Abstract

Flavonoids (FGs) are a large group of polyphenolic compounds with low molecular weight, found in free and glycozidic forms in plants. Citrus fruits can be used as a food supplement containing hesperidin and flavonoids to prevent infections and boost the immune system in human body. The aim of this study was the investigation of the effect of clove oil and storage period on the amount of hesperidin and naringin component in orange peel (cv. Valencia). Four treatments including clove oil (1 %), wax, mixture of wax-clove oil, control and storage period were applied. Treated fruits were stored at 7 °C and 85 % relative humidity for 3 months and naringin, hesperidin, antioxidant activity, total pheenolic compounds, TSS, Vitamin C, fruits weight loss, pH, acidity and carbohydrates content were measured every 3 weeks. The amount of hesperidin and naringin was determined using high performance liquid chromatography at the detection wavelength of 285 nm. Antioxidant activity was measured using the 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl-hydrate (DPPH) free radical scavenging assay. Total phenolic compounds were measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu micro method. Results showed that naringin and hesperidin were decreased during storage. Different treatment only had significant effect on the amount of hesperidin while storage period affected both of narigin and hesperidin. Results of correlation study, indicated strong relation between antioxidant activity and amount of naringin and hesperidin during storage time. However, at the end of storage period, the amount of hesperidin and naringin were diminished independent of different covers. Probably anaerobic condition caused such reduction. Results showed that the amount of TSS, fruit hardness, weight loss, total sugar and fructose content were increased during storage period while total acidity, pH and glucose content showed descending trend during storage periods. In conclusion, hesperidin and naringin of peels can be used as suitable quality indexes indicating proper conditions for storage.

Keywords: Citrus fruits, Phenolic compounds, Antioxidant, Quality attributes

Introduction

Citrus fruits are important because of their nutritional and antioxidant properties. According to their molecular structures, flavonoids are divided into six classes: flavones, flavanones, flavonols, isoflavones, anthocyanidins and flavanols (or catechins) (Peterson and Dwyer 1998). Flavonoids identified in Citrus fruits cover more than 60 types, according to the five classes mentioned (Horowitz and Gentili 1977): flavones, flavanones, flavonols, flavans and anthocyanins (the last only in blood oranges). Citrus flavanones are present in the glycoside or aglycone forms. Among the aglycone forms, naringin and hesperidin are the most important flavanones (Gil-Izquierdo et al. 2001). Flavonoids and phenolic compounds have many biological properties, including hepatoprotective, antibacterial and anticancer activities (Tiwari 2001). Moreover, citrus flavonoids, particularly hesperidin, has revealed a wide range of therapeutic properties in medical and clinical applications such as antihypertensive, diuretic, analgesic and hypolipidemic activities (Galati et al. 1994; Monforte et al. 1995). The amounts of bioactive compounds in fruit, including citrus flavonoids, are a function of geographical region, climate, soil conditions, type of cultivar, growing season, harvest date, storage, low-dose irradiation, and other conditions (Patil et al. 2004). Recently, this fruit has been reported to have anti-allergic activity (Fujita et al. 2008) antioxidant effects (Shin et al. 2006), and several studies have been carried out to characterize the flavonoid components in the edible tissue of C. unshiu Marc. (Sentandreu et al. 2007; Yoo et al. 2009). The Citrus peel and seeds are very rich in phenolic compounds, such as phenolic acids and flavonoids. The peels are richer in flavonoids than the seeds (Yousof et al. 1999). Since a Citrus fruit is peeled, peel and seeds are not used. It is necessary to estimate these by-products as natural antioxidants in foods (Kroyer 1986). Generally Valencia orange after harvest is preceded by using edible waxes following storage. There was no report on antioxidant, narigin and hesperidin contents after application of such treatments. Antimicrobial properties of essential oils from various plant species have been proved to affect and arrest fungal development in vitro and in vivo in various horticultural commodities. The aim of this study was to determine hesperidin and naringin, antioxidant capacity and Vitamin C of Valencia orange during storage as covered by different compounds. Further comparison of two covers of wax and essential oils in order to preserve Valencia orange quality was another objective.

Materials and methods

In this study more than 200 Valencia orange fruits from a commercial orchard located in Ghaemshahr city of Iran, south of Caspian Sea were collected. Clove oil, which dissolved in alcohol 25 % and 1 % concentration, was used. This project was conducted in four treatments. Control treatments, Waxes, oils, mixture of wax-oil and fruits treated were stored for 3 months at a temperature of 7° C and 80–85 relative percent humidity.

Clove oil

Clove oil is obtained by distillation of the flowers, stems and leaves of the clove tree (Eugenia aromatica or Eugenia caryophyllata, Fam. Myrtaceae) (Anderson et al. 1997; Mylonasa et al. 2005). Eugenol (4-allyl-2-methoxyphenol), the active substance, makes up 90–95 % of the clove oil (Briozzo et al. 1989), and as a food additive is classified by the FDA to be a substance that is generally regarded as safe (Anderson et al. 1997).

