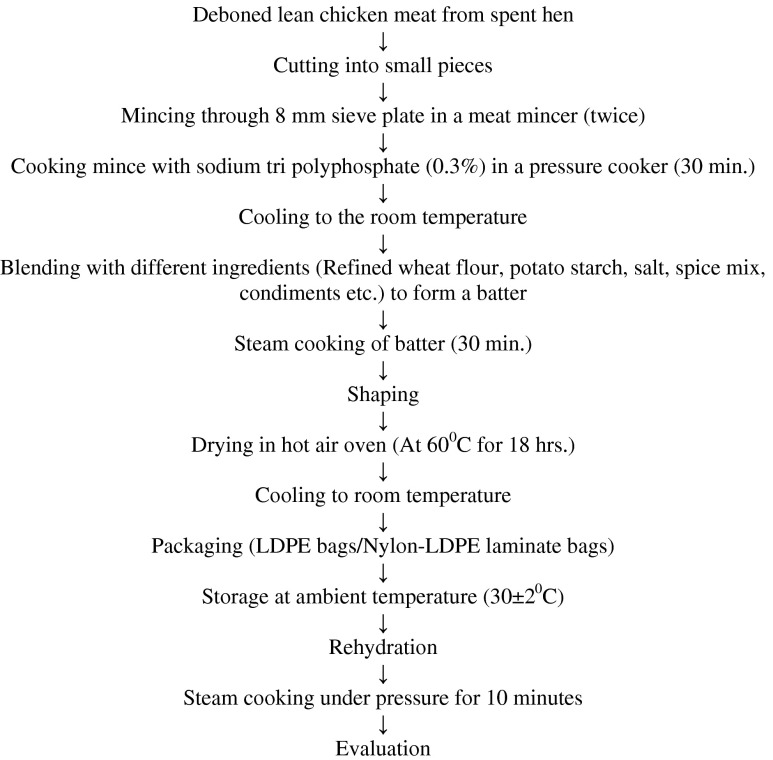

The processing method of dehydrated chicken meat rings was standardized as presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for preparation of dehydrated chicken meat rings

Optimization of the levels of various extenders

Different extenders such as rice flour (RF), barnyard millet flour (BMF) and texturized soy granule powder (TSGP) were incorporated into the basic formulation of dehydrated chicken meat rings standardized on the basis of preliminary trials, replacing the lean meat as indicated below Table 2.

Table 2.

Incorporation levels of different extenders used for the optimization of level

| Extenders | Control | Treatment | Treatment | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | ||

| Rice flour (1:1 hydration, w/w) | 0 | 5 % | 10 % | 15 % |

| Barnyard millet flour (1:1 hydration, w/w) | 0 | 5 % | 10 % | 15 % |

| Texturized soy granule powder (1:1 hydration, w/w) | 0 | 5 % | 10 % | 15 % |

The chicken meat rings prepared from the above extended formulations were analyzed for sensory characteristics and various physico-chemical analysis and on the basis of these, the optimum level of incorporation of extenders were adjudged separately as 10 % for RF, 10 % for BMF and 5 % for TSGP.

Quality evaluation of developed dehydrated chicken meat rings with various extenders at their optimum level of incorporation

Dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared from formulations extended with optimized levels of different extenders i.e.10 % rice flour, 10 % barnyard millet flour, and 5 % texturized soy granule powder were compared with each other as well as with control for physico-chemical and sensory characteristics.

Physico-chemical characteristics

Mean±SE values of yield percentage, dehydration ratio, rehydration ratio, pH, moisture percentage, fat percentage, protein percentage, ash percentage, and water activity of dehydrated chicken meat rings extended with optimum level of extenders viz., 10 % RF, 10 % BMF and 5 % TSGP are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Physico-chemical properties of dehydrated chicken meat rings extended with optimum levels of extenders (Mean±S.E)*

| Parameters | Control | RF 10 % | BMF 10 % | TSGP 5 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (%) | 39.66 ± 0.40b | 41.89 ± 0.32a | 41.83 ± 0.67a | 39.71 ± 0.61b |

| Dehydration ratio | 2.52 ± 0.03a | 2.39 ± 0.02b | 2.39 ± 0.04b | 2.52 ± 0.04a |

| Rehydration ratio | 1.62 ± 0.04ab | 1.58 ± 0.02b | 1.57 ± 0.04b | 1.74 ± 0.05a |

| PH | 6.18 ± 0.00b | 6.27 ± 0.02ab | 6.27 ± 0.03ab | 6.30 ± 0.03a |

| Moisture (%) | 7.51 ± 0.19a | 5.90 ± 0.31b | 7.21 ± 0.23a | 7.27 ± 0.18a |

| Fat (%) | 14.40 ± 0.37a | 10.28 ± 0.27c | 11.13 ± 0.28c | 12.66 ± 0.28b |

| Protein (%) | 47.76 ± 0.20b | 37.82 ± 0.22c | 36.14 ± 0.20d | 48.44 ± 0.26a |

| Ash (%) | 5.49 ± 0.08a | 4.15 ± 0.16b | 4.36 ± 0.06b | 5.70 ± 0.03a |

| Water activity | 0.53 ± 0.01a | 0.41 ± 0.02b | 0.47 ± 0.02ab | 0.47 ± 0.01a |

*Mean± S.E. with different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p < 0.05)

n = 6 for each treatment

Yield percentage of dehydrated chicken meat rings with optimum level of rice flour and barnyard millet flour were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than control but the yield of product with optimum level of TSGP was slightly higher than control, with no statistically significant difference (p > 0.05).It has been reported that the products prepared from spent hen have high cooking loss due to high fat content and poor water binding capacity (Acton and Dick 1978 and Buyck et al.1982). Hence, with the incorporation of extender into mix replacing equal quantity of meat, yield of product might have increased. Yield of the product with 5 % TSGP was lower than other treatments, which might be due to lower level of replacement of lean meat.

Dehydration ratio of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF had significantly lower (p < 0.05) value than control. Product with 5 % TSGP had almost equal value as of control but had significantly higher (p < 0.05) value than the products with optimum level of RF and BMF. Rehydration ratio for product with optimum level of texturized soy granule powder was comparable to control but significantly higher (p < 0.05) than product with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF. Rehydration ratio for dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF were comparable to each other as well as to control also. A relation between dehydration ratio and rehydration ratio was observed as the rehydration ratio of the product was increasing to a certain extent with increase in dehydration ratio and it is in agreement with the results of Uprit and Mishra (2003).

pH values for dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum levels of TSGP was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than control but there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) among the three treatments. The higher pH value of products with extenders might probably be due to the higher pH values of extenders used in the formulation itself.

Moisture content was highest for control (7.51 ± 0.19 %) and lowest for product with optimum level of RF (5.90 ±0.31 %). Moisture content of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of RF was significantly (p < 0.05) lower than the control, and other two treatment products. No significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed among other products.

Fat content of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF, BMF and TSGP were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control. Product with optimum level of TSGP had significantly lower (p < 0.05) value than control but had significantly higher (p < 0.05) value for fat percentage than products with optimum level of RF and BMF. The lower level of fat in treatments might probably be due to lower level of chicken meat in treatments as compared to the control. Berwal et al. (1996) and Lee et al. (2003) reported a higher fat content in Turkey meat papads and popped cereal snacks containing chicken meat respectively.

Protein percentage of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of TSGP was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than control as well as from products with optimum level of RF and BMF. Protein percentage of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF were significantly (P < 0.05) lower than control. Protein percentage of the product with optimum level of BMF had significantly (P < 0.05) lower value than other treated products. The higher protein content in dehydrated chicken meat rings with optimum level of TSGP could be due to the contribution of high protein TSGP in the product and lower level of replacement of lean meat.

Ash percentage of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control. Product with optimum level of TSGP had non significantly higher (P > 0.05) value than control but had significantly higher (p < 0.05) value for ash percentage than the products with optimum level of RF and BMF.