Sample preparation

The orange peel samples were dried in an oven at 35 °C, and powdered by an domestic mill. In the next step, to prepare the extract, 1 g of powdered bark was mixed with 10 ml methanol and stirred with magnetic stirring for 20 min. The extract was filtered again through filter paper (Whatman 40) and reached to volume of 10 ml. The sample was diluted 20 times with methanol. For preparation of naringin and hesperidin .standard solution initially 10 mg of 95 % naringin and hesperidine poured into 100 ml balloon and 2 mL of Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution was added and volume loaded to 100 ml using methanol. The standard solutions with a concentration of 100 mg/ml of naringin and hesperidin were obtained.

Naringin and hesperidin measurement in peel

The contents of Flavonoids (naringin and hesperidin) were determined by use of HPLC method. For this purpose 10 μl of extract was injected into a HPLC system, and it was filtered through a millipore membrane (0.22 μm) before injection. The analysis utilized a Diamonsil C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm) using aceto nitril: water: acetic acid (37:75:5) (v/v/v) as the mobile phase at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min at 40 °C oven temperature, they were monitored at 283 nm for quantification of FGs. Identification of the FGs was accomplished by comparing the retention times of peaks in samples to those of FG standards. Calculation of FGs concentration (expressed as mg/L) was carried out by an external standard method using calibration curves. Samples were filtered through a 0.45- μm pore size membrane filter before injection.

Antioxidant activity of juice

The ability of extracts to scavenge DPPH radicals was determined according to the method Blois (1958). Briefly, 1 ml of a 1 mM methanolic solution of DPPH was mixed with 3 ml of extract solution in methanol (containing 50–400 μg of dried extract). The mixture was then homogenized vigorously and left for 30 min in the dark place (at room temperature). Its absorbance was measured at 517 nm and activity was expressed as percentage of DPPH scavenging relative to control using the following equation:

| 1 |

Estimation of total phenolic compounds

Total phenolic content of each extract was determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu micro method (Slinkard, and Singleton 1977). Briefly, 20 μl of extract solution were mixed with 300 μl of Na2CO3 solution (20 %), then 1.16 ml of distilled water and 100 μl of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent added to mixture after 1 min and 8 min respectively. Subsequently, the mixture was incubated in a shaking incubator at 40 °C for 30 min and its absorbance was measured at 760 nm. Gallic acid was used as a standard for calibration curve. The phenolic content was expressed as gallic acid equivalents by using the following linear equation

| 2 |

Where A is the absorbance and C is concentration as gallic acid equivalents (μg/ml).

Fruits hardness and weight loss

Fruits hardness (kg/cm2) was measured with penitrometer (F-T 327).

Fruits weight loss in each storage periods was calculated from Eq. 3 as bellow:

| 3 |

Where w1 is initial weight of fruit at time 0 and w2 is fruit weight at each storage time.

The pH of fruits was measured with the digital pH meter (GF-300) and total acidity was measured by titration method.

Ascorbic acid (mg/100 ml of juice)

Ascorbic acid was determined by the indophenol’s Titration method used by AOAC (2005).

Total soluble solids (Brix)

Total soluble solids were determined according to AOAC (2005) using hand refrectometer at room temperature.

Extraction and measurement of soluble sugars (total sugar, glucose, fructose and sucrose) content

Soluble sugars were extracted according to Omokolo et al. (1996) method and the produced extract was used for sugar analysis. Total sugar, glucose and fructose content (reducing sugar) and sucrose (non reducing sugar) content were measured by McCready et al. (1950), Ashwell (1957), Miller (1959) and Handel (1968) methods respectively.

Results and discussion

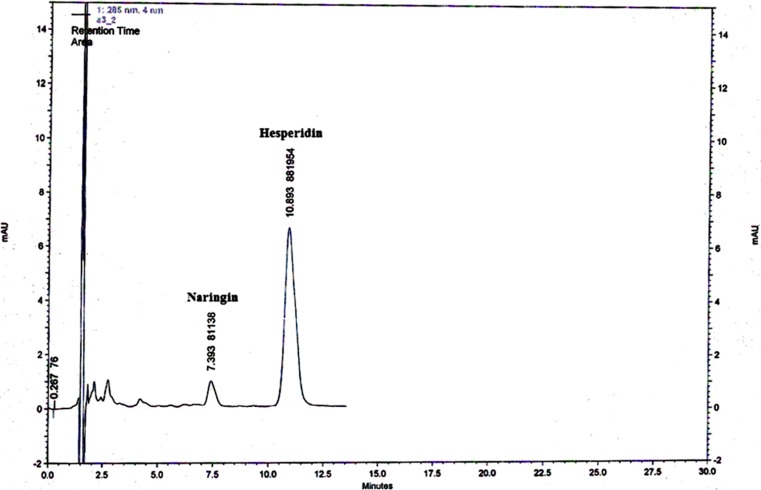

The retention time (RT) of naringin (7.39 min) and hesperidin (10.89 min) was showed in Fig. 1. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) for hesperidin and naringin showed that period of storage had significant effect on these components. But cover types affected only hesperidin while interaction of storage period and cover type had no significant effect on these two components (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

HPLC chromatogram of the naringin and hesperidin from the peel of Valencia orange

Table 1.

ANOVA of flavonoids and quality attributes of Valencia orange as a function of storage time and coating type

| Surce of variation | df | Hesperidin (ppm) | Naringin (ppm) | TSS (%) | Vitamin C (mg/100gr) | DPPH (%) | Total phenolic compounds (mg galic acid/100gr) | Weight loss (%) | Hardness (kg/cm2) | pH | Acidity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of cover | 3 | 531144.09a | 114882.14 ns | 0.6144ns | 7.057ns | 30.285b | 322.388ns | 14.14ns | 11.0127b | 0.0114ns | 0.005ns |

| Time | 4 | 1625926.05b | 66766.3a | 9.405b | 262.882b | 284.296b | 21369.073b | 17.33b | 7.4117b | 0.8747b | 0.1224b |

| Type of cover × time | 9 | 218715.51 ns | 6330.8 ns | 1.580ns | 9.154ns | 11.601b | 501.827a | 8.186ns | 1.2294a | 0.0524a | 0.007ns |

Superscripts ns, a and bmeans not significant, significant at 0.05 and 0.01 level respectively

Naringin value in fruit peel during storage period reduced dramatically. At the beginning time of storage period naringin value was 390.60 ppm while at the end of storage; it was reached 30.33 ppm (Fig. 2). Hesperidin exposed a trend of increase until 6 weeks after initial spot of the experiment. As it is indicated (Fig. 3), the value of hesperidin increased from 1158.5 ppm in the first week of experiment to level of 1,561 ppm after 6 weeks storage. At the end of storage period the level of hesperidin reduced prominently and reached to level of 557 ppm and 51.8 % reduction of hesperidin was observed during trend of storage period.

Fig. 2.

The variation of naringin content of peel as a function of coating type and storage time

Fig. 3.

The variation of hesperidin content of peel as a function of coating type and storage time

Results extracted from analysis of variance (Table 1) indicated that type of fruit cover had no influence on amount of moisture loss. However storage period had impressive effect on moisture reduction of fruit peel. In the end of first 3 weeks of storage the rate of moisture loss was 0.92 % of total fruit weight. While in the end of week nine the rate of moisture reduction was 4.72 % of fruit weight. The trend of moisture reduction was an exponential type. At the end of the experiment, the moisture reduction met a level of 8.46 % of total fruit weight (Fig. 4). Fifty percent of moisture loss was occurred at the end of ninth week of storage. Another 50 % of moisture loss was detected at the end of storage period. The recent result showed that from week nine of storage the trend of moisture loss was more accelerative in comparison with the earlier periods.

Fig. 4.

Valencia orange weight loss (%) during storage

In orange fruit the predominant form of Vitamin C is ascorbic acid while dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) is less than 10 % of total vitamin C (Lee and Kader 2000). Results showed that vitamin C had an increasing trend until day of 42 of storage, as this result was similar to hesperidin. However after 42 days storage the vitamin C content indicated a diminishing tendency (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Variation in vitamin C content of Valencia orange juice during storage

Antioxidant activity of juice

With respect to the analysis of variance (Table, 1), applied treatments fruit cover, period of storage and their interactions had significant effect on the concentration of antioxidant (P ≤ 0.05). In general antioxidant indicated a reducing style for all the employed treatments. With increasing period of storage the clove oil cover showed the highest antioxidant activity, 41.96 % (Fig. 6.) The lowest activity of antioxidant was observed for application of wax individually.

Fig. 6.

Variation of antioxidant activity (measured by DPPH assay) in Valencia orange during storage

During storage period (84 days) no decay were observed. In coated samples with mixture of clove oil- wax and essential oils treatments while decay was occurred in blank and treated samples with wax after 6 weeks of storage.

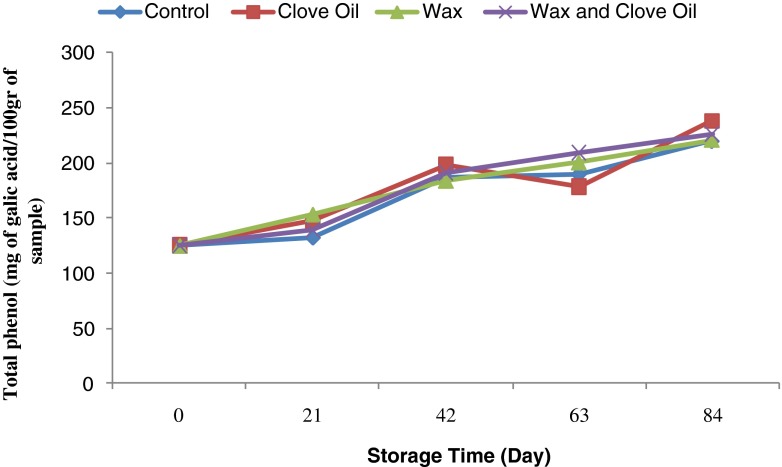

With respect to the analysis of variance (Table 1), applied treatments period of storage and it interaction with fruit cover had significant effect on the total phenolic compounds (P ≤ 0.05).