Water activity of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control but value of aw for products with optimum level of BMF and TSGP were comparable with control. Water activity of product with optimum level of TSGP was significantly (p < 0.05) higher than the product with optimum level of RF, however aw value for product with optimum level of BMF was comparable to other two treatments. Also, the higher water activity of control was reflected in the higher moisture content and lower water activity of RF product in the lower moisture content. The results are in agreement with that of Thomas (2007), who observed a lowered water activity with lowering of moisture content. According to Lewicki (2004) and Rahman and Labuza (2007), lowering of water content resulted in lowered water activity, but both were not directly proportional.

Colour characteristics

Colour parameters like redness and yellowness were measured and hue and chroma values were calculated. Mean ± SE values of the above parameters are presented in Table 4. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in the redness value between control and treatments as well as among the treatments. The highest (2.20 ± 0.03) and the lowest (2.12 ± 0.02) value were observed in control product and the product with optimum level of BMF. The values of redness in treatments observed to be on lower side than the control might probably be due to the lower level of meat in them when compared to control. This agrees to the findings of Chand (2011) who reported a significant increase in redness and yellowness values in chicken snacks when compared to control snacks with no meat. Thomas (2007) also reported a decrease in redness values in pork sausages as the percentage of lean meat decreased and fat level increased.

Table 4.

Colour values of dehydrated chicken meat rings extended with optimum levels of extenders (Mean±S.E)*

| Parameters | Control | RF10% | BMF 10 % | TSGP 5 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Redness | 2.20 ± 0.03 | 2.15 ± 0.02 | 2.12 ± 0.02 | 2.17 ± 0.07 |

| Yellowness | 5.48 ± 0.03a | 5.43 ± 0.04a | 5.42 ± 0.05a | 4.58 ± 0.25b |

| Hue | 68.13 ± 0.30a | 68.40 ± 0.29a | 68.64 ± 0.28a | 64.56 ± 0.62b |

| Chroma | 5.91 ± 0.03a | 5.84 ± 0.04a | 5.82 ± 0.04a | 5.07 ± 0.25b |

*Mean± S.E. with different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p < 0.05)

n = 6 for each treatment

Yellowness value of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of TSGP was significantly lower (P < 0.05) than control. Product with optimum level of RF and BMF had non significantly lower (p > 0.05) yellowness value than control but had significantly higher (p < 0.05) value than product with optimum level of TSGP. Hue value for product with optimum level of TSGP was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control as well as to other treatments.

Hue value for dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF were non significantly higher (p > 0.05) than control. Hue value was highest for dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of BMF (68.19 ± 0.66) and lowest for products with optimum level of TSGP (64.56 ± 0.62).

Chroma values ranged from 5.07 ± 0.25 in meat rings with optimum level of incorporation of TSGP to 5.91 ± 0.03 in control. Chroma value for products with optimum level of TSGP was significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control as well as to other treatments. Chroma value for dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF and BMF were non significantly lower (p > 0.05) than control.

Lipid profile

The lipid composition of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with selected levels of extenders viz.,10 % rice flour,10 % barnyard millet flour and 5 % texturized soy granule powder and control are presented in Table 5. Total lipid content (mg/g) of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of RF, BMF and TSGP were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control. The lower level of total lipid content in treatments might probably be due to lower level of chicken meat in treatments as compared to the control. Product with optimum level of RF had significantly lower (p < 0.05) total lipid content than the product with optimum level of TSGP and BMF. The total lipid content was comparable in products with BMF and TSGP incorporation, however product with optimum level of BMF had significantly higher (p < 0.05) value than product with optimum level of RF. It might be due to higher fat content in barnyard millet flour. The fat content in BMF with varietal differences ranges between 3.20 and 9.84 % (Veena et al.2005).

Table 5.