According to the Fig. 7, during storage period the amount of total phenol compound increased contrary to the trend of antioxidant activity. As it can be seen the total phenol content was equal to 125.04 and 226.40 mg/100 g Gallic acid at the beginning and the end of storage periods respectively. It should be noted that there was no significant difference between the applied coatings in respect to total phenol content (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Variation in total phenol content of Valencia orange during storage

Reduction of the amount of total phenols during storage period depends on the storage conditions. The anthocyanin content in the blood Orange fruit is usually increased in the storage periods. Paolo and Marisol (2008) indicated that the amount of anthocyanin, flaonons increased during storage while the amount of vitamin c reduced. Therefore, increase in antioxidant activity of blood orange fruits during storage period, may be due to synthesis of phenolic compounds including anthocyanin. Increase anthocyanin content in Blood orange fruit during storage is related to the fruit varieties. Total phenol content of control and coated orange samples was reduced during storage period which is in agreement with the result of Lim et al. (2006) study on mango fruit. Decrease in total phenols content during storage can be related to the oxidative activity of polyphenol oxidase (P.P.O) enzyme that makes phenol to quinones compound (Kays 1997). Escarpa and Gonzahez (2001) reported that total phenols reduction influenced by storage time and temperature. They reported the reduction of 10–20 % total phenol content of orange juice after 6 months storage in low temperature condition.

Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is the major antioxidant compound found in citrus fruits juice (Gardner et al. 2000). Vitamin C retention has been applied as a quality indicator during shelf-life of citrus-derived products (Lee and Coates 1999). During storage the vitamin C content of the orange diminished significantly (P < 0.05) in both waxed and unwaxed samples. The loss in vitamin C during storage was in accordance with the report of Evensen (1983) and Albuquerque et al. (2005). The observed effect of storage time on vitamin C degradation could be explained due to indirect degradation through polyphenol Oxidase, cytochrome oxidase and peroxidase activity (Lee and Kader 2000). With the passage of time deterioration of ascorbic acid lead to more TSS. This is because structural formula of ascorbic acid is similar to glucose therefore reduction in ascorbic acid led to increase of glucose and higher TSS (Fig. 8) )Manzano and Diaz 2001). Ascorbic acid is susceptible to oxidative deterioration as well as mild oxidation of ascorbic acid results in the formation of dehydroascorbic acid. The presence of oxygen accelerates oxidation process in fruits (Ahmad et al. 1997). Our results were in line with findings of Kumar et al. (2000): they found that ascorbic acid decreased with increasing period of storage in fruits of Kinnow. According to (Shahid and Abbasi 2011) that the Vitamin C content of fresh fruit was maximum just before ripening and then decreases due to the action of enzymes called ascorbic acid oxidase. Usually much of the ascorbic acid is transferred to juice and oxidized. The results congregate with the finding of Verma and Dashora (2000) who narrated that when storage period proceeded, TSS increased while ascorbic acid and acidity of Kagzi lime fruits decreased.

Fig. 8.

Total soluble solid variation in Valencia orange during storage

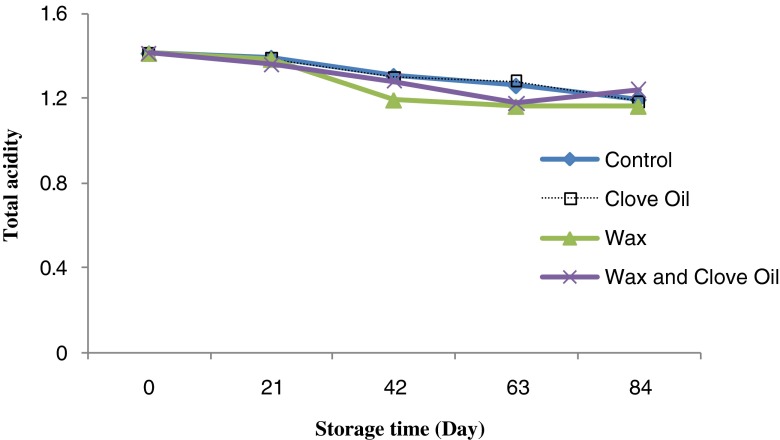

According to the analysis of variance (Table 1), storage period had significant effect on TSS, pH and total acidity of fruit while type of cover had no significant effect on these quality attributes. Edible covers and storage time had significant effect on the fruit pH during storage period (p < 0.05).

Results showed that the amount of TSS was increased during storage period from 10.08 0BX (at the first day of storage) to 12.35 0BX after 3 months of storage; it is noteworthy that the amount of total soluble solids from the ninth week of storage showed a negligible reduction. As was mentioned the cover type had no significant effect on the amount of TSS during storage period (Fig. 8).

Results showed that in Valencia orange fruit, total acidity showed descending trend during storage periods, from 1.41 % to 1.19 % at the beginning to the end of the storage period. There was no significant difference between different treatments in term of total acidity value (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9.

Effect of storage periods and edible covers on total acidity of Valencia orange fruit

As it can be distinguish from Fig. 10, pH value was decreased during storage periods from 3.64 to 3.06 at the beginning to the ninth week of the storage period and then the pH was increased gradually (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Effect of storage periods and edible covers on the pH of Valencia orange fruit

Del caro et al. (2004) investigated Flavonoids changes between different citrus familly during storage and found that in shamouti orange, ascorbic acid increased but Hesperidin reduced by increase storage time. In the work of Del caro et al. (2004) low temperature during storage caused severe biochemical activity in Flavonoids that was in agreement with the result of this study. However, Klimezak and Malecka (2006) reported that little changes in flavanol value show high durability of this component. Further the possible reason behind durability of this bioactive component such as Flavonoids in citrus fruit goes back to geographical zone, weather condition, variety, growth season, harvest time and other conditions (Patil et al. 2004). During storage hesperidin increased initially, and then showed a trend of reduction process. The initial increase in hesperidin may be related to stability and activity of the manonyl transferase. Possibly reduction trend is due to ceasing activity of the manonyl transferase responsible for biosynthesis of hesperidin (Samir et al. 1999). This result is in with agreement of Rapisarda et al. (2008), that low temperature, stimulate flavan biosynthesis in all. Totally, flavan value reduced during storage in novel orange. Next reduction in Hesperidin may be due to lack of primary substrate for synthesis of this component (Harborne 1967). Further explanation, Flavonoids biosynthesis in citrus is similar with other plants in glycoside form. With regard to Table 3, there is positive correlation between hesperidin and naringin with Antioxidant activity, this result showed that hesperidin and naringin have similar structure, solution type that use for extraction (Aston, water, methanol) and extraction temperature effect on antioxidant activity (Patil et al. 2004). A liner relationship between antioxidant activity with DPPH method and polyphenol concentration in fruits and vegetable has been reported (Robards et al. 2003). There was not any decay and destruction in two cover including clove oil and mixture of wax-clove oil. It may be due to clove oil properties and its effect on hesperidin and naringin in orange skin, because citrus flavonoids come from phenylbenzo-c- pyrone component as secondary metabolites and have antioxidant activity (Marchand 2002). These component could be important for fruits and protect them against stressful condition (Treutter 2006) the results of other studies has been showed that Flavonoid cause to resistance against fungual agents such as penicillium digitatum (green mold). In citrus Green mold is the most important post-harvest disease in citrus fruit. That increase decay and reduce market ability. Ahmadi et al. (2008) reported that flavonoids including hesperidin and naringin have biological, antibacterial and antimicrobial effect.

Table 3.

Correlation among flavonoids and quality attributes of Valencia orange as a function of storage time and coating type

| Studied properties | Hesperidin (ppm) | Naringin (ppm) | TSS (%) | Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | DPPH (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesperidin (ppm) | 1 | ||||

| Naringin (ppm) | 0.632a | 1 | |||

| TSS (%) | −0.003ns | −0.133ns | 1 | ||

| Vitamin C (mg/100 g) | 0.166ns | −0.129ns | 0.356a | 1 | |

| DPPH (%) | 0.307a | 0.442a | −0.356a | 0.072ns | 1 |

ns not significant

aSignificant at 1 % level

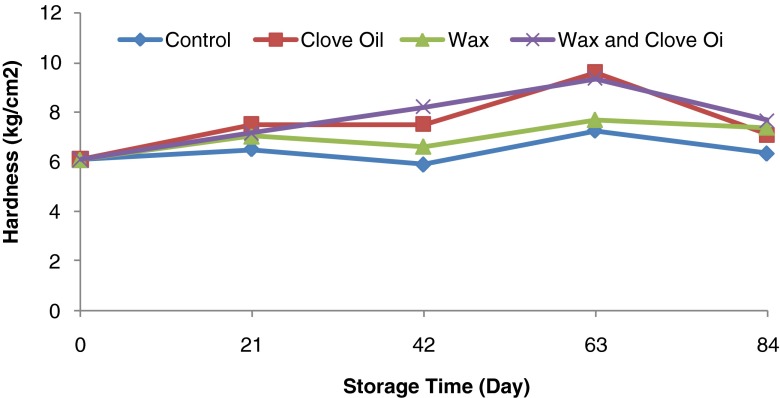

According to the analysis of variance (Table 1) the effect of the storage period, type of cover and their interaction effect on the fruit hardness were significant (p < 0.05). According to Fig. 11 fruit hardness increased during the storage period from 6.1 kg/cm2 (at the beginning of storage period) to its greatest amount (193.42 kg/cm2) on the ninth week of storage and then showed a lower decrease to 7.1 kg/cm2.

Fig. 11.

Effect of storage periods and edible covers on fruit hardness of Valencia orange fruit during storage

Result showed that there was a significant difference between different treatments in respect to fruit hardness and the highest and lowest amount of fruit hardness (8.1 and 6.4 kg/cm2) were related to the wax-oil treatment and control samples respectively (p < 0.05).

Edible coating can be act as barrier agent and prevent water loss from fruits surface and so decrease cell wall decomposition and maintain fruit hardness during storage periods which similar to results of other researchers on the application of Chitosan to Strawberry fruit (Del-Valle et al. 2005).