Lipid profile of dehydrated chicken meat rings extended with optimum levels of extenders (Mean±S.E)

| Parameters | Control | RF 10 % | BMF 10 % | TSGP 5 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total lipids (mg/g) | 127.58 ± 0.9a | 102.50 ± 1.12c | 108.08 ± 0.60b | 106.37 ± 0.65b |

| Cholesterol (mg/g) | 3.25 ± 0.06a | 2.83 ± 0.07c | 2.96 ± 0.09bc | 3.15 ± 0.07ab |

| Phospholipids (mg/g) | 18.48 ± 0.149a | 15.145 ± 0.036c | 16.38 ± 0.10b | 15.27 ± 0.12c |

*Mean± S.E. with different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p < 0.05)

n = 6 for each treatment

The total cholesterol content (mg/g) for products with optimum level of RF and BMF were significantly lower (p < 0.05) than control. The total cholesterol content was comparable in products with optimum level of RF and BMF as well as in products with optimum level of TSGP and BMF. The cholesterol content for products with optimum level of TSGP was comparable with control but was significantly higher (p < 0.05) than products with optimum level of RF.

The phospholipid content (mg/g) of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with optimum level of incorporation of extenders were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than control. Product with optimum level of BMF had significantly lower (p < 0.05) phospholipid content than control but significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the product with optimum level of RF and TSGP. The phospholipid content was comparable in products with optimum level of RF and TSGP.

Mineral profile

The mineral composition of dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with selected levels of extenders viz.,10 % rice flour,10 % barnyard millet flour and 5 % texturized soy granule powder and control are presented in Table 6. The zinc content in the product with optimum level of RF and BMF were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than control whereas product with optimum level of TSGP had significantly (p < 0.05) higher value than control. Copper content in all the treated products were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than control. Among treatments, copper value was comparable between product with optimum level of BMF and TSGP. Copper content in product with optimum level of RF had significantly (p < 0.05) lower value than the other treated products. Manganese content was lowest in product with optimum level of TSGP (12.89 ± 0.05) and highest in product with optimum level of BMF (16.45 ± 0.05). Products with optimum level of BMF and RF had significantly (p < 0.05) higher value than control whereas products with optimum level of TSGP had significantly (p < 0.05) lower value than control. Cobalt content in products with optimum level of RF and BMF were significantly (p < 0.05) lower than control whereas product with optimum level of TSGP had significantly (p < 0.05) higher value than control. Among treatments, products with optimum level of TSGP had significantly (p < 0.05) higher value than the other treated products whereas the value was comparable between products with optimum level of RF and BMF. High variability in the results could be due to variation in the muscles being used for different formulations. Marchello et al. (1985) also reported that mineral content varies from muscle to muscle. Iron content was lowest in product with optimum level of RF (49.42 ± 0.16) and highest in product with optimum level of BMF (664.48 ± 4.76). Iron content in products with optimum level of TSGP and BMF were significantly higher (p < 0.05) than control whereas, it was lowest at products with optimum level of RF.

Table 6.

Mineral profile of dehydrated chicken meat rings extended with optimum levels of extenders (Mean± S.E)

| Parameters | Control | RF 10 % | BMF 10 % | TSGP 5 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron (ppm) | 62.97 ± 0.30c | 49.42 ± 0.16d | 664.48 ± 4.76a | 89.07 ± 0.30b |

| Copper (ppm) | 7.72 ± 0.08a | 6.82 ± 0.06c | 7.36 ± 0.13b | 7.37 ± 0.11b |

| Zinc (ppm) | 29.05 ± 0.16b | 26.44 ± 0.12d | 27.53 ± 0.16c | 29.89 ± 0.20a |

| Manganese (ppm) | 13.34 ± 0.07c | 13.88 ± 0.08b | 16.45 ± 0.05a | 12.89 ± 0.05d |

| Cobalt (ppm) | 45.20 ± 0.21b | 41.69 ± 0.27c | 42.23 ± 0.45c | 47.46 ± 0.37a |

*Mean± S.E. with different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p < 0.05)

n = 6 for each treatment

In the present study, higher value of minerals and high variability could be due to the reason that no specific meat cut was used. Further, the spices and condiments used in the formulation of product may contain traces of minerals.

Sensory characteristics

Sensory attributes like appearance (of dried and cooked products), flavour, texture, meat flavour intensity, juiciness and overall acceptability were evaluated after rehydration and cooking. Mean ± SE values of the above attributes are presented in Table 7. No significant difference (p > 0.05) was observed in the appearance scores of treatments both in dried and rehydrated and cooked forms. Further, the appearance score of control was not significantly (P > 0.05) different from the treated products. Flavour scores for treatments as well as control were comparable among themselves. Texture scores of all the three treatments did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) with control and also, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) among treatments. The non significant difference (p > 0.05) in texture scores might be due to the different extender mixes. Modi and Prakash (2008) prepared extended dehydrated meat cubes using different extenders and observed that carrot and potato decreased firmness, while sorghum, wheat flour and semolina considerably increased firmness of the product.