Variation in carbohydrates content during storage period

According to the analysis of variance (Table 2), storage period and its interaction with edible cover had significant effect on total sugar, glucose, fructose and sucrose during storage period but only glucose affected significantly by the type of edible covers (p < 0.05).

Table 2.

ANOVA of carbohydrates measurement of Valencia orange as a function of storage time and coating type

| Surce of variation | df | Total sugar | Glucose | Fructose | Sucrose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of cover | 3 | 32.156ns | 29.030a | 26.948ns | 34.977ns |

| Time | 4 | 2040.247b | 7150.321b | 68.96b | 3488.048b |

| Type of cover × time | 9 | 85.902a | 62.140b | 2.88a | 103.032b |

Superscripts ns, a and b means not significant, significant at 0.05 and 0.01 level respectively

As can be noticed from the Fig. 12, the amount of total sugar increased from 40.27 to 68.61 (mg/100 g fruit tissue) at the beginning to the ninth week of the storage period. But at the end of the storage period the amount of total sugar was reduced so that its amount on the last day of storage was 53.63 (mg/100 g fruit tissue).

Fig. 12.

Effect of storage periods and edible covers on total sugar of Valencia orange fruit

As can be distinguish from the Fig. 13, the amount of glucose decreased from 68.48 to 18.4 (mg/100 g fruit tissue) at the beginning to the end of the storage period. The highest amount of glucose content was related to control samples (46.16 mg/100 g fruit tissue) and coated samples with wax (43.27 mg/100 g fruit tissue) and coated samples with mixture of wax-clove oil (40.99 mg/100 g fruit tissue) had the lower amount of glucose content.

Fig. 13.

Effect of storage periods and edible covers on glucose content of Valencia orange fruit

According to the Fig. 14, the amount of fructose increased from 28.25 to 51.49 (mg/100 g fruit tissue) at the beginning to the sixth week of the storage period and then its trend decreased till 35.33 (mg/100 g fruit tissue). It must be mentioned that trend of fructose variation was increasingly in the whole process of storage.

Fig. 14.

Effect of storage periods and edible covers on fructose content of Valencia orange fruit

The trend of sucrose change was different with other measured sugars variation (Fig. 15). Sucrose at first showed a reduction in trend and reduced from 55.25 (mg/100 g of fruit) to the lowest amount (31.68 mg/100 g of fruit). At the beginning to sixth week, but its trend increased to the highest amount 68.20 (mg/100 g fruit tissue) while at the ninth week of storage reduced to 54.51 (mg/100 g fruit tissue) at the end of storage period.

Fig. 15.

Variation in sucrose content of Valencia orange during storage

In this study, the amount of total sugar was increased during storage which can be due to the reduction of the water inside the fruit and organic acid decomposion that used as a source of energy. previous studies has shown that the synthesis of organic acid from glucose is a mechanism for continuous increase in sugar level in citrus fruits, but the presence and increase of glicolitik enzymes during storage can lead to different behavior (Echeverria and Valich 1989).

As can be seen from the result of carbohydrates measurement in the end of the storage period, coated samples with mixture of waxes-essential oils due to anaerobic conditions that creates by this type of cover, had the lowest amount of carbohydrates. In other words this cover reduces gas exchange and developed anaerobic conditions in fruits and that resulted in reduction of oxygen and increased CO2 within the fruit and produce ethanol in fruit (Porat et al. 2005(. Result of other studies revealed that at the end of storage period, the amount of sugar content in coated orange was lower than uncoated ones. This may be due to sugar conversion to ethanol under anaerobic conditions that caused by the waxes (Obeland et al. 2008). Results of correlation study were showed in Table 4. As can be seen from Table 4, relation between glucose content with sucrose and total sugar content were negative (p < 0.05) while fructose content had negative correlation with sucrose content and its correlation with total sugar is positive and significant (p < 0.01). Correlation between sucrose and total sugars was positive and significant (p < 0.01). This result is in agreement with the trend of different carbohydrate variation during storage periods.

Table 4.

Correlation among different sugars content in Valencia orange as a function of storage time and coating type

| Studied properties | Glucose content (mg/100 g) | Fructose content (mg/100 g) | Sucrose content (mg/100 g) | Total sugars (mg/100 g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose content (mg/100 g) | 1 | 0.0556ns | −0.505a | −0.379a |

| Fructose content (mg/100 g) | 0.0556ns | 1 | −0.214b | 0.704a |

| Sucrose content (mg/100 g) | −0.505a | −0.214b | 1 | 0.267b |

| Total sugars (mg/100 g) | −0.379a | 0.704a | 0.267b | 1 |

ns not significant

aSignificant at 1 % level

bSignificant at 5 % level

Conclusions

Mixture application of wax and clove oil had significant impact on antioxidant activity. The coating treatment of clove oil had the highest significant effect on preservation of hesperidin during storage while naringin indicated a decreasing trend during storage. Vitamin C content had an increasing trend until 42 days after storage, then a decreasing trend widespread. Coating materials could not alter the content of vitamin C and naringin during storage. The coating treatments of clove oil and mixture of wax and clove oil significantly prevent fruit decay during storage.