Table 7.

Sensory attributes of dehydrated chicken meat rings extended with optimum levels of extenders (Mean± S.E)*

| Attributes | Control | RF 10 % | BMF 10 % | TSGP 5 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance (dried product) | 6.97 ± 0.07 | 6.93 ± 0.03 | 6.92 ± 0.07 | 6.91 ± 0.07 |

| Appearance (cooked product) | 6.86 ± 0.06 | 6.86 ± 0.04 | 6.83 ± 0.05 | 6.83 ± 0.05 |

| Flavour | 6.83 ± 0.07 | 6.66 ± 0.09 | 6.60 ± 0.12 | 6.75 ± 0.10 |

| Texture | 6.84 ± 0.10 | 6.78 ± 0.11 | 6.61 ± 0.09 | 6.74 ± 0.13 |

| Meat flavour intensity | 6.87 ± 0.08a | 6.76 ± 0.07ab | 6.48 ± 0.12b | 6.51 ± 0.10b |

| Juiciness | 6.65 ± 0.09 | 6.56 ± 0.09 | 6.49 ± 0.10 | 6.57 ± 0.09 |

| Overall acceptability | 6.74 ± 0.09 | 6.70 ± 0.07 | 6.46 ± 0.11 | 6.57 ± 0.09 |

*Mean± S.E. with different superscripts in a row differ significantly (p < 0.05)

n = 22 for each treatment

Meat flavour intensity scores for products with optimum level of TSGP and BMF were significantly (P < 0.05) lower than control however meat flavour intensity score for product with optimum level of RF was comparable with control. The meat flavour intensity scores were comparable among all treatments. The lower meat flavour intensity score for treated products might probably be due to lower level of meat in them. This is in accordance with the findings of Sharma and Nanda (2002) who had reported an increasing intensity of meat flavour in chicken chips with increase in level of meat.

Juiciness scores of all treatments did not differ significantly (p > 0.05) with control and also there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) among treatments, however, treated products had non significantly (p > 0.05) lower score for juiciness than control. This may be the effect of extenders used. Modi et al. (2007) reported that juiciness of chicken kebabs prepared from dehydrated mix was affected by the level of starch, milk powder and the interaction between the two. Modi and Prakash (2008) reported that pearl millet and cabbage resulted in an increased juiciness of extended and dehydrated meat cubes, after rehydration, whereas maize flour had the reverse effect.

Overall acceptability scores were not significantly different (p > 0.05) among the treatments, however, products with optimum level of incorporation of RF had the highest score (6.70 ± 0.07) and products with optimum level of incorporation of BMF, the lowest (6.46 ± 0.11). The overall acceptability scores of control and dehydrated chicken meat rings prepared with different extenders did not differ significantly (p > 0.05).

Conclusions

This study explored that spent hen meat can be utilized for the preparation of good quality dehydrated chicken meat rings, which can be consumed after rehydration and cooking. The product can be prepared by utilizing spent hen meat at 90 % level, potato starch at 3 % and refined wheat flour at 7 % level along with standardized amount of spices, condiments, common salt and STPP. Further, addition of different extenders such as rice flour, barnyard millet flour and TSGP can be done separately at optimum levels of 10 %, 10 % and 5 % respectively replacing lean meat in the formulation. In sensory evaluation, the extended products showed good to very good acceptability. As per the sensory evaluation scores, rice flour was found to be the best among the three extenders studied. The products with 10 % RF was estimated to have a product yield of 41.89 % and it had 10.28 % fat and 37.82 % protein in it. It is concluded that spent hen meat which is considered as low economic value product may be used for the production of value added products of dehydrated type which have good sensory acceptability along with shelf stability.