Contributor Information

M. Sharifani, Email: mmsharif2@gmail.com

A. Daraei Garmakhany, Phone: +98-9369111454, Email: amirdaraey@yahoo.com

References

- Ahmad M, Khalid ZM, Farooqi WA. Effect of waxing and lining material on storage life of some citrus fruits. Hortic Soc. 1997;92:237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi A, Hosseinimehr SJ, Naghshvar F, Hajir E. Chemoprotective effects of hesperidin against genotoxicity induced by cyclophosphamide in mice bone marrow cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2008;31:794–797. doi: 10.1007/s12272-001-1228-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque B, Lidon FC, Barreiro MG. A case study of tendral winter melons Cucumis melo L. postharest senescence. Gen Appl Plant Physiol. 2005;31:157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WG, McKinley RS, Colavecchia M. The use of clove oil as an anaesthetic for rainbow trout and its effects on swimming performance. North Am J Fish Manag. 1997;17:301–307. doi: 10.1577/1548-8675(1997)017<0301:TUOCOA>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis. 18. Washington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ashwell G. Colorimetric analysis of saccharides. In: Colowick SP, Kaplan NO, editors. Methods in enzymology, vol. 3. New York: Academic Press Inc; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;26:1199–1200. doi: 10.1038/1811199a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Briozzo JL, Chirife J, Herzage L, D’Aquino M. Antimicrobial activity of clove oil dispersed in a concentrated sugar solution. J Appl Bacteriol. 1989;66:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb02456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Caro A, Piga A, Vacca V, Agabbio M. Changes of fl avonoids, vitamin C and antioxidant capacity in minimally processed citrus segments and juices during storage. Food Chem. 2004;84:99–105. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(03)00180-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Del-Valle V, Hernandez-Munoz P, Guarda A, Galotto MJ. Development of a cactus-musilage edible coating (opuntia Ficus indica) and its application to extend strawberry (Fragaria ananassa) shelf-life. Food Chem. 2005;91:751–756. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria E, Valich J. Enzymes of sugar and acid metabolism in stored Valencia oranges. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1989;114:445–449. [Google Scholar]

- Escarpa A, Gonzahez MC. Approach to the content of total extractable phenolic compounds from different food samples by comparison of chromatographic and spectrophotometric methods. Anal Chim Acta. 2001;427:119–127. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(00)01188-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evensen KB. Effects of maturities at harvest, storage temperature and cultivar on muskmelon quality. Hort Sci. 1983;18:907–913. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Shiura T, Masuda M, Tokunaga M, Kawase A, Iwaki M, et al. Anti-allergic effect of a combination of Citrus unshiu unripe fruits extract and prednisolone on picryl chloride induced contact dermatitis in mice. J Nat Med. 2008;62:202–206. doi: 10.1007/s11418-007-0208-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galati EM, Monforte MT, Kirjavainen S, Forestieri AM, Trovato A. Biological effects of hesperidin, a citrus flavonoid. (Note I): antiinflamatory and analgesic activity. Farmaco. 1994;49:709–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner PT, White AC, McPhail DB, Duthie GG. The relative contributions of vitamin C, carotenoids and phenolic to the antioxidant potential of fruit juices. Food Chem. 2000;68:471–474. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(99)00225-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Izquierdo A, Gil MI, Ferreres F, Tomas-Barberan F. In vitro availability of flavanoids and other phenolics in orange juice. J Agrci Food Chem. 2001;49:1035–1041. doi: 10.1021/jf0000528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handel EV. Direct microdetermination of sucrose. Anal Biochem. 1968;22:280–283. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90317-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harborne JB. Comparatative biochemistry of the flavonoids. London: Academic; 1967. pp. 270–275. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz RM, Gentili B. Flavonoid constituents of Citrus. In: Nagy S, Shaw PE, Veldhuis MK, editors. Citrus science and technology, vol. 1. Westport: Avi Publishing; 1977. pp. 397–426. [Google Scholar]

- Kays SJ (1997) Post harvest physiology of perishable plant products. Vas Nostrand Rein Hold Book. AVI Publish. Co., pp. 147–316

- Klimezak I, Malecka M. Effect of storage on the content of polyphenols, vitamin C and the antioxidant activity of orange juices. J Food Compos Anal. 2006;20:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2006.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroyer G. Uber die antioxidative aktivitat von zitrusfruchtschalen (antioxidant activity of citrus peels) Z Ernaehrungswiss. 1986;25:63–69. doi: 10.1007/BF02023620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar J, Sharma RK, Singh R. The effect of different methods of packing on the shelf life of kinnow. J Hort Sci. 2000;29:202–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Coates GA. Vitamin C in frozen, fresh squeezed, unpasteurized, polyethylene-bottled orange juice: A storage study. Food Chem. 1999;65:165–168. doi: 10.1016/S0308-8146(98)00180-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SK, Kader AA. Preharvest nd postharvest factors influencing vitamin C content of horticultural crops. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2000;20:207–220. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00133-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim YY, Lim TT, Tee JJ (2006) Antioxidnat properties of Guava fruit; comparison with some local fruit. Suway Acad J (3):9–20

- Manzano JE, Diaz A. Effect of storage time, temperature and wax coating on the quality of fruits of ‘Valencia’ orange (Citrus sinensis L.) Proc Int Soc Trop Hort. 2001;44:24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand LL. Cancer preventive effects of flavonoids—a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2002;56:296–301. doi: 10.1016/S0753-3322(02)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCready RM, Guggolz J, Silviera V, Owens HS. Determination of srarch and amylase in vegetables. Anal Chem. 1950;22:1156–1158. doi: 10.1021/ac60045a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GL. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal Chem. 1959;31:426–428. doi: 10.1021/ac60147a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monforte MT, Trovato A, Kirjavainen S, Forestieri AM, Galati EM. Biological effects of hesperidin, a citrus flavonoid. (Note II): hypolipidemic activity in on experimental hyper cholesteroremia in rat. Farmaco. 1995;50:595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mylonasa CC, Cardinalettia TG, Sigelakia I, Polzonetti-Magni A. Comparative efficacy of clove oil and 2-phenoxyethanol as anesthetics in the aquaculture of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax) and gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) at different temperatures. Aquaculture. 2005;246:467–481. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.02.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obeland D, Collins S, Sievert J, Fjeld K, Doctor J, Arpaia ML. Comercial packing and storage of Naval oranges alter aroma volatile and reduces flavor quality. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2008;47:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2007.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Omokolo N, Tasala D, Djogoue FP. Change in carbohydrate, amino acid and phenol content in cocoa pods from three clones after infection with phytophtora megakary a Bra and Grif. Ann Bot. 1996;77:153–158. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1996.0017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paolo R, Marisol LB. Effect of cold storage on vitamin C, phenolics and antioxidant activity of five orange genotypes (Citrus sinensis (L.)Osbeck) Postharvest Biol Technol. 2008;49:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil BS, Vanamala J, Hallman G. Irradiation and storage influence on bioactive components and quality of early and late season “Rio Red” grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macf.) Postharvest Biol Technol. 2004;34:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2004.03.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson J, Dwyer J. Flavonoids: dietary occurrence and biochemical activity. Nutr Res. 1998;18:1995–2018. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(98)00169-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porat R, Weiss B, Cohen L, Daus A, Biton A. Effects of polyethylene wax content and composition on taste, quality, and emission of off-flavor volatiles in Mor mandarin. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2005;38:262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2005.07.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapisarda P, Lo Bianco M, Pannuzzo P, Timpanaro N. Effect of cold storage on vitamin C, phenolics and antioxidant activity of five orange genotypes [Citrus sinensis L) Postharvest Biol Technol. 2008;49:348–354. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2008.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robards K, Li X, Antolovich M, Boyd S. Characterization of citrus by chromatographic analysis of flavonoids. J Sci Food Agric. 2003;75:87–101. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199709)75:1<87::AID-JSFA846>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samir A, David S, Zhao K, Ross S, Ziska D, Elsohly M. Variance of common flavonoids by brand of grapefruit juice. Fitoteropia. 1999;71:157–167. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(99)00131-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentandreu E, Izquierdo L, Sendra JM. Differentiation of juices from clementine (Citrus clementina), clementine-hybrids and satsuma (Citrus unshiu) cultivars by statistical multivariate discriminant analysis of their flavanone-7- O-glycosides and fully methoxylated flavones content as determined by liquid chromatography. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2007;224:421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Shahid MN, Abbasi NA. Effect of bee wax coatings on physiological changes in fruits of sweet orange CV. “blood red” Sarhad. J Agric. 2011;27:385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Shin DB, Lee D-W, Yang R, Kim J-A. Antioxidative properties and flavonoids contents of matured citrus peel extracts. Food Sci Biotechnol. 2006;15:356–357. [Google Scholar]

- Slinkard K, Singleton VL. Total phenol analysis; automation and comparison with manual methods. Am J Enol Vitic. 1977;28:49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari AK. Imbalance in antioxidant defense and human diseases: multiple approach of natural antioxidants therapy. Curr Sci. 2001;81:1179–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Treutter D. Significance of flavonoids in plant resistance: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2006;4:147–157. doi: 10.1007/s10311-006-0068-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verma P, Dashora LK. Post-harvest physiconutritional changes in Kagzi Limes (Citrus aurantifolia Swingle) treated with selected oil emulsions and diphenyl. Plant Food Hum Nut. 2000;55:279–284. doi: 10.1023/A:1008140820846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo KM, Hwang IK, Park JH, Moon B. Major phytochemical composition of 3 native Korean citrus varieties and bioactive activity on V79-4 cells induced by oxidative stress. J Food Sci. 2009;74:C462–C468. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousof S, Gasal H, King G. Naringin content in lical fruit. Food chem. 1999;37:113–121. doi: 10.1016/0308-8146(90)90085-I. [DOI] [Google Scholar]