References

- Acton JC, Dick RL. Effect of skin content on some properties of poultry loaves. Poult Sci. 1978;57(5):1255–1259. doi: 10.3382/ps.0571255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. 16. Virginia: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett GR. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwal JS, Dhanda JS, Berwal RK. Studies on rice and turkey meat blend Papads. J Food Sci Technol. 1996;33:237–239. [Google Scholar]

- Bligh E, Dyer W. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buyck MJ, Seideman SC, Quenzer NM, Donnelly LS. Physical and sensory properties of chicken skin patties made with various levels of fat and skin. J Food Protect. 1982;45:214–217. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-45.3.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand S (2011) Development of shelf stable ready-to-fry/microwavable chicken meat based snacks. M.V.Sc. Thesis submitted to Deemed University, IVRI, Izatnagar, UP, India

- FAO (2009) Food and Agricultural organization. Database available from www.fao.org

- Folch J, Less M, Saloane-stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich DA, Gullet EA, Usborne WR. Effect of nitrite and salt on the colour, flavour and overall acceptability of ham. J Food Sci. 1983;48:152–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1983.tb14811.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanel HK, Dam H. Determination of small amounts of total cholesterol by Tschugaeff reaction with a note on the determination of lanosterol. Acta Chem Scand. 1955;9:677–682. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.09-0677. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jay JM, Loessner MJ and Golden DA (2005) Modern food microbiology, 7th ed. Springer (India) Private Limited pp 443–447

- Keeton JT (1983) Effect of fat and NaC1/posphate levels on the chemical and sensory properties of pork patties. J Food Sci 48:879–881

- Koniecko EK (1979) In: Handbook for Meat Chemists. A very Publishing Group Inc., Wayne, New Jersey, USA, pp 51–52, 68–69

- Lee SO, Min JS, Kim IS, Lee M. Physical evaluation of popped cereal snacks with spent hen meat. Meat Sci. 2003;64:383–390. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(02)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewicki PP (2004) Drying. In: Encyclopaedia of Meat Sciences, Vol-1. Jensen WK, Devine C and Dikeman M. (eds). Elsevier Ltd. pp 402–411

- Little AC (1975) Off on a tangent. J Food Sci 40:410–412

- Marchello MJ, Slanger WD, Miline DB (1985) Macro and micro minerals from selected muscles of pork. J Food Sci 50:1375–1378

- Marinetti GV. Chromatographic separation, identification and analysis of phosphatides. J. Lipid Res. 1962;3:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Modi VK, Prakash M. Quick and reliable screening of compatible ingredients for the formulation of extended meat cubes using Plackett-Burman design. Lebensm-Wiss.u Technol. 2008;41:878–882. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modi VK, Sachindra NM, Nagegowda P, Mahendrakar NS, Rao DN. Quality changes during the storage of dehydrated chicken kebab mix. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2007;42:827–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01291.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman MS and Labuza TP (2007) Water activity and food preservation. In:Handbook of Food Preservation, 2nd ed. Rahman MS (ed.). Taylor and Francis group. pp 447–476

- Sharma BD, Nanda PK. Studies on the development and storage stability of chicken chips. Indian J Poult Sc. 2002;37:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp JG (1953) Dehydrated meat. Food Invest. Board Spec. Rept. 57, HM Stationery Office, London

- Tarladgis BG, Watts BM, Younathan MT, Dugan LR. A distillation method for the quantitative determination of malonaldehyde in rancid foods. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1960;37:403–406. doi: 10.1007/BF02630824. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R (2007) Development of shelf stable pork sausages using hurdle technology. Ph.D. Thesis submitted to the Deemed University, IVRI, Izatnagar, UP, India

- Uprit S, Mishra HN. Microwave convective drying and storage of soy-fortified paneer. Trans I Chem E. 2003;81:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- Vadivambal R, Jayas DS. Changes in quality of micro wave- treated agricultural products- a review. Biosystems Eng. 2007;98:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2007.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Veena B, Chimmad BV, Naik RK, Shantakumar G. Physico-chemical and nutritional studies in barnyard millet. Karnataka J Agril Sci. 2005;18:101–105. [Google Scholar]